|

Sarah Dazley (1819 – 5 August 1843),

later known as the "Potton Poisoner", was an English murderer

convicted of the poisoning of her husband William Dazley. Dazley

was suspected, but not tried, in the poisoning of her first

husband Simeon Mead and their son Jonah Mead in 1840. The murder

of William Dazley took place in Wrestlingworth, England.

Early life

Born in 1819 in the town of Potton,

Bedfordshire, Sarah Reynolds was the daughter of the town barber

Philip Reynolds and his wife Ann Reynolds. At the age of 7,

Dazley's father died and her mother went on to date a series of

men.

Following her mother's footsteps, the tall girl with long

auburn hair and big brown eyes married at the young age of 19 to

Simeon Mead. They lived in the town of Potton for two years before

moving to Tadlow in 1840. Shortly after the move, she gave birth

to their son Jonah. Jonah became ill and died at the age of seven

months. In October 1840, Simeon Mead died unexpectedly as well.

Murders

It didn't take much grieving for Dazley to get

over her first husband before marrying her second, and final,

husband William Dazley in 1841. Once married they moved to the

village of Wrestlingworth. Dazley invited teenage Ann Mead, Simeon

Mead's daughter, to live with her and her new husband. William

Dazley was opposed to the idea of Mead living with them so in

retaliation he became an avid drinker and hit Sarah. She went on

to tell one of her friends, William Waldock, that she would kill a

man who ever hit her.

William Dazley grew ill and his wife along with

Ann Mead began taking care of him. The local doctor, Dr. Sandell,

gave William prescriptions that helped him show signs of recovery,

while under the care of Ann Mead.

After seeing this Sarah started making pills of

her own for her husband. Mead was unsure what she was seeing and

didn't notice it as a problem at first. When William refused to

take the new pills, Ann took one herself to show him there was

nothing wrong. She was not aware that these pills contained

arsenic trioxide that Sarah had intentionally added. Once Sarah

saw Mead take the pill she scolded her for it. After taking it,

Mead became ill and shared similar symptoms with William, vomiting

and stomach pains. William continued to take Sarah's made up drugs

and died on October 30, 1842.

After his death, suspicion rose against Sarah

and the deaths of her two husbands and son. William Dazley's body

was exhumed and found to contain traces of arsenic. An arrest

warrant was then issued for Sarah Dazley, who fled to London.

Conviction

After being discovered in London by the

Superintendent of Blunden Biggleswade Police, she insisted she was

innocent of any crimes. Dazley claimed she had no idea about any

poisonings and never got a hold of poisons or anything of that

matter. She was arrested and returned to Bedford. The news of

William Dazley's death caused suspicion regarding the deaths of

Jonah and Simeon Mead as well, so their bodies were also exhumed.

Traces of arsenic were found in Jonah, but Simeon's body was too

decomposed to test.

Sarah Dazley was committed to Bedford Gaol on

March 24, 1843 and awaited her trial. Meanwhile, she used this

time to conjure up defenses such as William poisoned himself, or

he poisoned Jonah and Simeon so she poisoned William as revenge

for murdering her family out of his desires for Sarah.

On July 22, 1843, Sarah Dazley was tried for

the murder of William Dazley at Bedfordshire Summer Assizes. She

was not tried for the murder of her son Jonah, but the case was

kept if the first case against her were to fail. Dazley was found

guilty.

The chemists she bought arsenic from were able to testify

against her, as well as Ann Mead and neighbor Mrs. Carver. They

told what they had seen, including the pill making. William Waldock testified against Sarah about her statement that she would

kill any man that hit her, after making claims that William Dazley

had hit her. The Marsh test was used to detect the arsenic in

William Dazley's body and the result was used as forensic evidence

against Sarah. It only took 30 minutes for the jury to convict

Sarah for the murder of her second husband.

Death

Judge Baron Alderson sentenced Sarah Dazley to

hang. She was executed on Saturday, 5 August 1843, at Bedford Gaol.

She was the only woman to be publicly hanged at Bedford Gaol.

Thousands of people came to watch the execution. She became known

as the Potton Poisoner.

Sarah Dazley - a Victorian poisoner

CapitalPunishmentUK.org

Sarah was born in 1819 as Sarah Reynolds in the

village of Potton in Bedfordshire, the daughter of the village

barber, Phillip Reynolds. Phillip died when Sarah was seven years

old and her mother then embarked on a series of relationships with

other men. Hardly an ideal childhood.

