100 F.3d 750

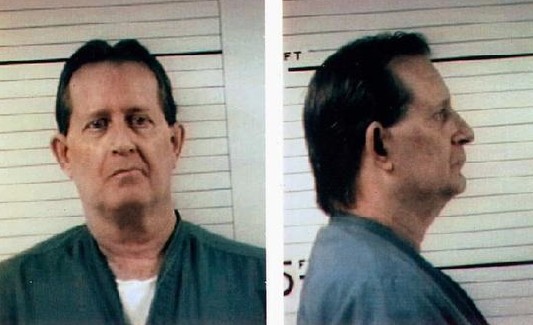

Gary Lee

Davis, Petitioner-Appellant,

v.

Executive Director of Department of Corrections, as Head of

the Department of Corrections, Ari Zavaras, Respondent-Appellee.

No. 95-1285

Federal Circuits, 10th

Cir.

December 23, 1996

Appeal from the United States District

Court for the District of Colorado, (D.C. NO. 94-Z-1931) Vicki

Mandell-King, Assistant Federal Public Defender, Denver, CO;

and Dennis W. Hartley, Colorado Springs, CO (Michael G. Katz,

Federal Public Defender, Denver, CO, with them on the briefs),

for Petitioner-Appellant.

Robert M. Petrusak, Senior Assistant

Attorney General, Denver, CO; and Steven Bernard, Adams County

Attorney's Office, Brighton, CO (Gale A. Norton Attorney

General, with them on the brief) for Respondent-Appellee.

Before ANDERSON, BALDOCK, and HENRY,

Circuit Judges.

STEPHEN H. ANDERSON, Circuit Judge.

Gary Lee Davis appeals from the district

court's denial of his first petition for a writ of habeas

corpus, in which he seeks to overturn his sentence of death.

We granted Mr. Davis's request for a certificate of probable

cause and a stay pending appeal.

We hold as follows: (1) Mr. Davis was not abandoned by his

attorney in the closing argument of the penalty phase of his

trial; (2) Mr. Davis suffered no prejudice from his attorney's

failure to pursue and present certain additional mitigating

evidence in the penalty phase; (3) the statutory aggravators

presented to the jury were either valid or, if invalid or

otherwise erroneously submitted to the jury, were harmless;

(4) the penalty phase jury instructions neither misled nor

confused the jury concerning its evaluation of mitigating

evidence; and (5) no error occurred in the removal for cause

of three prospective jurors. We therefore affirm the denial of

Mr. Davis's habeas petition.

BACKGROUND

In July 1986, in Byers, Colorado, Gary

Davis and his then-wife, Rebecca Fincham Davis, kidnaped,

sexually assaulted and murdered Virginia May. Mr. Davis has

never challenged his conviction for that crime, nor does he

dispute his involvement in it. The tragic facts concerning

this crime have been fully set out in the state court opinions

affirming Mr. Davis's conviction and sentence on direct appeal

and in state post-conviction proceedings. People v. Davis, 849

P.2d 857 (Colo. Ct. App. 1992) (Davis II), aff'd, 871 P.2d 769

(Colo. 1994) (Davis III); People v. Davis, 794 P.2d 159 (Colo.

1990) (Davis I), cert. denied,

498 U.S. 1018 (1991). We refer to facts

concerning the crime only as necessary in our discussion of

particular issues.

Mr. Davis and Ms. Fincham were tried

separately. The state sought the death penalty against Mr.

Davis but not Ms. Fincham. When Mr. Davis's appointed state

public defender had to withdraw because of a conflict of

interest, Craig Truman was appointed Mr. Davis's counsel.

Against Mr. Truman's advice, Mr. Davis testified before the

jury during the guilt/innocence phase of the trial, stating

that he had kidnaped, assaulted and murdered Ms. May, and

emphasizing his own culpability over that of Ms. Fincham. The

jury found Mr. Davis guilty of murder in the first degree

after deliberation; felony murder; conspiracy to commit murder

in the first degree; second degree kidnaping; and conspiracy

to commit second degree kidnaping. He was sentenced to life

imprisonment on the conspiracy and second degree kidnaping

convictions.

The penalty phase for the murder

convictions began the day after the guilt/innocence phase

concluded. The jury was presented with six aggravating factors

and eight mitigating factors. It found all six aggravating

circumstances proven and made no findings on the existence of

any mitigating factors. The jury concluded beyond a reasonable

doubt that death was the proper punishment.

In his direct appeal, Mr. Davis challenged

his sentence on numerous grounds. The Colorado Supreme Court

affirmed the sentence, with three justices dissenting. Davis

I. Mr. Davis then filed a motion for post-conviction relief,

arguing that Mr. Truman provided ineffective assistance of

counsel during the penalty phase of the trial. Mr. Davis

sought additional time to investigate this claim of

ineffectiveness. The court conducted a hearing, after which it

denied his ineffectiveness claim. The Colorado Court of

Criminal Appeals affirmed, with one judge dissenting, Davis II,

and the Colorado Supreme Court affirmed. Davis

III.

After exhausting state remedies, Mr. Davis

brought this federal habeas petition arguing: (1) Mr. Truman

rendered ineffective assistance of counsel during the penalty

phase because he (a) abandoned Mr. Davis in his closing

argument; and (b) failed to conduct adequate investigation

into, and failed to present, mitigating evidence in Mr.

Davis's background; (2) the jury was permitted to consider

unconstitutional statutory aggravators; (3) various errors

occurred in the penalty phase instructions; and (4) the trial

court erroneously excluded three prospective jurors because of

their stated qualms about the death penalty. The district

court denied his habeas petition. Davis v. Executive Dir., 891

F. Supp. 1459 (D. Colo. 1995). Mr. Davis appeals.

DISCUSSION

We review de novo the district court's

legal conclusions in dismissing a petition for a writ of

habeas corpus. Harvey v. Shillinger, 76 F.3d 1528, 1532 (10th

Cir. 1996), cert. denied, ___ U.S. ___, 117 S.Ct. 253, 136

L.Ed.2d 179 (1996). We review the district court's factual

findings for clear error. Edens v. Hannigan, 87 F.3d 1109,

1113-14 (10th Cir. 1996). State court factual findings are

presumptively correct and are therefore entitled to deference.

Medina v. Barnes, 71 F.3d 363, 369 (10th Cir. 1995); 28 U.S.C.

Section(s) 2254(d).

I. Effective Assistance of Counsel.

A. Abandonment:

Mr. Davis first argues that his attorney,

Mr. Truman, effectively abandoned him during closing arguments

in the penalty phase of his trial, thereby leaving him without

counsel at all. The obligation to provide effective assistance

of counsel extends to a capital sentencing hearing. Brecheen

v. Reynolds, 41 F.3d 1343, 1365 (10th Cir. 1994), cert. denied,

_____ U.S. _____, 115 S. Ct. 2564, 132 L.Ed.2d 817 (1995). "A

defense attorney who abandons his duty of loyalty to his

client and effectively joins the state in an effort to attain

a conviction or death sentence suffers from an obvious

conflict of interest," and thereby fails to provide effective

assistance. Osborn v. Shillinger, 861 F.2d 612, 629 (10th Cir.

1988).

Usually, when a defendant claims

ineffective assistance of counsel because his attorney's

performance was inadequate, he must show both constitutionally

deficient performance and that he was prejudiced by his

attorney's errors. Brecheen, 41 F.3d at 1365. In the event of

an actual conflict of interest occasioned by abandonment,

prejudice is presumed. Osborn, 861 F.2d at 626; see also

United States v. Williamson, 53 F.3d 1500, 1510-11 (10th

Cir.), cert. denied, _____ U.S. _____, 116 S. Ct. 218, 133

L.Ed.2d 149 (1995); Brecheen, 41 F.3d at 1364 n.17.

Mr. Truman began his closing argument in

the penalty phase with the following:

Now it's my turn to come and ask you for

Gary Davis's life. That's what I'm here to do. For 14 long

years I have practiced law in these criminal courts and up and

down these mean halls. You think you have seen just about

everything. You think you have seen everything once. I have

never seen a case like this. I never have, and I hopefully

never will.

R. Vol. V, Vol. 33 at 51. He went on to

state:

There are times in this case that I hate

Gary Davis, I am going to tell you that, and I think you know

it. There are times I hate the things that he has done, and I

have told him, and I tell you, there's no excuse for it.

There's no excuse for it whatsoever.

