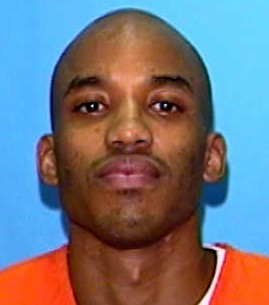

PRESSLEY ALSTON, Appellant,

vs.

STATE OF FLORIDA, Appellee.

No. 87,275

[September 10, 1998]

PER CURIAM.

We have on appeal the judgment and sentence of the

trial court imposing a death sentence upon Pressley Alston. We have

jurisdiction. Art. V, § 3(b)(1), Fla. Const. Appellant was convicted of

first-degree murder, armed robbery, and armed kidnapping. For the armed

robbery and armed kidnapping convictions, the trial court imposed

consecutive life sentences. We affirm.

The victim in this case, James Lee Coon, was last

seen January 22, 1995, while visiting his grandmother at the University

Medical Center in Jacksonville. Coon’s red Honda Civic was discovered

the next day abandoned behind a convenience store. A missing persons

report was filed shortly thereafter.

At trial, Gwenetta Faye McIntyre testified that on

January 19, 1995, appellant was living at her home when they had a

disagreement and she left town. On January 23, 1995, the day after

Coon’s disappearance, McIntyre returned to Jacksonville.

On that day, McIntyre and three of her children were

in her gray Monte Carlo parked at a convenience store when appellant and

Dee Ellison, appellant’s half-brother, drove up in a red Honda Civic.

They parked the Honda perpendicular to the Monte Carlo, blocking

McIntyre’s exit. Appellant got out of the Honda and approached McIntyre,

who reacted by driving her car forward and backward into the store and

into the Honda. Appellant took McIntyre’s keys from the ignition. He

then went back to the Honda and drove it around to the back of the

convenience store, where he abandoned it.

Appellant and Ellison then got into the Monte Carlo,

and everyone left the scene together. At that time, McIntyre asked

appellant about the Honda. He replied that it was stolen. McIntyre also

noticed that appellant was carrying her .32 caliber revolver, which she

kept at her home.

Despite their previous differences and the incident

at the convenience store, appellant continued to live with McIntyre.

Soon thereafter, McIntyre began seeing news broadcasts and reading news

reports about Coon’s disappearance and the fact that Coon drove a red

Honda Civic, which was found abandoned behind a convenience store.

McIntyre became suspicious of appellant.

When she confronted him with her suspicions, he

suggested that someone was trying to set him up. McIntyre was also

concerned because the news stories contained eyewitness accounts of the

red Honda being rammed by a gray Monte Carlo in the parking lot of the

same convenience store behind which the Honda was found. Appellant

suggested painting the Monte Carlo a different color, which appellant

did on or about February 19, 1995.

McIntyre testified that she became more suspicious

when appellant asked her how long it would take for a body to decompose

and how long it would take for a fingerprint to evaporate from a bullet.

McIntyre confided her suspicions in her minister, who eventually put her

in touch with the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office.

On May 25, 1995, McIntyre went to the sheriff’s

office to talk with several detectives, including Detectives Baxter and

Roberts. After the interview with McIntyre, police secured McIntyre’s

consent to search her home. Police retrieved, among other things,

McIntyre’s .32 caliber revolver from her home.

Based on the information that McIntyre gave to

detectives and the evidence gathered from her home, police arrested

Ellison and later on the same day arrested appellant. At the police

station, appellant was read his rights, and he signed a constitutional

rights waiver form.

After detectives told appellant that they knew about

the incident at the convenience store, that they had the murder weapon,

and that they had Ellison in custody, appellant confessed, both orally

and in writing, to his involvement in the crime.

In his written confession, appellant stated that

during the week preceding Coon's disappearance, appellant had been

depressed due to employment and relationship problems. He and Ellison

planned to commit a robbery on Saturday, January 21, 1995, but they did

not find anyone to rob.

On Sunday, January 22, 1995, they saw Coon leave the

hospital in his red Honda Civic. Appellant stated that he and Ellison

made eye contact with Coon, and Coon "pulled up to them." Appellant and

Ellison got into Coon’s car. Ellison rode in the front seat and

appellant in the back. After Coon drove a short distance, Ellison

pointed a revolver at Coon and took Coon’s watch. Appellant told Coon to

continue driving.

They rode out to Heckscher Drive and stopped. Ellison

then took Coon’s wallet, and he and appellant split the cash found

inside, which totaled between $80 and $100. As appellant searched Coon’s

car, some people came up, so appellant, Dee, and Coon drove away. They

drove to another location, where appellant and Ellison shot Coon to

death.

Following the confession, appellant agreed to show

detectives the location of Coon’s body. Appellant directed Detectives

Baxter, Roberts, and Hinson, along with uniformed police, to a remote,

densely wooded location on Cedar Point Road. Detective Baxter testified

that a continuous drive from the University Medical Center to where

Coon’s body was found, a distance of approximately twenty miles, takes

twenty-five to thirty minutes.

During the ensuing search, Detective Hinson asked

appellant what happened when appellant took Coon into the woods.

Appellant replied, "We had robbed somebody and taken him in [the] woods

and I shot him twice in the head." Because of the darkness and the

thickness of the brush, police were unable to find Coon’s body, and they

terminated the search for the remainder of that evening.

On the way back to the police station, at appellant’s

request, he was taken to his mother’s house. When Detective Baxter

mentioned that appellant was arrested regarding the Coon investigation,

appellant’s mother asked appellant, "Did you kill him?" Appellant

replied, "Yeah, momma." The detectives then took appellant back to the

police station. By then, it was 3:30 on the morning of May 26, 1995.

