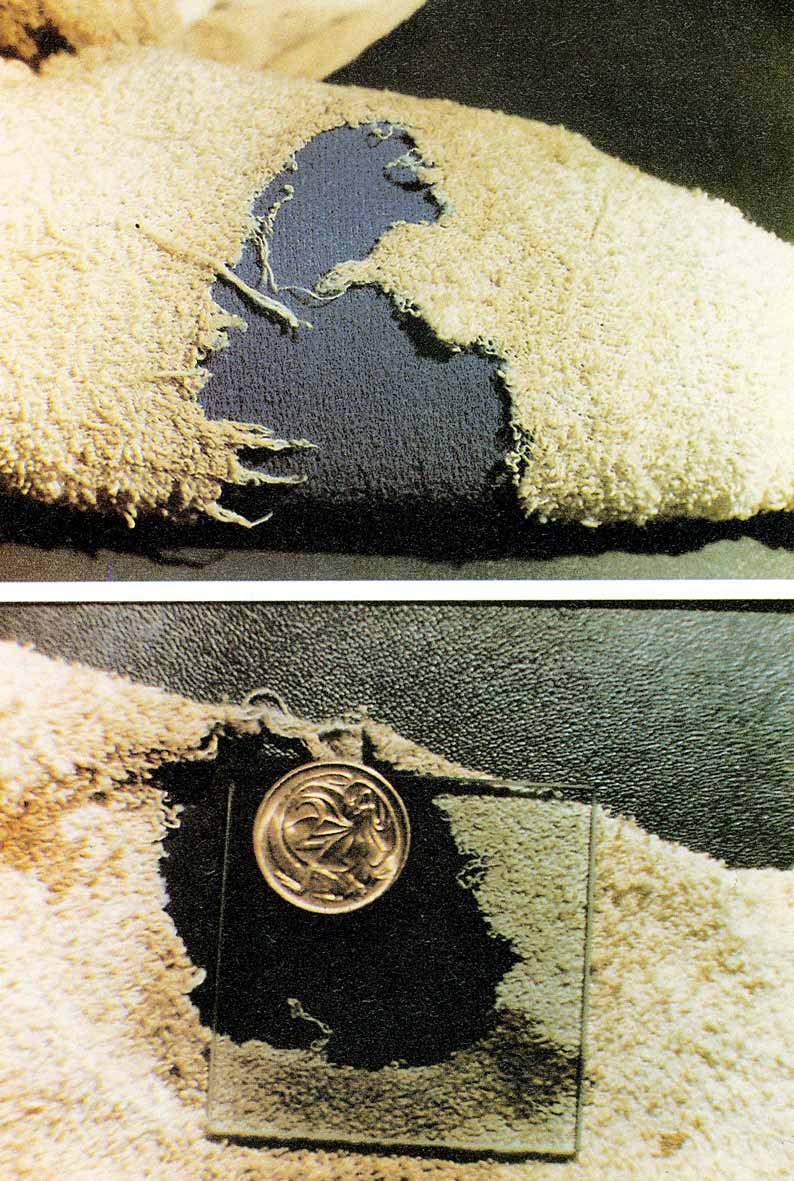

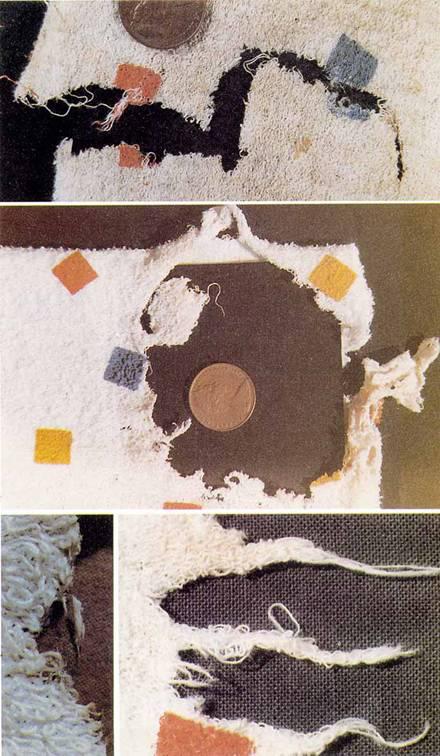

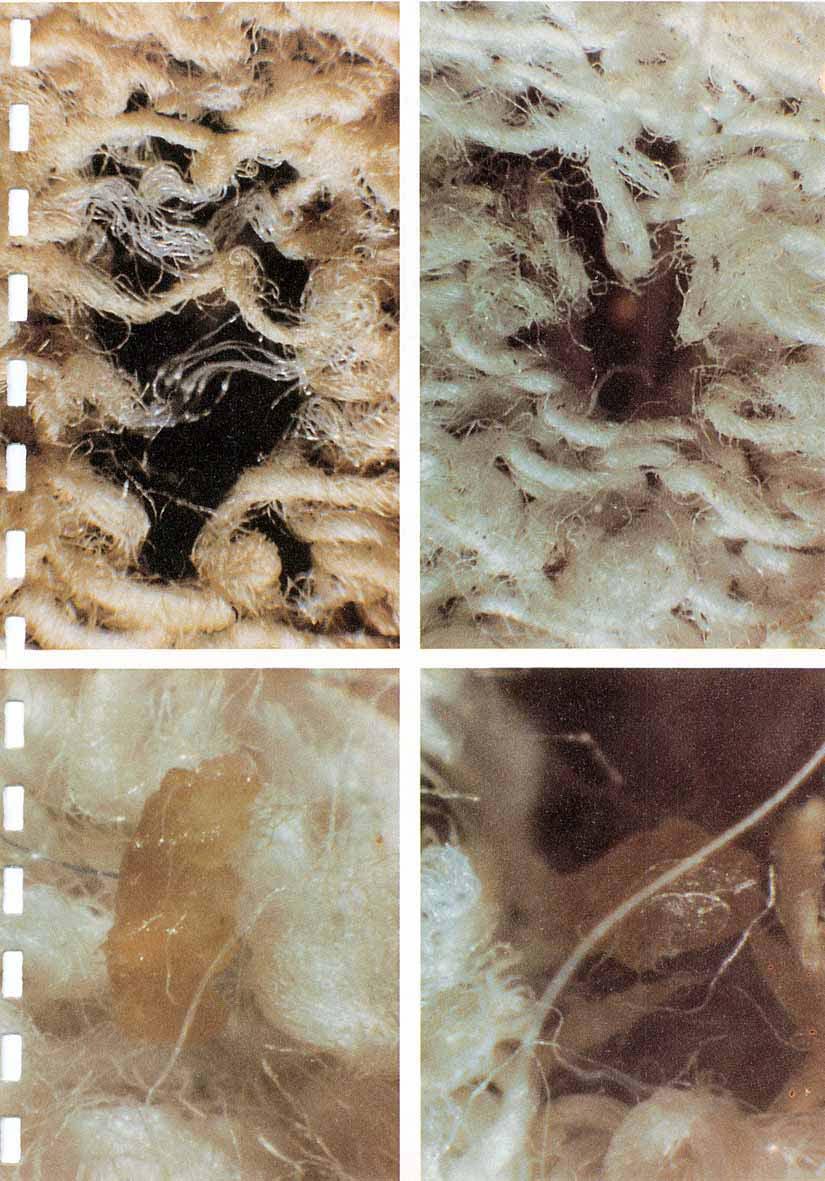

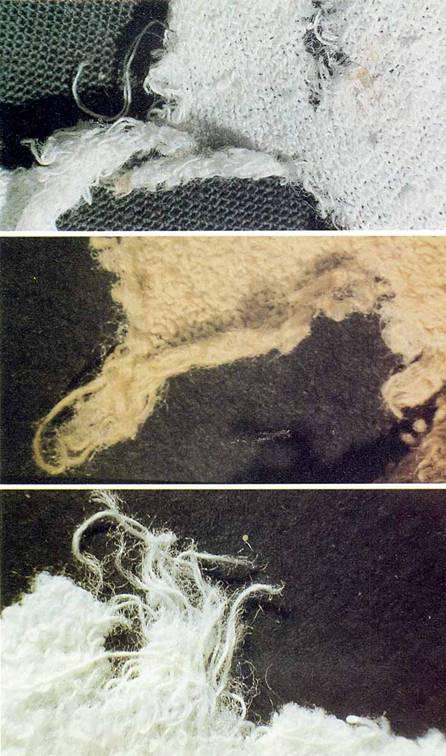

Photograph 1. (top) A partial view of the damaged left sleeve in A

Chamberlain’s jumpsuit. At the top,

centre left and centre right, note the arcs of damage which are

comparable in size and shape to the

canine central incisor damage shown in Photograph 13.

Photograph 2. A partial view of the damaged sleeve of A

Chamberlain’s jumpsuit. The circumference of

the damage seen here is about 100mm. It is formed from about 10 small

cuts joined end to end.

These small cuts range in length from about 8mm up to 15mm. Compare

the size and appearance

of these cuts with known canine cuts, shown in Photograph 12.

Photograph 3. (top) The V cut in the collar of the Chamberlain

jumpsuit. The length and appearance

of these cuts led the Crown to argue that this damage could only have

been caused by scissors.

However further evidence now shows that such damage is entirely

consistent with canine action.

The stretched nylon thread, at the angle of the V is attached on both

sides of the cut.

This is inconsistent with the action of scissors.

Photograph 4. (centre) The cut in the collar of A Chamberlain’s

jumpsuit adjacent to the press stud.

The semi—detached tufts, stretched nylon threads and appearance of the

severed thread ends

are all typical of canine action.

Photograph 5. (bottom) An enlarged view of damage from A

Chamberlain’s jumpsuit, also shown in

Photograph 1, lower left. The appearance of this damage, which shows a

striking resemblance to

known canine damage, should be compared with the canine damage shown

in Photograph 15.

