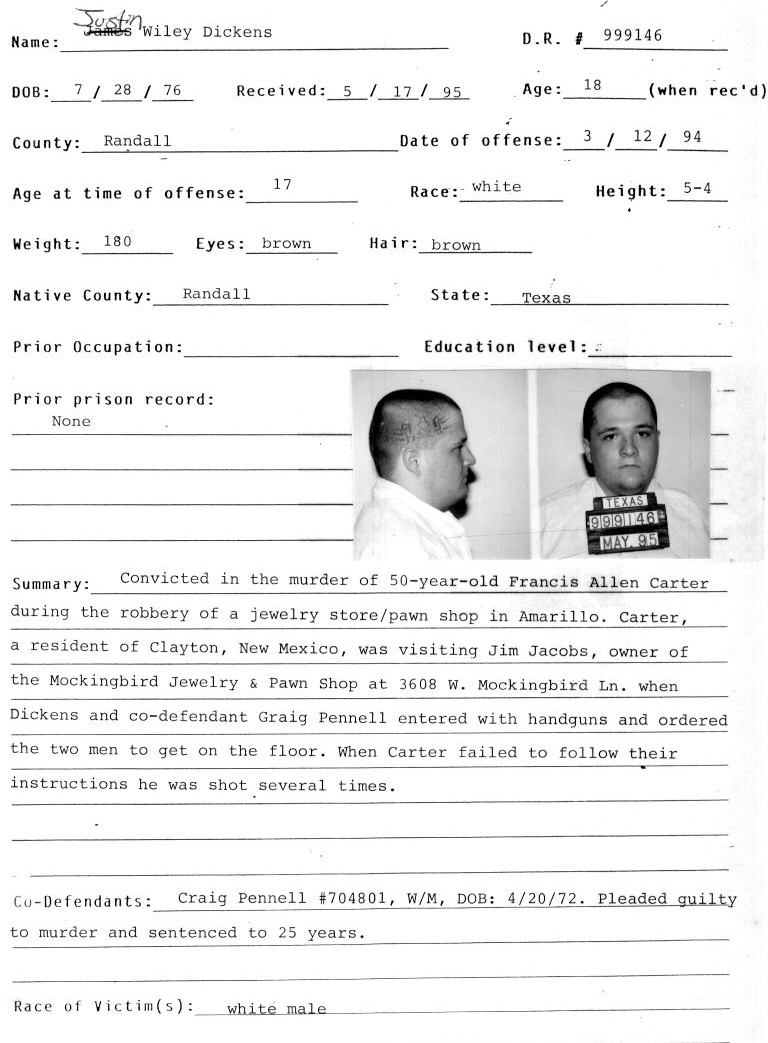

Dickens was convicted in the March 12, 1994,

murder of 50-year-old Francis Allen Carter, a schoolteacher from

Clayton, N.M. Carter was visiting with the owner of Mockingbird

Jewelry and Pawn Shop when Dickens entered to rob the store and

ordered Carter and the owner to the floor. Carter was shot twice

while the owner ran out the back door and alerted police.

"He was a drug-dealing tattoo

artist who used LSD. I just wanted to be like him," Mr. Dickens

remembered. "I was like his dog, you know. Dallas accepted me. He

accepted me."

Acceptance assumed supreme importance to a

teenager who hardly stood 5 feet tall, whose father had

disappeared and whose absentee mother nurtured her son by teaching

him to shoplift.

The dealer and the kid enjoyed some fun times,

at least until Mr. Dickens – striving to repay a debt to his

criminal mentor – shot a beloved high school teacher between the

eyes. After that, Mr. Moore was free to move on to other states

and additional felonies.

Mr. Dickens went to prison under a death

sentence.

His age at the time of the murder – 17 –

ultimately placed him among the 73 condemned men hoping for what

amounts to a mass commutation from the U.S. Supreme Court.

Today, justices will hear arguments on the

constitutionality of capital punishment for crimes committed under

the age of 18.

But for that, Mr. Dickens' 10-year-old case

would long ago have faded from attention, just another West Texas

armed robbery with a bloody and tragic ending. At best, it

provided an unnecessary lesson in the stupidity of combining drugs,

guns, fear, bad influences and deadly ineptitude.

It also bore the saddest of ironies: He killed

the man he should have met.

