Hadley v State

1918 OK CR 83

175 P. 71

14 Okl.Cr. 644

Case Number: A-2900

Decided: 03/23/1918

Oklahoma Court of Criminal

Appeals

Appeal from

District Court, Muskogee County; Chas. G. Watts, Judge.

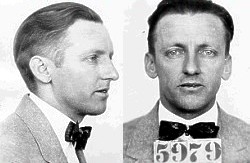

Paul V. Hadley

was convicted of murder, and he appeals. Affirmed.

P. A. Gavin, for

plaintiff in error.

R. McMillan,

Asst. Atty. Gen., for the State.

DOYLE, P. J. The

plaintiff in error, Paul V. Hadley, and Ida Hadley were jointly

charged with the murder of W. J. (Jacob) Giles, alleged to have been

committed in Muskogee county on or about the 24th day of March, 1916,

by shooting him with a pistol. Upon their trial the jury rendered

verdicts finding "the defendant Ida Hadley not guilty on account of

insanity," and finding "the defendant Paul V. Hadley guilty of the

crime of murder as charged in the information, and fix his punishment

at imprisonment in the state penitentiary at hard labor for life."

From the judgment rendered in pursuance of the verdict, the defendant

Paul V. Hadley appeals.

The evidence

shows:

That Paul V.

Hadley and Ida Hadley resided in Beaumont, Jefferson county, Tex. That

Paul V. Hadley was indicted for assault with intent to kill in

Jefferson county, Tex., and as a fugitive from justice was arrested

March 20, 1916, in Kansas City, Mo., where he was going under the name

of J. O. Kendrick. That W. J. (Jacob) Giles, sheriff of Jefferson

county, Tex., was notified of his arrest, and in the meantime Hadley

was incarcerated in what is known as the matron's department at the

police station. That while held there his wife, the defendant Ida

Hadley, visited him several times, and had several conversations with

him before Sheriff Giles arrived in Kansas City. That on the 23d day

of March, Sheriff Giles arrived in Kansas City with a requisition from

the Governor of Texas for Paul V. Hadley. That the defendant Ida

Hadley met Sheriff Giles at the police station and requested the

sheriff to allow her to return to Texas with her husband. That in

response to that request Sheriff Giles replied that she could come if

she wanted to, but she would have to pay her own railroad fare. That

she then gave the money to Mr. Sanderson, who was present, to purchase

a ticket for her, which he did. That Sheriff Giles, with both the

defendants, left Kansas City on a train called the "Katy Limited" at

5:30 p. m. on the 23d day of March, 1916, which train arrived in

Muskogee just after midnight the next morning. That before leaving

Kansas City, Ida Hadley requested Sheriff Giles to remove the

handcuffs from Paul V. Hadley, who had agreed to return to Texas with

Sheriff Giles by signing a written waiver of formal requisition. That

the sheriff did not grant her request. That when the train left

Parsons, Ida Hadley was sitting in the rear seat on the right side of

the chair car, and shortly after the sheriff, with Paul V. Hadley in

custody, came out of the smoking car into the chair car, where Hadley

sat down by his wife, and the sheriff sat down in the seat across the

aisle; that the defendants engaged in a whispered conversation, and

Ida Hadley went to the ladies' toilet in the front end of the car

several times, and each time returned to her seat by her husband. That

at that time the handcuffs had been removed from Hadley, and he was

riding just as any other passenger in company with his wife. That

Sheriff Giles at that time was sitting across the aisle in the third

seat from the rear, the back of which had been reversed, and he was

facing the defendants. That when the train left Muskogee, Ida Hadley

said to Sheriff Giles, "You might just as well go to sleep; Paul and I

are going to sleep in a minute"; that within ten minutes after leaving

Muskogee, Ida Hadley got up from her seat and walked to the ladies'

toilet in the forward end of the car; that after staying there a few

minutes she returned, carrying a satchel or package; that reaching the

sheriff, she drew a pistol from somewhere about her person, and shot

Sheriff Giles in the back of the head; that the bullet passed through

his head and fell on the floor; that the train at that time was

passing through the town of Oktaha, Muskogee county; that instantly

Paul V. Hadley jumped across the aisle and grabbed Sheriff Giles'

pistol and said to his wife, "Hold the gun on all of them; if they

move blow their heads off"; that Ida Hadley said to the other

passengers in the car, "Don't a man or woman of you get up"; that Paul

V. Hadley, after taking the sheriff's pistol, proceeded to go through

the pockets of the sheriff, taking papers out of his pockets and

sticking them into his own pockets; that about this time the train

auditor came into the car, and Paul V. Hadley, holding his pistol on

him, said, "Stop this train, God damn you, or I will blow your brains

out"; that the auditor pulled the bell cord, but the train did not

stop; that the Hadleys then went out on the front vestibule of the

car, and there kept their guns on the auditor, demanding that he stop

the train; that the train stopped at Checotah, and the two defendants

stepped off; that they walked about five miles south from Checotah and

stopped at the home of Mr. Ennis, and asked permission to stop there

until morning; that they also arranged to have Mr. Ennis' son drive

them to Briartown in the morning; that young Ennis started to drive

the defendants to Briartown or Porum; that after going about ten miles

he left them at Mr. Stevens' place on Hi Early Mountain; that, Sheriff

McCune, of McIntosh county, with a posse, arrested the defendants

there that forenoon; that Ida Hadley asked Sheriff McCune if Giles was

dead, and he told her he was, and she asked, "What are you going to do

with us?" and the sheriff said, "We are going to take you to Eufaula,

the county seat of the county where you killed this man"; the

defendant Paul V. Hadley then said, "I am in it just as much as she

is; just as much to blame as she." It appears that Sheriff Giles never

spoke after he was shot, and died two or three minutes after he was

taken from the train at Checotah. The defendant Paul V. Hadley did not

testify as a witness. The defendant Ida Hadley testified as a witness

in her own behalf and in behalf of her codefendant.