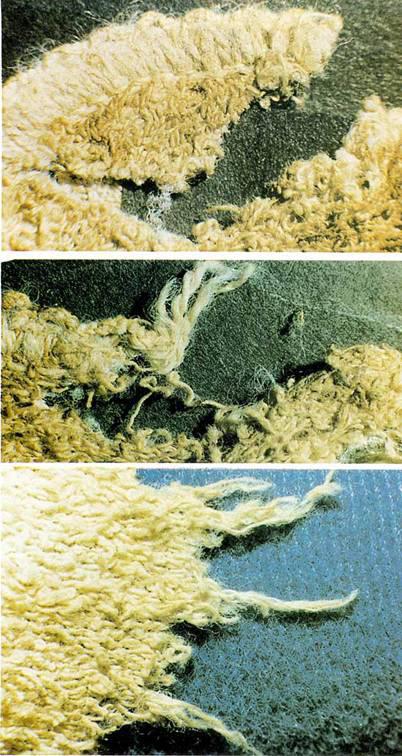

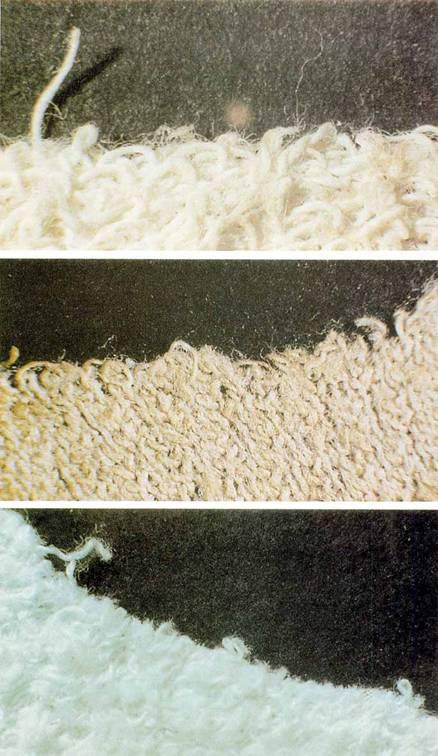

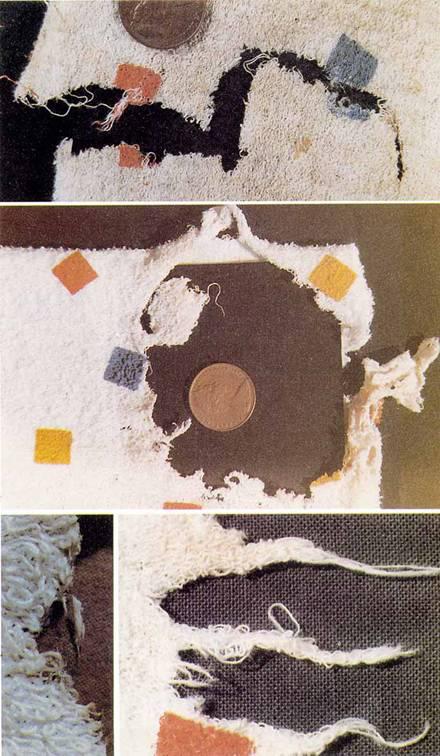

Photograph 6 (top) and Photograph 7. (centre) Scissor cuts in the

arm of a test jumpsuit.

These were produced in the courtroom by Sgt Cocks, to demonstrate how

the Crown

believed the damage in the Chamberlain jumpsuit had been caused.

Photograph 8. (bottom) The cut shown here in the collar of a test

jumpsuit, was produced in

the courtroom by Sgt Cocks to demonstrate how the Crown believed the

collar cut in the

Chamberlain jumpsuit had been made.

"The two constituent cusps [teeth] do not form straight lines but

are arranged so that each

blade has the shape of a wide open V. This increases efficiency by

preventing the meat

from slipping out forwards, and makes the action really more

comparable with that of

pruning shears than of ordinary scissors.’

Photograph 10. A cotton tuft, produced when the pile in Bonds

towelling fabric is cut with a

sharp instrument. At the trial the court was told that the presence of

these tufts constituted

the strongest possible evidence that A Chamberlain’s jumpsuit had been

cut with scissors.

It was not possible — the court was told — for dingo teeth to produce

tufts such as these.

The tufts shown in this photograph were produced by the action of

canine teeth.

Photograph 11. (bottom) The appearance of a group of threads seen

in a sample of canine

damaged fabric illustrates the cutting ability of canine teeth.

