By Joseph F. Sullivan - New York Times

December 1, 1990

On June 16, 1985, Nathaniel Harvey entered a

garden apartment in Plainsboro through an unlocked patio door.

In taking a watch and jewelry from a bedroom dresser, he woke

the tenant, Irene Schnaps. She hit him in the nose. He beat her

to death with a "hammer like" weapon, then choked her, a Medical

Examiner testified, for as long as an hour.

On Oct. 18, 1990, the New Jersey Supreme

Court overturned Mr. Harvey's death sentence, saying the jury in

his case should have been asked to decide whether he had

intended to kill Ms. Schnaps, or only to cause serious injury.

That decision, the 25th consecutive one in

which New Jersey's highest court overturned a death sentence,

prompted the state's Attorney General, Robert J. Del Tufo, to

issue an unusual public statement in which he said the court

appeared intent on preventing executions in New Jersey under any

circumstances.

Charging that the court's rulings had

undermined public confidence in the criminal justice system, he

stated, "If the court's underlying message is that it

philosophically objects to the death penalty, then it is time to

eliminate the charade and to reassess directly and expressly the

continued death penalty in the state."

Mr. Del Tufo's public criticism comes as the

Legislature is again preparing to take up the state's 1982

capital punishment law. Administration officials say Gov. Jim

Florio is also preparing to address the issue of an 8-year-old

death penalty that has yet to result in an execution.

A legislative committee will conduct hearings

in January and expects to release a new package of bills aimed

at streamlining the sentencing process in time for a vote before

the 1991 legislative elections, assuring the death penalty will

be an issue then, as it was in the governor's race in 1989.

The heart of the criticism by the Attorney

General, and by several county prosecutors, is a belief that

inconsistencies in the court's rulings suggest that the justices

will turn in any direction to reverse a death sentence. They are

particularly concerned by the court's emphasis on determining

the intent of killers.

The New Jersey court, regarded by legal

experts and academics as one of the leading state courts in the

nation, has not responded to the criticisms from Mr. Del Tufo,

county prosecutors or members of the Legislature. Carl Golden,

the court's spokesman, said, "The court, as always, will let its

opinions speak for themselves."

Supporters of the court, including the New

Jersey Public Advocate's office, counter that reversals occurred

when trial judges and prosecutors did a poor job of preparing to

try capital cases, and then committed errors that have required

action by the high court.

Dale Jones, the assistant public defender who

oversees the defense of all condemned prisoners, said that, in

contrast, his office took a crash course when it became apparent

the law would be enacted.

"We traveled around the country to states

that already had the death penalty, and learned how trials are

conducted," he said. "There was no similar preparation by the

prosecutors or the courts."

But a deputy attorney general who has

supervised capital cases, Boris Moczula, said prosecutors are

becoming cynical. They believe, he said, that if there are no

other grounds to overturn the death penalty, the Supreme Court

turns to the question of intent -- whether a person intended to

kill, or only to inflict serious injury which then led to death

-- to find a way to order a new sentencing hearing. Series of

Rulings

In one case, overturned because of a judge's

error in instructing the jury, the court said that the

defendant, an armed robber who shot a convenience-store cashier

three times, obviously intended to kill his victim.

But in another, in which a man chased his

victim, dropped him with a shot in the leg and then stood over

him and fired two more shots into his head and back, the court

said the intent was unclear. It ruled that the jury should have

been asked to decide whether the gunman meant to kill.

The issue of intent was first raised in 1987,

when the high court upheld the death-penalty law. The sole

dissenter, Justice Alan B. Handler, complained about the

"extraordinary" range of defendants who would be subject to the

death penalty, because state law defined murder as both

"purposely and knowingly causing death" and "purposely and

knowingly causing serious bodily injury that leads to death."

The next year, in reviewing the case of

Walter Gerald, the court ruled that the New Jersey Constitution

allowed the execution only of people who had intended to kill,

not those who meant to inflict serious injury.

In doing so, the court departed from the

United States Supreme Court, which has said that people who

exhibit a "reckless indifference to human life" in causing death

can be subjected to the death penalty.

Mr. Gerald had beaten to death a 55-year-old

man during a robbery by stomping on him and hitting him in the

head with a television set. Split Decisions

Following the Gerald decision, the court

overturned several death sentences, saying that if there is any

doubt about a defendant's state of mind, a judge in a capital

case must require a jury to decide the question of intent.

