LIVINGSTON, Texas (AP) -- The Texas Board of

Pardons and Paroles refused to grant clemency Monday to a mentally

ill condemned killer facing execution later this week.

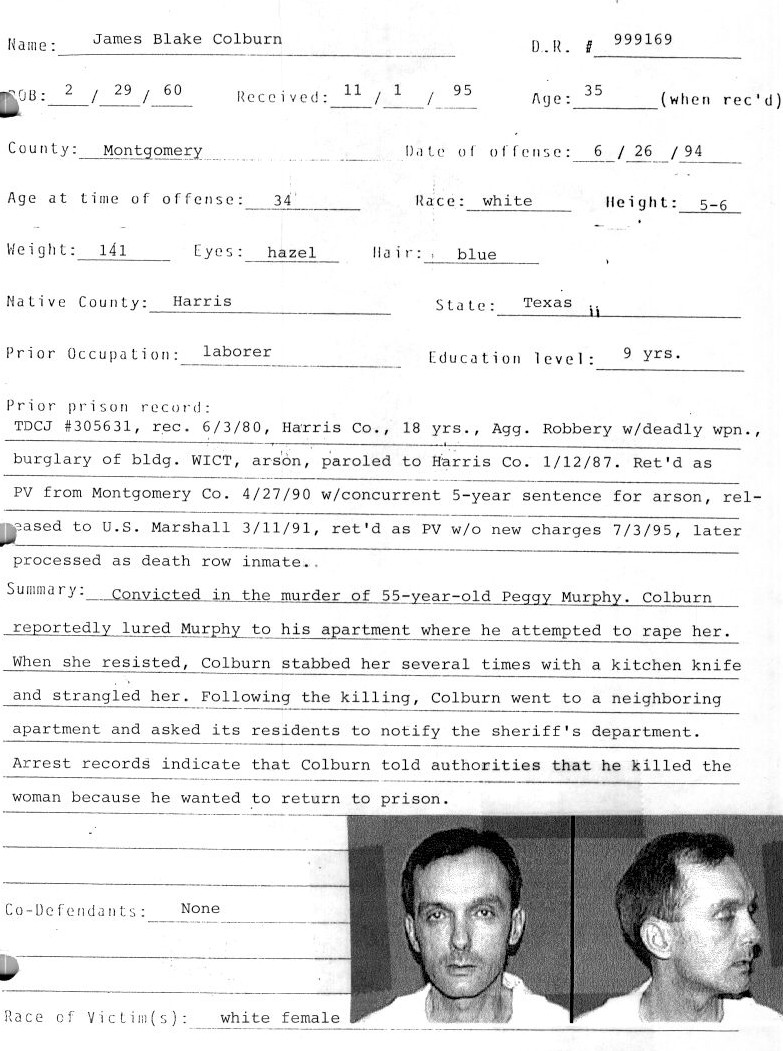

James Colburn

doesn't deny killing the 55-year-old woman as she resisted a rape

attempt at his apartment, but his lawyers contend he should be

spared because he suffers from paranoid schizophrenia. Colburn, 43,

set to die Wednesday evening, was turned down by the parole board in

a 16-1 vote with one abstention.

Colburn's lawyer, James Rytting, acknowledged

Monday that he didn't expect the panel to rule in Colburn's favor. "At

some point, we do hope when the bodies mount high enough, people's

attitudes will change," Rytting said.

Colburn won a last-minute reprieve in November

from the U.S. Supreme Court, which stopped his scheduled lethal

injection one minute before he could have been taken to the death

chamber in Huntsville. The high court in January then refused to

take up the issue of whether prisoners like Colburn are too mentally

ill to be executed, clearing the way for authorities in Texas to

reschedule Colburn's death.

The Supreme Court last year halted the execution

of the mentally retarded as unconstitutionally cruel and unusual

punishment, but the justices so far have refused blanket protection

from the death penalty for people with mental illness. Colburn,

whose criminal past includes convictions for arson and robbery, was

convicted of killing Peggy Murphy, 55, on June 26, 1994.

