Wynekoop Murder!

How Woman

Doctor Killed Son's Wife

A Bizarre

Crime with Prison the Penalty

By

VIRGINIA GARDNER

CHAPTER

I.

Death

in the Doctor's Office

"WHEN I

went to my office I found Rheta on the operating table. She was

dead."

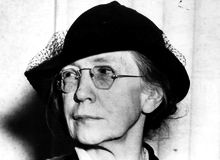

Dr. Alice

Lindsay Wynekoop, 62 years old, respected citizen, physician, and

veteran of the suffrage and other women's movements of two decades

ago, finished speaking.

"Well, Dr.

Alice, may I view the remains?" replied Thomas J. Ahern, the

family undertaker, who followed Dr. Wynekoop down a flight of

steps into her basement office.

In the

grim, old-fashioned operating room, on an antique operating table

cushioned with worn black lether, [sic] lay the blanketed figure

of a pretty red-haired girl. It was that of Dr. Wynekoop's

daughter-in-law, Rheta Wynekoop.

"Have you

notified the police?" Ahern asked politely.

"No,"

answered Dr. Alice with an imperious gesture. "I don't want any

publicity."

"Well,

this is a murder," said the rotund undertaker, and walked

upstairs, picked up a telephone, and called the police.

CHAPTER

II.

Revolver Beside the Body

POLICEMEN

Arthur R. March and Walter Kelly of Fillmore street station were

cruising in a squad car when the radio command came to go to 3406

West Monroe street, where a murder was reported.

It was "a

mild, clear evening," March later testified, on that night of

Tuesday, Nov. 21, 1933.

It was

9:25 o'clock when Undertaker Ahern received a telephone call from

Dr. Wynekoop summoning him to her home. It was 9:55 o'clock when

members of the squad car detail arrived at the Monroe street

address, an old dwelling of red brick, grimy with the years'

accumulation of soot.

The

policemen hurried up the four stone steps leading to the porch and

rang the bell, which sounded emptily from within. The door was

cautiously opened and the slightly protruding pale blue eyes of a

short, dumpy little woman peered at them.

They

stepped inside. Behind the little woman, who was Miss Enid

Hennessey, teacher in the John Marshall High school and for ten

years a boarder in the sixteen-room house, was the gaunt, gray-haired

figure of Dr. Wynekoop.

Dr.

Wynekoop received the policemen imperturbably. With her were

Ahern, the undertaker, and Dr. John M. Berger of Oak Park, who had

known Dr. Wynekoop more than fifteen years. She had summoned him

after she found the body.

The little

group filed down the stairs to the basement--the policemen, the

woman doctor with her intelligent face and frank manner, and the

short, bustling woman with her suspicious blue eyes, the doctor,

and the undertaker.

In the

basement, containing eight rooms and two hallways, were the

doctor's office and operating room. They passed by the office with

its old-fashioned roll-top desk, stuffy lether [sic] upholstered

furniture, and thick medical books and entered the operating room

across the hall.

On the

operating table they saw Rheta Wynekoop's body lying on its left

side, her face on a small pillow. Covering the slight figure of

the 23-year-old girl was a blanket, neatly folded the long way and

tucked about the body as if by gentle hands.

Policeman

March removed the blanket. The body was nude save for a pink slip

rolled about the waist, a chemise, and stockings. Above this wisp

of underclothing was a wound in the back over which blood was

clotted. Blood was oozing from the mouth and dropping to the

floor. The two sheets on the operating table beneath the body were

saturated with blood, as were her garments.

A folded

towel, damp, was under the mouth. Beside the pillow, was a

.32-caliber revolver, wrapped in gauze. Near by were a folded

sweater, a brown skirt, a pair of woman's shoes. A handkerchief

lay on the operating table near the body. Dr. Wynekoop herself

pointed out a chloroform bottle on a nearby washstand. An

anesthetic mask was in plain view. Policeman March touched the

body. Rigor mortis had set in. Warmth leaves the human body from

three to six hours after a death.

CHAPTER

III.

Points

to Robbery as Motive

DR.

WYNEKOOP said she had found the body at 8:30 o'clock that night.

She called her daughter, Dr. Catherine Wynekoop, then 25-year-old

resident pediatrician at the Cook County hospital, and told her to

come home. Dr. Catherine replied that she was busy. Dr. Alice said

that something terrible had happened. "What, mother?" the younger

woman asked. Her mother said, "Rheta has been shot and is gone."