At that time, the detectives had to walk appellant to

the jail, which is across the street from the police station. A police

information officer alerted the media that a suspect in the Coon murder

was about to be "walked over" to the jail. During the "walk-over," which

was recorded on videotape by a television news reporter, appellant made

several inculpatory remarks in response to questions from reporters.

Later during the morning of May 26, 1995, Detectives

Baxter and Hinson, with uniformed officers, took appellant back to the

wooded area and resumed their search for Coon’s body. At this time,

appellant was again advised of his constitutional rights. Appellant

waived his rights and directed the detectives to the area that was

searched the previous day. The body was discovered within approximately

ten minutes of the group's return to the area.

The remains of Coon were skeletal. The skull was

apparently moved from the rest of the skeleton by animals. Three bullets

were recovered from the scene. One was found in the victim’s skull. One

was in the dirt where the skull would have been had it not been moved.

Another was inside the victim’s shirt near his pocket. Using dental

records, a medical expert positively identified the remains as those of

James Coon.

The expert also testified that the cause of death was

three gunshot wounds, two to the head and one to the torso. The expert

stated that he deduced there was a wound to the torso from the bullet

hole in the shirt. He explained that the absence of any flesh or soft

tissue made it impossible to prove that the bullet found inside the

shirt had penetrated the torso. The expert further testified that Coon

was likely lying on the ground when shot in the head.

A firearm expert testified that the bullets recovered

at the scene were .32 caliber, which was the same caliber as the weapon

retrieved from McIntyre’s home. This expert further testified that, in

his opinion, there was a ninety-nine percent probability that the bullet

found in the victim’s skull came from McIntyre’s revolver. However,

because the bullet found in the dirt and the bullet found inside Coon’s

shirt had been exposed for such a long period, a positive link between

those two bullets and McIntyre’s revolver was impossible.

Later during the day that Coon’s body was found,

appellant contacted Detective Baxter from the jail and asked the

detective to meet with him. Appellant did not make a written statement

at this meeting. According to Detective Baxter’s testimony, appellant

stated that he did not kill Coon but that Ellison and someone named Kurt

killed Coon.

Appellant stated that he initially placed the blame

on himself because he wanted to be "the good guy." Detective Baxter told

appellant that he did not believe him and began to leave. Appellant

asked Detective Baxter to stay and told him that he lied about Kurt

because he heard that Ellison was placing the blame on him. Appellant

then stated that he shot Coon twice in the head and that Ellison shot

him once in the body.

On June 1, 1995, appellant requested that Detectives

Baxter and Roberts come to the jail. The detectives took appellant to

the homicide interrogation room. Appellant was advised of his rights.

Appellant then signed a constitutional rights form and gave a second

written statement.

In this statement, appellant stated that Ellison and

Kurt initially kidnapped Coon during a robbery. Ellison sought out

appellant to ask him what to do with Coon, who had been placed in the

trunk of his own car. Appellant stated that when he opened the trunk,

Coon was crying and he begged, "Oh, Jesus, Oh Jesus, don’t let anything

happen, I want to finish college." Appellant said he told Ellison that "the

boy will have to be dealt with, meaning kill[ed]," because he could

identify them. Kurt left and never came back.

Thereafter, appellant and Ellison drove to Cedar

Point Road. Once all three were out of the car, appellant gave Ellison

the gun and told him, "You know what's got to be done." Ellison took the

weapon, walked Coon into the woods, and shot Coon once. Appellant stated

that he then walked into the brush and, wanting to ensure death, shot

Coon, who was lying face down on the ground. Appellant stated that

Ellison also fired another round.

Police eventually located the person appellant had

called Kurt. After interrogating Kurt, police concluded he was not

involved in Coon’s murder.

The jury convicted appellant of first-degree murder,

armed robbery, and armed kidnapping. In the penalty phase, the jury

recommended a death sentence by a vote of nine to three. The trial court

found the following aggravators: (1) the defendant was convicted of

three prior violent felonies; (2) the murder was committed during a

robbery/kidnapping and for pecuniary gain; (3) the murder was committed

for the purpose of avoiding a lawful arrest; (4) the murder was

especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel (HAC); and (5) the murder was

cold, calculated, and premeditated (CCP). The trial court did not find

any statutory mitigators.

The trial court then considered the following

nonstatutory mitigators: (1) appellant had a horribly deprived and

violent childhood; (2) appellant cooperated with law enforcement; (3)

appellant has low intelligence and mental age (little weight); (4)

appellant has a bipolar disorder (little weight); and (5) appellant has

the ability to get along with people and treat them with respect (no

weight). The trial court imposed consecutive life sentences on the armed

robbery and armed kidnapping counts and, after weighing the relevant

factors, concurred with the jury’s recommendation of death for the

murder conviction. Appellant raises seventeen issues on appeal.

Appellant’s first claim is that the trial court erred

in not granting appellant’s motion to suppress the statements appellant

gave to Detectives Baxter, Roberts, and Hinson on May 25 and 26, 1995,

on the basis that the statements were involuntary.

Specifically, appellant argues that the cumulative

effect of the following factors made his confession involuntary: (1) he

was not informed of the nature of the charges against him

contemporaneously with being taken into custody; (2) appellant did not

properly understand his rights; (3) police induced appellant’s

statements using a "Christian burial speech"; and (4) police told

appellant that if he cooperated they would speak with the judge and

state attorney.

Initially, appellant argues that his statements were

involuntary because he was not informed of the charges against him

contemporaneously with being taken into custody. We do not agree. Based

upon the circumstances of appellant’s arrest, we find that it was

reasonable for the officers who placed appellant under arrest to defer

advising appellant of the charges against him because of the officers’

concern for their own safety and because of the lack of information

concerning the case.

