Opinion Author: William Ray Price, Jr., Judge

Opinion Vote: AFFIRMED. All concur.

Opinion:

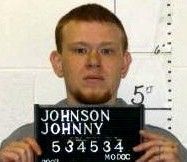

A jury convicted Johnny Johnson of first-degree

murder and recommended a sentence of death. The jury also convicted him

of armed criminal action, kidnapping, and attempted forcible rape and

recommended life sentences for these crimes. Judgment was entered

consistent with the jury recommendations. Because Johnson was sentenced

to death, this Court has exclusive jurisdiction of his appeal. Mo.

Const. art. V, sec. 3. The judgment is affirmed.

I. Facts

Johnny Johnson's convictions resulted from the murder

of six-year old Casey Williamson on July 26, 2002. Casey lived with her

mother, Angie, and her siblings at her grandfather's home on Benton

Street in Valley Park. Casey's parents were separated and her father,

Ernie, lived across the street, in the home of Michelle Rehm and her

boyfriend Eddy, so that he could remain close to his children.

Two days before Casey's murder, on July 24, 2002,

Johnson went to Michelle's house to look for Eddy and Ernie. That same

day, he was seen by Casey's sister, Chelsea, and her friend, Angel, when

they were riding bikes on Benton Street. Chelsea and her friend noticed

that Johnson was following them and sped up as they returned home.

On the night of July 24, 2002, Angie took the

children to Michelle's house to spend the night with Ernie. Johnson also

stayed at Michelle's house that evening.

The next morning, July 25, 2002, Angie awoke to find

Casey on the couch watching cartoons with Johnson. Johnson told Angie

that Casey was not bothering him. Unbeknownst to anyone at the time,

however, Johnson had begun to think Casey was "cute" and had "ideas" of

wanting to have sex with her.

That day, Angie took the children back to her

father's house for the day. At one point during the day, Casey, her

sister, and other friends, including Angel, were at the home by

themselves. Angel noticed Johnson sitting on a chair by the deck and

locked the door. Angel later heard knocking, but did not answer the door.

On the evening of July 25, 2002, Johnson joined in a

barbeque at Michelle's house. That evening, Casey and her siblings again

spent the night with their father at Michelle's house.

The next morning, July 26, 2002, Ernie awoke around

6:00 a.m. to prepare for work. Casey awoke and said she was hungry.

Ernie told her that he would take her to her grandfather's house to get

breakfast and told her to wait upstairs while he went downstairs to get

ready for work. Downstairs, he noticed Johnson asleep on the couch.

Casey did not stay upstairs. Johnson awoke to find

Casey standing near the couch watching television and sensed this was

his best opportunity to have sex with her. He had decided that to avoid

being caught for sexually assaulting her, he would kill her after having

sex with her. Johnson asked Casey if she wanted to go to the glass

factory to play games and have fun. Casey said she would go with him and

they left. Casey was wearing only her nightgown and underwear. As they

walked down Benton Street and into an alley, Casey complained her feet

hurt and Johnson picked her up and carried her. When they came to the

woods leading to the glass factory, they walked along one of the paths

to a sunken pit with brick and concrete walls more than 6 feet high.

Casey and Johnson crawled through a small tunnel and dropped into the

pit.

Johnson asked Casey if she wanted to see his penis.

She said no, but he pulled down his shorts and exposed himself. Casey

turned her head away. Johnson then asked Casey to pull down her panties

so he could see her vagina. She said no, and Johnson grabbed her

underwear, tore it off her, and forced her to the ground. Pinning her to

the ground with his chest, Johnson attempted to achieve an erection by

rubbing his penis on Casey's leg. Casey started screaming, kicking, and

pushing at Johnson, scratching his chest.

Even though he had not yet raped Casey, Johnson got

up and decided to kill her. He grabbed a brick and hit Casey in the head

with it at least six times, causing bleeding and bruising. She was not

yet dead or knocked unconscious and started to run around the pit.

Johnson hit her with the brick again. She fell to her knees and tried to

crawl away from Johnson. He struck her with the brick again, eventually

knocking her to the ground and fracturing the right side of her skull.

Because she was still moving, Johnson then lifted a basketball-sized

boulder and brought it down on the back left side of Casey's head and

neck, causing multiple skull fractures. Casey inhaled and exhaled

"really fast" and then stopped breathing.

Johnson wiped blood from Casey's face with her

underpants and then threw them in an opening in the wall. He buried

Casey with rocks, leaves, and debris from the pit. He then went to the

nearby Meramec River to wash Casey's blood and other evidence from his

body.

The police were looking for Johnson. Officer Chad

Lewis met up with him. He had Johnson get in a police car to talk

because there were so many people in the area. Without any question

being asked, Johnson said he would not hurt "little kids" and that he

liked them because he had one of his own. He explained to Officer Louis

that he had gone for a swim in the river and explained his route there.

Officer Louis thought Johnson's route was unusual because most locals

would have cut through the glass factory to get to the river. He asked

Johnson if he had been in the glass factory, which Johnson denied. At

Officer Louis's request, Johnson agreed to go to the police station to

talk in private.

While at the station, Johnson was identified by a

witness who had seen him carrying Casey that morning. Around 8:30 a.m.,

Detectives Neske and Knieb arrived at the station and took Johnson to a

police substation that had an open interview room. On the ride to the

substation, Johnson was informed of his rights and indicated he

understood them. At the substation, around 9:25 a.m., Johnson signed a

waiver form after again being advised of his rights. Johnson said he

wanted to make a statement. For about an hour, Johnson and Detective

Neske conversed, and Johnson denied seeing or being with Casey that

morning. Even when confronted with accounts of witnesses seeing him with

Casey that morning, Johnson continued his denials.

When Detective Neske brought up a hypothetical about

Johnson's son being missing, Johnson became angry. Johnson said he was

being treated for schizophrenia and had been hospitalized for it in the

past. Johnson denied that he was hearing voices and said he usually only

saw shadows, but he denied having any hallucinations at that time.

Johnson said he had not taken any medication for a month and was not

suffering from it anymore.

The detectives took a break from talking with Johnson

and brought him food. In the early afternoon, about 1:30 p.m., Johnson

agreed to submit to a rape kit. Before the samples were collected,

Detective Neske told Johnson that they would determine his involvement

and said he needed "to be a man and tell me where she's at." Johnson

started crying and said, "She's in the old glass factory."

When asked if Casey was alive, Johnson said she was

dead and it was an accident. He said that Casey wanted to go to the

glass factory with him and that a rock had fallen from the pit wall when

he was climbing it and hit Casey's head, killing her. Johnson said he

then "freaked out," thinking he would not be believed, and buried Casey.

He said he went to the river to kill himself, but could not. Johnson

drew two maps to help officers find Casey's body, but officers at the

scene were unable to find the body and Johnson was taken there.