Sarah grew up to be a tall, attractive girl

with long auburn hair and large brown eyes. However she too was

promiscuous and by the age of nineteen had met and married a local

man called Simeon Mead. They lived in Potton for two years before

moving to the village of Tadlow just over the county border in

Cambridgeshire in 1840. It is thought that the move was made to

end one of Sarah’s dalliances. Here she gave birth to a son in

February 1840, who was christened Jonah. The little boy was the

apple of his father’s eye, but died at the age of seven months,

completely devastating Simeon.

In October Simeon too died

suddenly, to the shock of the local community. Sarah did the

grieving mother and widow bit for a few weeks, before replacing

Simeon with another man, twenty three year old William Dazley.

This caused a lot of negative gossip and considerable suspicion in

the village.

In February 1841, Sarah and William married and moved

to the village of Wrestlingworth three miles away and six miles

north east of Biggleswade in Bedfordshire. Sarah invited Ann Mead,

Simeon’s teenage daughter to live with them. It seems that all was

not well in the marriage from early on and William took to

drinking heavily in the village pub.

This inevitably led to

friction with Sarah which boiled over into a major row culminating

in William hitting her. Sarah always had other men in her life

through both her marriages and confided to one of her male

friends, William Waldock, about the incident, telling him she

would kill any man who hit her. Sarah also told neighbours a

heavily embroidered tale of William’s drinking and violence

towards her.

William became ill with vomiting and stomach

pains a few days later and was attended by the local doctor, Dr.

Sandell, who prescribed pills which initially seemed to work, with

William being looked after by Ann Mead and showing signs of a

steady recovery. Whilst William was still bed ridden, Ann not

entirely realising what she was seeing at the time, observed Sarah

making up pills in the kitchen.

Sarah told a friend of hers in the village, Mrs

Carver, that she was concerned about William’s health and that she

was going to get a further prescription from Dr. Sandell. Mrs

Carver was surprised to see Sarah throw out some pills from the

pillbox and replace them with others. When she remarked on it,

Sarah told her that she wasn’t satisfied with the medication that

Dr. Sandell had provided and instead was using a remedy from the

village healer.

In fact the replacement pills were those that

Sarah had made herself. She gave these to William who immediately

noticed that they were different and refused to take them. Ann who

had been nursing him and had still not made any connection with

the pills she had seen Sarah making, persuaded William to swallow

a pill by taking one too. Inevitably they both quickly became ill

with the familiar symptoms of vomiting and stomach pains. William

vomited in the yard and one of the family pigs later lapped up the

mess and died in the night.

Apparently Sarah was able to persuade

William to continue taking the pills, assuring him that they were

what the doctor had prescribed. He began to decline rapidly and

died on the 30th of October, his death being certified as natural

by the doctor. He was buried in Wrestlingworth churchyard. Post

mortems were not normal at this time, even when a previously

healthy young man died quite suddenly.

As usual Sarah did not grieve for long before

taking up a new relationship. She soon started seeing William

Waldock openly and they became engaged at her insistence in

February 1843. William was talked out of marriage by his friends

who pointed to Sarah’s promiscuous behaviour and the mysterious

deaths of her previous two husbands and her son. William wisely

broke off the engagement and decided not to continue to see Sarah.

Suspicion and gossip was now running high in

the village and it was decided to inform the Bedfordshire coroner,

Mr. Eagles, of the deaths. He ordered the exhumation of William’s

body and an inquest was held on Monday the 20th of March 1843 at

the Chequers Inn in Wrestlingworth High Street.

It was found that

William’s viscera contained traces of arsenic and an arrest

warrant was issued against Sarah. Sarah it seems had anticipated

this result and had left the village and gone to London. She had

taken a room in Upper Wharf Street where she was discovered by

Superintendent Blunden of Biggleswade police. Sarah told Blunden

that she was completely innocent and that she neither knew

anything about poisons nor had she ever obtained any.

Blunden

arrested her and decided to take her back to Bedford. What would

be a short journey now required an overnight stop in those days

and they stayed in the Swan Inn, Biggleswade. Sarah was made to

sleep in a room with three female members of the staff. She did

not sleep well and asked the women about capital trials and

execution by hanging. This was later reported to Blunden and

struck him as odd.

The bodies of Simeon Mead and Jonah had also

now been exhumed and Jonah’s was found to contain arsenic,

although Simeon’s was too decomposed to yield positive results.

On the 24th of March 1843, Sarah was committed

to Bedford Gaol to await her trial and used her time to concoct

defences to the charges. She decided to accuse William Dazley of

poisoning Simeon and Jonah on the grounds that he wanted them out

of her life so he could have her to himself. When she realised

what he had done she decided to take revenge by poisoning William.

Unsurprisingly these inventions were not believed and were rather

ridiculous when it was William’s murder she was to be tried for.

In another version William had poisoned himself by accident.

