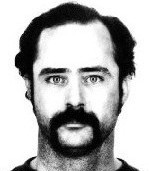

STEVENS,

J., Concurring Opinion

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

465 U.S. 37

Pulley v. Harris

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH

CIRCUIT

No. 82-1095

Argued: November 7, 1983

--- Decided: January 23,

1984

JUSTICE STEVENS, concurring

in part and concurring in the judgment.

While I

agree with the basic conclusion of Part III

of the Court's opinion -- our case law does

not establish a constitutional requirement

that comparative proportionality review be

conducted by an appellate court in every

case in which the death penalty is imposed

-- my understanding of our decisions in

Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153

(1976); Proffitt v. Florida, 428

U.S. 242 (1976); Jurek v. Texas,

428 U.S. 262 (1976); and Zant v.

Stephens, 462 U.S. 862 (1983), is

sufficiently different from that reflected

in Part III to prevent me from joining that

portion of the opinion.

While

the cases relied upon by respondent do not

establish that comparative proportionality

review is a constitutionally required

element of a capital sentencing system, I

believe the case law does establish that

appellate review plays an essential role in

eliminating the systemic arbitrariness and

capriciousness which infected death penalty

schemes invalidated by Furman v. Georgia,

408 U.S. 238 (1972), and hence that

some form of meaningful appellate review is

constitutionally required.

[p55]

The

systemic arbitrariness and capriciousness in

the imposition of capital punishment under

statutory schemes invalidated by Furman

resulted from two basic defects in those

schemes. First, the systems were permitting

the imposition of capital punishment in

broad classes of offenses for which the

penalty would always constitute cruel and

unusual punishment. Second, even among those

types of homicides for which the death

penalty could be constitutionally imposed as

punishment, the schemes vested essentially

unfettered discretion in juries and trial

judges to impose the death sentence. Given

these defects, arbitrariness and

capriciousness in the imposition of the

punishment were inevitable, and, given the

extreme nature of the punishment,

constitutionally intolerable. The statutes

we have approved in Gregg, Proffitt,

and Jurek were designed to eliminate

each of these defects. Each scheme provided

an effective mechanism for categorically

narrowing the class of offenses for which

the death penalty could be imposed, and

provided special procedural safeguards

including appellate review of the sentencing

authority's decision to impose the death

penalty.

In

Gregg, the opinion of Justices Stewart,

POWELL, and STEVENS indicated that some form

of meaningful appellate review is required,

see 428 U.S. at 198, and that opinion,

id. at 204-206, as well as JUSTICE

WHITE's opinion, see id. at 224,

focused on the proportionality review

component of the Georgia statute because it

was a prominent, innovative, and noteworthy

feature that had been specifically designed

to combat effectively the systemic problems

in capital sentencing which had invalidated

the prior Georgia capital sentencing scheme.

But observations that this innovation is an

effective safeguard do not mean that it is

the only method of ensuring that death

sentences are not imposed capriciously, or

that it is the only acceptable form of

appellate review.

In

Proffitt, the joint opinion of Justices

Stewart, POWELL, and STEVENS explicitly

recognized that the Florida "law differs

from that of Georgia in that it does not

require the court to conduct any specific

form of review." 428 U.S. at

[p56] 250-251. The opinion

observed, however, that "meaningful

appellate review" was made possible by the

requirement that the trial judge justify the

imposition of a death sentence with written

findings, and further observed that the

Supreme Court of Florida had indicated that

death sentences would be reviewed to ensure

that they are consistent with the sentences

imposed in similar cases. Id. at 251.