JAMES COLBURN

New execution date set for March 26, 2003

James Colburn won a reprieve from the U.S.

Supreme Court Wednesday night, 2 hours after he could have been put

to death, when his attorneys filed a last-minute appeal that

questioned his competency.

The appeal was received at 5:59 p.m., 1

minute before James Colburn could have been taken from his cell and

strapped to the death chamber gurney, the Texas attorney general's

office told prison officials. "The basis for the motion is we did

not get an adequate process in state court regarding Mr. Colburn's

competency to be executed," James Rytting, one of Colburn's lawyers,

said. Just after 8 p.m., the court said the execution was put off.

"It was a relief," Colburn said as he was removed

from a holding cell for the return trip to death row. "It was a

blessing from God. I was relieved for my family." "It was a surprise,"

he added.

In a brief statement, the Supreme Court said the

last-ditch appeal went to Justice Antonin Scalia, who then referred

it to the full court. The justices said the reprieve was granted

"pending the timely filing and disposition of a petition for writ of

certiorari," which is a request for the court to review the case.

The court said if the petition was denied, the reprieve granted

Wednesday evening automatically would be terminated. If the writ is

granted, the reprieve is continued until the court determines the

case. If the reprieve was lifted, under Texas law it would be at

least another 30 days before Colburn could be executed.

Once prison officials in Huntsville received word

of the court order, Colburn was taken by van to death row, at a

prison about 45 miles to the east. Even though the execution hour

was imminent, Colburn never was taken to the death chamber. "As is

our custom, we never remove the offender from the holding cell until

we get an OK from the governor's office and the attorney general's

office," Texas Department of Criminal Justice spokesman Larry

Fitzgerald said.

It was Colburn's 2nd appeal to the Supreme Court

in as many days. The justices Tuesday rejected an appeal that

contended Colburn, 42, a diagnosed paranoid schizophrenic, unfairly

could not assist his lawyers at his 1995 trial because he was so

heavily sedated. He recently said it was God's will that he be

executed. "This is what the Lord wanted," Colburn said last week

from death row, where he was sent by a Montgomery County jury for

the 1994 slaying of a woman authorities said he tried to rape at his

home. "If the Lord wanted me to live, they would have given me a

life sentence."

Mentally retarded people are protected from the

death penalty by a U.S. Supreme Court decision in June. The ruling,

however, did not extend to those determined to have mental illness.

"Executing people with severe mental illness instead of treating

them is one of the grossest violations of human rights that one

could possibly imagine," said Stephen Hawkins, executive director of

the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty. "I'm not

scared," Colburn said. "I'll get out of here. I'll be free as I know

it. I think this is, in a way, a step in the right direction for me.

If I got out, I'm scared somebody else would be hurt or killed."

In his confession to police and in recent

interviews with reporters, the former carpenter and bricklayer said

he was responsible for choking and stabbing to death Peggy Louise

Murphy, 55, on June 26, 1994.

The woman had been hitchhiking and

walked by his Conroe-area apartment. He offered her some water and

invited her inside.

When she told him she'd give him some food

stamps in exchange for a beer, he got some from a neighbor, then

attacked her in a bedroom. "It was a chance meet," Colburn said. "I

can't handle my liquor. She did nothing to upset me. I was just in a

bad state of mind. ... The devil works through alcohol, drugs. "I

knew what I was doing when I killed her. When I laid her on the bed,

something snapped." He said he choked Murphy and when she made a

gurgling sound, "I panicked and ran to the kitchen. I got a steak

knife and plunged it into her throat." When he realized she was dead,

"I turned myself in," he said.

Colburn had been in mental institutions at least

twice and was a repeat parole violator after serving a number of

prison sentences for crimes including arson and robbery. During one

prison stay, he picked up his nickname, "Shakey," after fellow

inmates noticed he suffered tremors, he said.

His criminal record was used by prosecutors to

show he would be a threat to society if not given a death sentence.