She came to trial at the Bedfordshire Summer

Assizes on Saturday the 22nd of July before Baron Alderson,

charged with William’s murder, as this was the stronger of the two

cases against her. The charge of murdering Jonah was not proceeded

with but held in reserve should the first case fail.

Evidence was given against her by two local

chemists who identified her as having purchased arsenic from them

shortly before William’s death. Mrs Carver and Ann Mead told the

court about the incidents with the pills that they had witnessed.

William Waldock testified that Sarah had said

she would kill any man that ever hit her after the violent row

that she and William had. Forensic evidence was presented to show

that William had indeed died from arsenic poisoning, it being

noted that his internal organs were well preserved. The Marsh

test, a definitive test for arsenic trioxide had been only

available for a few years at the time of Sarah’s trial. Arsenic

trioxide is a white odourless powder that can easily pass

undetected by the victim when mixed into food and drink.

Since 1836 all defendants had been legally

entitled to counsel and Sarah’s defence was put forward by a Mr.

O'Malley, based upon Sarah’s inventions. He claimed that Sarah had

poisoned William by accident. Against all the other evidence this

looked decidedly weak and contradicted the stories Sarah had told

the police. It took the jury took just thirty minutes to convict

her.

Before passing sentence Baron Alderson

commented that it was bad enough to kill her husband but it showed

total heartlessness to kill her infant child as well. He

recommended her to ask for the mercy of her Redeemer. He then

donned the black cap and sentenced her to hang. It is interesting

to note that Baron Alderson had, at least in his own mind found

her guilty of the murder of Jonah, even though she had not been

tried for it.

During her time in prison, Sarah learnt to read

and write and began reading the Bible. She avoided contact with

other prisoners whilst on remand, preferring her own company and

accepting the ministrations of the chaplain. In the condemned cell

she continued to maintain her innocence and as far as one can tell

never made a confession to either the matrons looking after her or

to the chaplain.

There was no recommendation to mercy and the

Home Secretary, Sir James Graham, saw no reason to offer a

reprieve. The provision of the Murder Act of 1752, requiring

execution to take place within two working days had been abolished

in 1836 and a period of not less than fourteen days substituted.

Sarah’s execution was therefore set for Saturday the 5th of August

1843. A crowd variously estimated at 7,000 - 12,000 assembled in

St. Loyes Street, outside Bedford Gaol to watch the hanging. It

was reported that among this throng was William Waldock.

The New Drop gallows was erected on the flat

roof over the main gate of the prison in the early hours of the

Saturday morning and the area around the gatehouse was protected

by a troop of javelin men. William Calcraft had arrived from

London the previous day to perform the execution.

Sarah was taken from the condemned cell to the

prison chapel at around ten o’clock for the sacrament. The under

sheriff of the county demanded her body from the governor and she

was taken to the press room for her arms to be pinioned. She was

now led up to the gatehouse roof and mounted the gallows platform,

accompanied by the prison governor and the chaplain. She was asked

if she wished to make any last statement which she declined,

merely asking that Calcraft be quick in his work and repeating

“Lord have mercy on my soul”. He pinioned her legs, before drawing

down the white hood over her head and adjusting the simple halter

style noose around her neck. He then descended the scaffold and

withdrew the bolt supporting the trap doors.

Sarah dropped some eighteen inches and her body

became still after writhing for just a few seconds, as the rope

applied pressure to the arteries and veins of her neck, causing a

carotid reflex. Sarah was left on the rope for the customary hour

before being taken down and the body taken back into the prison

for burial in an unmarked grave, as was now required by law.

It was reported by the local newspapers that

the crowd had behaved well and remained silent until Sarah was

actually hanged. Once she was suspended they carried on eating,

drinking, smoking, laughing and making ribald and lewd remarks.

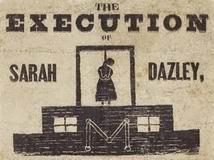

Copies of broadsides claiming to contain Sarah’s confession and

her last dying speech were being sold among the crowd, which

amazingly people bought even though she had made neither. You can

see a broadside about her hanging here. Note the stylised woodcut

picture that was modified to show a man or a woman as appropriate.

The 1840’s were a time of great hardship

nationally and yet Sarah, whilst hardly wealthy, did not seem to

suffer from this and it was never alleged that she was unable to

feed her child or that she was destitute. Extreme poverty in rural

areas did appear to be the motive in some murders at this time,

especially of infants. Sarah’s motive seems to be a much more evil

one, the elimination of anyone who got in the way of her next

relationship.

Sarah’s was the first execution at Bedford

since 1833 and she was the only woman to be publicly hanged there.

