How close was evil now? It

clung to him like sweat. Like the memory of that first murder... the

anticipation of the next. Here was Jim Greenhill, an adult, enthralled

of the mere boy locked in prison. Would he do the boy’s bidding like the

others have done?

Could he kill?

His name is Jim Greenhill. He

had run once before, but purposefully that time, when he left his native

England and wound up in Fort Myers, Florida.

He landed a job here as the

town’s crime reporter, the chronicler of evil. It was a grueling

existence. It was a long string of yellow crime scene tape.

Greenhill:

The reality is you’re always right up against a deadline. There are

always too many stories. There are always too few reporters.

It was a grind. What idealism

he once had had long since faded away. Gone was that naive sentiment

that inspired him to name his dogs Woodward and Bernstein, in honor of

the reporters who broke Watergate.

So at night, he’d escape. To

the Indigo Room, the Cottage, the Gator Lanes and the French Connection—one

Scotch drowning another.

Greenhill:

It’s a constant cycle of caffeine, nicotine and alcohol.

Too much caffeine. Too much nicotine. Too much alcohol and too little

protein and carbohydrates.

He had just entered his 30s. He

was jaded, numb, an alcoholic.

Strange, isn’t it, that when

you least expect it, you come across the thing that changes everything?

For Jim, it was Kevin Foster.

And who was he? He was the wild

boy – tough, masculine, a leader and a bully.

He was magnetic. For him, kids

would throw their lives away. But what about Jim, the adult? Could he

resist the boy-man Kevin? And his own demons too?

It all started in

April, 1996

The last day of school was just

around the corner at Riverdale High. For the senior class of ‘96, these

were those nostalgic moments, those final glory days.

That is, for almost everyone.

Pete Magnotti was a brilliant,

talented artist who dreamed of designing animation or comic books. But

he was small, weak, ostracized by the in-crowd. He poured his anger into

these violent sketches—his netherworld of fantasy.

His companion on the fringes of

high school society was Chris Black, a chunky computer geek. He was just

as smart, just as angry, and just as lonely.

They were seniors, good

students who never got in trouble. Graduation was less than a month away.

But these two would never make it. Within three weeks they’d be a story

for Jim Greenhill, from promising college material to Fort Myers’ most

notorious criminals.

They recalled those days before

graduation later from jail.

Chris Black:

All of us were pretty much at an impasse. Just... just

such a time of indecision there, nobody really knew where they truly

wanted to go. Everybody was trying to search for it. So everybody was

just in sort of like an intellectual limbo.

They were isolated. High school

society can be cruel. But then there was Kevin who seemed to know what

they were worth, who could make their fantasies real.

Pete Magnotti:

He’s really smart. He’s smarter than he lets on.

Pete and Chris worshipped Kevin

Foster. He was a drop-out and had given up on school— and yet, to these

boys, he was everything they could never be.

His house was a gathering

place. outcasts were welcome here. Kevin’s mother was more like a friend,

she and her son took the boys in like family.

Pete wrote in his journal:

“If you’re a person of small stature like me, it helps to have big

friends that have bigger guns that have a history of mental illness.”

Kevin was strong. Kevin was

wild. Kevin had guns.

Magnotti:

His parents had owned a pawn shop and sold lots of guns. He’s been

around the guns for his whole life. It was like toys to him.

Keith Morrison,

Dateline correspondent: How many did he have?

Magnotti:

Oh, he had lots. I don’t know specifically.

Morrison: 20, 25?

Magnotti:

Probably even more than that.

Kevin at 13, was holding a

Christmas gift from his mother—a 12 gauge pump action Mossberg shotgun.

As he grew older, his mother’s

pawnshop became a kind of private arsenal.

Magnotti:

He’d go that further step. He was just that much more exciting than

everyone else.

Morrison:

He’s prepared to be a little bit more bad.

Magnotti:

Yeah.

Morrison:

Little bit more dangerous.

Magnotti:

Mmm-hmm (affirms).

Morrison: And

that draws kids?

Magnotti:

At least us.

Yes, and the adult, too. The

reporter. But not yet. At the time Jim Greenhill was busy covering

accidents on the interstate.

It all changed on Friday night,

April 12. Kevin ordered Pete and Chris in his truck, and they went

driving.

Magnotti:

We stayed out all night, drove around in Kevin’s truck and whenever

the opportunity arose, we took it.

Black:

Devil’s night.

Magnotti:

Just a random spectacle of destruction.

In the dark woods, they smashed

car windows, broke into a gas station store, set a bus on fire. In the

back garden of a restaurant, they found two birds and burned them to

death.

A few days later, they

reconvened at Kevin’s garage. But it wasn’t just the three of them

anymore. Word had spread. They were six now.

Kevin, the leader, decided to

make order in the ranks. He gave them all one syllable code-names. There

was Slim, Fried, Mob, Red, Dog. And then he named himself.

Morrison:

He was “God.”

Magnotti:

Yeah. Thought it up himself.

Morrison:

Was it appropriate?

Magnotti:

That’s the way he thought of himself. He pictured himself in that

context. He was, you know, all powerful mighty being.

Someone came up with a name for

the group: Lords of Chaos. Pete sketched a logo.

They typed up a manifesto,

brimming with adolescent machismo. They wrote: “During the night of

April 12, the Lords of Chaos began a campaign against the world. Be

prepared for destruction of Biblical proportions. The games have just

begun, and terror shall ensue.”

As luck would have it on, those

very same days, Jim Greenhill was working on a related story.

Greenhill:

Some school principals had met and talked about what would happen if

they had a gang problem in the schools and how might they prevent that

and what would they—how would they deal with it.

It was dry, academic—a far cry

from the declaration of war brewing in Kevin’s garage. The Lords of

Chaos went unnoticed. Oh, they did send the manifesto to the newspaper.

But it never made it to Jim’s desk.

Only a small community paper

noticed the vandalism at all which it diminished as the acts of

“less-than-average intelligence,” carried out by “pea-brained vandals.”

Magnotti:

There was an article in the newspaper talking about uh, how, the

people who were doing things like that were just, uh, you know, stupid,

below average, uh, you know, simians—

Black:

—Below average intelligence. Simians—

Magnotti:

—Running around...

Black:

...Unorganized.

Morrison:

Pretty insulting.

Magnotti:

Yeah. We were really hurt by that.

Morrison:

Hurt?

Magnotti:

Well, you take a shot to the ego.

So the following Friday, The

Lords of Chaos decided to show the unsuspecting town what they could do.

Black:

"You want organized vandalism, we’ll give you some organized vandalism."

Magnotti:

Yeah, we can, uh, we can do something that’ll uh, take a little bit of

brains.

On one of the town’s main roads

stood a historical monument: an old Coca-Cola plant.

The Lords of Chaos broke into

two nearby hardware stores, stole propane gas tanks, opened them, and

then lit a fuse.

Black:

It was really theatrical, the whole angle that we were watching it

from.

Morrison:

How’d it feel?

Black:

Oh, it was majestic.

Magnotti:

It’s like look at us, we can wreak you know, whole loads of

destruction on whatever we want.

Black:

Right in full view of the public.

Greenhill:

I’m coming home from a friend’s house. I’ve been out late. I’ve been

drinking. And as I drive up McGregor Boulevard, there is thick smoke

hanging over the boulevard. And I go to where the smoke’s coming from.

And it turns out that the Coca-Cola building, which is a historic

building in Ft. Myers, has just—it appears blown up.

The fire made headlines.

But who did it? That remained a

mystery.

Alone, in his house, Kevin, the

mastermind of destruction, collected the articles Jim wrote. Police

would later find them on his desk. He liked them.

He told his followers it was

time for something bigger. Time to target a human being.

One of the boys knew about a

diner, where, every night at closing, the owner carried a bag of money

to his car.

Kevin made a plan. The Lords of

Chaos would ambush the man at gunpoint, steal his car, and take his

money.