2 other condemned Texas killers, Jermarr Arnold and Monte Delk, were

executed earlier this year after similar appeals about their mental

illness failed. "The system needs to take into account a person's

mental illness when determining what charges to file and how to

prosecute," agreed Charles Ingoglia, vice president for research and

services at the Alexandria, Va.-based National Mental Health

Association. "Even though medical knowledge around mental illness

has advanced a great deal, not only has the legal profession not

kept pace, but society in general does not really understand what

mental illnesses are and aren't."

James Colburn has long struggled with delusions

brought on by paranoid schizophrenia. Many are religiously oriented,

as he revealed in a 1995 interview with a clinical psychologist in

which he said the voices he heard made it appear he was being

followed: "The voices more or less whisper it to me. They're like

illusions, coming to me from some other world, from somewhere close

to God. I'd be scared if I actually saw God. "These voices come from

somewhere around him. They're real. If they weren't, I wouldn't be

here. It's like God is trying to get across to everyone in the world

that it's all some kind of game. God's controlling my mind.

"I feel that these voices led me to find this

woman and kill her. It was wrong ... wrong in God's eyes and wrong

in everyone else's eyes. That's why I should get the lethal

injection. All these voices want me to do is get the lethal

injection. They just want to shut me up. They just want me to kill

people. "They're never going to let up until I die. They haunted me

until I did kill someone. They're not going to be happy until I'm

dead and a lot of other people are dead. I don't like talking about

these things. They just get me more and more upset.

"They tried to get me to kill someone before when

I was out on parole -- my mother and my brother and my grandparents.

They are bothering me even now. God created me. He should get rid of

me." "You are going to hear evidence that the defendant is a

paranoid schizophrenic... You will hear evidence that he's heard

voices and you are going to see him on tape. He's shaking or

fidgeting. The State is not going to contest or deny any of that..."

Prosecutor, opening statement, trial of James Colburn, October 1995.

The State of Texas intends to kill James Blake

Colburn in its execution chamber on 6 November 2002. It intends to

do so despite the fact that the 42-year-old Colburn has an extensive

history of chronic paranoid schizophrenia, a serious mental illness

whose symptoms include hallucinations and delusions.

His mental

illness is undisputed by the state. He was displaying signs of his

illness on the day of the crime, including at the time of his

confession to police. In pre-trial detention, his mental health

treatment was inadequate, resulting in several psychotic episodes.

Finally, there is evidence that he was not competent to stand trial

not least because during that period he was receiving injections of

a powerful sedative drug which apparently caused him to lose

awareness of the proceedings and even to fall asleep in open court.

James Colburn's execution would fly in the face

of repeated resolutions at the United Nations calling on the

diminishing list of countries that still retain the death penalty

not to impose it or carry it out against people with mental

disorders.

Past cases suggest that the Texas authorities care little

about such resolutions or international human rights treaties and

other standards. In which case, Texas is part of a problem that its

former governor, George W. Bush, cited in a recent address to the UN

General Assembly. Seeking a resolution on Iraq, President Bush spoke

of UN resolutions being "unilaterally subverted", and proclaimed the

US Government's desire to see a United Nations that is "effective,

and respected, and successful".

For consistency's sake, not to

mention for the sake of compassion, the President should make a

personal appeal to the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles and to his

successor in the governor's mansion in Austin, in favour of

commutation of James Colburn's death sentence.

Amnesty International members in the USA and

around the world continue to appeal to the Texas Board of Pardons

and Paroles to recommend that Governor Rick Perry commute James

Colburn's death sentence in the interest of justice and decency and

the reputation of Texas and the country as a whole (see Urgent

Action 300/02, AMR 51/157/2002, 3 October 2002).

The crime and confession

On 26 June 1994, Montgomery County police in

eastern Texas received a phone call from a neighbour of James

Colburn who said that Colburn had told him that he had just killed a

woman and that her body was in his apartment. James Colburn waited

for the police to arrive, and was arrested after the body of

55-year-old Peggy Louise Murphy was found in his home. She had been

strangled and stabbed.