In fact Bedfordshire executions were rare events and there were to

be only two more in public, Joseph Castle on the 31st of March

1860 for the murder of his wife and William Worsley on the 31st of

March 1868 for the murder of William Bradbury.

Notes on the period.

Queen Victoria ascended to the throne in 1837,

at the age of eighteen and her reign saw a great deal of change in

the penal system. For the first thirty one years of it executions

were a very public event enjoyed by the masses. People would come

from far and wide to witness the spectacle, in some cases special

trains were even laid on! Broadsides were sold at many executions

giving the purported confessions of the prisoner and there was

considerable press interest, particularly where the criminal was

female.

Thirty women and two teenage girls were to be

executed in England and Scotland in the thirty one year period

from May 1838 to the abolition of public hanging in May 1868. Of

these twenty one had been convicted of poisoning (two thirds of

the total). Sarah Chesham was actually executed for the attempted

murder of her husband but was thought to be guilty of several

fatal poisonings as well.

Attempted murder ceased to be a capital crime

in 1861 under the provisions of the Criminal Law Consolidation Act

of that year. Mary Ann Milner would have made the total thirty

three had she not hanged herself in Lincoln Castle the day before

her scheduled execution on the 30th of July 1847. There were no

female executions in Wales during this time but a further ten

women were hanged in Ireland during the period, all for murder.

Sarah Chesham’s case prompted a House of

Commons committee to be set up to investigate poisoning. This

found that between 1840 and 1850, ninety seven women and eighty

two men had been tried for it.

A total of twenty two women were

hanged in the decade 1843 – 1852 of whom seventeen had been

convicted of murder by poisoning, representing 77% of the total.

There were no female executions in the years 1840 – 1842 in

England. This rash of poisonings led to a Bill being introduced

whereby only adult males could purchase arsenic.

Poisoning was

considered a particularly evil crime as it is totally premeditated

and thus it was extremely rare for a poisoner to be reprieved

whereas it was not unusual for females to be reprieved for other

types of murder, such as infanticide. One of the few poisoners to

be reprieved was Charlotte Harris in 1849 who had murdered her

husband but who pregnant at the time of her trial.

Sarah Dazley and the Merry family of Bedford1.

Mustrad.org.uk

The association of ballad-maker, ballad-seller and a particular

event tantalisingly glimpsed in the case of Coventry Tom2 can be

tentatively extended through that of Sarah Dazley, who was

executed at Bedford for poisoning her second husband, William.

Briefly, Sarah Dazley was baptised at Potton, Bedfordshire, in

1815, daughter of Philip and Ann Reynolds, and married a Simeon

Mead from Tadlow, just across the county border in Cambridgeshire,

in 1835. A son, Jonah, was born in 1840 but both Simeon and Jonah

died during that same year, Simeon aged but 24.

In the same year

again, Sarah then married William Dazley at Wrestlingworth, a

village near to Potton; but he, too, died soon - in 1842. It was

only a few months later that banns were read for Sarah Dazley and

George Waldeck of nearby Cockayne Hatley.

These circumstances might seem to have been, collectively, a

trifle unusual and there were also rumours about the death of

William Dazley. George Waldeck had himself been warned not to

fulfil his engagement and did, it seems, break it off. Consequent

to these uncertainties, the Bedfordshire coroner ordered

disinterment and traces of arsenic poisoning were found in the

bodies of both William Dazley and son Jonah (but not in the body

of Simeon Mead).

Eventually Sarah Dazley, having apparently absconded - in company

with one, Samuel Stebbings, described as a ‘paramour’3 - was apprehended in London where she

declared herself quite ready to face any closer investigation so

as ‘to clear her character’.

A trial was held back in Bedfordshire

and the jury gave the opinion that William Dazley had died ‘from

the effects of arsenic administered to him with a guilty knowledge

by Sarah Dazley, his wife.’ She was confined in Bedford gaol on

24th March 1843 and hung before a crowd estimated variously but at

least once in excess of some twelve thousand on August 5th 1843.4.

One newspaper report of the execution indicated that ‘a number of

inhabitants’ had made the journey to watch; and then the newspaper

followed with some clearly withering remarks about the lack of

suitable behaviour amongst the crowd and its connection with

ballad-selling, often typical of newspaper reports, justified or

not:

The crowd was reasonably orderly until after the victim was

suspended, when the ordinary debaucheries were carried on, "to

show the moral effects of the public examples," in these legalized

butcheries. Drinking, smoking, hustling and singing were among the

few displays of fine feeling, and the lawless mob were inclined to

no ordinary degree by the vagabond ballad-mongers bawling out the

last dying speech and confessions, and singing the copy of verses

made by the woman herself; all of which, we need not add, was

entirely false, and got up on the occasion, by a printer in the

town, as a harvest.5.

