Supreme Court of Ohio

State v. Dunlap (1995), Ohio St.3d .

No. 94-1777

The State of Ohio, Appellee, v. Dunlap, Appellant.

Submitted June 6, 1995

Decided August 23, 1995

Appeal from the Court of Appeals for Hamilton County,

No. C-930121.

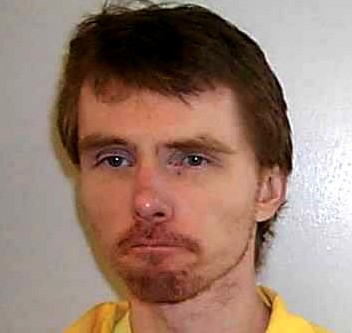

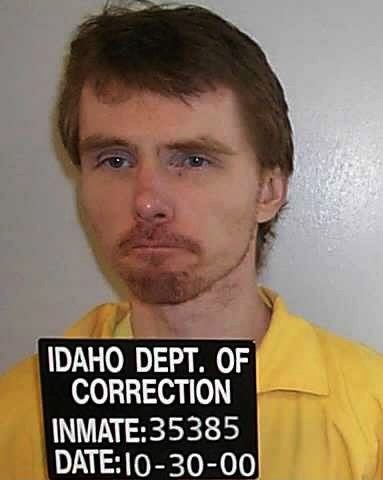

On October 6, 1991, at a Cincinnati park, defendant-appellant

Timothy Dunlap used a crossbow to shoot two arrows into his girlfriend,

Belinda Bolanos. After Dunlap left Bolanos to die, he drove her Chevette

across the country until he arrived on October 16 at Soda Springs, Idaho.

There, Dunlap used a sawed-off shotgun to rob a bank and kill bank

teller Tonya Crane. Idaho police captured him that afternoon. Dunlap now

appeals his Ohio conviction and death sentence for the aggravated murder

and robbery of Bolanos.

In June 1991, Dunlap traveled from Indiana to

Cincinnati, where he found casual labor jobs and lived on the streets

and in inexpensive motels. That summer, he met Bolanos in Cincinnati,

where he worked as a temporary worker. They began dating, traveled to

Florida, and in mid-September started living together in her early 1980s

Chevette hatchback. In late September, Dunlap bought a crossbow and

thought about killing Bolanos.

On Sunday morning, October 6, 1991, Dunlap asked

Bolanos to go with him for a picnic near the Ohio River. When they

arrived at a river park, Dunlap told her he had a surprise for her.

Dunlap described later how he "blind folded her, walked her into the

woods, had the cross bow with me, shot her once in the neck, she fell to

the ground, then I shot her once in the head." He shot her in the neck

so "she wouldn't be able to scream." In the head, he chose "the closest

place to the temple, softest part of the skull." Dunlap killed her to "get

her car, credit card and checks." When he left her, he drove her

Chevette to Louisville, Kentucky.

In Louisville, Dunlap purchased a 12-gauge shotgun

and then drove for several days through Kentucky, Missouri, Arkansas,

Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and Idaho until he arrived at

Soda Springs, Idaho. Along the way, he sawed several inches off the

shotgun barrel. During his journey, he assumed the fictitious name of

Steve Bolanos and used Belinda's credit card to pay for gas, meals and

lodging.

On October 12, while Dunlap was driving across the

country, Bolanos's body was discovered in the woods. The coroner found

that Bolanos died as a result of wounds caused by two arrows: one arrow

went through her throat almost five inches, and the other arrow, shot

into the right side of her head, pierced her brain for six inches.

Despite these injuries, Bolanos probably lived for fifteen to thirty

minutes after she was shot.

Around 9:30 a.m., October 16, Dunlap walked into a

Soda Springs, Idaho bank with the sawed-off shotgun and asked teller

Crane for all of her money. According to one teller, Dunlap shot Crane

"as quickly as he grabbed the money." Dunlap was described as "very cool,

very calm, and very collected," with "the coldest eyes." Another teller

confirmed that Crane "did everything" Dunlap asked, "and he shot her for

no reason."

Crane died as a result of the shotgun blast to her

chest. A bystander wrote down a description of Dunlap and the car

including the license number.