In the times that we have seen these cases

come and go, they get worse and worse instead of better, and

I'm not kidding anybody, this is one of the worst ones I have

ever seen or heard of. I can't recall a case where I have

never made a closing argument, and I can't recall a case where

we have spoken as little to you as we have this one, and

there's a reason for it. That reason is that in December, when

I first saw Gary Davis, I knew that sometime or other I was

going to be standing here asking for 12 people's mercy. That's

all he has got. That's all we can seek. . . . I, too, think

killing is wrong, and it's killing, whether it's the state,

and it's killing, whether it's Gary Davis. . . . It says, "Thou

shalt not kill," and if I or you . . . or anybody who was

there, and if Ginny May would have lived -- she didn't, she

died -- and if I thought -- if I thought that Brandon and

Krista May would have five seconds of peace by Gary Davis's

death, I would choke the life out of him right now, and he

knows it, but it won't help. . . .

Some of the times I hate Gary Davis is

because of what he has done to me. I have been on this case

since December, when the public defender got off. The public

defender got off because of Gary Davis's lies, and Gary Davis

has lied to me. Gary Davis set up the public defender for

failure. In a lot of respects he set me up for failure. I

guess I'm too prideful, worried about my reputation. Maybe

that's why I hated him the other day.

Id. at 51-53. Mr. Truman then discussed at

some length the relationship between Mr. Davis and Ms. Fincham,

reiterating the theme of the guilt/innocence phase of the

trial, that Ms. Fincham was the more culpable of the two. Mr.

Truman told the jury:

As bad as Gary Davis is -- and you won't

hear me say otherwise -- there's someone equally as bad, maybe

worse. That someone continues to lie. . . . Anything to save

Becky Davis [Fincham]. That demonstration alone, of watching

him testify, I submit to you shows who's wearing the pants in

this family. I'm not saying that forgives Gary Davis. Nothing

forgives Gary Davis. He deserves to get what she got. Sauce

for the goose is sauce for the gander. They're in the same

position, I submit to you, and I submit to you that both ought

either to look at the gas chamber, or both ought to spend the

rest of their lives in the penitentiary.

Id. at 55. He concluded with the following:

I have never had a case like this before,

and I have never been able not to talk to juries, as I almost

wasn't able to talk to you at the start. I guess I'm a

prideful man. I have been doing this a long time and I think

I'm good at it, and I haven't said anything during this trial

and I have watched you, some of you looking at me, wondering,

when are you going to get started? When are you going to start

representing your client? When are you going to get up? I have

seen that in your eyes. I know what you mean. You can't change

what's happened and I am not going to twist or fudge anything

for you. Now's the time for me to be heard. Now's the time I'm

talking to you, and each one of you has it in your hand to

spare Gary Davis or to kill him, for if one of you says no,

stop the killing, there's been too much, that's the way it

will be. And if all of you believe that the only thing for

Gary Davis is to put him in the gas chamber, drop those

pellets into the cyanide bath, watch him choke to death,

that's what will happen.

Is there a man so bad that he's

irredeemable? That's the question here. There's no question

about what happened. It's a question about what's going to

happen. I have never begged a jury before for anything, but

I'm begging you now, and I am asking you please not to kill

Gary Davis.

Id. at 56.

Mr. Davis relies heavily on our decision in

Osborn, calling this case "virtually indistinguishable" from

Osborn, in which we held that the defendant's attorney at the

sentencing hearing "so abandoned" his duty to advocate on

behalf of his client "that the state proceedings were almost

totally non-adversarial." Osborn, 861 F.2d at 628. Among the

statements and actions upon which we based that conclusion

were the following: "Osborn's counsel made statements to the

press indicating that Osborn had no evidence to support his

claims" and "although counsel knew or should have known that

the prosecutor's office had conveyed ex parte information to

the sentencing court, counsel never sought to discover its

contents or counteract its effect." Id. Moreover, the district

court described the attorney's arguments at the sentencing

phase as follows:

Counsel's arguments at the sentencing

hearing stressed the brutality of the crimes and the

difficulty his client had presented to him. At the beginning

of the hearing, counsel referred to the difficulty of

presenting mitigating circumstances when evidence against a

client is overwhelming. In closing, counsel referred to the

problems Osborn's behavior had created for counsel throughout

the representation. Counsel described the crimes as horrendous.

He analogized his client and the co-defendants to "sharks

feeding in the ocean in a frenzy; something that's just animal

in all aspects."

Id. (quoting Osborn v. Shillinger, 639 F.

Supp. 610, 617 (D. Wyo. 1986), aff'd, 861 F.2d 612 (10th Cir.

1988)). We concluded that Osborn's attorney did more than "make

poor strategic choices;" rather, "he acted with reckless

disregard for his client's best interests and, at times,

apparently with the intention to weaken his client's case." Id.

at 629.

In our view, Mr. Truman's closing argument

did not constitute abandonment of Mr. Davis, such that the

adversarial process was undermined.

As the district court observed, Mr. Truman was placed in a

very difficult position because of Mr. Davis's own decision,

against Mr. Truman's advice, to testify at the end of the

guilt/innocence phase of the trial and take full

responsibility for the crime, contrary to the strategy,

pursued up to that point, of portraying Mr. Davis as less

culpable than Ms. Fincham. That testimony made it even more

difficult to explain why Mr. Davis did not deserve the death

penalty, while maintaining credibility with the jury.

Moreover, while Mr. Truman expressed in

general terms how horrible the case was -- "one of the worst

ones I have ever seen" -- and expressed his hatred of Mr.

Davis and his crimes, that is significantly different from "stress[ing]

the brutality of the crimes . . . . describ[ing] the crimes as

horrendous . . . [and] analogiz[ing] his client and the co-defendants

to `sharks feeding in the ocean in a frenzy; something that's

just animal in all aspects.'" Osborn, 861 F.2d at 628 (quoting

Osborn, 639 F. Supp. at 617)). Mr. Davis has never disputed

that he participated in a crime which was undeniably horrific.

Mr. Truman's statements about Mr. Davis's

lies, to him and to others, while blunt and unflattering to Mr.

Davis, were in part a response to Mr. Davis's decision to

testify. His testimony itself, which completely undermined the

strategy pursued by Mr. Truman, with Mr. Davis's apparent

approval, revealed the obvious: that Mr. Davis had been at

least deceptive towards Mr. Truman. Mr. Truman's remarks were

at least an attempt to cast doubt on the veracity of Mr. Davis,

who had just testified in a manner virtually guaranteed to

condemn him to a sentence of death.

Furthermore, a substantial portion of the

closing argument was devoted to stressing the deceptiveness of

Ms. Fincham and her control over Mr. Davis, and suggesting

that Mr. Davis's testimony accepting full responsibility for

the crime was yet another example of that control. Mr. Truman

emphasized that Mr. Davis should receive the same sentence as

Ms. Fincham, who had been sentenced to life imprisonment. This

was a reiteration of the "equal justice" defense pursued

throughout the trial, but substantially undermined by Mr.

Davis's testimony. That had always been the most viable

strategy for Mr. Davis to avoid the death penalty, and Mr.

Truman effectively pursued it again in closing argument.

Finally, Mr. Truman closed his argument

with a plea for Mr. Davis's life: "I have never begged a jury

before for anything, but I'm begging you now, and I am asking

you please not to kill Gary Davis." R. Vol. V, Vol. 33 at 56.

That was a powerful plea, coming from a man who had just

expressed his own dislike of Mr. Davis and his crime.

In sum, this case is distinguishable from

Osborn, both because the actual closing argument in this case

was qualitatively different and because the circumstances of

this case left Mr. Truman with little room to maneuver. We

therefore hold that Mr. Davis was not abandoned by Mr. Truman

in his closing argument.

B. Presentation of Mitigating Evidence:

Mr. Davis also argues that Mr. Truman was

ineffective in failing to adequately investigate potential

evidence in mitigation and in failing to present certain

mitigating evidence which was available. To establish

ineffective assistance of counsel, a defendant "must first

show that counsel `committed serious errors in light of "prevailing

professional norms"' in that the representation fell below an

objective standard of reasonableness." Brecheen, 41 F.3d at

1365. See Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 688 (1984).

There is a "strong presumption" that counsel has acted

reasonably and represented his client effectively. Id. at 689.

We review an attorney's performance with substantial deference.

Id.; see also Brecheen, 41 F.3d at 1365; Stafford v. Saffle,

34 F.3d 1557, 1562 (10th Cir. 1994), cert. denied, 115 S. Ct.

1830 (1995).