At this point it is useful to recall the alleged process of

making ballads on executions. Mayhew gave the information that the

case of any murder was presented in printed form in stages - life,

trial, confession and execution with, maybe, a sorrowful

lamentation added.6

This pattern is often found in newspaper accounts except

for the last-named which is likely to have given the most

opportunity for a separate ballad-printing; but prose accounts of

the event did sit side by side with verse. As noted in the

previous article in this series, Hindley printed just such an

amalgam in the case of Corder’s murder of Maria Marten.7.

A similar amalgam, for comparison, can be found centred on the

trial and execution (28th March 1866) of Mary Ann Ashford in

Exeter for the murder of her husband. One account of the Ashford

case, in terms reminiscent of the strictures on the Dazley

execution cited above, suggested that ‘there were 20,000 persons

present to gratify their morbid curiosity’.8.

Another included brief extracts from

correspondence between Mary Ann Ashford and a Frank Pratt (they

had, apparently, formed a liaison); more extracts, this time from

newspaper reports on William Ashford’s death; a reference to the

trial and the execution; and then a ballad, of whose style the

following stanzas are representative:

Good people all both far and near

Pray listen unto me

Mary Ashford she did die

On Exeter’s Gallows tree.

For the murder of her husband, dear,

William Ashford was his name.

She poisoned him at Clist Honiton,

And died the death of shame ... 9.

Following Mayhew’s description: the matter of confessions may be

considered. The presence of clergy was a ubiquitous feature of

executions and confession was certainly encouraged in keeping with

the solemnity of an occasion when culprits were preparing to meet

their maker. According to Mayhew, though, the confession of James

Rush, in a widely-reported case, was a ‘cock’ - a fabrication.10.

We have already seen, in the case

of Coventry Tom, how a supposed confession may have been contrived

from within the condemned cell, whether the occupant could write

or not. Nonetheless, newspapers did publish references to and some

full confessions. A report of the execution of Rebecca Smith in Devizes (23rd August 1849) ‘for murdering her infant child’

contains the following passage:

... Free from guilt and hypocrisy, she at once unhesitatingly

confessed her crime, and acknowledged the justice of the

punishment that awaited her, and frequently expressed a hope that

others would take a warning by her fate.11.

George Bentley, executed at Stafford in 1866, ‘made a

confession’ to the prison authorities ‘and he fully acknowledges

the justness of the sentence that has been awarded.’12. Catherine Foster, executed in Bury St

Edmunds in 1847, had her confession witnessed by the prison

governor and the prison chaplain and then published.13.

Even

after public hanging ceased to be a public spectacle in 1868,

confessions were published. That of William Bull, like Sarah Dazley, executed at Bedford (1871), was made on two separate

occasions, the first witnessed by the governor of the gaol and a

warder and the second, made a week later, in the presence of the

governor and the prison chaplain.14. That of Henry March, who was

executed in Norwich in 1877, was also published.15.

There are, too, ballad-printings of confessions such as that of

Thomas Drory (mentioned elsewhere here) who, supposedly wrote of

Jael Denny, his victim, that

I in a field did her entice

And with a rope I did her kill ...

and, after begging forgiveness for his crime, continued:

Farwell my friends and neighbours too,

Adieu my tender father dear ... 16.

Clearly, though, the device of confession, in this case, was

simply another way of casting the details of the case.

Where Mary Ann Ashford was concerned, the Western Morning News

indicated that she ‘refused to make a detailed confession’17 and there is

no mention of one in the ballad either.

As for Sarah Dazley, there are contradictions which cannot be

resolved. She always maintained her innocence and, in one report,

is supposed to have protested to her gaolers right until the last

that she did not know that her husband had taken poison and, then,

seeming to comprehend how things were going to turn out, despite

her protestations, ‘Pray do not leave me,’ she continued, ‘but be

as quick as you can’.

In another report she is reputed to have

answered the Minister and Gaoler ‘severally’ asking if she had

anything to say by replying: ‘I have nothing to say’ after which

she only repeatedly uttered the words, ‘Lord have mercy on my

soul’.

Yet another newspaper report gave the

information that, apparently, she refused to say anything at all

during her last hours and the press ‘by the under-sheriff’s

deputy, were excluded from the scene, where the last words of the

prisoner, about to enter the presence of her God, should have been

carefully noted’.18.

Further, the first newspaper report cited in

this piece indicated that as ‘the unhappy woman was launched into

eternity amidst the groans, sighs and tears of the spectators’

most ‘were greatly shocked at the idea of her not having made any

confession’. This may or may not be hyperbole.