At the suppression hearing, Detective Baxter

testified that he asked two sergeants to arrest appellant because he,

along with Detective Roberts, was interrogating Ellison. In this

interrogation, Ellison told the detectives that he was with appellant

when appellant kidnapped Coon and then drove Coon to a deserted, wooded

area and murdered him.

Wanting to finish Ellison’s interrogation, Detective

Baxter dispatched two sergeants who were on duty at the police station

to go to appellant’s place of work, which was at a car dealership, and

arrest appellant. Detective Baxter advised the sergeants that appellant

was about to get off work and should be considered dangerous. These

sergeants knew no other details of the case at that time.

The sergeants went to the dealership, along with two

uniformed officers, and arrested appellant in the parking lot of the

dealership. Appellant was immediately taken to the police station, where

Detective Baxter read appellant his Miranda rights. Based on this

record, we find that the trial court acted within its discretion in

finding that the arresting officers acted reasonably in not advising

appellant of the charges against him at the time of his arrest.

Johnson v. State , 660 So. 2d 648, 659 (Fla. 1995).

Upon arrival at the police station, Detectives Baxter

and Roberts conducted the interrogation of appellant. Detective Baxter

had done the major part of the investigation and had taken the statement

from Ellison. Detective Baxter testified that when he first walked into

the room appellant stated that "one of the other officers said something

about a homicide." Detective Baxter testified that he told appellant to

"wait a minute" because "before he made any other statements to me, I

wanted to make sure he knew his rights." Detective Baxter then went

through the routine of advising appellant of his constitutional rights.

Appellant contends that he did not understand his

rights. After waiving his constitutional rights and while giving his

oral statement, appellant asked Detective Roberts to stop taking notes.

Appellant now argues that he was under the impression that his

statements could not be used against him if the police did not take

notes. We reject this argument. Appellant signed a constitutional rights

form which expressly provided that "[a]nything you say can be used

against you in court." Furthermore, after giving his oral statement,

appellant gave a written statement. Based upon the record, we find that

the trial court was within its discretion in determining that appellant

understood his rights. Sliney v. State , 699 So. 2d 662, 668 (Fla.

1997), cert. denied , 118 S. Ct. 1079 (1998).

Next, appellant argues that his statements were not

voluntary because the statements were induced by a "Christian burial

speech." Appellant further asserts that the confession was induced by

improper promises. Detective Baxter testified at the suppression hearing:

A. I related to Pressley Alston that Ms. Coon

obviously needed closure in this case. Again, my viewpoint or

perspective at that time was trying to get him to show us where

the body was, and this was after I told him I didn’t really care

whether he confessed, just take me to the body. I felt Mrs. Coon

needed closure because her son was still missing, and I

expressed the things about his daughter. I said, "You have a

daughter. The fact if somebody has taken your daughter and you

don’t see her again, you don’t get any closure, so I think so

it’s important from Mrs. Coon’s aspect if you can take us to his

body, that would give her some closure in her son’s death."

Q. But you didn’t promise him anything in

taking you to the body?

A. Certainly not.

Q. You were appealing to his conscience when

you made these statements about Ms. Coon?

A. I wasn’t appealing to nothing, I was just

trying to be truthful with him.

Q. Did you tell him Ms. Coon would appreciate

it if he took you to his body?

A. No, I just told him -- I just spoke of

closure. Again, I’m not speaking for [the prosecutor], and I’m

not speaking for Ms. Coon.

Appellant also testified at the suppression hearing.

He stated that when he refused to talk with the detectives, they told

him that he would find himself on death row unless he cooperated.

Appellant further testified that Detective Baxter told him that they did

not need his confession because they had Ellison’s signed confession and

McIntyre was also prepared to testify against him. Appellant stated that

in exchange for his divulging the location of the body, Detective Baxter

promised that both he and Ms. Coon would testify on appellant's behalf

at trial and that the State would be lenient. In accord with our

decisions in respect to a similar contention in Hudson v. State ,

538 So. 2d 829, 830 (Fla. 1989), and Roman v. State , 475 So. 2d

1228, 1232 (Fla. 1985), we do not find Detective Baxter’s statement that

appellant should show them where the body was located because Ms. Coon

needed closure was sufficient to make an otherwise voluntary statement

inadmissible. Nor do we find that the trial court abused its discretion

in finding that appellant’s statements were not induced by improper

police promises. In Escobar v. State , 699 So. 2d 988, 993-94 (Fla.

1997), we stated:

A trial court’s ruling on a motion to

suppress is presumptively correct. When evidence adequately

supports two conflicting theories, our duty is to review the

record in the light most favorable to the prevailing theory. The

fact that the evidence is conflicting does not in itself show

that the State failed to meet its burden of showing by a

preponderance of the evidence that the confession was freely and

voluntarily given and that the rights of the accused were

knowingly and intelligently waived.

Id. (citations omitted). Applying these

principles here, we find no error in the trial court’s ruling that

appellant’s statements were freely and voluntarily given to police after

appellant knowingly and intelligently waived his Miranda rights.

Appellant’s second claim is that the trial court

erred in denying appellant’s pretrial motion to exclude the videotape of

the "walk-over" from the police station to the jail on the morning of

May 26, 1995. The audio portion of the tape provided in relevant part:

Reporter: Did you do it? Did you know who he

was?

[Appellant]: Huh?

Reporter: Did you know who Mr. Coon was?

[Appellant]: No, I didn’t know who he was.

Reporter: They got the wrong guy?

[Appellant]: They got the right one.

