In the Supreme Court of Indiana

Cause No. 49S00-9801-DP-55

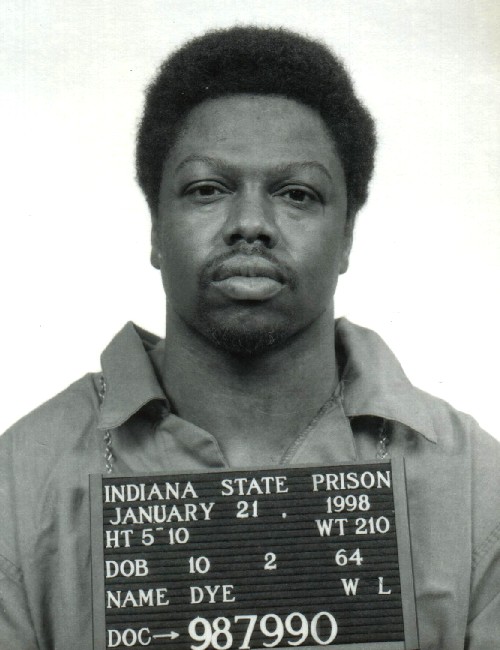

Walter Dye, Appellant (Defendant Below),

v.

State of Indiana, Appellee (Plaintiff Below).

Appeal From The Marion Superior Court

The Honorable Patricia J. Gifford, Judge

Cause No. 49G04-9608-CF-112831

On Direct Appeal

September 30, 1999

BOEHM, Justice.

Walter Dye was convicted of the murder of Hannah

Clay, age fourteen, Celeste Jones,age seven, and Lawrence Cowherd

III, age two. A jury recommended that the death sentence be imposed,

and the trial court imposed the death sentence. In this direct

appeal Dyecontends that (1) the State committed numerous discovery

violations; (2) his right to be freefrom self-incrimination was

violated when he was questioned without Miranda warnings; (3)the

trial court erred by excusing a juror for cause on the State's

motion and failing to excusetwo jurors for cause upon his motion;

(4) his jury was not selected from a representativecross-section of

the community; (5) the trial court erred when it modified his

tenderedpenalty phase instruction on clemency; and (6) death is not

the appropriate sentence basedon the weighing of aggravating and

mitigating circumstances and the “residual doubt” of hisguilt. We

affirm.

Factual and Procedural Background

Myrna Dye decided to leave Dye, her husband of

four years, in early July, 1996. According to Myrna, the couple

constantly fought, their sexual relationship had becomenonexistent,

and Dye had become “real grouchy” toward Myrna's daughter Hannah

Clay,who lived with the couple. On Monday July 15, Myrna signed a

lease for a furnishedapartment located seven blocks from where she

and Dye resided. That evening Dyeconfronted Myrna about her plans to

leave, and she confirmed his suspicions. According toMyrna, Dye

appeared “kind of angry” and told her “I can have something done to

you andhave an alibi because I would be at work.” He added, “I'm

going to make sure you sufferthe rest of your life, and everybody is

going to know who been there.” The next day, whileDye was at work,

Myrna and Hannah moved out.

The following Sunday, July 21, Myrna and another

of her daughters, Potrena Jones, went to work the night shift at a

nursing home. Hannah remained at the apartment withMyrna's two

grandchildren, Lawrence Cowherd III, age two, and Celeste Jones, age

seven.Lawrence was Potrena's son, and Celeste was the daughter of

Theresa Jones, another ofMyrna's daughters. Theresa was supposed to

have worked the afternoon shift at the samenursing home where Myrna

and Potrena went to work, but had not shown up for work.Myrna was

angry and called Theresa at the home Theresa shared with Potrena and

their twochildren. Theresa's boyfriend, John Jennings, eventually

answered the phone, and Myrnahad harsh words for both of them.

At the end of their shift, Myrna and Potrena took

the bus home. As they approachedthe apartment at about 8:00 a.m.,

they saw several police cars. They soon learned thatHannah's

partially nude body had been found in the apartment and that Celeste

andLawrence were missing. An autopsy later revealed that Hannah had

been beaten with whatthe pathologist believed to be a crowbar and a

hammer. Her body sustained blunt forceinjuries as well as ligature

strangulation and stab wounds to the neck and hand. The bluntforce

injuries were applied with such force “to have crushed the front of

the chest wall backtoward the spine, crushing the heart and the

lungs in between.” A rape kit was collectedduring the autopsy.

Although the swabs of her body showed no evidence of sperm, a

wetwashcloth containing seminal fluid was found on a bed near

Hannah's body.

A search for Celeste and Lawrence was promptly

begun. At about 2:00 p.m., a policeofficer found a bundled comforter

among some tall weeds along an alley near Myrna'sapartment. Two

trash bags containing the lifeless bodies of Celeste and Lawrence

were found in the comforter. Both children had sustained injuries

consistent with being hit on thehead with a fist. Lawrence had also

been hit in the left lower chest and liver, and Celeste hadbeen

stabbed with a knife. Lawrence had been strangled with a lamp cord

taken fromMyrna's apartment, and Celeste had been strangled with an

extension cord.

Investigators collected a great deal of physical

evidence that pointed to Dye as thekiller. Dye's palmprints were

found on a nightstand near Hannah's body. Dye's fingerprint,made in

Hannah's blood, was found on a clothing tag near her body. Dye's

shoeprints werefound on papers strewn on the bedroom floor. One of

these papers had the palmprints inHannah's blood from both Dye and

Hannah. Police seized Dye's shoes during the executionof a search

warrant at his residence, and Hannah's blood was found in the inner

stitching andfibers of the shoes. Finally, analysis of DNA in the

sperm found on the washcloth matchedDye's with odds of 1 in 39

billion.See footnote

1

Dye initially told police that he had never been

to Myrna's apartment and had not lefthis residence on the night of

the murders. However, he testified at trial that he walked to

getcigarettes at about 2:45 a.m. on the night of the killing and

kept walking to Myrna'sapartment, because Myrna had told him days

earlier that she would be off work on Sundaynight. He testified that

upon his arrival at Myrna's apartment he found the door open,walked

inside, saw a foot, walked over to Hannah's body, touched her,

concluded she was dead, and left. He did not call the police. He

returned home but could not sleep, andclocked in at work at 5:26

a.m.

A jury convicted Dye of three counts of murder.

The jury recommended that thedeath penalty be imposed, and the trial

court followed that recommendation and sentencedDye to death.

I. Alleged Discovery Violations

Dye contends that the State violated the

discovery rules of Marion County bybelatedly disclosing several

pieces of evidence. He also argues that these “egregious”violations

deprived him of his “state and federal due process rights and his

right to presenta defense.”See footnote

2

Trial courts are given wide

discretion in discovery matters because they havethe duty to promote

the discovery of truth and to guide and control the proceedings.