Dr. Catherine hurried home. At 9:30 they knocked on Miss

Hennessey's door and told her Rheta was dead.

The

elderly woman physician told police it "must have been done by

someone looking for money." She showed an open drawer in her desk

in which a box in the rear held currency and stamps. This had been

looted, she said, of $6.

She

admitted ownership of the gauze-enveloped revolver beside the

body. In a box behind her cash box was another. There were unfired

cartridges in it.

She had

received the revolver from her son, Earle, Rheta's 24-year old

husband, she admitted, before he departed for the Grand canyon,

Arizona, with a companion to take color photographs. He had gone

away on Nov. 13.

Twice

before her home had been robbed, she told the police. On Oct. 20

thieves had broken in and taken $100. Both times drugs were taken.

She had not reported these incidents, she said, because she knew

"money couldn't be identified." To reporters she said that it was

out of consideration for Rheta and her delicate health that she

did not report the matter, as policemen about the house would

upset the girl.

The desk

drawer, although open, appeared in order. The windows and doors

leading from the outside into the basement were all closed, and

the doors were locked.

CHAPTER

IV.

Police

Find Love Letter

UNDER a

pile of other papers in Dr Wynekoop's bedroom on the second floor

of the gloomy old house police found a letter in feminine

handwriting. They were looking for evidence which might shed light

on Rheta's life, although Dr. Wynekoop assured them that Rheta and

Earle had lived happily together with her since their marriage in

1929. It appeared to be a love letter, and the police considered

she might have an admirer unknown to her mother-in-law. Dated

"Sunday night," and written in pencil, the letter read:

"Precious:

I'm choked. You are gone--you have called me up--and after ten

minutes or so I called and called. No answer. Maybe you are

sleeping. You need to be, but I want to hear your voice again

tonight--I would give anything I have--to spend an hour in real

talk with you tonight--and I cannot--good night"

A phone

call to the slain girl's father, B. H. Gardner, a respected flour

and salt broker of Indianapolis, confirmed Dr. Wynekoop's

statement that Rheta was a sensitive girl, a trained violinist,

who had little social contact outside the life which went on in

the Wynekoop home, where she cooked and helped with the housework

and pursued her interests in music.

At 1 a. m.

Dr. Wynekoop revealed a telegram to the police after they had

learned of it from other sources. It was from Earle and was sent

from Peoria at 3:47 p. m. the day of the murder. It had been

received at the house by Miss Hennessey at 7:55 o'clock. W.

Russell O'Banion, Western Union messenger, had delivered it.

Previously, at 4:27 p. m., John Brennock, another messenger, had

called with it. He had no response when he rang the doorbell,

although he had seen lights burning in the basement and on the

first floor.

It was not

until the next day that Dr. Wynekoop revealed that the mysterious

letter was written by her to Earle. She said with flashing eyes

that it was "a love letter from a mother to her son." Later

psychiatrists were to find it significant, and at least one

declared it indicated a possible "Œdipus complex," or at any rate

an exaggerated maternal feeling.

Developments were swift the next day. From Kansas City came word

that Earle had been there when he learned of his wife's death that

morning and had set out at once for Chicago. Stanley Young of

Chicago, a nephew of George E. Q. Johnson, former United States

district attorney, who was Earle's companion on their interrupted

trip to Arizona, provided Earle with an ironclad alibi.

In Kansas

City Young revealed also that Earle and his mother had held a

secret rendezvous the evening before the murder. For some reason,

Young said, Earle had not wanted Rheta to know he was in Chicago.

Rheta thought he already was on his way west. Actually they had

left Chicago at 8 a. m. Tuesday, the day of the murder, stopping

in Peoria and continuing to Kansas City. Dr. Wynekoop admitted

that she had met her son the previous night at 67th street and

Kedzie avenue and talked "about his trip."

Early

Wednesday morning an inquest was begun in Ahern's undertaking

rooms, 3246 Jackson boulevard. Coroner Frank J. Walsh briefly

questioned the elderly Dr. Wynekoop.

"Did Rheta

have any insurance?" Coroner Walsh asked.

Composed,

her manner one of intelligent cooperation, the witness replied:

"I know

she had no insurance. She tried to obtain policies from several

companies, but the negotiations fell through."