There is another aspect to consider. The depositions in the Dazley

case would have offered prime material for adaptation; and we do

know that ballad-makers used newspaper accounts. One of Mayhew’s

informants, for instance, told him that, of one ballad, ‘that bit

was taken from a newspaper. Oh, we’re not above acknowledging when

we condescends to borrow from any of ’em’.19. Mayhew also

commented that ‘The narrative, embracing trial, biography, &c., is

usually prepared by the printer, being a condensation from the

accounts in newspapers ... ’.20.

The question all the time is to do with the composition and

distribution of ballads. Much evidence, some as noted here and in

the previous article, does refer to the practice. At Aylesbury, in

1845, men were seen to be ‘turning a penny’ by the sale of a

description of ‘the execution of John Tawell this morning’.21.

The Times report on

the execution of Sarah Chesham for the murder of her husband

Chelmsford in 1851 noted ‘hawkers of ballads and "true and correct

accounts" of the execution ... ’ (and added, in an almost

throwaway line about the behaviour of the crowd, that ‘all kinds

of edibles appeared ... ’).22. At Maidstone, in 1867, at the double execution of Ann

Lawrence and James Fletcher,

There were the usual hawkers of "last dying speeches and

confessions," and other itinerants who live by similar scenes.23.

The Northampton Mercury, indeed, in an account reminiscent of the

one printed by the Banbury Guardian, reported that at the Dazley

execution, ‘Vagabonds of both sexes were bawling out the last

dying speech and confession of the woman of "three" murders, when

in truth she did not acknowledge one.’24. It is a matter of no little

conjecture that an observer might well describe what was expected

to happen and not necessarily what actually happened in something

of the same way that some ballads would appear to have been

concocted and others put out before the ‘drop’. Still, where Sarah Dazley is concerned, references to the selling of a ballad are

clear enough.

In terms of probability and circumstance, then, the odds are that

a ballad about Sarah Dazley was contrived. If so, some or other of

the features described here would most likely have appeared.

Regret for the crime, we would expect. According to the printed

ballad, Harriet Tarver, executed at Gloucester in 1836 for

poisoning her husband, hoped that her ‘orphan child’ would take

warning and shun ‘vice and bad company’ and

You married women wheree-er [sic] you be

I pray take a warning by me

Pray love your husband and children to [sic]

And God will his blessing bestow.25.

Any reference to the actual crime seems, usually, to have been

somewhat restrained in character. Henry March, for instance, fell

out with a ‘shopmate’ and ‘With a large bar of iron his life took

away’. Mary Ann Cotton, convicted of a series of murders of

husbands, children and neighbours, ‘watched them yield their

latest breath’.26. In the

case of Sarah Chesham,

On the twenty-eighth of May,

The wretched woman she did go

To a shop to buy the fatal poison,

Which has proved her overthrow;

The dreadful dose she gave her husband,

Soon after which Richard Chesham died ... 27.

It was left to newspaper accounts to stretch out the lurid

details.

All this would allow any ballad-maker latitude to compose an

attractive (salacious?) narrative; to escape fidelity to

actuality; and thus to steal a march on ostensibly accurate

newspaper accounts; and to have been able to choose a particular

viewpoint, whether that of an onlooker or of the principal, for a

more effective dramatisation of the event.

Similarly, the idea of

last words and confessions, palpably not always capable of clear

verification, would still attract a ballad-maker’s skill and still

invite an audience, even a prurient one. We know this, at the

least, from the continued popularity of execution ballads which

regularly referred in their titles - somewhat in the manner that

the Drory case was presented - to exactly the ‘last words and

confession’.28.

Where the unfortunate Sarah Dazley was concerned and the

possibility of a ballad having been made on her execution, we do,

in fact, have information about ‘a printer in the town’ whose

activities date from 1818 through one, Clarke Barber Merry,

‘Printer, Bookseller, Stationer, Paperhanger, Bedford’, who, in

1820, printed election pieces concerning local politicians.29.

In 1821 the Bedfordshire Quarter

Sessions Records included a letter from a C B Merry asking the

Magistrates to consider his services for printing purposes. Pigot’s Bedford directories listed Clarke Barber Merry as printer,

High Street, Bedford, in 1830 and in 1839. There are more recorded

manifestations of the family concern throughout the middle years

of the century, including a song-text, Trelawny and Victory to the

tune of With Helmet on his Brow, printed in 1854. We do also know

of broadside ballad-sheets with the Merry imprint on them - there

are ten such in the Bodleian collection30 - and certain details on

the sheets and, even more so, dates associated with one or two of

them, give a further perspective on the progress of the firm

through the century.