Braswell v. State, 550 N.E.2d 1280, 1283 (Ind. 1990). They are

granted deference indetermining what constitutes substantial

compliance with discovery orders, and we willaffirm their

determinations as to violations and sanctions absent clear error and

resultingprejudice. Id.; Kindred v. State, 524 N.E.2d 279, 287 (Ind.

1988). When remedial measuresare warranted, a continuance is usually

the proper remedy, but exclusion of evidence maybe appropriate where

the violation “has been flagrant and deliberate, or so misleading or

insuch bad faith as to impair the right of fair trial.” Kindred, 524

N.E.2d at 287.

A. The Crowbar

The day after the killings a crowbar was

discovered in the alley running behindMyrna's apartment. The

crowbar's existence was promptly disclosed to the defense, as wasa

report that it had been tested for the presence of human blood and

tested positive. OnMarch 13, 1997, detectives, at the direction of

the prosecutor's office, again interviewedMyrna and Theresa. Myrna

confirmed that Dye had owned a crowbar similar or identicalto the

one found. The detective promptly advised a deputy prosecutor of

what he hadlearned, and the deputy instructed him to write an

interdepartmental memo memorializingthe conversation. The detective

wrote the memo and gave it to a paralegal in the prosecutor'soffice.

The paralegal apparently misfiled the memo and failed to route it to

the prosecutorsor defense attorneys who would try the case.See

footnote

3

As a result, Myrna's statements that

thecrowbar belonged to Dye were not disclosed to the defense until

August 13, 1997, threeweeks before Dye's trial was to begin. Upon

receipt of the memo, defense counsel filed a motion to exclude any

evidence relating to the crowbar, contending that the State's

belateddisclosure of the interdepartmental memo “is in total and

complete violation of the Rules ofDiscovery of the Marion Superior

Court, is contemptuous, and is deserving of the most severe

sanctions.” The trial court conducted a hearing on the motion and

denied the motionto exclude the evidence, observing that “[t]here

are other remedies available to thedefendant.”

Dye points to Rule 7 of the Rules of Organization

and Procedure of the MarionSuperior Court, Criminal Division.

Section 1(a) of that rule provides that “[t]he court atinitial

hearing will automatically order the State to disclose and furnish

all relevant items andinformation under this Rule to the defendant(s)

within twenty (20) days from the date of theinitial hearing . . . .”

The information here, however, was not known to exist within

twentydays of the initial hearing, but rather was uncovered by the

State months later during thecourse of its preparation for trial.

Under these circumstances, the State nevertheless had theobligation

to make timely disclosure of the evidence to the defense. The five

month delayhere can hardly be viewed as timely. Nevertheless,

accepting the State's explanation at facevalue, the belated

disclosure was not flagrant or deliberate, and disclosure

neverthelessoccurred three weeks before trial. This was sufficient

time to allow defense counsel to re-depose the necessary witnesses

before trial, which was done. Under these circumstances,the trial

court's denial of Dye's request to exclude the evidence and motion

for continuancewas not clear error, and in any event he has not

demonstrated any resulting prejudice.See footnote

4

Kindred, 524 N.E.2d at 287.

Dye also asserts error based on the State's

belated disclosure of Theresa Jones' March13 statement to

detectives. Theresa told police that she had owned a crowbar similar

to theone described by Myrna, but after being shown the crowbar

found near the crime scene toldpolice that it was not hers. She also

told police that she could not recall whether her crowbarwas in the

trunk of her car when it was repossessed. This conversation was

alsomemorialized in the same misfiled memo described above and not

disclosed to the defenseuntil the memo surfaced three weeks before

trial. Dye argues that, because of the belateddisclosure, he had an

“inadequate opportunity to effectively use this information. Had

timeallowed, the defense could have explored the repossession of

Theresa's car and if thecrowbar was, indeed, in the trunk.” He

contends that the State's belated disclosure of thisevidence

constitutes a violation of Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83, 83 S. Ct.

1194, 10 L. Ed.2d 215 (1963). We disagree.

As a threshold matter, there was no Brady

violation because the evidence wasdisclosed to the defense three

weeks before trial, see Williams v. State,714 N.E.2d 644, 648-49

(Ind. 1999), and the defense had ample opportunity to pursue any

avenues raised by itsdisclosure and to adjust its strategy

accordingly. Moreover, Brady and its progeny apply toevidence that

is “material” to guilt or punishment, i.e., evidence that creates a

reasonableprobability of a different result of a proceeding. See,

e.g., United States v. Bagley, 473 U.S.667, 682, 105 S. Ct. 3375, 87

L. Ed. 2d 481 (1985). Theresa's statement to the police ishardly

exculpatory or material to Dye's guilt. She told police that her

crowbar was differentfrom the one found near the crime scene, and

questioning those individuals who repossessed her car would, in the

best case scenario to the defense, have disclosed that no crowbar

wasfound in her trunk. This would not exculpate Dye nor would it

materially add to his defensein light of the overwhelming physical

evidence connecting him to the crime.

B. Fingerprints and DNA Testing of John

JenningsSee footnote

5

On August 22, 1997, after her deposition was

taken by the defense, fingerprintexaminer Diane Donnelly took the

fingerprints of Theresa Jones' boyfriend, John Jennings. Donnelly

generated a report, dated September 2, the first day of jury

selection, that compareda number of unidentified latent fingerprints

from the crime scene with those submitted byJennings, and found no

matches. According to the State, it did not receive Donnelly's

reportuntil the evening of September 9, and it turned the report

over to the defense early thefollowing morning. In addition, the

prosecutor's office directed a detective to transportJennings for a

blood draw on August 22. DNA analysis excluded Jennings as the

contributorof any of the unknown DNA from the crime scene. Defense

counsel objected to both theadmission of the fingerprint comparisons

and DNA analysis of Jennings on the ground of itslate disclosure.

The State responded that it requested this analysis after

identifying thedefense theory that someone else, possibly Jennings,

had committed the murders. Dyeinitially sought exclusion of the

evidence, but was instead granted a continuance until thenoon hour.

The trial court observed that it agreed “with the State in that I

believe that theyhad a duty and an obligation to try to compare

these prints, even at this late date. So although it is a violation

of discovery rules, due to the circumstances there will be

nosanctions imposed.”

We find the State's explanation for the belated

disclosure more than adequate underthe circumstances. Although its

late decision to test these materials was a reasonableresponse to an

expected defense trial theory, it nevertheless ran the risk, in the

event of eithera fingerprint or DNA match, of providing the defense

with powerful evidence to bolster itscase. However, the results

instead exculpated Jennings. This at most forced a minoradjustment

to the defense theory that some unidentified person may have

committed thekillings.