Coroner

Walsh leaned toward reporters near by and whispered that Rheta had

been insured for $5,000 with the New York Life Insurance company,

that the policy had a double indemnity clause in case of death by

violence, and that Dr. Alice Wynekoop was the beneficiary. Another

double indemnity policy for $1,000 named Earle and Catherine as

beneficiaries.

Moreover,

the mother-in-law had obtained the larger one against the girl's

life a month before the murder and had herself paid the first

premium. This she did despite her grim financial situation. At the

time she owed her grocer, her butcher, and the family undertaker.

There was a $3,500 mortgage on the Monroe street home, and on Oct.

31 she had a bank balance of only $26.

An

undertaker's unpaid bill was for the funeral of an adopted

daughter, Mary Louise, who died in March, 1930.

Back in

1910, at the peak of her career, Dr. Wynekoop had addressed the

Mothers' congress and Parent Teachers' association convention at

Rockford and urged that every family adopt one child, as she had

done, as an "act of humanitarianism" and a "duty toward the race."

This was in reply to a widely published statement by Olive

Schreiner, novelist, who was much in vogue then, that one child

for each family was sufficient. Dr. Wynekoop, for her speech,

received considerable publicity, a picture of the then beautiful

woman physician and her four curly haired children being published

in newspapers.

Three

other deaths had occurred in the Monroe street house in four

years. Dr. Frank Wynekoop, husband of the woman physician and,

like her, a former professor at a medical college which later

became the University of Illinois medical school, had died of

heart disease New Year's day, 1929. The deaths of Miss Hennessey's

85-year old father and Miss Catherine Porter, a spinster of Dr.

Wynekoop's age and a patient of hers, who left her $2,000,

followed that of Dr. Frank Wynekoop.

CHAPTER

V.

Dr.

Alice Undergoes Quiz

AFTER the

inquest Dr. Wynekoop was taken to the Fillmore street station and

questioned by Captain Stege. She repeated her claim that she had

"loved Rheta as if she were one of my own." She related her

actions the day of the murder. She said that after lunch she went

to shop on Madison street, arriving home at 4:30 o'clock.

Miss

Hennessey came in about 6 o'clock and they ate dinner, leaving

some of the food for Rheta, whose place was set at the table. It

was at dinner, Miss Hennessey said, that they discussed Eugene

O'Neill's drama, "Strange Interlude," a drama dealing with the

overweening mother love of a strong willed woman. Dr. Wynekoop

asked Miss Hennessey if such "trash" was given students to read.

The doctor

then sent Miss Hennessey to a neighborhood drug store on an

errand. Returning, Miss Hennessey noticed Rheta's coat, hat, and

purse on a chair. She called Dr. Wynekoop's attention to them, and

the doctor replied that Rheta had another coat and hat and

probably had worn them.

Dr.

Wynekoop and Miss Hennessey then talked of the latter's condition

of hyperacidity, and Dr. Wynekoop said she would get some medicine

for her. She went downstairs but did not return at once, Miss

Hennessey went to her room. It was at that time, Dr. Wynekoop said

(8:30 p. m.), that she discovered Rheta lying on the operating

table.

Mrs.

Veronica Duncan, a pretty brunette who lived next door at 3408

Monroe street, had seen Rheta Wynekoop alive at 3 p. m.

The day

after the inquest, Thursday, Dr. Thomas L. Dwyer, then coroner's

physician, announced the results of his post-mortem. He found that

chloroform had been administered to the girl, causing burns around

the mouth. He said the lungs were filled with blood, showing that

when the bullet had entered her body she was still alive.

Dr.

Dwyer's report stated that no holes were found in the girl's

clothing, and that first-degree powder burns surrounded the wound,

meaning she was shot with the muzzle of the weapon pressed against

her.

"Apparently she had taken off her clothes," said Captain Stege,

"probably as she sat on the edge of the operating table, and

dropped them at her feet. She had then lain back, as if submitting

to an examination. While in that position, apparently, the killer

placed her under an anesthetic, turned her half way on her face,

and fired the shot. Finally the killer, in an apparent fit of

remorse, tried to stanch the blood flowing from her mouth, and,

seeing she was dead, wrapped her body in a blanket."

Through

long hours of questioning Dr. Wynekoop maintained that she had

obtained the insurance policies, which she now admitted, only

because of her anxiety that Rheta be assured her health was good.

Rheta, she said, was morbidly worried over her condition, as she

was underweight, and her mother had died of tuberculosis.

Earle

Wynekoop, tall, well built; auburn-haired, and well dressed,

returned to Chicago Thursday morning. He first visited the

mortuary and viewed the body of his wife.