The heist didn’t go quite as

planned. There was no bag of money and Kevin forgot Pete’s code name as

he screamed at him to get in the car and drive off. Frustrated, their

anger quickly turned to violence.

Morrison:

What’d you do to his car?

Black:

Uh, we trashed it. We beat it down for a while just to entertain

ourselves, get it out of our system.

Morrison:

Made some dents in it.

Black:

Oh, we made more than dents in it, We totaled it.

Morrison: But

you weren’t there?

Magnotti:

No.

Morrison: What

did you do?

Magnotti:

I went home. Um, I had a little curfew restriction with my parents. I

had to come home before 10. The supercriminal with a curfew.

Night was falling and the Lords

of Chaos had to go back to being teens again, obeying parents and

curfews and bedtimes.

For Jim, it was another night

at the Indigo room, the Cottage, the ‘Gator Lanes and the French

Connection. Another night of escaping.

Still outside the orbit of that

dark magnetic power. But in four days, someone would die. And Jim would

find himself in that elastic border between reality and the fantasies of

a teenage killer.

Tuesday, April 30th

Jim Greenhill’s beat was an

accident this time and another sad story—more police tape, more hours to

kill before the bars opened.

But fate is a strange business.

As Greenhill stood by the highway, not far away,

a murder plot was forming. In a few hours, one man would be dead and the

reporter would begin his strange tryst with evil.

Young boys, just weeks from

graduation, would have thrown their lives away all because of the

actions of one young man, barely a year older than them, but with

authority and charisma well beyond his years. Kevin Foster.

Keith Morrison,

Dateline correspondent: What sort of person is he?

Derek Shields:

Double personality, the way I looked at it. In front of

most people, he looks like an innocent little kid you know with

intelligence and all. If you see the dark side, he’s a psycho.

Derek Shields is in prison now,

but on that Tuesday afternoon he was an all-American boy, a member of

the high school band, his ambitions still intact.

But he was shy, too, an

outsider like Pete and Chris, like them in thrall of Kevin. And by day’s

end, his dreams would be over.

It was early evening now.

Riverdale High was alive. Mark Schwebes, the school’s music teacher and

band leader, was holding an open house, greeting next year’s freshmen

and prospective musicians.

Mark grew up here. He went off

to join the Marines and came back to teach. It’s all he ever wanted. He

liked his kids. He loved his music.

But as

the event was winding down, the Lords of Chaos circled the school.

Chris Black:

It was a whole big knot of people that night.

Pete Magnotti:

Yeah, we had about eight or nine of us that night. And, we decided

we’d go back to Riverdale and break some of the windows up. It didn’t

seem like a really big production. We had parked the cars across the

street, and uh, we were walking up to meet the rest of the group when

Schwebes pulled up and confronted Chris.

Black:

Everything went downhill from there.

The teacher had been heading

home when by this pay phone in the empty schoolyard he saw them: Chris

and one of the others looking suspicious,

wearing latex gloves, carrying heavy tin cans.

Morrison: What

was going through your mind when he came up and confronted you?

Black:

Everything’s... everything’s screwed up now. Everything’s all

screwed up, everything’s all messed up.

The teacher confiscated the

latex gloves and the cans, and told the kids to expect a call in the

morning. He threw the evidence in the back of his truck. Then he drove

off.

Black:

Nobody knew what to do. And so I threw something out there in the open,

an idea and everybody latched right onto it. “The man should be killed,”

no one disputed it. Everybody went for it. Group decision.

Morrison:

You said, he has to die?

Black:

Yes.

Morrison:

Did you think about it before you said it?

Black:

No.

Morrison:

You were upset?

Black:

Very angry. Very.

Morrison:

In a rage?

Black:

Oh yeah.

But Kevin was excited. A

process had begun. He and Chris called information and got the teacher’s

home address.

But now it was getting late.

Murder was in the air. But remember, these were boys. It was time to be

home.

Morrison:

Did you have a curfew that night?

Magnotti:

Uh, yes, 10 p.m. But uh, I stayed out, I didn’t follow it.

Morrison:

You decided I’ll brazen this one out because this is important?

Magnotti:

Because how many people can say, you know, "we killed a guy last

night"?

Some of the teens did leave.

Out in the night, Pete and

Chris went with Kevin to his house.

Morrison:

Where were his parents at that hour?

Magnotti:

Out, they’re, uh, really social. You know.

Derek—on the way to Kevin’s

house—had a crisis of conscience. What was he doing? He drove home,

pulled into his own driveway. Turned off the car and sat there. To go or

not to go? Mark Schwebes was his music teacher. He liked Mark Schwebes.

To go then, or not to go?

Derek pulled out of the

driveway and headed to Kevin’s.

Morrison:

Did you take him seriously?

Shields:

A little bit but not all the all the way. Not until we got to his

house he started pulling out the guns.

From the arsenal of guns in his

bedroom, Kevin picked the gun he got for Christmas when he was 13: the

Mossberg twelve gauge pump shotgun. And a silencer. And a map.

Magnotti:

Once we got the idea in our heads that we were going to kill somebody

tonight, it was just going to happen.

Derek watched. Excited? Or

anxious?

Morrison:

Why didn’t you leave then? I mean if there was ever a red flag for

God’s sake. You go to some guy’s house and he starts pulling out guns

and talking about killing a teacher who’s your teacher— why didn’t you

leave?

Shields:

I stayed to try to talk him out of it.

Morrison:

But he wasn’t paying attention to that was he?

Shields:

No. Eventually Kevin just blew up at me one time and just you know

grabbed his shotgun and told me you know shut up now or you know

somebody’s gonna die tonight if it’s not gonna be him it’ll be you.

So I shut up.

Morrison:

How were you feeling at that point?

Shields:

Very scared.

That night, as the reporter was

filing the story about the accident on the interstate, on that very same

road, four boys were in a car on their way to commit murder.

Morrison:

Didn’t take four people to do it.

Black:

No sir.

Magnotti:

Of course not.

Morrison:

So why’d you all go?

Magnotti:

Kevin needed an audience.

Black:

Mm-Hmmm (affirms).

Magnotti:

That’s the way I see it. If, he was by himself, he wouldn’t have done

it. He needs show everyone how tough he is. All the really bad things

he can do and not get caught.

As they approached the house,

Kevin finalized a plan: one of them would knock on the door. When the

teacher opened it, Kevin, hiding in the bushes would shoot.

But who would be the one to

knock? No one wanted to. Kevin gave the order: Derek will do it. Mark

Schwebes would recognize Derek from band practice if he looked through

the peephole. But Derek couldn’t move.

Morrison:

He didn’t want to go to the door?

Black:

No.

Magnotti:

He really really didn’t want to do it.

But Kevin ordered again.

Magnotti:

Kevin and Derek got out of the car. Me and Chris we waited in the car.

They walked around to the front of the house, and uh, they walked out

of our viewpoint.

Kevin hid in these bushes.

Derek approached this door and knocked.

He turned around. Kevin’s gun

was pointed straight at his face.

Shields:

I basically came face to face with the barrel of the shot gun. That’s

when everything it just felt like time slowed down everything got cold

and my mind just went blank. At the same time you know, it was only

matter of seconds, Scwebbes was uh, undoing the locks on his door. And

that’s when I spun back around and as soon as he opened the door he

you know it was like uh, “yes may I help you?” or something like that.

And that just totally flipped me out and I ran.

Morrison:

And then bang.

Shields:

Yeah. Two bangs from the gun.

Chris, sitting in the car,

staring at the dashboard, heard the first shot. Then the second. Why two?

Could Kevin have shot Derek? But then, two silhouettes came running

frantically toward the car.

Morrison:

Derek came first?

Black:

Derek was really screwed up.

Magnotti:

Yeah, Derek was, uh, shaking.

Shields:

At the time my mind was just flipping around. The next thing I

remember I just jumped in the car and just crawled up into a ball and

started shaking. Just repeating, “oh my god.”