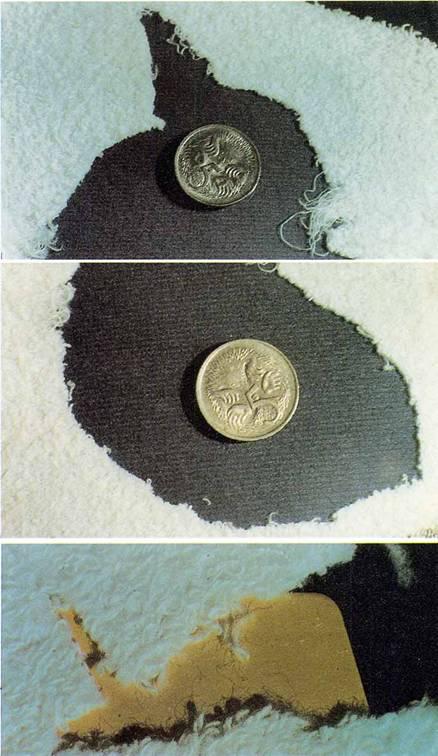

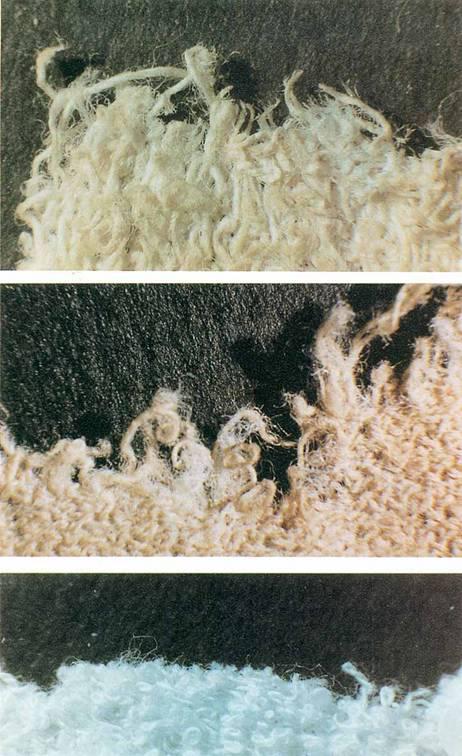

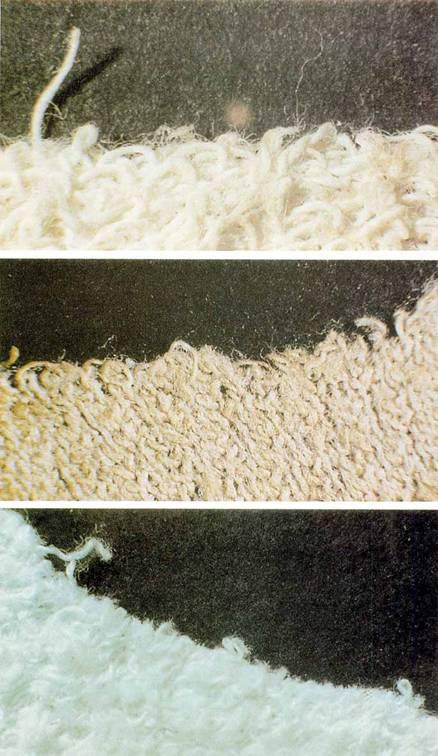

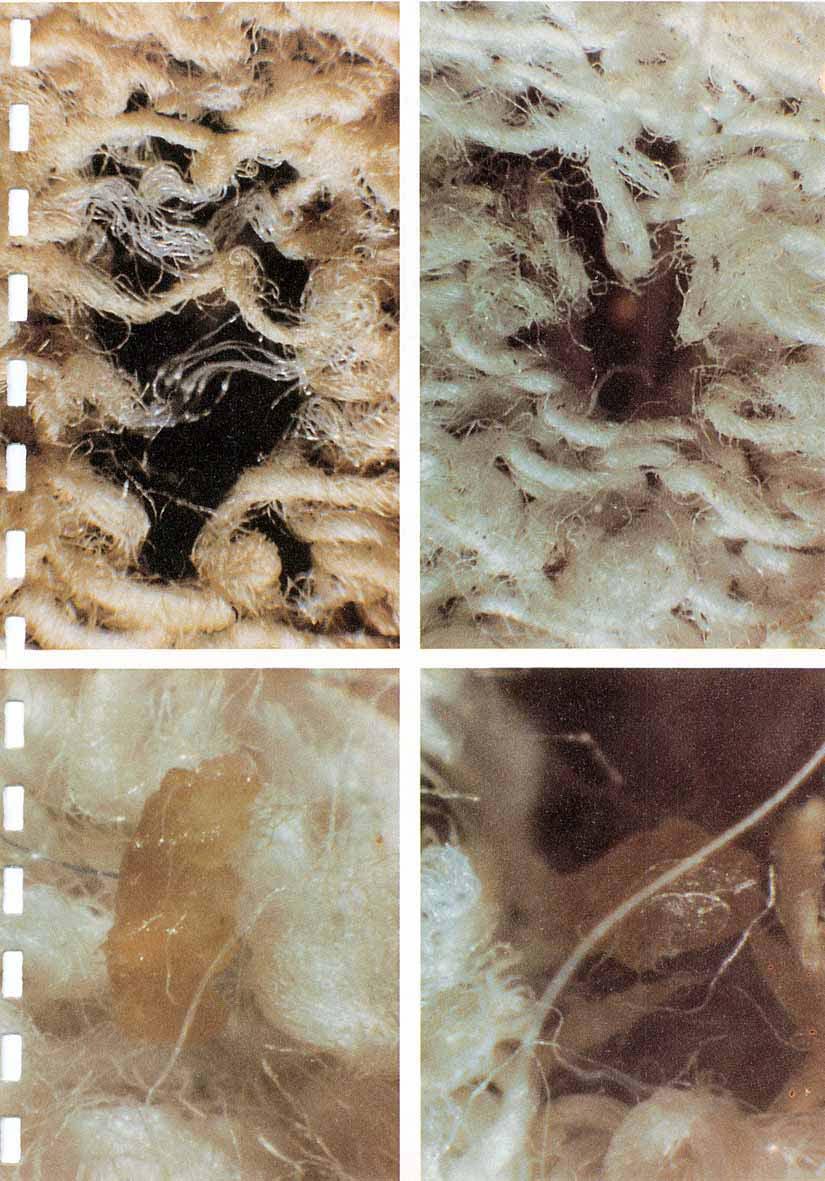

Photograph 12. (top) The damage seen in this photograph illustrates

a number of typical canine

damage features found in A Chamberlain’s jumpsuit. The zig—zag cut,

about 100mm long, is

formed from a series of smaller cuts, each about 12mm long, joined end

to end. The cut in the

sleeve of the Chamberlain jumpsuit (Photograph 2) is likewise formed

from a series of 12mm cuts.

Abrupt changes in the direction of cut, such as seen in the zig—zag

