Supreme Court of Missouri

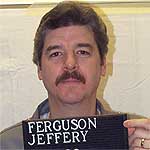

Case Style: State of Missouri, Respondent, v.

Jeffrey Ferguson, Appellant.

Case Number: SC78609

Handdown Date: 05/30/2000

Appeal From: Circuit Court of St. Louis County,

Hon. William M. Corrigan, Judge at trial; Hon. John F. Kintz, Judge at

post-conviction proceeding.

Counsel for Appellant: Janet M. Thompson

Counsel for Respondent: Catherine Chatman

Opinion Summary:

Jeffrey Ferguson was convicted of first degree

murder and sentenced to death for killing a seventeen-year-old girl

kidnapped from a St. Charles service station in 1989. His first

conviction was overturned because of instructional error. He was again

convicted of first-degree murder; the jury again recommended and the

court imposed the death penalty. He appeals this conviction and denial

of post-conviction relief.

AFFIRMED.

Opinion Author: Stephen N. Limbaugh, Jr., Judge

Opinion Vote: AFFIRMED. All concur.

Opinion

This is an appeal of defendant Jeffrey Ferguson's

second conviction and death sentence for the 1989 murder of Kelli

Hall. The first conviction was overturned because of instructional

error. State v. Ferguson, 887 S.W.2d 585 (Mo. banc 1994). In this

case, like the other, Ferguson was convicted by a jury in the St.

Louis County Circuit Court of murder in the first degree, section

565.020, RSMo 1986, and the trial court, following the jury's

recommendation, sentenced Ferguson to death. The post-conviction court

overruled his Rule 29.15 motion without an evidentiary hearing.

Because the death penalty was imposed, this Court has exclusive

jurisdiction of the appeals. Mo. Const. art. V, sec. 3; Order of June

16, 1988. The judgments are affirmed.

I. FACTS

The facts, which this Court reviews in the light

most favorable to the verdict, State v. Wolfe, 13 S.W.3d 248, 252 (Mo.

banc 2000), are as follows:

On February 9, 1989, at about 9:00 p.m., Melvin

Hedrick met Ferguson and a friend, Kenneth Ousley, at Ferguson's home.

Ferguson asked Hedrick if he would be interested in buying a .32

caliber pistol. Although Hedrick said that he was not interested, he

suggested that they take the pistol with them because they might be

able to sell it at a bar. Ferguson and Hedrick then made their way to

Brother's Bar in St. Charles, where they stayed for about forty-five

minutes to an hour. At the bar, Hedrick began to feel ill, and

Ferguson arranged for Ousley to meet them at a Shell service station

on 5th Street, near Interstate 70. Between 10:50 and 10:55 p.m.,

Ferguson and Hedrick made the short trip to the Shell station, where

Ousley was waiting in Ferguson's brown and white Blazer. Ferguson put

the .32 caliber pistol in his waistband and then walked toward the

passenger side of the Blazer as Hedrick left for home.

Seventeen-year-old Kelli Hall, the victim in the

case, worked at a Mobil service station across the street from the

Shell station where Ousley and Ferguson met. Hall's shift was

scheduled to end at 11:00 p.m., and at about that time, one of Hall's

co-workers, Tammy Adams, arrived at the Mobil station to relieve her.

A few minutes later, Robert Stulce, who knew Hall, drove up to the

Mobil station to meet a friend and noticed Hall checking and recording

the fuel levels in the four tanks at the front of the station. Stulce

also saw a brown and white Blazer, which he later identified as

identical to Ferguson's Blazer, pull in front of him and stop in the

parking lot near Hall. When Stulce looked again, Hall was facing a

white male who was standing between the open passenger door and the

body of the Blazer. The man stood very close to Hall and appeared to

have one hand in his pocket and the other hand free. Stulce then saw

Hall get into the back passenger seat of the vehicle.

In the meantime, Hall's boyfriend, Tim Parres,

waited for her in his car, which he had parked behind the station.

After waiting for Hall for about half an hour, Parres went inside the

station looking for her, but to no avail. He and Tammy Adams then

determined that Hall was not at home, but that her purse was still at

the station, and at that point they called the police.

Early the next morning, February 10, a street

maintenance worker for the City of Chesterfield found a red coat, a

blue sweater with a Mobil insignia, a white shirt, an undershirt, a

bra, underwear, and tennis shoes two to three feet off Creve Coeur

Mill Road. In the pocket of the coat was a red scarf and a Mobil

credit card slip form with notations on the back about the fuel levels

of two of the underground tanks.

On that same day, Melvin Hedrick heard on two news

reports that a girl had been abducted from a St. Charles gas station

and that police were looking for a Blazer like Ferguson's. Hedrick

called Ferguson and jokingly asked him if he abducted the girl,

whereupon Ferguson became angry and responded: "I wasn't even in St.

Charles last night. Don't tell anybody I was in St. Charles last

night." Later in the evening Ferguson called Hedrick and told him that

he thought they were just "joking around" earlier.

That night, Kenneth Ousley showed his friend Mike

Thompson two rings and asked him if he knew where they could exchange

the rings for money or cocaine. When Thompson asked where the rings

came from, Ousley replied that he and Ferguson "did a job in St.

Charles" and that Ferguson had a third ring. The next day, February

11, 1989, Ousley and Thompson sought advice from Alicia Medlock about

exchanging the rings for drugs or finding a pawnshop, but she provided

no help. On February 12, Ousley told Thompson that Ferguson knew a

woman in Jefferson County who dealt in jewelry, and that Ferguson

would handle getting rid of the rings. Sometime that day, Ferguson

offered to sell the three rings to Brenda Rosener -- the Jefferson

County woman. When Rosener asked Ferguson if they were "hot," he said

that they were "very hot." Rosener refused to buy the rings, but

Ferguson left them with her anyway and told her to think it over.

During that time, Hedrick began to think that

Ferguson was involved in the crime. On Monday morning, February 13,

1989, Hedrick contacted Glenn Young, a co-worker who was a former FBI

agent, and suggested that the FBI investigate Ferguson. Later that

day, Ferguson called Hedrick and said that he intended to leave town

because things were getting "too hot." Ferguson, accompanied by Ousley,

then drove to a friend's auto body shop where he asked to have his

Blazer painted black, explaining that people with Blazers were being

pulled over by police because of the Hall disappearance and that he

wanted to avoid being "hassled." The shop owner, however, was too busy

to do the job that day, and Ferguson and Ousley left without making an

appointment for some other day.

At about this time, the street maintenance worker

realized the significance of the clothes he found on Creve Coeur Mill

Road and turned them over to the police. The next day, Tuesday,

February 14, Kelli Hall's mother identified the clothing he found as

the clothing her daughter wore on the night she disappeared.

Several days later, on February 18, Ferguson called

Hedrick and told him that the FBI had searched his house, but had not

found anything. He urged Hedrick not to tell anyone that he was in St.

Charles at the time of the abduction and suggested that if Hedrick had

to say anything at all, he should say they were there at 10:00 p.m.,

rather than 11:00 p.m.

On February 20, Ferguson went to Brenda Rosener's

house to inquire about the rings. Because Rosener was not home,

Ferguson asked her housemate, Ed Metcalf, if he knew whether she

wanted to buy the rings. Ferguson then said that he was being

investigated in connection with Kelli Hall's disappearance, whereupon

Metcalf asked him to leave. That night, Metcalf asked Rosener to show

him the rings that Ferguson was talking about. Suspecting that the

rings were Kelli Hall's, they decided to call Michael Eifert, a

relative who was an officer with the St. Ann Police Department. After

obtaining the three rings from Metcalf and Rosener, Officer Eifert

took them to the St. Charles Police Department, and Hall's mother

identified them as her daughter's.

