Mysanantonio.com

February 19, 2008

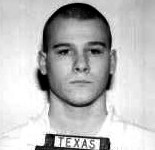

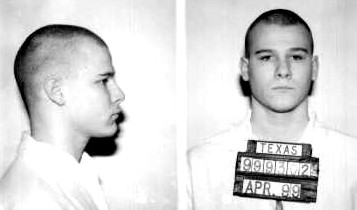

LIVINGSTON He has the fresh face and budding

vocabulary of a college sophomore, this convict who kidnapped and

killed before he reached age 18.

He reads the dictionary and drops big words

into conversation like cacophony, copious and

manifest, but Leo Gordon Little III's most striking statement

is a simple one.

"I like life even in here," says death row

inmate No. 999302, once a wannabe Crip from San Antonio who shot a

young ministerial worker in 1998.

Now 24, Little talks about studying language,

math, history and religion discovering the world from inside a

5-foot-wide cell even as the nation debates whether it's

acceptable to execute him and 71 other killers condemned as

juveniles.

The U.S. Supreme Court could decide as soon as

Tuesday whether capital punishment should apply to criminals who

were so young when they lashed out that their brains may not have

been fully developed.

The case of the Missouri convict Christopher

Simmons is the oldest on the court's docket a sign that the

justices, who are often split when it comes to the death penalty,

may again be sharply divided.

Always a polarizing topic, the death penalty

debate only intensifies when it comes to kids who kill. It pits

parental instincts against the demands of justice and in the

process raises tough questions in the murky middle ground between

science and ethics.

Texas has conducted most of the country's

juvenile executions nearly two-thirds in the past 30 years.

And it has joined Missouri and six other states in defending the

practice at the Supreme Court.

The ruling could spare two juvenile offenders

from Bexar County. One is Randy Arroyo, who at 17 carjacked an Air

Force captain and, according to testimony, told his friend to

shoot when the officer tried to escape.

Leo Little is the other.

Whether Little should live or die seemed a

relatively simple question when it was posed to Bexar County

jurors on March 5, 1999.

Little's crime eclipsed his age, said one of

the defense lawyers, Jeff Scott.

"He stalked this guy and led him around town,

made him use his credit card to buy gas, then took him out and

shot him in the middle of nowhere and then drug him off the side

of the road so nobody would find him.

"And when someone did find him the next morning,

the poor kid was still alive and, all night long, had been trying

to get up," Scott said.

Adolescent brains

The Supreme Court reinvigorated the debate over

the juvenile death penalty two years ago when a narrow majority of

justices decided it was cruel and unusual to execute mentally

retarded murderers.

Convinced that the nation had come to view

mentally retarded convicts as less culpable than the average

criminal, the justices opened the door to similar arguments about

juveniles.

For one, research has shown that the parts of

the brain in charge of impulse control, judgment and mature

reasoning aren't fully developed in late adolescence perhaps why

drivers between 16 and 19 are most at risk of accidents.

Secondly, opponents cited several figures to

argue that national support for executing juveniles had eroded in

recent years. For example:

The 19 states with capital punishment for

juveniles have applied it less often. Only two adolescents were

sent to death row in 2003 a decline considered significant even

after taking into account the falling murder rate.

Just three states Texas, Virginia and

Oklahoma have actually executed a juvenile offender in the last

11 years.

The cause of the decline is unclear. One study

found small but statistically significant evidence that, when

wrongful convictions came to light, death sentences for juveniles

decreased.

Whatever the reasons behind the decline, its

message is clear, according to some opponents of capital

punishment for juveniles.

"It goes to show people don't want to do it

anymore," says Stephen Harper, an expert on the juvenile justice

system who teaches at the University of Miami School of Law.

Skeptics say death-penalty opponents overstate

the trends and scientific findings.

The research also shows that brains are

generally almost 95 percent complete by age 17.

While parts of the brain that control impulses

and measure risks versus rewards may still be developing in

adolescents, 17-year-olds are advanced enough to understand morals

basic right and wrong.

"A moral sense is one of the first things to

develop," said Jerome Kagan, a Harvard University psychology

professor. "Five-year-olds know killing is wrong."

The science is also inexact. Some brains

develop faster than others.

Accordingly, juveniles should be evaluated

individually, said Robert Blecker, a New York University law

professor who supports capital punishment for only the worst

slayings.

Take for example, he said, Mark Anthony Duke of

Alabama.

According to Alabama prosecutors, Duke was 16

and tired of being bossed around when he arranged the quadruple

murder of his dad, his dad's girlfriend and her daughters, ages 6

and 7.

Duke's crime "shows careful planning,

callousness, a depravity that unquestionably marks him as one of

the worst," Blecker said.

Bexar County case

There are those who might say the same of Leo

Gordon Little. But at first, he just seemed to be a troubled kid.

