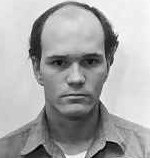

Arizona death row inmates

Walter and Karl LaGrand appeal the district

court's denial of their petitions for writ

of habeas corpus. We have jurisdiction of

these consolidated appeals pursuant to 28

U.S.C. § 1291, and we affirm.

I

* FACTS AND PROCEDURAL

HISTORY

Walter

LaGrand (Walter) and Karl LaGrand (Karl) (collectively

"the LaGrands") were each convicted of first-degree

murder, attempted murder in the first degree,

attempted armed robbery and two counts of

kidnapping. The Arizona Supreme Court gave

this account of the crimes in Walter's

appeal:

This case

arises from a series of events which

occurred during a bungled attempt to rob the

Valley National Bank in Marana, Arizona, on

January 7, 1982.

That

morning Walter and Karl LaGrand drove from

Tucson, where they lived, to Marana

intending to rob the bank. They arrived in

Marana sometime before 8:00 a.m. Because the

bank was closed and empty the LaGrands drove

around Marana to pass time. They eventually

drove to the El Taco restaurant adjacent to

the bank.

Ronald

Schunk, manager of El Taco, testified that

he arrived at work at 7:50 a.m. The moment

he arrived, a car with two men inside drove

up to the El Taco. Schunk described the car

as white with a chocolate-colored top. The

car's driver, identified by Schunk as Walter

LaGrand, asked Schunk when the El Taco

opened. Schunk replied, "Nine o'clock." The

LaGrands then left.

Dawn Lopez

arrived for work at the bank at

approximately 8:00 a.m. When she arrived at

the bank she noticed three vehicles parked

in the parking lot: a motor home; a truck

belonging to the bank manager, Ken Hartsock;

and a car which she did not recognize but

which she described as white or off-white

with a brown top.

Because

Lopez believed that Hartsock might be

conducting business and desire some privacy

she left the parking lot and drove around

Marana for several minutes. She returned to

the bank and noticed Hartsock standing by

the bank door with another man whom she did

not recognize. Lopez parked her car and

walked toward the bank entrance where

Hartsock was standing.

As she

passed the LaGrands' car Walter emerged from

the car and asked her what time the bank

opened. Lopez replied, "Ten o'clock." Lopez

continued walking and went into the bank.

When she entered the bank she saw Hartsock

standing by the vault with Karl LaGrand.

Karl was wearing a coat and tie and carrying

a briefcase.

Karl told

her to sit down and opened his jacket to

reveal a gun, which was later found by the

police to be a toy pistol. Walter then came

through the bank entrance and stood by the

vault. Lopez testified that Walter then said,

"If you can't open it this time, let's just

waste them and leave." Hartsock was unable

to open the vault because he had only one-half

of the vault combination.

The

LaGrands then moved Lopez and Hartsock into

Hartsock's office where they bound their

victims' hands together with black

electrical tape. Walter accused Hartsock of

lying and put a letter opener to his throat,

threatening to kill him if he was not

telling the truth. Lopez and Hartsock then

were gagged with bandannas.

Wilma

Rogers, another bank employee, had arrived

at the bank at approximately 8:10 a.m. Upon

arriving Rogers noticed two strange vehicles

in the parking lot and, fearing that

something might be amiss, wrote down the

license plate numbers of the two unknown

vehicles.

She then

went to a nearby grocery store and

telephoned the bank. Lopez answered the

phone after her gag was removed; her hands

remained tied. Karl held the receiver to

Lopez' ear and listened to the conversation.

Lopez answered the phone. Rogers asked for

Hartsock but Lopez denied that he was there,

which struck Rogers as odd because she had

seen his truck in the bank parking lot.

Rogers

then told Lopez that her car headlights were

still on, as indeed they were. Rogers told

Lopez that if she did not go out to turn her

headlights off, then she would call the

sheriff. A few minutes later Rogers asked

someone else to call the bank and they also

were told that Hartsock was not there.

Rogers then called the town marshal's

office.

After the

first telephone call the LaGrands decided to

have Lopez turn off her headlights. Her

hands were freed and she was told to go turn

off the lights but was warned that "If you

try to go-if you try to leave, we'll just

shoot him and leave. We're just going to

kill him and leave." Lopez went to her car

and turned off the lights.

Upon her

return to the bank her hands were retied.

Hartsock was still bound and gagged in the

same chair. Lopez was seated in a chair, and

turned toward a corner of the room. Lopez

testified that soon thereafter she heard

sounds of a struggle.

Fearing

that Hartsock was being hurt, Lopez stood

up, broke the tape around her hands and

turned to help him. Lopez testified that for

a few seconds she saw Hartsock struggling

with two men. Karl was behind Hartsock

holding him by the shoulders while Walter

was in front.

According

to Lopez, Walter then came toward her and

began stabbing her. Lopez fell to the floor,

where she could see only the scuffling of

feet and Hartsock lying face down on the

floor. She then heard someone twice say, "Just

make sure he's dead."

The

LaGrands left the bank and returned to

Tucson. Lopez was able to call for help.

When law enforcement and medical personnel

arrived at the bank Hartsock was dead. He

had been stabbed 24 times. Lopez, who had

also been stabbed multiple times, was taken

to University Hospital in Tucson.

Law

enforcement personnel quickly identified the

LaGrands as suspects. By 3:15 p.m., police

had traced the license plate number to a

white and brown vehicle owned by the father

of Walter's girl friend, Karen Libby. The

apartment where the LaGrands were staying

with Karen Libby was placed under

surveillance.

Shortly

thereafter Walter, Karl and Karen Libby left

the apartment and began driving. They were

followed and soon pulled over. Walter and

Karl were then arrested and the car was

searched. Karen Libby's apartment was also

searched and a steak knife similar to one

found at the bank was seized. Karl's

fingerprint was found at the bank. A

briefcase containing a toy gun, black

electrical tape, a red bandanna, and other

objects was found beneath a desert bush and

turned over to the police.

State v.

LaGrand, 153 Ariz. 21, 734 P.2d 563, 565-66

(1987).

When

questioned after their apprehension, Walter

made no statements, but Karl confessed to

the crimes in two different statements. He

stated that he had stabbed Hartsock and

Lopez, but that Walter had not stabbed

anyone and that Walter had been out of the

room at the time.

Following

a jury trial, both were convicted on all

charges. After considering mitigating and

aggravating circumstances,1

the judge sentenced both defendants to death.

The Arizona Supreme Court affirmed the

convictions and sentences. State v. Karl

LaGrand, 152 Ariz. 483, 733 P.2d 1066

(1987); State v. Walter LaGrand, supra. The

Supreme Court of the United States denied

certiorari. 484 U.S. 872, 108 S.Ct. 206, 98

L.Ed.2d 157 (1987).

The

LaGrands then filed post-conviction relief

petitions in the Arizona Superior Court (trial

court) which were denied in 1989. The

Arizona Supreme Court denied review as did

the United States Supreme Court. 501 U.S.

1259, 111 S.Ct. 2910, 2911, 115 L.Ed.2d 1074

(1991). The LaGrands then filed petitions

for writ of habeas corpus pursuant to 28

U.S.C. § 2254. The district court, in a

series of orders, denied relief, LaGrand v.

Lewis, 883 F.Supp. 469 (D.Ariz.1995),

LaGrand v. Lewis, 883 F.Supp. 451 (D.Ariz.1995),

and these timely appeals followed.

Additional

facts necessary to the discussion of the

several issues are contained in the portions

of this opinion in which the issues are

addressed.

Walter and

Karl raise a number of issues jointly, which

we discuss prior to reaching their

individual claims.

Two

related arguments are advanced relative to

the trial court's finding of expectation of

pecuniary gain as an aggravating factor.

First, the LaGrands contend that the finding

of pecuniary gain was arbitrary or

irrational. The trial court's finding was

affirmed by the Arizona Supreme Court in its

independent review. That court said:

We do not

believe the defendant must intend beforehand

to kill as well as to rob to satisfy the

statute. A.R.S. § 13-703(F)(5). Nor do we

believe that an absence of actual receipt of

money or valuables negates a finding of

expectation of pecuniary gain as an

aggravating circumstance.