here are found in canine

damage patterns. Compare this with the abrupt change in direction of

the V cut in the

Chamberlain jumpsuit collar, shown in Photograph 3.

Photograph 13. (centre) The repeated arcs of damage in this fabric

sample (lower left) show the

damage resulting from the use of a dog’s central incisors in an action

reminiscent of a dog hunting fleas.

Photograph 14. (bottom left) The tuft shown in this photograph of

canine damaged fabric is still

attached to the main body of cloth by one or two fibres. Semi-detached

tufts such as these are

caused by small irregularities in the animal’s teeth, but do not

usually result from the action

of scissors. A comparable tuft in the Chamberlain jumpsuit can be seen

in Photograph 4.

Photograph 15. (bottom right) The tails of fabric shown here were

created when a dog secured the

fabric with a paw, grasped the other end of the cloth between her

central incisors

and raised her head (cf Photograph 5).

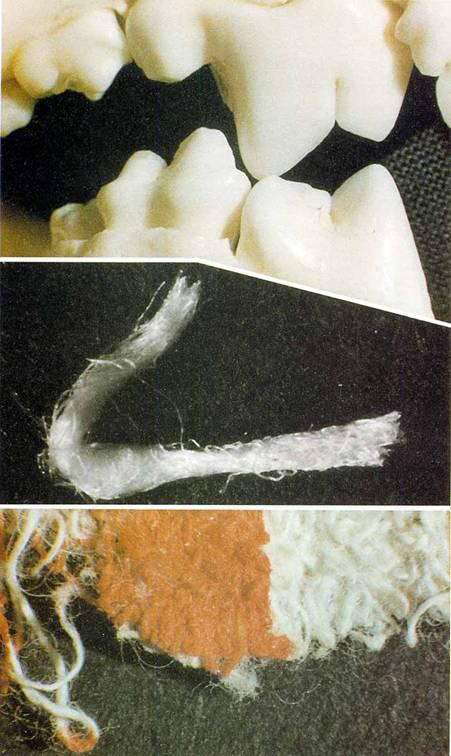

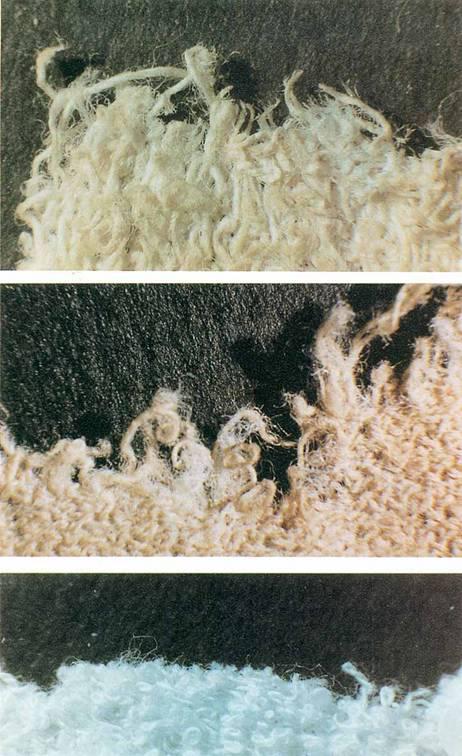

Photograph 16. (top) The appearance of a fabric edge cut by canine

teeth.