Before Johnson arrived, however, a private citizen

who had joined the search for Casey that morning came upon the tunnel

leading to the pit where Johnson had taken Casey. In the middle of the

pit, he saw a pile of rocks, blood around the pile, and Casey's foot

between the rocks. He saw "a piece of concrete that probably weighed a

hundred pounds" where Casey's head would have been. Police arrived and

secured the pit.

Johnson was taken to police headquarters. Detective

Neske observed the pit and spoke with an officer who was processing

evidence at the scene. The evidence officer told Detective Neske that

there was no place to climb out of the pit and said there was blood all

over the floor of the pit, which contradicted Johnson's story.

Detective Neske went to police headquarters to talk

with Johnson. He again advised Johnson of his rights and the waivers,

and said he had been to the scene and did not think it was an accident.

Johnson then told Detective Neske that once he and Casey were in the pit

he had asked Casey if she wanted to see his penis and pulled down his

pants. Johnson said that he asked Casey to show him her vagina and

pulled off her underwear, which caused her to start "freaking out" and

saying she would tell her parents. Johnson said this caused him to start

"freaking out" as well, and he picked up the brick and hit her a couple

of times in the head, then dropped the "boulder" on her head. He said he

wanted her to expose herself so he could masturbate. He said he wiped

blood from Casey's face with the underwear, discarded it, buried the

body, and went to the river to wash off the blood. Around 8:30 p.m.,

Johnson repeated this version of events in an audiotaped statement. In

these statements, Johnson did not admit that he intended to take Casey,

rape her, or kill her prior to entering the pit.

Later that night, around 11:30 p.m., Detective John

Newsham was instructed to take Johnson to the county jail. While Johnson

was awaiting booking, Detective Newsham began discussing reading with

him. Johnson said he liked to read the Bible and was concerned about his

"eternal salvation." He said he was "fine," and that he "felt he was

going to receive the death penalty and that he wanted to be executed."

He asked Detective Newsham, "[D]o you think I'll ever achieve eternal

salvation[?]" Detective Newsham thought that Johnson was indicating he

had not been completely honest earlier and he took this as an

opportunity to get more information. He told Johnson that to be forgiven

for this crime he had to be completely truthful and honest and not leave

out details. Johnson admitted he had not been completely honest. Johnson

was returned to police headquarters, again waived his rights, and made

verbal and audiotaped statements. In these statements, he admitted that

he intended to take Casey for the purpose of having sex with her and

planned to kill her after doing so.

An autopsy showed that Casey died from blunt force

injuries to her head, which caused skull fractures and bruising of her

scalp and brain. She also suffered injuries to her arms, shoulders, legs,

and back. Her blood was found on Johnson's shirt and a brick and large

rock recovered from the pit. Johnson's semen was found on his shorts.

At trial, Johnson did not deny killing Casey, but

disputed that he deliberated before doing so. His diminished capacity

defense asserted that he could not deliberate due to mental illness,

specifically schizo-affective disorder that caused command

hallucinations to rape and kill Casey. In rebuttal, the State's expert

testified that Johnson was capable of deliberation and any

hallucinations that he may have had at the time were due to

methamphetamine intoxication, not psychosis.

The jury found Johnson guilty of all offenses. In the

penalty phase, the jury recommended a sentence of death for murder,

finding all three statutory aggravators submitted. Johnson was sentenced

to death for murder and as a persistent offender to consecutive life

sentences for the other charged crimes.

II. Standards of Review

The evidence is reviewed in the light most favorable

to the verdict. State v. Strong, 142 S.W.3d 702, 710 (Mo. banc

2004). This Court's direct appeal review is for prejudice, not mere

error, and the trial court's decision will be reversed only if the error

was so prejudicial that it deprived the defendant of a fair trial. Id.

Trial court error is not prejudicial unless there is a reasonable

probability that the trial court's error affected the outcome of the

trial. State v. Zink, 181 S.W.3d 66, 73 (Mo. banc 2005). Any

issue that was not preserved can only be reviewed for plain error, which

requires a finding that manifest injustice or miscarriage of justice has

resulted from the trial court error. State v. Glass, 136 S.W.3d

496, 507 (Mo. banc 2004).

III. Issues on Appeal

Johnson raises 10 points of error: (1) the trial

court erred in overruling his Batson challenges to the State's

peremptory strikes of an African-American male juror and an Asian female

juror; (2) the trial court erred in precluding defense counsel from

asking prospective jurors whether, knowing that first-degree murder is a

coolly-reflected-upon, deliberated killing, they could consider a

sentence of life imprisonment without probation or parole; (3) the trial

court erred in allowing the state to elicit evidence of uncharged crimes

of "stalking" children in the days preceding Casey's murder over his

objections; (4) the trial court erred in submitting a voluntary

intoxication instruction, Instruction 6, over his objections; (5) the

trial court erred in overruling his motion to suppress statements he

made to Detective Newsham; (6) the trial court erred in overruling his

objections and submitting Instruction 23, the statutory aggravator that

the murder "was outrageously or wantonly vile"; (7) the trial court

erred in overruling his new trial motion and sentencing him to death;

(8) the trial court erred in overruling his objections to Instructions

24 and 26 because they did not properly instruct the jury about how to

weigh the mitigating and aggravating factors presented; (9) the trial

court erred in overruling his motion to quash the information or,

alternatively, preclude the death penalty and death sentence; and (10)

the trial court plainly erred in failing to admonish the prosecutor and

give a corrective instruction when he stated in guilt phase closing

argument that the jury should "for once" hold Johnson responsible.

A. Batson Challenges

Johnson alleges that the trial court erred in

overruling his Batson challenges to the State's peremptory

strikes of an African-American male juror, Murphy, and an Asian female

juror, Gilbert. In addition to arguing that the State's race-neutral

reasons for striking Murphy and Gilbert were pretextual, Johnson also

asserts that the court wrongly denied him the opportunity to show

pretext.

1. Batson Standards

Parties cannot exercise peremptory challenges to

remove potential jurors solely based on the jurors' gender, ethnicity,

or race. Strong, 142 S.W.3d at 712. In raising a race-based

Batson challenge, three steps are followed: (1) the defendant raises

a Batson challenge with respect to a specific venireperson struck

by the State, identifying the cognizable racial group to which that

person belongs; (2) the State must supply a reasonably specific and

clear race-neutral reason for the challenged strike; and (3) if the

state provides an acceptable reason for the strike, then the defendant

must show that the State's given reason or reasons were merely

pretextual and that the strike was racially motivated. Id.

In determining pretext, the main consideration is the

plausibility of the prosecutor's explanations in light of the totality

of the facts and circumstances surrounding the case. State v. Edwards,

116 S.W.3d 511, 527 (Mo. banc 2003). The court also considers the

presence of similarly situated white jurors who were not struck.