In this

case, the attempted robbery permeated the

entire conduct of the defendant. The

defendant may have reacted irrationally to

the failure or inability of the victim to

open the safe but the murder was neither

accidental nor unexpected.

The reason

defendant was there was his expectation of

pecuniary gain and the reason he stabbed the

victim was because the victim was unable to

open the safe, frustrating defendant's

continuing attempt for pecuniary gain. The

defendant's goal of pecuniary gain caused

the murder and the murder was in furtherance

of his goal. We agree with the trial court's

finding that the defendant's expectation of

pecuniary gain was an aggravating factor.

State v.

LaGrand, 153 Ariz. at 36, 734 P.2d at 578 (footnote

omitted).

Lewis v.

Jeffers, 497 U.S. 764, 780, 110 S.Ct. 3092,

3102, 111 L.Ed.2d 606 (1990), a case arising

in Arizona, held that federal court review

of such a finding by the state court "is

limited, at most, to determining whether the

state court's finding was so arbitrary or

capricious as to constitute an independent

due process or Eighth Amendment violation."

The Court went on to say:

A state court's finding

of an aggravating circumstance in a

particular case-including a de novo finding

by an appellate court that a particular

offense is "especially heinous ... or

depraved"-is arbitrary or capricious if and

only if no reasonable sentencer could have

so concluded.

Id. at

783, 110 S.Ct. at 3103.

Here, the

sole purpose of the journey to the bank was

to rob it. The LaGrands threatened the

victims with death in order to obtain entry

to the vault. In fact, Walter LaGrand

admitted in his trial testimony that he held

a letter opener to Ken Hartsock's neck as a

threat. A rational sentencer could have

found the existence of the pecuniary gain

aggravating factor.

Second,

the LaGrands argue that the Arizona Supreme

Court broadened the definition of pecuniary

gain in violation of both the Due Process

Clause and the Ex Post Facto Clause of the

Constitution. Their basic argument is that

the Arizona Supreme Court, in saying that

the intent to rob "infects" all other

actions, "effectively wipes out any

requirement to prove the aggravating factor

beyond a reasonable doubt."

The Ex

Post Facto Clause does not apply to court

decisions construing statutes. "The Ex Post

Facto Clause is a limitation upon the powers

of the Legislature, see Calder v. Bull, 3

Dall. [U.S.] 386, 1 L.Ed. 648 (1798), and

does not of its own force apply to the

Judicial Branch of government." Marks v.

United States, 430 U.S. 188, 191, 97 S.Ct.

990, 992, 51 L.Ed.2d 260 (1977).

It is the

Due Process Clause, rather than the Ex Post

Facto Clause, which protects criminal

defendants against novel developments in

judicial doctrine. See, e.g., Bouie v.

Columbia, 378 U.S. 347, 84 S.Ct. 1697, 12

L.Ed.2d 894 (1964). See also United States

v. Ruiz, 935 F.2d 1033, 1035 (9th Cir.1991).

However, an unforeseeable judicial

construction of a statute may run afoul of

the Due Process Clause because of the same

policy underlying the Ex Post Facto Clause-lack

of "fair warning of that conduct which will

give rise to criminal penalties." Marks, 430

U.S. at 191, 97 S.Ct. at 992-93.

The

Arizona statutory scheme was clear in 1982.

The felony murder statute provided that

robbery or attempted robbery were predicate

felonies, and that the statute applied if,

"in the course of and in furtherance of such

offense or immediate flight from such

offense, [the defendant] causes the death of

any person." A.R.S. § 13-1105(A)(2).

The

capital punishment statute provided that

defendant's expectation of the receipt of

something of pecuniary value was an

aggravating factor. A.R.S. § 13-703(F)(5).

So, unless the Arizona Supreme Court had

narrowed the clear terms of the statutes to

a robber's benefit prior to the LaGrands'

commission of the murder, there was no due

process violation.

The cases

cited by the LaGrands do not support the

result they seek. Two of them, State v.

Jordan, 126 Ariz. 283, 614 P.2d 825 (in banc

), cert. denied, 449 U.S. 986, 101 S.Ct.

408, 66 L.Ed.2d 251 (1980), and State v.

Jeffers, 135 Ariz. 404, 661 P.2d 1105 (in

banc ), cert. denied, 464 U.S. 865, 104 S.Ct.

199, 78 L.Ed.2d 174 (1983), did not involve

reliance on the pecuniary gain factor.

Nor do the

other cases cited support their argument.

State v. Correll, 148 Ariz. 468, 479, 715

P.2d 721, 732 (1986) (in banc ), involved

murders committed in order to insure that no

one be left to identify the robbers ("The

only motivation for the killings was to

leave no witnesses to the robbery."). State

v. Hensley, 142 Ariz. 598, 604, 691 P.2d

689, 695 (1984) (in banc ), was much the

same ("In this case, the murders were a part

of the overall scheme of the robbery with

the specific purpose to facilitate the

robbers' escape.").

There is

language in Hensley from an earlier case

indicating that "an unexpected or accidental

death that was not in furtherance of the

defendant's goal of pecuniary gain" would

not support a finding of the aggravating

circumstance. Id. 142 Ariz. at 603, 691 P.2d

at 694 (quoting State v. Harding, 137 Ariz.

278, 296, 670 P.2d 383, 401 (1983) (Gordon,

J., concurring), cert. denied, 465 U.S.

1013, 104 S.Ct. 1017, 79 L.Ed.2d 246

(1984)).2

The

LaGrands' argument seems to be premised on

their claim that the killing was not in

furtherance of the robbery, but rather came

about when Ken Hartsock kicked Karl during a

struggle, and Karl impulsively reacted by

stabbing him. However, this argument is

contrary to Dawn Lopez's testimony that she

saw both men involved in a struggle with Ken

Hartsock and her testimony that she twice

heard at least one of them say "make sure

he's dead."

Ms.

Lopez's evidence is consistent with a murder

committed in order to eliminate witnesses.

The LaGrands' argument is also contrary to

the Enmund3

finding of the district court: "The court

finds beyond a reasonable doubt that both

defendants participated in the actual

killing of Mr. Hartsock and that both

defendants intended to kill him."

The

Arizona Supreme Court's decisions in the

LaGrand cases were not an unforeseeable

departure from its existing jurisprudence,

and no due process violation occurred.

Poland v. Stewart, 117 F.3d 1094, 1098-1100

(9th Cir.1997).

The

LaGrands contend that, as German nationals,

they were entitled to contact the German

consulate upon being arrested and that the

Arizona authorities' failure to inform them

of this right violated their constitutional

rights. The Vienna Convention on Consular

Relations of 1963, Article 36, TIAS 6820, 21

U.S.T. 77,596 UNTS 261 (Ratified by United

States Senate on December 24, 1969) ("The

Treaty"), requires the receiving state (here,

the United States) to allow nationals of the

sending state (here, Germany) to notify

their national consulate after they are

arrested. The authorities of the receiving

state are required to inform the arrested

foreign national "without delay of his

rights under this sub-paragraph." Id.

It is

undisputed that the State of Arizona did not

notify the LaGrands of their rights under

the Treaty. It is also undisputed that this

claim was not raised in any state proceeding.

The claim is thus procedurally defaulted.

We may

address the merits of a procedurally

defaulted claim if the petitioner can show

cause for the procedural default and actual

prejudice as a result of the alleged

violations of federal law. Bonin v. Calderon,

77 F.3d 1155, 1158 (9th Cir.), cert. denied,

516 U.S. 1143, 116 S.Ct. 980, 133 L.Ed.2d

899 (1996).

To

demonstrate cause, the petitioner must show

the existence of "some objective factor

external to the defense [which] impeded

counsel's efforts to comply with the State's

procedural rule." Murray v. Carrier, 477

U.S. 478, 488, 106 S.Ct. 2639, 2645, 91 L.Ed.2d

397 (1986); see also McCleskey v. Zant, 499

U.S. 467, 497, 111 S.Ct. 1454, 1471-72, 113

L.Ed.2d 517, reh'g denied, 501 U.S. 1224,

111 S.Ct. 2841, 115 L.Ed.2d 1010 (1991)

(cause is external impediment such as

government interference or reasonable

unavailability of claim's factual basis).