Later that afternoon, Dunlap abandoned the Chevette

after a chase and escaped into nearby woods, but was later apprehended.

After being advised of his Miranda rights, Dunlap admitted he had robbed

the Soda Springs bank and shot the teller.

During interviews on October 17 and 19, Dunlap again

admitted to police that he robbed the bank and shot Crane, because "she

set the alarm to the police and she didn't give me all the money."

Dunlap asserted, however, he "never intended to kill her." Because he

had loaded the shotgun with bird shot, he thought she would just wind up

in the hospital.

In the same interviews, Dunlap admitted he shot

Bolanos with the crossbow in order to get her car, check book, and

credit cards. Dunlap recognized "it didn't have to be done, it

is just I was broke, I had no money. I was hardly working." He felt a "little

bit of sadness" because "I liked her a little bit." In the October 19

interview, Dunlap also claimed that an ex-boyfriend of Bolanos gave him

money to kill her, but no evidence at trial supported that assertion.

On October 16, Dunlap consented to a search of the

car. On October 18, police searched the Chevette and found the crossbow,

the shotgun, numerous credit card receipts signed by Dunlap as "Steve

Bolanos," Belinda's personal belongings, and a large quantity of loose

cash.

The grand jury indicted Dunlap for two aggravated

murder counts relating to Bolanos, murder done with prior calculation

and design (count I) and felony murder (count II), as well as aggravated

robbery (count III). Each murder count included two death penalty

specifications alleging murder as a "course of conduct" and murder

during an aggravated robbery in violation of R.C. 2929.04(A)(5) and (7).

At trial, Dunlap asked his attorneys not to challenge

the prosecution's guilt-phase evidence or to cross-examine prosecution

witnesses. Defense did move to suppress Dunlap's pretrial statements to

police and also contested Dunlap's guilt as to the "course of conduct"

death penalty specification. The jury convicted Dunlap as charged.

Evidence at Sentencing

Dunlap's mother, Patricia Dunlap, testified that

Dunlap was born in August 1968, and his stepfather adopted him in 1969.

As a youth, Dunlap played sports, served as an altar boy, a school

crossing guard, and a cub scout, and was in the county sheriff's cadet

program. In high school, he was in several plays and played the school

mascot. In two years of college, he studied business law, communications,

and drama and had the lead in a college play. When he was twenty-one, he

got married and had a son, but the marriage lasted less than a year.

Until his divorce, he was never in trouble with the law, and he even ran

for political office twice.

John Dunlap, his stepfather, testified he was a good

son, who was introverted in grade school, but he blossomed in high

school. At eighteen, he was rebellious. Dunlap's grandmother spoke

highly of him. His sister testified that he had few friends and started

rebelling against his parents in high school. In college, Dunlap did

well and loved acting. After his marriage, his wife had a child, and he

was "a very loving father." He went "over the edge" when his wife

divorced him less than a year later.

His mother thought Dunlap "always had mental problems."

When he was twelve, his mother took him for counseling and therapy, but

that stopped when he told her, "I just can't go anymore." He reportedly

had comprehension problems and a learning disability. In January 1991,

police arrested Dunlap for harassing his ex-wife. After some time in

jail, he was admitted at a mental health facility. That facility's

records report that Dunlap was "manipulative" and prone to violence, and

he had a history of depression, temper outbursts, and possible

hallucinations. Those records reflect a diagnosis of disassociative

disorder, intermittent explosive disorder, depressive disorder, and

personality disorder with a possible partial complex seizure disorder.

When released from that facility, Dunlap went back to

jail and then to Madison State Hospital in Indiana. In June 1991, he

escaped from Madison and went to Cincinnati. His family did not see him

again until after his October 1991 arrest in Idaho.

When his family first talked and met with Dunlap

after his October arrest, he seemed like a different person. Dunlap's

voice showed "no feeling, no warmth, no emotion." Dunlap had an

unfamiliar "hideous laugh" and "cold, glaring stare." Yet his mother,

sister, and grandmother all agreed that Dunlap, after time, showed

remorse in jail. Dunlap told his grandmother he was sorry for what he

had done and had asked God to forgive him.

