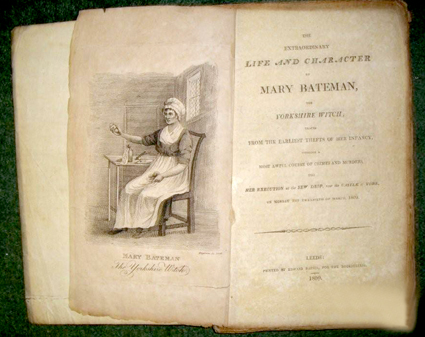

Mary Bateman was born of

reputable parents at Aisenby in the North Riding of Yorkshire, in the

year 1768: her father, whose name was Harker, carrying on business as

a small farmer. As early as at the age of five years, she exhibited

much of that sly knavery, which subsequently so extraordinarily

distinguished her character; and many were the frauds and falsehoods,

of which she was guilty, and for which she was punished. In the year

1780, she first quitted her father's house, to undertake the duties of

a servant in Thirsk, but having been guilty of some peccadilloes, she

proceeded to York in 1787.

Before she had been in that city

more than twelve months, she was detected in pilfering some trifling

articles of property belonging to her mistress, and was compelled to

run off to Leeds, without waiting either for her wages or her clothes.

For a considerable time she remained without employment or friends,

but at length, upon the recommendation of an acquaintance of her

mother, she obtained an engagement in the shop of a mantua maker, in

whose service she remained for more than three years. She then became

acquainted with John Bateman, to whom after three weeks' courtship she

was married in the year 1792.

Within two months after her

marriage, she was found to have been guilty of many frauds, and she

only escaped prosecution by inducing her husband to move frequently

from place to place, so as to escape apprehension; and at length poor

Bateman, driven almost wild by the tricks of his wife, entered the

supplementary militia. Mrs Bateman was now entirely thrown upon her

own resources and, unable to follow any reputable trade, she in the

year 1799 took up her residence in Marsh Lane, near Timble Bridge,

Leeds, and proceeded to deal in fortune-telling and the sale of

charms.

From a long course of iniquity,

carried on chiefly through the medium of the most wily arts, she had

acquired a manner and a mode of speech peculiarly adapted to her new

profession, and abundance of credulous victims daily presented

themselves to her. It would be useless to follow this wretched woman

through the subsequent scenes of her miserable life. Fraud and deceit

were the only means by which she was able to carry on the war, and

numerous were the impudent and heartless schemes which she put into

operation to dupe the unhappy objects of her at tacks. Her character

was such as to prevent her long pursuing her occupation in one

position, and she was repeatedly compelled to change her abode until

she at length took up her residence in Black Dog Lane, where she was

apprehended.

Her husband at this time had

returned from the militia several years, and although he followed the

trade to which he had been brought up, there can be little doubt that

he shared the proceeds of his wife's villainies. She was indicted at

York on the 18th of March 1809, for the wilful murder of Rebecca

Perigo of Bramley in the same county, in the month of May in the

previous year.

The examination of the

witnesses, who were called to support the case for the prosecution,

showed, that Mrs Bateman resided at Leeds, and was well known at that

place, as well as in the surrounding districts, as a 'witch', in which

capacity she had been frequently employed to work cures of 'evil

wishes', and all the other customary imaginary illnesses, to which the

credulous lower orders at that time supposed themselves liable. Her

name had become much celebrated in the neighbourhood for her successes

in the arts of divining and witchcraft, and it may be readily

concluded that her efforts in her own behalf were no less profitable.

In the spring of 1806 Mrs

Perigo, who lived with her husband at Bramley, a village at a short

distance from Leeds, was seized with a 'flacking', or fluttering in

her breast whenever she lay down, and applying to a quack doctor of

the place, he assured her that it was beyond his cure, for that an

'evil wish' had been laid upon her, and that the arts of sorcery must

be resorted to in order to effect her relief.

While in this dilemma, she was

visited by her niece, a girl named Stead, who at that time filled a

situation as a household servant at Leeds, and who had taken advantage

of the Whitsuntide holidays to go round to see her friends. Stead

expressed her sorrow to find her aunt in so terrible a situation, and

recommended an immediate appeal to the prisoner, whose powers she

described as fully equal to get rid of any affection of the kind,

whether produced by mortal or diabolical charms.