Early on the morning of February 22, Warren Stemme

was working on his farm in the Missouri River bottoms. As he walked by

a machinery shed, he discovered Kelli Hall's body, frozen, clothed

only in socks, and partially obscured by steel building partitions

that had been leaned up against the shed. The partitions could not

have been moved by one man alone. According to the trial testimony of

the state's forensic pathologist, Kelli Hall died from strangulation

with a broad ligature, such as a strip of cloth. The pathologist also

testified that it would have taken one to two minutes for Hall to lose

consciousness; then two or three more minutes for Hall to die; that

multiple red horizontal abrasions on Hall's neck indicated a struggle;

and, therefore, that the strangulation process could have taken longer

than several minutes.

The day that Hall's body was found, FBI agents and

St. Charles police arranged for Melvin Hedrick to wear a body

transmitter and meet with Ferguson at a bar. Hedrick asked Ferguson

what happened to the gun he had with him the night of the abduction,

and Ferguson responded, "Just forget the gun. It's gone. I got rid of

it." Hedrick said, "You got rid of it?" Ferguson replied, "Hell,

yeah." Hedrick told Ferguson that he suspected his involvement in the

abduction, and Ferguson stated he could understand why Hedrick was

suspicious. When Hedrick commented that they were near the scene at

the time of the abduction, Ferguson insisted that it was later or

earlier than that. Hedrick pointed out that he had paid with a credit

card at Brother's Bar, so the time that they left would be recorded.

Ferguson said, "Well, then you will just have to go with that."

Referring to the media attention over the abduction, Ferguson then

stated: "they're making a big thing out of this thing and it's just

another fucking cunt who lost it."

Ferguson was arrested later that night. After being

informed of his rights, both at the time of arrest and again at the

police station, he indicated he understood, and he agreed to talk to

Detective Michael Harvey. Ferguson admitted being at the Shell

station, across from the Mobil station, on the night of the abduction,

but he denied any involvement. Detective Harvey then placed the three

rings in front of Ferguson and told him that the rings had come from

an informant named Eddie who said that Ferguson had sold them to him.

Ferguson indicated that he knew that this was Ed Metcalf, but said

that Metcalf was lying.

The FBI crime laboratory examined blood, hair,

fiber, and DNA evidence collected during the investigation. The

serology unit tested blood samples from Kelli Hall, Ferguson, and

Kenneth Ousley, and the results showed that Ferguson had blood type A

and that he was a secretor, which meant that his blood type could be

identified from his semen. Ousley had blood type B, and was a

non-secretor. Tests of the vaginal swab and the vaginal wash taken

from Hall during the autopsy both identified semen that came from

someone with type A blood who was a secretor. Another test identified

semen collected from the collar and the inside of Hall's coat also as

that of an individual with type A blood who was a secretor. Lab

personnel then performed DNA analysis -- restriction fragment length

polymorphism (RFLP) -- by comparing DNA extracted from the semen stain

on the collar of Hall's coat with DNA extracted from blood samples

obtained from Ferguson, Ousley, and Hall. Based on these tests,

Ousley's DNA was not present in the semen stain, but the DNA obtained

from Ferguson was a "match."

Lab personnel also examined fibers found on Kelli

Hall's sweater and socks, compared them to fibers from the carpeting

in Ferguson's Blazer, and found them to be "indistinguishable." They

also examined a blonde hair of Caucasian origin found on Ousley's shoe

(Ousley is African-American), compared it with a sample of Hall's

hair, and determined that the hairs were "indistinguishable." Finally,

the pubic hair of an African American was recovered from Hall's socks,

and it was "indistinguishable" from Ousley's sample.

On the basis of the foregoing evidence, the jury

returned a verdict of guilty of murder in the first degree, and the

case proceeded to the penalty phase. To show Ferguson's prior

assaults, the state introduced the testimony of Holly Viehland, who

lived with Ferguson for two years, during which time Ferguson

assaulted her and frequently threatened to kill her. Additionally,

there was testimony that Ferguson shot an acquaintance, Mike Thompson,

in the shoulder during a dispute involving Viehland.

In mitigation, Ferguson presented testimony of two

clinical psychologists who testified that he suffered from persistent

recurrent depression and a psychiatric disorder known as substance

dependence, for which he never received adequate treatment. Ferguson

also presented eight other witnesses who testified to his problems

with alcohol and drugs and to his otherwise good character.

At the close of the penalty phase evidence, the

jury found the presence of the following six aggravating circumstances

beyond a reasonable doubt: 1) that the murder of the victim was

outrageously or wantonly vile, horrible or inhuman in that it involved

torture and depravity of mind, section 565.032.2(7), RSMo 1994; 2)

that the murder was committed for the purpose of avoiding, interfering

with, or preventing a lawful arrest of Ferguson or others, section

565.032.2(10), RSMo 1994; 3) that the murder was committed while

Ferguson was engaged in the perpetration or was aiding or encouraging

another person to perpetrate or attempt to perpetrate a felony of any

degree of rape, section 565.032.2(11), RSMo 1994; 4) that the murder

was committed while Ferguson was engaged in the perpetration or was

aiding or encouraging another person to perpetrate or attempt to

perpetrate a felony of any degree of kidnapping, section

565.032.2(11), RSMo 1994; 5) that Ferguson committed the crime of

assault against Mike Thompson on or about September 12, 1988

(non-statutory); and 6) that Ferguson committed the crime of assault

against Holly Utz from late 1987 to late 1988 (non-statutory). Upon

the jury's recommendation, the trial court sentenced Ferguson to

death. Ferguson timely filed a pro se Rule 29.15 motion, and counsel

then filed a 249-page amended motion. On February 25, 1999, the motion

court filed its findings of fact, conclusions of law, order and

judgment, denying all claims without a hearing and dismissing

Ferguson's motion in its entirety with prejudice. This consolidated

appeal followed.

II. ALLEGATIONS OF TRIAL COURT ERROR

A. Voir Dire

Ferguson claims that the trial court improperly

restricted death qualification voir dire by refusing to allow him to

ask the prospective jurors the following three questions regarding

their ability to consider mitigating factors in the penalty phase:

1) Can you imagine any mitigating factors that

would make you think that punishment for murder in the first degree

should be something other than the death penalty?

2) What kind of factors would you consider in

determining the correct punishment?

3) What sort of factors would you take into

consideration?

It is well-settled that the nature and extent of

questioning on voir dire is within the discretion of the trial judge,

and only a manifest abuse of discretion and a probability of prejudice

to the defendant will justify reversal. State v. Armentrout, 8 S.W.3d

99, 109 (Mo. banc 1999). Missouri courts have held time and again that

prohibiting open-ended questions like those asked here is a proper

exercise of the trial court's discretion. See, e.g., State v.

Middleton, 995 S.W.2d 443, 461 (Mo. banc 1999); State v. Thompson, 985

S.W.2d 779, 790 (Mo. banc 1999); State v. Chaney, 967 S.W.2d 47, 57

(Mo. banc 1998). The open-ended or over-broad questions in this case

have no reference to any pertinent mitigating circumstances, and

therefore, the information sought is irrelevant. See Middleton, 995

S.W.2d at 461. Furthermore, they are questions that appear to be

intended to elicit responses that would be more helpful in forming a

strategy for the penalty phase of trial, rather than merely exposing

disqualifying bias.

Even if the questions regarding mitigation should

have been allowed, Ferguson suffered no prejudice. The trial court did

not preclude defense counsel from exploring this line of questioning,

as long as he changed the form of the questions. In that respect,

defense counsel was permitted to ask each prospective juror

individually whether he or she would properly consider mitigating

circumstances that would justify a life sentence rather than the death

penalty.

Ferguson also argues the trial court erred in

sustaining objections to certain mitigating circumstances questions

asked of another prospective juror, Mr. Wilson. However, these

questions were potentially confusing, and therefore, improper, because

defense counsel had not set the context for the questions by

explaining the distinction between the guilt phase and the penalty

phase of the trial. State v. Thompson, 985 S.W.2d 779, 790 (Mo. banc

1999). Furthermore, Mr. Wilson was stricken for cause, and, for that

reason alone, Ferguson cannot now complain that he was unable to

expose Mr. Wilson's possible bias.