Lacking cause and prejudice, we may

nonetheless consider procedurally barred

claims if failure to do so would result in

the conviction or execution of " 'one who is

actually innocent.' " Schlup v. Delo, 513

U.S. 298, 321, 115 S.Ct. 851, 864, 130 L.Ed.2d

808 (1995).

As to

cause, the LaGrands argue ineffective

assistance of counsel. In Karl's case, he

was represented by one lawyer at trial, a

second lawyer on appeal, a third lawyer in

his state post-conviction relief (PCR)

proceeding and present counsel on his

federal habeas. Karl has offered no support

for his argument that something external to

the defense prevented his lawyer from

presenting this claim to the state courts,

except ineffective assistance of trial

counsel. He has not, however, argued, let

alone shown, that any external factor

prevented his counsel in the state PCR

proceeding from presenting this claim. He

has therefore not shown cause.

Walter,

who has had the same lawyer throughout,

signed a waiver of his right to present

ineffective assistance of counsel claims. We

will discuss this waiver in more detail when

we reach Walter's individual claims. The

waiver is sufficient to preclude using his

lawyer's ineffective assistance as cause for

failing to present this claim to the state

courts. Thus, the LaGrands have failed to

demonstrate cause for their procedural

defaults in state court.

The

LaGrands argue that they meet the

fundamental miscarriage of justice standard

since they are actually innocent of the

death penalty. Their basic argument is that

the failure to notify them of their right to

contact the German consulate "effectively

blocked LaGrands' ability to gather

exculpatory or mitigating evidence." The

Supreme Court has stated, however, that

actual innocence of the death penalty must

focus on eligibility for the death penalty,

and not on additional mitigation. Sawyer v.

Whitley, 505 U.S. 333, 345-46, 112 S.Ct.

2514, 2523, 120 L.Ed.2d 269 (1992).

The

evidence the LaGrands contend they were

blocked from obtaining relates to background

information concerning their abusive

childhoods in Germany and the difficulties

that children of mixed marriages encountered

in Germany. While this evidence could have

related to mitigation, it has no

demonstrable connection to the findings of

pecuniary gain or that the murder was

committed in an especially cruel, heinous or

depraved manner. Because the postulated

evidence does not go to eligibility for the

death penalty, the LaGrands do not

substantiate their claim of actual innocence.

C. The

Constitutionality of Arizona's Felony Murder

Statute

The

LaGrands requested a second-degree murder

instruction as a lesser-included offense to

the felony murder charge. The trial court

denied the request as Arizona felony murder

law does not include any lesser-included

offenses. State v. LaGrand, 153 Ariz. at

30-31, 734 P.2d at 572-73. The LaGrands

challenge the court's refusal to give the

lesser-included instruction on the basis

that the ruling was contrary to the teaching

of Beck v. Alabama, 447 U.S. 625, 100 S.Ct.

2382, 65 L.Ed.2d 392 (1980), and thus

violated the Constitution.

In Beck,

the Supreme Court considered a unique

Alabama statute under which the jury was

given only a choice of conviction of capital

murder or acquittal. The Supreme Court

reversed Beck's conviction on the basis that

the limited choices available to the jury

impermissibly enhanced "the risk of an

unwarranted conviction." Id. at 637, 100

S.Ct. at 2389. "The goal of the Beck rule

... is to eliminate the distortion of the

factfinding process that is created when the

jury is forced into an all-or-nothing choice

between capital murder and innocence." Schad

v. Arizona, 501 U.S. 624, 646-47, 111 S.Ct.

2491, 2505, 115 L.Ed.2d 555 (1991).

In the

instant case, however, the all-or-nothing

scenario condemned in Beck did not exist. As

to the charge of murder in count one, the

jury was told it could return verdicts of

guilty of murder in the first degree, murder

in the second degree or not guilty. The

LaGrands were charged with first-degree

murder.

The jury

was told that the crime could be committed

as a felony murder or as premeditated murder.

An instruction on second-degree murder was

given, as was a possible verdict of second-degree

murder as to Count One. The jury was not

specifically told that second-degree murder

was not a lesser-included offense to felony

murder, although a close reading of the

instructions could have led the jury to that

conclusion.

The jury

was also given the choice of convicting or

acquitting the defendants of attempted first-degree

murder, attempted second-degree murder,

aggravated assault, armed robbery, robbery

and kidnapping in the other counts. In the

event the jury had found itself unable to

agree on a conviction of first-degree murder,

it would not have had to face the choice of

simply acquitting the LaGrands.

Thus, the

instructions in the instant case do not

implicate the concerns of the Beck doctrine

because the LaGrands' jury was not faced

with the "all or nothing" choice presented

in Beck. See Schad, 501 U.S. at 646-47, 111

S.Ct. at 2505 (no Beck error where

instruction does not present jury with "all-or-nothing

choice between the offense of conviction

(capital murder) and innocence") (quotations

omitted).

The

LaGrands argue that the state courts did not

adequately consider the mitigation evidence

presented at the sentencing. They rely on

the panel opinion in Jeffers v. Lewis, 974

F.2d 1075, 1079 (9th Cir.1992): "[when]

there is a risk that mitigating evidence in

[a] case was not fully considered, [Petitioner's]

sentence of death cannot stand."

However,

this court took the Jeffers case en banc,

and affirmed the district court's denial of

the petition. Jeffers v. Lewis, 38 F.3d 411

(9th Cir.1994), cert. denied, 514 U.S. 1071,

115 S.Ct. 1709, 131 L.Ed.2d 570 (1995).

There we said, quoting Jeffries v. Blodgett,

5 F.3d 1180, 1197 (9th Cir.1993), cert.

denied, 510 U.S. 1191, 114 S.Ct. 1294, 127

L.Ed.2d 647 (1994): "[D]ue process does not

require that the sentencer exhaustively

document its analysis of each mitigating

factor as long as a reviewing federal court

can discern from the record that the state

court did indeed consider all mitigating

evidence offered by the defendant." Jeffers,

38 F.3d at 418.

The

LaGrands do not argue that the state courts

refused to consider any of their proffered

mitigating evidence. They argue that the

mitigating circumstances were not considered

"fully." However, the federal courts do not

review the imposition of the sentence de

novo. Here, as in the state courts' finding

of the existence of an aggravating factor,

we must use the rational fact-finder test of

Lewis v. Jeffers. That is, considering the

aggravating and mitigating circumstances,

could a rational fact-finder have imposed

the death penalty? The answer is "yes."

The

aggravating circumstances of pecuniary gain,

a murder committed in an especially heinous,

cruel or depraved manner and prior

conviction of a felony involving the use or

threat of violence were well supported in

the record. While there were mitigating

factors, such as the LaGrands' ages (Walter

was 19; Karl, 18), their prior home life and

their remorse, a rational sentencer could

have nevertheless imposed the death penalty.

E.

District Court's Upholding of Death Penalty

The

LaGrands argue that the death penalty should

not have been upheld by the district court.

They point out that the Supreme Court has

said that "the death penalty can be upheld

in only the most egregious cases," citing

Godfrey v. Georgia, 446 U.S. 420, 427, 100

S.Ct. 1759, 1764, 64 L.Ed.2d 398 (1980), and

that the death penalty "is reserved for

truly exceptional cases," citing State v.

Bible, 175 Ariz. 549, 606, 858 P.2d 1152,

1209 (1993). They argue that this case does

not come within the "truly exceptional"

category.

The

LaGrands in effect ask us to review the

Arizona Supreme Court's determination that

the imposition of the death penalty in their

case was not disproportionate to the penalty

imposed in similar cases. See State v.

Walter LaGrand, 153 Ariz. at 37, 734 P.2d at

579; State v. Karl LaGrand, 152 Ariz. at

488-90, 733 P.2d at 1072-73.

