Justice Delayed

Almost 20

years ago, the murder of an 8-year-old girl enraged Tucson; today, the

convicted killer remains alive on death row

By Chris

Limberis - TucsonWeekly.com

March 4, 2004

Vicki Lynne Hoskinson was a bright and cheery 8-year-old who had

completed her day at Homer Davis Elementary School. She pedaled her pink

bike that afternoon on what we all believed to be the safe streets of

Flowing Wells. She was heading back from dropping a birthday card into a

nearby mailbox.

Frank Jarvis Atwood was a 28-year-old pedophile, a

drifter from California who lived off his parents. He had been paroled

in May 1984 after serving prison time for a 1981 conviction; he'd been

found guilty of kidnapping an 8-year-old boy. Atwood asked the boy for

directions and then knocked down the boy's bike. He forced the boy to

fellate him.

He also had been busted in 1974 for lewd and

lascivious conduct with a 14-year-old girl and was sent to a mental

health facility.

He used his 9-year-old Datsun 280Z to get Vicki Lynne,

striking her bike with the car's bumper that bore telltale pink paint.

The bike lay on Pocito Place near Root Lane.

Vicki Lynne's sister found the bike, and her mother

rushed down the street to retrieve it. She called 911. Two teenage boys

saw the young girl in the black Z. A Homer Davis teacher also saw the

car, along with scruffy Atwood, and took down the license plate number.

Frank Jarvis Atwood returned later that day--Sept.

17, 1984--to his transient pals who were hanging out in De Anza Park on

East Speedway Boulevard at Stone Avenue. He had blood on his hands and

cactus needles on his pants. He boasted to his friends, including one

who was coincidentally struck and killed by lightning four days later,

that he stabbed a guy after a drug deal went awry. Atwood and his friend

Jack McDonald visited with another man and went to a bar to play pool.

Atwood's buddies noticed that he was spending time

sanding his knife. Atwood and McDonald left Tucson that night, taking

Interstate 10 on their way to New Orleans.

The Z broke down in Kerrville, Texas, less than an

hour from San Antonio. Atwood phoned home for help. McDonald heard this

significant part of that conversation: "Even if I did do it, you have to

help me."

The FBI had already called Atwood's parents, who told

agents that their son was getting his car fixed at Ken Stoepel Ford in

Kerrville. That's where they arrested him, searched his car and then

arranged for it to be carted to San Antonio, where it was searched again.

Ten days after Vicki Lynne Hoskinson disappeared,

Atwood was charged with kidnapping "with the intent to inflict death,

physical injury or a sexual offense on the victim." Nearly seven more

months passed before Vicki Lynne Hoskinson's remains were found.

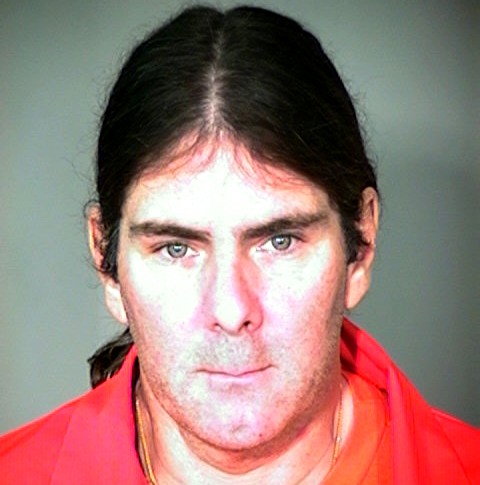

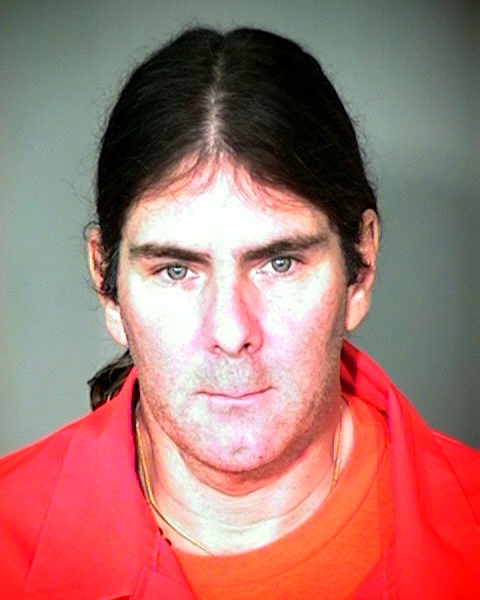

Her family's immeasurable grief, the child's sweet

face and Atwood's demonic look fanned a huge and unprecedented community

and prosecutorial response. Victim's advocates groups, as well as and

law-and-punishment organizations, sprung up with stunning force.