Under the Florida practice as described in

the Proffitt opinion, the appellate

review routinely involved an independent

analysis of the aggravating and mitigating

circumstances in the particular case. Id.

at 253. Later in the opinion, in response to

Proffitt's argument that the Florida

appellate review process was "subjective and

unpredictable," id. at 258, we noted

that the State Supreme Court had "several

times" compared the circumstances of a case

under review with those of previous cases in

which the death sentence had been imposed

and that by "following this procedure the

Florida court has in effect adopted the type

of proportionality review mandated by the

Georgia statute." Id. at 259. We did

not, however, indicate that the particular

procedure that had been followed "several

times" was either the invariable routine in

Florida,

[*] or that it was an

indispensable feature of meaningful

appellate review. [p57]

The

Texas statute reviewed in Jurek, like

the Florida statute reviewed in Proffitt,

did not provide for comparative review. We

nevertheless concluded "that Texas' capital

[p58] sentencing

procedures, like those of Georgia and

Florida," were constitutional because they

assured that "sentences of death will not be

‘wantonly' or ‘freakishly' imposed." 428

U.S. at 276. That assurance rested in part

on the statutory guarantee of meaningful

appellate review. As we stated:

By

providing prompt judicial review of the

jury's decision in a court with

statewide jurisdiction, Texas has

provided a means to promote the

evenhanded, rational, and consistent

imposition of death sentences under law.

Ibid.

Thus, in all three cases decided on the same

day, we relied in part on the guarantee of

meaningful appellate review, and we found no

reason to differentiate among the three

statutes in appraising the quality of the

review that was mandated.

Last

Term, in Zant v. Stephens, 462

U.S. 862 (1983), we again reviewed the

Georgia sentencing scheme. The Court

observed that the appellate review of every

death penalty proceeding "to determine

whether the sentence was arbitrary or

disproportionate" was one of the two primary

features upon which the Gregg joint

opinion's approval of the Georgia scheme

rested. 462 U.S. at 876. While the Court did

not focus on the comparative review element

of the scheme in reaffirming the

constitutionality of the Georgia statute,

appellate review of the sentencing decision

was deemed essential to upholding its

constitutionality. Id. at 876-877,

and n. 15. The fact that the Georgia Supreme

Court had reviewed the sentence in question

"to determine whether it was arbitrary,

excessive, or disproportionate"

[p59] was relied

upon to reject a contention that the statute

was invalid as applied because of the

absence of standards to guide the jury in

weighing the significance of aggravating

circumstances, id. at 879-880 (footnote

describing proportionality review omitted),

and the mandatory appellate review was also

relied upon in rejecting the argument that

the subsequent invalidation of one of the

aggravating circumstances found by the jury

required setting aside the death sentence,

id. at 890. Once again,

proportionality review was viewed as an

effective, additional safeguard against

arbitrary and capricious death sentences.

While we did not hold that comparative

proportionality review is a mandated

component of a constitutionally acceptable

capital sentencing system, our decision

certainly recognized what was plain from

Gregg, Proffitt, and Jurek: that

some form of meaningful appellate review is

an essential safeguard against the arbitrary

and capricious imposition of death sentences

by individual juries and judges.

To

summarize, in each of the statutory schemes

approved in our prior cases, as in the

scheme we review today, meaningful appellate

review is an indispensable component of the

Court's determination that the State's

capital sentencing procedure is valid. Like

the Court, however, I am not persuaded that

the particular form of review prescribed by

statute in Georgia -- comparative

proportionality review -- is the only method

by which an appellate court can avoid the

danger that the imposition of the death

sentence in a particular case, or a

particular class of cases, will be so

extraordinary as to violate the Eighth

Amendment.

Accordingly, I join in all but Part III of

the Court's opinion, and concur in the

judgment.

The Florida Supreme Court

now undertakes to provide proportionality

review in every case, see Brown v.

Wainwright, 392 So.2d 1327, 1331,

cert. denied, 454 U.S. 1000

(1981). As we noted in Proffitt, this

practice does provide the "function of death

sentence review with a maximum of

rationality and consistency." 428 U.S. at

258-259. The fact that the practice is an

especially good one, however, does not mean

that it is an indispensable element of

meaningful appellate review.