Mr. Moczula and others point to reversal of

the death sentence in the case of Kevin Jackson as one that

strains the meaning of intent. Mr. Jackson pleaded guilty in

1986 to stabbing a 51-year-old female neighbor 53 times.

Since the Gerald decision, some members of

the court have also been unhappy about how it has been applied.

In the cases of Frank Pennington, who was convicted of shooting

a bartender to death, and Ronald Long, convicted of fatally

shooting a liquor store owner, the decisions to overturn the

death sentences and send them back for new sentencing hearings

came on 4-to-3 votes.

Mr. Jones, the public defender, said: "It's

not hard for anyone to be troubled by the Gerald decision, and I

understand the frustration of prosecutors, but I believe the

Supreme Court made the right call, and it was very difficult

call to make." 'Not Your Average Joe'

He pointed out that Mr. Jackson, for instance,

was high on drugs when he stabbed his neighbor. "That's the

situation in many of these cases," he said. "That and the fact

that some of the defendants suffer from diminished mental

capacity. These are the people who wind up on death row, not

your average Joe on the street."

Mr. Jones said the Legislature and the public

as a whole also do not understand the pace of death penalty

litigation, which takes an average of 12 years, including

Federal appeals, from indictment to execution.

Senator John F. Russo, a Democrat of Toms

River and chief sponsor of the 1982 law, agreed. "People forget

t took 8 to 14 years for an execution under our old law," he

said.

Mr. Russo said he intended the death penalty

to be imposed for only the most egregious intentional murders,

and added that he believes the court has been unfairly

criticized for its ruling in the Harvey case.

"I've read the decision and the court didn't

say Harvey didn't intend to kill his victim, it said the

question of intent was one for the jury," he said. "I have no

problem with that."

Is New Jersey

Poised to Execute an Innocent Man?

Fighting for His Life

By Laura Masnerus

May 15, 2005 - The New York Times

Plainsboro, New Jersey

IRENE SCHNAPS, a 37-year-old widow, was found

dead on a June day in 1985 in the blood-splashed bedroom of her

garden apartment here, and within days a man in her life became

a suspect.

The man was a neighbor whose name, Pete,

appeared often on Ms. Schnaps's personal calendar, although her

friends told the police she considered him a pest. Investigators

questioned him for hours, administered a lie-detector test and

took some of his belongings that appeared to have bloodstains.

But a few months later - still without enough

evidence for an arrest - the police in West Windsor Township

found another suspect, a burglar who confessed to a rape in the

area. They charged him with Ms. Schnaps's murder, and their case

would prove all but unshakable.

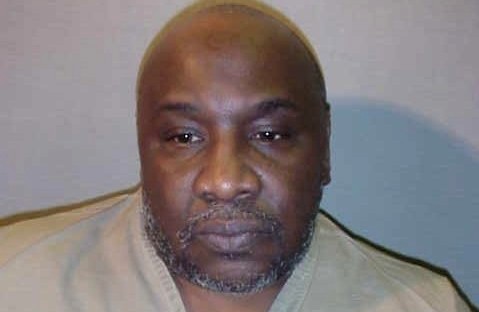

Twenty years later, that suspect, Nathaniel

Harvey, is on death row at the New Jersey State Prison in

Trenton. He tells his lawyer to make sure the remaining evidence

in his case is preserved even if he is executed. Someday, he

says, it will show that he did not kill Ms. Schnaps.

With new information about that evidence,

which a lower court recently refused to hear, Mr. Harvey's case

will now go before the New Jersey Supreme Court, probably next

year. While the court takes great pains with all death-penalty

cases, Mr. Harvey's is different from the other 10 on death row

and, indeed, presents a claim that the court has not heard in

decades: that the state plans to execute the wrong man.

Middlesex County prosecutors say the claim is

outlandish. They contend that Mr. Harvey's guilt was

demonstrated by, among other things, a confession and by DNA

evidence from Ms. Schnaps's bedroom, evidence that was accepted

by jurors and ratified by courts, including the state Supreme

Court - not once but twice.