In an unsworn statement, Dunlap said "I am but a man

who thought he was pushed to the edge of desperation, living in dire

straights [sic]." Now, he felt "sorry for what [he's] done." As to the

bank robbery, he "did not intend, calculate or design the death of the

teller." When he thought she pushed the alarm, his "anger and

frustration turned to rage," and he shot her. The "same pent up anger

and rage led to [his] crime here in Ohio." On the streets of Cincinnati,

he lived "on the razor's edge of sanity struggling every day to survive."

He had nowhere to stay but in Bolanos's car. He had "very little money [and]

wore the same clothes.*** The fear, anxiety, frustration and desperation

ate at [him] more and more each day." He challenged the jury that "If

any one of you can *** place yourself in my situation and state of mind,

[and say] you would have done different, then you're simply dealing in

lunacy and can't possibly say one way or the other."

He told the jury, "I don't want you to think I'm

trying to excuse what I've done, I am not, nor am I trying to lessen the

fact that two women are dead. I'm sorry for what I've done." Further, he

said, "I care about my family, my friends, and my son, and the people I

hurt, and ask them to forgive me." Now, he hopes for "a chance to

rehabilitate" himself in prison. "And though I took two lives, I do not

deserve to die."

In rebuttal, Dr. Michael Estess, a board-certified

psychiatrist, testified via videotape that he had interviewed Dunlap and

reviewed various records. In his view, Dunlap had "personality disorders,"

including "passive-aggressive," "histrionic" and "explosive" disorder.

These disorders did not constitute a mental disease or defect, and

Dunlap understood right from wrong and could conform his actions to law.

Estess agreed that Dunlap might possibly have some level organic brain

dysfunction, but even if that were true, it had no particular

significance or relevance. Estess disbelieved Dunlap's claims of

occasional blackouts or hallucinations; instead he thought Dunlap was

prone to "theater," "embellishment," and even "malingering."32

Also, in rebuttal, a reporter testified that he had

interviewed a Tim Dunlap by phone after his Ohio arraignment. The

reporter satisfied himself the caller was Dunlap because of

the caller's personal knowledge. When asked about remorse, Dunlap

replied, "Yeah, I've got to regret I didn't get away." In surrebuttal,

Dunlap's mother testified that he was still agitated, upset, and

confused when he first returned to Ohio, but he later changed and became

truly sorry. More recently, Dunlap had told another reporter that he was

sorry and "wished things could have turned out differently."

After considering the evidence, the jury recommended

the death penalty on both aggravated murder counts. The trial court

agreed and sentenced Dunlap to death on each murder count. The court of

appeals affirmed Dunlap's convictions and death penalty.

The cause is now before this court upon an appeal as

of right.

Joseph T. Deters, Hamilton County Prosecuting

Attorney, and Philip R. Cummings, Assistant Prosecuting Attorney, for

appellee.

Elizabeth E. Agar, for appellant.

Pfeifer, J. Dunlap presents fifteen propositions of

law for our consideration. We have considered Dunlap's propositions of

law, independently weighed the statutory aggravating circumstances

against the evidence presented in mitigation, and reviewed the death

penalty for appropriateness and proportionality. Upon review, and for

the reasons which follow, we affirm the judgment of the court of appeals.

I. Admission of Confession

In his twelfth proposition of law, Dunlap argues the

trial court erred in failing to suppress his pretrial statements to the

police. At a pretrial hearing, Dunlap testified that Idaho police

officers manhandled and threatened him when they arrested him. He

claimed he waived his Miranda rights "out of fear of what might happen"

because "they were going to hurt me if I didn't say it was me." Dunlap

also claimed that he requested counsel several times before

interrogation, but the police ignored those requests. Dunlap admitted he

signed waivers of rights and submitted to interviews on October 16, 17

and 19.

Of course, if Dunlap did request counsel, and police

ignored the request and continued questioning him, his statements would

be inadmissible. When counsel is requested, interrogation must cease

until a lawyer is provided or the suspect reinitiates the interrogation.