B. Guilt Phase

1. Admission of DNA Evidence

Ferguson alleges that the trial court erred in

admitting DNA evidence. Although Ferguson admits that the RFLP method

of DNA testing is generally accepted in the scientific community, he

contends that the procedures used by the FBI did not conform with

those required by the scientific community. Because Ferguson failed to

object to the admission of the DNA evidence, he seeks plain error

review under Rule 30.20, which requires a showing of manifest

injustice. The admission of the DNA evidence, however, was not

erroneous in the first place. This Court reaffirms its holding in

State v. Davis, 814 S.W.2d 593, 603 (Mo. banc 1991), cert. denied, 502

U.S. 1047 (1992), that the "argument concerning the manner in which

the [DNA] tests were conducted goes more to the credibility of the

witness and the weight of the evidence. . . " -- not to admissibility.

See also State v. Huchting, 927 S.W.2d 411, 417 (Mo. App. 1996); State

v. Davis, 860 S.W.2d 369, 374 (Mo. App. 1993). Ferguson's remedy is

not to exclude the evidence, but to cross-examine the state's experts

and to call expert witnesses of his own. The point is denied.

Next, Ferguson claims that the trial court erred in

admitting the DNA evidence because the state presented no evidence of

the statistical significance of its DNA test results, and the

characterization of the DNA comparison as a "match" is meaningless.

This theory was not presented to the trial court, and like the

previous claim, is only reviewable for plain error resulting in

manifest injustice. Rule 30.20. Scientific evidence, such as hair,

fiber, and blood type evidence, is often admitted where the only

conclusion to be drawn is that the tested sample is consistent with

the defendant's sample, or that defendant's sample shows that he

cannot be excluded as the perpetrator. Therefore, it was not error,

much less manifest injustice, to admit the testimony that Ferguson's

DNA "matched" that of the DNA extracted from the semen stain on Hall's

coat.

It bears mention that the absence of manifest

injustice is also shown by the fact that Ferguson had good reason to

avoid any inquiry about the statistical significance of the "match."

At Ferguson's first trial, the state's DNA expert testified that the

chances that the semen stain was from someone other than Ferguson were

1 in 1.7 million or 1 in 11 million, depending on the statistical

approach used. Although admission of that statistical evidence was

hotly contested, this Court did not reach the issue in the first

appeal, and therefore, neither Ferguson nor the state could be assured

of a favorable ruling before this Court the second time around. To

avoid the risk that the state would successfully introduce the more

damaging statistical evidence, Ferguson was justified, as a matter of

trial strategy, in declining to object to the less damaging

characterization that the evidence was a "match."

Finally, Ferguson contends that the DNA evidence

should not have been admitted because the semen sample was consumed in

the FBI's tests, and he was not able to have it independently tested.

In cases where the testing agency finds it necessary to consume the

only sample of evidence in the testing procedure, admission of the

test results does not violate due process in the absence of bad faith

on the part of the state. Arizona v. Youngblood, 488 U.S. 51, 57-58

(1988). Because Ferguson has failed to allege that the semen sample

was consumed in bad faith, this claim fails as well.

2. Admission of hearsay statements

Ferguson alleges that the trial court erred in

admitting hearsay evidence of Ousley's statements relating to the

attempted disposition of Kelli Hall's rings. These statements, as

noted, were admitted through the testimony of Alicia Medlock and Mike

Thompson. Thompson testified that on the day of the abduction Ousley

showed him two of the rings, explained that he and Ferguson "did a job

in St. Charles," and asked if he knew where to get money or drugs for

the rings. Alicia Medlock testified that within two days of the

abduction, Ousley and Thompson came to see her, and Ousley asked her

if she knew of a pawnshop or a place where he might exchange the rings

for drugs. The next day, Ousley told Thompson that Ferguson knew a

woman that would take the rings.

Statements of one conspirator are admissible

against another under the co-conspirator exception to the hearsay

rule, even if a conspiracy has not been charged. State v. Pizzella,

723 S.W.2d 384, 388 (Mo. banc 1987). For a statement to be admissible

under the co-conspirator exception, there must be a showing, by

evidence independent of the statement, of the existence of the

conspiracy, and in addition, the statement must have been made in

furtherance of the conspiracy. Id. The existence of a conspiracy need

not be shown by conclusive evidence and may be established, instead,

by circumstantial evidence consisting of the mere appearance of

"acting in concert." State v. Clay, 975 S.W.2d 121, 131 (Mo. banc

1998), cert. denied, 119 S. Ct. 834 (1999).

In this case, there was sufficient evidence that

Ferguson and Ousley were acting in concert in committing the crime.

The evidence placed both of them in Ferguson's Blazer at the scene of

the abduction. In addition, both were linked to the crime through

laboratory analysis: pubic hair found on Hall's body was consistent

with Ousley's pubic hair and hair found on Ousley's shoes was

consistent with Hall's hair; the DNA profile from the semen found on

Hall's coat matched Ferguson's DNA profile. Also, both men had

possession of one or more of Hall's rings at one time or another after

the abduction.

Ferguson argues, however, that Ousley's statements

were not made "in furtherance of the conspiracy" because the criminal

enterprise had ended. If, however, the conspiracy continues for any

purpose, such as concealing the crime, the declarations of one

co-conspirator are still admissible against the other. State v. Isa,

850 S.W.2d 876, 892 (Mo. banc 1993). Here, Ferguson and Ousley

continued to act together to eliminate evidence of their crime by

selling the rings. That their main objective was to dispose of

incriminating evidence is demonstrated by the fact that Ferguson

finally left the rings with Brenda Rosener, even though she had not

agreed to buy them. Under these circumstances, the statements were

properly admitted. Even if admission of the statements had been error,

Ferguson could not have been prejudiced because the jury learned

independently of his own attempts to sell the rings through the

testimony of Brenda Rosener and Ed Metcalf.

3. Sufficiency of Evidence

Ferguson next contends that there was insufficient

evidence to establish that he deliberated before the murder. He was

tried on a theory of accomplice liability. To convict him of murder in

the first degree, the jury had to find that he or Kenneth Ousley

knowingly caused the death of Kelli Hall after deliberation on the

matter. Section 565.020, RSMo 1986. Ferguson need not have personally

performed each act constituting the elements of the crime, State v.

Clay, 975 S.W.2d 121, 139 (Mo. banc 1998), cert. denied, 119 S. Ct.

834 (1999), but in order to be responsible for Ousley's acts, he must

have acted together with or aided Ousley either before or during the

commission of the crime, with the purpose of promoting the crime.

Section 562.041.1(2), RSMo 1986. In addition, where a defendant is

convicted of first degree murder as an accomplice, the state must

prove that the defendant personally deliberated upon the murder. State

v. Rouson, 961 S.W.2d 831, 841 (Mo. banc), cert. denied, 118 S. Ct.

2387 (1998). Deliberation is "cool reflection upon the matter for any

length of time, no matter how brief." Section 565.002(3), RSMo 1994.

Like any state of mind, deliberation generally must be proved through

the surrounding circumstances of the crime. State v. Johnston, 957

S.W.2d 734, 747 (Mo. banc 1997), cert. denied, 118 S. Ct. 1171 (1998).

Ferguson's more specific claim is that the only

evidence of deliberation is the manner in which Hall was killed and

that that particular evidence does not indicate Ferguson's personal

deliberation. Ferguson explains that an inference of personal

deliberation derived from the manner in which the victim was killed is

only appropriate where the defendant personally caused the victim's

death, State v. O'Brien, 857 S.W.2d 212, 219 (Mo. banc 1993), and in

this case, Ferguson's direct participation in the murder was not

established. This Court disagrees. The record shows that a white male

in a Blazer, identified as Ferguson's, was seen talking to Hall

immediately before she was abducted. The DNA in a semen stain found on

Hall's coat matched Ferguson's DNA. The body was partially covered by

steel partitions that Ousley, alone, could not have moved. A

reasonable juror could infer from this evidence that Ferguson intended

to abduct, rape, and rob the victim, and to murder her so that there

would be no witness. In fact, the evidence indicated that Ferguson was

the principal actor. Ferguson possessed a gun, and he appears to be

the one who first accosted Hall. The evidence that Ferguson raped her

was overwhelming. Further, Ferguson generally appeared to exercise a

significant degree of control over Ousley. Although Ousley was often

in Ferguson's company, Ferguson treated him poorly, referred to him as

"his nigger," and regularly required him to wait outside rather than

go with Ferguson into public places. On this record, the evidence was

sufficient to submit the charge of murder in the first degree to the

jury.