Dye alleges prejudice based on his opening

statement to the jury in which he“hemmed himself in . . . by telling

the jury that there would be no dispute about the scientificevidence

. . . . [Dye] could not later challenge the scientific evidence

about which he did notyet know.” In addition, Dye's opening

statement spoke in generalities about the possibilitythat someone

other than Dye had committed the killings: “We are not going to be

able to tellyou who killed these children. We do not know.” However,

Dye made no specific mentionof Jennings by name as the possible

perpetrator during opening statement. His expresseddecision not to

challenge the scientific evidence hardly prevented him from

challengingscientific evidence not yet known at the time of his

opening statement. The trial courtgranted a continuance to allow

Dye's expert to compare the fingerprints. Had Dye's expertconcluded

that any of the prints found at the crime scene were Jennings', he

could havepresented this to the jury through his expert and also

pointed out the belated disclosure of the State's comparisons in

cross-examination of Donnelly. Dye did not offer the testimonyof his

fingerprint expert, and the obvious inference is that his expert's

conclusions weresimilar to those of Donnelly. The trial court's

continuance until the noon hour was anadequate remedy under these

circumstances and Dye has demonstrated no prejudice as aresult of

this ruling.

C. Other Alleged Violations

As a final point, Dye quotes from his pretrial

motion for continuance, filed daysbefore trial, which alleged other

discovery violations. However, Dye makes no separateargument

regarding these alleged violations and accordingly any claim of

error is waived forthe failure to present a cogent argument. Ind.

Appellate Rule 8.3(A)(7).See footnote

6

II. Failure to Provide Miranda Warnings

Dye argues that some statements he made to police

should have been suppressedbecause police failed to provide him with

the Miranda warnings before questioning him.See footnote

7

At about noon on July 22, two

detectives went to Dye's place of employment to talk to himabout

Hannah's murder and the disappearance of Lawrence and Celeste. They

informed Dye that he was neither a suspect nor under arrest but that

they needed to ask him some questionsin light of allegations by the

family that he had made threats towards Myrna. He agreed toaccompany

the detectives to the police station, and they explained that police

departmentpolicy required that he be handcuffed and placed in the

backseat during his ride there. Thehandcuffs were removed upon

arrival and Dye was taken to an interview room, where hespoke to

detectives for about forty-five minutes. Dye told the detectives

that he had neverbeen to Myrna's apartment but had a pretty good

idea where it was located. He also said thathe had never left his

residence on the night of the murder. When asked if he were

capableof committing this crime, Dye replied “[i]f I ever had the

thought, never the kids.” Thisstatement was made before the bodies

of Celeste and Lawrence had been discovered. Muchlater in the

day,See footnote

8

the detectives arranged a time on

Wednesday at which to pick Dye up fromwork to transport him for a

blood draw. Detectives explained that they sought a bloodsample

because it was possible that Hannah had been raped. At the agreed

upon time onWednesday, a detective picked Dye up at work. Dye rode,

unrestrained, in the front seat ofthe detective's car. En route to

the blood draw, the detective heard Dye breathing heavilyand asked

him what was wrong. Dye replied that he had never given a semen

sample before. The detective responded that “[a]ll we've ever agreed

to was you said you would provide ablood sample, nothing more. . .

.”

Miranda warnings are required only in the context

of custodial interrogation. SeeMiranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436,

444, 86 S. Ct. 1602, 16 L. Ed. 2d 694 (1966). Custodialinterrogation

is “questioning initiated by law enforcement officers after a person

has beentaken into custody or otherwise deprived of his freedom of

action in any significant way.” Id. The Supreme Court has further

explained interrogation as “either express questioningor its

functional equivalent.” Rhode Island v. Innis, 446 U.S. 291, 300-01,

100 S. Ct. 1682,64 L. Ed. 2d 297 (1980). Custody has been described

as “whether there [was] a 'formalarrest or restraint on freedom of

movement' of the degree associated with a formal arrest.” Stansbury

v. California, 511 U.S. 318, 322, 114 S. Ct. 1526, 128 L. Ed. 2d 293

(1994) (percuriam) (quoting California v. Beheler, 463 U.S. 1121,

1125, 103 S. Ct. 3517, 77 L. Ed. 3d1275 (1983) (per curiam) (in turn

quoting Oregon v. Mathiason, 429 U.S. 492, 495, 97 S. Ct.711, 50 L.

Ed. 2d 714 (1977) (per curiam)). Based on these authorities, this

Court hasdescribed the custody issue as whether a reasonable person

in the accused's circumstanceswould believe that he or she is free

to leave. Cliver v. State, 666 N.E.2d 59, 66 (Ind. 1996). A police

officer's unarticulated plan to arrest or suspicions about a suspect

has no bearingon the issue; rather, “the only relevant inquiry is

how a reasonable man in the suspect'sposition would have understood

his situation.” Stansbury, 511 U.S. at 324 (quotingBerkemer v.

McCarty, 468 U.S. 420, 442, 104 S. Ct. 3138, 82 L. Ed. 2d 317

(1984)).

As to the statements made during the initial

interview with police, the State does notcontest that the police

questioned Dye. Accordingly, the issue turns on whether Dye was

incustody at the time. Dye relies on Loving v. State, 647 N.E.2d

1123 (Ind. 1995), in which this Court reversed a conviction because

the defendant was subjected to custodialinterrogation without being

advised of his Miranda rights. Although the officers in Lovingdid

not consider the defendant a suspect, they never communicated that

belief to him. Moreover, Loving was questioned at the crime scene by

several police officers, thenhandcuffed and placed in the back of a

marked police car to be taken to the police stationwhere he was

questioned without ever being told that he was free to leave. Id. at

1125. ThisCourt held that, “[p]articularly in view of the initial

use of handcuffs, . . . a reasonable personin the defendant's

circumstances would not have believed himself to be free to leave

butwould instead have considered his freedom of movement to have

been restrained to the'degree associated with a formal arrest.'” Id.

at 1126 (quoting Beheler, 463 U.S. at 1125).

Unlike Loving, Dye was told by police that he was

not a suspect and was specificallytold that he was being handcuffed

as a matter of standard procedure during transportation tothe police

station, where the handcuffs were immediately removed as promised.

Bothdetectives testified at the suppression hearing that Dye was

free to leave the interview at anytime, and the totality of the

circumstances surrounding the interview lead us to conclude thata

reasonable person in these circumstances would not have considered

his freedom ofmovement restrained to the degree associated with a

formal arrest. Accordingly, the trialcourt did not err when it

denied Dye's motion to suppress the statements made during

hisinitial interview with police.

The alleged Miranda violation en route to the

blood draw presents issues of bothinterrogation and custody. Here,

the detective's asking Dye what was wrong does not constitute

interrogation under Miranda or the functional equivalent of

questioning underInnis. See Hopkins v. State, 582 N.E.2d 345, 348

(Ind. 1991) (“volunteered statements areadmissible absent Miranda

warnings”); see also Loving, 647 N.E.2d at 1126. Moreover, Dyewas

not in custody at the time the statement was made. The blood draw

was arranged inadvance to take place over Dye's lunch hour, and he

was transported in the front seat of thepolice car without any type

of restraint. The trial court properly denied Dye's motion

tosuppress.