But Mr. Harvey has always insisted that he

never confessed. And now the lawyer who took his case five years

ago, Eric V. Kleiner, has unearthed evidence of a flawed

investigation, contaminated evidence, false testimony and

potentially fatal mistakes by defense lawyers. Mr. Kleiner

contends that the DNA evidence was badly botched, an error with

the perverse stamp of scientific certainty. He also obtained the

original suspect's polygraph results; the jury and the Supreme

Court were told that the man had passed, but he had in fact

failed decisively.

"This stuff is so egregious," Mr. Kleiner

said. "If they knew then what we have now, everything would be

different."

That protest - if they knew - has brought the

release of more inmates from death rows around the nation, 83

since 1989, than legal experts in the pre-DNA world thought

possible. In Mr. Harvey's case the prosecution is fiercely

contesting the claims of new evidence, and last month the state

Superior Court - the trial-level court that has presided over Mr.

Harvey's habeas corpus challenge for five years - refused his

request for a new evidentiary hearing and dismissed the case.

Now the Supreme Court faces the question of

how much doubt is reasonable doubt, what evidence is truly new

evidence, and how DNA testing might unravel decisions that were

official truths years ago.

Mr. Kleiner was appointed by the public

defender's office mainly because of his expertise in DNA testing.

A voluble, intense man with a solo practice in Englewood Cliffs,

he began tugging at other strings, pried thousands more pages of

documents from the prosecutors, brought in his own experts and

ended up tearing the case apart.

The defense also built a case against the

initial suspect, accusing him of murdering not just Ms. Schnaps

but another woman in the area. And he wants more testing,

including DNA tests on items taken from the man's car 20 years

ago, to see if Irene Schnaps's blood is on them.

While Mr. Kleiner has accused prosecutors of

withholding and destroying evidence, they have accused him of

concocting conspiracy theories, demanding irrelevant evidence

and slandering an innocent man. Julia McClure, the first

assistant prosecutor, declined to be interviewed but said in an

e-mail message that testing the old evidence "would not yield

material results."

"It's absolutely indefensible," Mr. Kleiner

said. "It is not seeking answers to questions that are

unresolved. It's the best evidence we have left, and there's no

justifiable explanation for wanting to put somebody to death

without looking at it."

The evidence was also a problem for one

former State Supreme Court justice, Alan B. Handler, who

dissented emphatically when the justices upheld Mr. Harvey's

conviction in 1997. Justice Handler, now retired, routinely

dissented in death-penalty cases, but his objections in Mr.

Harvey's case were unusually specific, including a 64-page

analysis of the DNA testing. Looking to the habeas challenges

sure to follow, he wrote, "I have little doubt that when the

time comes, this case will eventually be reversed by this court

or a federal court."

Colleague Finds the Body

Ms. Schnaps's body was found by a worried co-worker

who went to her apartment, in a development called Hunter's Glen,

when his colleague - widowed for 10 weeks and living alone - did

not show up for work at the nearby RCA offices.

It was a Monday afternoon, June 17, 1985, and

Ms. Schnaps had died Saturday night or early Sunday morning.

Neighbors had heard nothing unusual, but Ms. Schnaps's bedroom

was horribly bloodied. Her body was nude and her head battered

by what investigators termed a "blunt metallic instrument." A

pillowcase on the floor bore part of a bloody footprint.

The police found boxes for a camera and a

Seiko watch, but the crime did not seem to be an aborted

burglary. There was no sign of forced entry, and the killer had

left valuables behind. Next to the body was an empty cassette

recorder - a clue that made more sense when her friends said Ms.

Schnaps, a stenographer, kept a diary on tapes.

As neighbors gathered, a man from the next

building named Peter Stohwasser volunteered to the police that

he saw Ms. Schnaps often. Mr. Stohwasser, 41 and divorced, said

that he had asked her out but that she said she was not

interested in a sexual relationship so soon after her husband's

death; he told her he would wait. He told the police they went

out for Chinese food the week before she died.

From Ms. Schnaps's friends the police learned

that a neighbor named Pete was constantly at her door, and on

her calendar, which served as a diary of sorts, the name "Pete"

appeared often. (The next-to-last reference, on May 18, said, "Turned

Pete down," and a week later she wrote, "Party w/Pete.") The

police also learned that Mr. Stohwasser had served time in jail

for stalking and threatening a girlfriend.