Arizona v. Roberson (1988), 486 U.S. 675, 108 S.Ct. 2093, 100 L.Ed.2d

704; Edwards v. Arizona (1981), 451 U.S. 477, 101 S.Ct. 1880, 68 L.Ed.2d

378. However, the record of the suppression hearing supports a finding

that Dunlap voluntarily waived his rights and never requested to consult

counsel before agreeing to be interviewed by police or while being

interviewed. The October 16 interview was videotaped, and the interviews

on October 17 and 19 were audiotaped. The tapes show that during hours

of interviews, police readvised or reminded Dunlap of his rights several

times, and he signed two separate waivers of rights. At no time during

these taped interviews did appellant decline to answer questions or ask

to consult a lawyer before answering questions. The police never

threatened appellant or promised him anything to secure his cooperation.

On October 19, appellant freely talked with Cincinnati police officers

after again waiving his Miranda rights.

Admittedly, at one point during the taping of

Dunlap's October 17 statement, the police chief briefly referred to the

fact that the interview had been interrupted so Dunlap could sign "a

document for the Court." That document "has to do with appointing an

attorney, which you [Dunlap] do not have enough funds for."

However, the context makes it clear that this request

concerned the appointment of counsel for future court hearings. Dunlap

did not ask to consult with a lawyer before answering questions nor did

he ask for a lawyer to be present during any interviews. "The rationale

underlying Edwards is that the police must respect a suspect's wishes

regarding his right to have an attorney present during custodial

interrogation." Davis v. United States (1994), 512 U.S. , , 114 S.Ct.

2350, 2355, 129 L.Ed.2d 362, 372. As Davis held, "the suspect must

unambiguously request counsel." Id. at , 114 S.Ct. 2355, 129 L.Ed.2d at

371. Dunlap made no unambiguous request to consult counsel. See

Connecticut v. Barrett (1987), 479 U.S. 523, 107 S.Ct. 828, 93 L.Ed.2d

920; United States v. Mills (C.A.6, 1993), 1 F.3d 414. Instead, he

simply took a short break to sign a document to allow the Idaho court to

appoint him an attorney to represent him in future court proceedings.

Thereafter, Dunlap resumed the interview with the police chief that

Dunlap had himself initiated.

Moreover, that break in appellant's taped October 17

confession occurred relatively late in the course of that interview--two

thirds of the way through, in fact. After that point in the interview,

the police chief and Dunlap mostly discussed the Idaho robbery, not the

Ohio murder. Since abundant other evidence established appellant's guilt

of that second "course of conduct" murder, admitting the last portion of

appellant's October 17 confession or even his October 19 statement, even

if error, was harmless beyond a reasonable doubt.

"[T]he weight of the evidence and credibility of

witnesses are primarily for the trier of the facts. *** This principle

is applicable to suppression hearings as well as trials." State v.

Fanning (1982), 1 Ohio St.3d 19, 20, 1 OBR 57, 58, 437 N.E.2d 583, 584.

Accord State v. DePew (1988), 38 Ohio St.3d 275, 277, 528 N.E.2d 542,

547.

The trial court's decision to admit the statements

rests upon substantial evidence. We find no basis to reverse the trial

court's decision and reject the interview tapes and police officers'

testimony in favor of Dunlap's claims. We reject Dunlap's twelfth

proposition.

II. Multiple Charges and Specifications

In his first proposition of law, Dunlap correctly

argues that the trial court erred by submitting two charges of

aggravated murder to the jury for separate penalty determinations and in

imposing two death sentences. Since both charges "involve the same

victim, they merge." State v. Lawson (1992), 64 Ohio St.3d 336, 351, 595

N.E.2d 902, 913; State v. Huertas (1990), 51 Ohio St.3d 22, 28, 553 N.E.2d

1058, 1066.

However, we find this error harmless beyond a

reasonable doubt. State v. Cook (1992), 65 Ohio St.3d 516, 526-527, 605

N.E.2d 70, 82; State v. Brown (1988), 38 Ohio St.3d 305, 317-318, 528

N.E.2d 523, 538-539. Moreover, the court of appeals explicitly merged

the two murder counts and approved only a single death sentence.

Accordingly, we recognize that only a single death sentence remains but

otherwise reject Dunlap's first proposition.