III. Rulings on Challenges for Cause

Dye argues that the trial court improperly

excluded one juror for cause anderroneously denied his motion to

exclude two other jurors for cause. He contends that thisviolated

his “state and federal rights to due process and to an impartial

jury.”See footnote

9

A. Excused for Cause

The trial court excluded for cause one juror who

expressed strong views opposing thedeath penalty. In response to a

question on the jury questionnaire about the circumstancesunder

which he believed the death penalty would be appropriate, the juror

responded “[t]osave society or mankind as a whole when there is no

defense.” The prospective juror furtherexplained this as “[t]he

Hitler argument” and was then questioned at some length by the

trialcourt, State, and defense counsel. The prospective juror stated

during this questioning thathe could recommend the death penalty in

a case of an individual similar to Adolph Hitler and possibly

Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh. However, he later observed

that thiscase involved the alleged killing of three individuals and

agreed that he “could neverconsider” recommending the death penalty

for such a crime. When asked whether he wouldbe able to follow his

oath as a juror and consider the death penalty “as a viable option

in thiscase” he stated that he would not.

1. Juror Exclusion Under the Federal

Constitution

The relevant inquiry for exclusion of jurors for

cause under the federal constitutionis “whether the juror's views

would 'prevent or substantially impair the performance of hisduties

as a juror in accordance with his instructions and his oath.'”

Wainwright v. Witt, 469U.S. 412, 424, 105 S. Ct. 844, 83 L. Ed. 2d

841 (1985) (quoting Adams v. Texas, 448 U.S.38, 45, 100 S. Ct. 2521,

65 L. Ed. 2d 581 (1980)). As the Court explained in Witt, “the

questis for jurors who will conscientiously apply the law and find

the facts. That is what an'impartial' jury consists of . . . .” 469

U.S. at 423. The Witt “standard does not require thata juror's bias

be proved with unmistakable clarity. Deference must be paid to the

trial courtwho was able to see the prospective jurors and listen to

their responses during voir dire.” Underwood v. State, 535 N.E.2d

507, 513 (Ind. 1989).

In Indiana, juries in capital cases are

instructed that they must consider whether theState has proven an

aggravating circumstance beyond a reasonable doubt, and if that is

done,they must then weigh the aggravator(s) against any mitigating

evidence. Jurors who state atthe outset that they will not recommend

a death sentence even if the State proves one or morestatutory

aggravating circumstance are incapable of following the court's

instructions and are accordingly properly excused for cause. The

questioning described above demonstratedthat this prospective

juror's views on the death penalty would have prevented him

fromfollowing the court's instructions and his oath.

Dye contends that it was nevertheless error for

the trial court to excuse the juror forcause because he stated that

he “could consider the death penalty under certain circumstancesand

in fact, believed it to be an appropriate penalty.” As explained

above, the relevantinquiry is not whether the prospective juror

could recommend the death penalty in anyconceivable case, including

genocide or the most famous of mass murders. Rather, the issueis

whether the jury can follow the court's instructions and the juror's

oath in this case.

In most reported cases, excused prospective

jurors have stated blanket opposition tothe death penalty. See, e.g.,

Davis v. State, 598 N.E.2d 1041, 1047 (Ind. 1992) (after beingasked

if there are “any circumstances” under which prospective juror could

vote torecommend the death penalty, juror responded “No sir”);

Benirschke v. State, 577 N.E.2d576, 582-83 (Ind. 1991) (prospective

jurors indicated they were opposed to the death penaltyand “could

not find a case where it would be appropriate”); Underwood, 535 N.E.2d

at 513(prospective juror “candidly expressed several times that she

could not consider the deathpenalty”); Burris v. State, 465 N.E.2d

171, 178 (Ind. 1984) (“all of the excused veniremenstated that under

no circumstances would they consider imposition of the death penalty”).

We find no case from this Court directly addressing the issue Dye

raises. However, severalcases imply that the necessary inquiry is

whether the prospective juror could recommend thedeath penalty in

the case on trial, not in any case. In Davis, 598 N.E.2d at 1047,

the prosecutor asked if a prospective juror could recommend the

death penalty “[u]nder anycircumstances that you can imagine uh, as

have been described to you in this case[.]” Thejuror responded “No”

and this Court upheld the removal for cause under Witt. We

observedthat “[t]here need be no ritualistic adherence to a

requirement that a prospective juror makeit unmistakably clear that

he or she would automatically vote against the imposition of

capitalpunishment.” Id. Similarly, in Daniels v. State, 453 N.E.2d

160, 167 (Ind. 1983), this Courtreviewed the removal for cause of a

prospective juror who, after initially stating he did notbelieve in

the death penalty, stated that he thought it might be warranted in

the case of theassassination of a president. The following colloquy

then took place between the trial courtand the prospective juror:

Q. “Then other than the president you can't think

of any instances or any circumstances involving a murder that you

would feel would warrant recommendationof the death sentence?”

A. “No.”

Q. “And your feelings would preclude you from

recommending the death penalty if the Defendant was found guilty,

is that right?”

A. “Yes, Ma'am.”

Id. at 167. Applying the then-existing federal

constitutional standard of Witherspoon,See footnote

10

this Court upheld the exclusion.

The basic logic of Witt is that it is proper to

excuse jurors who are unable to carry outtheir duties in the case

before them. A juror's willingness to recommend a death

sentenceunder other circumstances is irrelevant to that inquiry.

Because the prospective juror herestated that his views on the death

penalty would render him unable to follow the court'sinstructions

and his oath, exclusion was proper under the federal constitutional

standard ofWitt.

2. Exclusion Under Indiana Code §

35-37-1-5(a)(3)

Most of our death penalty cases have been

resolved under federal constitutionalstandards, presumably because

that was how the issue was framed at trial and on appeal. See, e.g.,

Davis, 598 N.E.2d at 1046-47 (applying Witt); Jackson v. State, 597

N.E.2d 950,961 (Ind. 1992) (applying Witherspoon); Benirschke, 577

N.E.2d at 582-83 (applying Witt);Evans v. State, 563 N.E.2d 1251,

1257 (Ind. 1990) (applying Witherspoon while also quotingthe statute);

Underwood, 535 N.E.2d at 513 (applying Witt). However, Dye also

objectedat trial on the basis of Indiana Code § 35-37-1-5(a)(3),

which provides as one of several“good causes for challenge” that

“[i]f the State is seeking a death sentence, that the

personentertains such conscientious opinions as would preclude the

person from recommending thatthe death penalty be imposed.”

Accordingly, we must address whether the exclusion of thisjuror

violated the statute, which arguably sets a higher bar than Witt.