One of the ballad-sheets has the initials, ‘C

B Merry’, on it. Another places The Drummer Boy of Waterloo,

positing a fairly obvious date, alongside Woodman, Spare That Tree

which latter dates from 1837.31. A third focuses on the subject of the siege of Lucknow, which took place in 1857. Taking these factors together

and noting that there are shades in between, the point here is

that a period of time during which the Merry imprint flourished is

clearly indicated.

We know that Clarke Barber Merry’s sons, John Swepson Merry and

William Merry, were printers but William died in 1846 and,

moreover, John Swepson was not recorded in the 1851 Bedford

census.32. There may be one

answer to an implicit mystery: the initials, ‘M. A.’, appear on

five ballad-sheets. These seem to have belonged to Mary Anna

Merry, daughter of Clarke Barber Merry, and baptised in 1830. It

is not possible, at this stage, to be clearer about Mary Anna’s

involvement. It does, nevertheless, look as though Clarke Barber

Merry had passed on the business since, although he was listed in

the 1851 census, it was not as a printer. In 1861 he was listed as

‘Printer, Retired.’

Even more pertinently, we also know that it was John Swepson and

William who were involved in the Sarah Dazley case. For, in this

respect, a discovery was made recently, that of a poster situated

in the Bedford Museum which revealed a simple picture with the

legend ‘The Execution of Sarah Dazley’ on it and accompanied by

the initials of J S and W Merry.

Frustratingly, however, that is all ... no text concerning Sarah

Dazley appears to have survived.33. As in the case of Coventry Tom, clinching

evidence of a specific event and an attendant ballad simply eludes

our grasp.

Roly Brown - 28.2.03

Massignac, France

Footnotes:

1. There are, as usual, several debts to be acknowledged and I

would particularly like to thank the staffs at the under-mentioned

libraries for their provision of material and help with

consultation during a number of visits: Plymouth public library

for the Tavistock Gazette, The Western Morning News and the

Western Daily Mercury; the West Country Local Studies Library,

Exeter for the Exeter Flying Post; Wiltshire Public Record Office,

Trowbridge for The Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette, The Salisbury

and Wiltshire Herald and the Sherborne Mercury; both Trowbridge

and the Oxford Local Studies Library for The Northampton Mercury;

and Oxford also for Jackson’s Oxford Journal and The Banbury

Guardian (other material was made available in all these libraries

as well); the Essex Public Record Office for The Times and the

Chelmsford Chronicle articles; Chris Smith and the Norfolk Studies

Library for sending me the Norfolk Chronicle and Norwich Gazette

reports; and Joanna Pateman and the Kent Record Office for

forwarding the Maidstone and Kentish Journal newspaper accounts

and Deborah Saunders and the Centre for Kentish Studies for

additional information, all cited in the text below. I also have

to thank the Bodleian Library for permission to quote from copies

of broadsides included in its Allegro archive and Cambridge

University Library for permission to quote from copies of

broadsides from the Madden collection. Access to the Madden

collection was most often gained through the auspices of the

Vaughan Williams Memorial Library at Cecil Sharp House and I would

like to thank the EFDSS and especially Malcolm Taylor and his

staff at the library for patience and help.

2. See Musical Traditions, Article 131, January 2003.

3. Bedfordshire Mercury and Huntingdon Express, April 1st 1843

(see end for acknowledgements).

4. Jackson’s Oxford Journal, Saturday August 12th 1843, p.4, gave

its estimate as 10,000.

5. Banbury Guardian: Thursday 10th August 1843 - which newspaper

spelled the name as ‘Dazeley’ whereas other newspapers left out

the first ‘e’.

6. See Henry Mayhew, Life and Labour of the London Poor (London,

Frank Cass and Co. Ltd., 1967, Vol. I), pp.280-285.

7. The murder took place in 1828. Hindley’s piece was first

printed by Catnach and is found on p.80 of The History of the

Catnach Press (first published in 1887 and re-issued in Detroit by

The Singing Tree Press, 1969).

8. Tavistock Gazette, Thursday 29th March 1866 unpaginated. The

Exeter Flying Post (28th March 1866, p.8 - though the report was

written on Wednesday March 28th) followed a similar line,

referring to ‘every species of vice and immorality’ amongst the

crowd.

9. I am indebted to Sue and Phil Warrilow (Braunton, Devon), for

forwarding a copy of this piece which is included in a Devon

Library Services Theme Pack, Law and Order (n..d.). The exact

source of the printing has not yet been identified.

10. Mayhew: op cit, p.281; and for a note on this phenomenon, the

previous piece in this series.