Reporter: So you did it? Did you admit to it?

[Appellant]: Naw, I ain’t admit to it, but

under the circumstances –

Reporter: What -- what kind of circumstances,

pal? Why’d you do it?

[Appellant]: He was just a victim of

circumstance.

Reporter: Just somebody you came across?

[Appellant]: Just a victim of circumstance.

Reporter: And that’s it, huh?

[Appellant]: That’s it.

Reporter: Got any remorse, any regrets?

[Appellant]: I got a whole lot.

Reporter: Got a whole lot of what?

[Appellant]: Regrets, remorse.

Reporter: Doesn’t help him out now, does it?

[Appellant]: Naw, It ain't gonna help me

either. It ain't gonna help me either when I get to death row.

Reporter: What'd you like to say to his

mother, his family?

[Appellant]: I can't say that I'm sorry. I

can't say that. Um, I really can't say nothing, 'cause I don't

know what they would accept.

Reporter: You can't what?

[Appellant]: I really can't say anything,

'cause I don't know what they would accept. They probably

wouldn't wanta hear a man -- anything from a man like me.

Want me to smile?

Reporter: You think it's funny?

[Appellant]: Naw. Naw, I don't think it's

funny.

Appellant argued that the videotape was irrelevant or,

in the alternative, that the unfair prejudice to appellant substantially

outweighed any probative value of the evidence. Appellant also argued

that the videotape misrepresented him because it distorted his

appearance and attitude. In denying the motion to suppress the videotape,

the trial court found:

The Court has balanced the interests under

403, because that really is the gravamen of the motion. The

court finds that the evidence is compelling and highly probative

of the issues in this case. Indeed, the conduct of the defendant

at the time that he talked to the reporters indicates

consciousness of guilt, and the prejudicial effect does not

outweigh the probative value under the balancing test under 403.

A trial judge’s ruling on the admissibility of

evidence will not be disturbed absent an abuse of discretion. Kearse

v. State , 662 So. 2d 677, 684 (Fla. 1995); Blanco v. State ,

452 So. 2d 520, 523 (Fla. 1984). We agree with the trial court that the

substance of what was said on the videotape concerned the crime for

which appellant was charged and tended to prove a material fact; thus it

was relevant evidence as defined by section 90.401, Florida Statutes

(1995). In respect to the objection based upon section 90.403, Florida

Statutes (1995), Williamson v. State , 681 So. 2d 688, 696 (Fla.

1996), cert. denied , 117 S. Ct. 1561 (1997), is applicable. In

Williamson , we recognized that proper application of section

90.403 requires a balancing test by the trial judge. Only when the

unfair prejudice substantially outweighs the probative value of the

evidence must the evidence be excluded. The trial court’s decision on

this issue conforms with our determination in Williamson , and we

find no abuse of discretion in admitting the evidence.

Appellant argues that our decision in Cave v.

State , 660 So. 2d 705 (Fla. 1995), should be applied to this case.

We do not agree. The videotape in Cave was altogether different

from the videotape in this case. In Cave , the videotape was a

video reenactment of portions of the crime which was introduced in a

penalty-phase only proceeding. We concluded in Cave that the

reenactment video was irrelevant, cumulative, and unduly prejudicial. In

contrast, the video in this case was not a reenactment and was relevant

to the issue of appellant’s guilt, and the trial court properly

performed the balancing test pursuant to section 90.403, Florida Statute

(1995).

In his third issue, appellant alleges that the trial

court erred in denying a defense request to inform the jury that he was

taking psychotropic medication. Prior to trial, defense counsel filed a

motion pursuant to Florida Rule of Criminal Procedure 3.210 suggesting

that appellant was incompetent to proceed to trial.

The motion alleged that appellant was exhibiting

inappropriate behavior; that appellant was extremely depressed; and that

appellant was not understanding his own counsel’s advice, in that

appellant continued to believe that the police were his friends. Based

upon these allegations, the trial court ordered appellant to be examined

by two medical mental health experts. The report of the experts declared

that appellant was competent to proceed to trial. Based on this report,

the trial court adjudicated appellant competent to proceed to trial.

Later, defense counsel filed a motion pursuant to

Florida Rule of Criminal Procedure 3.215(c) requesting that the trial

judge give the jury at the beginning of the trial the following

instruction:

[Appellant] is being administered

psychotropic medication under medical supervision for a mental

or emotional condition. Psychotropic medication is any drug or

compound affecting the mind, behavior, intellectual functions,

perception, moods, or emotion and includes anti-psychotic, anti-depressant,

anti-manic, and anti-anxiety drugs.

At the pretrial hearing on the motion, the trial

court stated that rule 3.215(c) is triggered only when there is a prior

adjudication of incompetency or restoration, or when a defendant

exhibits inappropriate behavior and it is shown that the inappropriate

behavior is a result of the psychotropic medication. The court then

deferred ruling on the motion to see what type of behavior appellant

exhibited at trial.

At trial, following an outburst by appellant outside

the presence of the jury, defense counsel renewed the motion for the

abovementioned instruction. The court denied the request, noting:

I have kept an eye on Mr. Alston throughout

the proceedings, I have not seen any bizarre or inappropriate

behavior. I’m looking for it, as I indicated earlier, and he’s

just showing the normal range of reactions of a person accused

of a crime, and your request is denied.