At the police station, on the same day as the

murder, James Colburn gave a videotaped confession. He told the

interrogating officer that he suffered from paranoid schizophrenia.

The recording indicates that Colburn was struggling with his mental

illness. He rocked back and forth in the chair when sitting and

paced to and fro when standing. He lost control of his bladder, and

had to be provided with dry clothing. The interrogating officer

noticed that James Colburn was shaking uncontrollably.

In his confession, James Colburn said that he had

seen Peggy Murphy on the highway and had invited her into his

apartment. He stated that he had "this flash that he was going to

hurt her". He said that he tried to have sex with her, but that she

did not want it, and he abandoned his attempt. He said that "this

one impulse came over me said to kill her... I couldn't stop myself".

After the murder he said that he had considered leaving the area,

but had instead decided to go to his neighbour's home and tell him

to call the police.

The question of sanity and competency

James Blake Colburn first began displaying

symptoms of mental illness, including auditory and visual

hallucinations, in his teens and was first diagnosed as suffering

from paranoid schizophrenia at the age of 17. This was also the age

at which he was subjected to a homosexual rape by a man who had

picked him up hitchhiking.

At the time of the murder of Peggy Murphy, James

Colburn was being treated on an outpatient basis for paranoid

schizophrenia. His treatment appears to have been irregular. For

example, on 4 May 1994, eight weeks before the murder, the

psychiatrist on his case wrote in Colburn's medical records: "Off

meds? Several months. Needs to restart".

According to a post-conviction psychiatric

assessment, in the week leading up to the murder James Colburn was

allegedly experiencing increasing auditory and visual

hallucinations. He said that on the evening before the murder he

took an overdose of Valium, about 10-15 pills, in response to an

auditory command hallucination to kill himself. When he awoke the

next day, he was still experiencing auditory hallucinations.

Soon

afterwards he saw Peggy Murphy and invited her into his apartment.

According to the confession, and his subsequent psychiatric

assessments, the auditory command hallucinations continued during

the time she was in his home, and according to his recollection, led

directly to her murder.

In pre-trial custody in Montgomery County Jail,

it seems that James Colburn's mental health care was less than

adequate. Despite being an indigent defendant, the jail required

Colburn to pay for his medication from the small amount of money he

had in his commissary account. At times, this mentally ill man chose

to spend his money on soft drinks and sweets rather than on anti-psychotic

medication.

Indeed, the jail records indicate that there were gaps

in his pre-trial treatment. For example, the entry for 27 June 1994

reports that Colburn was on suicide watch. There is then no other

entry until 11 September 1994. On 19 September, the record indicates

that James Colburn "states he no longer will continue taking his

medication due to the fact that he does not want to loose [sic]

money from commissary to pay for it." On 9 October, he was treated

on an emergency basis. He was suicidal and had been urinating and

defecating on himself, and was "very agitated".

He was again placed

on suicide watch. A few days later, the records indicate that he was

again refusing medication because "he does not want to pay for it".

On 21 October, he was "very agitated and contemplating suicide". He

was placed in restraints and given anti-psychotic medication.

In November 1994, he told the doctor that he was hearing voices that

were telling him to kill himself. The doctor apparently persuaded

him to resume his medication. There are no records for the next 2

months. His condition deteriorated in mid 1995. An entry of 6 June,

for example, stated that Colburn "stated that he wants to kill

himself. He also states that he hears voices that tell him to kill

himself and that his family is dead". He was again placed in

restraints.

As part of the proceedings against him for the

murder of Peggy Murphy, the trial court appointed psychologist

Walter Quijano to evaluate James Colburn's sanity at the time of the

murder and his competency to stand trial. Dr Quijano concluded that

Colburn was "mentally ill with Schizophrenia, paranoid-type, chronic,

and should be in an inpatient psychiatric-type setting for his and

others' protection".