If only Chicken Dickens had come under the wing

of the inspirational teacher instead of the trailer-park crime

boss, there might well be one less ill-fated loser in prison today.

But that would require the sort of good fortune and youthful

application that never attached to Mr. Dickens.

He is 28 now and has spent the last third of

his life locked up. His hairline has begun to recede, revealing

the image of a hooded executioner inked on his right temple.

"I wasn't a bad person," he said in a recent

prison interview. "You may not believe that."

Many don't, including the man who prosecuted

him, Randall County District Attorney James Farren: "Justin Wiley

Dickens would kill you and your family if you were between him and

something he wanted."

Destined to offend?

Instead of inherent malevolence,

however, Mr. Dickens' defense attorney saw a pre-ordained doom.

"This kid," Amarillo lawyer Rus Bailey said, "never

stood a chance from the day he was born."

The trouble started even before that.

His mother, Vicky Raelene James, decided early

in her pregnancy that she didn't want to have a second child. "I

used methamphetamine to try to abort," she testified at his 1995

trial.

Released in June from prison for robbery, Mrs.

James initially agreed to be interviewed about her son, only to

change her mind. Later she agreed again, but changed her mind once

more.

"I don't blame her," Mr. Dickens said of his

mother's effect on his fate. "She was a good mom when she wasn't

high. But she had her own addictions."

Mainly they were heroin and cocaine. She was

arrested a dozen times or more; her children were in and out of

foster homes. When her son was 10, she tried to commit suicide by

slashing her wrists with a broken mirror.

A childhood memory from Mr. Dickens: "Me and my

mom started shooting dope [cocaine]. My mom, she would run the

streets, shoplifting from stores. She'd steal leather jackets,

watches, Monistat, anything. I was basically a decoy. I'd walk

around the store and be a distraction."

The paternal side of the family had problems as

well. Mr. Dickens' father didn't hang around long, but a

stepfather, Geary James, took over.

He could be a doting dad, trial testimony

showed, except when he was a doping deadbeat. Once, as Mr. James

sat reading a story to young Justin and his sister, members of the

Mexican Mafia dropped by to deliver a death threat related to

money owed for marijuana sales.

When he was in sixth grade, Mr. Dickens said,

"I walked in on my stepdad shooting up in the garage."

(Mr. James is currently serving a prison

sentence on drug charges. Earlier this year mother, stepfather and

son were all in prison at the same time, though in different

institutions.)

By the time he was 14, Mr. Dickens said, he was

living on his own. He got the nickname "Chicken," he said, because

of his short stature and bantam personality. He huffed gasoline

and used LSD. His theft of marijuana from a motorcycle gang earned

him a pistol-whipping.

Then he met Mr. Moore, who at age 32 was fresh

off a 10-year stretch for first-degree robbery in Missouri.

"He was like a cult figure, an icon," Mr.

Dickens recalled. "Me and Dallas became tight."

Mr. Moore gave his new protege a gratis tattoo

on his torso – a depiction of a skull wearing a derby decorated

with a swastika. When Mr. Moore married his longtime girlfriend,

they took Mr. Dickens along on the honeymoon in the bridal suite

of an Amarillo motel.

A fraternal bond

"He seemed like the big brother

I never had," Mr. Dickens said. "He was a people person."

Somewhere in all this bonding the two of them

developed a steady habit of injecting cocaine.

"That's when the bottom fell out," Mr. Dickens

said.

It fell hardest when Mr. Moore's wife and Mr.

Dickens absconded with a thousand dollars worth of Mr. Moore's

cocaine and had a private party. Mr. Moore showed his displeasure

by knocking Mr. Dickens around with the barrel of a handgun and

demanding repayment.

"He had a ski mask hanging on the wall," Mr.

Dickens said. "He pointed to it and said, 'When I get in trouble,

I handle my business with a pistol.' "

But Mr. Dickens had no pistol. So he went to

his great-grandfather's house, ate some "home-made sticky buns,"

then strode into the bedroom and secretly lifted a .357.

"The best friend I ever had in the world," he

said. "I betrayed him and stole his gun."

An acquaintance drove as he searched for a

place to rob. They had been drinking beer, taking Valium and doing

coke. Pantera's Cowboys From Hell screamed from the pickup

truck's speakers. "Here we come," the song goes, "reach for your

gun."