4. Instructions

Ferguson argues that the trial court plainly erred

in submitting Instruction 5, the verdict director for first-degree

murder, which was based on MAI-CR3d 304.04 and MAI-CR3d 313.02. This

instruction, Ferguson claims, misled the jury by allowing a finding of

guilt against him even if the evidence showed that only Ousley had

deliberated. Ferguson failed to properly object to this instruction

and is only entitled to plain error review on a showing of manifest

injustice. Rule 30.20. As this Court has repeatedly held, the alleged

deficiency in the verdict director is not error, plain or otherwise,

State v. Copeland, 928 S.W.2d 828, 848 (Mo. banc 1996), cert. denied,

519 U.S. 1126 (1997); State v. Richardson, 923 S.W.2d 301, 318 (Mo.

banc), cert. denied, 519 U.S. 972 (1996), and an extended discussion

on the point would have no precedential value. The point is denied.

5. Closing Argument

Ferguson contends the prosecutor made ten different

comments in guilt phase closing argument that constitute reversible

error. However, he made an objection to only one of the ten. The only

point preserved involved the prosecutor's discussion of the testimony

of Ferguson's expert witness, Dr. Libby. The prosecutor, while

reminding the jury of questions that he asked that witness, stated,

"And I said [to Dr. Libby], 'Do you remember Dr. Allen with the

Chapman Institute of Medical Genetics? He was a defense witness. Did

you ever discuss with him that he said all these bands matched?'"

Defense counsel then objected that "the witness said that he didn't

know what the other witness said," which was to say that the

prosecutor was misstating the evidence. The trial court responded that

"the jury will recall the evidence as they heard it."

The trial court has broad discretion in controlling

the scope of closing argument, and the court's rulings will be cause

for reversal only upon a showing of abuse of discretion resulting in

prejudice to the defendant. State v. Deck, 994 S.W.2d 527, 543 (Mo.

banc 1999). In this instance, the trial court did not abuse its

discretion in overruling the objection because the prosecutor had not

yet commented on Dr. Libby's response to his question, and for that

reason, the objection was premature. In fact, the prosecutor never did

follow-up and comment on Dr. Libby's response, even after the

objection was overruled.

The remaining allegedly improper comments, for

which Ferguson asks plain error review under the manifest injustice

standard, include: 1) "... if that's not cool deliberation, I don't

know what is . . . ;" 2) "[Brenda Rosener and Ed Metcalf] thought that

[Ferguson] was involved in this murder . . ." and that "We know that

Ed wasn't lying;" 3) "The jury should consider the personal emotional

impact on them;" 4) ". . . that's the way DNA is put on. It's not to

the degree of fingerprints, yet." 5) "[Defense witness Gamel] stated

[Ferguson] was 'slurring a little bit' [at the bar] and Hedrick stated

he 'staggered a little bit;'" 6) "This was a deliberate killing

because they tried to sell Hall's rings later;" 7) "A pubic hair on

Hall's sock 'matched' Ousley's;" 8) "The same guy that had the rings

matches the semen stain on her shoulder. The same guy that had the

rings matches the pubic hair on her sock out in that field;" and 9)

"[Ferguson] never looked at you and said, 'I didn't kill that girl.'"

Ferguson's laundry list of improprieties regarding

these statements include personalizing, bolstering, vouching for

witnesses' judgment and credibility, misstating the evidence, and

infringing on the right against self-incrimination. On review of the

record, each of the prosecutor's comments either have been taken out

of context or otherwise mischaracterized, and none of the remarks

constitutes error, much less manifest injustice.(FN1)

C. Penalty Phase

1. Denial of Request for Adjournment

Ferguson claims that the trial court erred in

denying his request to adjourn after the guilt phase verdict was

returned at 5:10 p.m. on October 23, 1995, and in proceeding with the

penalty phase case until 10:00 or 10:30 that night. He also claims the

trial court erred in denying his subsequent motion for mistrial, which

was based on the same grounds. In determining whether to grant a

recess or temporary adjournment during a trial, the trial court has

considerable discretion and will not be found to have abused its

discretion in the absence of a very strong showing of prejudice. State

v. Middleton, 995 S.W.2d 443, 464-65 (Mo. banc 1999). Here, Ferguson

contends that the members of the jury, having had a full day in court,

were too tired and aggravated to be attentive during the evening

session, and further, that trial counsel was too tired to proceed and

was unprepared to present the testimony of Ferguson's two penalty

phase expert witnesses.

These charges, however, are refuted by the record.

About 10:30 p.m., the trial court informed the jury that it was going

to save final argument for the next morning, and later made a record

that the jurors were disappointed because they wanted to finish the

case that night, which indicates, at the least, that the jurors were

not too tired or aggravated to listen to evidence up to that time. The

trial court's determination is also supported by the fact that the

jurors were sequestered and could not return home, which explains why

they were able and willing to proceed beyond the usual working hours.

In addition, trial counsel made no mention in her request for

adjournment or in the motion for mistrial that she, herself, was too

tired to proceed or unprepared to proceed, and her focus was solely on

her perceived adverse effect on the jurors. Even if counsel had based

the motion on her own fatigue and lack of preparation, there was no

prejudice. The record shows that counsel was able to elicit a wealth

of testimony in mitigation from the two experts, both psychologists,

that included the results of extensive psychological testing and the

diagnoses that Ferguson suffered from depression and substance

dependence. Their testimony supported, in particular, the statutory

mitigating circumstance that Ferguson's capacity "to appreciate the

criminality of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the

requirements of law was substantially impaired." The claim has no

merit.

2. Evidence of unadjudicated bad acts

Ferguson contends that the trial court plainly

erred in allowing the state to present evidence of unadjudicated bad

acts through the testimony of penalty phase witnesses Holly Viehland

and Mike Thompson without giving notice of the evidence prior to

trial. Because Ferguson did not object to this evidence, he must show

plain error under the manifest injustice standard. Rule 30.20.

Contrary to Ferguson's contention, he was clearly on notice that the

state would call Viehland and Thompson because the state called them

as witnesses during the penalty phase at Ferguson's first trial.

Although extensive evidence of a serious unconvicted crime is

inadmissible in the penalty phase if the state provides no timely

notice that it intends to introduce the evidence, it is not plain

error to introduce the evidence if it was introduced at an earlier

trial. State v. Chambers, 891 S.W.2d 93, 107 (Mo. banc 1994).

Ferguson also briefly alleges that the state failed

to comply with section 565.005, RSMo 1994, by failing to provide

notice of all the statutory aggravators that it intended to prove and

the witnesses it intended to call in the penalty phase. This claim,

however, is not in the Point Relied On in his brief, and, therefore,

it is not preserved for appellate review. In any event, Ferguson

cannot claim that he was prejudiced because all of the statutory

aggravators submitted to the jury in the second trial were disclosed

prior to the first trial.

Additionally, Ferguson claims in his point relied

on that the admission of unadjudicated bad acts in the penalty phase

(other than the two assaults that were specifically instructed on)

violates due process because the state is not required to prove those

acts beyond a reasonable doubt. Ferguson offers no argument in support

of the claim, probably because it has been repeatedly rejected by this

Court. State v. Kinder, 942 S.W.2d 313, 331 (Mo. banc 1996), cert.

denied, 118 S. Ct. 149 (1997). The point is denied.

3. Instructions

Ferguson next challenges the submission of

Instructions 16 and 17, the instructions for statutory and

nonstatutory aggravating circumstances, respectively.