An application was at once

determined on, and Stead was employed to broach the subject to the

diviner. She, in consequence, paid the prisoner a visit at her house

in Black Dog Yard, near the bank at Leeds. Having acquainted her with

the nature of the malady by which her aunt was affected, she was

informed that the prisoner knew a lady who lived at Scarborough, and

that if a flannel petticoat or some article of dress, which was worn

next the skin of the patient, was sent to her, she would at once

communicate with this lady upon the subject.

On the following Tuesday,

William Perigo, the husband of the deceased, proceeded to her house,

and having handed over his wife's flannel petticoat, the prisoner said

that she would write to Miss Blythe, who was the lady to whom she had

alluded at Scarborough, by the same night's post, and that an answer

would doubtless be returned by that day week, when he was to call

again.

On the day mentioned, Perigo was

true to his appointment, and the prisoner produced to him a letter,

saying that it had arrived from Miss Blythe, and that it contained

directions as to what was to be done. After a great deal of

circumlocution and mystery the letter was opened and read by the

prisoner, and it was found that it contained an order 'that Mary

Bateman should go to Perigo's house at Bramley, and should take with

her four guinea notes, which were enclosed, and that she should sew

them into the four corners of the bed, in which the diseased woman

slept.'

There they were to remain for eighteen months.

Perigo was to give her four other notes of like

value, to be returned to Scarborough. Unless all these directions were

strictly attended to, the charm would be useless and would not work.

On the 4th of August the

prisoner went over to Bramley, and having shown the four notes,

proceeded apparently to sew them up in silken bags, which she

delivered over to Mrs Perigo to be placed in the bed. The four notes

desired to be returned were then handed to her by Perigo and she

retired, directing her dupes frequently to send to her house, as

letters might be expected from Miss Blythe.

In about a fortnight, another

letter was produced, and it contained directions that two pieces of

iron in the form of horse-shoes should be nailed up by the prisoner at

Perigo's door, but that the nails should not be driven in with a

hammer, but with the back of a pair of pincers, and that the pincers

were to be sent to Scarborough, to remain in the custody of Miss

Blythe for the eighteen months already mentioned in the charm. The

prisoner accordingly again visited Bramley and, having nailed up the

horse-shoes, received and carried off the pincers.

In October the following letter

was received by Perigo, bearing the signature of the supposed Miss

Blythe.

'My dear Friend --

You must go down to Mary Bateman's at Leeds, on Tuesday next, and

carry two guinea notes with you and give her them, and she will give

you other two that I have sent to her from Scarborough, and you must

buy me a small cheese about six or eight pound weight, and it must be

of your buying, for it is for a particular use, and it is to be

carried down to Mary Bateman's, and she will send it to me by the

coach -- This letter is to be burned when you have done reading it.'

From this time to the month of

March 1807, a great number of letters were received, demanding the

transmission of various articles to Miss Blythe through the medium of

the prisoner. All these were to be preserved by her until the

expiration of the eighteen months. In the course of the same period

money to the amount of near seventy pounds was paid over, Perigo, upon

each occasion of payment, receiving silk bags, containing what were

pretended to be coins or notes of corresponding value, which were to

be sewn up in the bed as before. In March 1807, the following letter

arrived.

'My dear Friends –

I will be obliged to you if you will let me have half-a-dozen of your

china, three silver spoons, half-a-pound of tea, two pounds of loaf

sugar, and a tea canister to put the tea in, or else it will not do --

I durst not drink out of my own china. You must burn this with a

candle.'

The china, &c, not having been

sent, in the month of April Miss Blythe wrote as follows:

'My dear Friends --

I will be obliged to you if you will buy me a camp bedstead, bed and

bedding, a blanket, a pair of sheets, and a long bolster must come

from your house. You need not buy the best feathers, common ones will

do. I have laid on the floor for three nights, and I cannot lay on my

own bed owing to the planets being so bad concerning your wife, and I

must have one of your buying or it will not do. You must bring down

the china, the sugar, the caddy, the three silver spoons, and the tea

at the same time when you buy the bed, and pack them up altogether. My

brother's boat will be up in a day or two, and I will order my

brother's boatman to call for them all at Mary Bateman's, and you must

give Mary Bateman one shilling for the boatman, and I will place it to

your account. Your wife must burn this as soon as it is read or it

will not do.'

This had the desired effect, and

the prisoner having called upon the Perigos, she accompanied them to

the shops of a Mr Dobbin and a Mr Musgrave at Leeds, to purchase the

various articles named. These were eventually bought at a cost of

sixteen pounds, and sent to Mr Sutton's, at the Lion and Lamb Inn,

Kirkgate, there to await the arrival of the supposed messenger.