Once a defendant has shown constitutionally

deficient performance, he must demonstrate prejudice from that

performance. The defendant bears the burden of proving both

deficient performance and prejudice. Brecheen, 41 F.3d at

1365. We review an ineffectiveness claim de novo, as it

presents a mixed question of law and fact. Brewer v. Reynolds,

51 F.3d 1519, 1523 (10th Cir. 1995), cert. denied, _____ U.S.

_____, 116 S. Ct. 936, 133 L.Ed.2d 862 (1996).

We review the district court's factual

findings for clear error. Id. In some cases, we proceed

directly to the issue of prejudice: "[t]he Supreme Court has

observed that often it may be easier to dispose of an

ineffectiveness claim for lack of prejudice than to determine

whether the alleged errors were legally deficient." United

States v. Haddock, 12 F.3d 950, 955 (10th Cir. 1993); see also

Strickland, 466 U.S. at 697; Brewer, 51 F.3d at 1523; United

States v. Smith, 10 F.3d 724, 728 (10th Cir. 1993). This is

such a case. We accordingly express no opinion on whether Mr.

Truman's performance was deficient.

To establish prejudice under Strickland, Mr.

Davis must show there exists "a reasonable probability that,

but for counsel's unprofessional errors, the result of the

proceeding would have been different. A reasonable probability

is a probability sufficient to undermine confidence in the

outcome." Strickland, 466 U.S. at 694; Brewer, 51 F.3d at

1523.

As applied to the penalty phase of a

capital case, a petitioner alleging prejudice from counsel's

ineffectiveness must show "a reasonable probability that,

absent the errors, the sentencer -- including an appellate

court, to the extent it independently reweighs the evidence --

would have concluded that the balance of aggravating and

mitigating circumstances did not warrant death." Strickland,

466 U.S. at 695. We must "keep in mind the strength of the

government's case and the aggravating factors the jury found

as well as the mitigating factors that might have been

presented." Stafford, 34 F.3d at 1564; see also Brewer, 51

F.3d at 1523.

Mr. Davis's specific allegations of error

are that Mr. Truman: (1) failed to contact to solicit

information and possible testimony from family members,

including Tonya Tatem, Mr. Davis's first wife; Glenn Davis, a

stepbrother; Adeline Davis, Mr. Davis's mother; and Mr.

Davis's children and stepchildren; (2) failed to follow up and

pursue initial cursory contacts with Mr. Davis's brother,

Wayne Gehrer, and with Mr. Davis's second wife, Leona Coates;

(3) failed to adequately investigate and present expert

testimony on Mr. Davis's alcoholism; (4) failed to explore Ms.

Fincham's psyche, personality and background, including

contacting her first husband, Charles Ledbetter, and

presenting expert testimony from Dr. Chris Hatcher, a

psychologist who was an expert on relative accomplice

liability; (5) failed to contact and adequately develop

possible testimony from former employers and acquaintances,

including people who lived in the same apartment complex as

the Davises; and (6) failed to present favorable prison

records from which mitigating evidence might have been derived.

Mr. Davis argues that, had the jury heard all of this evidence,

it would have viewed him in a different light and probably

sentenced him to life imprisonment rather than death.

1. Family Members:

Mr. Davis argues Mr. Truman failed to

follow up on initial contacts with Mr. Davis's brother, Wayne

Gehrer, and with Mr. Davis's second wife, Leona Coates, as

well as failing to contact at all his first wife, Tonya Tatem,

his children and stepchildren, his stepbrother, and his mother.

Investigator William Martinez had prepared a report for Mr.

Truman's office, detailing his investigation, conducted in

July 1986, into Mr. Davis's background. It includes a

description of a conversation with Wayne Gehrer, in which Mr.

Gehrer described Mr. Davis as "always a little bit different,

devil-may-care type attitude, always had an alcohol problem."

R. Vol. II, Doc. 54, tab 20.

Mr. Martinez's report indicates "[w]hen

asked how he felt about the homicide and about Gary and what

he thought of it, his (almost quote) words were -- it was the

inevitable conclusion to his life's story." Id. That

assessment of Mr. Davis was not likely to be viewed by the

jury as mitigatory; rather, it suggests he was a reckless and

irresponsible man, whose life story was appropriately

concluded by the tragic murder of Ms. May. Further discussion

with Mr. Gehrer was likely to produce evidence at least as

damaging, perhaps more so, than helpful to Mr. Davis. Mr.

Davis thus suffered no prejudice from Mr. Truman's failure to

call Wayne Gehrer to testify in the penalty phase of the trial.

Mr. Davis similarly challenges Mr. Truman's

failure to pursue Leona Coates as a possible mitigation

witness. At the time of Mr. Davis's trial, she had been

interviewed by another investigator, Sherry Garner, to whom Ms.

Coates stated that Mr. Davis had a drinking problem and that

there "were times that he was violent with [her.]" Statement

of Leona Coates dated 8/7/86, R. Vol. VI. Additionally, she

stated that Mr. Davis pointed a rifle at her head one time,

and tried to choke her twice. Id.

When she testified, nine years later, in Mr.

Davis's habeas proceeding, she stated that Mr. Davis was never

violent towards her, that the gun to which she referred in

1986 was a plastic gun, and that she was "under a lot of

pressure" in 1986 when she gave the statement about the gun

being held to her head. R. Vol. X at 88. The district court

described that testimony as "equivocal and contradictory with

previous statements given to the police at the time of Davis'

arrest." Davis, 891 F. Supp. at 1468.

The court further observed that Ms. Coates

was "not clear that she would have made herself available to

testify at the trial because she had moved out of state in

order to protect her children from the publicity." Id. Given

the damaging nature of her statements about Mr. Davis in 1986,

as well as the uncertainty as to whether she would even have

been available to testify, we see no prejudice to Mr. Davis

from Mr. Truman's failure to call her as a mitigation witness.

Mr. Davis also argues he suffered prejudice

from the failure to procure testimony from Tonya Tatem, his

children and stepchildren, his mother, and a stepbrother. He

argues they would have testified about his troubled childhood,

his passivity and tendency to be a follower, his devotion to

his children, and his recurrent problems with alcohol.

The district court responded to this

argument as follows: "[p]resenting testimony from family,

friends, or other associates could have invited inquiry by the

prosecution into Davis' history of violence towards his former

wives, his vengeful motives behind the sexual assault of an

adolescent girl, his general dishonesty and his sexual

exploitativeness." Davis, 891 F. Supp. at 1467.

For the following reasons, we agree with the district court

that such testimony was as likely to open the door to damaging

evidence as it was to helpful evidence.

Tonya Tatem's affidavit and deposition

testimony both described Mr. Davis as a loving and good

husband, when he was not drinking. Both also described him as

increasingly abusive when drinking. Again, the potentially

positive effect of such testimony on the jury is offset by the

potentially negative effect of a description of a man who

routinely became abusive towards his spouse when drinking, and

whose drinking ultimately destroyed their marriage.

Various of Mr. Davis's children and

stepchildren testified, either at the habeas hearing or by way

of affidavit. Their testimony recalled vague general childhood

memories of Mr. Davis as a loving father, as well as more

detailed accounts of how he has reestablished his relationship

with them since his imprisonment for the murder of Ms. May,

and how he is currently helping them. The district court

described the direct testimony of three of Mr. Davis's

children as follows:

Davis' three children would have had very

little to offer at the trial. Although they each testified as

to how important Davis was to them now, they could offer

little testimony about the kind of father he had been. Davis

spent four of the five years prior to the murder of Virginia

May in prison. He did not see his children between the time he

was released from prison and he was arrested for the murder.

The only "fatherly" story that each child was able to relate

was a well rehearsed anecdote about a family fishing trip

which probably occurred before the two youngest children would

have had any conscious memories.

Id. at 1468. We agree with the district

court's characterization of that testimony, noting that the

district court, not we, was in the position to evaluate the

credibility of those witnesses. Their testimony about Mr.

Davis, both at the hearing and by way of affidavit, concerning

his character prior to and at the time of the murder was, of

necessity, vague and non-specific, simply because they were

either fairly young and/or Mr. Davis had spent little time

with them. Their testimony about their relationship with him

now, and since his conviction and sentence for the May murder,

is less significant. We conclude that such testimony would

have had very little impact on the jury in this case.