The first of Ferguson's several reasons why the

trial court erred in submitting Instruction 16 is that the portion of

the instruction dealing with the first statutory aggravating

circumstance is unconstitutionally "vague and overbroad, applicable to

any murder and thus not narrowing the class of individuals to whom the

death penalty applies. . . ." The instruction states:

1. Whether the murder of Kelli Hall involved

torture and depravity of mind and whether, as a result thereof, the

murder was outrageously and wantonly vile, horrible, and inhuman. You

can make a determination of depravity of mind only if you find:

[1] That the defendant's selection of the person he

killed was random and without regard to the victim's identity and that

defendant's killing of Kelli Hall thereby exhibited a callous

disregard for the sanctity of all human life.

Ferguson specifically challenges the limiting

language of subsection [1] regarding the random selection of the

victim, the purpose of which is to comply with State v. Griffin, 756

S.W.2d 475, 490 (Mo. banc 1988), cert. denied, 490 U.S. 1113 (1989).

In Griffin, this Court held that, in order to avoid an arbitrary

application of the death penalty, the depravity of mind aggravator

must be supplemented by a finding of at least one of a number of

court-approved limiting factors. In State v. Brooks, 960 S.W.2d 479,

496 (Mo. banc 1997), cert. denied, 118 S. Ct. 2379 (1998), this Court

held that the random selection of the victim is to be included in this

list of limiting factors. Nonetheless, Ferguson claims that

subparagraph [1] "does not limit the class eligible for death or guide

discretion," because "a murder victim is always either someone unknown

to the defendant, as here, or known to the defendant. . . ." This

Court is at a loss to understand this argument. The fact that

Ferguson's selection of his victim was random demonstrates a callous

disregard for the sanctity of all human life. Therefore, requiring the

jury to find that Kelli Hall was chosen at random sufficiently

"narrows the depravity of mind aggravating circumstance to those

murders that involve an absence of any substantive motive." Brooks,

960 S.W.2d at 496.

Ferguson also argues that the randomness provision

of subsection [1] violates section 565.032.1(2), RSMo 1994, which

provides that the jury "shall not be instructed upon any specific

evidence which may be in aggravation or mitigation of punishment. . .

." However, Ferguson did not specify this reason to the trial court

when he objected to Instruction 16 during the instruction conference,

as required under Rule 28.03. As a result, Ferguson is only entitled

to plain error review under Rule 30.20 and must establish that the

trial judge so misdirected or failed to instruct the jury as to cause

manifest injustice. State v. Doolittle, 896 S.W.2d 27, 29 (Mo. banc

1995). Despite the statutory prohibition that jurors should not be

instructed on specific evidence of aggravation or mitigation, the

randomness provision serves to limit and thereby constitutionalize the

depravity of mind aggravator. For that reason, no manifest injustice

occurred.

Although Ferguson contends that there was no

evidence to support the submission of the second aggravating

circumstance -- "[w]hether the murder of Kelli Hall was committed for

the purpose of avoiding or preventing a lawful arrest of the defendant

or Kenneth Ousley" -- he couches his argument like that regarding the

first aggravator -- that the instruction does not sufficiently narrow

the field of those eligible for the death penalty. There is no

narrowing of the field, as Ferguson claims, because every murder can

be said to have been committed, at least in part, to avoid or prevent

the arrest of the perpetrator of the murder. This argument fails

because it ignores the logical inference that Kelli Hall was killed to

avoid Ferguson's and Ousley's arrest for kidnapping and rape.

Ferguson also challenges the submission of the

third and fifth aggravating circumstances instructions (no finding was

made on fourth aggravator), which state:

3. Whether the murder of Kelli Hall was committed

while the defendant was engaged in the perpetration of or the attempt

to perpetrate or was aiding or encouraging another to perpetrate or

the attempt to perpetrate a felony of any degree of rape.

***

5. Whether the murder of Kelli Hall was committed

while the defendant was engaged in the perpetration of or the attempt

to perpetrate or was aiding or encouraging another to perpetrate or

the attempt to perpetrate a felony of any degree of kidnapping.

Ferguson relies on State v. Isa, 850 S.W.2d 876,

902 (Mo. banc 1993), for the proposition that the phrase "aiding or

encouraging another" permitted the jury to sentence him to death for

Ousley's actions. This is another claim that has been repeatedly

denied. The incorporation of the phrase "aiding or encouraging

another," or similar language, "does not remove the jury's focus from

the 'convicted murderer's own character, record and individual mindset

as betrayed by [his] own conduct.'" State v. Hutchinson, 957 S.W.2d

757, 765 (Mo. banc 1997); State v. Gray, 887 S.W.2d 369, 387 (Mo. banc

1994).

Ferguson's complaint about Instruction 17, the

instruction on the two nonstatutory aggravating circumstances, is that

it also violates section 565.032.1's prohibition against instructing

on specific evidence of aggravators or mitigators. Again, Ferguson

failed to specify this reason to the trial court when he objected to

the instruction during the instruction conference. The claim is

reviewable only under the plain error/manifest injustice standard of

Rule 30.20. Ferguson offers no reason to believe that he suffered

manifest injustice because of this instruction, and this Court has

found none. The point is denied.

4. Closing Argument

Ferguson contends that 12 of the prosecutor's

statements in the state's penalty phase closing argument constitute

reversible error. Only five of these challenges were preserved for

appeal.

First, Ferguson claims that the prosecutor argued

facts not in evidence or misstated evidence when he said, "You know

what [Hall's] mother felt like then? Like her world had just dropped

out." Prosecutors may comment on the evidence and the reasonable

inferences to be drawn from the evidence, as long as they do not imply

knowledge of facts not before the jury. State v. Clemons, 946 S.W.2d

206, 228-29 (Mo. banc), cert. denied, 118 S. Ct. 416 (1997). Here, the

prosecutor did not improperly speculate, and, instead, merely stated

an obvious inference drawn from Kelli Hall's mother's testimony.

Next, Ferguson claims that the prosecutor

improperly speculated when he remarked, ". . . we don't know whether

he kept that ligature on or whether it was released and she started to

come to and he had to go back and do it again. You've seen those

marks." The trial court did not err by overruling the objection to

these statements, because they were drawn directly from the testimony

of the medical examiner.

Ferguson also claims that the prosecutor improperly

speculated and misstated the evidence by commenting:

What was going through her mind before she lost

consciousness? She knew she was never coming out of that field . . .

any begging out there fell and falls on deaf ears.

This comment was not objectionable because it was a

reasonable inference from the evidence.

The two remaining comments were challenged on the ground of improper

personalization. The prosecutor stated:

. . . no matter how long they had her out there,

have you thought during the course of the trial what was going through

her mind, how frightened she had to be?

***

. . . when you get back there and you start being

concerned about Jeff Ferguson and feel sorry for him, think about what

it was like out in that field that night.

A prosecutor "may recount in detail the victim's

pain and suffering, engendering sympathy in the jury during the

penalty-phase closing argument," and such argument is only improper

when it suggests a personal danger to the jury or their families.

State v. Rhodes, 988 S.W.2d 521, 528 (Mo. banc 1999). These comments

did not suggest such a personal danger, and therefore, the trial court

committed no error in overruling the objections.

Ferguson requests plain error review under the

manifest injustice standard for the following seven comments: 1)

"She's left out there for 13 days nude. There were marks on her neck.

You know that involved torture and depravity of mind;" 2) "He's

choking and beating other women;" 3) "I could have brought in Kelli

Hall's family. I could have put her mother up on the stand, tell us

about her childhood and have her cry. I could have brought her

grandparents in. . . . But I am not parading them in here to tell you

what a wonderful little girl she was and how much they are going to

miss her and that sort of thing;" 4) "You have to protect Kelli Hall.

We have to protect every child like her, ladies and gentlemen. Society

sometimes has to make tough decisions;" 5) "If any one of you had been

out in that field and saw what happened that night, like that you

would have known what has to be done in this case;" 6) "And it's time

for society to take a stand and take it against the people like Jeff

Ferguson who just manipulate and use people;" 7) "So I am asking you

on behalf of the State of Missouri, and on behalf of Kelli Hall's

family, to return a verdict of death in this case."