In his second proposition of law, Dunlap argues that

the trial court's submission to the jury of the R.C. 2929.04(A)(7),

felony-murder death specification, in counts I and II, prejudiced his

rights to a fair sentencing determination. Dunlap argues the

specifications and instructions improperly multiplied the felony-murder

aggravating circumstance into two aggravating circumstances as

proscribed in State v. Penix (1987), 32 Ohio St.3d 369, 370-372, 513 N.E.2d

744, 746-747.

As Penix notes, 32 Ohio St.3d at 371, 513 N.E.2d at

746, "[p]rior calculation and design is an aggravating circumstance only

in the case of an offender who did not personally kill the victim." In

this case, the sentencing instructions referred to whether "the offense

of aggravated murder was committed while the defendant was committing

aggravated robbery or was committed with prior calculation and design

***." (Emphasis added.) By so doing, the instructions incorrectly

described the aggravating circumstance. However, unlike the court in

Penix, the court here did not multiply a single felony murder

specification into two aggravating circumstances. The jury's findings of

guilt, as well as the specifications in the indictment, correctly stated

this aggravating circumstance. Dunlap did not object to the instruction.

We find no plain error and reject Dunlap's second proposition. See, also,

State v. Cook, 65 Ohio St.3d at 527, 605 N.E.2d at 82.

III. Exclusion of Jurors

In his third proposition, Dunlap argues that

excluding jurors who could not vote for the death penalty violated his

right to a jury composed of a fair cross-section of the community.

However, death-qualifying a jury "does not deny a capital defendant a

trial by an impartial jury." State v. Jenkins (1984), 15 Ohio St.3d 164,

15 OBR 311, 473 N.E.2d 264, paragraph two of the syllabus; Lockhart v.

McCree (1986), 476 U.S. 162, 106 S.Ct. 1758, 90 L.Ed.2d 137. Here, the

record demonstrates those excluded held views which "would prevent or

substantially impair the performance" of duties in accordance with the

juror's "instructions and oath." State v. Rogers (1985), 17 Ohio St.3d

174, 17 OBR 414, 478 N.E.2d 984, paragraph three of the syllabus,

following Wainwright v. Witt (1985), 469 U.S. 412, 105 S.Ct. 844, 83

L.Ed.2d 841. Thus, Dunlap's third proposition lacks merit. State v.

Tyler (1990), 50 Ohio St.3d 24, 30, 553 N.E.2d 576, 586.

IV. Mercy Instruction

In his fourth proposition, Dunlap argues the trial

court erred in its penalty phase instructions by not allowing the jury

to consider sympathy and by failing to instruct on mercy. However, the

court properly instructed the jury to exclude sympathy. State v. Jenkins,

15 Ohio St.3d 164, 15 OBR 311, 473 N.E.2d 264, paragraph three of the

syllabus; State v. Steffen (1987), 31 Ohio St.3d 111, 125, 31 OBR 273,

285, 509 N.E.2d. 383, 396. The court also properly refused to instruct

on mercy. State v. Lorraine (1993), 66 Ohio St.3d 414, 417, 613 N.E.2d

212, 216; State v. Hicks (1989), 43 Ohio St.3d 72, 78, 538 N.E.2d 1030,

1036.

V. Sufficiency of Evidence

In his fifth and sixth propositions, Dunlap argues

the evidence was insufficient to establish his guilt of the R.C.

2929.04(A)(5) "course of conduct" specification alleging "the purposeful

killing" or attempt to kill two or more persons. Dunlap argues he did

not intend to kill Crane.

In a review for sufficiency, the evidence must be

considered in a light most favorable to the prosecution. Jackson v.

Virginia (1979), 443 U.S. 307, 99 S.Ct. 2781, 61 L.Ed.2d 560; State v.

Davis (1988), 38 Ohio St.3d 361, 365, 528 N.E.2d 925, 930. "[T]he weight

to be given the evidence and the credibility of the witnesses are

primarily for the trier of the facts." State v. DeHass (1967), 10 Ohio

St.2d 230, 39 O.O.3d 366, 227 N.E.2d 212, paragraph one of the syllabus.