Finally, Mr. Davis argues that Mr. Truman

should have presented testimony from Glenn Davis, the

stepbrother to whom Mr. Davis was closest, as well as from Mr.

Davis's mother. Glenn Davis's deposition portrays Mr. Davis as

a passive follower, but concedes that, if drunk, he might be

capable of committing a crime like the murder of Ms. May: "I

will say that for him to do that he had to be drunk. . . . [I]f

he was sober and wasn't drinking that night, in my belief I

don't think Gary would have gone along with it." Glenn Davis

Dep. at 24, R. Vol. IX.

Mr. Davis's mother, Adeline Davis, was not

contacted for possible testimony at the time of Mr. Davis's

trial, partially because Wayne Gehrer told Investigator

Martinez that Mr. Davis's parents were experiencing poor

health, and he worried that contacting them to testify on

their son's behalf might worsen their health. Adeline Davis's

deposition confirms that she was experiencing severe health

problems in 1986 and 1987.

Additionally, Mr. Truman testified, at the

hearing on the Rule 35(c) motion, that he was aware that after

Mr. Davis's conviction and imprisonment for first-degree

sexual assault of the 15-year-old, "his mother indicated that

he was no longer welcome at their home and that he was an

embarrassment to the family." R. Vol. IV, Vol. 40 at 50.

In sum, we agree with the district court

that a decision to present mitigation testimony from family

members was fraught with peril, because Mr. Davis's background

contained numerous instances of conduct that was more likely

to make a jury feel unsympathetic towards him, than

sympathetic towards him. See Brewer, 51 F.3d at 1527 ("[W]hile

testimony from a family member may generally be beneficial to

a capital defendant at sentencing, we believe that, in this

case, the totality of [the family member's] revelations could

have been devastating.").

The Colorado Supreme Court correctly

concluded that "[t]he testimony of such witnesses, if

presented, would have constituted, in Truman's own words, `a

two-edged sword' at best." Davis III, 871 P.2d at 774. We

therefore conclude that he suffered no prejudice from the

failure to present such testimony.

2. Expert Testimony:

Mr. Davis also argues that he was

prejudiced by the failure to investigate and present expert

testimony on the nature and effects of Mr. Davis's severe

alcoholism, as well as on the relationship between Mr. Davis

and Ms. Fincham. At the time of the trial, Mr. Truman sought

the assistance of a psychiatrist, Dr. Seymour Z. Sundell.

After examining Mr. Davis, Dr. Sundell concluded that Mr.

Davis's history and background, including his history of

alcoholism, were not useful in mitigation.

Mr. Davis introduced in his federal habeas

proceeding reports by Dr. Gary Forrest, an expert on the

effects of alcoholism, and by Dr. Chris Hatcher, an expert on

relative accomplice liability. He claims comparable reports

should have been submitted in the penalty phase of his trial,

and that the failure to do so prejudiced him. Dr. Forrest's

report described Mr. Davis as "clearly a chronic alcoholic

with a concurrent personality disorder" and further opined

that "it is highly probable that Mr. Davis was both

intoxicated and mentally impaired when Virginia May was

murdered." Pet'r's Ex. No. 111, Appellee's Addendum.

Aside from the fact that the report itself

contains some descriptions of Mr. Davis that might not evoke

sympathy at all from a jury,

the mitigatory thrust of Dr. Forrest's report -- that Mr.

Davis was both intoxicated and mentally impaired when Ms. May

was murdered -- was undermined by the fact that there was no

actual evidence of intoxication when the Davises were first

stopped by police on the road, following the murder, as well

as by Mr. Davis's own testimony in which he specifically

recalled the murder and his involvement in it.

Moreover, the jury already knew that Mr.

Davis had a drinking problem, and that he had been drinking

the day of the murder. Thus, Dr. Forrest's conclusions in his

report would have either been unsupported by direct evidence

at the time of the murder, or would have been duplicative of

other evidence already before the jury.

Mr. Davis further argues that, besides Dr.

Forrest's expert report and testimony, Mr. Truman should have

more generally explored Mr. Davis's alcoholism as a mitigating

circumstance. Mr. Truman testified in the Rule 35(c)

proceeding that one reason he declined to explore alcoholism

as a mitigator is because the jury might have reacted

negatively to the fact that Mr. Davis had been treated

numerous times for alcoholism. See Jones v. Page, 76 F.3d 831,

846 (7th Cir. 1996) (noting that failure to introduce evidence

of petitioner's long history of substance abuse "was a

reasonable tactical choice because such evidence was a `double-edged

sword,' that is, it could easily have been considered either

aggravating or mitigating evidence"), petition for cert. filed,

(U.S. June 28, 1996) (No. 96-5064). We agree that it is just

as likely the jury would react negatively to Mr. Davis's

repeated failures to effectively address his alcoholism.

Similarly, Dr. Hatcher's report examines in

considerable detail the history of the relationship between Mr.

Davis and Ms. Fincham. He draws the conclusion that the

evidence leads to "serious questions as to who was the

dominant individual in the commission of this abduction/homicide."

Pet'r's Ex. No. 112, Appellee's Addendum.

However, any implication or persuasive

suggestion that Ms. Fincham was the dominant actor in the

crime was wholly undermined by Mr. Davis's own statement that

he was the main actor and that Ms. Fincham was much less

culpable. Even if Dr. Hatcher's report permits the inference

that Mr. Davis was simply lying when he testified against

himself, the jury was nonetheless confronted with that clear

testimony, under oath, in which Mr. Davis recounted the crime

in a manner completely contrary to the way Dr. Hatcher's

report suggests the crime occurred.

It is important to note that the jury was

able to evaluate Mr. Davis's credibility and demeanor when he

testified, as we, an appellate court, cannot. They were

further able to evaluate his credibility in context -- that is,

having observed him sitting in the courtroom throughout the

duration of his trial. We therefore cannot conclude that there

is a reasonable probability that, were those two expert

reports presented to the jury, the jury would have concluded

that death was not the appropriate sentence.

3. Other Acquaintances:

Mr. Davis also asserts he suffered

prejudice from Mr. Truman's failure to call other mitigation

witnesses, such as people who lived for awhile in the same

apartment building as the Davises, and the Davises' employer.

Such evidence was, however, either as likely to harm as help

Mr. Davis in front of the jury, or was also directed at

showing that Ms. Fincham was the dominant figure in the Davis

relationship, and by implication the dominant figure in the

murder, a proposition which Mr. Davis's own testimony

effectively rebutted.

Among the items of testimony Mr. Davis now

claims should have been presented was testimony from Clint and

Victoria Hart, who at one time lived in the same apartment as

the Davises. In an interoffice memorandum prepared for Mr.

Davis's first attorneys, public defenders, an investigator

reported a conversation he had with the Harts, in which they

said the following things about the Davises:

". . . [T]hey [the Davises] were ripping

everybody off, they would borrow money and never paid it back,

they were charging for services at the apartments giving

receipts for the services and pocketing the money then blaming

the owner for having to charge for the services.

. . . Gary drank a lot and . . . they were

swingers and tried to get people to swap partners and even

jokingly approached them about doing it. . . .

. . . .

. . . [B]oth Gary and Becky were bull

shitters but Becky seemed to have the upper hand on that and .

. . they both lied consistently about everything . . . .

. . . Becky acted like she was [in charge]

but Gary was the one that really was, he was more subdued

where as Becky was talkative and would just rattle on

especially when she was lieing [sic]."

Interoffice Mem. dated 9/10/86, Appellee's

Addendum. Such negative information about the Davises was

obviously more likely to harm rather than help Mr. Davis in

front of the jury, and certainly suggested that finding truly

helpful mitigating testimony from acquaintances was going to

be extremely difficult. We therefore see no prejudice from Mr.

Truman's decision not to present testimony from the Harts.

Mr. Davis also argues Mr. Truman should

have presented testimony from Robert Russell, an acquaintance

of Mr. Davis and Leona Coates. In a memorandum prepared for Mr.

Davis's first attorneys, Investigator Jim Smith described an

interview with Mr. Russell, in which Mr. Russell generally

described how he and Mr. Davis used to go drinking together,

and stated that Mr. Davis was not unfaithful to Leona Coates

during their marriage. Mr. Russell also said he was "surprised"

to hear of Mr. Davis's involvement in the murder. Interoffice

Mem. dated 10/9/86, R. Vol. VI.

In another memorandum prepared in

connection with Mr. Davis's habeas petition, Mr. Russell

described Mr. Davis as a good, kind and dependable father and

worker, without "a mean bone in his body." Pet'r's Ex. No.