Ferguson alleges that these statements are improper

because they misstate the law or misstate the facts or they constitute

speculation or personalization. Upon review of the record, six of the

seven statements have either been mischaracterized or taken out of

context and were not erroneous, and like the claims regarding the

prosecutor's closing argument in guilt phase, most are frivolous. The

prosecutor did, however, make one misstatement of fact when he

commented that Ferguson was "choking and beating other women," and

Ferguson correctly points out that the state presented evidence that

he beat and choked only one woman other than Kelli Hall. This does not

amount to manifest injustice. The point is denied.

III. Allegations of Rule 29.15 Motion Court

Errors

Appellate review of a post-conviction motion is

limited to a determination of whether the findings of fact and

conclusions of law are "clearly erroneous." State v. Brown, 998 S.W.2d

531, 550 (Mo. banc 1999). Findings and conclusions are clearly

erroneous if, after a review of the entire record, the appellate court

is left with the definite and firm impression that a mistake has been

made. Id.

As noted, the motion court refused to grant an

evidentiary hearing on any of the claims in Ferguson's Rule 29.15

motion. The motion court need not hold an evidentiary hearing unless:

1) the movant cites facts, not conclusions, which if true would

entitle the movant to relief; 2) the factual allegations are not

refuted by the record; and 3) the matters complained of prejudiced the

movant. State v. Moss, 10 S.W.3d 508, 511 (Mo. banc 2000).

A. Disclosure

Several of Ferguson's Rule 29.15 claims arise from

the state's alleged failure to disclose exculpatory evidence before

and during the trial. Under Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83, 87 (1963),

due process requires the state to disclose evidence in its possession

that is favorable to the accused and material to guilt or punishment.

Evidence is material "if there is a reasonable probability that, had

the evidence been disclosed to the defense, the result of the

proceeding would have been different." United States v. Bagley, 473

U.S. 667, 682 (1985). More recently, the Supreme Court has held that

there are three components of a Brady violation: 1) the evidence at

issue must be favorable to the accused, either because it is

exculpatory or because it is impeaching; 2) the evidence must have

been suppressed by the state, either willfully or inadvertently; and

3) prejudice must have ensued. Strickler v. Greene, 119 S. Ct. 1936,

1948 (1999).

1. The surveillance videotape

Ferguson first claims that the motion court clearly

erred in denying a new trial or other post-conviction relief on the

ground that the state failed to disclose a surveillance videotape that

was supposedly made at the Mobil gas station on the night of Kelli

Hall's abduction. However, Ferguson failed to properly plead this

alleged Brady violation in his Rule 29.15 motion, asserting nothing

more than that the "state had in its possession material exculpatory

evidence that was not turned over to the defense," without specifying

what the exculpatory evidence might be. This allegation fails to cite

"facts, not conclusions, which if true would entitle the movant to

relief." Indeed, Ferguson conceded in the motion, itself, that he had

no facts to support the claim of withholding evidence. In State v.

Brooks, 960 S.W.2d 479, 500 (Mo. banc 1997), cert. denied, 118 S. Ct.

2379 (1998), this Court has made it clear that claims based on this

sort of pleading are unacceptable:

Appellant contended in his amended motion that the

state had in its possession material, exculpatory evidence that the

state failed to turn over to the defense. He sought to establish a

claim of violation of Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83, 83 S.Ct. 1194,

10 L.Ed.2d 215 (1963). Appellant's claim is patently frivolous. It is

entirely speculative and conclusional. There is no authority in law

for the proposition that a defendant may simply make a general

allegation of a Brady violation so as to require the motion court to

grant an evidentiary hearing and to order that the state discloses its

entire file so that a criminal defendant may cast about, attempting to

discover whether or not a Brady violation may have occurred.

Appellant's claim requires no further discussion.

In a related claim, Ferguson complains that the

state violated the motion court's discovery order to allow his counsel

to view the surveillance videotape. Discovery in post-conviction

relief cases, which are civil in nature, is governed by Rule 56.01, so

that Ferguson is entitled to "obtain discovery regarding any matter,

not privileged, which is relevant to the subject matter involved in

the pending action. . . ." Rule 56.01(b)(1). Despite the motion

court's order, the pleading defect in Ferguson's Brady claim -- the

failure to cite facts, not conclusions, that would entitled him to

relief -- foreclosed any entitlement to discovery on the matter. The

Brady violation was not actionable from the start and was ultimately

dismissed by the motion court for that reason, and therefore,

discovery sought pursuant to the Brady violation was never "relevant

to the subject matter involved in the pending action." To hold

otherwise -- to allow full-scale discovery on matters not properly

pled -- expands and distorts the post-conviction relief proceedings,

and Brady, itself, to something that was never intended.

Even if Ferguson had properly pled a Brady

violation, by the time he made his request for disclosure, which was

more than a year after the filing of his amended Rule 29.15 motion,

the videotape had been either lost or destroyed. Absent a showing of

bad faith on the part of the police or prosecutor, the failure to

preserve even potentially useful evidence does not constitute a denial

of due process. Arizona v. Youngblood, 488 U.S. 51, 58 (1988).

Ferguson has made no such showing, and the record discloses none.

Assuming that Ferguson had properly pled the Brady

claim, that he was entitled to discovery, and that the videotape had

been preserved, he still has not established that the evidence was

exculpatory or that prejudice resulted. According to Ferguson's theory

of the case, Mike Thompson and Kenneth Ousley were the actual

perpetrators. Witnesses had seen Kelli Hall talking with a white male

and a black male, possibly resembling Thompson and Ousley, who had

come to the station in a rusty Blazer between 9 and 10 p.m. on the

night of the abduction, and their presence at the gas station would

supposedly be borne out by the videotape. However, even if that

evidence appeared on the videotape, which is obviously a speculative

proposition, it does not in any way negate Ferguson's guilt. Ferguson

admitted he was with Ousley in the vicinity of the Mobil station at

about 11 p.m. when the abduction occurred, and therefore, he was still

fully capable of participating in the crimes. Even under Ferguson's

best case scenario, there is no reasonable probability that the result

of the trial would have been different.

2. The FBI materials

Ferguson next claims that the motion court clearly

erred in denying a new trial or other post-conviction relief based on

his claim that the state failed to disclose exculpatory evidence

pertaining to the FBI crime lab, including the FBI's entire file on

the case, and any and all information about the serology, DNA, and

hair and fiber units of the FBI lab. In addition, Ferguson makes the

related claims that the motion court erred 1) in denying several

motions to disclose a wide range of material that he asserted was

pertinent to the Brady violation and 2) in denying his motion for new

trial based on the FBI's failure to follow the motion court's order

that Dr. Libby be allowed to inspect its original DNA case file. These

claims fail for the same reasons the surveillance video claim fails --

the Brady violation was not properly pled in the Rule 29.15 motion and

discovery requests relating to the alleged Brady violations were thus

foreclosed.

Assuming Ferguson had properly pled the Brady

claim, he has not demonstrated that any of the FBI material would be

exculpatory or prejudicial. Before trial he was provided with

extensive information regarding the FBI tests and procedures, and he

used the information to thoroughly challenge the FBI evidence at

trial, as demonstrated, for example, by the 54 pages of transcript of

his cross-examination of the state's DNA expert. Ferguson does not

clearly identify what he hopes additional FBI materials would show,

and it appears that these materials, if any, could only be used to

counter the FBI evidence in basically the same way that he countered

that evidence at trial. Furthermore, it is worth noting that during

the post-conviction proceedings Ferguson was able to obtain through

the Freedom of Information Act at least 1,779 pages of FBI materials

that have still not revealed any more exculpatory information than

what he had before.

In denying relief, this Court is fully aware of

Ferguson's allegation and request for discovery regarding FBI Agent

Malone, who testified about the hair and fiber samples, and who has

apparently been exposed for falsifying testimony in other cases.