See generally 16B William Andrew Kerr, Indiana Practice § 21.6d at

151-52 (1998).See footnote

11

Dye suggests that exclusion was improper under

the statute because the prospectivejuror stated that he could

consider the death penalty under some circumstances. The

statutespeaks in terms of preclusion from recommending the death

penalty and does not specificallyaddress whether the preclusion must

be in the particular case only or in all cases, no matterhow far

afield their facts may be from the case at bar.

The prospective juror in Dye's case stated

opposition to the death penalty with a verynarrow exception (Hitler)

that did not apply to Dye's case. The juror went on to explain

hisunequivocal opposition to the death penalty under his limited

knowledge of the facts ofDye's case (the killing of three children).

Although his opinions may not have precluded arecommendation of

death in every hypothetical case, they did preclude a

recommendationof the death penalty in this case. For the same

reasons already explained, we believe this isall that is required

under the statute. Accordingly, because the prospective

juror'sconscientious opinions precluded him from recommending the

death penalty in this case,exclusion was proper under Indiana Code §

35-37-1-5(a)(3).See footnote

12

B. Failure to Excuse for Cause

Dye also argues that the trial court erred by

failing to excuse two prospective jurorsfor cause upon his motion.

Although both of these jurors at some point expressed the viewthat

they would automatically vote to impose the death penalty in the

case of a knowing orintentional murder, their views were tempered by

subsequent questioning. Both jurors weretold that the law required

them to make a recommendation after weighing the aggravatingand

mitigating circumstances. The first juror agreed that there was a

“possibility” that shewould not recommend the death penalty and

agreed she could set aside her personal beliefsand follow the law

and her oath. The other juror also stated that it was “possible”

that hewould vote against the death penalty and agreed that he would

weigh the aggravators andmitigators in good faith and apply the law

as it was given to him.

Dye contends that exclusion for cause was

required by Morgan v. Illinois, 504 U.S.719, 112 S. Ct. 2222, 119 L.

Ed. 2d 492 (1992). In Morgan, the Supreme Court held that thetrial

court's refusal to inquire whether prospective jurors would

automatically vote to imposethe death penalty upon conviction

violated the Due Process Clause of the FourteenthAmendment. However,

in this case the trial court did inquire about the possibility that

thesejurors would vote automatically to impose the death penalty and

defense counsel wereafforded the same opportunity to inquire. This

questioning revealed that these prospectivejurors understood that

both the law and their oath were contrary to their view favoring

anautomatic recommendation of death and agreed that they would

follow the law and their oath. The trial court did not err by

excluding them.See footnote

13

IV. Fair Cross-Section of the Jury Pool

Dye argues that his jury was not selected from a

venire that represented a fair cross-section of the community.

Before trial 150 prospective jurors completed questionnaires

thatincluded a question about race. After reviewing the

questionnaires, Dye discovered that onlyeighteen of the 150

potential jurors identified themselves as African-American.See

footnote

14

He fileda “Motion to Stay

Proceedings or Dismiss the Information Based upon Racial

Discriminationin the Jury Venire” which sought either time to allow

investigation of the racial disparity,supplementation of the venire

pursuant to Indiana Code § 33-4-5-2(d)&(e), or dismissal ofthe

information. The trial court denied the motion.

In order to make a prima facie showing of a

violation of the fair cross-sectionrequirement, a defendant must

establish

(1) that the group alleged to be excluded is a

“distinctive” group in the community;

(2) that the representation of this group in

venires from which juries are selected is not fair and reasonable in

relation to the number of such persons in the community;

and (3) that this underrepresentation is due to

systematic exclusion of the group in the jury-selection process.

Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357, 364, 99 S. Ct.

664, 58 L. Ed. 2d 579 (1979).

Dye acknowledges that he bears the burden of

establishing a Duren violation, see, e.g., Bond v.State, 533 N.E.2d

589, 591 (Ind. 1989), and concedes that he cannot meet the third

prong ofDuren based on the record before us. He nevertheless asserts

error based on the trial court'sdenial of his motion to stay the

proceedings or supplement the venire pursuant to IndianaCode §

33-4-5-2(d)&(e). That statute provides that “[t]he jury

commissioners maysupplement voter registration lists and tax

schedules . . . with names from lists of personsresiding in the

county that the jury commissioners may designate as necessary to

obtain across section of the population of each county

commissioner's district. . . .” Ind. Code § 33-4-5-2(d) (1998). The

supplemental sources “may consist of such lists as those of

utilitycustomers, persons filing income tax returns, motor vehicle

registrations, city directories,telephone directories, and driver's

licenses. . . .” Id. § 33-4-8-2(e). As noted above, Dyemade no

showing that supplementation was necessary to comply with Duren, and

we see nobasis for requiring trial courts under such circumstances

to utilize this discretionary statutoryprovision for supplementation.

The use of voter registration lists complied with

statute. See Ind. Code § 33-4-5-2(1998).See footnote

15

In addition, the trial court also

had a duty to comply the constitutionalrequirements set forth in

Duren, which it did. It was not required to supplement the voter's

registration lists. See Bradley v. State, 649 N.E.2d 100, 103-04

(Ind. 1995) (“Absentconstitutional infirmity, however, we decline to

construe [Indiana Code § 33-4-5-2(d)] so asto convert an option into

a mandate.”). Nor was the trial court required to grant Dye a

stayfor further investigation of systematic exclusion. Dye did not

raise the issue until daysbefore trial when a lengthy continuance

would have been required to conduct the study Dyerequested.See

footnote

16

We review a trial court's denial of

a continuance for an abuse of discretion. Perry v. State, 638 N.E.2d

1236, 1241 (Ind. 1994). Under these circumstances, the denialof

Dye's motion for a stay was not an abuse of discretion.

V. The Clemency Instruction

Dye contends that the trial court erred when it

instructed the jury on clemency. Indiana Code § 35-50-2-9(d)

provides, in relevant part, that “[t]he court shall instruct the

juryconcerning . . . the availability of good time credit and

clemency.”See footnote

17

Dye tendered aninstruction that

provided:

The Governor of Indiana has the power, under

Indiana Constitution, to grant reprieve, commutation, or pardon to a

person convicted and sentenced for murder. The Constitution leaves

it entirely up to the Governor whether and how to use this power.

This power is used sparingly and its imposition, while possible,

should not be considered as a likely result.

Over Dye's objection, the trial court struck the

last sentence of this tendered instruction. Dye argues on appeal

that “what trial counsel sought to do was eliminate speculation

throughcomplete and accurate information about the possibility of

clemency. . . . The speculationthat jury could have entertained is

endless.”See footnote

18

A trial court erroneously refuses a tendered

instruction, or part of a tendered instruction, when: (1) the

instruction correctly sets out the law; (2) evidence supports

thegiving of the instruction; and (3) the substance of the tendered

instruction is not covered bythe other instructions given. Byers v.