Sometime after his dad left when he was 10, the

boy known as Gordy became the angry, depressed and explosive loner

described at 13 in an evaluation by school psychologists.

Though his IQ was average at 91, he was labeled

"emotionally disturbed" and put in special education classes at

Sul Ross Middle School.

Years later, after the murder, his anguished

mother would rack her brain trying to understand the violence in

her son: Was he furious at his father's withdrawal?

Was he angry that her work as an insurance

clerk left little time for attending to three children? Or was he

damaged by blows to the head once when a baby sitter dropped him

as a baby and once when his sister hurled a sugar jar at him?

As a teenager, he gouged holes in walls at home

and, according to court documents, punched a sister in the head

and threatened his mom with a knife.

"I have a big temper," he was quoted as saying.

"When somebody gets me mad I go wild ..."

He exemplified findings of a recent study of

juveniles on Texas' death row: 13 of 18 evaluated were identified

as having had emotional problems by sixth grade.

While the study, led by Yale psychiatrist Dr.

Dorothy Otnow Lewis, found that 15 of 18 showed signs of serious

mental illnesses while in prison, only four of 18 had undergone

psychiatric examinations before trial.

Back in 1993, Northside School District's

report recommended Little be put in therapy he never was and

predicted gang involvement, drug use and trouble with the law.

Arrests for shoplifting and trespassing soon

followed. As did experimentation with drugs. First marijuana and

later cocaine, heroin, acid and at least one toke of crack.

When the dope ran out, Little inhaled whatever

he could find kerosene, gasoline, spray paint, lighter fluid,

felt markers, air freshener, White Out, Freon and nitrous oxide.

Inhalants are known to cause at least mild

brain damage.

In Little's case, what's certain is this: Drugs

kept him from following his father's footsteps into the Marine

Corps. He tried to enlist but failed the drug test.

Rejected by the military, Little joined a gang

of sorts. He was given the name Li'l Crazy. He painted his room

blue, the gang's color, and began filling a notebook with rap

lyrics:

I may be small but I'm (expletive) crazy

Been smoking herb and my mind is kind of hazy

With all that (expletive) filling up my head,

as a Crip,

I'm always ready to kill mother (expletive)

dead.

Looking back, Little's mom, who asked that her

name not be published to avoid embarrassment at work, says, "I

would've been more alert. I would've brought myself out of the

dark ages and educated myself more on things to look for. I

would've paid more attention to him."

Little's father shares some of the same regret.

Leo Gordon Little Jr. says his job as a bus

driver too often took him away from his children. And, even when

he was home, he would let long stretches pass without seeing his

son.

When they did spend time together, the father

found the adolescent surly and beyond reach; he seemed to have a

warped concept of life too common among teenagers.

"They think life is a Nintendo game where if

someone gets killed, you press restart and they pop up again," he

said.

Juries and death sentences

Perhaps no one can articulate the terror

wreaked by Leo Little better than Malachi Wurpts.

A week before Little became a killer, Wurpts

woke up around 2 a.m. to find the teenager standing at the foot of

his bed and pointing a gun at him.

The 25-year-old computer programmer had

returned from the airport a few hours earlier and, exhausted from

traveling, forgot to lock his door.

Little forced Wurpts to drive from his gated

Medical Center-area apartment complex to two ATMs and withdraw

$400.

Then, with a small silver .25-caliber automatic

pistol stuck into Wurpts' side, Little guided him to a rural area

and left him there, ditching his burglarized car more than a mile

away and fleeing with an accomplice.

To Wurpts, Little didn't seem high on drugs.

Wearing a baseball cap pulled low, the gunman seemed forceful and

intent.

Wurpts prayed silently and obeyed as Little

barked orders: Get up. Get dressed. Don't look at me.

"If I get caught, I'm not going down for

robbery," Wurpts remembered Little warning him. "I'm going down

for murder."

Prosecutors and jurors were willing to oblige

that wish when Little was charged with the January 1998 kidnapping

and slaying of Antonio Christopher Chavez, a 22-year-old

ministerial servant for a Jehovah's Witnesses congregation.

The trial featured testimony from friends

Little visited after the slaying, videotape of Little with Chavez

in a convenience store and Little's own confession.

An acquittal seemed out of the question. The

defense lawyers hoped only to spare Little the death penalty and,

during the trial's punishment phase, he took the stand to

apologize.

"I didn't want to hurt him," Little told

Chavez's family. "Something took over me that night."

The jurors were not impressed. Not by Little's

remorseful words. Or by his baby face.

What stuck most in their minds, several jurors

recalled, was how the videotape showed a dark blotch on Chavez's

gray slacks. The victim was so scared he had lost control of his

bladder.

Chavez's mother said the family couldn't bear

to discuss the tragedy yet again. Six months ago, Antonio Chavez

Sr. spoke with a reporter about his grief.