However, there is no evidence that Agent Malone acted improperly in

this case, and it cannot fairly be said that the hair and fiber

evidence had a prejudicial impact on the trial.

3. "South side rapist" materials

Ferguson argues that the motion court clearly erred

in denying his motion for disclosure of DNA materials from the "south

side rapist," an alleged serial rapist who was at large during the

time of Hall's abduction. Ferguson failed to include this argument in

his Point Relied On, and therefore, this Court's review is for plain

error/manifest injustice under Rule 30.20. State v. Tooley, 875 S.W.2d

110, 115 (Mo. banc 1994). Given the wholly speculative nature of the

underlying claim that the south side rapist might be the true

perpetrator, and the overwhelming evidence of Ferguson's guilt,

especially the fact that Ferguson's DNA matched the semen found on

Hall's clothing, no manifest injustice occurred. This claim fails for

the additional reason that it is a claim of newly discovered evidence,

which is not cognizable in a Rule 29.15 motion, even where properly

pleaded and preserved. State v. Stephan, 941 S.W.2d 669, 679 (Mo. App.

1997); Wilson v. State, 813 S.W.2d 833, 835 (Mo. banc 1991) (regarding

Rule 24.035 post-conviction claims).

B. Ineffective Assistance of Counsel Claims

Ferguson makes a number of claims of ineffective

assistance of counsel in his amended Rule 29.15 motion. To establish

that counsel was constitutionally ineffective, it must be shown that

counsel failed to exercise the customary skill and diligence that a

reasonably competent attorney would perform under similar

circumstances, and that the deficient performance prejudiced the

defendant. Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 687 (1984). In

order to obtain an evidentiary hearing, Ferguson must allege facts,

not refuted by the record, showing that counsel's performance did not

conform to the degree of skill, care, and diligence of a reasonably

competent attorney and that he was thereby prejudiced. State v. Jones,

979 S.W.2d 171, 180 (Mo. banc 1998), cert. denied, 119 S. Ct. 886

(1999).

1. Failure to move for a change of judge

Ferguson claims that counsel was ineffective for

failing to move for a change of judge based on the trial judge's

alleged bias toward criminal defendants. The basis for this claim is

that the trial judge received a "below average" rating on impartiality

in a 1992 Missouri Bar Judiciary Evaluation survey and that trial

counsel was aware that other public defenders were challenging the

judge's impartiality in State v. Smulls, 935 S.W.2d 9 (Mo. banc 1996),

cert. denied, 520 U.S. 1254 (1997).

This Court agrees with the motion court's finding

that neither the 1992 survey nor the fact that the public defender's

office had previously questioned and litigated the trial judge's

impartiality on various grounds constitute facts that would lead a

reasonable person to conclude that the trial judge was biased against

Ferguson. A general survey does not necessarily indicate that a judge

has prejudged issues in a particular case. Furthermore, the public

defenders in Smulls challenged the trial judge's impartiality by

alleging that he was biased against women and African-Americans, not

that he was biased against white males like Ferguson.

2. Voir dire

Ferguson presents two ineffective assistance of

counsel claims regarding voir dire: 1) that counsel should have moved

to strike prospective juror Schleper for cause; and 2) that counsel

should have moved to strike the entire group of prospective jurors who

heard juror Rohan's comment supporting the death penalty.

The claim pertaining to Mr. Schleper is that he

could not fully consider life imprisonment without the possibility of

parole. The motion court found that Ferguson's claim was refuted by

the record. This Court agrees. Although Mr. Schleper first indicated

that he "kind of . . . leaned toward" the death penalty, he then

stated unequivocally that he would consider mitigating circumstances,

would consider both possible penalties, and would follow the judge's

instructions. See State v. Ramsey, 864 S.W.2d 320, 336 (Mo. banc 1993)

(holding that the trial court did not err in overruling a challenge

for cause of a venireperson who stated that he "leaned toward the

death penalty"), cert. denied, 511 U.S. 1078 (1994). The ruling was

not clearly erroneous.

The second complaint involves prospective juror

Rohan's statement that "I am strongly for the death sentence. I would

have difficulty if I believed that someone murdered someone believing

that the country should support them the rest of their life." To

establish that the entire jury panel should have been quashed based on

one venireperson's statement, Ferguson must show that the statement

was "'so inflammatory and prejudicial that it can be said a right to a

fair trial has been infringed.'" State v. Smulls, 935 S.W.2d at 19

(quoting State v. Evans, 802 S.W.2d 507, 514 (Mo. banc 1991)).

Ferguson has not demonstrated that Ms. Rohan's statement was

inflammatory and prejudicial because there was no suggestion that

Ferguson, himself, deserved the death penalty, nor any attempt to

encourage other venirepersons to impose the death penalty. The ruling

was not clearly erroneous.

On this same point, Ferguson also contends that

after Ms. Rohan made the statement, counsel should have attempted to

educate the panel about the relative costs of life imprisonment and

the death penalty. However, this Court has held that such economic

concerns may not be addressed during voir dire, or at any time during

trial, because they are completely irrelevant to any issue before the

jury. State v. Clay, 975 S.W.2d 121, 142 (Mo. banc 1998), cert.

denied, 119 S. Ct. 834 (1999). Therefore, counsel was not ineffective

for failing to inform the jury on this information.

3. Guilt phase

a. Failure to investigate and present evidence

Ferguson claims that the motion court should have

granted a hearing on his claims of ineffective assistance of counsel

in the investigation and presentation of guilt phase evidence. This

claim is difficult to establish because neither the failure to call a

witness nor the failure to impeach a witness will constitute

ineffective assistance of counsel unless such action would have

provided a viable defense or changed the outcome of the trial. State

v. Hall, 982 S.W.2d 675, 687 (Mo. banc 1998), cert. denied, 119 S. Ct.

2034 (1999).

Ferguson is primarily critical of the failure to

present witness testimony or other evidence to impeach state's witness

Robert Stulce, who testified that he saw a brown and white Blazer that

looked just like Ferguson's at the Mobil station and that he saw Kelli

Hall get in the Blazer with a white male. Later, Stulce assisted

police in making composite pictures of the man he had seen. He also

viewed a police line-up that included Ferguson, and although he did

not positively identify Ferguson, he indicated that Ferguson and one

other man looked "similar" to the man he saw at the Mobil station.

Ferguson contends that counsel should have: 1)

introduced one of the composite pictures of the person Stulce saw

because it supposedly resembled Mel Hedrick more than Ferguson; 2)

introduced a picture of Hedrick taken close to the time to the

offense; 3) presented testimony that Hedrick did not have a beard at

that time, contrary to his testimony; 4) introduced Stulce's prior

inconsistent statement that the man he saw was a head taller than

Hall; and 5) introduced Stulce's prior statement that he was sure that

a man he later saw on I-70 was the man he saw at the Mobil station.

These actions, according to Ferguson, would not only have impeached

Stulce's testimony, but also would have linked Hedrick to the crime.

Impeaching Stulce's testimony either on

cross-examination or by calling other witnesses would not have aided

Ferguson. Stulce admitted that he could not identify the man he saw at

the Mobil station, and he did not identify Ferguson at trial. He

merely stated that the man looked "similar" to Ferguson. In addition,

Hedrick testified at trial so that the members of the jury were able

to see for themselves whether he had a resemblance to Ferguson and

could have been the man at the Mobil station. But even assuming that

counsel had done everything that Ferguson now suggests, and it had the

desired effect of leading the jury to believe that Hedrick was at the

Mobil station, it still would not have provided Ferguson with a viable

defense. None of this evidence would have shown that Ferguson was not

involved in the crimes.