At the end of April, the

following letter arrived:

'My dear Friends --

I am sorry to tell you you will take an illness in the month of May

next, one or both of you, but I think both, but the works of God must

have its course. You will escape the chambers of the grave; though you

seem to be dead, yet you will live. Your wife must take half-a-pound

of honey down from Bramley to Mary Bateman's at Leeds, and it must

remain there till you go down yourself, and she will put in such like

stuff as I have sent from Scarbro' to her, and she will put it in when

you come down, and see her yourself, or it will not do. You must eat

pudding for six days, and you must put in such like stuff as I have

sent to Mary Bateman from Scarbro', and she will give your wife it,

but you must not begin to eat of this pudding while I let you know. If

ever you find yourself sickly at any time, you must take each of you a

teaspoonful of this honey; I will remit twenty pounds to you on the

20th day of May, and it will pay a little of what you owe. You must

bring this down to Mary Bateman's, and burn it at her house, when you

come down next time.' The instructions contained in this letter were

complied with, and the prisoner having first mixed a white powder in

the honey, handed over six others of the same colour and description

to Mrs Perigo, saying that they must be used in the precise manner

mentioned upon them, or they would all be killed. On the 5th of May,

another letter arrived in the following terms:

'My dear Friends --

You must begin to eat pudding on the 11th of May, and you must put one

of the powders in every day as they are marked, for six days -- and

you must see it put in yourself every day or else it will not do. If

you find yourself sickly at any time you must not have no doctor, for

it will not do, and you must not let the boy that used to eat with you

eat of that pudding for six days; and you must make only just as much

as you can eat yourselves, if there is any left it will not do. You

must keep the door fast as much as possible or you will be overcome by

some enemy. Now think on and take my directions or else it will kill

us all. About the 25th of May I will come to Leeds and send for your

wife to Mary Bateman's; your wife will take me by the hand and say,

"God bless you that I ever found you out." It has pleased God to send

me into the world that I might destroy the works of darkness; I call

them the works of darkness because they are dark to you -- now mind

what I say whatever you do, This letter must be burned in straw on the

hearth by your wife.'

The absurd credulity of Mr and

Mrs Perigo even yet favoured the horrid designs of the prisoner; and,

in obedience to the directions which they received, they began to eat

the puddings on the day named. For five days they had no particular

flavour, but upon the sixth powder being mixed, the pudding was found

so nauseous that the former could only eat one or two mouthfuls, while

his wife managed to swallow three or four. They were both directly

seized with violent vomiting and Mrs Perigo, whose faith appears to

have been greater than that of her husband, at once had recourse to

the honey.

Their sickness continued during

the whole day, but although Mrs Perigo suffered the most intense

torments, she positively refused to hear of a doctor's being sent for,

lest, as she said, the charm should be broken by Miss Blythe's

directions being opposed. The recovery of the husband, from the

illness by which he was affected, slowly progressed; but the wife, who

persisted in eating the honey, continued daily to lose strength. She

at length expired on the 24th of May, her last words being a request

to her husband not to be 'rash' with Mary Bateman, but to await the

coming of the appointed time. Mr Chorley, a surgeon, was

subsequently called in to see her body, but although he expressed his

firm belief that the death of the deceased was caused by her having

taken poison, and although that impression was confirmed by the

circumstance of a cat dying immediately after it had eaten some of the

pudding, no further steps were taken to ascertain the real cause of

death, and Perigo even subsequently continued in communication with

the prisoner.

Upon his informing her of the

death of his wife, she at once declared that it was attributable to

her having eaten all the honey at once. Then in the beginning of June,

he received the following letter from Miss Blythe:

'My dear Friend

--

I am sorry to tell you that your wife should touch of those things

which I ordered her not, and for that reason it has caused her death;

it had likened to have killed me at Scarborough, and Mary Bateman at

Leeds, and you and all, and for this reason, she will rise from the

grave, she will stroke your face with her right hand, and you will

lose the use of one side, but I will pray for you. I would not have

you to go to no doctor, for it will not do. I would have you to eat

and drink what you like, and you will be better. Now, my dear friend,

take my directions, do and it will be better for you. Pray God bless

you. Amen. Amen. You must burn this letter immediately after it is

read.'