He concluded, however, that James Colburn was

competent to stand trial, that is, that he was able to consult with

his lawyer and had a rational as well as a factual understanding of

the proceedings against him. Dr Quijano also concluded that Colburn

was sane at the time of the crime, that is, that he knew his conduct

was wrong at the time he committed it.

The trial took place in October 1995, 10 months

after Dr Quijano's examination. No competency hearing was requested

by the defence or ordered by the court of its own accord at the time

of the trial. At the trial, Dr Quijano testified as to the

seriousness of James Colburn's illness, stating that his "paranoid

schizophrenia is what we call intractable. It is chronic. It is not

expected to disappear.

He is chronically mentally ill and the onset

is childhood and it is difficult to manage and difficult to treat."

Dr Quijano was not asked, however, nor did he offer an opinion, as

to James Colburn's present competency.

At the request of the defence attorneys, another

psychologist, Carmen Petzold, examined James Colburn in August 1995.

She concluded that "he suffers from severe chronic mental illness,

paranoid schizophrenia, depression with suicidal ideation, chronic

polysubstance abuse, most likely linked to attempts at self-medication,

and some memory deficits.

It also appeared that he may have been

suffering from a chronic Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder due to

having been raped at age seventeen, which could produce blackouts,

or periods of dissociation". She also concluded that he "appears...competent

to stand trial". She further stated that it was "likely that on or

about the time of the alleged offense, his judgment was severely

impaired, possibly due to the interactive effects of his chronic

mental illness, the presence of any drugs in his system, and his

emotionally labile state due to the suicidal ideation."

In her

opinion, "the impact of his mental illness, including the presence

of the suicidal ideation caused by living with the hallucinations,

cannot be ruled out as preventing him from conforming his behavior

to the law at the time of the crime".

A few days before the trial, the defence

attorneys contacted Dr Petzold, and informed her that she would not

be needed to testify at the trial. Defence counsel relied solely on

Dr Quijano to provide expert testimony on behalf of their client.

During the trial, James Colburn received

injections of Haldol, an anti-psychotic drug which can have a strong

sedative effect. A lay observer, a nurse with experience of mentally

ill patients, later signed an affidavit in which she stated: "I

strongly believe that James Blake Colburn was under the influence of

sedative drugs during the course of his capital murder trial. James

Blake Colburn clearly experienced temporary losses of awareness

while his trial was in progress and witnesses were testifying.

James Colburn's lapses into what appeared to be a sleep state were not

rare. The lapses were frequent in their occurrence. At intervals

approximately ten minutes to fifteen minutes apart, James would

begin to lean forward to the point that his chin rested on his chest

and James was directly facing the table top before him. James would

remain in this position until one or the other of his attorneys

prodded him awake. When James did awaken he seemed confused..." She

stated that, in her opinion, James Colburn's "lethargic condition

prevented him from participating in his defense or even paying

attention to his own murder trial".

In post-conviction affidavits, James Colburn's

trial lawyers stated that they believed that their client had been

competent to stand trial. However, they acknowledged that their

client had "dozed occasionally during the trial. On one occasion, Mr

Colburn commenced snoring loudly and we requested a recess to permit

him to wake up".

The trial record contains the following on that

particular incident: Defence lawyer 1: Judge, I don't think that it

matters, but I think I need a break to walk my client around the

room a little bit. He's snoring kind of loud. Defence lawyer 2: They

apparently injected him last night to calm him down and I appreciate

it. But he's sleeping right now. Defence lawyer 3: I don't know if

it's going to matter too much, but I think it would be better if we

had a minute to walk him around to wake him up.

The question of future dangerousness

On 10 October 1995, the jury returned a death

sentence, having determined that James Colburn would represent a

future danger to society if allowed to live. A finding of "future

dangerousness" is a prerequisite to a death sentence in Texas.

Even today, there is public fear and ignorance

around the subject of mental illness. Under the Texas capital

sentencing scheme, even if the defence attorneys put on a persuasive

case that their client's mental illness demands compassion, it may

not be enough to overcome jurors' fears of the individual in front

of them, whom they have just convicted of a violent crime.