Strong, 142 S.W.3d at 712. "Evidence of purposeful discrimination is

established when the stated reason for striking [a minority]

venireperson applies to an otherwise-similar member of another race who

is permitted to serve." State v. McFadden, 191 S.W.3d 648, 651 (Mo.

banc 2006). Other factors the court considers include the logical

relevance between the State's proffered explanation and the case to be

tried, the prosecutor's credibility based on his or her demeanor or

statements during voir dire and the court's past experiences with the

prosecutor, and the demeanor of the excluded venireperson. Strong,

142 S.W.3d at 712. Finally, the court can consider objective factors

bearing on the State's motive to discriminate on the basis of race, such

as conditions prevailing in the community and the race of the defendant,

the victim, and the material witnesses. Edwards, 116 S.W.3d at

527.

This Court defers to the trial court in these matters,

and will overturn its decision only upon a showing of clear error.

State v. Morrow, 968 S.W.2d 100, 113 (Mo. banc 1998). A clear error

is one that leaves this Court with a definite and firm conviction that a

mistake has been committed. Id.

2. Challenged Strikes

Johnson maintains that the State's strikes of

venirepersons Murphy and Gilbert were pretextual. He also complains that

the trial court erred in denying his Batson challenges before

giving him a chance to demonstrate pretext.

The following exchange took place after the

prosecutor's peremptory strikes:

[Defense Counsel]: We'll make a Batson motion

as to two jurors. The first one is . . . [Murphy], who is an African-American

male. We would ask the State to state their reason for that strike.

. . . .

[Prosecutor]: Regarding [Murphy] . . . he is single, not married, with

no children. As we know this case involves the death of a very young

child and so I looked for jurors, among other things, who have children.

He's also a youth specialist so he has some contact with kids working

for the Division of Young Services for a number of years, if not an

actual social worker or towards social work, works with troubled kids.

My concern, he might see himself in the position to save the defendant

or could identify with one of the kids he works with and treats for the

past three years.

[Court]: I think that's a viable reason to deny the

Batson challenge.

[Defense Counsel]: The other one is to both gender

and race as to . . . Gilbert, who appears to be an Asian female.

. . . .

[Prosecutor]: Also Mrs. Gilbert, though a married woman, indicates she

has no minor children. She is a student, she lists her occupation as a

student, and I'm trying to figure out how to be polite, she doesn't look

to be the typical student age range, which leads me to believe she may

be a professional student. Students tend not to have the sort of life

experiences I think would be important life experiences you would have

with kids and life experiences being something other than a student.

[Court]: All right. I'll overrule the Batson

challenge.

[Defense Counsel]: If you could make a record, the

State indicated the State struck the juror because she didn't have

children? Did you say that was the reason for Gilbert?

[Prosecutor]: Yeah, one of the reasons. There's no

single reason for anybody, but that's mainly one of the considerations

in both selecting and striking jurors with minor children.

[Defense Counsel]: Juror . . . Travers, white male,

also has no children. The State did not use any peremptory challenges

for him. Also, juror . . . Maloney, whi[t]e male, who has no children,

the State did not exercise any challenges for him.

[Prosecutor]: Both Travers and Maloney, the reasons I

struck the others, it's not just for people with children, that's not

the sole consideration. They also had responses, at least by mannerism,

certainly would appear to be favoring the State's position.

[Defense Counsel]: I'm pointing out those jurors that

are similarly situated, they don't have children. I think that's part of

the record we need to make.

[Prosecutor]: They are not just students, they don't

work for the Division of Youth Services. While they didn't have children,

they also don't have some of the other matters that I thought were

important in consideration of striking the others."

The discussion of the strikes of Murphy and Gilbert

then ended without any further comment from the trial court.

3. Pretext

Johnson fails to show that the State's reasons for

striking venirepersons Murphy and Gilbert were pretextual and that the

strikes were racially motivated. The State used each of its peremptory

strikes to strike venirepersons without minor children, including white

venirepersons who did not have children. "[I]t is well-recognized that

an important factor in determining whether the defendant has proved

purposeful discrimination is whether the State used peremptory

challenges to remove similarly situated Caucasian venirepersons."

State v. Ashley, 940 S.W.2d 927, 932 (Mo. App. 1997). Johnson cannot

demonstrate pretext in the prosecutor's claim that one of his reasons

for striking Murphy and Gilbert was their lack of minor children given

that the State's challenges were exhausted removing minorless

venirepersons, while minority venirepersons remained on the jury panel.

See State v. Shurn, 866 S.W.3d 447, 456 (Mo. banc 1993) ("[T]he

prosecutor's failure to use all his challenges against blacks is

relevant to show that race was not the motive for the use of peremptory

strikes.").

Given the facts of the case, it was logical for the

State to want jurors who had minor children. Johnson's counsel

recognized the prosecutor's logic in striking minorless venirepersons

when she explained that she had struck a female venireperson for reasons

that included: "She has children. Just as the State indicated they were

interested in finding jurors with children, we believe jurors with

children might be a detriment to us because of the nature of the charge."

Johnson also fails to show there was pretext in the

State's reasons for striking Murphy and Gilbert based on their

occupations. "Employment is a valid race-neutral basis for striking a

prospective juror." State v. Williams, 97 S.W.3d 462, 472 (Mo.

banc 2003). It was logical for the prosecutor to believe that Murphy's

work with the Division of Youth Services might make him more sympathetic

to Johnson. Similarly, the prosecutor was concerned that Gilbert's

occupation as a student caused her to lack sufficient life experiences

he would prefer in jurors. The prosecutor's preference for jurors with

life experience was demonstrated by his use of peremptory strikes

against venirepersons Schafer and Johnson, who had worked at their jobs

less than a year, and venireperson Milan, who was unemployed. Each of

the jurors who served on the jury was employed for five or more years.

Johnson argues that the prosecutor's failure to ask

questions during voir dire relating to his reasons for striking Murphy

and Gilbert undermines the plausibility of his explanations. He asserts

that if the issues of children or occupations truly mattered, the

prosecutor would have inquired about those subjects on voir dire, rather

than relying on juror questionnaire responses. In support of this

proposition, Johnson cites Miller-El v. Dretke, wherein the

United States Supreme Court found pretext where a prosecutor's purported

reasons for striking a prospective juror were "makeweight" and "reek[ed]

of afterthought" and the prosecutor had not inquired into the subject

during voir dire, suggesting it did not "actually [matter]." 125 S.Ct.

2317, 2328 (2005) (citing Ex parte Travis, 776 So.2d 874, 881

(Ala. 2000) ("[T]he State's failure to engage in any meaningful voir

dire examination on a subject the State alleges it is concerned about is

evidence suggesting that the explanation is a sham and a pretext for

discrimination")). Unlike in Miller-El, however, the prosecutor's

reasoning in this case was not "makeweight" or "reeking of afterthought."

Johnson criticizes the prosecutor's failure to ask

Murphy and Gilbert voir dire questions that would have illuminated their

past experiences with children, but he does not allege that the

prosecutor made similar inquiries to other venirepersons listed as

without children on the questionnaires. The prosecutor's reliance on the

questionnaire information was warranted because sufficient information

was available from the questionnaires to support his reasoning for

striking Murphy, Gilbert, and the other venirepersons without children

who were struck.

