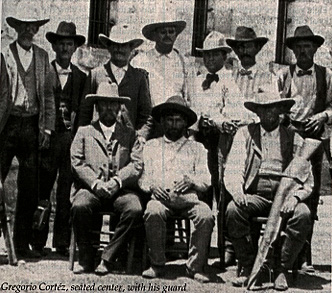

CORTEZ LIRA, GREGORIO (1875-1916).

Gregorio Cortez, who became a folk hero among Mexican

Americans in the early 1900s for evading the Texas Rangers during their

search for him on murder charges, was a tenant farmer and vaquero who

was born on June 22, 1875, near Matamoros, Tamaulipas, to Román Cortez

Garza and Rosalía Lira Cortina, transient laborers.

In 1887 his family moved to Manor, near Austin. From

1889 to 1899, he worked as a farm hand and vaquero in Karnes, Gonzales,

and nearby counties on a seasonal basis, and this transiency provided

him with a valuable knowledge of the region and terrain. Around that

time he owned two horses and a mule. He had a limited education and

spoke English.

On February 20, 1890, he married Leonor Díaz, with

whom he had four children. Leonor began divorce proceedings against

Gregorio in early 1903, alleging as part of her petition that Gregorio

had physically and verbally abused her during the early years of their

marriage and that she had remained with him only out of fear. Her

divorce was granted on March 12, 1903.

On December 23, 1904, Cortez married Estéfana Garza

of Manor while in jail. He was married again in 1916, perhaps to Ester

Martínez. According to folklorist Américo Paredes, before his encounter

with Sheriff Morris on June 12, 1901, Cortez was considered "a likeable

young man," who had not been in much legal trouble.

Historian Richard Mertz, however, interviewed

acquaintances of the Cortezes who claimed that in the 1880s Gregorio,

his father, and brothers Tomás and Romaldo were involved in horse theft,

an act Chicano historians have typically interpreted as resistance to

racial oppression. A charge of horse theft against Romaldo around 1887

was dropped due to lack of evidence, and a similar charge against Tomás

about the same time ended with an executive pardon from Governor

Lawrence S. Ross. Paredes has noted, however, that in the early 1900s

Tomás was sentenced to five years in the penitentiary for horse theft.

The event that propelled Cortez to legendary status

occurred on June 12, 1901, when he was approached by Karnes county

sheriff W. T. "Brack" Morris because Atascosa county sheriff Avant had

asked Morris to help locate a horse thief described as a "medium-sized

Mexican."

Deputies John Trimmell and Boone Choate accompanied

Morris in their search, and Choate acted as the interpreter. Choate

questioned various Kenedy residents, including Andrés Villarreal, who

informed them that he had recently acquired a mare by trading a horse to

a man named Gregorio Cortez. Morris and the deputies then approached the

Cortezes, who lived on the W. A. Thulmeyer ranch, ten miles west of

Kenedy, where Gregorio and Romaldo rented land and raised corn.

According to official testimony, Choate's poor job of

interpreting led to major misunderstanding between Cortez and Choate.

For instance, Gregorio's brother Romaldo told Gregorio, "Te quieren"

("Somebody wants you"). Choate interpreted this to mean "You are wanted,"

suggesting that Gregorio was indeed the wanted man the authorities were

seeking. Choate apparently asked Cortez if he had traded a "caballo"

("horse") to which he answered "no" because he had traded a "yegua"

("mare").

A third misinterpretation involved another response

from Cortez, who told the sheriff and deputies, "No me puede arrestar

por nada" ("You can't arrest me for nothing"), which Morris

understood as "A mi no me arresta nadie" and translated as "No

white man can arrest me." Partly as a result of these misunderstandings

Morris shot and wounded Romaldo and narrowly missed Gregorio. Gregorio

responded to the sheriff's action by shooting and killing him.

Cortez fled the scene, initially walking toward the

Gonzales-Austin vicinity, some eighty miles away. His name was soon on

the front page of every major Texas newspaper. Shortly after the

incident, the San Antonio Express lamented the fact that Cortez

had not been lynched. Meanwhile, Leonor and the children, Cortez's

mother, and his sister-in-law María were illegally held in custody while

posses mobilized to catch Cortez.

On his escape, Cortez stopped at the ranch of Martín

and Refugia Robledo on Schnabel property near Belmont. At the Robledo

home Gonzales county sheriff Glover and his posse found Cortez. Shots

were exchanged, and Glover and Schnabel were killed. Cortez escaped

again and walked nearly 100 miles to the home of Ceferino Flores, a

friend, who provided him a horse and saddle. He now headed toward

Laredo.

The hunt for "sheriff killer" Cortez intensified.