We find the evidence established that Dunlap purposefully killed Crane

and thus his guilt of the "course of conduct" specification. Dunlap told

Police Chief Blynn Wilcox he was angry with Crane and shot her because "she

set the alarm to the police and she didn't give me all the money." One

teller identified Dunlap as standing at the counter, and she saw the

shotgun barrel "stick out from the edge of the teller counter."

According to her, Dunlap "did not hesitate. As soon as he had the money,

he shot her." Another teller described Dunlap as "very determined" and "very

deliberate," and the force was so strong Crane "was even blown out of

her shoes." Dunlap's deliberate close-range firing of a shotgun at

Crane's chest, whatever the type of shells, proved his intent to kill.

"[A] firearm is an inherently dangerous instrumentality, the use of

which is reasonably likely to produce death[.]" State v. Widner (1982),

69 Ohio St.2d 267, 270, 23 O.O.3d 265, 266, 431 N.E.2d 1025, 1028,

followed in State v. Seiber (1990), 56 Ohio St.3d 4, 14, 564 N.E.2d 408,

419. Accord State v. Johnson (1978), 56 Ohio St.2d 35, 39, 10 O.O.3d 78,

81, 381 N.E.2d 637, 640.

VI. Other Evidentiary Issues

In his thirteenth proposition of law, Dunlap argues

the trial court erred in allowing rebuttal testimony from reporter

Hopkins in the mitigation phase. In a phone call, Hopkins asked the

caller, who named himself Tim Dunlap, about remorse. Dunlap reportedly

said, "Yeah, I've got to regret I didn't get away." In extensive voir

dire, Hopkins explained why he was satisfied that Dunlap was the caller.

Hence, the trial court did not abuse its discretion in allowing Hopkins

to testify. "The admission or exclusion of relevant evidence rests

within the sound discretion of the trial court." State v. Sage (1987),

31 Ohio St.3d 173, 31 OBR 375, 510 N.E.2d 343, paragraph two of the

syllabus. See, also, Evid.R. 611 and 901.

The prosecutor's failure to list Hopkins as a

potential witness, or to eject him from the courtroom under a witness

separation order, did not mandate the exclusion of Hopkins as a witness.

A rebuttal witness's name need not always be disclosed. See State v.

Howard (1978), 56 Ohio St.2d 328, 333, 10 O.O.3d 448, 451, 383 N.E.2d

912, 915-916; State v. Lorraine, 66 Ohio St.3d at 422, 613 N.E.2d at

220. Moreover, the exclusion of testimony for an asserted discovery

violation is discretionary. State v. Scudder (1994), 71 Ohio St.3d 263,

269, 643 N.E.2d 524, 530; State v. Wiles (1991), 59 Ohio St.3d 71, 78,

571 N.E.2d 97, 110. Also, any error was harmless. Abundant other

evidence suggests Dunlap lacked remorse, including testimony from Dr.

Estess, Dunlap's family, and even Dunlap's unsworn statement.

In his fourteenth proposition of law, Dunlap argues

the trial court erred in admitting four gruesome photographs, including

one autopsy photo and three crime scene photos. Under Evid.R. 403 and

611(A), the admission of photographs is left to a trial court's sound

discretion. State v. Jackson (1991), 57 Ohio St.3d 29, 37, 565 N.E.2d

549, 559; State v. Maurer (1984), 15 Ohio St.3d 239, 264, 15 OBR 379,

401, 473 N.E.2d 768, 791. We are satisfied the trial court did not abuse

its discretion in admitting these photographs. See State v. Morales

(1987), 32 Ohio St.3d 252, 257, 513 N.E.2d 267, 273; Maurer, at

paragraph seven of the syllabus Thus, we reject both propositions.

VII. Constitutional Issues

In his eighth proposition, Dunlap challenges the

constitutionality of the felony-murder provisions in Ohio's death

penalty statute. However, we have long rejected those claims. See State

v. Henderson (1988), 39 Ohio St.3d 24, 528 N.E.2d 1237, paragraph one of

the syllabus. See, also, Lowenfield v. Phelps (1988), 484 U.S. 231, 108

S.Ct. 546, 98 L.Ed.2d 568; State v. Benner (1988), 40 Ohio St.3d 301,

306, 533 N.E.2d 701, 708.