4. Batson Procedure

Johnson further argues that the trial court erred in

deciding his Batson challenges because it denied him an

opportunity to carry his burden of showing purposeful discrimination.

The trial court denied the Batson challenges as to Murphy and

Gilbert immediately after the prosecutor explained his reasons for the

strikes. Johnson contends that, in doing so, the trial court failed to

consider Batson's third stage--whether or not the prosecutor's

reasoning was pretextual.

Johnson's argument relies on State v. Phillips,

941 S.W.2d 599, 604 (Mo. App. 1997), wherein the Eastern District opined

that denying a defendant a chance to show purposeful discrimination

before denying a Batson challenge constituted trial court error.

The Phillips court rejected the State's argument that giving the

defendant an opportunity to make a record after the court's ruling was

sufficient. 941 S.W.2d at 604. Phillips, however, offers limited

guidance in this case because its discussion of the trial court's

premature ruling on the defendant's Batson challenge followed the

reversal of the defendant's conviction on another ground and the court

did not explore the impact of the trial court's error in ruling on the

Batson challenge. In short, the language relied on by Johnson is

dicta.

Johnson argues that the trial court's premature

rulings on his Batson challenges constituted structural error

requiring reversal and remand because it involves jury selection. "Structural

defects" are constitutional errors that "defy analysis by 'harmless-error'

standards" because they "affec[t] the framework within which the trial

proceeds, [and are not] simply [errors] in the trial process itself."

Arizona v. Fulminante, 499 U.S. 279, 309-10 (1991).

The State, however, maintains that any error in

ruling prematurely was merely a procedural error, not a structural

error, and should be reviewed for prejudice. It argues that Johnson was

not prejudiced because each step required under Batson was

fulfilled insofar as Johnson was given an opportunity to make arguments

as to pretext after the trial court's initial denial and, as such, the

trial court considered the issue of pretext.

Johnson complains that the trial court too quickly

ruled on his Batson challenges, but he does not argue that the

trial court applied an improper standard in deciding the issue or that

it prevented him from exercising his peremptory challenges.

The trial court's premature ruling did not prevent it

from considering Johnson's arguments as to pretext. After the trial

court denied the Batson challenge as to Murphy, defense counsel

immediately raised her challenge as to Gilbert, without complaining that

she was not allowed to demonstrate prextext before the court's ruling.

After the Gilbert challenge was also denied, defense counsel then

immediately began an inquiry suggesting why the prosecutor's reasons for

striking Murphy and Gilbert were pretextual.

The primary consideration in examining a procedural

Batson challenge is whether the defendant had a full and fair

opportunity to set out his or her arguments and to make a complete

record for review. While the three-step process required by Batson

was not followed in order, no step of the process was omitted. Because

Johnson was afforded consideration of each step of the Batson

process, he was not prejudiced by the trial court's failure to follow

the steps in a precise order. Neither was he denied the opportunity to

make a record of his evidence or arguments. Under these circumstances,

the court's premature ruling resembles an error of process, not a

structural defect that impacted the framework of Johnson's trial.

Because Johnson cannot show that he was prejudiced by the trial court's

premature Batson ruling, he is not entitled to relief on this

issue.

The trial court did not err in overruling Johnson's

Batson challenges and permitting the prosecutor's peremptory

strikes of Murphy and Gilbert.

B. Restriction of Voir Dire Questioning

Johnson argues that the trial court erred by not

allowing defense counsel's questions during voir dire that asked

venirepersons whether, knowing that first-degree murder is a coolly-reflected-upon,

deliberated killing, they could consider a sentence of life imprisonment

without probation or parole. He asserts that the trial court's ruling

prevented defense counsel from knowing venirepersons' views on the issue

of punishment for first-degree murder, thereby hindering determination

of who would be a suitable juror and denying him effective assistance of

counsel.

1. Standards for Review

A defendant is entitled to a fair and impartial jury.

U.S. Const. amends. VI, XIV; Mo. Const. art. I, sec. 18(a). A necessary

component of the guarantee for an impartial jury is an adequate voir

dire that identifies unqualified jurors. Morgan v. Illinois,

504 U.S. 719, 729-30 (1992) (adequate voir dire needed for trial judge

to fulfill responsibility to remove prospective jurors who are unable to

impartially follow the court's instructions and evaluate the evidence).

The trial judge is given wide discretion in conducting voir dire and

determining the appropriateness of specific voir dire questions.

State v. Oates, 12 S.W.3d 307, 310 (Mo. banc 2000).

The trial court's voir dire ruling will be reversed

only where an abuse of discretion is found and the defendant can

demonstrate prejudice. Id. at 311. A trial court abuses its

discretion when its ruling is clearly against the logic of the

circumstances and is so arbitrary and unreasonable as to shock the sense

of justice and indicate a lack of careful consideration. State v.

Brown, 939 S.W.2d 882, 883 (Mo. banc 1997). Where reasonable persons

can differ about the propriety of the action taken by the trial court,

no abuse of discretion will be found. Id. at 883-84. The

defendant bears the burden of showing that there is a "real probability"

that he was prejudiced by the abuse of discretion. Oates, 12 S.W.3d

at 310.

2. Voir Dire Restrictions

Johnson complains that his counsel was not allowed to

explain to venirepersons that imposition of the death penalty, as

opposed to a life sentence, would require that they find him guilty of

first-degree murder. During voir dire, defense counsel discussed that

first-degree murder would not include self-defense, an accident, or

catching a cheating spouse with a lover. The prosecutor objected,

arguing that defense counsel was inappropriately attempting to define

the crime of first-degree murder. He argued that it was the court's

responsibility to instruct the jury and the verdict director would

provide jurors with the definition of deliberation and the elements of

first-degree murder. Defense counsel explained that her questions were

designed to elicit information about whether venirepersons who say they

can consider a life sentence mean that they can consider a life sentence

for a deliberate killing, not just an accidental killing or for self-defense.

The trial court found that defense counsel's

questions did not give venirepersons a "full and complete definition of

murder first degree." It found that the questions "invade[d] the

province of the court" and were an "improper attempt to instruct the

jury on what the law is." The trial court suggested that defense counsel

ask, "Can you give life without probation and parole if you find him

guilty of first degree murder[?]," rather than attempt to define first

degree murder.

3. Permissible Voir Dire Questions

In State v. Morrow, this Court rejected a

defendant's argument that the trial court erred in prohibiting voir dire

questions regarding the difference between first and second degree

murder because such restrictions prohibited him from intelligently

exercising his peremptory and for cause strikes. 968 S.W.2d at 111. This

Court found that the trial court did not abuse its discretion in

preventing the questions because counsel is not allowed to inform

venirepersons as to what law will be applied in the case or what

instructions will be given. Id. As in this case, the trial court

in Morrow aided defense counsel in developing an appropriate

alternative to the prohibited line of questioning. Id.

