A Day in the Death of Inmate no. 918

November 14, 2003

HUNTSVILLE - Execution of Inmate No. 918 was

nothing if not efficient. At the stroke of midnight Tuesday, the

inmate took the last steps of his life on Earth from a holding cell

into the death chamber.

By 12:01 a.m. Wednesday, five thick tan straps

secured his legs, waist, and torso to a stainless steel gurney with

a cushion on top.

His arms were stretched wide. Intervenes tubes

were quickly inserted into each.

His head lay flat. His eyes blinked rapidly. He

stared into the microphone, suspended two feet above his mouth.

Above the microphone, was a bright fluorescent light.

At 12:03, a harmless saline solution began

flowing into his left arm and, at 12:05, into his right.

Witnesses quickly were ushered into the adjoining

room with drab brown carpet and white curtains around the walls. A

glass partition and bars separated the witnesses from inmate No.

918.

The instant the last witness was in the room, a

figure appeared from a room behind the death chamber. The figure

nodded to Warden Morris Jones, standing by the gurney. It was 12:08.

"We're ready warden," he said.

Two minutes alter, Anthony Cook, who said he had

turned his soul over to Jesus Christ, forfeited his life to the

State of Texas. In that regard, his case is not unique. Texas has

executed 70 men since 1982, more than any other state.

But Cook's case was unusual in two ways. Unlike

most condemned prisoners, he submitted to his fate by choosing not

to appeal his death sentence. And, for the first time since the

state resumed execution 11 years ago, it executed a killer whose

victim lived in Travis County.

Texas the Leader

For years, the Supreme Court has been whittling

away at efforts by capital punishment opponents to get death

sentences overturned. And for years, opponents have warned that what

had been a trickle of executions was about to become a torrent.

Cook's execution which took a total of 15 minutes

start to finish, shows how routine they have become in Texas. Indeed,

seven more executions have been scheduled over the next 31 days,

although almost all of these are likely to be stayed. Across the

nation, 38 people have been executed this year and 17 in Texas.

The first women likely to be executed by the

State of Texas -Karla Faye Tucker- had been scheduled to die early

Friday. But she received a stay last week.

Proponents of capital punishment shed no tears

for the inmates, pointing out that their executions are painless

compared with the often brutal agony their victims faced before they

died. Opponents, however, still cringe at the loss of one human's

life, no matter the circumstances.

Consent to Die

Cook's execution went quickly, even by Huntsville

standards. Indeed, his case was unusual because there was no appeal

pending, no waiting for the phone call that might signal the 11th

hour reprieve. Prison officials were ready to proceed when the clock

struck midnight, as called for in the death warrant.