Mr. Stohwasser told the police he was home

Saturday night and did laundry Sunday morning, then talked to Ms.

Schnaps on the phone. They had not disclosed the time of death,

and, suspicious of the discrepancy, asked him to take a

polygraph. He failed many questions, including the crucial one:

"Did you murder Irene?"

Investigators then got a search warrant and

took a quilt that appeared to contain bloodstains from his

apartment; from his car, they took a pair of white work gloves

and a metal strip, both with small reddish spots.

Five days after the murder, the police took

sheets and clothes, apparently washed but containing reddish

stains, that had sat unclaimed in the common laundry room.

Tests on Mr. Stohwasser's quilt found human

blood. Hairs were retrieved from his quilt, too, and examined

along with the hairs collected from Ms. Schnaps's bedroom. The

lab concluded that all of the hairs appeared to match the

victim's.

In some ways, though, the evidence was not

adding up. The shoeprint was too small for Mr. Stohwasser's size-12

foot. Lab reports on the gloves and metal strip from his car

said blood was "not detected."

It is hard to tell exactly what the

investigators knew in the fall of 1985, because many of the

laboratory notes and worksheets are missing. At some point, an

expert told prosecutors the shoeprint was probably made by a

Pony sneaker. And while all the hair collected from the murder

scene was originally designated Caucasian, a lab worker added

this line: "and one negroid hair." The date was not noted.

The police found Mr. Harvey on Oct. 28,

fleeing from a series of burglaries and, in the course of one of

them, the attempted kidnapping of a 13-year-old girl. Mr. Harvey,

34, was the answer to a string of unsolved break-ins - the

short, stocky black man described by several homeowners - and he

quickly admitted these.

He was also wearing Pony sneakers, in a small

size. His criminal record included a sexual assault, and after

more questioning he admitted to a recent unsolved rape.

Mr. Harvey insisted that he had nothing to do

with the Schnaps murder. "I been thinking a little while here,

in all my life I never killed anytime," he told detectives as he

twisted in his chair against tight handcuffs.

But a search of his car turned up a Seiko

Lasalle watch, minus the band, like the one that was apparently

missing from Ms. Schnaps's apartment. And after almost three

days of questioning, the police reported, Mr. Harvey confessed.

The confession was not recorded or put in

writing. But the two detectives who interrogated him said Mr.

Harvey told them he entered Ms. Schnaps's apartment and killed

her after she awakened and punched him in the nose.

Mr. Kleiner argues that the investigators'

initial suspicion was right: that Ms. Schnaps's killing was more

brutal, more personal, than a surprised burglar would inflict.

But Thomas Kapsak, the prosecutor who handled

the investigation, said Mr. Stohwasser was not a killer, either.

"He was one of those guys who hung around the

pool with gold necklaces trying to pick up women," Mr. Kapsak

recalled.

Within days of Mr. Harvey's arrest, Mr.

Kapsak authorized the return of Mr. Stohwasser's quilt.

"I was the A-number-one suspect," Mr.

Stohwasser, now 61 and living not far from Hunter's Glen with

his second wife, recalled in an interview this month. "And then

one day I heard they arrested this guy, and it was over."

His account differs in places from the one he

gave 20 years ago - he now says he and Ms. Schnaps never went

out to dinner, for example - but he says, as he did then, that

he was asking her out and getting nowhere.

He said he did see her the weekend of her

death: "The only reason they came after me - and I don't know

why I failed the polygraph, probably because I was nervous - was

that I said I was probably the last person who saw her alive."

He denied talking to her on the phone that weekend, as he had

told the police, but acknowledged at another point in the

interview that he might have.

Mr. Stohwasser also remembered the items

taken from his apartment and car. He said the quilt did have

blood on it, "from another girl I was seeing at the time" -

although police reports show that the woman said a year earlier,

when she accused him of stalking her, that their affair was over.

'Questioned and Questioned'

"I was questioned and questioned and

questioned," he said, until the day he heard on the radio that

another suspect had been found with items that linked him to the

Schnaps murder.

He added, "I'm surprised they're still going

after this."

Mr. Harvey declined to be interviewed for

this article; Mr. Kleiner says that after 20 years on death row,

his client barely communicates with anyone, and when last tested,

in 1979, his I.Q. was 66. In a statement conveyed by Mr. Kleiner,

Mr. Harvey said that he regretted his crimes but that "I have

never murdered anyone."