In State v. Hall, the defendant alleged that

the trial court erred in preventing his counsel's questions asking

venirepersons if they could recommend a sentence of life imprisonment

for a defendant who had "deliberated" and "coolly reflected" before

committing a murder. 955 S.W.2d 198, 203 (Mo. banc 1997). This Court

found the trial court properly sustained the State's objections to the

questions because it is the role of the court to instruct jurors as to

the legal definitions regarding intent. Id. Hall states

that "[v]oir dire is not the proper arena for the legal definitions that

appear in jury instructions as the venirepanel is not the jury, nor does

it have evidence before it." Id. The trial court in Hall

advised defense counsel to limit questioning to whether the

venirepersons could consider the full range of punishment for

first-degree murder authorized by law. Id.

Johnson cites State v. Gray, 887 S.W.2d 369,

379 (Mo. banc 1994), for the proposition that "[i]n order to discover

bias of potential jurors, it is often necessary to reveal some factual

or legal detail in voir dire." While it is true that the "trial court

may permit parties to inquire whether potential jurors have

preconceived notions on the law which will impede their ability to

follow instructions on issues which will arise in the case," such

decisions are properly left to the discretion of the trial court.

State v. Ramsey, 864 S.W.2d 320, 335-36 (Mo. banc 1993) (emphasis

added). In Gray, the trial judge used hypothetical discussions to

explain accessory liability and reasonable doubt to venirepersons. 887

S.W.2d at 378-79. While no plain error was found in the judge's

comments, this Court cautioned that "[d]espite his well-intended

purposes, the judge said far more than was necessary in this case" and

that it would have been best for the remarks to "[avoid] the appearance

of giving an instruction of law or commenting on the evidence." Id.

at 379. This Court noted that the "purpose of the Approved Jury

Instructions is to avoid confusion among jurors [and] [t]hat purpose is

undermined when a judge or lawyer, under the guise of voir dire, makes

what seem to be comments on the law or facts in the case." Id. Gray

warns that "[s]uch commentary during voir dire risks incomplete or

inaccurate statements and may conceivably lead to confusion." Id.

The concerns raised by Gray were avoided when

the trial court prevented defense counsel's discussions about the

requirements of first-degree murder. The court's proposed solution--asking

"Can you give life without probation and parole if you find him guilty

of first degree murder[?]"--adequately permitted defense counsel to

determine if venirepersons could consider a life sentence in the case.

The trial court did not abuse its discretion in

sustaining the prosecutor's objections to defense counsel's questions

during voir dire. Having found no abuse of discretion, this Court need

not consider the issue of prejudice. This point is denied.

C. Evidence of Uncharged Crimes

Johnson asserts that the trial court erred in

overruling his defense counsel's objections to testimony of ''uncharged

crimes of 'stalking' children in the days preceding his crime." He

argues that this evidence was inappropriate propensity evidence offered

as proof that he deliberated to kill Casey, which prejudiced his defense

of diminished capacity.

1. Admissibility

The trial court has broad discretion in determining

the admissibility of evidence. Glass, 136 S.W.3d at 507. The

trial court's ruling on the admission of evidence will be reversed only

if the court clearly abused its discretion. Zink, 181 S.W.3d at

72-73.

Generally, evidence of uncharged crimes, wrongs, or

acts is inadmissible for the purpose of showing the defendant's

propensity to commit such crimes. Morrow, 968 S.W.2d at 107.

Although evidence of prior misconduct is inadmissible to show propensity,

it is admissible if it is logically relevant, in that it has some

legitimate tendency to establish directly the accused's guilt of the

charges for which he is on trial, and legally relevant, in that its

probative value outweighs its prejudicial effect. State v. Bernard,

849 S.W.2d 10, 13 (Mo. banc 1993). An exception to the general rule that

evidence of uncharged misconduct is inadmissible "is recognized for

evidence of uncharged crimes that are part of the circumstances or the

sequence of events surrounding the offense charged." Morrow, 968

S.W.2d at 107. Evidence of uncharged crimes is admissible "to present

the jury a complete and coherent picture of the charged crimes and to

rebut [a defendant's] contention that he lacked the ability to

deliberate." Id.

Errors in admitting evidence require reversal only

when prejudicial to the point that they are outcome-determinative.

State v. Black, 50 S.W.3d 778, 786 (Mo. banc 2001). "A finding of

outcome-determinative prejudice expresses a judicial conclusion that the

erroneously admitted evidence so influenced the jury that, when

considered with and balanced against all evidence properly admitted,

there is a reasonable probability that the jury would have acquitted but

for the erroneously admitted evidence." Id.

2. Evidence Presented

Johnson argues that Angel's testimony was not legally

relevant because its probative value was outweighed by its prejudicial

effect and was not logically relevant because the alleged "stalking" was

unrelated and not similar to the charged offense of murdering Casey.

Johnson's arguments are unpersuasive. Angel testified

to events that occurred at Casey's home and on her street only two days

before her murder. The evidence countered Johnson's claims that he did

not deliberate before killing Casey. Angel's testimony was admissible

because it helped construct a complete and coherent picture of Casey's

murder by establishing the context for that offense. See Morrow,

968 S.W.2d at 107.

Moreover, Johnson fails to demonstrate there was

outcome-determinative prejudice from Angel's testimony. Her testimony

about seeing Johnson in the days before the murder, and the prosecutor's

few remarks about that testimony, pales in the presence of the other

evidence in the case. The jury heard evidence of Johnson's confession

that he intended to take Casey for the purpose of having sex with her

and then kill her. He admitted to taking Casey to an isolated location,

burying her body, and attempting to wash evidence from his body. One of

Johnson's experts testified on cross-examination that having a mental

illness does not necessarily prevent a person from deliberating, and the

State's expert witness in rebuttal testified that Johnson was capable of

deliberating on the day of Casey's murder. There is no reasonable

probability that, but for the evidence that Johnson contests, the jury

would have acquitted him.

D. Voluntary Intoxication Instruction

Johnson asserts that the trial court erred in

submitting a voluntary intoxication instruction, Instruction 6, to the

jury over his objections. He alleges the instruction was not supported

by substantive evidence. He argues that the instruction misled jurors to

believe that his defense was an intoxicated or drugged condition at the

time of the crime, prejudicing his true defense of diminished capacity.

1. Preservation of the Issue

Johnson's arguments on appeal are limited to those he

stated at trial. State v. Johnson, 483 S.W.2d 65, 68 (Mo. 1972).

An appellant cannot broaden the scope of his objections on appeal beyond

that made in the trial court. State v. Lindsey, 80 S.W.2d 123,

125 (Mo. 1935) (internal citations omitted). A point is preserved for

appellate review only if it is based on the same theory presented at

trial. See State v. Barnett, 980 S.W.2d 297, 303 (Mo. banc 1998).