107, R. Vol. IX. He further offered his opinion that "the

murder had to do with alcohol and someone else's influence."

Id. We again see no prejudice to Mr. Davis from the failure to

present testimony from Mr. Russell, given its generality and

vagueness in 1986 (merely expressing "surprise" about Mr.

Davis's involvement in the murder).

Even as elaborated nine years later, Mr.

Russell's characterization of Mr. Davis as lacking "a mean

bone in his body" is flatly inconsistent with a multitude of

other evidence about Mr. Davis, and the reference to alcohol

does little to help Mr. Davis other than to raise once again

all of the problems discussed above with using alcoholism as a

mitigating circumstance in Mr. Davis's particular case.

Finally, Mr. Davis argues he suffered

prejudice from the failure to present testimony from Pauline

Cowell, the woman for whom the Davises worked at the time of

the May murder. In the same memorandum prepared in 1986 by

Investigator Jim Smith, Mr. Smith described an interview with

Ms. Cowell, in which she said that Mr. Davis "was usually very

shy around her," and that she "does not believe that Gary

killed Ginny [May], she is not sure what role he played in it

but she does not believe he did it." Interoffice Mem. dated

10/9/86, R. Vol. VI. She also said that "the stories they,

especially Becky told, turned out to be half truths or out

right lies." Id.

As with the other acquaintance

testimony, it is hard to see how this would have made any

difference with the jury. Ms. Cowell said she did not believe

Mr. Davis killed Ms. May, but her otherwise unsupported belief

was completely contradicted by Mr. Davis's own testimony. Ms.

Cowell also offered that both the Davises told "half truths or

out right lies."

That is hardly likely to positively impact the jury

deliberating Mr. Davis's fate.

In sum, we find no prejudice from the

failure to call these various acquaintances of Mr. Davis to

testify in the penalty phase of the trial.

4. Prison Records:

Mr. Davis also argues that Mr. Truman

should have presented more testimony supportive of the

statutory mitigator that Mr. Davis would not be a continuing

threat to society. Mr. Truman did present testimony in the

penalty phase from Lieutenant Allen, who had supervised Mr.

Davis while he was in the Adams County jail awaiting trial,

and who testified to his good conduct during his incarceration.

Mr. Davis argues a better witness

concerning his conduct while in prison would have been Leonard

Foster, who supervised Mr. Davis while he was in prison for

his prior sexual assault conviction. Mr. Foster told an

investigator from the Federal Public Defender's office that Mr.

Davis was a model prisoner during that time. He further stated

that, had he been asked to testify at the time of Mr. Davis's

trial, he would have stated his opinion that "Gary Davis could

successfully serve a term of life imprisonment." Sholl Aff.

Para(s) 11, Pet'r's Ex. No. 109, R. Vol. IX.

Although Mr. Davis for some reason now

believes that Mr. Foster would have provided the better

testimony in mitigation, Mr. Foster's testimony basically

duplicates that of Lieutenant Allen. Thus, Mr. Davis's conduct

while incarcerated was already before the jury. The failure to

present Mr. Foster to provide essentially the same testimony

did not prejudice Mr. Davis.

Moreover, additional testimony as to Mr.

Davis's ability to function well and adjust comfortably to

prison life might have negatively affected jurors who wished

to see that Mr. Davis received a severe penalty for an

admittedly horrible crime. Details from Mr. Davis's prison

records would also, of course, have reminded the jury of Mr.

Davis's criminal history, with its increasingly violent

behavior.

Furthermore, against all of this evidence

which Mr. Davis presented in the federal district court, and

which he claims Mr. Truman erroneously failed to present in

the penalty phase of his trial, we must weigh the aggravating

factors present in this case. Although Mr. Davis challenges

five of the six aggravating factors found by the jury, as we

explain below, we find four of the five were constitutional

and supported by the evidence, and the submission of the

unconstitutionally vague aggravator was harmless error.

As we have stated before, the sentence in

this case was not "`only weakly supported by the record.'"

Brewer, 51 F.3d at 1527 (quoting Strickland, 466 U.S. at 694).

Indeed, Mr. Davis's own words, detailing his participation in

the crime and his assumption of full responsibility for it,

were fresh in the jurors' minds. See Thompson v. Calderon, 86

F.3d 1509, 1525 (9th Cir. 1996) ("The State's case against [petitioner]

was strong . . . . [Petitioner] himself made it much stronger

by testifying after counsel advised him not to testify."). As

we stated in Brewer:

Given the State's overwhelming case against

him, the number and gravity of the aggravating circumstances

found by the jury, and the nature of the crime itself, we do

not believe that the speculative, conclusory, and possibly

damaging mitigating evidence offered now . . . would have

resulted in the imposition of a sentence other than death.

Brewer, 51 F.3d at 1527. We are equally

confident that the speculative, cumulative and almost

certainly damaging evidence offered now in this case would not

have resulted in the imposition of a different sentence. See

Marek v. Singletary, 62 F.3d 1295, 1300-01 (11th Cir. 1995) ("Given

the particular circumstances of this case and the overwhelming

evidence against Marek, evidence of an abusive and difficult

childhood would have been entitled to little, if any,

mitigating weight."), cert. denied, _____ U.S. _____, 117 S.Ct.

113, 136 L.Ed.2d 65 (1996) Bonin v. Calderson, 59 F.3d 815,

836 (9th Cir. 1995) ("`[I]n cases with overwhelming evidence

of guilt, it is especially difficult to show prejudice from a

claimed error on the part of trial counsel.'") (quoting United

States v. Coleman, 707 F.2d 374, 378 (9th Cir.), cert. denied,

464 U.S. 854 (1983)), cert. denied, _____ U.S.

_____, 116 S. Ct. 718, 133 L.Ed.2d 671 (1996); Andrews v.

Collins, 21 F.3d 612, 624 (5th Cir. 1994) (holding that in

light of evidence that defendant stood over victim and shot

him directly in forehead with a bullet altered to cause more

devastation on impact, defendant suffered no prejudice from

counsel's alleged ineffectiveness), cert. denied, 115 S. Ct.

908 (1995); People v. Rodriguez, 914 P.2d 230, 296 (Colo.

1996) ("Given the brutal circumstances surrounding the murder

of [the victim] and the overwhelming evidence of aggravation

against [defendant], . . . trial counsel's failure to present

the proposed mitigating evidence of child abuse [did not]

materially affect[] the imposition of" the death penalty.).

II. Statutory Aggravators.

The trial court instructed the jury on six

statutory aggravators.

The jury found the existence of all six beyond a reasonable

doubt. Mr. Davis challenges five of the six.

Colorado's capital sentencing scheme

involves four steps. The Colorado Supreme Court has described

it as follows:

First, the jury must determine if at least

one of the statutory aggravating factors exists. Section(s)

16-11-103(2)(a)(I), -(6). If the jury does not unanimously

agree that the prosecution has proven the existence of at

least one statutory aggravator beyond a reasonable doubt, the

defendant must be sentenced to life imprisonment.

16-11-103(1)(d),-(2)(b)(I), -(2)(c). Second, if the jury has

found that at least one statutory aggravating factor has been

proven, the jury must then consider whether any mitigating

factors exist. 16-11-103(2)(a)(II), -(5). "There shall be no

burden of proof as to proving or disproving mitigating factors,"

Section(s) 16- 11-103(1)(d), and the jury need not unanimously

agree upon the existence of mitigating factors. Third, the

jury must determine whether "sufficient mitigating factors

exist which outweigh any aggravating factor or factors found

to exist." Section(s) 16-11-103(2)(a)(II). Fourth, and finally,

if the jury finds that any mitigating factors do not outweigh

the proven statutory aggravating factors, it must decide

whether the defendant should be sentenced to death or to life

imprisonment. Section(s) 16-11-103(2)(a)(III).

People v. Tenneson, 788 P.2d 786, 789 (Colo.

1990) (citations omitted); see also People v. White, 870 P.2d

424, 438 (Colo.), cert. denied, _____ U.S. _____, 115 S. Ct.

127, 130 L.Ed.2d 71 (1994).

"The constitutional validity of aggravating

factors is a question of law subject to de novo review."

United States v. McCullah, 76 F.3d 1087, 1107 (10th Cir.

1996). What happens when an unconstitutional aggravator has

been submitted to the sentencer depends, in part, on whether

the state sentencing scheme involves weighing of aggravating

and mitigating circumstances.