However,

once the Arizona Supreme Court "undertook

its proportionality review in good faith and

found that [the LaGrands'] sentence was

proportional to the sentences imposed" in

similar cases, "[t]he Constitution does not

require [the federal habeas court] to look

behind that conclusion." Lewis v. Jeffers,

497 U.S. 764, 779, 110 S.Ct. 3092, 3101, 111

L.Ed.2d 606 (1990) (quoting Walton v.

Arizona, 497 U.S. 639, 655-56, 110 S.Ct.

3047, 3058, 111 L.Ed.2d 511 (1990)). There

is no indication that the Arizona Supreme

Court's proportionality review was conducted

in bad faith. The LaGrands' proportionality

claim therefore fails.

The

LaGrands also contend that the state courts

and the federal district court improperly "assumed"

the existence of the aggravating factor of

"cruel, heinous or depraved," rather than

finding its existence beyond a reasonable

doubt. However, the state courts did indeed

premise their finding of "cruel, heinous or

depraved" upon specific evidence of

Hartsock's physical and mental suffering,

the LaGrands' infliction of gratuitous

violence upon and mutilation of Hartsock,

and Hartsock's position of helplessness. See

State v. Walter LaGrand, 153 Ariz. at 36-37,

734 P.2d at 578-79. The state trial court

found that this aggravating circumstance had

been established beyond a reasonable doubt.

See id. at 34, 734 P.2d at 576. Accordingly,

this claim also fails.

In

Arizona, all condemned prisoners will be

executed by means of lethal injection unless

those who were sentenced before the Arizona

legislature adopted lethal injection

affirmatively choose lethal gas as the

method to be used in their cases. A.R.S. §

13-704(B). The LaGrands come within the

group having this option under state law.

Thus, they would be executed by lethal gas

only if they affirmatively choose to do so.

The court

held in Poland v. Stewart, 117 F.3d 1094,

1104 (9th Cir.1997), that Poland's claim

that lethal gas was an unconstitutional

method of execution was not ripe. For the

same reasons, the LaGrands' claim is not

ripe and cannot be considered. Id.

G.

Lethal Injection as a Method of Execution

The

LaGrands also contend that lethal injection

is an unconstitutional method of execution.4

In support of this claim, they submitted the

reports of eyewitnesses to two Arizona

executions using lethal injection. One

report, published in the Arizona Republic on

March 3, 1993, said that John George Brewer

"was pronounced dead at 12:18 a.m., one

minute after he received a combination of

three drugs injected through a pair of

intravenous tubes."

A report

of the execution of James Dean Clark was

published in the same paper on April 15,

1993, but with a different by-line. The

report said:

Then as three lethal

drugs surged into his veins at 12:05 a.m.,

Clark's chest heaved several times, and his

skin turned ashen.... Because it didn't look

like he simply was going to sleep, Clark's

execution was much more gruesome, intense,

bizarre and dramatic than I had anticipated.

But it was also much easier to watch than I

expected, because Clark didn't appear to

suffer nearly as much as Don Eugene Harding,

who died in the gas chamber last April.

The

LaGrands also submitted an affidavit from an

observer of the lethal gas execution of Don

Harding:

Don

Harding took ten minutes and thirty-one

seconds to die. At least eight of those

minutes were spent in gross and brutal agony....

Then I will never forget the look on his

face when he turned to me several seconds

after first having inhaled the fumes. It is

an image of atrocity that will haunt me for

the rest of my life. Don Harding's death was

slow, painful, degrading and inhumane.... He

literally choked and convulsed to death in

front of my eyes.

In

addition to the reports mentioned above, the

LaGrands submitted the affidavit of one

Michael L. Radelet, prepared for a separate

capital case in Arizona. Radelet, a

sociologist who collected reports of "botched"

executions, described what happened in nine

executions by lethal injection. They

involved either problems in finding a

suitable vein or violent reactions to the

drugs. None took place in Arizona and none

were tied to the protocol used in Arizona.

The

LaGrands also submitted the affidavit of a

doctor on the staff of the College of

Medicine at the University of Arizona who

reviewed the procedures established for the

administration of lethal injection in

Arizona. Apparently he did not witness

either of the two executions in Arizona by

lethal injection. His ultimate conclusion

was that the procedures were flawed, but his

affidavit is replete with speculation.

For

example, he states at some length the

possible consequences of administering the

designated drugs in the wrong sequence.

While he states that there may be some risk

of this, the two Arizona executions

recounted in the other materials show no

such problems in actual practice. See

Campbell v. Wood, 18 F.3d 662, 668 (9th

Cir.) ("The risk of accident cannot and need

not be eliminated from the execution process

in order to survive constitutional review."),

cert. denied, 511 U.S. 1119, 114 S.Ct. 2125,

128 L.Ed.2d 682 (1994).

The

LaGrands' challenge is similar to that

rejected in Poland, 117 F.3d at 1104-05, and

the district court did not err in rejecting

their challenge to Arizona's use of lethal

injection as a method of execution.

WALTER'S INDIVIDUAL

CLAIMS

Karl made

two separate recorded statements in the late

hours of January 7 and early hours of

January 8. In those statements he assumed

sole responsibility for the attack on Ken

Hartsock, saying it occurred after Mr.

Hartsock kicked him in the leg. He said that

Walter did not stab anyone and that Walter

was not in the room when he stabbed Mr.

Hartsock and Ms. Lopez.

Pursuant

to the stipulation of the parties, the trial

court ruled that the confessions were

voluntary but that they were taken in

violation of Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S.

436, 86 S.Ct. 1602, 16 L.Ed.2d 694 (1966).

This precluded the State from introducing

the confessions as evidence in the guilt

phase of the trial against Karl. The Miranda

stipulation did not, however, preclude

Walter from introducing the confessions as

part of his defense. Walter thus sought to

have the confessions introduced under

Arizona Rule of Evidence 804(b)(3), which is

identical to Federal Rule of Evidence

804(b)(3). The rule provides as follows:

Rule 804. Hearsay

Exceptions; Declarant Unavailable

(b)

Hearsay exceptions. The following are not

excluded by the hearsay rule if the

declarant is unavailable as a witness:

(b)(3)

Statement against interest. A statement

which was at the time of its making so far

contrary to the declarant's pecuniary or

proprietary interest, or so far tended to

subject him to civil or criminal liability

... that a reasonable man in his position

would not have made the statement unless he

believed it to be true. A statement tending

to expose the declarant to criminal

liability and offered to exculpate the

accused is not admissible unless

corroborating circumstances clearly indicate

the trustworthiness of the statement.

153 Ariz.

at 26-27, 734 P.2d at 568-69 (quoting A.R.S.

Rule of Evid. 804(b)(3)). After considering

Walter's request on four separate occasions,

the trial court held the confessions were

inadmissible at the guilt phase of the trial.

On appeal

from the LaGrands' convictions, the Arizona

Supreme Court explained the proper method of

determining admissibility under Rule

804(b)(3):

We therefore hold that a

judge's inquiry, made to assure himself that

the corroboration requirement of Rule

804(b)(3) has been satisfied, should be

limited to asking whether evidence in the

record corroborating and contradicting the

declarant's statement would permit a

reasonable person to believe that the

statement could be true. If a judge believes

that a reasonable person could [so] conclude

... then the judge must admit the statement

into evidence.

State v.

Walter LaGrand, 153 Ariz. at 36, 734 P.2d at

570.

Applying

this standard, the Arizona Supreme Court

concluded that the trial court's refusal to

admit the statements was not in error:

Evidence

both corroborating and contradicting Karl's

statements exists. The following evidence

corroborated Karl's statements: Karl did

have a bruise on his leg as he stated; Lopez

testified that she saw Hartsock kick someone;

Lopez testified that only one person stabbed

her; and Walter testified that he was out of

the room when the stabbings occurred.

The

following evidence contradicted Karl's

statements: Lopez testified that she saw

Hartsock struggling with two men; Lopez

testified that she was "positive" that

Walter had stabbed her; Lopez testified that

after being stabbed by Walter and falling to

the floor one brother said to the other

twice, "Just make sure he's dead"; and the

forensic consultant who performed an autopsy

on Hartsock testified that more than one

instrument was used to inflict Hartsock's

wounds.