Ferguson also faults counsel for failing to

investigate and present evidence that co-defendant Ousley, state's

witnesses Hedrick and Thompson, and even Kelli Hall and her boyfriend,

were involved in the area drug scene. The apparent purpose of the

evidence was to show that persons other than Ferguson had the motive

or opportunity to commit the crimes against Kelli. As the motion court

found, however, this evidence would have been inadmissible because it

constituted evidence of the witnesses' prior bad acts. State v. Clay,

975 S.W.2d at 141-43. It also would have been inadmissible because it

would not directly connect any of those persons with the corpus

delicti of the crime and point to someone other than Ferguson as the

guilty party. See State v. Rousan, 961 S.W.2d 831, 848 (Mo. banc

1998), cert. denied, 118 S. Ct. 2387 (1998). Finally, this is also the

kind of evidence that, even if it was admissible, is not inconsistent

with Ferguson's commission of every element of the crimes, as

principal or accomplice.

b. Juror misconduct

Ferguson contends in a cursory fashion that his

counsel was ineffective for failing to make a record that one of the

jurors was sleeping at trial and, thereafter, for failing to move to

strike that juror for cause. He also claims that the jurors committed

misconduct by disregarding the court's instructions to avoid news

reports and discussions of the case. He subsequently filed a "Motion

for Leave to Contact and Interview Petit Jurors" for discovery

purposes that was denied after argument.

The motion court did not clearly err in denying

these claims. In his Rule 29.15 motion, Ferguson did not allege

"facts, not conclusions, that would entitle him to relief," and there

is nothing in the post-conviction record to indicate that any juror

was actually sleeping. In addition, Ferguson failed to plead any facts

supporting his other claims of jury misconduct. The point is denied.

c. DNA and blood evidence

Ferguson also argues that counsel was ineffective

for failing to refute the state's DNA evidence. As noted, however,

Ferguson's trial counsel engaged in extensive cross-examination of the

state's DNA expert and called an expert witness for the defense, Dr.

Libby, who challenged the state's findings and procedures. Counsel was

not ineffective in this regard.

Ferguson next claims that counsel should have

insisted that blood samples be taken of Hall's boyfriend, Hedrick, and

Thompson because those persons may have been type A secretors like

Ferguson. This failure does not, however, show that counsel was

ineffective. Even if these persons were type A secretors, blood

evidence of that sort, which is found in a large percentage of the

population, had little to do with establishing the identity of the

perpetrator. Ferguson was convicted on the stronger evidence that his

DNA "matched" the DNA extracted from the sample on Hall's coat.

Ferguson further argues that counsel was

ineffective for failing to show that Ousley could not have been

excluded as the source of the semen on his own jeans. Again, Ferguson

cannot show that he was prejudiced. The state never disputed Ousley's

involvement, and, as previously discussed, implicating someone else,

especially Ousley, would not exonerate Ferguson.

Finally, Ferguson claims that counsel was

ineffective for failing to present evidence that his "judgment,

cognition and impulse control were substantially impaired" due to his

mental condition and consumption of alcohol. However, this evidence,

even if true, would have been inconsistent with his defense at trial.

Ferguson testified that he could not have committed the crime because

he "passed out" in the Blazer at the Shell station. Ineffective

assistance of counsel cannot be established where counsel pursued one

reasonable trial strategy to the exclusion of another. State v.

Harris, 870 S.W.2d 798, 816 (Mo. banc 1994), cert. denied, 513 U.S.

953 (1994).

d. The trial judge's efforts to expedite the

trial

Ferguson also claims that trial counsel was

ineffective for failing to preserve the challenge to the court

"forcing trial to proceed late at night" and for failing to preserve

his related motion for mistrial. The record shows, however, that

counsel adequately preserved these matters for this appeal.

In addition, Ferguson contends that trial counsel

was ineffective for failing to object and preserve a challenge to the

trial court's alleged efforts to expedite the entire course of the

trial. He alleges, in particular, that the trial judge hurried through

the trial so that he could go on a planned vacation. In support of the

allegation, he states: 1) that the trial judge commented to the jury

during voir dire that he intended to keep the trial moving along and

he intended to complete the trial within two weeks; 2) that the trial

judge allegedly remarked off the record that the case was interfering

with his vacation plans; and 3) that the judge's wife and friends were

present in the courtroom one day, apparently waiting for the trial to

end. This evidence, even if true, does not in and of itself

demonstrate trial court error. See State v. Engleman, 634 S.W.2d 466,

479 (Mo. banc 1982) ("the trial judge should act with the purpose of

maintaining orderly procedure and expediting the trial without denying

the defendant any right to which he is entitled under law.").

Moreover, Ferguson has not shown how he was prejudiced.

Assuming the trial court erred, Ferguson's

challenge still fails. In his Rule 29.15 motion, he did not claim

counsel was ineffective for failing to preserve this challenge, and

instead, he challenged the trial court's actions and rulings as a

matter of trial court error, which, as the motion court properly

determined, is not cognizable in a Rule 29.15 proceeding.

Nevertheless, Ferguson attempts to transform this claim of trial court

error into a cognizable ineffective assistance of counsel claim by

citing United States v. Cronic, 466 U.S. 648, 659-62 (1984), for the

proposition that external forces can render counsel constitutionally

ineffective even when counsel performed as well as a reasonably

competent attorney could have performed under the circumstances. This

is true, however, only when "the likelihood that any lawyer, even a

fully competent one, could provide effective assistance is so small

that a presumption of prejudice is appropriate without inquiry into

the actual conduct of the trial." Id. at 659-60. Here, such a

presumption is not appropriate. Even if Ferguson could overcome the

initial hurdle of demonstrating that counsel failed to exercise the

customary skill and diligence that a reasonably competent attorney

would perform under similar circumstances, he does not show that he

was prejudiced by the trial court's actions.

4. Penalty phase

a. Failure to investigate and present evidence

Ferguson claims that counsel was ineffective for

failing to investigate and present certain penalty phase evidence.

More specifically, he states that counsel should have presented three

expert witnesses, either in addition to or instead of the two expert

witnesses that were called. These three witnesses, according to

Ferguson, would have testified regarding the effect of his past and

present alcohol and drug addiction, his intelligence, his genetic

predisposition to a major depressive disorder, and his family history

of mental illness and alcoholism. Ferguson also contends that counsel

should have called twenty-six lay witnesses, in addition to the eight

lay witnesses that were actually called, to testify about his good

character and other mitigating circumstances in his background.

This additional evidence would have been

cumulative. The two experts who were called did testify, at length,

about Ferguson's intelligence, depression and substance abuse.

Further, the eight lay witnesses testified about his devotion to his

family, his good character, his problems with seizures, his problems

with drugs and alcohol, and other details about his background. This

was ample evidence in support of mitigation, and counsel's failure to

present additional evidence that would have been cumulative does not

amount to ineffective assistance of counsel. See State v. Johnston,

957 S.W.2d 734, 755 (Mo. banc 1997), cert. denied, 118 S. Ct. 1171

(1998). The point is denied.

b. Trial court's remarks at sentencing

Ferguson contends that trial counsel was

ineffective for failing to object to the trial court's derogatory

remarks at sentencing. These remarks included, "You deserve the death

penalty more than any case I've ever had in my life. And when I see

those pictures of that young woman, it even makes my blood boil a

little bit." Ferguson maintains that these remarks demonstrated a bias

and hostility toward him, although he does not state exactly what

relief trial counsel should have sought. Regardless, the motion court

did not clearly err in finding that the record did not support the

claim, and that Ferguson had not overcome the presumption that judges

do not consider improper evidence in sentencing. The judge's remarks

were made during, not before, pronouncement of the sentence and were

made to explain the sentence, and therefore, they do not establish

disqualifying bias. See State v. Whitfield, 939 S.W.2d 361, 368 (Mo.

banc), cert. denied, 118 S. Ct. 97 (1997). Furthermore, the trial

court's comments in this case are not unlike allegedly derogatory

comments in other cases that this Court held were not improper. See,

e.g., Haynes v. State, 937 S.W.2d 199, 201-02 (Mo. banc 1996).

5. Remaining ineffective assistance of counsel

claims

Ferguson's remaining allegations of ineffective

assistance counsel are based on claims discussed and denied in the

sections of this opinion dealing with trial court error. They include

that counsel was ineffective for failing to: 1) object and preserve

claims regarding the trial court's limitations on voir dire; 2)

challenge the admissibility of the DNA evidence; 3) object to the