In a weighing state, "after a jury has

found a defendant guilty of capital murder and found the

existence of at least one statutory aggravating factor, it

must weigh the aggravating factor or factors against the

mitigating evidence." Stringer v. Black, 503 U.S. 222, 229

(1992). By contrast, in a non-weighing state "the jury must

find the existence of one aggravating factor before imposing

the death penalty, but aggravating factors as such have no

specific function in the jury's decision whether a defendant

who has been found to be eligible for the death penalty should

receive it under all the circumstances of the case." Id. at

229-30, 112 S.Ct. at 1136.

If an unconstitutional aggravating factor

has been submitted to the jury in a weighing state, an

appellate court may independently reweigh the aggravating and

mitigating factors, omitting the unconstitutional one, and

determine if the sentence is nonetheless appropriate. Clemons

v. Mississippi, 494 U.S. 738, 750, 110 S.Ct. 1441, 1449, 108

L.Ed.2d 725 (1990). Alternatively, the appellate court may

conduct a harmless error analysis, determining whether the

submission to the jury of the unconstitutional aggravator was

harmless. Id. at 752, 110 S.Ct. at 1450.

Additionally, the Supreme Court has

indicated that "a state appellate court may itself determine

whether the evidence supports the existence of the aggravating

circumstance as properly defined," Walton v. Arizona, 497 U.S.

639, 654, 110 S.Ct. 3047, 3057, 111 L.Ed.2d 511 (1990), and on

federal habeas review of such a decision, "the state court's

application of the narrowing construction should be reviewed

under the `rational factfinder' standard of Jackson v.

Virginia, 443 U.S. 307 [99 S.Ct. 2781, 61 L.Ed.2d 560]

(1979)." Richmond v. Lewis, 506 U.S. 40, 47, 113 S.Ct. 528,

121 L.Ed.2d 411 (1992).

In a non-weighing state, by contrast, so

long as the sentencing body finds at least one valid

aggravating factor, the fact that it also finds an invalid

aggravating factor does not infect the formal process of

deciding whether death is an appropriate penalty. Assuming a

determination by the state appellate court that the invalid

factor would not have made a difference to the jury's

determination, there is no constitutional violation resulting

from the introduction of the invalid factor in an earlier

stage of the proceeding.

Stringer, 503 U.S. at 232; see also Tuggle

v. Netherland, _____ U.S. _____, 116 S. Ct. 283, 133 L.Ed.2d

251 (1995); Zant v. Stephens, 462 U.S. 862, 103 S.Ct. 2733, 77

L.Ed.2d 235 (1983); Tuggle v. Netherland, 79 F.3d 1386 (4th

Cir. 1996) (applying harmless error analysis to Ake v.

Oklahoma, 470 U.S. 68, 105 S.Ct. 1087, 84 L.Ed.2d 53 (1985),

error in capital sentencing proceeding in a non-weighing state),

cert. denied, _____ U.S. _____, 117 S.Ct. 237, 136 L.Ed.2d 166

(1996).

Step three of Colorado's four-step capital

sentencing scheme clearly requires weighing of aggravating and

mitigating circumstances. Step four, however, "require[s] the

jury to make an independent decision whether to impose a

sentence of life imprisonment or death where mitigating

factors did not outweigh aggravating factors." People v.

District Court, 834 P.2d 181, 185 (Colo. 1992); see also

People v. Young, 814 P.2d 834, 841 (Colo. 1991). It thus is

more similar to the sentencing decision made in a non-weighing

state.

The Supreme Court has not specifically indicated whether the

Clemons reweighing/harmless-error analysis or the Zant

analysis applies to states having "hybrid" systems like

Colorado's. See Flamer v. Delaware, 68 F.3d 736, 769 (3d Cir.

1995) (Lewis, J., dissenting), cert. denied, _____ U.S. _____,

116 S. Ct. 807, 133 L.Ed.2d 754 (1996).

Mr. Davis suggests that a harmless error

analysis is not possible under Colorado's capital sentencing

scheme, apparently because of the fourth step. While he is not

completely clear, we assume his argument is that a harmless-error

analysis is unavailable in a non-weighing scheme, and

therefore unavailable in Colorado because of that fourth step.

We disagree with his characterization of

Colorado's capital sentencing scheme. While the fourth step in

the sentencing process does indeed appear to give the jury the

opportunity to consider any and all reasons for imposing a

sentence of life or death, the third step clearly and

specifically requires the jury to weigh aggravating and

mitigating factors. The jury does not reach the fourth step

unless it has determined that any mitigating factors do not

outweigh the proven statutory aggravators. Because weighing

thus performs a critical function in the jury's sentencing

scheme, we apply, where appropriate, the Clemons harmless

error analysis.18 We turn now to the specific allegations of

error

A. Aggravating Factor of "Avoiding or

Preventing Lawful Arrest or Prosecution":

One of the statutory aggravators presented

to the jury was the following:

The class I felony was committed for the

purpose of avoiding or preventing a lawful arrest or

prosecution or effecting an escape from custody. This factor

shall include the intentional killing of a witness to a

criminal offense.

Colo. Rev. Stat. Section(s)

16-11-103(6)(k). Mr. Davis objected to the instruction on the

ground that the aggravator should only apply when a witness of

a crime is killed to prevent the investigation or prosecution

of that other, separate, crime or when a law enforcement

officer is killed while attempting to arrest someone. The

trial court overruled the objection.

To be constitutional, an aggravating

circumstance must "not apply to every defendant convicted of a

murder; it must apply only to a subclass of defendants

convicted of murder." Tuilaepa v. California, 512 U.S. 967,

_____, 114 S. Ct. 2630, 2635, 129 L.Ed.2d 750 (1994). "If the

sentencer fairly could conclude that an aggravating

circumstance applies to every defendant eligible for the death

penalty, the circumstance is constitutionally infirm." Arave

v. Creech, 507 U.S. 463, 474 (1993). Additionally, "the

aggravating circumstance may not be unconstitutionally vague."

Tuilaepa, 512 U.S. at _____, 114 S. Ct. at 2635.

The Colorado Supreme Court agreed with the

state's interpretation of this aggravator, that it "is

appropriate if the evidence indicates that a defendant has

murdered the victim of a contemporaneously or recently

perpetrated offense and the reason for the murder was to

prevent the victim from becoming a witness." Davis I, 794 P.2d

at 187. The "antecedent crime must be one which is not

inherent or necessarily incident to murder such as assault or

battery, otherwise every murder would be punished by death."

Id. at 187 n.22. The Colorado court observed that "[b]y

putting the focus on the purpose of the murder, this

aggravating factor cannot be said to include all murder

victims because they are all potential witnesses." Id. at 187.

Mr. Davis argues this interpretation fails

to effectively narrow the class of defendants subject to the

death penalty, because all murder victims are thereby

prevented from testifying against their murderers. He argues "Mrs.

May was not a witness to a criminal offense independent of the

murder. Rather, the crimes upon her that she had witnessed

were part of the same continuous criminal transaction as the

murder." Appellant's Opening Br. at 78.

We agree with the Colorado Supreme Court,

whose analysis the district court adopted, that the statutory

aggravator sufficiently narrows the class of defendants to

whom it applies. Several other states have a similar statutory

aggravating circumstance. Arkansas, for example, includes

among its aggravating circumstances that "[t]he capital murder

was committed for the purpose of avoiding or preventing an

arrest or effecting an escape from custody." Ark. Code Ann.

Section(s) 5-4-604(5). The Eighth Circuit recently rejected an

argument that the provision "does not genuinely narrow the

class of persons eligible for the death penalty." Wainwright

v. Lockhart, 80 F.3d 1226, 1231 (8th Cir. 1996), cert. denied,

_____ U.S. _____, 117 S.Ct. 395, 136 L.Ed.2d 310 (1996).

In Wainwright, the court held that the

aggravator was properly applied to a murder which was

committed in the course of a robbery, in order to prevent the

murderer's identification by the victim. See also Joubert v.

Hopkins, 75 F.3d 1232, 1247 (8th Cir.) (upholding validity of

Nebraska statutory aggravator that the killing was committed

to hide the perpetrator's identity where defendant kidnaped

victims before killing them), cert. denied, _____U.S.