State, 709 N.E.2d 1024, 1028-29 (Ind. 1999). The lastsentence of

Dye's tendered instruction fails on both the first and second prongs.

A correct statement of the law regarding clemency

is provided for by the Indiana Constitution and by statute. See

footnote

19

The part of Dye's tendered

instruction that was refused by thetrial court was not a statement

of law at all. Rather, it was a statement of historical

practicesurrounding clemency in Indiana. Moreover, not only is this

language not legal in nature, there is no basis to conclude that it

was correct, if viewed as a prediction of futureGovernors' actions.

Although the exercise of the power to grant clemency may have

beenrare under current and prior Indiana Governors, there is no way

to determine whether afuture Governor may alter this trend of

executive restraint and grant clemency to a significant number of

inmates. See generally Isabel Wilkerson, Clemency Granted to 25

Women Convicted for Assault or Murder, N.Y. Times, Dec. 22, 1990, at

1 (discussing the grant ofclemency by former Ohio Governor Richard

Celeste to women convicted of killing orassaulting husbands or

companions alleged to have physically abused them). The trial

courtdid not err by modifying Dye's tendered instruction on clemency.

VI. Appropriateness of the Death Sentence

As a final point, Dye attacks the appropriateness

of his death sentence. According tostatute, a death sentence is

subject to “automatic review” by this Court. See Ind. Code §

35-50-2-9(j)(1998). Although this Court has the constitutional

authority to review and revisesentences, Ind. Const. art. VII, § 4,

it will not do so unless the sentence imposed is“manifestly

unreasonable in light of the nature of the offense and the character

of theoffender.” Ind. Appellate Rule 17(B). The Court has explained

this standard as “notwhether in our judgment the sentence is

unreasonable, but whether it is clearly, plainly, andobviously so.”

Prowell v. State, 687 N.E.2d 563, 568 (Ind. 1997), cert. denied, ___

U. S.___, 119 S. Ct. 104, 142 L. Ed. 2d 83 (1998)). In reviewing a

death sentence, however, wehave noted that “these harsh requirements

'stand more as guideposts for our appellate reviewthan as immovable

pillars supporting a sentence decision.'” Id. (quoting Spranger v.

State, 498 N.E.2d 931, 947 n.2 (1986)).

Dye contends that the death sentence is not

appropriate when the one aggravating circumstance is weighed against

the mitigating evidence presented, particularly the alleged“residual

doubt” surrounding his guilt. See generally Miller v. State, 702 N.E.2d

1053, 1069(Ind. 1998) (describing “residual doubt” and holding that

the failure to argue it to a jury doesnot constitute ineffective

assistance of counsel). The State alleged as an aggravating

circumstance that Dye killed Celeste after having murdered

Hannah.See footnote

20

See Ind. Code § 35-50-2-9(b)(8)

(1998). Dye offered the testimony of six witnesses at his penalty

phase.See footnote

21

Thejury found that the aggravator

outweighed any mitigators and recommended that the deathpenalty be

imposed. After a sentencing hearing at which Dye presented the

testimony of anadditional witness, the trial court agreedSee

footnote

22

and imposed the death sentence.

The trial court's sentencing order explicitly

rejected Dye's “residual doubt” argument, finding that the evidence

“was more than sufficient to prove beyond a reasonable doubt thatthe

defendant committed the murders with which he was charged. There is

no 'residual doubt' when considering the reasonable doubt standard.”

The trial court's sentencing orderrecounted some of the evidence

against Dye including that his left palmprint was found ona table

near where Hannah was found, that his bloody fingerprint was found

on a garmenttag lying near Hannah's body, and that his semen was

found on a wash cloth found next toher body.

Dye's residual doubt argument on appeal focuses

on a few pieces of unidentified evidence, specifically hairs found

on Hannah's chest, a dried crusty substance found on herthigh and

pubic hair, as well as the absence of Dye's footprints outside the

apartment, theabsence of his fingerprints in the area where he must

have picked up a knife and the absence of fingerprints on the hammer

believed to have been used to bludgeon Hannah and Celeste. He also

points to a fingerprint that was found on a glass in Myrna's

apartment and was compared to twenty people who may have been inside

the apartment (including Dye), but remained unidentified. Defense

counsel was free to argue -- and did argue -- these items tothe jury

in both the guilt and penalty phases and to the trial court at

sentencing. However,in light of the significant physical evidence

that connected Dye to these murders, the jury andtrial court were

not persuaded by these few loose ends. Some of this evidence is

arguably attributable, as the State points out, to the fact that

Myrna's furnished apartment “was afilthy, oft-rented unit with used

carpeting, used furniture and a dirty mattress.” We are no more

persuaded by Dye's residual doubt argument than were the jury and

trial court. Residual doubt presents no basis for reversal here.

As a final point, we observe that Dye points to

no other alleged mitigating circumstances, save his lack of a

significant criminal history found by the trial court. Considering

the nature of the offense and the character of the offender as

presented throughthe proffered mitigating evidence,See footnote

23

we are not persuaded to revise this

sentence.

Conclusion

Walter Dye's convictions for murder and death

sentence are affirmed.

SHEPARD, C.J., and DICKSON and SELBY, JJ., concur.

SULLIVAN, J., concurs with separate opinion.

*****

SULLIVAN, Justice, concurring.

I concur in the Court's opinion. I write to

provide additional review of theappropriateness of the death sentence

imposed here. Cooper v. State, 540 N.E.2d 1216,1218 (Ind. 1989) (“In

contrast to appellate review of prison terms and its

accompanyingstrong presumption that the trial court's sentence is

appropriate, this Court's review of capital cases under article 7 is

part and parcel of the sentencing process. Rather than relyingon the

judgment of the trial court, this Court conducts its own review of the

mitigating andaggravating circumstances 'to examine whether the

sentence of death is appropriate.' . . .The thoroughness and relative

independence of this Court's review is a part of what makesIndiana's

capital punishment statute constitutional.”) (citations omitted).

As to the appropriateness of the death penalty

in this case, the statute guides thisCourt's review by setting forth

standards governing imposition of death sentences. Following

completion of the guilt phase of the trial and the rendering of the

jury's verdict,the trial court reconvenes for the penalty phase.

Before a death sentence can be imposed,our death penalty statute

requires the State to prove beyond a reasonable doubt at least

oneaggravating circumstance listed in subsections (b)(1) through

(b)(12) of the statute. Ind.Code § 35-50-2-9 (Supp. 1996). Here the

State supported its request for the death penaltywith the aggravating

circumstance that Dye committed multiple murders (those of HannahClay

and Celeste Jones), id. § 35-50-2-9(b)(8).