The car took off. Kevin dropped

silent. Pete and Chris asked him: what happened?

Magnotti:

He was being real quiet because he didn’t want to disturb Derek. He

put his hand, you know, up to the mid section of his face, and uh, he

swept to the right and then he said, “Just gone.” You know, he was

implying that he just, you know, shot off the right side of the man’s

head.

Kevin told them the first shot

hit the teacher in the face. He fell to the ground in a fetal position.

Kevin aimed again and shot the buttocks.

Morrison:

How did you feel sitting in the car there once he’d come running out

and sat down and Derek was there shaking like a leaf and you’re

driving off as fast as you can.

Magnotti:

It...it didn’t really even really seem real to me. It seemed just like

I was, you know, watching myself from outside.

Driving into the night, Kevin

handed out cigarettes. He was elated.

Magnotti:

He was so proud of himself, so full of himself. He was like king of

the world, on top of the world, he could do whatever he wanted now.

And he just got away with like, you know, the worst thing you can do.

When Pete came home his mom was

waiting, angry. The boy missed his 10 p.m. curfew. But that night, Pete

was no longer a child. He walked past his mother and went to bed.

It was quiet that night in Fort

Myers. The ripples of that focused horror were just now spreading

outward.

And reporter Jim Greenhill was

blissfully unaware of the force that was already pulling him in.

The teens

get arrested

Jim Greenhill:

If you know about homicides in a community like Southwest

Florida, then you know that almost no one ever dies randomly. People

die in murders because they’re selling drugs, buying drugs, selling

themselves for sex or staying in an abusive relationship where there

have already been calls to the police. That’s why people get killed in

this region in the country. They don’t die because they go out and

answer their front door to someone and get shot dead. That doesn’t

happen.

Every crime reporter will tell

you about that one defining case of their lives. The night it happened

for Jim Greenhill, he was drunk in a bar.

Two people had called 911. At

11:35 a sheriff’s deputy was dispatched.

A crowd had gathered. The body

of a male Caucasian in his early 30s was lying in the doorway, welcome

mat soaked with blood. Shotgun-pellets were everywhere.

The investigation began.

Why two shots? Why in the

buttocks?

There was cash in his pockets

so robbery was unlikely. In the back of his truck, deputies found latex

gloves and an assortment of tin cans. Strange? Yes. But not much of lead.

Name of victim: Mark Schwebes.

A teacher.

That night, his sister, in

Atlanta, was awakened by a phone call.

Pat Dunbar:

My dad was crying. And he said, “Something’s happened to

Mark.” And I asked him “what?” And he said, “Mark’s dead.” And... I

tried to figure out, I asked him “Was it a car accident? What was it?”

And um, he told me he had been murdered. In his house.

At about the same time in Fort

Myers, another phone call was made: to Chris Burnett’s house.

Chris Burnett was one of

Kevin’s closest friends. Unlike Pete or Chris or Derek, Burnett was

Kevin’s peer—an equal, not a follower. They learned together... about

cigarettes, and cars, and girls.

He was there with Kevin the

night Mark Schwebes caught the Lords of Chaos by the school. But unlike

Kevin’s followers, Burnett was one of the boys who decided to leave.

Now it was kevin on the line.

He told Burnett: “It was done.”

Reporter Jim Greenhill arrived

at the scene of the crime early the next morning.

Greenhill:

I had gone to the house where the band director, Mark

Schwebes, had been killed. For a few seconds, it had crossed my mind—what

if it was kids from his own school? And I laughed at myself. I

remember laughing out loud because it just seemed so incredibly

improbable.

Sheriff John McDougall headed

the investigation. With little to go on, his deputies zeroed in on the

pellets lodged in the victim’s pelvis.

Sheriff John

McDougall: We call it a signature. When there’s any

sexual connotations in a homicide, we try to look at "why is that

there?" Was Mr. Schwebes involved in some kind of a love triangle?

That theory was the subject of

Jim’s front page story the next day.

Gossip from the teachers’

lounge leaked out: Mr. Schwebes was growing close to a teacher who was

breaking up from her boyfriend—was this some kind of love triangle

killing?

Kevin, the real killer, at home,

followed the coverage. He called his close friend Burnett and the other

teen who bailed out before the murder. He laughed: “Everybody in town is

so far off.”

Then Kevin called to brag to

two more boys. Told them what he did. Told them to keep it secret.

Pete Magnotti:

Foster got it into his head that you know, we can’t be touched, we,

you know, we’re free. There’s nothing else, no one can stop us.

Morrison:

No one even suspected you?

Magnotti:

Nope.

Black:

Mm-Hmmm.

But Kevin was wrong. Four boys

had committed a murder. At least four others knew about it. Who would be

the first to break?

Morrison:

A few days after the murder... you got a big boost?

Sheriff McDougall:

Yes. We did.

Morrison:

What happened?

Sheriff McDougall:

It was a girlfriend of one of the members of the Lords of Chaos that

had called us and said that her...her boyfriend had told her that he

had killed Mark Schwebes.

Julie Schuchard:

And he said, “Well I need to tell you something. He’s

like. “That was us. Or me.” Whatever. “We did it.” I’m like, “We? We

who?” And he’s like, “Me and Kevin.”

Two days after the murder,

Julie Schuchard's boyfriend confessed to her he killed the teacher. She

told her mom.

Schuchard:

She just stood still with like no expression on her face

like she didn’t know what to say.

Mother and daughter went to the

sheriff. And before long Julie’s boyfriend was hauled to the station.

Which one was he? Craig Lesh.

He was one of the boys who heard about the murder from Kevin.

He wasn’t even there.

In the interrogation room he

quickly confessed he had nothing to do with the murder. But he knew who

did: Pete Magnotti, Chris Black, Derek Shields, and Kevin Foster.

Kevin, the mastermind, at home,

oblivious to all this, decided it was safe. He would strike again.

Bigger this time.

Magnotti:

He wanted to do some kind of, you know, a movie...movie theatrical—

Black:

"Commando."

Magnotti:

--"Commando," "Delta Force" kind of thing.

His plan: an armed robbery of

the fast food restaurant where Pete and Derek worked.

And so the night arrived. It

was a Friday. Fort Myers was quiet. Unusually so.

The murder of the teacher was

now 72 hours old.

Pete and Chris filled a car

with guns and drove to pick up this boy, Brad Young, who heard about the

murder and wanted in on the gang.

Magnotti:

We pulled up to his house, we walked around behind his house and

the cops jumped down on us. That was it. It was over.

Black:

End of story.

Morrison:

No siren, no...

Magnotti:

No.

Black:

No siren no warning.

Morrison:

Pull over now?

Magnotti:

Mm-hmmm.

Black:

Flashlight in your face, gun to your back of your head. Face

against the wall. That’s, you know, when reality intrudes and you

know, you can’t deny me anymore, here I am.

Morrison:

Yeah.

Black:

Live with me, you’re screwed.

Deputies had been following

Pete and Chris that entire evening. Shortly after, the sheriff’s men

picked up Derek as well.

And a snake of deputy cars in

the night zeroed in on the mastermind. Kevin, with his best friend

Burnett in the car, was heading to the meet point when, at 8:45, a

sheriff’s car signaled for them to pull over.

“What to do?” Burnett asked.

“Pull over, I guess,” Kevin

answered.

In his last seconds of freedom,

Kevin turned to his friend and said: “See you in hell.”

Seven young men were brought to

interrogation rooms. Deputies raided their homes, confiscated their

computers, took their notebooks. And from Kevin’s house: more than 20

guns and rifles.

Jim Greenhill:

The telephone rings. It’s the sheriff. “Jim, I’ve been

trying to reach you. I’ve got this story.” He never does this. He

never does that.

The sheriff told the reporter:

you should see the gun show we’ve assembled down here.