We rejected challenges such as Dunlap's ninth

proposition in State v. Beuke (1988), 38 Ohio St.3d 29, 38-39, 526 N.E.2d

274, 285. See, also, State v. Bedford (1988), 39 Ohio St.3d 122, 132,

529 N.E.2d 913, 923; State v. Sowell (1988), 39 Ohio St.3d 322, 335-336,

530 N.E.2d 1294, 1308-1309. Dunlap's tenth proposition also lacks merit.

See State v. Jenkins, 15 Ohio St.3d at 176, 15 OBR at 321-322, 473 N.E.2d

278-279; State v. Steffen, 31 Ohio St.3d 111, 31 OBR 273, 509 N.E.2d

383, at paragraph one of the syllabus.

VIII. Other Sentencing Issues

In his seventh proposition, Dunlap correctly argues

the trial court erred by allowing the prosecutor to improperly refer to

the nature and circumstances of the offense as aggravating circumstances.

Admittedly, "the nature and circumstances of an offense are not a

statutory aggravating circumstance and cannot be considered as such."

State v. Lott (1990), 51 Ohio St.3d 160, 171, 555 N.E.2d 293, 304; State

v. Davis, 38 Ohio St.3d at 370-371, 528 N.E.2d at 934. However, we find

any error harmless, since the prosecutor's misstatement did not

materially prejudice Dunlap.

The trial court's sentence instructions explained to

the jury the weighing process and the aggravating circumstances, and

these instructions negated the prosecutor's misstatements. See State v.

Greer (1988), 39 Ohio St.3d 236, 251, 530 N.E.2d 382, 400. "Moreover,

the prosecutor could legitimately refer to the nature and circumstances

of the offense, both to refute any suggestion that they were mitigating

and to explain why the specified aggravating circumstance *** outweighed

mitigating factors." State v. Combs (1991), 62 Ohio St.3d 278, 283, 581

N.E.2d 1071, 1077. See, also, State v. Stumpf (1987), 32 Ohio St.3d 95,

512 N.E.2d 598, paragraph one of the syllabus. In his eleventh

proposition, Dunlap argues the trial court erred in not requiring the

jury, as he requested, to articulate the method by which the jury

weighed the aggravating circumstances against mitigation evidence. In

effect, Dunlap argues that the jury should make special findings and

justify their sentencing verdict.

However, the Constitution does not require a jury in

a capital case to render a special verdict or special findings. See

State v. Jenkins, 15 Ohio St.3d at 212, 15 OBR at 352, 473 N.E.2d at

306; Hildwin v. Florida (1989), 490 U.S. 638, 109 S.Ct. 2055, 104 L.Ed.2d

728. Additionally, the General Assembly mandated special findings from

the jury as to aggravating circumstances in R.C. 2929.03(B). However,

the General Assembly did not require the jury to explain its findings in

the sentencing recommendation. Hence, we reject this proposition.

IX. Reservation of Issues

In his fifteenth proposition, Dunlap asks this court

to consider other trial errors which may exist even though he failed to

argue or specify such errors. However, absent plain error, Dunlap waived

any such issue by not raising them here and in the court of appeals.

State v. Williams (1977), 51 Ohio St.2d 112, 5 O.O.3d 98, 364 N.E.2d

1364. In any event, we find no plain error that is so grievous that "but

for the error, the outcome of the trial clearly would have been

otherwise." State v. Long (1978), 53 Ohio St.2d 91, 7 O.O.3d 178, 372

N.E.2d 804, at paragraph two of the syllabus. Proof of Dunlap's guilt

from his statements and the results of the car search was compelling.

Our independent reassessment of the sentence will negate the effect of

any unasserted error affecting the sentence.

X. Independent Sentence Assessment

After independent assessment, we find the evidence

clearly proves the aggravating circumstances for which Dunlap was

convicted, i.e., murder during a robbery and as a "course of conduct" in

purposefully killing or attempting to kill more than one person. As to

possible mitigating factors, we find nothing in the nature and

circumstances of the offense to be mitigating. Dunlap lured his

girlfriend to a secluded park area, blindfolded her, and promised her a

surprise. Then, he led her into the woods and cruelly shot her twice

with a crossbow. He left her to die alone, and killed her simply to

secure her possessions: an old car, credit cards, and checkbook.