Unpreserved issues can be reviewed only for plain error. Glass,

136 S.W.3d at 507.

At trial, defense counsel argued that Instruction 6

was inconsistent with the diminished capacity instruction because the

evidence showed that Johnson's drug use produced psychosis. On appeal,

Johnson argues that there was not substantive evidence of intoxication

to support giving Instruction 6, particularly because evidence of

intoxication from statements Johnson made to experts was not admissible

as substantive evidence. These arguments on appeal were not raised at

trial or in Johnson's motion for new trial.

Johnson argues that, although his arguments at trial

and on appeal differ, this point was sufficiently preserved for review

because the prosecutor's response to his objection at trial discussed

the issue of the evidence presented. He asserts that the prosecutor's

arguments formed the basis for the trial court's ruling on his objection

and cites State v. Wandix, 590 S.W.2d 82, 84 (Mo. banc 1979), for

the proposition that an issue is sufficiently preserved where the record

reflects that the trial court and both parties recognized the issue

during the trial.

The trial court, however, did not state a specific

basis for rejecting Johnson's objection as to Instruction 6. The record

does not reflect that it considered the issue of whether there was

substantive evidence to support giving the instruction.

Johnson's arguments as to Instruction 6 are reviewed

only for plain error because they were not properly preserved for review.

2. Plain Error Review

Plain error is found only where the alleged error

establishes substantial grounds for believing a manifest injustice or

miscarriage of justice occurred. State v. Baker, 103 S.W.3d 711,

723 (Mo. banc 2003). "To establish that [an] instructional error rose to

the level of plain error, appellant must demonstrate that the trial

court so misdirected or failed to instruct the jury that it is evident

that the instructional error affected the jury's verdict." Id.

Johnson argues that giving Instruction 6 resulted in

manifest injustice because it suggested that his defense was an

intoxicated condition at the time of the crimes, which distracted jurors

from his defense that he was unable to deliberate. He argues that the

distraction from Instruction 6 was compounded by the evidence of drugs

and alcohol before the jury. Given that this evidence was presented,

however, the trial court did not err, plainly or otherwise, in providing

an instruction to clarify the jury's consideration of that evidence.

Johnson is not entitled to relief on this point.

E. Statements to Detective Newsham

Johnson alleges that the trial court erred in

overruling his motion to suppress statements he made to Detective

Newsham because the statements were unreliable and involuntary. He

maintains that the admission of the statements prejudiced him because

they provided direct evidence of deliberation.

1. Standards for Review

A trial court's ruling on a motion to suppress is

reviewed to determine if it is supported by substantial evidence, and it

will be reversed only if it is clearly erroneous. Edwards, 116

S.W.3d at 530. The evidence is viewed in the light most favorable to the

trial court's ruling and deference is given to the trial court's

determinations of credibility. Id.

2. Reliability

Johnson argues that the trial court should have

suppressed the statements because they were unreliable insofar as

Detective Newsham's account of when the statements were made conflicted

with jail records. He suggests that this conflict demonstrates that

Detective Newsham gave false testimony. This argument questions the

credibility of a witness. The trial court has the "superior opportunity

to determine the credibility of witnesses," and this Court defers to the

trial court's factual findings and credibility determinations. State

v. Rousan, 961 S.W.2d 831, 845 (Mo. banc 1998). The trial court did

not clearly err in refusing to suppress Detective Newsham's testimony

about Johnson's statements on the grounds of reliability.

3. Voluntariness

Johnson further alleges that the statements should

have been suppressed because they were involuntary. Johnson argues that

his statements were coerced by Detective Newsham's comments on eternal

salvation and were made after he had been in police custody for about 16

hours. In support of his coercion arguments, Johnson states that he

failed to complete ninth grade and was in need of medication for his

mental illness at the time the statements were made.

A challenge to the admissibility of a statement on

the grounds that it was involuntary puts the burden on the State to show

voluntariness by a preponderance of the evidence. Id. The test

for voluntariness is whether, under the totality of the circumstances,

the defendant was deprived of free choice to admit, to deny, or to

refuse to answer and whether physical or psychological coercion was of

such a degree that the defendant's will was overborne at the time he

confessed." Id. Factors that are considered include whether the

defendant was advised of his rights and understood them, the defendant's

physical and mental state, the length of questioning, the presence of

police coercion or intimidation, and the withholding of physical needs.

Id. "Evidence of the defendant's physical or emotional condition

alone, absent evidence of police coercion, is insufficient to

demonstrate that the confession was involuntary." Id.

Detective Newsham's comments about eternal salvation

were not improperly coercive. The comments arose from a discussion about

reading and came after Johnson's inquiry about achieving eternal

salvation. Detective Newsham's comments were not "threats of harm or

promises of worldly advantage" that would render Johnson's confession

inadmissible. See State v. Williamson, 99 S.W.2d 76, 79-80 (Mo.

1936) (Promises yielding involuntary confessions must be "promises of 'worldly

advantage,' as distinguished from adjurations of a moral or spiritual

nature; and they must be direct, as distinguished from collateral.").

Additionally, Johnson repeatedly waived his rights

before making statements throughout the day and did so again before

being further questioned by Detective Newsham. Johnson was not

questioned constantly throughout the day and he does not allege that he

was deprived of his physical needs. Johnson's interview with Detective

Newsham lasted only about 20 minutes and was followed by a taped

interview lasting only eight minutes. Detective Newsham testified that

Johnson did not indicate that he was under any physical, emotional, or

mental stress during their conversation, and he did not answer any

questions inappropriately.

The totality of the circumstances do not indicate

that Johnson's will was overborne at the time he confessed and the trial

court did not err in finding that his statements to Detective Newsham

were voluntary.

This point is denied.

F. Statutory Aggravator

Johnson alleges that the trial court erred in

submitting Instruction 23 over his objections because it included the "depravity

of mind" statutory aggravator, which he argues is "unconstitutionally

vague." He contends that he was prejudiced by the vagueness of this

aggravator because, had it not been given, the jury would have weighed

the aggravating and mitigating factors differently and not recommended

the death penalty.

1. Vagueness

Instruction 23 instructed the jury to consider:

Whether the murder of [Casey] involved depravity of

mind and whether, as a result thereof, the murder was outrageously or

wantonly vile, horrible or inhuman. You can make a determination of

depravity of mind only if you find: That the defendant committed

repeated and excessive acts of physical abuse upon [Casey] and the

killing was therefore unreasonably brutal." MAI-CR3d 313.40; section

565.032.2(7).

The limiting language in this instruction, which

explains what is required for a determination of "depravity of mind," is

taken from the Notes on Use for MAI-CR3d 313.40. See MAI-CR3d

313.40, Note 6(B)[2].

This Court has repeatedly held that the depravity of

mind language and limiting instruction, as represented in Instruction

23, provide sufficient guidance to sentencing jurors such that the

instruction is not unconstitutionally vague. Johns, 34 S.W.3d at

115; State v. Knese, 985 S.W.2d 759, 778 (Mo. banc 1999);

State v. Ervin, 979 S.W.2d 149, 166 (Mo. banc 1998); State v.