Mr. Harvey has always been that adamant.

During the second trial he was offered a plea deal for 30 years

without eligibility for parole, which would have added no time

to the sentence he was already facing for other crimes, but he

turned it down.

When Mr. Harvey stood trial in 1986, the

defense had very little. If he had an alibi for the night of

June 15, it never came to light. His lawyer did not call any

expert witnesses. And Peter Stohwasser's name never came up.

Mr. Harvey was convicted and sentenced to

death, but in 1990 the State Supreme Court granted him a new

trial. The court held, among other things, that the confession

was inadmissible because the detectives did not give adequate

Miranda warnings.

The second trial was a battle of experts over

the blood evidence, by this time tested for DNA. Mr. Harvey was

again convicted and sentenced to death, and the Supreme Court

upheld the conviction in 1997.

Mr. Kleiner's review of the 15-year

prosecution began with the damning blood evidence. The samples

are degraded now and probably cannot yield useful DNA results,

but the defense says it has discredited the prosecution's

reports.

Almost all the blood at the murder scene was

Ms. Schnaps's, but a few spots on the box spring and on a

cardboard box under the bed looked like a mixture of her blood

and someone else's. Analyzing those samples for a blood enzyme

known as CAII, the laboratory found a type that appears in about

15 percent of the African-American population and never in

Caucasians. That was persuasive, apparently, to the first jury.

For the second trial, the prosecution

maintained that the DNA testing of the box spring and cardboard

box narrowed the universe of possible contributors to a tiny

percentage of the African-American population. Even the defense

expert testified that the blood would match at most 2 percent of

people of African ancestry.

But years later, Mr. Kleiner obtained lab

reports that the state had not released or that Mr. Harvey's

previous lawyers had overlooked. Then, his two blood experts

concluded that the earlier reports were erroneous, that the DNA

sample was probably contaminated, and that the blood tests from

Ms. Schnaps's apartment in 1985 had in fact eliminated Mr.

Harvey as a possible source.

The defense also learned of the items found

in the common laundry room - still unidentified and never tested.

So far, Mr. Kleiner has been unsuccessful in his request to have

them tested for blood.

As for the single "negroid hair," which

linked Mr. Harvey to the crime scene but was not conclusively

identified, Mr. Kleiner was told that all the hair evidence,

along with technicians' notes and microfilm, was missing. The

hair was gone before the first trial, it turned out - although

Mr. Kleiner says he suspects it never existed - and Mr. Harvey

had been convicted twice with evidence that no one ever produced

in court.

Meanwhile, there was another possible suspect,

Peter Stohwasser, to check out.

Mr. Harvey's first lawyer, Michael R. Justin,

did not seem to be aware of any earlier suspect. (What Mr.

Justin knew may never be clear; he committed suicide in 1989.)

At the second trial, Mr. Harvey's public defenders, Lorraine

Pullen and Al Glimis, named Mr. Stohwasser and suggested that he

had been cleared too soon. But they were stymied by an

investigator for the prosecutor's office, James T. O'Brien. Mr.

O'Brien's testimony contained two inaccuracies, unnoticed at the

time, that are now at the heart of Mr. Harvey's case.

The first came after Mr. O'Brien's cross-examination

by the defense, when the prosecutor, Robert H. Corbin, stepped

up to elicit a sharp response.

"Did Mr. Stohwasser to your knowledge ever

submit to a polygraph?" the prosecutor asked.

"Yes," Mr. O'Brien answered.

"Did he pass?"

"Yes, he did."

The jurors were told to disregard the

testimony, since polygraph evidence is not admissible in court,

but they were not told that Mr. Stohwasser in fact had failed

the polygraph. The defense lawyers did not know, either. After

Mr. Kleiner obtained the polygrapher's charts in June 2003, two

polygraph experts, Richard Arther and Catherine Arther, reported

they had "no doubt" that Mr. Stohwasser lied on all the

questions about the murder.

In a recent interview, Mr. Arther said that

the polygrapher - whom he had trained, as it happened - had done

an impressive job and that he was "appalled" that the

prosecutor's office did not pursue Mr. Stohwasser. Catherine

Arther, Mr. Arther's daughter, who works with him in teaching

polygraph techniques, added: "We don't know why they shifted

their attention over to Harvey. We feel strongly about this

case."