Appellant claims this ruling was reversible,

fundamental error and cites to Florida Rule of Criminal Procedure

3.215(c)(2) and Rosales v. State , 547 So. 2d 221 (Fla. 3d DCA

1989), for support. Rule 3.215(c)(2) provides:

(c) Psychotropic Medication. A

defendant who, because of psychotropic medication, is able to

understand the proceedings and to assist in the defense shall

not automatically be deemed incompetent to proceed simply

because the defendant's satisfactory mental condition is

dependent on such medication, nor shall the defendant be

prohibited from proceeding solely because the defendant is being

administered medication under medical supervision for a mental

or emotional condition.

. . . .

(2) If the defendant proceeds to trial with

the aid of medication for a mental or emotional condition, on

the motion of defense counsel, the jury shall, at the beginning

of the trial and in the charge to the jury, be given explanatory

instructions regarding such medication.

We agree with the trial court’s decision concerning

the application of rule 3.215(c)(2). The plain language of this rule

requires an instruction on psychotropic medication only when the

defendant’s ability to proceed to trial is because of such medication.

Appellant’s motion requesting the medication instruction did not allege

that appellant was able to proceed to trial because of the psychotropic

medication. Nor was there any such evidence before the court in the

competency proceeding.

The motion simply asserted that appellant was on

psychotropic medication. This assertion alone was insufficient to

require an instruction on psychotropic medication. Accordingly, under

these circumstances, we find no error in the refusal to give the

requested instruction.

This case is distinguishable from the case before the

Third District in Rosales , upon which appellant relies. Rosales

spent seventeen years in and out of mental hospitals with the last three

hospitalizations taking place within one year of the crime for which

Rosales was charged.

On at least two occasions, Rosales was adjudicated

mentally ill under the Baker Act and involuntarily committed. In

addition, several doctors testified that Rosales suffered from paranoid

schizophrenia; that Rosales did not know right from wrong at the time of

the murder; and that Rosales was insane at the time of the murder. Most

importantly, a psychiatrist testified that Rosales was competent to

stand trial because of the medication.

In this case, there is no extensive history of mental

illness, and appellant was unqualifiedly adjudicated competent to

proceed to trial by two medical experts. However, even if we concluded

that the trial court erred in failing to give the requested instruction,

we would find that such error was harmless beyond any reasonable doubt

in this case, in that there is no evidence that appellant's taking the

medication had any effect adverse to appellant during the trial.

In his fourth issue, appellant alleges that the trial

court abused its discretion by allowing Dr. Floro, a qualified expert in

forensic pathology, to testify as to the identification of the victim

based upon methods of forensic odontology and upon the victim’s dental

records, which appellant argues were hearsay.

Dr. Floro testified that he was able to identify the

skeletal remains as those of Coon by comparing antemortem dental x-rays

provided by Coon’s dentist with postmortem dental x-rays. Dr. Floro

testified that his conclusion was reached in conjunction with a forensic

odontologist. Appellant claims that this testimony was inadmissible

because Dr. Floro was not a qualified expert in forensic odontology and

that the dental records themselves were inadmissible hearsay. We do not

agree.

We find that the trial court did not abuse its

discretion in allowing Dr. Floro to express his opinion as to the

identification of the body and that Dr. Floro’s reliance on Coon’s

antemortem dental records was permissible under section 90.704, Florida

Statutes (1995). Moreover, even if we concluded that the admission of

this testimony was error, we would find the error harmless beyond a

reasonable doubt because other evidence adequately established the

identity of the remains as those of Coon

In his fifth issue, appellant argues that the trial

court should have granted his motion for acquittal as to the armed

robbery count because there was insufficient evidence to sustain his

conviction. A judgment of conviction comes to us with a presumption of

correctness. Terry v. State , 668 So. 2d 954, 964 (Fla. 1996).

The State presented appellant’s written confession in

which appellant stated that he and Ellison stopped Coon with the intent

to rob him. Appellant also stated that he and Ellison took Coon’s wallet

while Coon was being held at gunpoint. The two then split the $80 to

$100 contained inside. Competent, substantial evidence supports the

trial court’s ruling on this motion. We find no error.

In his sixth issue, appellant alleges that the trial

court erred in failing to give an independent act instruction. Appellant

argues that there was sufficient evidence to support his theory that

Ellison was the primary planner and perpetrator of Coon’s murder, and

therefore appellant was entitled to the following special instruction:

If you find that the killing was committed by

a person other than the defendant and that it was an independent

act of the other person, not part of the scheme or design of a

joint felony, and not done in furtherance of a joint felony, but

falling outside of, and foreign to, the common design or the

original collaboration, then you should find the defendant not

guilty of felony murder.

At the charge conference, the trial judge denied the

request for the special instruction finding that it was "argumentative

and [that] it’s covered by the standard jury instructions." We find that,

on this record, the trial court did not abuse its discretion in denying

this request. See Hamilton v. State , 703 So. 2d 1038 (Fla.

1997); Bryant v. State , 412 So. 2d 347 (Fla. 1982).

While not raised by appellant, we find that the

record contains competent, substantial evidence to support the first-degree

murder conviction, and we affirm the conviction. See Williams v.

State , 707 So. 2d 683 (Fla. 1998); Sager v. State , 699 So.

2d 619 (Fla. 1997).

In his seventh issue, appellant alleges that the

trial court erred in denying a defense request to delay the penalty-phase

proceeding until his codefendant could be tried and sentenced. Two days

prior to the penalty phase, appellant moved to have the penalty phase

delayed until his codefendant, Ellison, could be tried and sentenced.

Appellant argued that Ellison could provide substantial evidence

relevant to appellant’s penalty-phase proceedings.

We rejected a similar argument in Bush v. State

, 682 So. 2d 85 (Fla.), cert. denied , 117 S. Ct. 355 (1996).

Bush was convicted of first-degree murder and was under a death warrant.