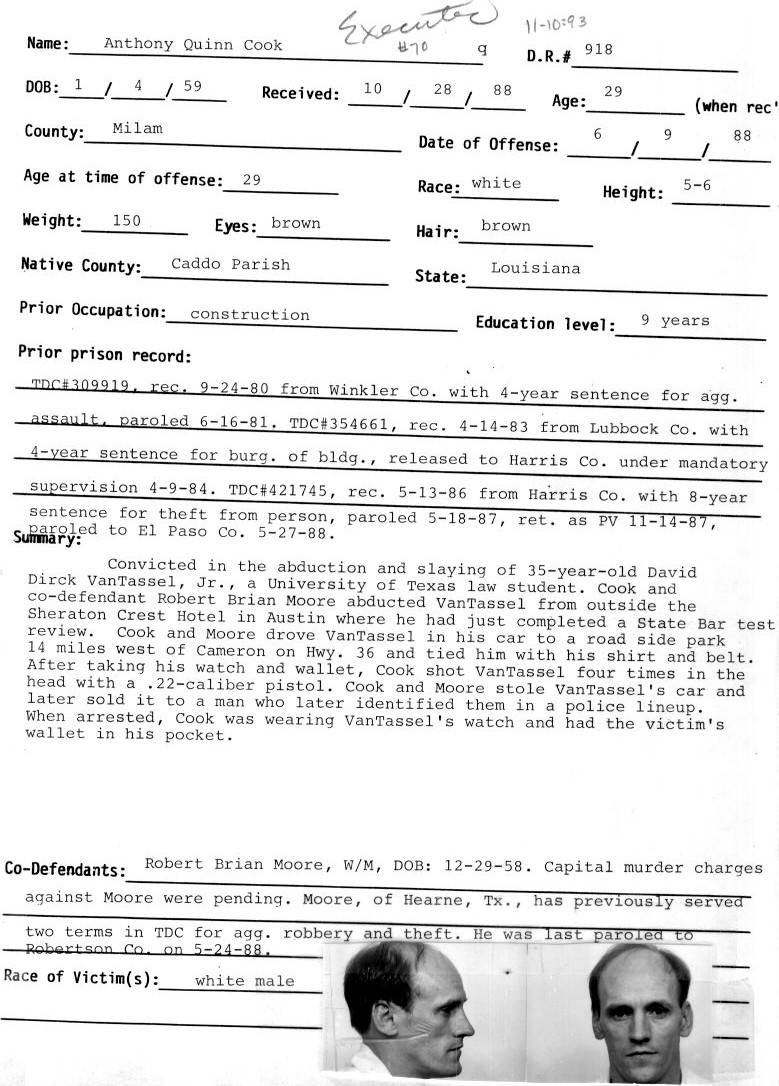

Cook was sentenced to lethal injection for the

1988 murder of David Dirck Van Tassel Jr., a University of Texas law

school graduate who was abducted from the parking lot of a downtown

hotel and driven to Milam County, where he was shot four times and

robbed of his car, wallet and watch.

At first, Cook proclaimed his innocence in the

crime, which was prosecuted in Milam County. But then he found Jesus.

Though he did not relish the thought of execution, he decided that

the Bible decreed he should die for his crime. He waived all his

appeals, except the one required by state law. Lawyers could do

nothing.

Condemned inmates spend an average of 8.4 years

on death row before execution. Cook spent five years there. He was

what death penalty opponents call "a consensual." Prison officials

could not remember a similar case since James Smith consented to

execution on June 6, 1990.

Outside the Walls Unit, Dennis Longmire stood

with one other death penalty opponent shortly before midnight. A

rolling mist chilled the university professor?s bones. What was

about to happen inside chilled his soul.

"This is an odd one to be at since the guy is

volunteering for it," said the Sam Houston State University

criminology professor. "The more (executions) we do, the easier it

becomes, I believe. It greatly concerns me."

Barbara Stetzelberger, the slain victim's widow,

waited in Austin for a phone call informing her that her husband's

killer was dead.

"I don?t have any wish for his death,"

Stezelberger said. "I feel that's a decision we've made as a society.

I think God is the only one who knows justice.

"I have a good life, but it's never the same,"

she added. "You go on and rebuild, but it's not the same. It gives

you a good idea of what people in wars go through. I think our wars

are on the streets."

"Mood Appears Calm"

Van Tassel's murder was sudden and brutal. Cook's

execution, like all others, was well planned. His last 24 hours were

documented meticulously.

By the time execution day arrives, condemned

inmates have drawn up their last will and testament. They have

specified what will be done with their bodies. They have decided

what they want, if anything, for their final meal.

Prison employees monitor condemned inmates

constantly during the final 24 hours. In 1974, the state, responding

to a U.S. Supreme Court verdict, rewrote its death penalty statues.

The very first inmate sent to death row under the new laws cheated

the executioner by killing himself on July 1 of that year.

The Cook vigil began at midnight Monday.

"Lying on bunk," read the guard's log.

At 1:15a.m., he sat up and wrote a letter. Ninety

minutes later, he sipped coffee and chatted with a guard named

O'Ginn.

Three a.m. brought an early breakfast: pancakes,

syrup, oatmeal, gravy, butter, sugar, milk and coffee. He followed

the meal with a nap. For the final 24 hours, when it comes to eating

and sleeping, normalcy is suspended.

At 8:20 a.m., Cook began saying goodbye to his

family. The visits continued on and off throughout the day, until 4

p.m. Then it was time to say goodbye to "The Row."

Condemned prisoners are moved to the Walls Unit

the day before the execution. Death row is located in the Ellis Unit,

16 miles north of Huntsville. For security reasons inmates are moved

at various times, and different routes are used. Only a few people

know the time and the route for each trip to the holding cell next

to the death chamber. Cook was picked up at 4 p.m. He was ushered

into a holding cell next to the death chamber at 4:30 p.m.