"I was

unhappy in my married life." he said, "and mother knew it"

Unhesitatingly he admitted keeping company with other women. Some

of these were questioned by the police. From one they learned he

had kept a notebook with fifty names and addresses of girls he

considered attractive, classifying them methodically as to their

charms.

Several of

his extramarital sweethearts said that he posed as unmarried. He

apparently had played the rôle of a Don Juan while employed at the

World's Fair. To an attractive girl employé of a concession he

gave a ring which police believed to be the engagement ring he had

given his wife. This young woman, learning Earle was married,

reproached him with the fact. He admitted it.

"He told

me he married her [Rheta] and found out later that her mother and

aunt had died of tuberculosis," she told the police. "He said the

matter was out of his hands, that it was in his mother's. I asked

him where she was, and he said she was put away. He didn't say

where."

To this

girl he had proposed marriage. Still another girl had kept a

midnight date with him the night before the murder.

Throughout

the day the police questioned Earle. At 10:45 o'clock that night

they again took his mother into custody. She was at the mortuary,

where she had gone to say a last farewell to Rheta.

With Earle

and his mother in adjoining rooms the grilling proceeded. Dr.

Alice's inquisitors applied the lie detector. She said scornfully:

"I have high blood pressure, it will not work." They found this

was so.

Veteran

detectives, police officials, and three psychiatrists matched

their wits in vain against the weary but still unfaltering mind of

the woman. She was aged, ill, she had slept almost none since the

night before the murder, Monday. This was Thursday night. At 6

o'clock Friday morning they gave up for the time being and she was

taken to the Racine avenue station to sleep in the women's

quarters.

Earle,

comparatively fresh, then broke. The first trace of it was when he

said desperately:

"Mother

blamed Rheta, as mothers will, for my unhappiness, and its barely

possible that she might have had a motive for--but no. No! My

mother could not have done that."

Well,

then, what about yourself?" Captain Stege pressed. "It was your

mother or you. Speak up."

Earle

sobbed wildly, "I will sign an iron-bound confession to save the

one I suspect."

Dr.

Wynekoop was allowed to sleep until 7:30. As she was leaving the

Racine avenue for the Fillmore street station a reporter told her

it was rumored that Earle had confessed. Clasping her hands

together, tears filled her eyes.

"This is

the happiest moment of my life," she said.

Police

interpreted this to mean that she was happy because she thought

Earle had sacrificed himself in the belief he was saving her. To

another reporter she said, "I never touched Rheta save in love."

At

Fillmore street she was led by her captors through the crowd of

reporters and police. Dozens of cameras flashed. Her face was

impassive. She appeared weary and shaken. Her face lighted up on

seeing Earle, but fell as the haggard youth, his eyes bloodshot,

his hair disarrayed, approached her and pleaded:

"For God's

sake, mother, if you did this thing, confess. It will be better

for us all."

With a

compassionate gesture she clasped her tall son and caressed him

soothingly, Then, as Captain Stege beckoned, she straightened up

proudly and marched into the examination room.

Now her

inquisitors tried to arouse her to confession by insinuating that

Earle might be accused, but she shrewdly eyed them and remained

adamant. The morning wore on. They tried a gentler tack, Captain

Stege suggested that she might have had Rheta undress and that

perhaps she was examining her "when someone fired that shot."

She was

left in the room alone with Dr. Harry A. Hoffman, director of the

Criminal court behavior clinic. She was lying down there in the

captain's office when Captain Stege returned. He asked her if she

had had breakfast. She said she had not, and he ordered coffee.

"Captain,"

she asked, "what would happen if I told my story?"

"I don't

want any story; I want the truth," he told her.

"I will

tell it if you will shut the door," she said.

Captain

Stege described the scene later from the witness stand:

"We sat

together, the three of us, and Dr. Wynekoop put her hand on Dr.

Hoffman's knee and he put his hand on her hand. She told us that

Rheta had not been well, that she had been suffering from some

abdominal ailment. She took Rheta downstairs for an examination."

Dr.

Wynekoop said the examination became painful to Rheta and she

suggested giving chloroform to deaden the pain. The girl was

allowed to pour some on a sponge, she said, and hold it to her

nose. She talked to the girl, and after a while no response came

from her. She felt her pulse and could detect none. She vainly

applied a stethoscope to her heart. Then, indicating it was to

save her professional reputation, she shot her. That was about

4:30 p. m.