In a postconviction motion, Bush argued that his execution should be

stayed because his codefendant’s sentence had been set aside and his

resentencing was scheduled for a date after Bush’s date of execution.

Bush argued that new information could emerge from his codefendant’s

resentencing which would make a death sentence for Bush disproportional.

We rejected that contention, noting the abundance of evidence in the

record showing that Bush played a predominant role in the crime.

Similarly, the record here clearly demonstrates that

appellant played a dominant role in Coon’s murder. There is no reason to

believe, given the fact that Ellison told police that it was appellant

who shot Coon, that Ellison would have testified favorably to appellant.

Based on this record, we find that the trial court did not abuse its

discretion in denying appellant’s motion for a continuance.

In his eighth issue, appellant contends that the

trial court improperly instructed the jury during the guilt and penalty

phases as to the relative roles of judge and jury in determining what

appellant’s sentence would be should the jury return a verdict of guilty

on the first-degree murder charge. This claim has no merit.

At the close of the guilt phase, the trial court

instructed the jury from the standard criminal jury instructions. At the

close of the penalty phase, the trial court gave the jury an instruction

partially requested by appellant. Appellant argues that both jury

instructions misled the jury as to the roles of the judge and jury in

determining the appropriateness of a defendant’s death sentence in

violation of Caldwell v. Mississippi , 472 U.S. 320 (1985).

We find no error in the instruction given at the

conclusion of the guilt phase because the instructions given adequately

stated the law. See Archer v. State , 673 So. 2d 17, 21 (Fla.

1996) ("Florida’s standard jury instructions fully advise the jury of

the importance of its role."). Likewise, we find no error in the

instruction that the trial court gave at the conclusion of the penalty

phase because it too was an accurate statement of the law.

In his ninth issue, appellant alleges that the trial

court erred in permitting victim-impact evidence to be presented to the

jury. Specifically, appellant claims that the testimony of Sharon Coon,

the victim’s mother, exceeded the scope of testimony allowed under

Payne v. Tennessee , 501 U.S. 808 (1991), and section 921.141(7),

Florida Statutes (1995). We do not agree. We upheld similar testimony in

Bonifay v. State , 680 So. 2d 413 (Fla. 1996). In any event,

given the strong case in aggravation and the relatively weak case for

mitigation, we find that the claimed error, if determined to be error,

is harmless beyond a reasonable doubt. Windom v. State , 656 So.

2d 432, 438 (Fla. 1995).

In his tenth issue, appellant claims that the trial

court’s jury instruction on victim-impact evidence was erroneous. At the

close of the penalty phase, the trial court issued the following

instruction regarding victim impact evidence: "[Y]ou shall not consider

the victim impact evidence as an aggravating circumstance, but the

victim impact evidence may be considered by you in making your decision

in this matter." We find that this instruction comports with Windom

and Bonifay .

In his eleventh issue, appellant alleges that the

trial court erred in permitting the State to exhibit a full-color,

eleven-inch by fifteen-inch graduation photograph of the victim during

its penalty phase closing argument. As in Branch v. State 685 So.

2d 1250 (Fla. 1996), cert. denied , 117 S. Ct. 1709 (1997), we

find no error in the use of the photograph.

In his issues twelve, thirteen, and fifteen,

appellant alleges that the trial court erred in finding three of the

five aggravators used to support his sentence of death. When reviewing

aggravating factors on appeal, we recently reiterated the standard of

review:

[I]t is not this Court's function to reweigh

the evidence to determine whether the State proved each

aggravating circumstance beyond a reasonable doubt--that is the

trial court's job. Rather, our task on appeal is to review the

record to determine whether the trial court applied the right

rule of law for each aggravating circumstance and, if so,

whether competent substantial evidence supports its finding.

Willacy v. State , 696 So. 2d 693, 695 (Fla.)

(footnote omitted), cert. denied , 118 S. Ct. 419 (1997).

First, appellant alleges that the trial court erred

in finding that the murder was committed to avoid arrest. We disagree.

To establish this aggravating factor where the victim is not a law

enforcement officer, the State must show that the sole or dominant

motive for the murder was the elimination of the witness. Sliney

, 699 So. 2d at 671; Preston v. State , 607 So. 2d 404, 409 (Fla.

1992). Regarding this aggravator, the trial court found the following:

The aggravating circumstance specified in

Florida Statute 921.141(5)(e) was established beyond a

reasonable doubt in that the capital felony was committed for

the purpose of avoiding or preventing a lawful arrest. The

defendant and his accomplice took James Coon from a hospital

where he had been visiting an ill relative, drove him to a part

of town after taking personal property from him, and thereafter

executed him because the defendant realized that James Coon

could identify him and his accomplice. The purpose of the

killing was to eliminate a witness to the kidnapping and robbery.

This statutory aggravating circumstance was established beyond a

reasonable doubt.

We find that the trial court applied the correct rule

of law and that its factual findings regarding this aggravator are

supported by competent, substantial evidence.

Appellant also challenges the trial court’s finding

of HAC. The trial court found as follows:

The aggravating circumstance specified by

Florida Statute Section 921.141(5)(h) was established beyond a

reasonable doubt in that the capital felony was especially

heinous, atrocious, or cruel. This was not a "routine" robbery

wherein the decedent was killed simultaneously with the robbery.

James Coon was forced into his own vehicle, spent more than

thirty (30) minutes inside the vehicle with his two (2)

assailants, repeatedly begged for his life, was taken out of the

vehicle in a remote location in Jacksonville, and vividly

contemplated his death for a minimum of thirty (30) minutes. The

words of James Coon are haunting, "Jesus, Jesus, please let me

live so I can finish college." The defendant’s accomplice shot

the decedent once, and it appears that this shot was not fatal.