_____,116 S. Ct. 2574, 135 L.Ed.2d 1090 (1996); Ruiz v. Norris,

71 F.3d 1404, 1408 (8th Cir. 1995), cert. denied, _____ U.S.

_____, 177 S.Ct. 384, 136 L.Ed.2d 301 (1996); Miller v. State,

605 S.W.2d 430, 439-40 (Ark. 1980) (upholding validity of

statutory aggravator that murder was committed for purpose of

avoiding arrest where defendant robbed victim before killing

him), cert. denied,

450 U.S. 1035 (1981); Thompson v. State, 648

So.2d 692, 695 (Fla. 1994) (upholding validity of statutory

aggravator that murder was committed for purpose of avoiding

arrest where defendant kidnaped and robbed victims before

murdering them), cert. denied, _____ U.S. _____, 115 S. Ct.

2283, 132 L.Ed2d 286 (1995); Walker v. State, 671 So.2d 581,

602 (Miss. 1995) (upholding validity of statutory aggravator

that murder was committed for purpose of avoiding or

preventing a lawful arrest where defendants kidnaped and raped

victim before murdering her), petition for cert. filed, (U.S.

July 16, 1996) (No. 96-5259); State v. Hightower, 680 A.2d

649, 663 (N.J. 1996) (upholding validity of statutory

aggravator that murder was committed to avoid apprehension

where victim was robbed prior to murder, and observing that "[t]he

fact that a murder occurs contemporaneously with the witnessed

underlying crime does not mitigate the evil of killing a

potential witness"); State v. Gregory, 459 S.E.2d 638, 664 (N.C.

1995) (upholding validity of statutory aggravator that murders

were committed for the purpose of avoiding or preventing a

lawful arrest where defendants had kidnaped and raped victims

prior to killing them), cert. denied, _____U.S. _____,116 S.

Ct. 1327, 134 L.Ed.2d 478 (1996). In each of these cases, the

aggravating circumstance was applied where an antecedent crime

(rape or kidnaping or robbery) occurred, and the murderer

killed the victim to prevent the victim's identification of

the murderer for the antecedent crime.

That is exactly what occurred in this case:

Mr. Davis testified that he killed Ms. May so she would not be

a live witness. R. Vol. V, Vol. 32 at 73. Further, the

evidence in this case concerning the Davises' motivation for

murdering Ms. May, which Mr. Davis does not dispute, supports

the conclusion that their motivation for kidnaping Ms. May was

to subject her to various sexual abuses, and she was then

murdered so she would not identify them. We find nothing

unconstitutional in the application of this aggravator to Mr.

Davis.

B. Application of the "Party to an

Agreement" Aggravator:

Mr. Davis also challenges the statutory

aggravator that Mr Davis "has been a party to an agreement to

kill another person in furtherance of which a person has been

intentionally killed." Colo. Rev. Stat. Section(s)

16-11-103(6)(e). He argues, as he did at his trial, that this

aggravator should only apply to contract killings, not to

"simple conspiracy." Appellant's Opening Br. at 87.

As the Supreme Court has stated, "[s]tates

must properly establish a threshold below which the [death]

penalty cannot be imposed." Romano v. Oklahoma, 114 S. Ct.

2004, 2009 (1994); McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279, 305

(1987). To that end, they must "establish rational criteria

that narrow the decisionmaker's judgment as to whether the

circumstances of a particular defendant's case meet the

threshold." Id. We have recognized that "aggravating

circumstances must be described in terms that are commonly

understood, interpreted and applied.

To truly provide guidance to a sentencer

who must distinguish between murders, an aggravating

circumstance must direct the sentencer's attention to a

particular aspect of a killing that justifies the death

penalty." Cartwright v. Maynard, 822 F.2d 1477, 1485 (10th

Cir. 1987), aff'd, 486 U.S. 356 (1988). An aggravating

circumstance cannot be so vague that it fails to effectively

channel the sentencer's discretion, and it must contribute to

the kind of individualized sentencing necessary for the

imposition of the death penalty. "Beyond these limitations, .

. . the Court has deferred to the State's choice of

substantive factors relevant to the penalty determination."

California v. Ramos, 463 U.S. 992, 1001 (1983).

Mr. Davis makes no specific argument why

the "party to an agreement" aggravator is not a rational

criterion by which Colorado could select those for whom the

death penalty is permissible. He simply argues that the

Colorado legislature did not intend it to apply other than to

contracts for hire, an argument the Colorado Supreme Court

rejected, and that no other state includes such an aggravator

in its capital sentencing scheme. Neither argument persuades

us that habeas relief is necessary.

The Colorado Supreme Court examined the

legislative history behind the statute, and determined that it

was not limited to "contract-murders," as Mr. Davis argues.

Absent some compelling argument that that interpretation

violates the federal constitution, we will not disturb it. See

Bowser v. Boggs, 20 F.3d 1060, 1065 (10th Cir.) ("We will not

second guess a state court's application or interpretation of

state law on a petition for habeas unless such application or

interpretation violates federal law."), cert. denied, _____U.S.

_____,115 S. Ct. 313, 130 L.Ed.2d 275 (1994); Hamm v. Latessa,

72 F.3d 947, 954 (1st Cir. 1995) (same), cert. denied, _____U.S.

_____, 117 S.Ct. 154, 136 L.Ed.2d 275; see also Mansfield v.

Champion, 992 F.2d 1098, 1100 (10th Cir. 1993) ("In a habeas

corpus proceeding under section 2254, a federal court should

defer to a state court's interpretation of state law in

determining whether an incident constitutes one or more than

one offense for double jeopardy purposes."). And the fact that

Colorado may be the only state which permits such an

aggravator by itself indicates no constitutional infirmity.

As the Supreme Court has made clear, unless

the aggravator is unconstitutionally vague on its face, or

otherwise impedes the requirement that sentencing

determinations be individualized, states are free to select

whatever substantive criteria they wish to determine who is

eligible for the death penalty. See Spaziano v. Florida, 468

U.S. 447, 464 (1984) ("The Eighth Amendment is not violated

every time a State reaches a conclusion different from a

majority of its sisters over how best to administer its

criminal laws.").

C. Consideration of the "Especially

Heinous, Cruel or Depraved" Aggravator:

The jury was also instructed on the

aggravating factor that "[t]he defendant committed the offense

in an especially heinous, cruel, or depraved manner." Colo.

Rev. Stat. Section(s) 16-11-103(6)(j). The trial court offered

no elaboration of the language of the statute, and overruled

Mr. Davis's objection to the aggravator as unconstitutionally

vague.

The United States Supreme Court in Maynard

v. Cartwright, 486 U.S. 356 (1988), held that Oklahoma's "especially

heinous, atrocious or cruel" statutory aggravator, if

presented to a jury without further elaboration and

explication, was unconstitutionally vague. The Colorado

Supreme Court in Davis I correctly concluded that, under

Cartwright, the trial court improperly permitted the jury to

consider the "especially heinous, cruel or depraved"

aggravator.

The Colorado court further held that, under

Proffit v. Florida,

428 U.S. 242 (1976), "the prosecutor could prove

the existence of this aggravator by showing that the defendant

committed the crime in a `conscienceless or pitiless' manner

which was `unnecessarily torturous to the victim.'" Davis I,

794 P.2d at 176-77. The court went on to determine whether, "beyond

a reasonable doubt, . . . had the aggravator properly been

narrowed the jury would have returned a verdict of death." Id.

at 179. It concluded that it would have, and that the error

was therefore harmless beyond a reasonable doubt.

Mr. Davis argues the Colorado Supreme Court

erred in two respects: (1) it emphasized heavily the evidence

supporting the "heinous, cruel or depraved" aggravator, while

failing to mention or discuss any mitigating evidence in

conducting its harmless error review; and (2) harmless error

review is impossible because of Colorado's peculiar capital

sentencing scheme. We have already rejected this second

argument and concluded that harmless error analysis is

available. We must still determine whether the Colorado

Supreme Court properly cured the error, either by correctly

applying a narrowing construction or otherwise conducting a

harmless error analysis.

The Colorado Supreme Court held that the

properly narrowed definition of the "heinous, cruel or

depraved" aggravator was the one set out in Proffit. Mr. Davis

does not dispute the validity of that narrowed definition. He

simply disagrees with the way the Colorado court applied that

standard, arguing it is "`nothing but a facile guess at what

the jury would have found under a totally hypothetical set of

instructions that realistically could not possibly have been

within the contemplation of any juror when this case was

decided.'" Appellant's Opening Br. at 81 (quoting Davis I, 794

P.2d at 222 (Quinn, C.J., dissenting)). He further argues the

court made no reference to the mitigating evidence presented

to the jury.