Butler, 951 S.W.2d 600, 605-06 (Mo. banc 1997); State v. Tokar,

918 S.W.2d 753, 772 (Mo. banc 1996).

2. Limiting Language

Johnson, however, contends that use of the limiting

language is not a cure for the aggravator's vagueness. He argues that

the addition of the limiting language improperly usurps legislative

power because it adds requirements to section 565.032.2(7) that are not

included in the statute. He also maintains that the limiting language

wrongly results in judicial fact-finding.

These arguments are without merit. The use of

limiting language to clarify the requirements of the statutory

aggravator is not an effort by the courts to engage in legislation. The

limiting language gives meaning to the words used in the statute and

ensures that the statute is constitutionally applied. This is statutory

construction, which is clearly in this Court's purview. Further, use of

the limiting language does not result in judicial fact-finding. The

language expressly instructs the jury to determine if "depravity of mind"

was involved based on the evidence in the case.

G. Penalty Instructions

Johnson alleges the trial court erred in giving

Instructions 24 and 26 over his objections because they failed to

properly instruct the jury how to weigh the aggravating and mitigating

factors.

This Court will reverse on a claim of instructional

error only if there was error in submitting an instruction and it

prejudiced the defendant. Zink, 181 S.W.3d at 74. MAI

instructions are presumptively valid and, when applicable, must be given

to the exclusion of other instructions. Id.

1. Instructions

Johnson complains that the instructions were given in

error and prejudiced him because they failed to tell the jury what to do

if they were tied or not unanimous when weighing aggravators and

mitigators. He fails to demonstrate that the instructions were

insufficient in this regard.

Instruction 24 was patterned after MAI-CR3d 314.44.

It stated in relevant part:

If you have unanimously found beyond a reasonable

doubt that one or more of the statutory aggravating circumstances

submitted . . . exists, you must then determine whether there are facts

and circumstances in aggravation of punishment.

. . . .

It is not necessary that all jurors agree upon

particular facts and circumstances in mitigation of punishment. If each

juror determines that there are facts or circumstances in mitigation of

punishment sufficient to outweigh the evidence in aggravation of

punishment, then you must return a verdict fixing defendant's punishment

at imprisonment for life . . . without eligibility for probation or

parole.

Instruction 26 was based on MAI-CR3d 314.48. It

stated in relevant part:

If you unanimously decide that the facts or

circumstances in mitigation of punishment outweigh the facts and

circumstances in aggravation of punishment, then the defendant must be

punished for the murder . . . by imprisonment for life . . . without

eligibility for probation or parole . . . .

. . . .

If you do unanimously find the existence of at least

one statutory aggravating circumstance beyond a reasonable doubt . . .

and you are unable to unanimously find that the facts or circumstances

in mitigation of punishment outweigh the facts and circumstances in

aggravation of punishment, but are unable to agree upon the punishment,

your foreperson will complete the verdict form . . . . [And] you must

answer the questions on the verdict form . . . .

Johnson also asserts that these instructions

prejudiced him because they failed to inform the jury about the proper

burden of proof for weighing mitigators against aggravators. He argues

that under section 565.030.4(3), the third of four steps for determining

whether a defendant is eligible for the death penalty, the jury must be

instructed that the State bears the burden of proving beyond a

reasonable doubt that the mitigators are insufficient to outweigh any

aggravators found.

This Court has repeatedly rejected the claim that

section 565.030.4(3) requires the jury to make a finding beyond a

reasonable doubt. State v. Gill, 167 S.W.3d 184, 193 (Mo. banc

2005) ("Although section 565.030.4 expressly requires the jury to use

the reasonable doubt standard for the determination of whether any

statutory aggravators exist, the statute does not impose the same

requirement on the determination of whether evidence in mitigation

outweighs evidence in aggravation."); Glass, 136 S.W.3d at 521;

see also Storey v. State, 175 S.W.3d 116, 156-57 (Mo. banc

2005).

2. Plain Error Review

Johnson further requests plain error review of

Instructions 24 and 26 on his claims that the instructions were given in

error because section 565.030.4(3) requires that only aggravators "found"

by the jury be considered and because section 565.030.4(3) does not

require the jury to "unanimously" find that mitigators outweigh

aggravators. An instructional error rises to the level of plain error

only when the appellant demonstrates that the instruction so misdirected

or failed to instruct the jury that it is apparent that the error

affected the jury's verdict. Baker, 103 S.W.3d at 723. Johnson

fails to meet this burden.

This point is denied.

H. Statutory Aggravating Circumstances

Johnson contends that the trial court erred in

overruling his motion to quash the information or, alternatively,

preclude the death penalty because the State's amended information was

insufficient in that it failed to plead any statutory aggravators.

Johnson's claim is based on his belief that Apprendi v. New Jersey,

530 U.S. 466 (2000), and Ring v. Arizona, 536 U.S. 584 (2002),

require statutory aggravators to be included in the charging document so

that the offense of aggravated first-degree murder, punishable by death,

is distinguished from the offense of non-aggravated first degree murder,

which would have a maximum sentence of life without parole.

1. Inclusion in Information Not Required

This Court has repeatedly rejected claims that the

information or indictment must include statutory aggravators. See,

e.g., Gill, 167 S.W.3d at 193-94;(FN20) Glass, 136 S.W.3d at

513; Edwards, 116 S.W.3d at 543-44 (Mo. banc 2003); State v.

Gilbert, 103 S.W.3d 743, 747 (Mo. banc 2003); State v. Tisius,

92 S.W.3d 751, 766-67 (Mo. banc 2002); State v. Cole, 71 S.W.3d

163, 171 (Mo. banc 2002). "Missouri's statutory scheme recognizes a

single offense of murder with a maximum sentence of death, and the

required presence of aggravating facts or circumstances to result in

this sentence in no way increases this maximum penalty." Gill,

167 S.W.3d at 194.

2. Notice is Sufficient

Section 565.005.1 requires the state to give the

defendant notice "[a]t a reasonable time before the commencement of the

first stage of [a capital trial]" of the statutory aggravating

circumstances it intends to submit in the event the defendant is

convicted of first degree murder. "Notice of statutory aggravating

circumstances stands in lieu of charging them in the information or

indictment." Glass, 136 S.W.3d at 513. Johnson does not allege

that he had insufficient notice of the statutory aggravating

circumstances in this case.

The trial court did not error in overruling Johnson's

motion to quash the information.

I. Closing Arguments

Johnson seeks plain error review of his claim that

the trial court erred in failing to admonish the prosecutor and give

corrective instructions to the jury when the prosecutor remarked in his

closing argument that the jury should "for once" hold Johnson

responsible for his misconduct.(FN21) Johnson contends that these

remarks improperly asked the jury to base its findings on and punish him

for uncharged bad acts. He asserts that the prosecutor's argument

wrongly relied on information obtained by mental competency examiners

that was prohibited from being used as substantive evidence under

sections 552.030.5 and 552.020.14.