After

reviewing the above corroborating and

contradicting evidence, we do not think that

a reasonable person could conclude from the

same corroborating and contradictory

evidence that Karl's exculpatory statements

could be true. The trial judge properly

denied admission of Karl's statements.

Id. 153

Ariz. at 29, 734 P.2d at 571.

Walter's

argument here is that exclusion of the

confessions violated his Sixth Amendment

right to "present a complete defense" to the

charges against him. California v. Trombetta,

467 U.S. 479, 485, 104 S.Ct. 2528, 2532, 81

L.Ed.2d 413 (1984). He relies on "the

Chambers doctrine" derived from Chambers v.

Mississippi, 410 U.S. 284, 93 S.Ct. 1038, 35

L.Ed.2d 297 (1973).

Chambers

was convicted of killing a policeman in a

small town in Mississippi. Gable McDonald

had confessed to killing the officer in a

statement to Chambers' lawyer, but he later

repudiated the confession.

At trial,

Chambers attempted to show he did not shoot

the officer. He also tried to show that

McDonald was the shooter. The trial court

would not permit Chambers to introduce the

testimony of three witnesses to whom

McDonald had admitted shooting the officer

on the grounds that the proffered testimony

was hearsay. Mississippi recognized

statements against pecuniary interest, but

not statements against penal interest, as an

exception to the hearsay rule.

The Court

reversed Chambers' conviction, saying:

The testimony rejected by

the trial court here bore persuasive

assurances of trustworthiness and thus was

well within the basic rationale of the

exception for declarations against interest.

That testimony also was critical to

Chambers' defense. In these circumstances,

where constitutional rights directly

affecting the ascertainment of guilt are

implicated, the hearsay rule may not be

applied mechanistically to defeat the ends

of justice.

Chambers,

410 U.S. at 302, 93 S.Ct. at 1049.

Chambers

is but one of several Supreme Court

decisions dealing with state rules of

evidence used to reject a defendant's

evidence on "mechanistic" grounds. In Green

v. Georgia, 442 U.S. 95, 99 S.Ct. 2150, 60

L.Ed.2d 738 (1979), the Court again reversed

a conviction where the Georgia courts had

rejected hearsay statements on the ground

that Georgia did not recognize the penal

interest exception to the hearsay rule.

An earlier

case, Washington v. Texas, 388 U.S. 14, 87

S.Ct. 1920, 18 L.Ed.2d 1019 (1967), involved

Texas statutes which prohibited persons

charged or convicted as co-participants in a

crime from testifying for each other, though

they could testify for the State.

Washington's proffer of testimony tended to

show that Washington was not the shooter.

The evidence was rejected pursuant to the

Texas statutes. The Supreme Court reversed

the conviction on the grounds that the

State's rule "arbitrarily" deprived

Washington of his right under the Sixth

Amendment to present witnesses in his

defense.

In the

more recent case of Rock v. Arkansas, 483

U.S. 44, 107 S.Ct. 2704, 97 L.Ed.2d 37

(1987), the Court held that a state could

not "arbitrarily or disproportionately"

prevent a defendant from testifying in her

defense by implementing a per se rule

prohibiting hypnotically enhanced testimony.

These

cases, taken together, stand for the

proposition that states may not impede a

defendant's right to put on a defense by

imposing mechanistic (Chambers ) or

arbitrary (Washington and Rock ) rules of

evidence. But they do not stand for the

proposition that a defendant must be allowed

to put on any evidence he chooses. As the

Court said in Chambers:

Few rights

are more fundamental than that of an accused

to present witnesses in his own defense. In

the exercise of this right, the accused, as

is required of the State, must comply with

established rules of procedure and evidence

designed to assure both fairness and

reliability in the ascertainment of guilt

and innocence.

410 U.S.

at 302, 93 S.Ct. at 1049 (citations omitted).

See also Crane v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 683,

690, 106 S.Ct. 2142, 2146, 90 L.Ed.2d 636

(1986) ("[W]e have never questioned the

power of States to exclude evidence through

the application of evidentiary rules that

themselves serve the interests of fairness

and reliability-even if the defendant would

prefer to see the evidence admitted.").5

Here, Karl

LaGrand's confession was not excluded as a

result of rigid application of arbitrary or

mechanistic rules of admissibility. Rather,

the state courts determined, after analyzing

the proffer and the corroborating and

contradictory circumstances, that the

confession was not sufficiently reliable to

warrant its introduction. Thus, the refusal

to admit Karl's confession did not run afoul

of the Chambers-Washington-Rock prohibition

against arbitrary and mechanistic exclusion

of exculpatory evidence.

While

Chambers clearly prohibits states from

excluding exculpatory evidence by

application of rigid or arbitrary

exclusionary rules, it is not clear whether

the Chambers doctrine implies a requirement

of independent federal review of a state

court's determination of reliability. In Lee

v. McCaughtry, 933 F.2d 536, 538 (7th Cir.),

cert. denied, 502 U.S. 895, 112 S.Ct. 265,

116 L.Ed.2d 218 (1991), the Seventh Circuit

suggested that Chambers imposed no such

requirement: "Once a state has brought its

rules of evidence into line with

constitutional norms, there is little point

in case-by-case federal review of

evidentiary rulings."

However,

the Lee court specifically declined to

answer the question whether federal review

is required, and instead duplicated the

state court's reliability inquiry and

concluded that the refusal to admit the

evidence was proper. Id. See also Turpin v.

Kassulke, 26 F.3d 1392, 1397 (6th Cir.1994)

(reversing district court's granting of

habeas petition after reviewing the

testimony excluded by the state trial court

and concluding that the evidence was indeed

"fundamentally untrustworthy"), cert. denied,

513 U.S. 1118, 115 S.Ct. 916, 130 L.Ed.2d

797 (1995).

We need

not answer the question here because, even

assuming that federal review is required,

the Arizona Supreme Court's conclusion-that

Karl's statement exculpating Walter was not

sufficiently reliable to come in under Rule

804(b)(3)-finds ample support in the record

and thus cannot be said to have had "substantial

and injurious effect or influence in

determining the jury's verdict" against

Walter LaGrand. Brecht v. Abrahamson, 507

U.S. 619, 623, 113 S.Ct. 1710, 1716, 123

L.Ed.2d 353 (1993) (quoting Kotteakos v.

United States, 328 U.S. 750, 776, 66 S.Ct.

1239, 1253, 90 L.Ed. 1557 (1946)).6

Karl

LaGrand's confession included two separate

statements: first, that he, Karl LaGrand,

stabbed Ken Hartsock, and second, that

Walter LaGrand did not stab anyone. Because

the "statements against penal interest"

exception to the hearsay rule is premised

upon the inherent reliability of statements

that tend to incriminate the declarant,

federal courts have concluded that a

statement that includes both incriminating

declarations and corollary declarations that,

taken alone, are not inculpatory of the

declarant, must be separated and only that

portion that is actually incriminating of

the declarant admitted under the exception.

See Williamson v. United States, 512 U.S.

594, 599-600, 114 S.Ct. 2431, 2434-35, 129

L.Ed.2d 476 (1994) (noting that judges in

federal cases must separate the

incriminatory portions of statements from

other portions for purposes of Rule

804(b)(3) because "[t]he fact that a person

is making a broadly self-inculpatory

confession does not make more credible the

confession's non-self-inculpatory parts");

Carson v. Peters, 42 F.3d 384, 386 (7th

Cir.1994) ("Portions of inculpatory

statements that pose no risk to the

declarants are not particularly reliable;

they are just garden variety hearsay.");

United States v. Porter, 881 F.2d 878,

882-83 (10th Cir.) (if a statement

exculpatory to the accused is severable from

the statement inculpatory to the declarant,

each statement must be separately analyzed

under Rule 804(b)(3)), cert. denied, 493

U.S. 944, 110 S.Ct. 348, 107 L.Ed.2d 336

(1989); United States v. Lilley, 581 F.2d

182, 188 (8th Cir.1978) ("To the extent that

a statement is not against the declarant's

interest, the guaranty of trustworthiness

does not exist and that portion of the

statement should be excluded.").