Newspaper accounts portrayed him as a "bandit" with a "gang" at his

assistance. The Express noted that Cortez "is at the head of a

well organized band of thieves and cutthroats." The Seguin Enterprise

referred to him as an "arch fiend." Governor Joseph D. Sayers and Karnes

citizens offered a $1,000 reward for his capture.

Cortez found it more difficult to evade capture

around Laredo since Tejanos typically served as lawmen in the region.

Sheriff Ortiz of Webb County and assistant city marshall Gómez of

Laredo, for instance, participated in the hunt. While anti-Cortez

sentiment grew, so did the numbers of people who sympathized with the

fugitive. Tejanos, who saw him as a hero evading the evil rinches,

also experienced retaliatory violence in Gonzales, Refugio, and Hays

counties and in and around the communities of Ottine, Belmont, Yoakum,

Runge, Beeville, San Diego, Benavides, Cotulla, and Galveston.

By the time the chase had ended at least nine persons

of Mexican descent had been killed, three wounded, and seven arrested.

Meanwhile, admiration of Cortez by Anglo-Texans also increased, and the

San Antonio Express touted his "remarkable powers of endurance

and skill in eluding pursuit." The posses searching for Cortez involved

hundreds of men, including the Texas Rangers. A train on the

International-Great Northern Railroad route to Laredo was used to bring

in new posses and fresh horses.

Cortez was finally captured when Jesús González, one

of his acquaintances, located him and led a posse to him on June 22,

1901, ten days after the encounter between Cortez and Sheriff Morris.

Some Tejanos later labeled González a traitor to his people and

ostracized him.

Once he was captured, a legal-defense campaign began

and a network of supporters developed. The Sociedad Trabajador Miguel

Hidalgo in San Antonio wrote a letter of support that appeared in

newspapers as far away as Mexico City. Pablo Cruz, the editor of El

Regidor of San Antonio, played a key role in the defense network,

which was located in Houston, Austin, and Laredo. Funds were collected

through donations, sociedades mutualistas, and benefit

performances to provide for Cortez's legal representation. B. R.

Abernathy, one of his lawyers, proved to be the most committed to

attaining justice for him.

Cortez went through numerous trials, the first of

which began in Gonzales on July 24, 1901. Eleven jurors, with the

exception of juror A. L. Sanders, found him guilty of the murder of

Schnabel. Through a compromise among the jurors, a fifty-year sentence

for second-degree murder was assessed. The defense's attempt to appeal

the case was denied. In the meantime a mob of 300 men tried to lynch

Cortez. Shortly after the verdict, Romaldo Cortez, whom Sheriff Morris

had wounded, died in the Karnes City jail.

On January 15, 1902, the Texas Court of Criminal

Appeals reversed the Gonzales verdict. The same court also reversed the

verdicts in the trials held in Karnes and Pleasanton. In April 1904 the

last trial was held in Corpus Christi. By the time Cortez began serving

life in prison for the murder of Sheriff Glover, he had been in eleven

jails in eleven counties. While in prison he worked as a barber, an

occupation that he probably pursued throughout his years of

incarceration. Cortez also enjoyed the empathy of some of his jailers,

who provided him the entire upper story of the jail as a "honeymoon

suite" when he married Estéfana Garza.

Attempts to pardon him began as soon as he entered

prison. After Cruz died, Col. Francisco A. Chapa, the politically

influential publisher of El Imparcial in San Antonio, took up the

Cortez case; he has been considered the person most responsible for his

release. Ester Martínez also petitioned Governor Oscar B. Colquitt for

his release. The Board of Pardons Advisers eventually recommended a full

pardon. Even Secretary of State F. C. Weinert of Seguin worked for

Cortez's pardon. Colquitt, who issued many pardons, gave Cortez a

conditional pardon in July 1913.

Once released, Cortez thanked those who helped him

recover his freedom. Soon after, he went to Nuevo Laredo and fought with

Victoriano Huerta in the Mexican Revolution. He married for the last

time in 1916 and died shortly afterwards of pneumonia, on February 28,

1916.

His story inspired many variants of a corrido called "El Corrido de Gregorio Cortez,"

which appeared as early as 1901. The ballad was similar to those that

depicted Juan Nepomuceno Cortina and Catarino Garza.

Américo Paredes popularized the story of Gregorio

Cortez in With His Pistol in His Hand: A Border Ballad and Its Hero,

which was published by the University of Texas Press in 1958. Between

1958 and 1965 the book sold fewer than 1,000 copies, and a Texas Ranger

angered by it threatened to shoot Paredes. In subsequent decades,

however, the book has been recognized as a classic of Texas Mexican

prose and has sold quite well. Cortez's story gained further interest

when the movie The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez was produced in

1982.

BIBLIOGRAPHY: Richard J. Mertz, "No One Can Arrest

Me: The Story of Gregorio Cortez," Journal of South Texas 1

(1974).

Cynthia E. Orozco