In rebuttal R. H.

Gaines, for the state, testified that he was in the hotel business at

Checotah, and was present with others there when Ida Hadley stated in

the presence of her husband, Paul V. Hadley:

"That her husband

had shot a man down in Texas; that she expected that some time he

would be arrested, and it was her intention to take him away from the

officers when they started back to Texas with him; that she had put

her gun in her grip, and had kept it there all the time since the

trouble in Texas; that when her husband was arrested in Kansas City

she asked Sheriff Giles' permission to accompany him back to Texas;

that her husband knew the gun was in the grip, and they had talked

this matter over several times--that is, the possibility of her taking

him away from the officer--and when they got to a little city above

here that had electric lights, a city of 15,000, 20,000, or possibly

30,000 people, she whispered to Mr. Hadley, 'When we leave this town I

am going to take Jake's gun off of him, and you get ready to make your

getaway.'"

And that she

further stated:

"I asked Giles to

lend me his drinking cup; he let me have the cup, and I started back

to the wash room; there I took the gun out and put it in my dress, and

I came out and down the aisle toward Mr. Hadley and Jake, and when I

got near Mr. Hadley I gave him a nod to get ready to get up; that she

and Mr. Hadley had frequently talked over the subject that she would

use the gun in taking him away from the officer-- that they had talked

it over after they left Kansas City while sitting in the car."

Other witnesses

testified that they were present when Ida Hadley made these statements

in the hotel at Checotah, and that at the time she and her husband

were handcuffed together.

The record is

voluminous, but the foregoing statement of facts is sufficient for the

purpose of this opinion.

It appears that

upon a sufficient showing that the defendant Paul V. Hadley was a poor

person, and by reason of his poverty unable to pay for the same, the

court ordered that he be furnished with a transcript of the testimony

and the proceedings had on the trial for the purpose of perfecting

this appeal, and for the same reason the petition with case-made was

filed in this court without cost. No brief has been filed, but the

defendant's counsel appeared and made an elaborate oral argument in

support of the only question presented by the record; that is, the

sufficiency of the evidence to support the verdict.

Upon a careful

reading of the testimony in the case, there can be no doubt that the

verdict of the jury is abundantly supported if they believed the

evidence given on the part of the state; that the jury did believe the

evidence on the part of the state is clearly established by the fact

that they found this defendant guilty.

The evidence for

the state showed or tended to show that the homicide was committed in

pursuance of an agreement or understanding between the Hadleys, and

that they conspired together to have the defendant, Paul V. Hadley,

make his escape from the officer having him in custody.

It is a rule of

law that when a conspiracy is entered into to commit a crime, all

persons who engage therein are responsible for all that is done in

pursuance thereof by any of their conspirators until the object for

which the conspiracy was entered into is fully accomplished. Grayson

v. State, 12 Okla. Crim. 226, 154 P. 334; Irvin v. State, 11 Okla.

Crim. 301, 146 P. 453.

Says Mr. Bishop:

"Since a combined

act and evil intent constitute crime, and since a thing which one does

through the agency of another is the same in law as though performed

by his personal volition, one who contributes his will to a crime, by

whomsoever the physical act of wrong is done, is guilty of the crime.

Hence, when two or more persons unite to accomplish a criminal object,

whether through the physical volition of one, or of all, proceeding

severally or collectively, each individual whose will contributes to

the wrongdoing is in law responsible for the whole, the same as though

performed by himself alone." (1 Bishop, New Crim. Law, sec. 629.)

We are satisfied,

from a careful examination of the record and of the proceedings had

upon the trial, with respect to fairness, that the defendant had a

fair and impartial trial. The charge of the court, to which no

objection was made or exception taken, was an elaborate exposition of

the law of the case. While the jury by their verdict acquitted the

defendant Ida Hadley, that was their peculiar province. No one can

tell what considerations enter into a verdict returned by a jury where

a woman is on trial. Nevertheless, if the jury made a mistake as to

her, that is no reason why this defendant should not suffer the just

penalty of the law. Upon the whole case we are satisfied that the

verdict was neither against the weight of the evidence nor against the

law.

Finding no error

in the record, the judgment appealed from is affirmed.

SEX: M RACE: W

TYPE: N MOTIVE: CE/Sex.

MO: Killed a

sheriff (Okla.) and married couple (Ariz.); several rapes.

DISPOSITION: 99

years (Okla.), 1916; escaped 1921; hanged Apr. 13, 1923.