But when Jim arrived at the

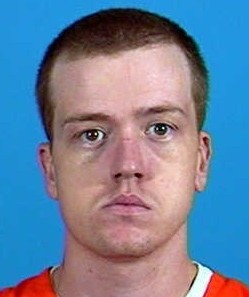

station, it wasn’t the 20 odd guns that struck him. It was a single

photo of the young man who had the guns in his house.

Greenhill:

Something happened the moment I see the photograph of Kevin with the

gun, because when I see the expression on Kevin’s face, I recognize

someone.

It was a suprisingly pure,

lonely memory. And it flooded Jim. That picture reminded the jaded,

alcoholic reporter of a boyhood friend he’d long forgotten.

Greenhill:

He was stronger than me, bigger than me—got away with more than me,

was way cooler than me. He was physically and mentally advanced for

his age—had the first experiences with girls out of anybody I knew—

And suddenly it all came back:

how in his youth, he says, he was pulled into strong friendships,

followed charismatic boys, boys like Kevin.

Greenhill:

Since my early teens, I had a tendency to be pulled towards kids who

were had a certain charisma to them. Who, perhaps, could fulfill some

things that I felt were a little lacking in my own life.

Of course that was long ago.

But that image would ignite passions long laid to rest, stir up emotions

long drowned by the bottle.

Among those arrested that night

were three who never made it to the teacher’s door. Brad Young, the new

gang member, was quickly released. He was not involved with the murder.

But then there were the two other boys. Yes, they left before the murder,

but they could face years in prison for just being there in the planning

stage. One of the two was Kevin’s best friend, Chris Burnett. Now he had

to choose: Freedom or friendship?

So Burnett turned on Kevin, his

close friend. He told investigators everything. This is part of his

statement:

Christopher Thomas

Burnett: He was saying how it was cool. He said the side of his face

just blew off. And then I shot him in the ass were his words.

Investigator: Who was with him?

Christopher Thomas

Burnett: Derek, Pete, Chris.

That statement to police opened

the door to more confessions. Right away, the second boy who left before

the murder took place, agreed to implicate Kevin Foster.

Investigator: Did Foster

describe how he shot him?

Tom Terrone: Yes. Just

did the, you know how you hold the gun straight and he just showed us

like that, boom, boom, boom.

In return for testifying in

full against the others, these two were promised lenient sentences. They

were out of custody soon after.

In the paper the next day Jim

quoted extensively from their confessions, their betrayal, as Kevin saw

it.

Derek, who stood closest to

Kevin when he pulled the trigger, now saw Kevin’s anger in jail.

Morrison: Did

you ever hear Kevin say, "somebody is gonna pay"?

Derek Shields:

Yes.

Morrison:

What did you hear?

Shields:

Right out of Kevin’s mouth telling me about how he, his mom was gonna

get some connections done they have Burnett, Terrone and Young

murdered.

Morrison:

Those are the three people who he thought as ratting you out.

Shields:

Yeah. They were the first ones that turned state.

Morrison:

And they didn’t have to go to jail.

Shields:

No.

Morrison:

So he was gonna see them killed.

Shields:

Yes.

Were the seeds planted for

another murder? Chris Burnett, once Kevin’s close friend, was out now: a

teen free to start living his life all over again. The price: handing

over his best friend to authorities.

Perhaps Burnett could forget

the man he helped put behind bars. But, behind bars, could Kevin forget

who was first to turn on him? It would become quite a murder plot. But

Jim Greenhill wouldn’t report that story. He was about to live it.

The trials of The Lords of Chaos

In sunny Fort Myers, the wheels of justice ground slow. It was almost

two years before The Lords of Chaos went to trial.

Reporter Jim Greenhill kept in

close touch with prosecutor Randall McGruther. McGruther was pursuing

the death penalty. This was a huge story for Jim’s newspaper.

Randy McGruther,

prosecutor: Jim had always been a good writer. Pretty

factual. He took great pains to confirm things before he, he would put

them in the paper. He called me several times on articles he was

writing about the Lords of Chaos to make sure that things were

accurate and he wasn’t overstating.

As the trial loomed, parents

and lawyers persuaded Pete, Chris and Derek, one by one, to testify

against Kevin and plead guilty to their roles in the murder plot in

return for being spared the death penalty.

In March 1998, Kevin Foster

stood trial alone.

And that’s where reporter Jim

Greenhill saw him for the first time in the flesh. But gone was that

charismatic grin. The defendant sat in court steel-faced.

Jim Greenhill:

[He was] not smiling not frowning, not moved by testimony,

not angry when his codefendants who struck plea bargains got up and

testified. Flat. Impenetrable.

But Jim Greenhill, sitting in

court, was transfixed. Unbeknownst to Kevin, he was already impacting

the reporter, who, no longer content to file short articles about this

case, left the paper and started working on a book about the Lords of

Chaos.

Jim sat in court listening to

the state’s evidence laid out by those who once called Kevin, “God.” The

same plot repeated over and over again.

Pete Magnotti: Mr.

Shields would knock on his door, Mr. Schwebes’ door. When he opened

the door Kevin Foster would shoot him with a shotgun.

All the stories matched—save

one. When Kevin’s mother, Ruby, took the stand she insisted her son was

with her that night, and he was innocent.

Ruby Foster, Kevin

Foster’s mother: My son did not do this. I do not want my son to die

for something he didn’t do.

Keith Morrison,

Dateline correspondent: What were your impressions of her?

Greenhill:

Somebody that was absolutely uh determined not to believe

in her son’s guilt.

Morrison:

She thought he was innocent honestly? Or she was just telling

herself?

Greenhill:

I can only give you my opinion. But I think that she, on

at least, on a conscious level, had convinced herself that he was

innocent.

She had fought to have her

son’s trial moved. Said Jim’s coverage had tainted the jury pool.

It was after all her demands

were finally denied that she finally confronted Jim face to face.

Greenhill:

I ran into her in the corridor and the first thing that she said to me

was, “I hate you.” Those were the first words that she said

Morrison:

"I hate you"?

Greenhill:

"I hate you."

The trial was short. Only three

days. Kevin Foster was convicted of first degree murder.

On April 10th, the

jury came back with a sentence, read by the judge.

Judge Anderson: For the

murder for Mark Schwebes, the defendant is hereby sentenced to death.

It is further ordered....

Randy McGruther:

Kevin Foster of course was convicted at trial sentenced

to death and is at Union Correctional in Starke, Florida, which is

death row.

Several months later the three

other “Lords of Chaos” learned their fate.

Randy McGruther:

Peter Magnotti was sentenced to 32 years in prison and he

is currently serving that sentence. Chris Black and Derek Shields were

each sentenced to life imprisonment and are serving those sentences in

the Florida state prison system.

Morrison:

How old are you?

Chris Black:

20 years old.

Morrison:

You will never see the outside of a prison.

Black:

Yes.

Morrison:

As long as you live. Do you think about things that you’ll never

have?

Magnotti:

All the time.

Black:

All the time.

Morrison:

Never have a wife, never have kids.

Black:

Never drive.

Magnotti:

Go to college.

Black:

Go to college.

Magnotti:

Fall in love.

Black:

Ride a bike.

Magnotti:

You wake up every day and you don’t have anything to look forward

to for the rest of your life.

Morrison: How

do you feel about that murder now?

Derek Shields:

I feel guilty about it.

Morrison:

Guilty?

Shields: Yeah.

like I should have done something to stop it.

All too late now. Corrections’

department vans had scattered the boys throughout Florida. And Fort

Myers resumed its languid normalcy.

But not Jim Greenhill. He

couldn’t stop thinking about the case. He reviewed the scores of

articles he had once filed about the Lords of Chaos. Still, he felt none

of those—even put together—could explain what happened, or why he cared

so much personally. It ate at him.

Greenhill:

I knew there was something unusual about it to me but I

wasn’t sure what it was. I couldn’t put my finger on it.

Jim must have assumed that the

key to the story lay in the past... if only he could grasp it. What he

didn’t grasp then was that the story was about to change, take a turn,

that it was no longer about the past—not about murders that had happened

but about killings to come.