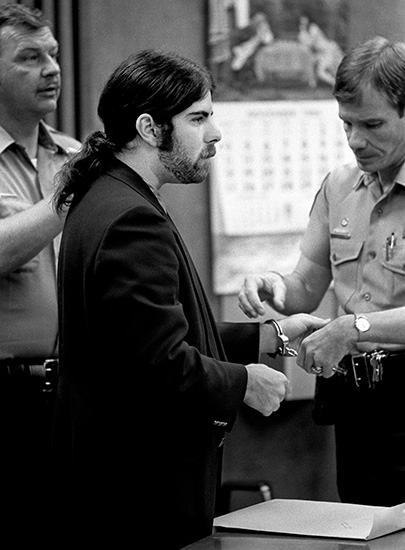

The media circus moved north to Phoenix; the trial

was moved because of the overwhelming coverage. The trial didn't begin

until January 1987. Stanton Bloom, a highly skilled defense lawyer, took

over the case for Lamar Couser and pushed every limit, both procedurally

and physically (the always-fit Bloom was so drained that he was briefly

hospitalized), against an arrogant and rule-flouting, but effective,

John Davis.

The jury convicted Atwood on March 26, 1987. He was

sentenced on May 8, and the next day, he began his now-almost 17 years

on Arizona's death row. His only travel since has been the transfer of

death row from the old Cell Block 6 at the Florence prison to the Eyman

Unit east of Florence.

That didn't stop Atwood from getting married, at age

35, on Dec. 17, 1991, to Rachel Lee Tenny, 29, of Tucson. The marriage,

witnessed by Atwood's mother, was performed inside the old prison.

Atwood has studied enough to earn a degree in

comparative religion. But he'll never rehabilitate himself in the eyes

of most Tucsonans, who are simply awaiting his execution.

Atwood has burned just one appeal, one rejected not

long after Arizona resumed executions after a 29-year hiatus brought on

by changing laws and orders from the U.S. Supreme Court.

As lucky as he was to have a talented and tenacious

fighter like Bloom, Atwood is also fortunate to have Larry Hammond

handling his new appeal. Hammond, a genial lawyer who clerked for U.S.

Supreme Court Justices Lewis Powell and Hugo Black, is committed to

justice and equality. Fresh to Arizona, he and his Phoenix law-office

colleagues joined underfunded and outmanned Rubin Salter when African

Americans filed their landmark lawsuit against the Tucson Unified School

District for its decades of official and de facto segregation.

Hammond does not have any confidence in the press

when it comes to Atwood, whom he tries to see on a weekly basis. He does

not believe there has been one thing written about the case that has

been fair to Atwood. He believes emotions were further whipped up by

photos in which Atwood's creepy looks were somehow worsened to make him

look, as Hammond says, "like Charles Manson."

Hammond teaches courses at Arizona State University's

College of Law on wrongful convictions. He says he is convinced Atwood

did not receive a fair trial. "This case has been treated as if it is

the most clear example of a horrific crime in history.

"There is tremendous hatred for Frank," says Hammond,

who declines to offer any details on the appeal.

"Why on Earth would I want to talk to the arrogant,

ignorant press?" asks Hammond, who is considerably more gracious than

the comment would indicate. He adds that he would rather run through a

path of rattlesnakes than discuss Atwood's case with a reporter.

Only 22 men, of the 126 people on Arizona's death row,

have been there longer than Atwood. It is a stark and numbingly

depressing place. And the atmosphere changed in 1992, when shortly after

midnight on April 6, Don Eugene Harding, a runty and unbalanced man, was

killed in the gas chamber. The years of warehousing were over.

Harding overpowered and killed two salesmen at the La

Quinta, now a Ramada, just off of Interstate 10 at St. Mary's Road. At

his execution, Harding flipped off Attorney General Grant Woods, then

twisted and writhed and strained. His skin turned a supernatural deep

red; his body collapsed and then rose again against the restraints. It

took 10 minutes and 31 seconds for Harding to die. Prison officials who

witnessed Harding's predecessor, Manuel Silvas, die in the gas chamber

in March 1963, told reporters that it would be over quickly, with a gasp

of air and then unconsciousness.

Harding's death was so horrific that the state

Legislature moved with rare speed to allow voters to change the method

to lethal injection.

Defense lawyers and death-penalty abolitionists

feared Harding's execution would open the floodgates. But in 12 years,

there have been only 22 executions. Nine were executed for murders

committed in Pima County. The last execution was in November 2000, and

the U.S. Supreme Court's Ring decision--putting punishment in the

hands of the jury instead of the judge--has placed a number of death

cases in limbo.

As those sentences are sent to back to juries, the

abolitionist movement is evolving. Many death-penalty opponents no

longer want to coddle or glorify the killers they seek to keep alive.

They don't instantly insist on the innocence of those in prison. And

they are not in the business of forgiving those on death row for their

heinous crimes. They have genuine sympathy and concern for the families

and loved ones of the victims.

Until that is understood, they say, the abolition

movement will lack necessary support.

Meanwhile, Hammond works on Atwood's appeal, and

those who remember Vicki Lynne Hoskinson keep waiting.