1. Plain Error Review of Closing Arguments

"Statements made in closing argument will rarely

amount to plain error, and any assertion that the trial court erred for

failure to intervene sua sponte overlooks the fact that the absence of

an objection by trial counsel may have been strategic in nature."

Cole, 71 S.W.3d at 171. Plain error relief is seldom granted on

assertions of error relating to closing argument because absence of an

objection and request for relief during closing argument means that any

intervention by the trial court would have been uninvited and may have

caused increased error. State v. Silvey, 894 S.W.2d 662, 670 (Mo.

banc 1995). Johnson's plain error claims relating to closing arguments

need not be considered unless he shows "there is a sound, substantial

manifestation, a strong, clear showing, that injustice or miscarriage of

justice will result if relief is not given." State v. Wood, 719

S.W.2d 756, 759 (Mo. banc 1986) (internal citations omitted).

It is not necessary to determine the propriety of the

prosecutor's closing remarks in this case. When manifest injustice is

the standard, improper argument results in reversal of a conviction only

if it is established that the argument in question had a decisive effect

on the jury's determination. State v. Wren, 643 S.W.2d 800, 802 (Mo.

banc 1983). The defendant bears the burden to prove the decisive

significance. State v. Parker, 856 S.W.2d 331, 333 (Mo. banc

1993). In light of the evidence presented in this case, Johnson fails to

show how the prosecutor's comments had a decisive effect on the jury's

verdict.

J. Proportionality Review

Johnson asserts the trial court erred in overruling

his new trial motion and sentencing him to death because the death

sentence in this case is excessive, unreliable, and disproportionate.

This claim is addressed as part of this Court's independent

proportionality review pursuant to section 565.035.3, which requires

this Court to determine:

(1) Whether the sentence of death was imposed under

the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor; and

(2) Whether the evidence supports the jury's or

judge's finding of a statutory aggravating circumstance as enumerated in

subsection 2 of section 565.032 and any other circumstance found;

(3) Whether the sentence of death is excessive or

disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar cases, considering

both the crime, the strength of the evidence, and the defendant.

Section 565.035.3.

1. Influence of Prejudice

Johnson argues that the trial court's "serious and

prejudicial errors" during both the guilt and penalty phases improperly

influenced the jury's verdict and undermined the reliability of the

death sentence. As articulated above, however, this Court has found no

errors. The non-errors alleged by Johnson did not improperly influence

the jury's imposition of the death penalty. Having reviewed the record,

this Court finds no evidence suggesting that the punishment imposed was

a product of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor.

2. Aggravating Factors

This Court next reviews the trial court's findings to

determine if the evidence supports, beyond a reasonable doubt, the

existence of an aggravating circumstance and any other circumstance

found. The jury found three statutory aggravating circumstances as

grounds for considering the death sentence. The jury found that the

murder was outrageously or wantonly vile, horrible, or inhuman in that

it involved depravity of mind. Section 565.032.2(7). It also found that

the murder was committed while Johnson was engaged in committing the

offenses of kidnapping and attempted forcible rape. Section

565.032.2(11).

The evidence supports, beyond a reasonable doubt,

that Casey's murder was wantonly vile, horrible, or inhuman in that it

involved depravity of mind. The jury was instructed that it could make a

determination of depravity of mind only if it found Casey's murder was

unreasonably brutal because Johnson committed repeated and excessive

acts of physical abuse on Casey. The evidence supports such a finding.

Casey's head was repeatedly struck with a brick before Johnson dropped a

"boulder" on her head.

The evidence also supports, beyond a reasonable doubt,

a finding that Johnson murdered Casey while he was engaged in the

commission of the offenses of kidnapping and attempted forcible rape.

3. Proportionality

Finally, this Court must consider whether the

sentence of death is excessive or disproportionate to the penalty

imposed in similar cases, considering the crime, the strength of the

evidence, and the defendant. Johnson maintains that the analysis of "the

strength of the evidence and the defendant" must include consideration

of the evidence that he was unable to deliberate because he suffers from

severe mental illness. He contends that, although the jury found his

mental illness "did not diminish his capacity to deliberate, and thus

the evidence on that issue may be sufficient to support his conviction

for murder," the evidence does not satisfy the Eight Amendment's

requirements for imposing the death penalty. He asserts that the

evidence showed that his severe mental illness impaired his ability to

reason and control his conduct in the same manner as an offender who

suffers from mental retardation, such that he should not be sentenced to

death under Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002) (execution of

the mentally retarded criminal is "cruel and unusual punishment"

prohibited by the Eighth Amendment). Johnson further argues that the

mitigating evidence of his mental illness weighed against imposition of

the death penalty.

The jury rejected Johnson's mental illness defenses

and arguments in both the guilt and penalty phases of the trial. Both

federal and state courts have refused to extend Atkins to mental

illness situations. In re Nelville, 440 F.3d 220,223 (5th

Cir. 2006); State v. Hancock, 840 N.E.2d 1032, 1059-60 (Ohio

2006). There is nothing in the record of this case that would justify a

different course of action.

Johnson urges this Court to consider that a death

sentence is disproportionate in his case because other defendants

charged with first-degree murder of a child victim have not been

sentenced to death. In determining whether the sentence of death is

disproportionate compared to similar cases, however, comparison is made

to other cases wherein the death penalty was imposed. Lyons v. State,

39 S.W.3d 32, 44 (Mo. banc 2001).

This Court has upheld the death sentence in other

cases where the defendant presented evidence of mental illness. See,

e.g., State v. Taylor, 134 S.W.3d 21, 25, 31 (Mo. banc 2004)

(paranoid schizophrenia); State v. Anderson, 79 S.W.3d 420, 429,

447 (Mo. banc 2002) (severe depression and extreme paranoia); State

v. Harris, 870 S.W.2d 798, 819 (Mo. banc 1994) (post-traumatic

stress syndrome).

The death penalty has also been upheld in cases where

the murder involved brutality and abuse that demonstrated depravity of

mind. See, e.g., Strong, 142 S.W.3d at 728; Williams, 97

S.W.3d at 475; Cole, 71 S.W.3d at 177; Knese, 985 S.W.2d

at 779.

The death sentence is consistent with the punishment

imposed in other cases where the defendant abducted a young victim and

then sexually abused and murdered the victim. See, e.g., Glass,

136 S.W.3d at 521; State v. Ferguson, 20 S.W.3d 485, 511 (Mo.

banc 2000); State v. Brooks, 960 S.W.2d 479, 502 (Mo. banc 1997).

This case involves the heinous killing of a small

child. Johnson admitted that he kidnapped six-year old Casey Williamson

and took her to a pit in an abandoned factory. He admitted that he

attempted to rape her, struck her head repeatedly with a brick, and

dropped a boulder on her head. He admitted that after she stopped

breathing he covered her body with rocks and debris and then went to the

river to wash away the evidence of his crimes. The death sentence in

this case is neither excessive nor disproportionate compared to the

penalty imposed in similar cases.

IV. Conclusion

The judgment is affirmed.

All concur.