The second half of this murder

mystery was yet to unfold. And the key lay in that one phrase Kevin

uttered to his best friend in his last minutes of freedom: “See you in

hell.”

How the reporter became part of the

story

Jim Greenhill had no idea what was to come: the Trial of the Lords of

Chaos was over. His trials had just begun. First: trying to become an

author. But harder still: trying to be sober.

Jim Greenhill:

I spent a great deal of time going to 12 step meetings.

And just sort of decompressing and limbering up for the task ahead.

And nights once spent at the

Indigo Room, the Cottage, The ‘Gator Lanes and the French Connection

were now dedicated to hour-long phone conversations with the murdered

teacher’s sister.

Greenhill:

At some point in that she said, “Jim, this is important

to you.” And I said, “Well yes, I’m writing a book about it.” And she

said, “No, there is more to it than that.” And I said, “Oh I don’t

know what you’re talking about kind of thing,” or, “I’ll have to think

about that,” or something. And I hung up the telephone and that’s when—that’s

when I remembered concretely thinking to myself, “You know, she’s

right.”

The sudden insight of a clear

memory long drowned in alcohol, lost from childhood.

It occurred to him that perhaps

looking into his fascination with the Lords of Chaos would mean finally

looking into that dark hole in himself—confronting demons he thought

defeated, urges he thought he’d overcome.

Greenhill:

And I decide that the first person to try to talk to is Kevin. Kevin

is the most important person in the story.

Kevin was on death row, in the

process of appealing his conviction. His mother, Ruby, was still in town.

But could Jim approach her? The last time they’d met she told Jim she

hated him.

Greenhill:

I called Ruby up and said, “Would you, and/or Kevin like

to talk me at this point?” And she said, “Yes.” And she said, in fact,

that she had been trying to reach me. And she had felt the time had

come to talk. She wanted to convince me of Kevin’s innocence.

Jim met Ruby several times in

that same house in which her son plotted murder two and a half years

earlier. And soon Jim started corresponding with Kevin.

Greenhill:

I went into it willing to listen to a completely

different side of the story.

And so letters began going back

and forth between the killer in the cell and the reporter on the outside.

“I know and God in heaven knows

I’m not a murderer,” Kevin wrote.

They wrote each other about

religion, morals, driving a truck on the open road. It was a tentative

relationship, but a growing one.

Finally, in March of 1999,

Kevin invited Jim to meet him face to face on death row. The jaded

reporter found himself feeling something he thought he had lost—excitement.

Greenhill:

There’s a very idealistic and I’m told naive side to me still. And I

really had this idea that I could go there and he would tell me the

truth. Whatever the truth was. And in learning the truth I would have

a better book. And it would help him somehow.

Jim coordinated the trip with

Ruby, Kevin’s mother. He was ready, but nervous. Two policemen he knew

from his reporting days told him to watch out—Kevin and Ruby come from

the pawnshop world, they are manipulative, they will get you to do

things.

Greenhill:

I had been warned these people are very manipulative.

They’re people who use people. They want to use you. And I was like "Well,

maybe. You know, I’m intelligent enough. They’re not gonna do that to

me."

But these two seemed to have an

eye for the outcast, the lonely, the fallible...to know how to draw them

in. In the upcoming months, mother and son would pull Jim closer, with

compliments, assurances of innocence, the intimacy of little secrets and

tender moments.

The reporter didn’t know it

then, but he was edging ever closer to a murderous plot of revenge—a

scheme that had him at its cold heart.

Letters

between Jim and Kevin -- a friendship forms

In 1996 a teenager named Kevin

Foster led a pack of young followers on a crime spree that ended in

murder. Now he was on death row. Three of the boys faced a life in

prison. Three others were trying to put that episode behind them. And a

reporter named Jim Greenhill believed he had a great book on his hands.

How could he know that the

murder of that school teacher, Mark Schwebes, would only be the first

half of his book? That he was about to become a character in a new plot

about murder—and that Kevin would have plans for him?

It’s an appropriate name for

the place where they keep Florida’s death row: Starke. This is where

Kevin was brought to live the rest of his life.

In March 1999, Jim met Kevin

face to face there for the first time.

He was struck by Kevin’s eyes.

They were not cold, as he remembered from court, but rather lost, even

pleading.

Kevin too seemed surprised, he

later wrote Jim: “It was a touch weird finally meeting you face to

face, you know? … I had pictured you as shorter and heavier than you

are. Most likely dressed like a preppy in Dockers and collared shirts...

But I have to say I’m impressed.”

Kind words. Was it gentle

seduction? Though initially it was Jim who sought Kevin, now it seemed

Kevin took equal interest in the budding friendship. Jim’s motive, at

least on the surface, was his book. What was Kevin’s? He kept

encouraging Jim to come back.

So Jim became a death row

regular, but not without commitment. It was a 5-hour drive from his

house to Kevin’s hell. He made most of the trips with Ruby, Kevin’s

mother. It was on the road Jim began to feel this was not a normal

relationship of mother and son. These two were a team. They accomplices

of sorts. They were almost, like, a couple.

Greenhill:

When they are together as a pair they have a relationship

that sometimes seems more boyfriend and girlfriend than mother and

son. The way that she holds on him. The way they touch each other. The

way they talk. And the things that they talk about... she talked about

looking into his room when he was in his bedroom with his girlfriend.

And watching him.

Why would Kevin and his mother

entertain this stranger, this reporter? Make him part of their intimate

group, of their weekend routines and family secrets? Was it to convince

him of Kevin’s innocence, or was something else afoot?

Kevin insisted he did not kill

the teacher. He said Derek did it, or maybe Burnett—his former best

friend, who cut a deal and handed Kevin to authorities. From meeting to

meeting, Kevin’s hatred towards Burnett seemed to grow.

But Kevin also showed Jim a

tender, sensitive side.

Kevin wrote:

“Kids my age, there is a growing number of them that

see life as a waste of time. A trip from womb to tomb and no matter

what you do it will always end the same. So why bother?”

Greenhill:

He is not a simple person. He is quite a complex person.

There is one level to him that is a sort of knee-jerk, adrenaline-fed,

impulsive, teenage vandalism— things for kicks. And then, there’s

another level that is extremely uncomfortable with the society that he

sees around him.

In tender letters, Kevin asked

Jim about missed opportunities. Girls he wanted to kiss but didn’t.

Authority figures he wanted to confront, but hadn’t.

Did Kevin realize how things he

said just kept echoing in Jim’s mind during those five-hour-long trips

back from prison each week? Could he tell just how much Jim grew to

relish these weekend visits?

Did Kevin know that—on weekdays,

between visits—Jim would go visit all those places Kevin rattled off in

their conversations? Did Kevin realize Jim was now trekking as far as

Alabama, Louisiana, Texas, like a disciple doing his homework?

Each location, each visit,

drawing him closer to the young man on death row. Meticulously, perhaps,

Kevin was building a bond, and drawing Jim in.

Greenhill:

Kevin has been raised to kind of form these very tight

relationships and bring people in and call them family members. So

that’s one of the things that he does.

Kevin told Jim how, for one

summer, he took care of a neighbor’s son who was dying of cancer.

Kevin wrote:

“I only regret that I didn’t have a chance to do more

for him. A good kid died for no reason.”

True, Jim was Kevin’s senior by

more than a decade, but it was in these moments that it seemed he came

under Kevin’s wing like so many others before him.

Greenhill:

He told me that he saw himself as a protector sometimes. That he liked

to look out for—well, specifically for Pete.

Kevin wrote:

“Pete didn’t have many friends… He didn’t want to be the small

scared kid anymore.”

Kevin emboldened Pete all the

way to murder. Was he preparing Jim for a mission too? Readying this

former alcoholic to join him, in friendship, in some fantasy? They were

still distant in age, but in spirit they grew closer and closer...