When reviewing a state court's application

of a properly narrowed definition of a facially vague

aggravator, we "uphold the state court's finding so long as a

rational factfinder could have found the elements identified

by the construction -- here, that the crime involved [conscienceless

or pitiless conduct and was unnecessarily torturous to the

victim]." Hatch v. Oklahoma, 58 F.3d 1447, 1469 (10th Cir.

1995), cert. denied, _____U.S. _____,116 S. Ct. 1881, 135 L.Ed.2d

176 (1996); see also Richmond v. Lewis, 506 U.S. 40, 47

(1992); Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307, 319 (1979).

The Colorado Supreme Court found the

necessary facts to establish that the murder was committed in

a conscienceless or pitiless manner, and was unnecessarily

torturous to the victim. Davis I, 794 P.2d at 179-80. It then

held that, because a jury given a properly narrowed definition

of the "heinousness" aggravator would still have found the

aggravator established, it was harmless error beyond a

reasonable doubt to instruct the jury without that narrowed

definition. Under Richmond, Walton and our Hatch decision, we

perceive no error in the Colorado Supreme Court's "curing" the

submission to the jury of the vague aggravator.

Alternatively, were we to agree that,

despite its use of the term "harmless error," the Colorado

Supreme Court did not properly conduct a harmless error

analysis because it did not explicitly consider mitigating

evidence, we could apply the harmless error standard of Brecht

v. Abrahamson, 507 U.S. 619, 637 (1993). Under Brecht, federal

courts on habeas review of trial errors must ask "whether the

error `had substantial and injurious effect or influence in

determining the jury's verdict.'" Id. (quoting Kotteakos v.

United States, 328 U.S. 750, 776 (1946)). In making that

evaluation, the Supreme Court has indicated that "where the

record is so evenly balanced that a conscientious judge is in

grave doubt as to the harmlessness of an error," the error is

not harmless. O'Neal v. McAninch, ___ U.S. ___, ___, 115 S. Ct.

992, 995, 130 L.Ed.2d 947 (1995).

Thus, under Brecht, we would inquire

whether the submission of the vague aggravator had a

substantial and injurious effect on the jury's verdict. As we

have previously stated, "our task is not merely to determine

whether there was sufficient evidence to convict . . . in the

absence of [the error]." Tuttle v. Utah, 57 F.3d 879, 884

(10th Cir. 1995). Rather, it is to "determine, in light of the

entire record, whether [the error] so influenced the jury that

we cannot conclude that it did not substantially affect the

verdict, or whether we have grave doubt as to the harmlessness

of the error alleged." Id.

Applying that standard, we conclude that

the submission to the jury of the vague "heinousness"

aggravator was harmless error. The jury was given six

statutory aggravators. Mr. Davis does not dispute the

applicability of one of the six (that the crime was committed

while he was on parole for another crime). We have just held

that two other aggravators, that the murder was committed to

avoid arrest and that Mr. Davis was a party to an agreement to

murder, were properly submitted to the jury and supported by

the evidence. Thus, three valid aggravators were clearly

before the jury.

In discussing the "heinous, cruel or

depraved" aggravator in his closing argument, the prosecutor

did not allude to any evidence or facts not already properly

before the jury. Nor was that particular aggravator emphasized

disproportionately in that closing argument. The valid

aggravators, in our view, powerfully outweighed the mitigating

evidence before the jury. In light of the entire record, we

conclude that the submission of the unconstitutionally vague "heinousness"

aggravator to the jury did not have a "substantial and

injurious effect or influence in determining the jury's

verdict." Brecht, 507 U.S. at 637, 113 S.Ct. at 1722.

D. Consideration of "Felony Murder" and

"Kidnaping" Aggravators:

Two additional aggravating factors

submitted to the jury were that Davis committed the felony of

second degree kidnaping, and "in the course of or in

furtherance of such or immediate flight therefrom, he

intentionally caused the death of a person other than one of

the participants," Colo. Rev. Stat. Section(s)

16-11-103(6)(g), and that he "intentionally killed a person

kidnapped or being held as a hostage by him or by anyone

associated with him." Colo. Rev. Stat. Section(s)

16-11-103(6)(d). Mr. Davis argues that these two aggravating

circumstances "involve the same indivisible course of conduct,"

Appellant's Opening Br. at 84, and that the submission of both

to the jury fails to genuinely narrow the class of defendants

eligible for the death penalty.

The Colorado Supreme Court in Davis I found

that Mr. Davis "did not object to the presentation to the jury

of the `felony murder' aggravator[,] [n]or did he present a `doubling

up' argument to the court during the presentation of the `kidnaping'

aggravator." Davis I, 794 P.2d at 188. The court went on to

observe that it was aware of no federal cases addressing the

constitutionality, under federal law, of overlapping or

duplicative aggravators, but found no error in Mr. Davis's

case "[b]ecause, by the plain language of our statute, both

aggravators applied under the facts of this case." Id. at 189.

The court also observed that the jury was instructed that it

was the weight assigned each aggravating factor, not their

mere number, that guided the jury's deliberation. Id. Thus,

the Colorado court found no error.

Since Davis I, our court has held that the

submission of duplicative aggravating factors is

constitutional error, at least under the weighing scheme of

the federal death penalty statute, 21 U.S.C. Section(s) 848.

United States v. McCullah, 76 F.3d 1087, 1111-12 (10th Cir.

1996); see also United States v. Tipton, 90 F.3d 861, 899 (4th

Cir. 1996). In McCullah, we remanded for a "reweighing of the

aggravating and mitigating factors." McCullah, 76 F.3d at

1112.

The state responds that Colorado's

particular capital sentencing scheme includes both a weighing

and a non-weighing component, and the fourth and last step in

the sentencing process makes it ultimately a non-weighing

state in which, under Zant v. Stephens, 462 U.S. 862 (1983),

duplicative aggravators are not a problem. As we have

indicated, in our view, Colorado's capital sentencing scheme

contains a crucial weighing component. We thus treat it as a

weighing state. In federal habeas review of a state court

trial in which an error occurred in the submission of

aggravating factors to a jury which must weigh aggravating and

mitigating factors, we may conduct a harmless error analysis.

See Clemons, 494 U.S. at 750; see also Brecht, 507 U.S. at

637.

Applying the Brecht standard, we must

determine whether, in light of the entire record, the

submission of the two aggravators addressing the same basic

conduct had a "substantial and injurious effect or influence"

on the jury's verdict. Id. As we stated above in discussing

the effect of the "heinousness" factor on the jury, the jury

had three valid aggravating factors before it. It also had Mr.

Davis's own statement describing his involvement in the crime,

and taking full responsibility for it. The jury was further

specifically instructed that it could "assign any weight you

wish to each aggravating and mitigating factor. It is the

weight assigned to each factor, and not the number of factors

found to exist that is to be considered." Jury Instruction No.

2, R. Vol. IV, Vol. 2 at 389.

Similarly, Instruction No. 5 directed the

jury that the weighing of mitigating and aggravating factors "is

not a mere counting process in which numbers of aggravating

factors are weighed against numbers of mitigating factors. The

number of the factors found is not determinative. . . . You

must consider the relative substantiality and persuasiveness

of the existing aggravating and mitigating factors in making

this determination." Jury Instruction No. 5, id. at 394.

We assume that the jury did not blindly or

unthinkingly add up the total number of aggravators, and weigh

that number against the number of mitigators. Rather, we

assume they followed the instructions to critically evaluate

each factor, applying their "common sense understanding" to

their obligation to weigh aggravating and mitigating factors.

See Boyde v. California, 494 U.S. 370, 381 (1990).

An instruction that the weighing process is

not simply a mathematical exercise, but instead requires

critical evaluation of the factors, can help to countervail

any improper influence occasioned by the submission of

duplicative aggravators. See United States v. Chandler, 996

F.2d 1073, 1093 (11th Cir. 1993) (noting that an instruction

that "the weighing process was not a mechanical one and that

different factors could be given different weight" can

alleviate concern that the jury would be influenced by the

number of aggravating factors), cert. denied, 114 S. Ct. 2724

(1994); United States v. Bradley, 880 F. Supp. 271, 289 n.8 (M.D.

Pa. 1994) (noting that a curative instruction might

countervail "any unfairness inherent in the weighing of a

duplicative factor."); see also Parsons v. Barnes, 871 P.2d