In stating

that Walter did not stab anyone, Karl was

not further incriminating himself. The

reliability that attends the inculpatory

part of his confession does not afford any

reliability to that part of the statement

that merely exculpates Walter. Accordingly,

it was not entitled to the benefit of Rule

804(b)(3)'s exception to the hearsay rule.

Further,

as noted by the Arizona Supreme Court,

direct evidence contradicted Karl's

statement that Walter was not involved in

the stabbing of Ken Hartsock: Mr. Hartsock

was stabbed 24 times and all wounds were

frontal; the wounds were consistent with two

different instruments having been used; Ms.

Lopez, the only eyewitness, testified that

Walter was standing in front of Mr. Hartsock

while Karl held him from behind; that at

least one person said twice, "Make sure he's

dead"; and that Walter stabbed her.

Finally,

under federal case law, a judge ruling on

the reliability of Karl's statement could

consider that Walter's own testimony was not

corroborative, see Turpin, 26 F.3d at

1397-98, and that the exculpatory statements

of family members are not considered to be

highly reliable, United States v. Bobo, 994

F.2d 524, 528 (8th Cir.), cert. denied, 510

U.S. 891, 114 S.Ct. 250, 126 L.Ed.2d 203

(1993).

In light

of the foregoing, we conclude that even if

Chambers requires federal review of the

state courts' determination of reliability,

the Arizona courts' conclusion that the

statement was not sufficiently reliable to

be admitted was both "reasoned and

reasonable" and, as such, did not violate

Walter LaGrand's right to present a complete

defense. Carson, 42 F.3d at 387.

Walter

also argues that the standard of "clearly"

indicating a statement's trustworthiness is

"too onerous a burden." He argues that

Chambers stands for the proposition that the

courts can require only a "more reasonable,

minimal [burden]." He relies mainly on texts

and law review articles,7

being unable to point to cases which

specifically hold that Rule 804(b)(3), in

either state or federal garb, runs afoul of

a defendant's due process rights for that

reason. This argument fails because, given

the inherent unreliability of corollary

exculpatory statements, Rule 804(b)(3)'s

requirement that such statements be clearly

corroborated is entirely legitimate and

reasonable.

Walter

also makes a related argument concerning the

discriminatory effects of the corroboration

requirement of Rule 804(b)(3). This argument

springs from the Supreme Court's statement

in Ohio v. Roberts, 448 U.S. 56, 100 S.Ct.

2531, 65 L.Ed.2d 597 (1980), that the

Confrontation Clause does not bar

introduction of hearsay testimony which

bears sufficient indicia of reliability. The

Court said that reliability can be inferred

without further corroboration in cases where

the evidence falls within a "firmly rooted

hearsay exception." Id. at 66, 100 S.Ct. at

2539. Otherwise, a "showing of

particularized guarantees of trustworthiness

[would] be required." Id.

Since the

state can introduce a confession without

showing clear corroboration, the argument

goes, the defendant should be able to do the

same. This argument suffers from the same

flaw as the preceding one: exculpatory

statements such as Karl's do not come within

a "firmly rooted hearsay exception" as do

incriminating statements. See Carson v.

Peters, 42 F.3d at 386. In limiting

admissible evidence to that found to be

reliable, the rule-writers may legitimately

impose the burden of offering proof of

clearly corroborating circumstances on those

offering exculpatory hearsay statements.

Walter

also argues that the state courts' rejection

of Karl's confessions unconstitutionally

interfered with the jury's fact-finding

role. The state's contention that this claim

was not raised in the district court or in

state court has merit. In the district court,

the argument that the trial court's ruling

invaded the province of the jury was simply

a subset of the contention that Chambers

required the trial court to admit the

evidence. There was not, as there is here, a

stand-alone argument of interference with

the jury's function. A decision on this

issue is subsumed in the ruling on the

"Chambers doctrine" and need not be

separately addressed.

We

conclude that there was no constitutional

error in the Arizona courts' decision to

exclude under Rule 804(b)(3) Karl LaGrand's

statement that Walter was not involved in

the stabbing of Ken Hartsock.

Walter

LaGrand has been represented by Bruce Burke,

a Tucson lawyer, throughout all proceedings

to date. Prior to appointing him as counsel

in Walter's federal habeas proceeding, the

district court required Mr. Burke to discuss

possible claims of ineffective assistance of

counsel with Walter and then to file a

status report with the court.

In the

status report, Mr. Burke recounted a meeting

he had had with Walter in which he had

explained the issue of ineffective

assistance of counsel, "and [had told him]

that such a claim might provide him with an

avenue for relief from the death penalty."

Mr. Burke also informed Walter that he knew

of no instances in which his own assistance

had been ineffective.

He further

told Walter that the court "would appoint an

additional attorney, or a new attorney, to

examine my performance" if Walter desired.

Walter told Mr. Burke that "he did not want

me to take steps which might require me to

withdraw as his attorney of record and he

did not wish me to seek appointment of a new

attorney to consider the issue."

After Mr.

Burke was appointed in federal court, he

learned that Karl's counsel was going to

present evidence to the effect that his

trial counsel had been ineffective at the

sentencing phase of the case. Because Mr.

Burke believed that this drew into question

his own effectiveness at sentencing, he

moved to withdraw as Walter's counsel.

The

district court denied the motion on the

grounds that Walter had been given an

opportunity to change counsel in order to

present an ineffective assistance of counsel

claim but had waived that right. The court

also held that no prejudice had been shown

since the claimed failure did not constitute

ineffective assistance of counsel.

We review

the district court's order for abuse of

discretion. United States v. Baker, 10 F.3d

1374 (9th Cir.1993), cert. denied, 513 U.S.

934, 115 S.Ct. 330, 130 L.Ed.2d 289 (1994).

Walter's waiver was not of specific

instances of ineffectiveness, but of the

employment of new counsel to potentially

pursue such claims.

In this instance, Walter's

claim that the waiver was not effective

because he didn't know the facts

constituting the claim has no merit. When

Walter waived the offer of new counsel, he

was waiving the benefits of new

representation, among which would

potentially have been the presentation of

this sort of new claim. See United States v.

Lowry, 971 F.2d 55 (7th Cir.1992). Since the

claim now asserted was well within the

waiver, the district court did not abuse its

discretion in denying the motion.

For the

foregoing reasons, we affirm the district

court's denial of Walter's petition.

A claim of

ineffective assistance of counsel presents a

mixed question of law and fact which we

review de novo. Sanders v. Ratelle, 21 F.3d

1446, 1451 (9th Cir.1994) (citing Strickland

v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 698, 104 S.Ct.

2052, 2069, 80 L.Ed.2d 674 (1984)).

Under

Strickland, a petitioner seeking habeas

relief based on the ineffective assistance

of counsel must show: (1) that the counsel's

performance falls "below an objective

standard of reasonableness," 466 U.S. at

688, 104 S.Ct. at 2064; and (2) that there

is a reasonable probability that, but for

counsel's errors, the result of the

proceeding would have been different, id. at

694, 104 S.Ct. at 2068.

Karl

claims that the district court erred on his

Strickland ineffectiveness claim: (1) by

limiting the scope of the evidentiary

hearing; and (2) by finding that Karl's

trial counsel's performance did not fall

below an objective standard of

reasonableness.

In a

capital case, a petitioner is entitled to an

evidentiary hearing where there has been no

state court evidentiary hearing and the

petitioner raises a "colorable" claim of

ineffective assistance. Smith v. McCormick,

914 F.2d 1153, 1170 (9th Cir.1990). The

scope of an evidentiary hearing on a motion

under 28 U.S.C. § 2254 is committed to the

discretion of the district court. United

States v. Layton, 855 F.2d 1388, 1421 (9th

Cir.1988), cert. denied, 489 U.S. 1046, 109

S.Ct. 1178, 103 L.Ed.2d 244 (1989).