Greenhill:

When you’re a recovering alcoholic and addict you are to

some extent frozen at the age that you were at when you really started

using heavily. And you are sort of emotionally retarded. I’m still a

little back there in certain ways.

And Jim found it easy, even

comforting, to spill the intimate details of his life. And explain to a

man, just barely an adult, why, when he was that age, he started

drinking.

Greenhill:

I grew up in Britain, and I had parents who, I believe by American

standards, would be very strict. And I won a scholarship to go to

college in the United States. When I got to college, I had no parents.

No strictness at all, no structure. And I sort of devolved into

substance abuse and delinquency.

It all just poured out: stories

he buried in the back of his brain during all the years of drinking.

Greenhill:

There were incidents that in retrospect I can only describe just

purely as sociopathic incidents. I mean, just really, really appalling

behavior on my part.

He told Kevin that one time he

stood drunk just before dawn on a five lane highway going through his

college town, and fired an AK-47 into the air, and loved it.

So there it was. Kevin managed

to draw out of Jim confessions long drowned in alcohol, long dormant by

lulling adulthood. That Jim was turned on by violence.

Greenhill:

I told Kevin there were times when at a younger period in my life I

liked to go out and vandalize things… that I would just go out in the

middle of the night and vandalize things. Just for the fun of it. And

I didn’t need an audience. The day that I told him that he jumped up

from his seat and he goes, “Yeah.” He’s like really excited, “Yeah

you too, I like to do that too.”

Kevin wrote:

“I have very few friends. I can count them all on one hand and for

them I would do anything. You’re now one of them. For my friends I

would die.”

What would Jim do for his

friend? How could he know that Kevin may already have hatched a plan for

revenge.

And what would happen when

Kevin found out about the woman who would get in his way?

Jim Greenhill, once a crime

reporter—now a man obsessed by a killer—roamed and wandered—drawn to

someone else’s world.

His nights at the Indigo room,

the cottage, the ‘Gator Lanes and the French Connection now replaced by

pilgrimages to places like this on the dark side of town.

Jim Greenhill:

I had to walk in Kevin’s footsteps as far as I could in

order to understand Kevin. There is no other way to do it.

These were Kevin’s footsteps,

but where were they heading? And who was leading the way?

Was Kevin upping the ante now,

with gifts he now gave Jim? Items of clothing to make him look more like

him? A gold chain, a hoop earring, a black leather jacket?

Keith Morrison,

Dateline correspondent: You wore a leather jacket, he

asked you to wear?

Greenhill:

Yes. That, that I still don’t really understand that. He

asked me to wear this jacket. I did and I still don’t really get that

but I did.

Kevin encouraged Jim to send

photos of himself from the road.

Morrison:

There were those who felt as if you were falling in love with him.

That you were just falling for the guy. Was that...

Greenhill:

I haven’t heard that. I wouldn’t share that opinion…

Perhaps not as lovers, but it

was a tight bond Jim knew well. He had somehow become, in his own words,

a follower.

Greenhill:

There is a chemistry between somebody like Kevin and his

followers that can be mistaken by people viewing it from a distance as

perhaps, rather, like an amorous relationship or something. But I

think it’s psychological. I think it’s a psychological attraction.

But in Fort Myers, Florida,

there was something, and someone, who could have stood

in the way of Kevin’s plans.

In Fort Myers’ morgue, on a

warm spring night in 1996, came the body of Mark Schwebes. And here,

death after death, works this woman. Her name is Dr. Carol Huser. She is

the district medical examiner. She testified against Kevin in his trial.

She is also Mrs. Jim Greenhill.

Did she realize that night

after night her husband was pouring his heart out to a young man on

death row?

Morrison:

Was your husband falling for a psychopath?

Dr. Carol Huser:

Jim has an attraction for Kevin. I can understand that.

I’ve had powerful attractions to people though not a person like

Kevin. I think we all have different triggers. We all have different

things that appeal to us. I think what you’re looking at here is the

dark side of falling in love.

Jim never told Kevin about his

wife. It was Kevin’s mother who found out. And told her son, who,

furious, demanded an explanation.

He got it.

Privately, far from his wife’s

domain at the morgue, Jim told Kevin that his was a loveless marriage.

“She who must be obeyed,” as he called her, was oblivious to the secrets

the two were sharing. She was authoritarian, possessive, rigid, and

corporate. Jim spent hours complaining about her.

It was as though Jim wanted to

tell Kevin all... as though it were liberating.

Greenhill:

In theory, there is this side to me that is impulsive,

and wanting to do all these things and go out and be a certain kind of

person. How Kevin will help me is by bringing this out of me. He will

stop me from—doing what I’m doing, which is to repress and choke

myself by staying in a loveless marriage, and living in a corporate

world.

Was Jim becoming a character in

his own book? Did he realize it? Did Kevin?

Following Kevin’s footsteps

meant roaming from gun show to gun show across the south. It wasn’t long

before he bought a gun.

It had been years, since his

college days, that he shot one of these. He liked how it felt in his

hands.

Greenhill:

I was interested in what the attraction was. What the

appeal was. Kevin had guns from a very young age.

Morrison:

He loved them.

Greenhill:

He loved them, yes. I think it for him borders on a

sexual interest.

In the field behind his house,

he shot. Once. Again. And each pull of the trigger increased the strange

affinity he felt to the young man on death row.

And Kevin, quietly encouraged

Jim’s new found hobby. He arranged for his mother to lend Jim his

favorite gun. In a letter, he carefully explained how to clean the

prized possession.

Was he training his new recruit?

Jim wrote back:

“I borrowed the Colt finally. Man, I love that gun. I

love the weight of it and the look of it and its power, that it’s a

gun that means business in a way a .22 somehow isn’t, even though I

know that’s what the professionals use... the .22 just doesn’t seem

like a gun compared to your Colt, if you know what I mean. I also like

that it fits inside my waistband, in the small of my back or in front,

either way and I’m surprised by that. I wore it (I guess this is

taking a liberty, maybe, bro?) several times and it isn’t

uncomfortable to sit down with, nor to drive with. Nor did anyone seem

to notice anywhere. So I like it.”

In a letter, Jim told Kevin

about a violent dream he’d had. In it, Jim walked into a Victorian house

and slaughtered everyone inside.

“I have (vividly) killed

every single person in the house in their beds. I am going to escape

scot-free. Here’s the kicker: I do not experience this as a

nightmare. It is, just a dream.”

This was something Kevin

seemingly wished to explore. “What if you could pull three or four

capital cases in one day with no chance of getting caught?” he wrote.

What if you could get away with

murder?

And this was Jim’s reply:

murder would excite him. Sexually.

Jim's reply:

“There’s a quivering in my crotch. I stir down there,

involuntarily, just contemplating the question and I am quickly

aroused. But it’s more than that: I feel something in my arms, in my

hands, in my chest, in my whole body... and I recognize it as

adrenaline... it’s so strong I actually have a slight tremor at first.

My pulse increases. My breaths shorten. Most interesting to me, I am

about as fully aware of all around me the light, the breeze, the feel

of life—as I ever get. Now, this is NOT ‘normal’, bro. I know it ain’t.

I have lived with it (and repressed it and pretended it isn’t there)

since before my teens. And the only person I’ve ever told is you.”

They loved the same gun. They

exchanged similar violent fantasies. They even shared the same clothing.

Was it time now for Kevin to

launch the final salvo in the battle for Jim?

The subject of killing, of

murder, was discussed often, freely. But the actual murder, that which

landed Kevin on death row, was still taboo. That is, until one visit, 13

months into their relationship, when, Jim says, Kevin told him a secret

he had never shared with another adult before.

Greenhill:

He conceded that he killed Mark Schwebes.

Morrison: How did he put it?

Greenhill:

He started talking about the, the murder. He didn’t say, “I killed

Mark Schwebes.” It wasn’t quite like that. It was a given. He just

started talking about the murder.