The testimony of Mr. O'Brien, who has retired

and could not be reached for comment, remains unexplained. Mr.

Corbin, now in private practice, said he could not remember the

testimony or the polygraph results, although he recalled that

some other allegations against Mr. Stohwasser "did not jibe."

Mr. Kapsak, the prosecutor who handled Mr.

Harvey's first trial, said: "Why O'Brien made that mistake I

don't know. I guess because they excluded him, they assumed that

he passed the test."

In the old records Mr. Kleiner says he also

found, in fragments, the story of Mr. Stohwasser's quilt.

The hairs from the quilt, initially

identified as Ms. Schnaps's, are missing. The bloodstained

swatches from the quilt are gone, too. Mr. O'Brien testified

that the quilt and Mr. Stohwasser's other belongings "came back

negative for blood."

But Mr. Kleiner's serologist concluded that

the testing did show blood and identified an enzyme carried by

no more than one-third of the population, including Ms. Schnaps.

The blood on the quilt, like the polygraph

results, never came to the attention of the Supreme Court. Yet

the inaccurate testimony went unchallenged, and on appeal the

state did not correct it, and it became the official version -

the Supreme Court's version - of the murder story.

Another Murder Victim

Mr. Kleiner also found out about a cold case

in East Windsor - a murder that occurred 16 months before Irene

Schnaps was killed. Nathaniel Harvey was a suspect at one point,

and Mr. Kleiner would decide that Peter Stohwasser should have

been a suspect, too.

The victim, Donna Macho, 19, was attacked in

the early morning of Feb. 26, 1984, in her apartment in the

basement of her mother's and stepfather's house. No one heard

screams and there was no sign of forced entry, but the room was

bloody. Her body was not discovered until 1995, in a field less

than a mile from Hunter's Glen.

Mr. Kleiner and his investigator uncovered

what he said was a stunning coincidence: Ms. Macho and Mr.

Stohwasser both took evening classes at Mercer County Community

College in the fall of 1983, according to college records that

Mr. Kleiner filed with the court. After Ms. Macho's

disappearance, Mr. Stohwasser did not report for spring classes

he had signed up for.

Mr. Kleiner also found a psychic, John Monti,

who had been hired by the East Windsor police and interviewed

Donna's mother before she died in 1990. In Mr. Monti's notes,

which are also in court files, was her disjointed recollection

of a man in his 30's: "Peter Stow? Show?" The notes continued: "Peter

- college - crazy over Donna, jealous over her. If I don't get

her, nobody will, mother said."

Mr. Stohwasser says he never met Ms. Macho

and he never heard of the case until a reporter asked him about

it recently.

Ms. Macho's sister, Jeana Macho Savage, who

lives in Texas, says she has no knowledge of Mr. Stohwasser but

believes Donna's killer knew her, and knew of the basement

apartment. An intruder "wouldn't normally go down there looking

unless you knew there was somebody there," Mrs. Savage said in a

recent interview.

East Windsor Police Chief William Spain would

not comment except to say the Macho case was "an active,

continuing investigation." But Mrs. Savage said the police did

not even interview any family members when her sister's body was

found. "I don't feel that they've done my sister any justice

whatsoever," she said.

*****

When Judge John F. Malone of Superior Court

in Elizabeth ruled against Mr. Harvey last month, he said a

habeas petition "is not a device for investigating possible

claims nor an opportunity to second-guess trial counsel's

tactical decisions." The prosecutors said they were confident

that the Supreme Court would uphold Judge Malone.

"This case never was, and never will be, one

about innocence," Assistant Prosecutor Nancy Hulett, who has

represented the state on Mr. Harvey's appeals, said in an e-mail

message after Judge Malone's decision.

In a brief interview, Ms. Hulett returned to

the confession and the DNA evidence. "This is a case where the

defendant confessed," she said. "He's been convicted twice. He

was convicted on two bodies of evidence."

New Jersey has not executed anyone since

1963, and Mr. Harvey, if turned down by the State Supreme Court,

can bring a habeas case in federal court. Mr. Kleiner is still

looking for more evidence.

"It would be nice if we knew we were right,"

he said, "before we execute someone."