To prove the existence of this aggravating

circumstance at the penalty phase of thetrial, the State relied upon

the evidence from the earlier guilt phase of the trial (with respectto

which the jury had found Dye guilty of the two murders, as well as the

murder ofLawrence Cowherd). The death penalty statute requires that

any mitigating circumstancesbe weighed against any properly proven

aggravating circumstances. The Court's opinion accurately describes

Dye's argument in favor of mitigating circumstances. The juryreturned

a unanimous recommendation that a sentence of death be imposed.

Once the jury has made its recommendation, the

jury is dismissed, and the trial courthas the duty of making the final

sentencing determination. First, the trial court must findthat the

State has proved beyond a reasonable doubt that at least one of the

aggravatingcircumstances listed in the death penalty statute exists.

Ind. Code § 35-50-2-9(k)(1) (Supp.1996). Second, the trial court must

find that any mitigating circumstances that exist areoutweighed by the

aggravating circumstance or circumstances. Id. § 35-50-2-9(k)(2).

Third, before making the final determination of the sentence, the

trial court must considerthe jury's recommendation. Id. §

35-50-2-9(e). The trial court must make a record of itsreasons for

selecting the sentence that it imposes. Id. § 35-38-1-3 (1988).

In imposing the death sentence, the trial court

found that the State proved beyond areasonable doubt a charged

aggravating circumstance listed in the death penalty statute _that Dye

had committed multiple murders. The record and the law supports this

finding.

The trial court found little in the way of

mitigating circumstances to exist. The courtfound only that Dye's

history of prior criminal conduct was not significant (he had

beenconvicted of two Class A misdemeanors _ Driving While License

Suspended in 1989 andBattery in 1992). However, the court did note

that the circumstances surrounding the battery were significant

because the victim of the battery was Myrna Dye. The court

alsoconsidered, but did not find to exist, additional statutory

mitigating circumstances and otherpurported mitigating circumstances

offered by Dye. I agree with the trial court's and thisCourt's

analyses of the mitigation in this case and find the mitigating weight

to be in the lowrange.

As required by our death penalty statute, the

trial court specifically found that theaggravating circumstance

outweighed the mitigating circumstances. The trial court alsogave

consideration to the jury's recommendation. The trial court imposed

the sentence ofdeath.

Based on my review of the record and the law, I

agree that the State has provenbeyond a reasonable doubt an

aggravating circumstance authorized by our death penaltystatute and

that the mitigating circumstances that exist are outweighed by that

aggravatingcircumstance. I conclude that the death penalty is

appropriate for Dye's murder of HannahClay, Celeste Jones and Lawrence

Cowherd III.

*****

Footnotes:

Footnote:

1 Dye testified at trial that, in the course of his sexual

practices with Myrna, he would sometimesejaculate in a washcloth and

had done so the Wednesday before Myrna left him. Myrna testified that,

afterDye had ejaculated on her, she would either take a bath or clean

herself with a washcloth. However, shetestified that her last sexual

contact with Dye was in the early part of June and that she had taken

no dirtywashcloths with her when she moved.

Footnote:

2 “Due process” is a term found in the Fourteenth Amendment of

the U.S. Constitution. It does notappear in the Indiana Constitution.

The closest state analog is the “due course of law” provision in

ArticleI, Section 12. Dye does not cite that provision, let alone

offer a separate analysis based on the stateconstitution. Accordingly,

any state constitutional claim is waived. Valentin v. State, 688 N.E.2d

412(Ind. 1997).

Footnote:

3 Rule 5.3(b) of our Rules of Professional Conduct require that

“[a] lawyer having directsupervisory authority over [a] nonlawyer

shall make reasonable efforts to ensure that the person's conductis

compatible with the professional obligations of the lawyer.” Although

sending a memorandum to theappropriate attorneys is a clerical task

appropriately assigned to a paralegal, the prosecutors assigned to

acase nevertheless bear the ultimate burden of ensuring compliance

with the discovery rules. This isespecially true under the

circumstances here, where a deputy prosecutor knew of -- indeed,

requested thatdetectives take -- an important statement from a crucial

witness. That this is a death penalty case onlyheightens the need for

attorneys within the prosecutor's office to ensure that paralegals are

turning over alldiscovery in a timely manner.

Footnote:

4 Dye also suggests that he was misled by some answers given by

State's witnesses during pretrialdepositions. However, he does not

contend that these answers were not correct according to the

witness'sknowledge at the time of their respective depositions.

Moreover, Dye had the opportunity to re-deposethese witnesses before

trial, in light of the information belatedly disclosed to him on

August 13. Thispresents no basis for reversal.

Footnote:

5 Dye also mentions evidence of shoeprints but then notes that

the trial court excluded thisevidence. Accordingly, any belated

disclosure of this evidence presents no basis for reversal.

Footnote:

6 The State does not assert waiver but instead addresses the

issue on its merits, pointing out thatthree of the witnesses mentioned

in the motion were not called at trial by the State, the complained

ofportion of another witness's testimony was not presented at trial,

an expert's report was timely disclosed,an amended transcript of a

witness's statement was issued merely to correct “inaudibles” from an

earliertranscript, and Dye learned of the oral statements of two other

witnesses more than a week in advance oftrial which was sufficient

time to render them nonprejudicial to his case.

Footnote:

7 Dye captions his argument in terms of “state and federal rights

self-incrimination and to counsel”but merely cites Article I, Sections

11-13 without making any separate analysis based on the

stateconstitution. Any claim of error under the Indiana Constitution

is waived. See Valentin v. State, 688N.E.2d 412 (Ind. 1997).

Footnote:

8 After this interview with police, Dye spent several more hours

with police but points to nostatements made during this time that

should be suppressed. Accordingly, we need not address whether

anycustodial interrogation occurred subsequent to the initial

interview described above.

Footnote:

9 Once again, any state constitutional claim is waived for the

failure to make a separate argumentunder the Indiana Constitution. See

supra notes 2 and 7.

Footnote:

10 See Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510, 88 S. Ct. 1770, 20

L. Ed. 2d 776 (1968). TheWitherspoon standard, as commonly applied at

the time, permitted excusing only those jurors who make“unmistakably

clear (1) that they would automatically vote against the imposition of

capital punishmentwithout regard to any evidence that might be

developed at the trial of the case before them, or (2) that

theirattitude toward the death penalty would prevent them from making

an impartial decision as to thedefendant's guilt .” Id. at 522 n.21 (emphasis

in original). In Witt, the Supreme Court made clear that theCourt's

holding in Witherspoon “focused only on circumstances under which

prospective jurors could not be excluded; under Witherspoon's facts it

was unnecessary to decide when they could be.” Witt, 469 U.S.at 422 (emphasis

in original). Witt concluded that the quoted footnote language from

Witherspoon was“dicta” and “not controlling.” Id.

Footnote:

11 Dye contends that this statute is a codification of the

standard set forth by the United StatesSupreme Court in Witherspoon.

This is incorrect. Although the statutory language is somewhat similar

toWitherspoon, the statutory provision has been on the books in a

virtually identical form for over a century -- long before Witherspoon.