But immediately after, Jim says,

Kevin told him another secret. Even darker. This was not something that

had happened. This was something that was going to happen: a plan.

Jim says Kevin wanted to

silence those who betrayed him after that murder. He wanted to punish

them. Especially his former best friend Chris Burnett—the first to hand

Kevin over to authorities. But how could Kevin do it from the depths of

death row?

Morrison:

Did you go out and buy guns?

Greenhill:

Yes.

Morrison:

Did you tell Kevin you would be willing to kill another human

being?

Greenhill:

Yes.

Morrison:

Did you tell Kevin that you would probably find some sexual

satisfaction from killing another human being?

Greenhill:

Yes, I did.

Here was a reporter who was

writing letters of fantasy about killing, saying he was a downtrodden

husband confessing violent dreams, a follower with a loaded gun.

Did Kevin groom the perfect

accomplice? Was Jim ready for murder?

Did Kevin

groom the perfect accomplice?

Jim Greenhill

reading his old letter: “I wish you were out. I was

born at the wrong time in the wrong place. It’d be awesome if I could

pick up the fucking phone and say “Hey, bro, I’ve got some ideas for

tonight, let’s go get it on. They ain’t seen nothing.”

Perhaps that was the wishful

thinking of a friend. But Kevin believed he could get out. He was

waiting for the results of an appeal. Hoping for a new trial, and

possibly even acquittal, but for one serious problem: six witnesses.

In a recorded conversation in

the noisy reception room of death row, Kevin told Jim that he should

have taken care of his accomplices Pete, Chris and Derek long ago, right

after he killed the teacher.

Kevin Foster (recorded

conversation): I should have wasted their whole fucking act that

night.

Greenhill: You’ve thought about that?

Foster: Oh man, so many

times. Dude, I had a f*ng 12 gauge and a 45. bam bam bam (laughs). The

only problem and the only reason I didn’t is the simple fact that

everybody knew who they hung out with.

Yet why worry about them now?

Locked away for life, what would they gain by testifying again in a new

trial?

But then there were others boys

who had heard from Kevin personally about the murder. Three of them cut

deals to testify against him, and were rewarded for their treachery with

freedom. How sweet revenge could be.

On June 11, 2000, his voice

sometimes muffled by the clatter of death row, Kevin laid out for Jim a

plan to kill the three who had betrayed him. Tell them you’re an author,

Kevin said.

Foster: You call all the

f*ck*rs up, you say “I’m so and so”... “I’ll give you a grand, come

hang out with me for a day, show me around.”

They would meet in an empty

parking lot, one at a time in hourly intervals. There, Jim would zap

them unconscious with a stun gun. Drive them to an open grave. And shoot

them.

Foster: You ain’t going

to be pumping 30 rounds... what you do when you do it, is you put it

against the f*cking flesh. Heart, head, either one.

Most of Kevin’s hate focused on

his former best friend Chris Burnett.

Kevin’s last words to Burnett

when they were caught were: “See you in hell.”

Now he seemed intent on

carrying out that promise. He planned Burnett’s execution down to the

last detail. Jim would shoot Burnett with Kevin’s favorite gun, a Colt

combat commander. And Jim would have to wear Kevin’s favorite necklace.

Greenhill:

And he wanted me to say, “See you in hell”—because he

wanted Chris to know that it came from Kevin.

On the night of June 25, Ruby

called. “I know what’s up,” Jim recalls Kevin’s mother saying. “He told

me everything.” She was in on the plan.

Ruby and Jim met in his truck,

outside a fast-food joint.

Greenhill: Did he say

anything about me borrowing his necklace?

Ruby Foster: Yes. He did.

Greenhill: All right, so

he told you everything?

Ruby Foster: Mm huh. You

think I don’t know everything, huh? (laugh)

Greenhill: He wanted me

to say something to him too.

Ruby Foster: Hmm. Do you

know what to say?

Greenhill: Yes.

Ruby Foster: Okay.

Greenhill: “See you in

hell.” (laughing)

Ruby Foster: “See you in

hell?”

Greenhill: He wants me

to say it and he wants him to see the chain so he knows who it came

from.

But there was a problem. Ruby

said Kevin’s favorite gun would be traceable. She came up with a better

plan.

Ruby Foster: My problem

was the gun item, that’s my biggest worry about the whole thing.

Jim Greenhill: That was

my—

Ruby Foster: I will get

you an unregistered off the street gun.

The following Saturday, Jim

says Ruby invited him to her house and gave him

a Remington Model 31, 16 gauge shotgun. In this tape, you can hear them

finalize a plan.

Greenhill: I’m gonna kill

Burnett first. I’m gonna do Burnett first, ‘cause he’s gonna be the

trouble. Torrone and Young are not gonna, they’re not gonna

Ruby Foster: Why are you

not getting Lesh?

Greenhill: ‘Cause, Kevin

doesn’t think that Lesh can testify.

Ruby Foster: But Kevin

will get him later?

Greenhill: That’s what

Kevin said.

Craig Lesh was the teen who, by

confessing to his girlfriend, brought down the Lords of Chaos.

In a meeting in Jim’s truck in

an empty parking lot, Ruby was adamant that this crime—unlike the

teacher’s murder—remain unsolved. She repeatedly told Jim to dispose of

any forensic evidence before leaving the murder site—things like shell

casings.

Ruby Foster: I don’t

care if you have to dig for them, you don’t leave those shells.

Greenhill: Okay, you got

it.

Ruby Foster: You swear

to me you won’t leave shells.

Greenhill: I absolutely

promise. I swear to God.

She also told Jim to sprinkle a

powerful chemical on the bodies.

Ruby Foster: Did he tell

you about you getting a bag of lye, lime?

Greenhill: No, he didn’t.

Ruby Foster: You do that,

then the animals won’t come and bother the hole and won’t dig it up.

And so the deal was done. The

crime reporter had turned partner-in-crime.

Greenhill: Now that we

don’t have any kind of barriers or anything, do you remember that time

you asked me like what gets me off or whatever?

Ruby Foster: Mm huh.

Greenhill: This is

pretty sick.

Ruby Foster: Sick?

Greenhill: Thinking

about Burnett kneeling at that hole in the ground ...

Ruby Foster: Mm huh.

Greenhill: ... right

before I shoot him.

Ruby Foster: Mm huh.

Greenhill: That’s what

gets me off.

Ruby Foster: How do you

know? You’ve never done it before.

Greenhill: No, you’re

right, but I’ve known for a long time, Ruby.

Before they parted the

conversation turned to the young man who had brought them here—to Kevin.

Greenhill: What are you

gonna do if they put him to death? I mean, that’s just unthinkable.

Ruby Foster: They’re not

gonna put him to death.

Greenhill: They better

not.

Ruby Foster: The world

will come to an end before he dies.

Greenhill: What do you

mean by that?

Ruby Foster: That’s none

of your business. Right at the moment your mother’s not gonna have to

tell you.

As the summer of 2000 was

nearing its end, Jim drove up to death row for the last time. In over 17

months, he and Kevin met 25 times, spending over 150 hours together.

Over that period Jim wrote Kevin 62 letters. Kevin wrote Jim 53.

Now, in what would be their

final moments together, Kevin promised Jim that once the second trial

was over, once he was free, they would team up

again: outlaws on the open road. And these three killings coming up,

these paltry necessity killings, they would be only the beginning.

Kevin Foster: I’m gonna

rip people’s f*ng’ heads off...

Greenhill: Oh yeah.

Kevin Foster: I’m going

to rip Craig Lesh’s head off with my bare hands (makes sounds). ...

I’m a twisted individual, you know what I’m saying?

Greenhill: Yeah, join

the club.

Kevin Foster: We got

some shit to do when I get out of this motherf****er. (laughs)

Four years earlier, a ring of

murder tightened around a teacher named Mark Schwebes. Now it was

tightening again. The plot had been hatched, revenge was in the air.

Everything was in place. But would Jim go through with it? And who would

the victim be?