In some

cases, legal representation of mentally ill capital defendants has

been inadequate, as has been suggested in this case. This may be due

to lack of resources or lack of experience. In other cases, a

prosecutor's bid for a death sentence may lead such officials to

play on juror fears and make a death sentence more likely under

Texas's capital sentencing scheme.

Arguing for a death sentence, the prosecutor in

James Colburn's case suggested that the jury might prevent mass

murder if they voted for execution: "To save the life of an innocent

person is a huge thing when it is compared with the taking of a

person that voluntarily chose to kill. How many lives will it save?

I submit to you, even if there's a chance it will save one, he

should be executed. But who knows, it may save one, it may save a

dozen, it may save a hundred."

Despite such exhortations, the jury evidently

wished to consider a life sentence for this mentally ill man. During

its deliberations, the jury foreman wrote a note to the trial judge

asking if the defendant would be eligible for parole if he received

a life sentence. The judge replied that the jurors were not to

concern themselves with the issue of parole.

In 1999, the foreman from the Colburn jury signed

an affidavit. In it, he stated that, in his opinion, "the lack of

information regarding when Mr Colburn could be released was a

significant factor in some jurors' decisions at the punishment phase".

This would appear to be confirmed by the affidavit of another member

of the jury who said that her "central concern was with protecting

society, and the only way I thought I could do that was to make sure

that Mr Colburn did not receive parole... [Th]e Judge's reply only

increased our frustration. We still had no idea if Mr Colburn would

be released in ten, fifteen, twenty or forty years... Consequently,

jurors continued to discuss the possibility that Mr Colburn would be

released early".

This juror said that the "primary reason" that she

had voted for a death sentence was because of her "fear that Mr

Colburn would be released early. Mr Colburn was 34 years old at

trial. Had I realized that he would not finish serving his prison

time until he was over 70 years of age, I sincerely believe that I

would have voted to give him a life sentence".

The death sentence is upheld on appeal

The appeal courts have upheld the death sentence.

This has been despite a number of affidavits and other additional

information supporting the claim that James Colburn may not have

been competent to stand trial. The power of executive clemency

exists precisely to compensate for the rigidities of the judiciary,

and are able to give full consideration to the fact of James

Colburn's undisputed mental illness. The Texas clemency authorities

should do the decent thing and recommend commutation of his death

sentence.

A forensic psychiatrist, David Axelrad, was

retained by James Colburn's appeal lawyers to review the prisoner's

medical records and examine him for the purpose of his state-level

appeals. He conducted the assessment in 1997, and undertook an

additional review in November 1999.

In a report in 1999, Dr Axelrad

stated that, in his opinion, Dr Quijano's original psychological

evaluation of James Coburn was sufficient for the purpose of

arriving at an opinion regarding the defendant's competency to stand

trial, but only at the time of his examination and report, 10 and

eight months before the trial respectively. However, Dr Axelrad

continued:

"Based upon my review of the medical records,

during the time that he was incarcerated in the Montgomery County

Jail at the time of the trial as well as my review of his records

preceding his trial raises serious questions and concerns regarding

his competency to stand trial at that time."

Dr Axelrad said that there should have been a

competency determination at the time of the trial. He also said that,

in his opinion, James Colburn was "actively psychotic" at the time

of his confession, and that he had been "seriously sedated during

the time of his trial".

He also concluded that Montgomery County

Jail had mismanaged James Colburn's treatment in pre-trial detention,

and that the jail authorities should have continued to provide him

medication when Colburn refused to pay for it himself. Finally, he

suggested that James Colburn's trial attorneys had misunderstood

their client's mental condition at the time of the trial.

In September 2000, Dr Walter Quijano signed an

affidavit in which he stated, that based on the information about

the apparent sedative effect of Colburn's Haldol injections, it was

his opinion that "during the trial itself, as opposed to the date on

which I examined him, it is not reasonably probable that Mr

Colburn.....was legally competent to stand trial".