"The pain and agony never leaves," Chavez said.

"Time only helps you adjust and cope with that pain. It never

eliminates it."

Age was not mentioned during the deliberations.

No juror believed Little would change, said one of the jurors,

Daniel Mere.

"It felt like Mr. Little had no remorse

whatsoever," he said. "The whole case he sat there and basically

he had that kind of thug-punk attitude."

It was different at Randy Arroyo's trial.

Several jurors were crying when they returned with death sentences

for the skinny and bookish Arroyo and his accomplice, Vincent

"Flaco" Gutierrez, who was the shooter.

Gutierrez was 18 when they carjacked Air Force

Capt. José Renato Cobo in March 1997 and left the officer dying in

the rain and morning rush-hour traffic on Loop 410.

During deliberations, two jurors argued that

Arroyo deserved a life sentence because he was young. One, Leticia

Puente, reluctantly changed her mind because of sentencing

guidelines:

If someone's found to be a continuing threat to

society and there aren't mitigating circumstances, Texas law

demands the death penalty.

"That trial was the hardest thing I've ever

done," said Puente, 48, then a Wal-Mart sales clerk who suffered

stress-related nosebleeds throughout the trial.

Other jurors ganged up on the lone holdout, a

schoolteacher, until she relented, Puente said.

Arroyo's mother died of AIDS when he was 12 and,

according to his brother and sister, his father was an alcoholic.

"I really didn't have no teenage years for the

simple fact that my mother passed away, so I was growing up by

myself," Arroyo said in a death row interview last week. "When I

first moved into my neighborhood, our clothes were stolen off the

clothesline. So the mentality is, 'Well, I'm going to steal it

right back.' There's no, 'Well, I'll feel sorry for him,' when I'm

doing so bad already, I'm down on my knees."

'The right factors'

Six years after Leo Little arrived on death row,

there is no sign of the thug who chose a stranger at random and

killed him at least not when a reporter and photographer come to

visit.

The thick plastic window of the visiting booth

reveals only a thin young man in a worn white shirt who unlike

many other inmates readily admits his guilt.

Without visible emotion, he acknowledges that

he killed Chavez but says he's a different person today and is

still discovering himself.

"I have a lot more worth now that I've had a

change in mindset now that I've been given the opportunity over

these past six years to reflect on my behavior, to reflect on the

rights and wrongs of a man in society," he says.

Sounding at times like a philosophy major

puzzling out new ideas, he tries explaining why he squeezed the

trigger.

He had few influences as a child, he says. Had

anyone encouraged him, he might have tried to become a chef.

Instead, he latched onto gangster rap and pals who wanted to live

the lyrics.

Soon, he was one more white suburban kid aping

the bravado of rappers with flashy jewelry and long limousines.

"I didn't have the money, the copious amounts

of money they brag about," he said. "So the next best thing was a

gun."

Once the weapon was in his hand, it was the

final ingredient, mixing with the music and drugs like an

intoxicating cocktail.

After that, it didn't take much.

"You don't need any reasonable reason to flick

your finger, you know, it's real simple. It doesn't need a

philosophy behind it. It doesn't need a why. It happens if the

right factors are present," he said.

The factors fell in place on Jan. 22, 1998,

seven days after he and a friend had left Wurpts, alive but

stranded, on the side of a country road.

Rap songs were ringing in his ears. Cocaine,

marijuana and mescal were flowing through his arteries. Little and

his pal José Zavala began the search for a new victim.

They had stopped to use the restroom at

Maggie's Restaurant on San Pedro Avenue when Little saw a well-dressed

young man go to his car, deposit a bag and return to the

restaurant.

Little scrawled a note to Zavala follow the

blue car behind us and crawled into the back seat of the man's

car.

About 10 minutes later, Christopher Chavez

finished dinner with other members of his congregation and

returned to his car without noticing the passenger.

The car had barely left the parking lot when

Little emerged from the shadowy back seat with a gun. They went

first to Chavez's apartment, then to get gas. They drove southeast

for about an hour.

Chavez did as Little commanded until they came

to a stop on an empty stretch of Old Sutherland Springs Road, not

far from where Little had briefly lived with his father.

There, Li'l Crazy marched Chavez in front of

the headlights and told him to kneel so that he faced away from

the gun.

Aiming at the back of Chavez's head, Little

pulled the trigger three times. Fear and excitement mixed with the

stimulants in his system.

With Zavala's help, he dragged Chavez away from

the road, over rocks and weeds to a spot near a barbed-wire fence.

Leaving Chavez to die slowly he would survive

another two days the teenagers took the car and headed to a

nearby friend's house.

There, Little would strip the car of its stereo

and, the next day, he would spend Chavez's money on a new set of

tires.

But first, upon arriving at his friend's house,

he played Nintendo.