Captain

Stege asked her if it was a voluntary statement and if she would

dictate and sign it, and to both questions she replied in the

affirmative. Her strange confession, if confession it was, was

dictated in the formal, stiff language she insisted upon. The

principal part of it was:

"Rheta was

concerned about her health and frequently weighed herself, usually

stripping for that purpose. On Tuesday, Nov. 21, after luncheon,

about 1 o'clock, she decided to go down to the loop to purchase

some sheet music that she had been wanting. She was given money

for this purpose, and laid it on the table. She decided to weigh

before dressing to go downtown. I went to the office.

"She was

sitting on the table practically undressed and suggested that the

pain in her side was troubling her more than usual. She complained

of considerable soreness, also severe pain and tenderness. She

thought she would endure the examination better if she had a

little anesthetic. Chloroform was conveniently at hand and a few

drops were put on a sponge.

"She

breathed it very deeply. I asked her if I was hurting her and she

made no answer. Inspection revealed that respiration had stopped.

Artificial respiration for about twenty minutes gave no response.

Stethoscopic examination revealed no heart beat.

"Wondering

what method would ease the situation best of all, and with the

suggestion offered by the presence of a loaded revolver, further

injury being impossible, with great difficulty one cartridge was

exploded at a distance of some half dozen inches from the patient.

The gun dropped from the hand.

"The

Germans say 'the hand,' indicating the possessive case. The scene

was so overwhelming that no action was possible for a period of

several hours."

She asked

to be allowed to break the news of the confession to her children,

but she was taken back to the Racine avenue station. Later in the

day the inquest was held at the county morgue. The jury returned a

verdict that Rheta died of shock and hemorrhage from a bullet

fired in her back. They recommended that Dr. Wynekoop be held to

the grand jury on a murder charge and that her accomplices, if

any, be arrested and held on similar charges.

CHAPTER

VI.

Doctor

Collapses at Trial

ON JAN. 11

the selecting of a jury to try Dr. Wynekoop began in the Criminal

court of Judge Joseph B. David.

On Jan.

15, 1934, the state, represented by Assistant State's Attorney

Dougherty, began the presentation of its evidence. As the hearing

proceeded Dr. Wynekoop suffered five heart attacks, but the climax

came as she collapsed after Dr. Hoffman's testimony. Dr. Hoffman

had testified concerning the scene in the Fillmore street station

when Dr. Alice made the statement which she later signed.

"Did you

have any conversations with her after that?" Assistant State's

Attorney Dougherty asked.

"I asked

her why she did it," Dr. Hoffman said in a low, vibrant voice.

"Her answer was, 'I did it to save the poor dear.'"

Dr.

Wynekoop's collapse resulted in a mistrial. Less than a month

later, on Feb. 19, she again went on trial, before Judge Harry B.

Miller. She had passed her sixty-third birthday in jail on Feb. 1.

She was brought into court in a wheel chair.

Policemen

March and Kelly testified. Ahern was an important witness. Miss

Hennessey was a militant and indignant witness for the state.

Another unwilling state's witness, an old friend of Dr. Wynekoop,

was Miss Julia McCormick, elderly agent for the New York Life

Insurance company. She testified she had written a $10,000 double

indemnity policy on Rheta's life a month before her death, which

her company had change to $5,000. She conceded that in all her

negotiations with Dr. Wynekoop over the policy she had not seen

Rheta.

Two other

agents testified that Dr. Alice had approached them regarding

policies for Rheta, but that their companies declined to issue

them. Police officials took the stand, and the slain girl's father

was a tragic figure in the witness chair.

Earle did

not appear in court during the trial, but Catherine and Walker,

another son, came to their mother's aid in dramatic testimony.

The jury

required only a few minutes to determine Dr. Alice's guilt,

members later reported. They retired at 6:15 p. m. March 6, 1934,

and were agreed on the verdict at 7:15 p. m.

"We took a

vote on 25 years," said a juror. "Ten hands went up, and, with a

little urging, the other two. We had reached our verdict."

In Dwight

Dr. Alice is confined in the hospital, where it was found she was

suffering from hypertension, arteriosclerosis, and pulmonary

tuberculosis.

Source:

Gardner,

Virginia, "Wynekoop Murder!, How Woman Doctor Killed Son's Wife,"

The Chicago Daily Tribune, Chicago, Monday, 28 January 1935, p.

E9.