After the accomplice came back to the defendant who did not go

out into the woods initially with the accomplice and the

decedent, the defendant inquired as to whether James Coon was

dead. The accomplice responded that he assumed that he was as he

had shot him once.

Not content with this assurance from the

accomplice, the defendant took the firearm from the accomplice

and went to the victim who was alive, moaning, and James Coon

held up his hand as if to fend off further attacks. The

defendant then shot James Coon at least two (2) times, and there

is no question that James Coon was then rendered dead. It is

difficult for the court to imagine a more heinous, atrocious, or

cruel manner of inflicting death upon an innocent citizen who

just happened to be in the path of this defendant who was then a

predator looking for money or other things of value.

Execution-style murders are not HAC unless the state

presents evidence to show some physical or mental torture of the victim.

Hartley v. State , 686 So. 2d 1316 (Fla. 1996), cert. denied

, 118 S. Ct. 86 (1997); Ferrell v. State , 686 So. 2d 1324 (Fla.

1996), cert. denied , 117 S. Ct. 1443 (1997). Regarding mental

torture, this Court, in Preston v. State , 607 So. 2d 404 (Fla.

1992), upheld the HAC aggravator where the defendant "forced the victim

to drive to a remote location, made her walk at knifepoint through a

dark field, forced her to disrobe, and then inflicted a wound certain to

be fatal." Id. at 409.

We concluded that the victim undoubtedly "suffered

great fear and terror during the events leading up to her murder." Id.

at 409-10. In this case, we find that the trial court's findings are

supported by competent, substantial evidence. Accordingly, we find no

error with the trial court’s legal conclusion that this murder was

especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel.

Next, appellant claims that the trial court erred in

finding that the State proved beyond a reasonable doubt that the murder

was CCP. The trial court’s order sets out the basis for its finding:

The aggravating circumstance specified by

Florida Statute Section 921.141(5)(i) has been established in

that the murder was committed in a cold, calculated, and

premeditated manner without any pretense of moral or legal

justification. The essential facts justifying the conclusion

that this statutory factor has been established have been

outlined in part. This was a crime of heightened calculation and

premeditation. The defendant could have stopped at kidnapping

and robbery. He could have taken the defendant’s motor vehicle

and other valuables and left James Coon to pursue his life as an

exemplary citizen of this community. Instead the defendant

confined James Coon in his own motor vehicle and forced James

Coon to contemplate his death while the defendant decided what

to do with him. Certainly the defendant had more than ample time

to reflect upon his actions, and there was absolutely no

suggestion that he was under the influence of any intoxicants or

the domination or pressure of another. Indeed it appears that

the defendant was with his brother, his accomplice, and they

were celebrating the defendant’s brother’s sixteenth (16th)

birthday. This was an outrageous crime without even a scintilla

of evidence suggesting moral or legal justification. This

statutory aggravating circumstance was established beyond a

reasonable doubt.

Specifically, appellant argues that the State failed

to prove the heightened premeditation element of CCP. In Jackson v.

State , 648 So. 2d 85, 89 (Fla. 1994) (citations omitted), we

delineated the elements of CCP:

[T]he jury must determine that the killing

was the product of cool and calm reflection and not an act

prompted by emotional frenzy, panic, or a fit of rage (cold);

and that the defendant had a careful plan or prearranged

design to commit murder before the fatal incident (calculated);

and that the defendant exhibited heightened premeditation

(premeditated); and that the defendant had no pretense of

moral or legal justification.

Based on our review of the record, we find that the

trial court did not err in finding that this murder was CCP. We have

previously found the heightened premeditation required to sustain this

aggravator where a defendant has the opportunity to leave the crime

scene and not commit the murder but, instead, commits the murder. See

Jackson v. State , 704 So. 2d 500, 505 (Fla. 1997).

In this case, as the trial court properly pointed

out, appellant had ample opportunity to release Coon after the robbery.

Instead, after substantial reflection, appellant "acted out the plan

[he] had conceived during the extended period in which [the] events

occurred." Jackson . Accordingly, we find that the trial court

did not err in finding CCP.

In his fourteenth issue, appellant contends that the

trial court erred by giving insufficient weight to the mitigating

factors. This argument has no merit. In this case, the trial court wrote

a detailed sentencing order, and the weight to be given to the

mitigation evidence was within the trial court’s discretion. See

Bonifay , 680 So. 2d at 416; Foster v. State , 679 So. 2d 747

(Fla. 1996); Campbell v. State , 571 So. 2d 415, 419 (Fla. 1990).

To be sustained, the trial court’s final decision in the weighing

process must be supported by competent, substantial evidence in the

record. Based on this record, we find that the trial court’s decision is

supported by competent, substantial evidence.

In his sixteenth issue, appellant alleges that the

trial court erred in denying a defense motion to prohibit imposition of

the death penalty because of appellant’s mental age. Appellant presented

Dr. Risch, a clinical psychologist, who testified that because of

appellant’s borderline IQ, his mental age was between thirteen and

fifteen.

Appellant reasons that if executing a person who is

chronologically less than sixteen years old is unconstitutional,

Allen v. State , 636 So. 2d 494 (Fla. 1994), it follows that it

would be unconstitutional to execute a person whose mental age is less

than sixteen years. This claim has no merit. We have previously upheld

the constitutionality of a death sentence upon a prisoner with a mental

age of thirteen. See Remeta v. State , 522 So. 2d 825 (Fla.

1988).

Moreover, the trial court did not abuse its

discretion in rejecting this claim because the testimony regarding

appellant’s mental age was sufficiently rebutted by other evidence.