Photograph 17. (centre) The appearance of the cut fabric edge in A

Chamberlain’s jumpsuit.

Photograph 18. (bottom) The appearance of a scissor cut edge of

fabric.

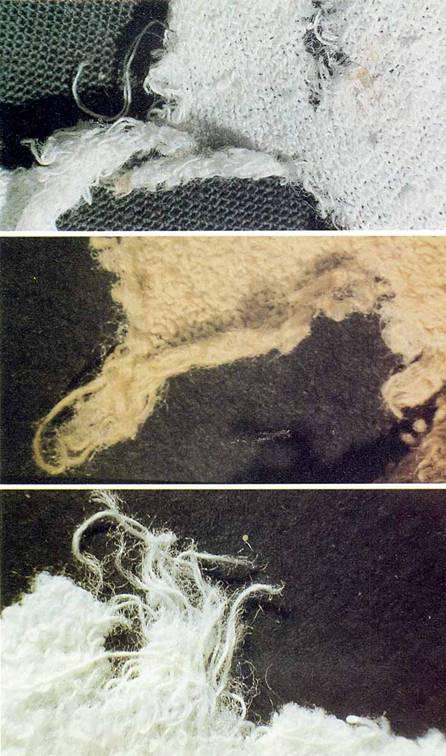

Photograph 19. A common appearance of fabric cut by canine

carnassial teeth.

Photograph 20. The appearance of the damage line in the sleeve of

the Chamberlain jumpsuit.

Photograph 21. The typical appearance of fabric cut by scissors.

This damage seen here is

from the jumpsuit cut by Sgt Cocks.

These photographs allow a 3 way comparison to be made between the

damage in the Chamberlain

jumpsuit and known canine damage. Such a comparison can be used to

determine whether a

difference exists between known scissor damage and the damage in the

Chamberlain jumpsuit

Photograph 22. (top) The damage seen here typically occurs when two

cuts made in the fabric

by a canine have not met and the animal has mauled the intervening

fabric. Note the curled

edge of the material, and the general matting of the threads where the

two cuts come together.

Photograph 23. (centre) The damage shown here is an enlargement of

the cloth tail seen in

the Chamberlain jumpsuit sleeve, Photograph 1, centre right. The

appearance of this damage

should be compared with that seen above.

Photograph 24. (bottom) This damage, from the Cocks jumpsuit

occurred when two scissor cuts

did not meet and the intervening fabric was torn apart. Compare this

with the damage seen

in both photographs above.

These photographs allow a 3 way comparison to be made between known

canine damage,

scissor damage and damage in A Chamberlain’s jumpsuit. They show that

over short

distances canine teeth can cut as well as scissors, and that features

other than the

presence of cuts are necessary to distinguish between scissor and

canine damage.

Photograph 25. (top left) A number of small isolated holes were

found in the centre back of A

Chamberlain’s jumpsuit. The court was told that if holes such as the

one shown here had

been caused by a dog they could not occur in isolation from other

holes or damage.

Photograph 26. (top right) One of a number of isolated holes found

in canine damaged fabric.

Photograph 27. (bottom right) A meat fragment embedded in the

fabric by the animal’s teeth.

Photograph 28. (bottom left) Small fragment of material seen in the

left arm of the Chamberlain jumpsuit.

These fragments should be compared with meat fragments embedded in

the fabric

by the animal’s teeth in Photograph 27.

By R D Bernett, K J Chapman, and L N Smith

Chamberlain Innocence Committee