Dr Quijano

further offered his opinion that based on the sedative evidence, "in

order to assess Mr Colburn's competency at the time of the trial, it

would have been necessary to halt proceedings temporarily and adjust

Mr Colburn's medication so that he was oriented and aware."

In the following month, Dr David Axelrad signed

an affidavit, in which he agreed with Dr Quijano on the competency

issue, stating: "it is my forensic psychiatric opinion that the

presumption that Mr Colburn was competent during trial is not

reasonable. Based on the fact that the court did not conduct a

competency hearing or inquire in any fashion into whether Colburn

was competent at the time of the trial, it is my forensic

psychiatric opinion that it is not possible to retrospectively rebut

evidence in the record indicating Mr Colburn was incompetent at

trial with any forensic scientific confidence or professional

integrity.

Based upon my review of information available to the

trial court, it is my forensic psychiatric opinion that evidence

that Mr Colburn was actually incompetent during trial is clear and

convincing."

The appeal courts have disagreed. In May 2001,

the US District Judge for the Southern District of Texas upheld the

conviction and death sentence. A year later, the US Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit rejected an appeal against the lower court's

ruling, concluding that Colburn had failed to make a "substantial

showing of the denial of a constitutional right".

On the question of

the defendant's drowsiness during the trial, the Fifth Circuit

judges said: "We need not determine the number of times Colburn fell

asleep during trial because whether Colburn fell asleep once or

slept through most of his trial is not dispositive of Colburn's

competence".

The execution date of 6 November was set by the

Montgomery County trial court. If the US Supreme Court refuses to

intervene, and clemency is denied by the Texas executive, James

Colburn will be killed on that date.

The execution of James Colburn looms at a time

when 111 countries are abolitionist in law or practice, and when the

international community has decided that the death penalty will not

be an option in international tribunals prosecuting the most serious

crimes in the world, including torture, genocide and crimes against

humanity. James Colburn's execution would be one more reminder of

how far the USA is behind much of the rest of the world on this

fundamental human rights issue.

Each year since 1997, the United Nations

Commission for Human Rights has passed a resolution which, among

other things, calls on all retentionist countries not to impose or

carry out the death penalty against anyone with any form of mental

disorder. It is clear that the execution of James Colburn would

directly contradict these resolutions.

The US grassroots advocacy

organization, the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, opposes

the use of the death penalty against people with schizophrenia and

other serious mental illness. In 1998, the organization's director

wrote of "the fundamental disconnection between law and science.

The

legal criteria for evaluating crimes committed by persons with

severe mental illnesses were developed some 200 years ago.

Conversely, medical professionals are able to accurately diagnose

schizophrenia and other serious brain disorders due to remarkable

scientific discoveries. Scientists also have established that

schizophrenia impairs mental capacity in many cases. In view of this

progress, a diagnosis of schizophrenia by a qualified medical expert

should serve as a reason not to execute a criminal defendant."

On 25 September 2002, US District Judge William

Wayne Justice made an address to psychiatrists and others at the

University of Texas-Houston Medical School. In it the District Judge,

who was appointed in 1968 and has extensive experience of the Texas

criminal justice system, stated that the Texas criminal justice

system was operating under a "spirit of vengeance" in its dealings

with the mentally ill.

He referred to the case of Andrea Yates, a

woman suffering from mental illness against whom Texas prosecutors

recently sought the death penalty for killing her children: "Andrea

Yates did a monstrous thing, but it not a monstrous human being. She

is, ultimately, a pathetic and tragic figure".

He said: "If we

reject the moral necessity to distinguish between those who

willingly do evil, and those who do dreadful acts on account of

unbalanced minds, we will do injury to these people. But the

ultimate injury is the one we will inflict on ourselves, and on the

rule of law". Texas should commute the death sentence of James

Colburn. It is time for the state to find a compassionate response

to his crime.