See Kerr, supra § 21.6d, at 149 n.42.

Footnote:

12 Dye quotes the following language from this Court's opinion in

Baird v. State, 604 N.E.2d 1170,1185 (Ind. 1992), “[o]nly jurors who

state, without equivocation or self-contradiction, that they would

notvote for death in any case can be excluded . . . .” Baird cites

Witherspoon and Lamar v. State, 266 Ind.689, 366 N.E.2d 652 (1977), an

Indiana case applying Witherspoon, as support. Baird does not cite

thestatute, and Lamar cites the statute without quoting the language

of subsection (3). Lamar instead citesand applies Witherspoon. As

explained above, the federal constitutional standard of Witherspoon

has beenreplaced by Witt. Moreover, Baird did not purport to be

interpreting the statute.

Footnote:

13 As the State points out, even if a trial court erroneously

refuses to remove for cause jurors whodeclare that they will vote to

impose death automatically, a death sentence may be affirmed if the

jurorswere nevertheless removed through the use of peremptory

challenges. See Ross v. Oklahoma, 487 U.S. 81,108 S. Ct. 2273, 101 L.

Ed. 2d 80 (1988). The relevant inquiry is whether any such jurors sat

on the jurywhich ultimately sentenced the defendant to death. Id. at

85-86. In Dye's case, both jurors were excusedthrough the use of

peremptory challenges and he does not contend that the use of these

challenges preventedhim from excusing other prospective jurors who

would have voted to impose death automatically.

Footnote:

14 It was later revealed during voir dire that one of the

eighteen was mentally handicapped and haderroneously listed her race

as African-American.

Footnote:

15 In addition, this Court has expressed approval of the use of

voter registration lists from which toselect a pool of prospective

jurors. See, e.g., Fields v. State, 679 N.E.2d 1315, 1318 (Ind. 1997);

Bradleyv. State, 649 N.E.2d 100, 104-05 (Ind. 1995); Concepcion v.

State, 567 N.E.2d 784, 788 (Ind. 1991)(citing Burgans v. State, 500

N.E.2d 183 (Ind. 1986)); Smith v. State, 475 N.E.2d 1139, 1142-43

(Ind.1985).

Footnote:

16 In his reply brief, Dye asks that this Court take judicial

notice of the results of a not-yet-completed study in a pending

capital case that examines the possible systematic exclusion of

AfricanAmericans from jury venires in Marion County. Evidence Rule

201(a) permits courts to take judicialnotice of a fact that is “not

subject to reasonable dispute in that it is either (1) generally known

within theterritorial jurisdiction of the trial court, or (2) capable

of accurate and ready determination by resort tosources whose accuracy

cannot reasonably be questioned.” The study alluded to here is not a

propersubject of judicial notice. According to the limited information

in the reply brief, the study has taken weeksor months and a similar

study has never before been done. Its subject matter is neither

“generally known”within the jurisdiction nor do the conclusions of

such a study seem to be “capable of accurate and readydetermination”

by resort to sources that cannot be reasonably questioned.

Footnote:

17 This language was added to the statute in 1993. See Pub. L.

250-1993, § 2, 1993 Ind. Acts4481.

Footnote:

18 Dye concedes that giving an instruction that tells the jury

that the governor has the power tocommute a sentence does not violate

the Eighth Amendment, applicable to the states through the

FourteenthAmendment. See California v. Ramos, 463 U.S. 992, 103 S. Ct.

3446, 77 L. Ed. 2d 1171 (1983).

Footnote:

19 “The Governor may grant reprieves, commutations, and pardons,

after conviction, for alloffenses except treason and cases of

impeachment, subject to such regulations as may be provided by law.”

Ind. Const. art. V, § 17. Such applications are to be filed with the

parole board, which shall make arecommendation to the Governor after

(1) notifying (A) the sentencing court, (B) the victim of the crime

ornext of kin, and (C) the prosecuting attorney for the county where

the conviction was obtained and (2)conducting an investigation and (3)

hearing. Ind. Code § 11-9-2-1 to -2 (1998).

Footnote:

20 The State also alleged, on a separate charging instrument

filed on the same day, that Dye killedLawrence after murdering Hannah.

However, the jury was not presented with this second

aggravatingcircumstance nor did the trial court make any mention of it

in its sentencing statement or sentencing order.

Footnote:

21 A Marion County probation officer testified that Dye was

compliant during his probationarysentence for a Class A misdemeanor

battery offense against Myrna. “He did what he was supposed to do. He

finished his counseling and he paid his money and he kept his

appointments.” Dr. Odie Bracy, III, aclinical neuropsychologist,

testified that overall Dye “presented fairly normally. . . . [H]e was

verycooperative, very friendly, presented no problems whatsoever

during the entire day. . . . He showed a goodcapability to learn, to

comprehend, to follow instructions, and exhibited an excellent memory.”

ThreeMarion County corrections' officers testified that they had never

had any problems with Dye during hispretrial incarceration. Finally, a

public information officer from the Department of Correction testified

that186 of the 1536 men serving sentences in the general prison

population for murder were convicted ofmultiple killings. She

testified that twenty-seven of the fifty men on death row were there

for multiplemurders. On cross-examination the witness testified that

multiple murder means two or more and that shedid not have the

statistics for those who committed three murders.

Footnote:

22 The trial court found that the State had proven the

aggravating circumstance beyond areasonable doubt and found as a

mitigating circumstance that “[a]lthough he defendant's history of

priorcriminal conduct cannot be considered significant, the

circumstances surrounding [his] battery conviction[against Myrna in

1992 was] significant.”

Footnote:

23 Dye contends that the evidence “presented to the jury

primarily painted [him] as an average Joewith no serious

psychopathology.” He points to his stable work history, compliance

with probation termsand corrections officers while awaiting trial, his

brother's testimony that he was not capable of the killings,and a

letter from his daughter telling him that she missed and loved him.

However, Dye points to only onepotentially mitigating circumstance

alleged to have been overlooked by the trial court based on

thisevidence. Citing Skipper v. South Carolina, 476 U.S. 1, 106 S. Ct.

1699, 90 L. Ed. 2d 1 (1986), hecontends that the trial court

apparently overlooked the testimony from corrections officers about

hiscompliant behavior because “it does not appear in [the] sentencing

order.” In Skipper, the Supreme Courtheld that it was error for a

state trial court to exclude the testimony of jailers and a “'regular

visitor' to thejail to the effect that petitioner had 'made a good

adjustment' during his time spent in jail.” Id. at 3. TheCourt

observed that the exclusion of this “relevant mitigating evidence

impeded the sentencing jury's abilityto carry out its task of

considering all relevant facets of the character and record of the

individualoffender.” Id. at 8. Unlike Skipper's jury, Dye's jury heard

this testimony and nevertheless recommendedthat death be imposed.

Skipper presents no basis for reversal here.