Jim Greenhill talks to the authorities

Here, behind the pale green barricades of the penitentiary, from his

cell on death row, Jim Greenhill says Kevin Foster was cooking up a hit

list—and his mother was helping him.

And now the reporter himself

was involved too.

Marked for death were the three

key witnesses who had betrayed Kevin.

But they weren’t the only ones.

Also on Kevin’s hit list: the judge, the prosecutor, a defense lawyer...

even the sheriff.

Keith Morrison,

Dateline correspondent: What did they want to do to the

Sheriff?

Jim Greenhill:

Kevin said that he um, would like to gut him…

Morrison:

With a knife?

Greenhill:

Yes.

Morrison:

What did he want to do to your wife?

Greenhill:

He said that he would, if I would like it, he would like to go into

the morgue and conduct a, uh, live autopsy on her and, uh, perform

sexual acts on her.

Morrison:

On your wife?

Greenhill:

Yes.

Morrison:

What did you do when he said that?

Greenhill:

I actually didn’t react to him.

Morrison:

What did you think?

Greenhill:

Sick. [chuckles] Very sick. That’s what I thought.

Jim still liked Kevin. Kevin

was his friend. But to Jim, these were concrete plans for real murder.

This was not abstract fantasy anymore.

Greenhill:

Kevin said that he was going to blow up a historic

building. He did it. Kevin said, in the presence of a fairly large

group of teens, who should’ve known better and some of whom went home

and did nothing, that he was gonna go and kill their band director,

Mark Schwebes. He did it.

Now Jim found himself in

exactly the same spot as those boys who’d gotten in a car alongside

Kevin, on their way to murder. Would he go along too, surrendering his

judgment to follow Kevin?

Greenhill:

What I came to realize, working on the book, is that I

could’ve been sitting in the car. There was a period in my life when I

could’ve been one of these kids that got alongside a kid like Kevin

Foster and went along and watched somebody be killed.

But what to do now? It was now

up to Jim. He thought of Derek, the one boy who—almost grudgingly—walked

up to murder’s door and knocked.

Greenhill:

The night that Mark Schwebes was killed, Derek actually

drove home and he sat in his car at the end of his driveway and he

thought to himself, “Am I going to go to this murder scene? Are they

really going to kill my band director? What should I do?” For some

reason, Derek didn’t pick up a telephone and talk to someone.

But Jim was not a teenager. Not

a juvenile delinquent. And in the end, he was not a killer. Jim picked

up the phone.

Randy McGruther,

prosecutor: He was obviously concerned I could tell by

listening to him.

He called Randall McGruther,

the prosecutor in the original case, and told him everything:

McGruther:

He said that Kevin and, and his mother in fact had

plotted out a scheme to take care of some the witnesses in the case

and then along with other people uh, including the prosecutors. That

of course got my attention.

And so, Jim Greenhill—a

reporter turned author turned prospective hitman—agreed to turn state’s

witness and help investigators unravel the plot ripped out of his own

book.

McGruther:

I’m thinking I’ve been doing this 21 years and I thought

I’ve seen it all but I guess I haven’t.

And that is why when Jim met

Ruby next, in his truck outside the Walmart where she worked, he was

wearing a wire.

She suspected nothing,

presuming the conspiracy exclusive to their little group, like the Three

Musketeers.

Ruby Foster: It’s the

Three Musketeers only that know what’s going on and ever will know

what’s going on.

Her son was here, on death row.

How far would Ruby go to free him?

The story's end

Jim Greenhill was about to hand over his friend to authorities.

Jim Greenhill:

I did not talk to them after Kevin suggested this to me I talked to

them after his mother suggested this to me and that’s different.

Keith Morrison, Dateline correspondent:

Why?

Greenhill:

Because it is one thing for a 23-year-old convicted murderer on death

row in conditions of very high security to talk about doing something.

And it’s another thing for a person who is free, a 50-year-old adult

who is supposed to be a responsible member of society to talk about

doing something like that.

But didn’t Jim himself talk

about murderous fantasies? Jim now says he never meant to carry out any

of those dark plans. Today, he insists he never lost control. Quite the

opposite: The character teetering on the edge of murder was just that—a

character. A fiction created by a writer wanting to get to the heart of

his subject matter. It was a literary trick. A plot that would undo

Kevin, the master plotter himself.

Greenhill:

He does not open up to authority figures. So, I felt that it was

important to show Kevin that I could be on his level.

Morrison: Do you feel guilty?

Greenhill:

No. I don’t feel guilty. Kevin made his choices. Kevin

showed himself to me. And Kevin tried to use me. Um, the chips fell

where they may.

Morrison:

What, you’re using each other.

Greenhill:

In retrospect, I think that that he was using me as much or more than

I was using him.

But what would Jim’s wife say

to all this? The woman scorned in letter after letter—the woman on whom

Kevin wanted to perform what he called a live autopsy, as a gift to his

friend.

She says she supported her

husband all along. She says she knew about the whole thing.

Morrison:

He denigrated you at every turn, he vilified you he demonized you.

Dr. Carol Huser:

I thought he did it pretty well.

Morrison:

How do you come by this willingness to allow yourself to be used that

way?

Dr. Carol Huser:

I don’t really feel that I was used I feel that I was a

participant a willing participant even a partner.

Ruby Foster was arrested near

her workplace.

The alleged plot made the front

page of Jim’s former newspaper. The reporter was not writing the story

this time—now he was one of its main characters.

The day news broke, Kevin was

moved to even more strict confinement. He had no idea why. He wrote his

friend Jim what would be their last exchange: “I don’t know what’s going

on... I got transferred ... And don’t know why. Placed in this maximum

management lock-down... This is a cage in a box in a huge box in a huge

cage... Stay out of trouble, I’ll catch you next time. See ya!”

Several days later he found out

what going on: he’d be facing the same charges as his mother—conspiracy

to commit murder.

Morrison:

How do Kevin and his mother feel about you now?

Greenhill:

I don’t know. I haven’t talked to either one of them.

Morrison:

You, you must know.

Greenhill:

Uh, I, imagine.

Morrison:

You know them pretty well.

Greenhill:

I imagine that I’m on the top of the list.

Morrison: The kill list?

Greenhill:

Yes.

Ruby Foster was convicted of

conspiracy to commit murder. She was sentenced to five years in prison.

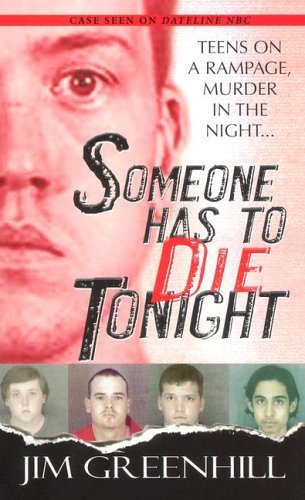

Jim,

the reporter, turned hitman, turned witness, finally turned author. His

book, titled “Someone has to Die Tonight,” was published.

It’s now up to readers to

decide who used whom—was it the reporter in control? Or the killer? Or

both? And who, if anyone, really fell for the other?

But in making your decision,

consider this: As Jim looks back on the final chapters of his tale,

those about the author who inserted himself into his own book, he says

he still wishes he could have changed the ending.

Greenhill:

In my fantasy world, frankly, I would’ve liked to have

stayed in touch with Kevin. I would’ve liked it if the book had come

out and I had portrayed him in such a way that he could recognize

himself and at least know that it was fair.

Jim used to have guns all over

his house, and always within reach... just in case Kevin tried somehow

to seek revenge.

He expects that one day he’ll

hear that Kevin has been executed for the murder of a teacher named Mark

Schwebes. Jim opposes the death penalty. But in his fantasy world, he

would like to be there the moment they pull the switch on Kevin. Not for

revenge. Not for anger. But for friendship.

Jim Greenhill’s book about

the Lords of Chaos, “Someone Has To Die Tonight” was published this year.

Kevin Foster remains on death row.