In the

present case, the district court held an

evidentiary hearing on Karl's ineffective

assistance of counsel claim for the limited

purpose of determining whether Karl could

establish the first prong of the Strickland

test. Karl was therefore required to prove

that his counsel's performance was deficient

before the court would entertain evidence

regarding prejudice.

Karl

argues that the district court's limitation

on the scope of the evidentiary hearing was

erroneous for two reasons. First, Karl

claims that the two prongs of the Strickland

test are interconnected and that they must

be considered together.

No court

has ever held that both prongs of the

Strickland test must be examined

simultaneously. To the contrary, the Supreme

Court has held that a court is not required

to address both components of the Strickland

test in deciding an ineffective assistance

of counsel claim "if the defendant makes an

insufficient showing on one." Strickland,

466 U.S. at 697, 104 S.Ct. at 2069.

Thus, a

court need not determine whether defendant

was prejudiced by counsel's alleged

deficiencies if it determines that counsel's

performance was not deficient. See id.;

Cacoperdo v. Demosthenes, 37 F.3d 504, 508

(9th Cir.1994) (defendant failed to show

lack of thorough investigation of law and

facts and therefore failed to meet his

burden on the first prong of the Strickland

test), cert. denied, 514 U.S. 1026, 115 S.Ct.

1378, 131 L.Ed.2d 232 (1995).

Second,

Karl claims that the district court erred in

not allowing him to present expert medical

and legal testimony regarding his trial

counsel's performance. Karl alleges that he

needed to present expert testimony to show

what evidence could and should have been

presented by his trial counsel. This claim

lacks merit.

The

district court allowed Karl to present the

testimony of five attorneys regarding the

standard of care used by Karl's attorney.

These attorneys were all familiar with the

case. Karl has failed to cite any authority,

and we have found none, that supports his

contention that only outside expert

testimony can provide a basis on which to

measure counsel's performance.

Furthermore, the majority of the proffered

expert testimony rejected by the court went

to the second prong of the Strickland test,

which was not the subject of the hearing.

Thus, the district court's refusal to allow

the expert testimony based on its finding

that the testimony would not be relevant to

the limited scope of the evidentiary hearing

was reasonable.8

See Wade v. Calderon, 29 F.3d 1312, 1326-27

(9th Cir.1994) (upholding district court's

limitation of defendant's expert evidence

where the limitation was "reasonably

designed to restrict the issue to competence

of counsel, on the basis of what was

reasonably known by counsel at the time of

trial"), cert. denied, 513 U.S. 1120, 115

S.Ct. 923, 130 L.Ed.2d 802 (1995).

Because a

defendant is required to prove both prongs

of the Strickland test before relief can be

granted, the district court did not abuse

its discretion in limiting the scope of the

evidentiary hearing to determine whether

defendant met the first prong of the

Strickland test. See Layton, 855 F.2d at

1421.

Furthermore, the district court's limitation

of Karl's expert evidence was reasonably

designed to restrict the issue of the

hearing to the first prong of the Strickland

test. Therefore, the district court did not

abuse its discretion in refusing the expert

medical and legal testimony proffered by

Karl. See Wade, 29 F.3d at 1326-27.

The United States

Constitution guarantees that criminal

defendants "shall enjoy the right to have

the assistance of counsel for [their]

defense." U.S. Const. amend VI. This

constitutional right to counsel means that

all defendants have the right to effective

counsel. McMann v. Richardson, 397 U.S. 759,

771 n. 14, 90 S.Ct. 1441, 1449 n. 14, 25

L.Ed.2d 763 (1970).

To

establish that he was deprived of his right

to the effective assistance of counsel, a

defendant must show that his counsel's

performance falls "below an objective

standard of reasonableness." Strickland, 466

U.S. at 688, 104 S.Ct. at 2064. This inquiry

must focus on "whether counsel's assistance

was reasonable considering all the

circumstances." Id. at 688, 104 S.Ct. at

2065.

Prevailing norms of

practice ... are guides to determining what

is reasonable, but they are only guides. No

particular set of detailed rules for

counsel's conduct can satisfactorily take

account of the variety of circumstances

faced by defense counsel or the range of

legitimate decisions regarding how best to

represent a criminal defendant.

Id. at

688-89, 104 S.Ct. at 2065.

A

reviewing court's scrutiny "of counsel's

performance must be highly deferential." Id.

There is a strong presumption that "counsel's

conduct falls within the wide range of

reasonable professional assistance; that is,

the defendant must overcome the presumption

that, under the circumstances, the

challenged action 'might be considered sound

trial strategy.' " Id.

In

deciding whether counsel's performance was

deficient, we must judge the challenged

conduct based on the facts of the particular

case, "viewed as of the time of counsel's

conduct." Id. at 690, 104 S.Ct. at 2066. We

must determine whether, "in light of all the

circumstances, the identified acts or

omissions were outside the wide range of

professionally competent assistance,"

keeping in mind that "counsel is strongly

presumed to have rendered adequate

assistance and made all significant

decisions in the exercise of reasonable

professional judgment." Id. "[S]trategic

choices made after thorough investigation of

law and facts relevant to plausible options

are virtually unchallengeable." Id.

In

analyzing counsel's performance, "[w]e will

neither second-guess counsel's decisions,

nor apply the fabled twenty-twenty vision of

hindsight." Campbell v. Wood, 18 F.3d 662,

673 (9th Cir.), cert. denied, 511 U.S. 1119,

114 S.Ct. 2125, 128 L.Ed.2d 682 (1994). "A

fair assessment of attorney performance

requires that every effort be made to

eliminate the distorting effects of

hindsight, to reconstruct the circumstances

of counsel's challenged conduct, and to

evaluate the conduct from counsel's

perspective at the time." Strickland, 466

U.S. at 689, 104 S.Ct. at 2065.

Karl

claims that his counsel's performance was

deficient in numerous ways. We will discuss

each claim of ineffectiveness individually.a.

Impulsivity Defense

Karl

claims that his background and his

statements to the police indicate that he

murdered Hartsock in a moment of rage after

being kicked. He argues that this moment of

rage and his "notorious lack of control"

showed that he committed this crime on

impulse and did not premeditate the crime.

Thus, he claims that his attorney acted

deficiently by failing to thoroughly

investigate or pursue a defense of

impulsivity on his behalf. The district

court held that Karl's counsel was not

ineffective on this issue, see LaGrand v.

Lewis, 883 F.Supp. 451, 457-58 (D.Ariz.1995),

and we agree.

In State

v. Christensen, 129 Ariz. 32, 35-36, 628

P.2d 580, 583-84 (1981), the Arizona Supreme

Court recognized that impulsivity could be a

viable defense for premeditated murder

because it tends to negate the mental

element of premeditation. The defendant in

Christensen was charged with having

committed the premeditated murder of his

wife. There was no evidence supporting a

claim of felony murder. Therefore, the

defendant could be found guilty of first-degree

murder only if he was found to have

premeditated the murder.

As found

by the district court, Karl's counsel was

clearly aware of the Christensen impulsivity

defense. Prior to his representation of

Karl, counsel represented a defendant in a

case in which the impulsivity defense and

Christensen were discussed. See State v.

Ramos, 133 Ariz. 12, 648 P.2d 127 (App.1981),

vacated, 133 Ariz. 4, 648 P.2d 119 (1982).

Furthermore, Karl's counsel did not ignore

evidence of defendant's impulsivity.

Impulsivity evidence was presented during

trial through the testimony of Walter and

argued by Karl's attorney during closing

argument. However, counsel apparently made a

decision to not pursue the impulsivity

defense more fully.9

Such a

decision is supported by the record, which

reveals the futility of an impulsivity

defense. As the district court stated:

Prior to Ken Hartsock

being stabbed, Walter LaGrand had stated

that he was going to kill the bank manager

if the bank manager was lying about being

unable to open the vault. Before Dawn Lopez

was permitted to leave the bank to turn off

her headlights, she was told that if she did

not return, Ken Hartsock would be killed.