Letters were also subsequently

received by him, purporting to be from the same person, in which new

demands for clothing, coals, and other articles were made, but at

length, in the month of October 1808, two years having elapsed since

the commencement of the charm, he thought that the time had fully

arrived when, if any good effects were to be produced from it, they

would have been apparent, and that therefore he was entitled to look

for his money in the bed. He in consequence commenced a search for the

little silk bags in which his notes and money had been, as he

supposed, sewn up; but although the bags indeed were in precisely the

same positions in which they had been placed by his deceased wife, by

some unaccountable conjuration, the notes and gold had turned to

rotten cabbage-leaves and bad farthings.

The darkness, by which the truth

had been so long obscured, now passed away, and having communicated

with the prisoner, by a stratagem, meeting her under pretence of

receiving from her a bottle of medicine, which was to cure him from

the effects of the puddings which still remained, he caused her to be

apprehended. Upon her house being searched, nearly all the property

sent to the supposed Miss Blythe was found in her possession, and a

bottle containing a liquid mixed with two powders, one of which proved

to be oatmeal, and the other arsenic, was taken from her pocket when

she was taken into custody.

The rest of the evidence against

the prisoner went to show that there was no such person as Miss Blythe

living at Scarborough, and that all the letters which had been

received by Perigo were in her own handwriting, and had been sent by

her to Scarborough to be transmitted back again. An attempt was also

proved to have been made by her to purchase some arsenic, at the shop

of a Mr Clough, in Kirkgate, in the month of April 1807. But the most

important testimony was that of Mr Chorley, the surgeon, who

distinctly proved that he had analysed what remained of the pudding

and of the contents of the honey pot, and that he found them both to

contain a deadly poison, called corrosive sublimate of mercury, and

that the symptoms exhibited by the deceased and her husband were such

as would have arisen from the administration of such a drug.

The prisoner's defence consisted

of a simple denial of the charge, and the learned judge then proceeded

to address the jury. Having stated the nature of the allegations made

in the indictment, he said that in order to come to a conclusion as to

the guilt of the prisoner, it was necessary that three points should

be clearly made out. 1st. That the deceased died of poison. 2nd. That

that poison was administered by the contrivance and knowledge of the

prisoner. 3rd. That it was so done for the purpose of occasioning the

death of the deceased.

A large body of evidence had

been laid before them, to prove that the prisoner had engaged in

schemes of fraud against the deceased and her husband, which was

proved not merely by the evidence of Wm. Perigo, but by the testimony

of other witnesses. The inference the prosecutors drew from this fraud

was the existence of a powerful motive or temptation to commit a still

greater crime, for the purpose of escaping the shame and punishment

which must have attended the detection of the fraud -- a fraud so

gross, that it excited his surprise that any individual in that age

and nation could be the dupe of it. But the jury should not go beyond

this inference, and presume that, because the prisoner had been guilty

of fraud, she was of course likely to have committed the crime of

murder.

That, if proved, must be shown

by other evidence. His Lordship then proceeded to recapitulate the

whole of the evidence, as detailed in the preceding pages, and

concluded with the following observations. 'It is impossible not to be

struck with wonder at the extraordinary credulity of Wm. Perigo, which

neither the loss of his property, the death of his wife nor his own

severe sufferings, could dispel. It was not until the month of October

in the following year, that he ventured to open his his treasure, and

found there what everyone in court must have anticipated, that he

would find not a single vestige of his property.

His evidence is laid before the

jury with the observation which arises from this uncommon want of

judgement, but his memory appears to be very retentive and his

evidence is confirmed, and that in different parts of the narrative,

by other witnesses, while many parts of the case do not rest upon his

evidence at all. The illness and peculiar symptoms, which preceded the

death of his wife, his own severe sickness, and a variety of other

circumstances attending the experiments made upon the pudding, were

proved by separate and independent testimony.

It is most strange that, in a

case of so much suspicion as it appeared to have excited at the time,

the interment of the body should have taken place without any inquiry

as to the cause of death, an inquiry which then would have been much

less difficult, though the fact of the deceased having died of poison

is now well established. The main question is, did the prisoner

contrive the means to induce the deceased to take it? If she did so

contrive the means, the intent could only be to destroy. Poison so

deadly could not be administered with any other view.

The jury will lay all the facts

and circumstances together; and if they feel them press so strongly

against the prisoner, as to induce a conviction of the prisoner's

having procured the deceased to take poison with an intent to occasion

her death, they will find her guilty. If they do not think the

evidence conclusive, they will, in that case, find the prisoner not

guilty.'