"Mood appears to be calm," the guard noted in his

log.

The Last Meal

The best-known ritual of capital punishment is

the last meal.

Most of the 70 inmates who have been executed in

Texas since 1982 requested traditional fare such as T-bone steaks or

cheeseburgers.

Some eat heartily. One inmate in 1990 asked for a

T-bone steak and four pieces of chicken (two breasts, two thighs),

fresh corn and iced tea. Another that same year wanted three

hamburgers, french fries and chocolate ice cream with nuts.

Others eat sparingly. One inmate in 1985

requested a flour tortilla and water. Another in 1991 asked for an

apple.

The requests are occasionally exotic. Last August,

Carl Kelly asked for ?wild game or whatever is on menu.? He left

uneaten the cheeseburger and french fries that the prison officials

brought.

Increasingly, as Texas picks up the pace of execution, inmates are

refusing their last meals, perhaps in protest. Of the first 25

inmates executed since 1982, only one turned down a last meal. Of

the past 17 condemned inmates, seven have refused to eat.

Occasionally, the requests are ethereal in nature:

Carlos Santana in March asked for "Justice, temperance, with mercy."

Danny Harris, executed in July, sought "God's saving grace, love,

truth, peace, freedom."

In his mind, Cook had those. He requested a

double-meat bacon cheeseburger and a strawberry shake. His meal was

delivered between 6:30 p.m. and 7 p.m. Monday. After that, he

showered, according to policy, and donned a pair of state-issued

pants, a shirt and his personal tennis shoes.

"It's so weird to come here"

An hour before midnight, reporters who would

witness the execution gathered in the office of prison spokesman

Charles Brown. Brown had just received an update form prison

officials.

"They said he's just ready to go," Brown said. "They

said he's just real calm."

The reporters represented the Austin American-Statesman,

Huntsville Item, The Associated Press, United Press International

and Harper's.

Some of the reporters present had seen dozens of

executions. One was a novice to the process. For two of them, this

was the next assignment after a Huntsville City Council meeting.

"It's so weird to come here from City Council,"

one said.

"I don't know. Some days, I'd like to see some of

them hooked up," another said. He said he had seen "somewhere over

30" executions.

The phone rang. It was almost time. The witnesses

were summoned to a visiting room less then a minute form the death

chamber.

Guards pat-searched the witnesses for contraband

- male guards for the male witnesses, female guards for the women. A

beeper was confiscated from a reporter, to be returned after the

execution.

Again, the phone. "That could be the call," one

reporter said.

"We're ready," a guard said. Another walk, this

one down a white corridor, outside through two chain link fences

into yet another building, past the holding cell that kept Cook for

seven hours and a few precious minutes.

The witnesses were whisked into a room. The

figure stepped out from the hidden room. Signaled. Stepped back in.

Warden Jones asked Inmate No. 918 if he had any

final words.

"Yessir," Cook responded. He licked his lips once

and stared at the bright fluorescent light. "I just want to tell my

family I love them and I want to thank the Lord and savior Jesus

Christ for giving me another chance and for saving me. That's it."

At 12:08 a.m., a mixture of pancuronium bromide,

which relaxes the muscles, potassium chloride, which stops the heart,

and sodium thiopental, which induces unconsciousness, began flowing

into Inmate No. 918?s veins. The average cost of the drugs is $71.50

per execution.

Inmate No. 918 gulped, blinked. His stomach moved

up and down strangely. The effect of the drugs seemed immediate.

Inmate No. 918 strained against the heavy tan straps and coughed or

chocked, as if seeking air.

At 12:10 a.m., the flow of the drugs subsided. No

one moved. The chaplain, inside the death chamber, starred at the

floor.

The witnesses watched the corpse intently, as if

expecting Inmate No. 918 to arise. The reflection of their faces

could be seen in the glass partition separating the rooms.

Finally, Warden Jones made a motion toward the

door to the death chamber. He admitted a medical doctor, who pulled

out a stethoscope. He several minutes hunched over the body,

probably, listening.

He removed his stethoscope, looked at his watch

and looked at the warden.

"I've got 12:15," he said.

"12:15," the warden repeated.

Three hundred and sixty inmates remain on Texas'

death row. More than 600 capital murder cases are pending on the

dockets of the state's six largest counties.

source: David Elliot, Austin-American

Statesman