Dunlap's history and background provide modest

mitigating features. However, his childhood and life as a young adult

are mostly unremarkable. He had the advantages of a stable home, loving

parents, and a solid education. Although regularly employed, he did not

keep jobs very long. Unfortunately, an early marriage turned sour in its

first year, and he became entangled in courts and mental hospitals.

After living homeless in Cincinnati, he turned on Bolanos, who had

befriended him. Dunlap denied use of drugs or excessive use of alcohol.

His admitted personality disorders, confirmed by hospital records and

Dr. Estess's testimony, provide only slight mitigation. Additionally,

the fact he has a son and a family who love him deserves some weight.

Yet, we find nothing in his character to be mitigating.

The statutory mitigating factors of age and lack of a

significant criminal history are relevant and deserve modest weight. See

R.C. 2929.04(B)(4) and (5). Dunlap had no criminal convictions prior to

this offense. Although Dunlap was twenty-three at the time of the

offense, he did have some college and was mature.

We find no other applicable statutory mitigating

factors in R.C. 2929.04(B)(1) to (6). His "personality disorders" were

not a mental disease or defect as Dr. Estess confirmed. See R.C.

2929.04(B)(3); State v. Fox (1994), 69 Ohio St.3d 183, 192, 631 N.E.2d

124, 131-132. As to "other factors," in R.C. 29292.04(B)(7), Dunlap's

cooperation with police was mitigating evidence. However, no significant

"other factors," as specified in R.C. 2929.04(B)(7), are relevant. His

personality disorders have already been considered as part of his

background. Some evidence exists that Dunlap expressed remorse, but

other evidence, including his unsworn statement, contradicts his claims

of remorse. Under the circumstances, we assign little weight to Dunlap's

remorse.

In our view, the aggravating circumstances outweigh

the modest mitigating factors present in this case beyond any reasonable

doubt. Dunlap killed Bolanos to rob her, and he robbed her using

treachery and extreme violence. Then, he stole her car, assumed the

identity of her fictitious husband, Steve Bolanos, and used her credit

cards to travel across the country. In Idaho, he killed another woman,

thus establishing the calculated "course of conduct." Even when

considered collectively, the mitigating factors he raises deserve only

modest weight and offer no redeeming value. Thus, we find the death

penalty is appropriate.

We find the death penalty in this case is neither

excessive nor disproportionate when compared with the penalty imposed in

similar cases of felony murder. See State v. Loza

(1994), 71 Ohio St.3d 61, 641 N.E.2d 1082; State v. Woodard (1993), 68

Ohio St.3d 70, 623 N.E.2d 75; State v. Green (1993), 66 Ohio St.3d 141,

609 N.E.2d 1253; State v. Mills (1992), 62 Ohio St.3d 357, 582 N.E.2d

972. We further find the death sentence proportionate when compared with

similar "course of conduct" murders. See State v. Loza, supra; State v.

Grant (1993), 67 Ohio St.3d 465, 620 N.E.2d 50; State v. Lorraine, 66

Ohio St.3d 414, 613 N.E.2d 212; State v. Hawkins (1993), 66 Ohio St.3d

339, 612 N.E.2d 1227; State v. Montgomery (1991), 61 Ohio St.3d 410, 575

N.E.2d 167; State v. Frazier (1991), 61 Ohio St.3d 247, 574 N.E.2d 483;

State v. Combs, 62 Ohio St.3d 278, 581 N.E.2d 1071.

Accordingly, the judgment of the court of appeals is

affirmed.

Judgment affirmed.

Moyer, C.J., Douglas, Wright, Resnick, F.E. Sweeney

and Cook, JJ., concur.

FOOTNOTES:

1 In Idaho, Dunlap pled guilty to Crane's murder and

was sentenced to death. Upon appeal, the Idaho Supreme Court affirmed

his death sentence. See State v. Dunlap (1993), 125 Idaho 530, 873 P.2d

784.

2 The video deposition lasted one hour and seventeen

minutes, but was stopped after an extensive cross-examination because of

lack of tape. No issue has been raised as to that.