The jury, after conferring for a

moment, found the prisoner guilty, and the judge proceeded to pass

sentence of death upon her, in nearly the following words:

'Mary Bateman, you have been

convicted of wilful murder by a jury who, after having examined your

case with caution, have, constrained by the force of evidence,

pronounced you guilty. It only remains for me to fulfil my painful

duty by passing upon you the awful sentence of the law. After you have

been so long in the situation in which you now stand, and harassed as

your mind must be by the long detail of your crimes and by listening

to the sufferings you have occasioned, I do not wish to add to your

distress by saying more than my duty renders necessary. Of your guilt,

there cannot remain a particle of doubt in the breast of anyone who

has heard your case. You entered into a long and premeditated system

of fraud, which you carried on for a length of time which is most

astonishing, and by means which one would have supposed could not, in

this age and nation, have been practised with success. To prevent a

discovery of your complicated fraud, and the punishment which must

have resulted therefrom, you deliberately contrived the death of the

persons you had so grossly injured, and that by means of poison, a

mode of destruction against which there is no sure protection. But

your guilty design was not fully accomplished, and, after so

extraordinary a lapse of time, you are reserved as a signal example of

the justice of that mysterious Providence, which, sooner or later,

overtakes guilt like yours. At the very time when you were

apprehended, there is the greatest reason to suppose, that if your

surviving victim had met you alone, as you wished him to do, you would

have administered to him a more deadly dose, which would have

completed the diabolical project you had long before formed, but which

at that time only partially succeeded; for upon your person, at that

moment, was found a phial containing a most deadly poison. For crimes

like yours, in this world, the gates of mercy are closed. You afforded

your victim no time for preparation, but the law, while it dooms you

to death, has, in its mercy, afforded you time for repentance, and the

assistance of pious and devout men, whose admonitions, and prayers,

and counsels may assist to prepare you for another world, where even

your crimes, if sincerely repented of, may find mercy.

'The sentence of the law is, and

the court doth award it, That you be taken to the place from whence

you came, and from thence, on Monday next, to the place of execution,

there to be hanged by the neck until you are dead, and that your body

be given to the surgeons to be dissected and anatomized. And may

Almighty God have mercy upon your soul.'

The prisoner having intimated

that she was pregnant, the clerk of the arraigns said, 'Mary Bateman,

what have you to say, why immediate execution should not be awarded

against you?' On which the prisoner pleaded that she was twenty-two

weeks gone with child. On this plea the judge ordered the sheriff to

empanel a jury of matrons: this order created a general consternation

among the ladies, who hastened to quit the court, to prevent the

execution of so painful an office being imposed upon them. His

lordship, in consequence, ordered the doors to be closed, and in about

half-an-hour, twelve married women being empanelled, they were sworn

in court, and charged to inquire 'whether the prisoner was with quick

child?' The jury of matrons then retired with the prisoner, and on

their return into court delivered their verdict, which was that Mary

Bateman is not with quick child. The execution of course was not

respited, and she was remanded back to prison.

During the brief interval

between her receiving sentence of death and her execution, the

ordinary, the Rev George Brown, took great pains to prevail upon her

ingenuously to acknowledge and confess her crimes. Though the prisoner

behaved with decorum during the few hours that remained of her

existence, and readily joined in the customary offices of devotion, no

traits of that deep compunction of mind which, for crimes like hers,

must be felt where repentance is sincere, could be observed; but she

maintained her caution and mystery to the last. On the day preceding

her execution, she wrote a letter to her husband, in which she

enclosed her wedding-ring, with a request that it might be given to

her daughter. She admitted that she had been guilty of many frauds,

but still denied that she had had any intention to produce the death

of Mr or Mrs Perigo.

Upon the Monday morning at five

o'clock she was called from her cell, to undergo the last sentence of

the law. She received the communion with some other prisoners, who

were about to be executed on the same day, but all attempts to induce

her to acknowledge the justice of her sentence, or the crime of which

she had been found guilty, proved vain. She maintained the greatest

firmness in her demeanour to the last, which was in no wise

interrupted even upon her taking leave of her infant child, which lay

sleeping in her cell.

Upon the appearance of the

convict upon the platform, the deepest silence prevailed amongst the

immense assemblage of persons which had been collected to witness the

execution. As final duty, the Rev Mr Brown, immediately before the

drop fell again exhorted the unhappy woman to confession, but her only

reply was a repetition of the declaration of her innocence, and the

next moment terminated her existence.