On Amarillo's south side, they stopped at

Mockingbird Jewelry & Pawn. Mr. Dickens walked in alone, with the

gun in a pocket of his Oakland Raiders jacket. It was 6 p.m. on

March 12, 1994.

Two men stood talking at the shop's counter –

the owner and a jewelry salesman, Allen Carter of Clayton, N.M.

Mr. Carter was a Vietnam veteran who had grown

up dirt poor. "He started working to help support his family when

he was six years old," said Mr. Farren, the district attorney.

At age 50, he dealt in jewelry only as a

sideline. His real job, and deep calling, was teaching English at

Clayton High School.

He had taught there for 23 years, sponsored the

student newspaper and was named teacher of the year in 1986. He

was the sort of teacher who once took out a personal loan to help

a promising former student pay college tuition.

"Allen was just one of those individuals – he

was like a magnet," said Clayton principal John Burgess. No one

failed Mr. Carter's class, Mr. Burgess said, because he worked

with every student – even the most troubled – as much as necessary.

"He would not accept failure."

Added colleague Barbalee Blair: "He really,

really had a way with kids. He was a fierce, nail-'em-to-the-wall

kind of guy who spoke to them in their language."

Then he encountered Mr. Dickens, a junior-high

dropout pointing a loaded Smith & Wesson.

"Get on the floor," Mr. Dickens ordered. "Do

what I tell you [or] I will kill you."

The shop owner and Mr. Carter complied. This is

Mr. Dickens' version of what happened next:

Mr. Carter rushed him and began punching him.

Mr. Dickens dropped into a fetal position against the wall. Mr.

Carter grabbed for the gun and it went off, hitting him in the

head.

The owner of the pawnshop was able to flee. He

testified that he did not get a clear view of Mr. Dickens shooting

Mr. Carter.

Prosecutor Farren said physical evidence,

including blood spatters, did not support Mr. Dickens' account. "It's

a lie," he said.

It's also an important legal distinction; if

the shooting were accidental, it would not have been capital

murder.

Clayton principal Burgess said he can well

imagine Mr. Carter trying to persuade yet another wayward youth to

turn his life around. "He would try to talk him out of it," Mr.

Burgess said. "But he would not try to physically overtake him.

That would be out of character."

When news of his brutal death reached Clayton,

the students couldn't believe it. "The kids were crushed," Ms.

Blair said. "We've had other bad things. But I've never seen them

like this."

Back in Amarillo, a friend testified, Mr.

Dickens bragged about what he had done. "He thought it was like

kind of funny, I guess," she said.

Mr. Dickens has this explanation: "I just felt

an incredible sense of shame, and the only way to play it off was

act like Mr. Bigshot."

The prosecutor had another interpretation: "He

wasn't 'Little Chicken' anymore. He was finally a gangster."

When one of Mr. Dickens' friends turned him in,

Mr. Moore, as a veteran of criminal justice problems, had some

advice. "He said: 'Take it easy. You're young; you'll be out in 15

years,'" Mr. Dickens recalled. "He said, 'They can't touch you.' "

A decade later, a new generation at Clayton

High School walks past an oak tree planted in Mr. Carter's memory.

"The kind of kid who killed him," principal Burgess said, "would

be the kind of kid that Allen Carter would save."

'Shame and sorrow'

From death row, Mr. Dickens

watches as his appeals are slowly exhausted. The most recent

denial, in June, came from the federal court in Amarillo. And he

was recently diagnosed, he said, with Hepatitis C – not an

unlikely occurrence after years of needle drug abuse.

He said he is sorry about Mr. Carter's death

but does not believe he deserves lethal injection.

"I feel a lot of shame and sorrow. It haunts me

to know that I killed a man," he said. "I know in my heart I'm not

a cold-blooded murderer. There are many people who share the blame."

One of those, in Mr. Dickens' mind, is Mr.

Moore.

After the murder, Mr. Moore moved to New Mexico,

where he turned over a new leaf by committing burglary, kidnapping

and jail escape. Now on parole, he gave only a brief interview

about the teenager who idolized him.

"He was just a young kid, trying to step up to

the plate and trying to impress people," Mr. Moore said. "He got

caught."

Such a response doesn't surprise Mr. Dickens. "Looking

back, I know he never had no love for me."

But even facing execution, Mr. Dickens can't

quite abandon all affection for the one who took him in, no matter

how badly it all turned out.

"I still love him," he said. "And I still hate

him."