11. See Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette for Thursday August 23rd

1849, p.3. Identical reports can be found in The Salisbury and

Wiltshire Herald (Saturday August 25th 1849, p.4) and the

Northampton Mercury, (Saturday September 1st 1849, p.4). This

succession of reports is an interesting indicator of how news may

have travelled and in what form.

12. Western Daily Mercury 28th March 1866, p.2.

13. The Norfolk Chronicle and Norwich Gazette, 24th April 1847.

14. Bedfordshire Times, 4th April 1871. This execution took place

behind closed doors; but there were, it is reported, numbers of

people gathered outside the prison walls.

15. See The Norfolk Chronicle and Norwich Gazette, 24th March

1877.

16. Confession of Thomas Drory, Bodleian Allegro archive, from

Firth b.25(141).

17. Western Morning News, Thursday March 29th 1866.

18. Bedfordshire and Huntingdonshire Express, 5th August 1843.

19. Mayhew: op cit, p.225.

20. Ibid, p.281.

21. Banbury Guardian, 4th April 1845. The execution took place on

28th March 1845. It was also reported in Jackson’s Oxford Journal

(Saturday March 22nd 1845, p.4 and Saturday March 29th 1845, p.3)

where, incidentally, a confession was cited; and in Northampton

Mercury (Saturday April 5th 1845, p.4) where Tawell’s

acknowledgement of the murder was noted but not a confession.

22. The Times, 26th March 1851 (unpaginated). This was also the

occasion of the execution of Thomas Drory for the murder of Jael

Denny. For a report on both the Drory and Chesham executions see

the Chelmsford Chronicle, 28th March 1851, and for a separate

report on Drory see the same newspaper, 14th March 1851. Drory, it

seems - or, rather, Jael Denny, the victim - did not do well for

Mayhew’s informant because ‘The weather coopered her, poor lass!’

- presumably he was travelling the country ... Nonetheless he

still expected to make money from Drory: which suggests that old

news would be re-cast (Mayhew, op cit, p.225). Sarah Chesham is

not mentioned in Mayhew’s accounts.

23. See Maidstone and Kentish Journal, 12th January 1867, p.2, the

first of two reports on these executions in the same journal, the

second put out two days later.

24. Northampton Mercury, Saturday August 12th 1843, p.4.

25. I am indebted to Roy Palmer (Malvern) for forwarding me a copy

of this ballad, printed by Willey of Cheltenham and to be found in

the Madden collection. The full title given by Willey was:

An affecting Copy of Verses

Written on the Body of Harriet Tarver

Who was Executed April 9th 1836, at Gloucester, for Poisoning

her Husband in the town of Camden

- Camden being Chipping Camden.

26. The March and Cotton ballads can be found in the Bodleian

Library’s Allegro archive: taken from sources as follows: Harding

B 14 (234) - no imprint; and Firth c 17(98) - no imprint. Mary Ann

Cotton was executed on 24th March 1873.

27. Hodges (London) imprint, Bodleian Allegro archive, from Firth

b 25(382).

28. See, for example, the Disley (London) printing of Lamentation,

Confession and Execution of Muller, Bodleian Allegro archive

(Johnson Ballads 316). Muller was executed in 1864 for the murder

of one, Cooper, in a railway carriage.

29. He was baptised December 8th 1786 in Moulton, Northamptonshire

and died on 15th September 1868. The reference to ‘a printer in

the town’, it should be recalled, is in the first newspaper

account quoted in this article.

30. The Madden collection has no items at all from Bedfordshire.

31. This is as a first publication of Woodman ... . The words

actually date from 1830 and a poem by an American, George Pope

Morris, and the music was by Henry Russell, English-born but

living in America when he collaborated with Morris. Russell came

and went to America and in 1842 was giving a series of concerts in

England. It may have been then that Woodman ... was first heard in

England and that printings appeared subsequently (for more brief

details of Russell’s career see Derek Scott: The Singing Bourgeois

... Aldershot, Ashgate Publishing Company, 2001, pp.39-40). It

should be said that Waterloo material could well have been

retrospective as, for instance, was much to do with Nelson and

Trafalgar ... that is to say, given the obvious caveat, put out

much later as a commercial proposition.

32. This might conceivably have been a temporary blip: he could

have been away from home during the census take. More information

is emerging in connection with John Swepson and this will form

part of another piece in this series.

33. I am greatly indebted to Susan Edwards, archivist at the

Bedford Public Record Office, who has assembled a mass of detail

concerning Sarah Dazley’s case, and who sent me a copy from which

some references are taken in order to supplement the first account

in the Banbury Guardian above and that of others found; and who

also furnished me with details of the Merry family. It is very

much due to the efforts of the Bedford Record Office that

information contained in this article has come to light.

|