The bank manager was

stabbed twenty-four times and Dawn Lopez was

stabbed at least seven times. After Ken

Hartsock was repeatedly stabbed, either

[Karl] or Walter LaGrand was overheard to

say: "Just make sure he's dead." Ms. Lopez

testified that she heard both [Karl] and

Walter LaGrand make such a statement. This

evidence belies a claim of impulsivity.

LaGrand,

883 F.Supp. at 458.

Karl's

present counsel have spent much time and

effort in gathering further evidence and

opinion to support the impulsivity defense.

However, fleshing it out further makes it no

better. Karl's presentation does not

overcome the presumption of soundness under

Strickland. Impulsivity was absolutely no

defense to the felony-murder charge, which

was the State's principal claim.

In fact,

premeditated murder remained in the case

only because the trial court rejected the

State's objection to the defendants'

requested instruction on premeditated murder.

In addition, pursuit of the impulsivity

defense, like the insanity defense, would

have necessarily brought Karl's prior record

into the case. Counsel's performance was not

deficient. See Strickland, 466 U.S. at 691,

104 S.Ct. at 2066-67.

Karl

claims that his attorney rendered

ineffective assistance by failing to pursue

an insanity defense. We reject this claim.

Karl's

counsel researched the possibility of an

insanity defense at length. Karl was

examined by two doctors, psychologist Dr.

Lewis Hertz and psychiatrist Dr. Edward

Meshorer. Neither doctor's reports suggested

an insanity defense was available to Karl.

Dr. Hertz reported that Karl "knew right

from wrong," negating use of the M'Naughten

test for insanity. Dr. Meshorer's report,

while not addressing the M'Naughten test,

gave no indication that an insanity defense

would be a viable option for Karl. As the

Arizona Supreme Court pointed out: "[N]o

evidence of M'Naughten insanity existed."

State v. LaGrand, 152 Ariz. 483, 485, 733

P.2d 1066, 1068 (1987).

Furthermore, if Karl's counsel had pursued

an insanity defense, Arizona procedure would

have opened up Karl's juvenile record to

inspection and exposed his past to scrutiny.

See State v. Rodriguez, 126 Ariz. 28, 31,

612 P.2d 484, 487 (1980). As the district

court stated:

Had [Karl's]

counsel opened the door to [Karl's] past,

the jury would have learned of a lengthy and

violent criminal history. [Karl's]

presentence reports indicate that less than

three months before the events of this case

occurred, on two separate occasions [Karl]

committed armed robberies and kidnappings at

Tucson grocery stores, and had prepared to

commit another armed robbery at a third

grocery store. When the murder of Ken

Hartsock occurred, [Karl] had been released

on bail while awaiting trial for armed

robbery and kidnapping.

As a

juvenile, [Karl] was adjudicated delinquent

for multiple burglaries, armed robbery and

kidnapping.

LaGrand,

883 F.Supp. at 458.

Because

there was a lack of evidence supporting an

insanity defense, and because pursuing an

insanity defense would have made Karl's

lengthy and violent criminal history

admissible, counsel's decision not to pursue

the insanity defense was reasonable and did

not constitute ineffective assistance.

c. Suppression of

Karl's Confession

After

being arrested, Karl made two confessions to

the police wherein he admitted committing

the murder and stated that it was done in a

moment of rage. Karl's previous attorney

succeeded in having the confessions

suppressed on the grounds that the

confessions were involuntary and that Karl

had not received his Miranda warnings.

After

Karl's trial counsel became the lead counsel,

he decided that the confessions would be

useful at sentencing. The confessions

contained statements that made the murder

seem less heinous than the eyewitness

testimony of Ms. Lopez. If Karl was

convicted of first-degree murder, counsel

wanted to use the confessions at sentencing

in order to mitigate the sentence. Trial

counsel sought reversal of the trial court's

decision of involuntariness. The trial court

agreed, and although the statements were

inadmissible at trial due to the lack of a

Miranda warning, the statements became

admissible at sentencing.

Karl

claims that his counsel acted ineffectively

because counsel changed strategies on

whether or not the confessions should be

suppressed. We reject this claim.

Previous

counsel's decision to seek suppression of

the confessions was reasonable. The

confessions, while evidencing impulsivity,

also contained statements that were highly

incriminating because they tended to place

the entire blame for Hartsock's death on

Karl. Previous counsel believed that Karl

was confessing to something that he did not

do. Eyewitness testimony contradicted what

Karl had confessed to. Thus, previous

counsel believed that Karl's confessions

would be harmful to the case and therefore

made a decision to seek suppression, an

effort in which trial counsel participated.

Trial

counsel's decision to seek retraction of the

trial court's ruling to the extent that the

confessions were involuntary was also

reasonable. This enabled counsel to exclude

the confessions when they would have been

the most damaging--during the guilt finding

phase--and utilize them at a time when they

could prove useful--during sentencing.

However,

Karl claims that the use of the confessions

at sentencing was only useful to Walter and

that trial counsel's decision to have the

confessions admissible during sentencing was

therefore ineffective. We disagree. The

confessions revealed a less egregious crime

than that presented by the eyewitness

testimony of Ms. Lopez. The sentencing was

to be done by the trial judge, who would

have already heard Ms. Lopez's testimony.

Thus,

counsel introduced the confessions at the

sentencing phase, with the possibility that

Karl's version of the events would offset

the testimony of Ms. Lopez. In the absence

of the confessions, the sentencer would have

no record evidence of Karl's conduct except

that of Ms. Lopez. This use of Karl's

confessions during sentencing was a sound

and reasonable strategic decision by Karl's

trial counsel and, as such, does not

constitute ineffective assistance.

d. Interview and

Examination of Witnesses

Karl

argues that his counsel acted ineffectively

by failing to interview and examine all of

the witnesses at trial. We are not persuaded.

Prior to

the time that trial counsel was appointed to

represent Karl, all of the witnesses had

been interviewed. Trial counsel reviewed the

transcripts of these interviews. An

investigator had also been working on the

case prior to trial counsel's appointment,

and trial counsel had access to, and

reviewed, this investigator's reports. Trial

counsel put in the equivalent of twenty-seven

eight-hour days in trial preparation. He

personally interviewed the only eyewitness,

Ms. Lopez. The fact that trial counsel did

not personally interview each witness does

not constitute ineffective assistance. See

Eggleston v. United States, 798 F.2d 374,

376 (9th Cir.1986) (trial counsel does not

need to interview a witness if the witness's

account is fairly known to counsel).

At trial,

Karl's trial counsel was very quiet. Of the

eighteen witnesses called by the Government,

trial counsel cross-examined only two. One

of the witnesses cross-examined by trial

counsel was Ms. Lopez.

The

Arizona Supreme Court held:

Although

trial counsel here kept an exceedingly low

profile, we cannot say that his performance

was so deficient as to compromise the

adversarial nature of the trial.... Failure

to cross-examine most witnesses was not

deficient because co-defendant's counsel did

an excellent job of cross-examining them.

Counsel did cross-examine Dawn Lopez, and

establish that Karl was kicked. While we

normally expect to see more vigorous

representation from counsel, particularly in

a death penalty case, we cannot say that

counsel's trial performance was ineffective.

LaGrand,

152 Ariz. at 486, 733 P.2d at 1069. We agree.

The trial

court's sequence of examination of witnesses

resulted in Walter's counsel cross-examining

each of the State's witnesses prior to

Karl's trial counsel having that opportunity.

All parties agree that Walter's counsel did

an exceptional job cross-examining the

witnesses. Thus, there was not much left to

cross-examine when Karl's counsel was

allowed to address the witness. If Karl's

counsel repeated the questions asked by

Walter's counsel, any negative answers would

simply have been magnified in the jury's

mind. Karl's counsel made a reasonable

decision not to add to the questioning of

most of the witnesses.

The

strategies of respective defense counsel at

trial were not nearly as antagonistic as

Karl now urges. The evidence against Karl

and Walter overlapped. Questions asked by

Walter's counsel often inured to the benefit

of Karl. In fact, both brothers had the same

interests as against each witness except Ms.

Lopez.

Walter's

counsel presented expert testimony regarding

flaws associated with eyewitness testimony