Appellant was chronologically twenty-four years old at the time he

killed Coon. Prior to trial, the trial judge ordered appellant to

undergo a competency examination.

Two mental health experts from the Department of

Psychiatry at the University of Florida Health Science Center in

Jacksonville, one of whom was a medical doctor, issued a joint report

finding that appellant had a twelfth-grade education, that appellant’s

concentration and attention span were good, that appellant read

adequately, and that appellant performed in "the average intellectual

range per [the] RAIT test."

During the penalty phase, Dr. Risch also testified

that appellant’s recognition recall and memory were normal, that

appellant’s word fluency was excellent, that appellant exhibited good

cognitive flexibility, and that there was no evidence whatsoever of

impulse control deficit or organic brain dysfunction. Appellant’s

employment supervisor testified that appellant was a "top producer" on

the job.

Finally, appellant contends that his death sentence

is disproportionate. We reject this contention. Based on our review of

the aggravating and mitigating circumstances present in this case, we

conclude that death is a proportionate penalty. See Ferrell v. State

, 686 So. 2d 1324 (Fla. 1996); Hartley v. State , 686 So. 2d

1316 (Fla. 1996); Foster v. State , 679 So. 2d 747 (Fla. 1996).

In conclusion, we affirm appellant’s first-degree

murder conviction and sentence of death. We also affirm appellant’s

armed robbery conviction. We do not disturb appellant’s armed kidnapping

conviction or appellant’s armed robbery and armed kidnapping sentences,

which appellant did not challenge.

It is so ordered.

HARDING, C.J., and OVERTON, SHAW, KOGAN and WELLS, JJ.,

concur.

ANSTEAD, J., concurs as to the conviction and concurs

in result only as to the sentence.

NOT FINAL UNTIL TIME EXPIRES TO FILE REHEARING MOTION,

AND IF FILED, DETERMINED.

An Appeal from the Circuit Court in and for Duval

County,

Aaron K. Bowden, Judge - Case Nos. 95-5326 CF and

94-5373 CF

Teresa J. Sopp, Jacksonville, Florida, for Appellant

Robert A. Butterworth, Attorney General, and Barbara

J. Yates, Assistant Attorney General, Tallahassee, Florida, for Appellee

FOOTNOTES:

1.Eyewitnesses to the incident called police. The

defense stipulated that the Honda found abandoned behind the convenience

store by police belonged to Coon.

2. Detective Baxter testified that in appellant's

oral confession, appellant stated that he handed Ellison the revolver

once inside the vehicle.

3.Neither appellant’s written statement nor Detective Baxter’s testimony

regarding appellant’s oral testimony reveals who drove from Heckscher

Drive to the location on Cedar Point Road that led into the brush where

Coon was eventually murdered. Equally unclear is Coon’s exact position

within the car from the time that they stopped on Heckscher Drive until

they arrived at the location where Coon was murdered.

4.The expert was able to make this statement based on the location of

the bullet holes in Coon’s skull. These holes were compared to where

the bullets were found, and the expert concluded that Coon must have

been lying down when shot in the head. Regarding the shot to the torso,

the expert testified that Coon was probably shot in the back because

there was a bullet hole in the back of the shirt and the bullet was

found inside the shirt near the left front pocket. The expert could not

state with reasonable medical certainty in which order the bullets were

fired.

5.§ 921.141(5)(b), Fla. Stat. (1995).

6. § 921.141(5)(d,f), Fla. Stat. (1995) (merged).

7.§ 921.141(5)(e), Fla. Stat. (1995).

8.§ 921.141(5)(h), Fla. Stat. (1995).

9.§ 921.141(5)(i), Fla. Stat. (1995).

10.Appellant’s claims are: (1) the trial court erred in not suppressing

his confession; (2) the trial court erred in admitting into evidence the

videotape of the "walk-over"; (3) the trial court erred in denying a

defense request to inform the jury that appellant was taking

psychotropic medication; (4) the trial court erred in permitting the

medical examiner to testify as to the identification of the victim based

upon methods of forensic odontology and upon hearsay records of victim’s

dental records; (5) the trial court erred in denying appellant’s motion

for judgment of acquittal as to the armed robbery count; (6) the trial

court erred in failing to give an independent act instruction during the

guilt phase of the trial; (7) the trial court erred in denying a defense

request to delay the penalty phase proceeding until a codefendant could

be tried and sentenced; (8) the trial court erred by improperly

instructing the jury as to the relative roles of judge and jury; (9) the

trial court erred in permitting victim-impact evidence to be presented

to the jury; (10) the trial court erred in giving the jury instruction

on victim-impact evidence; (11) the trial court erred in permitting a

full-color graduation photograph of the victim to be exhibited to the

jury during closing argument in the penalty phase; (12) the trial court

erred in finding that the murder was committed to avoid arrest; (13) the

trial court erred in finding that the murder was HAC; (14) the trial

court erred by giving insufficient weight to appellant’s mitigating

factors; (15) the trial court erred in finding that CCP was proven

beyond a reasonable doubt; (16) the trial court erred in denying a

defense motion to prohibit imposition of the death penalty because of

appellant’s mental age; and (17) the death sentence is disproportionate.

11.Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966).

12.Section 90.401, Florida Statutes (1995), provides: "Relevant

evidence is evidence tending to prove or disprove a material fact."

13.Section 90.403, Florida Statutes (1995), provides in pertinent part:

"Relevant evidence is inadmissible if its probative value is

substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice, confusion of

issues, misleading the jury, or needless presentation of cumulative

evidence."

14.§ 394.467, Fla. Stat. (1987).

15.Section 90.704, Florida Statutes (1995), provides: