August 19, 2004

THE PEOPLE, PLAINTIFF AND RESPONDENT,

v.

JAMES GREGORY MARLOW AND CYNTHIA LYNN COFFMAN, DEFENDANTS AND

APPELLANTS.

Court: Superior County: San Bernardino Judge: Don

A. Turner *fn1 San Bernardino County Super. Ct. No. SCR-45400

The opinion of the court was delivered by: Werdegar,

J.

(this opn. should precede P. v. Marlow, S026614,

also filed 8/19/04)

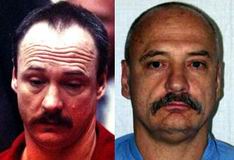

A San Bernardino County jury convicted James

Gregory Marlow and Cynthia Lynn Coffman of one count of each of the

following offenses: murder (Pen. Code, § 187), kidnapping (§ 207, subd.

(a)), kidnapping for robbery (§ 209, subd. (b)), robbery (§ 211),

residential burglary (§ 459) and forcible sodomy (§ 286, subd. (c)).

The same jury found true as to both defendants special circumstance

allegations that the murder was committed in the course of, or

immediate flight from, robbery, kidnapping, sodomy and burglary within

the meaning of section 190.2, subdivision (a)(17)(A), (B), (D) and

(G). The jury further found that Coffman and Marlow were personally

armed with a firearm. (§ 12022, subd. (a).) Following Marlow's waiver

of a jury trial on allegations that he had suffered two prior serious

felony convictions within the meaning of section 667, subdivision (a),

the trial court found those allegations to be true. The jury returned

a verdict of death, and the trial court entered judgment accordingly.

This appeal is automatic. (§ 1239, subd. (b).) We affirm the judgment

in its entirety.

I. Facts

A. Guilt Phase

1. Prosecution's case-in-chief

On Friday, November 7, 1986, around 5:30 p.m.,

Corinna Novis cashed a check at a First Interstate Bank drive-through

window near the Redlands Mall, after leaving her job at a State Farm

Insurance office in Redlands. Novis, who was alone, was driving her

new white Honda CRX automobile. Novis had been scheduled for a

manicure at a nail salon owned by her friend Terry Davis; she never

arrived for the appointment. Novis also had planned to meet friends at

a pizza parlor by 7:00 that evening, but she never appeared.

That same day, Coffman and Marlow went to the

Redlands Mall, where Marlow's sister, Veronica Koppers, worked in a

deli restaurant. Between 5:00 and 5:30 p.m., Veronica pointed the

couple out to her supervisor as they sat in the mall outside the deli.

Coffman was wearing a dress; Marlow, a suit and tie. Later, at the

time they had arranged to pick Veronica up from work, Coffman and

Marlow entered the deli and handed Veronica her car keys, explaining

they had a ride.

Around 7:30 p.m., Coffman and Marlow brought Novis

to the residence of Richard Drinkhouse. Drinkhouse, who was recovering

from injuries sustained in a motorcycle accident and had some

difficulty walking, was home alone in the living room watching

television when the three arrived. Marlow was wearing dress trousers;

Coffman was still wearing a dress; and Novis wore jeans, a black and

green top, and had a suit jacket draped over her shoulders. Marlow

told Drinkhouse they needed to use the bedroom, and the three walked

down the hallway. The women entered the bedroom. Marlow returned to

the living room and told Drinkhouse they needed to talk to the girl so

they could "get her ready teller number" in order to "rob" her bank

account. Drinkhouse complained about the intrusion into his house and

asked Marlow if he were crazy. Marlow replied in the negative and

assured Drinkhouse "there won't be any witnesses. How is she going to

talk to anybody if she's under a pile of rocks?" Drinkhouse asked

Marlow to leave with the women. Marlow declined, saying he was waiting

for Veronica to bring some clothing. He told Drinkhouse to stay on the

couch and watch television.

Knowing Marlow had a gun and having previously

observed him fight and beat another man, and also being aware of his

own physical disability, Drinkhouse was afraid to leave the house. At

one point, when Drinkhouse appeared to be preparing to leave, he saw

Coffman, in the hallway, gesture to Marlow, who came out of the

bedroom to ask where he was going. Drinkhouse then returned to his

seat on the couch in front of the television.

Veronica arrived at the Drinkhouse residence 10 to

15 minutes after Coffman, Marlow and Novis. Marlow came out of the

bedroom, told Veronica he "had someone [t]here" and cautioned her not

to "freak out" on him. Marlow said he needed something from the car;

Coffman and Veronica went outside and returned with a brown tote bag.

About 10 minutes later, Coffman drove Veronica to a nearby 7-Eleven

store in Novis's car, leaving Marlow in the bedroom with Novis.

Drinkhouse heard Novis ask Marlow if they were going to take her home;

Marlow answered, "As soon as they get back." Veronica testified that,

during this period, Coffman did not appear frightened or ask her for

help in escaping from Marlow. Drinkhouse likewise testified Coffman

appeared to be going along willingly with what Marlow was doing.

Upon returning from the 7-Eleven store, Coffman

entered the bedroom where Marlow was holding Novis prisoner and

remained with them for 10 to 15 minutes. During this time, Drinkhouse

heard the shower running. After the shower was turned off, Marlow

emerged from the bedroom wearing pants but no shoes or shirt; he had a

towel over his shoulders and appeared to be wet. He walked over to

Veronica, said, "We've got the number," and started going through a

purse, removing a wallet and identification. Marlow then returned to

the bedroom with the purse. Veronica left the house. About five

minutes later, Coffman, dressed in jeans, emerged from the bedroom,

followed by Novis, handcuffed and with duct tape over her mouth, and

Marlow. Novis's hair appeared to be wet. The three then left the house.

Drinkhouse never saw Novis again.

Marlow and Coffman returned the following afternoon

to ask if Drinkhouse wanted to buy an answering machine or knew anyone

who might. When Drinkhouse responded negatively, the two left.

Novis's body was found eight days later, on

November 15, in a shallow grave in a vineyard in Fontana. She was

missing a fingernail on her left hand, and her shoes and one earring

were gone. An earring belonging to Novis was later found in Coffman's

purse. Forensic pathologist Dr. Gregory Reiber performed an autopsy on

November 17. Dr. Reiber concluded that Novis had been killed between

five and 10 days previously. Marks on the outside of her neck,

injuries to her neck muscles and a fracture of her thyroid cartilage

suggested ligature strangulation as the cause of death, but

suffocation was another possible cause of death due to the presence of

a large amount of soil in the back of her mouth. Marks on her wrists

were consistent with handcuffs, and sperm were found in her rectum,

although there was no sign of trauma to her anus.

When Novis uncharacteristically failed to appear

for work on Monday, November 10, without calling or having given

notice of an intended absence, her supervisor, Jean Cramer, went to

Novis's apartment to check on her. Cramer noticed Novis's car was not

parked there, the front door was ajar, and the bedroom was in some

disarray. Cramer reported these observations to police, who found no

sign of a forced entry. Terry Davis went to Novis's apartment later

that day and determined Novis's answering machine and typewriter were

missing.

Around 9:30 p.m. on Friday, November 7, the night

Novis apparently was killed, Veronica Koppers visited her friend Irene

Cardona and tried to sell her an answering machine, later identified

as the one taken from Novis's apartment. Cardona accompanied Veronica,

Coffman and Marlow to the house of a friend, who agreed to trade the

answering machine for a half-gram of methamphetamine. The next day,

Debra Hawkins bought the answering machine that Cardona had traded.

The Redlands Police Department eventually recovered the machine.

Harold Brigham, the proprietor of the Sierra Jewelry and Loan in

Fontana, testified that on November 8, Coffman pawned a typewriter,

using Novis's identification.

Victoria Rotstein, the assistant manager of a Taco

Bell on Pacific Coast Highway in Laguna Beach, testified that between

11:00 p.m. and 12:00 a.m. one night in early November 1986, after the

restaurant had closed for the evening, a woman came to the locked door

and began shaking it. When told the restaurant was closed, the woman

started cursing, only to run off when Rotstein said she was going to

call the police. Rotstein identified Coffman in a photo lineup and a

physical lineup, but did not identify her at trial. On November 11,

1986, the Taco Bell manager found a bag near a trash receptacle behind

the restaurant; inside the bag were Coffman's and Novis's drivers'

licenses, Novis's checks and bank card, and various identification

papers belonging to Marlow.

The day after Novis's disappearance, Marlow,

Coffman and Veronica Koppers returned to Paul Koppers's home; Marlow

asked him if he could get any "cold," i.e., nontraceable, license

plates for the car. On the morning of November 12, Marlow and Coffman

returned to Paul Koppers's residence, where they told him they had

been down to "the beach," "casing out the rich people, looking for

somebody to rip off." Koppers asked Marlow if he knew where Veronica

was; after placing two telephone calls, Coffman learned Veronica was

in police custody. On the Koppers' coffee table, Marlow saw a

newspaper containing an article about Novis's disappearance with a

photograph of her car. Marlow told Coffman they had to get rid of the

car. Paul Koppers refused Marlow's request to leave some property at

his house.

Coffman and Marlow left the Koppers residence and

drove to Big Bear, where they checked into the Bavarian Lodge using a

credit card belonging to one Lynell Murray (other evidence showed

defendants had killed Murray on November 12). Their subsequent

purchases using Murray's credit card alerted authorities to their

whereabouts, and they were arrested on November 14 as they were

walking on Big Bear Boulevard, wearing bathing suits despite the cold

weather. Coffman had a loaded .22-caliber gun in her purse. Novis's

abandoned car was found on a dirt road south of Santa's Village, about

a quarter-mile off Highway 18. Despite Coffman's efforts to wipe their

fingerprints from the car, her prints were found on the license plate,

hood and ashtray; a print on the hood of the car was identified as

Marlow's. A resident of the Big Bear area later found discarded on his

property a pair of gray slacks with handcuffs in the pocket, as well

as a receipt and clothing from the Alpine Sports Center, where Coffman

and Marlow had made purchases.

2. Marlow's case

Dr. Robert Bucklin, a forensic pathologist,

reviewed the autopsy report and related testimony by Dr. Reiber. Based

on the lack of anal tearing or other trauma, Dr. Bucklin opined there

was insufficient evidence to establish that Novis had suffered anal

penetration. He also questioned Dr. Reiber's conclusion that Novis

might have been suffocated, as opposed to aspirating sandy material

during the killing or coming into contact with it during the burial

process.

3. Coffman's case

Coffman testified on her own behalf, describing her

relationship with Marlow, his threats and violence toward her, and

other murders in which, out of fear that he would harm her or her son,

she had participated with him while nonetheless lacking any intent to

kill. Coffman also presented the testimony of Dr. Lenore Walker, a

psychologist and expert on battered woman syndrome, in support of her

defense that she lacked the intent to kill. The trial court admitted

much of this evidence over Marlow's objections.

Coffman testified she was born in St. Louis,

Missouri, in 1962 and, following her graduation from high school, gave

birth to a son, Joshua, in August 1980. Shortly thereafter she married

Joshua's father, Ron Coffman, from whom she separated in April 1982.

In April 1984, Coffman left St. Louis for Arizona, leaving Joshua in

his father's care, intending to come back for him when she was settled

in Arizona.

Coffman testified that when she met Marlow in April

1986, she was involved in a steady relationship with Doug Huntley. She

and Huntley had lived in Page, Arizona, before moving to Barstow,

where Huntley took a job in construction. Coffman, who previously had

worked as a bartender and waitress, was briefly employed in Barstow

and also sold methamphetamine. In April 1986, both Coffman and Huntley

were arrested after an altercation at a 7-Eleven store in which

Coffman pulled a gun on several men who were "hassling" Huntley and "going

to jump him." Charged with possession of a loaded weapon and

methamphetamine, Coffman was released after five days. The day after

she was released, Marlow, whom she had never met, showed up at the

apartment she shared with Huntley. Marlow said he had been in jail

with Huntley and had told him he would check on Coffman to make sure

she was all right. Coffman and Marlow spent about an hour together on

that occasion and smoked some marijuana. After Huntley's release, he

and Coffman visited Marlow at the Barstow motel where Marlow was

staying.

By June 1986, Huntley was again in custody and

Coffman was preparing to leave him when Marlow reappeared at her

apartment. At Marlow's request, Coffman drove him to the home of his

cousin, Debbie Schwab, in Fontana; while there, he purchased

methamphetamine. Within a few days, Coffman moved with Marlow to

Newberry Springs, where they stayed with Marlow's friends Steve and

Karen Schmitt. During this period, Marlow told her he was a hit man, a

martial arts expert and a White supremacist, and that he had killed

Black people in prison. In Newberry Springs, Coffman testified, Marlow

for the first time tied her up and beat her after accusing her of

flirting with another man. During this episode, his demeanor and voice

changed; she referred to this persona as Folsom Wolf, after the prison

where Marlow had been incarcerated, and over the course of her

testimony identified several other occasions when Marlow had seemed to

become Wolf and behaved violently toward her. After this initial

beating, he apologized, said it would never happen again, and treated

her better for a couple of days. She discovered he had taken her

address book containing her son's and parents' addresses and phone

numbers, and he refused to give it back. He became critical of the way

she did things and when angry with her would call her names. He

refused to let her go anywhere without him, saying that if she ever

left him, he would kill her son and family.

After some weeks in Newberry Springs, Marlow told

Coffman his father had died and left him some property in Kentucky and

that they would go there. Coffman would get her son back, he suggested,

and they would live together in Kentucky or else sell everything and

move somewhere else. Marlow prevailed on her to steal a friend's truck

for the journey; after having it repainted black, they set off. Not

long before they left, Marlow bit her fingernails down to the quick.

They went by way of Colorado, where they stayed with a former

supervisor of Marlow's, Gene Kelly, who discussed the possibility of

Marlow's working for him again in Georgia. They then passed through St.

Louis. Arriving in the evening and reaching her parents by telephone

at midnight, Coffman was told it was too late for her to visit that

night; the next morning, Marlow told her there was no time for her to

see her son. Accordingly, although Coffman had not seen her son since

Christmas 1984, they drove straight to Kentucky.

On arriving, they stayed with Marlow's friend Greg

("Lardo") Lyons and his wife Linda in the town of Pine Knot. Marlow

informed Coffman the real reason for the trip was to carry out a

contract killing on a "snitch." Once they had located the intended

victim's house, Marlow told her she was to do the killing. She

protested, but ultimately did as he directed, carrying a gun,

fashioning her bandana into a halter top, and luring the victim out of

his house on the pretext of needing help with her car. When the victim,

who had a gun tucked into his belt, had come to the spot where their

truck was parked and was taking a look under the hood, Marlow appeared

and demanded to know what the man was doing with his sister. Marlow

then grabbed the man's gun. Coffman testified she heard a shot go off,

but did not see what happened. Coffman and Marlow returned to Lyons's

home. Sometime later, Marlow and Lyons left the house and returned

with a wad of money. Coffman counted it: there was $5,000.

Coffman testified that Marlow subjected her to

several severe beatings in Kentucky. In mid-August 1986, they drove to

Atlanta, where Marlow told her he had a job. While in a bar after his

fourth day working for Gene Kelly, Marlow became angry at Coffman.

That night, in their hotel room, he began beating her, took a pair of

scissors, threatened to cut her eye out, and then cut off all her hair.

He forced her out of the motel room without her clothes, let her back

in and forcibly sodomized her. Marlow failed to show up for work the

next day and was fired. They then returned to Kentucky, where they

unsuccessfully attempted a burglary and spent time going on "pot hunts,"

i.e., searching rural areas for marijuana plants to steal. Just before

they left Kentucky to go to Arizona, they stole a station wagon.

Back in Arizona, they burglarized Doug Huntley's

parents' house and stole a safe. After opening it to find only some

papers and 10 silver dollars, they took the coins and buried the safe

in the desert. Returning to Newberry Springs and again briefly staying

with the Schmitts, they sold the stolen car and stole two rings

belonging to their hosts, pawning one and trading the other for

methamphetamine.

From Newberry Springs, in early October 1986,

Marlow and Coffman took a bus to Fontana, where they again stayed with

Marlow's cousins, the Schwabs. During that visit, Marlow tattooed

Coffman's buttocks with the words "Property of Folsom Wolf" and her

ring finger with the letters "W-O-L-F" and lightning bolts, telling

her it was a wedding ring. Leaving the Schwab residence in late

October, they hitchhiked to the house of Rita Robbeloth and her son

Curtis, who were friends of Marlow's sister, Veronica. From there,

Veronica brought Coffman and Marlow to the home she shared with her

husband, Paul, and his brother, Steve. At the Robbeloths' one day,

Coffman, Marlow and Veronica were sharing some methamphetamine, and

Marlow became enraged over Coffman's request for an equal share.

Although Coffman quickly backed down, Marlow began punching her and

threatened to leave her by the side of the road. Later, back at the

Koppers' residence, Marlow continued to beat, kick and threaten to

kill her, forced her to consume four pills he told her were cyanide,

extinguished a cigarette on her face and stabbed her in the leg,

rendering her unconscious for a day and unable to walk for two days.

Coffman recounted how she and Marlow, along with

Veronica, left the Koppers' and came to stay at the Drinkhouse

residence the night before they abducted Novis. On the morning of

November 7, 1986, Marlow told her to put on a dress, saying they would

not be able to rob anyone if they were not dressed nicely. Marlow

borrowed a suit from Curtis Robbeloth and told Coffman they had to "get

a girl." She testified she did not understand he intended to kill the

girl. After dropping Veronica off at her job, Coffman and Marlow drove

around in Veronica's car looking for someone to rob. Eventually they

parked in front of the Redlands Mall. When they saw Novis's white car

pull up in front of them and Novis enter the mall, Marlow said, "That

is the one we are going to get," despite Coffman's protests that the

girl was too young to have money. He directed Coffman to get out of

the car and ask Novis for a ride when the latter returned to her car.

Coffman complied, asking Novis if she could give them a ride to the

University of Redlands. When Novis agreed, Marlow got in the two-seater

car with Coffman on his lap. As Novis drove, Marlow took the gun from

Coffman, displayed it and told Novis to pull over. Then Coffman drove

while Novis, handcuffed, sat on Marlow's lap. He told Novis they were

going to a friend's house and directed Coffman to the Drinkhouse

residence, where they arrived between 7:00 and 7:30 p.m. When Novis

told them she had something to do that evening, Marlow assured her, "Oh,

you'll make it where you are going. Don't worry."

As Marlow went in and out of the bedroom at the

Drinkhouse residence, Coffman sat with Novis. When Novis asked if she

was going to be allowed to leave, Coffman told her to do what Marlow

said and he would let her go. Showing Novis the stab wound on her leg,

Coffman told her Marlow was "just crazy." Marlow dispatched Coffman to

make coffee and proceeded to try to get Novis to disclose her personal

identification number (PIN). Finally Novis gave him a number. Marlow

then taped Novis's mouth and said, "We are going to take a shower." He

removed Novis's clothes and put her, still handcuffed, into the shower.

Coffman testified he told her (Coffman) to get into the shower, but

she refused. Thinking Marlow was going to rape Novis, Coffman

testified she "turned around" and "walked away" into the living room.

There she retrieved her jeans and returned to the bedroom to get

dressed. Coffman denied either arousing Marlow sexually or having

anything to do with anything that happened in the shower. When Marlow

told her to dress Novis, Coffman responded that if he uncuffed her,

she could do so herself. He removed the handcuffs to permit Novis to

dress, then handcuffed her again to a bedpost.

Around this time, Veronica arrived at the

Drinkhouse residence. Marlow took Novis's purse, directed Veronica to

get his bag out of her car, and told Coffman and his sister to go to

the store, where they bought sodas and cigarettes. Back at the

Drinkhouse residence, Veronica departed and, soon thereafter, Marlow,

Coffman and Novis left, with Coffman driving and Novis, duct tape on

her mouth, handcuffed, and covered with blankets, in the back of the

car. Marlow told Coffman to drive to their drug connection in Fontana,

but directed her into a vineyard. There, Marlow and Novis got out of

the car, and he removed her handcuffs and tape. He explained they

could not bring a stranger to the drug connection's house, so he would

wait there with Novis while Coffman scored the dope. They walked off,

with Marlow carrying a blanket and a bag containing a shovel.

Coffman testified she felt confused at that point

because she possessed only $15, insufficient funds for a drug purchase.

Believing Marlow intended to rape Novis, she backed the car out of the

vineyard, parked down the street and smoked a cigarette. When she

returned, no one was there. She could hear the sound of digging. Some

10 to 15 minutes later Marlow reappeared, alone. Without speaking, he

threw some items into the back of the car and, after Coffman had

driven for a while, began to hit her and berated her for driving away.

They returned to the Robbeloths' house, where

Marlow changed clothes. Next they drove to a First Interstate Bank

branch, but were unable to access Novis's account because she had

given them the wrong PIN. From there, around 9:30 p.m., they went to

Novis's apartment and, after a search, found a card on which Novis had

written her PIN. They also took a typewriter, a telephone answering

machine and a small amount of cash. They returned to the Robbeloths',

where Marlow spoke with Veronica, who then drove them around

unsuccessfully looking for a friend to buy the machine. Leaving

Veronica around 3:00 or 4:00 a.m., Coffman and Marlow tried again to

access Novis's account, only to learn there was not enough money in

the account to enable them to withdraw funds using the automated

teller. They returned to the Drinkhouse residence.

The next morning, Veronica joined them around 8:00

or 9:00. After trying again to sell the answering machine, they pawned

the typewriter for $50 and bought some methamphetamine. That afternoon

Coffman and Marlow went to Lytle Creek to dispose of Novis's

belongings. Coffman had not asked Marlow what had happened to Novis;

she testified she did not want to know and thought he had left her

tied up in the vineyard. They returned to the Drinkhouse residence

around 5:00 p.m. Later that evening, after trading the answering

machine for some methamphetamine in the transaction described in Irene

Cardona's testimony, Coffman and Marlow went with Veronica to the

Koppers residence, where they "did some speed" and developed a plan to

go to the beach in Orange County on Marlow's theory that "it would be

easier to get money down there because all rich people live down at

the beach." Veronica drove Coffman and Marlow back to Novis's car,

which they drove to Huntington Beach, arriving at sunrise.

After lying on the beach for several hours, they

looked unsuccessfully for people to rob. Marlow berated Coffman for

their inability to find a victim, held a gun to her head and ordered

her to drive. After threatening to shoot her, he began to punch the

stab wound on her leg. That night, they slept in the car in front of

some houses near the beach. The next day, Coffman cashed a check on

Novis's account, receiving $15. They continued their search for a

potential victim and eventually bought dinner at a Taco Bell, where

Marlow discarded their identification, along with Novis's. They drove

up into the hills and spent the night. The next day, they resumed

their search for someone to rob. Seeing a woman walking out of Prime

Cleaners, Marlow commented that she would be a good one to rob. They

continued to drive around, however, and spent the night in the car

behind a motel on Pacific Coast Highway after removing the license

plates from another car and putting them on Novis's car.

The following afternoon, Coffman and Marlow entered

Prime Cleaners and committed the robbery, kidnapping, rape and murder

of Lynell Murray detailed below (see post, at pp. 25-28).

Coffman also presented the testimony of several

witnesses suggesting her normally outgoing personality underwent a

change and that she behaved submissively and fearfully after she

became Marlow's girlfriend. Judy Scott, Coffman's friend from Page,

Arizona, testified that when Coffman and Marlow visited her in October

1986, Coffman, who previously had been talkative and concerned about

the appearance of her hair, avoided eye contact with Scott, spoke

tersely and had extremely short hair that she kept covered with a

bandana. Lucille Watters testified that during the couple's July 1986

visit to her house, Coffman appeared nervous, rubbing her hands and

shaking. Linda Genoe, Lyons's ex-wife, testified she met Coffman in

June 1986 when she and Marlow visited her at her home in Kentucky.

Genoe observed that whenever Marlow wanted something, he would clap,

call "Cynful" and tell her what to do. Coffman would always sit at his

feet. On one occasion, Genoe saw Coffman lying on the floor of the

bedroom in which she was staying, naked and crying; Coffman did not

respond when Genoe asked what was wrong. The next morning, Genoe saw

scratches on Coffman's face and bruises around her neck, and Coffman

seemed afraid to talk about it. Once Genoe observed Coffman cleaning

between the spokes on Marlow's motorcycle with a toothbrush while

Marlow watched. While at Genoe's house, Coffman and Marlow got "married"

in a "biker's wedding."

Coffman also presented the testimony of

psychologist Lenore Walker, Ph.D., an expert in battered woman

syndrome. Dr. Walker opined that Coffman was generally credible and

suffered from battered woman syndrome, which she described as a

collection of symptoms that is a subcategory of posttraumatic stress

disorder. Certain features of defendants' relationship fit the profile

of a battering relationship: a pattern of escalating violence, sexual

abuse within the relationship, jealousy, psychological torture,

threats to kill, Coffman's awareness of Marlow's acts of violence

toward others, and Marlow's alcohol and drug abuse. Dr. Walker

administered the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory to

Coffman and diagnosed her as having posttraumatic stress disorder and

depression with dysthymia, a depressed mood deriving from early

childhood.

Officer Lisa Baker of the Redlands Police

Department testified that on November 15, 1986, she took Coffman to

the San Bernardino County Medical Center and there observed various

scratches and bruises on her arms and legs, a bite mark on her wrist,

and a partly healed inch-long cut on her leg. Coffman told Baker the

bruises and scratches came from climbing rocks in Big Bear.

Gene Kelly, formerly Marlow's supervisor in his

employment with a company that erected microwave towers, testified

that one evening in June 1986 he saw Marlow, who believed Coffman had

been flirting with another man, yank her out of a restaurant door by

her hair.

4. Prosecution's rebuttal

Jailhouse informant and convicted burglar Robin

Long testified that in January 1987 she met Coffman in the San

Bernardino County jail. Coffman told Long that when Marlow took Novis

into the shower, she got in with them, and Marlow fondled both of them.

Coffman also told Long that Novis was alive and at the Drinkhouse

residence when Marlow and Coffman went to Novis's apartment to look

for her PIN. Coffman said she told Novis they would have to kill her

because they could not leave any victims alive. After Marlow killed

Novis, Coffman told Long, he came back to the car and got the shovel,

whereupon Coffman went with him into the vineyard and was present when

Novis was buried. Coffman told Long that killing Novis made her feel "really

good." Coffman also said they had taken a number of items from Novis,

including a watch, earrings and makeup.

With respect to Lynell Murray, Coffman told Long (contrary

to Coffman's trial testimony) that she had gotten into the shower with

Marlow and Murray. Coffman never told Long that Marlow had beaten her

or that the only reason she had participated in the killings was

because she was afraid for her son's safety.

The prosecution presented the testimony of several

police officers regarding Coffman's prior inconsistent statements.

Odie Lockhart, an officer with the Huntington Beach Police Department,

and other officers accompanied Coffman to the vineyard where Novis was

buried. Contrary to her testimony, Coffman did not tell Lockhart that

when Marlow took Novis into the vineyard, she had backed her car out;

rather, Coffman told him she stayed in the same location. When

Lockhart asked Coffman how Marlow had killed Novis, she said she "guessed"

he strangled her, but indicated she was only supposing. Contrary to

Coffman's testimony that she did not know Novis was dead when she and

Marlow went to Novis's apartment to search for her PIN, Coffman told

Sergeant Thomas Fitzmaurice of the Redlands Police Department in a

November 17, 1986, interview that the reason they did not ask Novis

for the correct PIN after the number Novis initially gave them did not

work was that "she was already gone by then." Despite Coffman's trial

testimony that Marlow had beaten her while they were holding Lynell

Murray at the motel in Huntington Beach, Fitzmaurice testified that

Coffman never mentioned such a beating during a formal interview at

the Huntington Beach Police Department and, indeed, said Marlow "wasn't

mean" to her.

Finally, to rebut Coffman's claim that she

continued to fear Marlow after her arrest, Deputy Blaine Proctor of

the San Bernardino County Sheriff's Department testified that he was

working courthouse security during September and October of 1987, and

while preparing Coffman and other inmates for transportation to court

on one occasion he noticed Coffman had left her holding cell and gone

to the area where Marlow was located. When he next saw Coffman, she

was in front of Marlow's cell; Marlow was standing on his bunk with

his hips pressed against the bars and Coffman was facing him with her

head level with his hips. When Coffman and Marlow observed Proctor,

Coffman stepped back and Marlow turned, revealing his genitals hanging

out of his jumpsuit. Marlow appeared embarrassed and told Proctor that

"nothing happened."

5. Marlow's rebuttal

Clinical psychologist Michael Kania testified,

based on Coffman's psychological test results and Dr. Walker's notes

and testimony, that Coffman was exaggerating her symptoms, was

possibly malingering, and did not suffer from posttraumatic stress

disorder, although she met most of the criteria for a diagnosis of

antisocial personality disorder.

Various individuals acquainted with both defendants

testified that Marlow and Coffman seemed to have a normal boyfriend-girlfriend

relationship and, although Coffman wore a bikini on many occasions,

the witnesses had never observed cuts or bruises on her.

Veronica Koppers testified that when she was around

Coffman, Coffman was under the influence of methamphetamine almost

every day. Coffman never expressed fear of Marlow for herself or her

son; instead, she wanted Marlow to get her son back for her by taking

the boy and "getting rid" of her ex-husband and former in-laws.

Coffman frequently nagged Marlow to acquire more money. With one

exception, all of the arguments between defendants that Veronica

witnessed were verbal and nonphysical. The one exception was an

argument that occurred while Veronica was driving defendants to a drug

connection to purchase methamphetamine. Coffman, in the front seat,

kept telling Marlow they needed to get more money to score speed and

to get Joshua; Marlow told her to shut up. Coffman kept it up and

Marlow slapped her. Veronica told both to get out of her car; they

complied. After defendants continued to argue for a few minutes,

Marlow got back into the car and told Coffman that if she wanted to

leave, she could. She begged him not to leave her. He said, "Okay, get

in [the car] and get off my back." Coffman got back into the car and

was silent. Veronica acknowledged that one day, after she had returned

home following work, Marlow told her he had accidentally stabbed

Coffman; the wound was a small puncture-type wound that did not bleed

a lot and, contrary to Coffman's testimony, Coffman did not seem to

have any trouble walking the next day.

Veronica testified that, at the Drinkhouse

residence on the night Novis was abducted, she saw Coffman going

through Novis's purse. She also saw Coffman coming out of the bedroom

wearing jeans and with wet hair.

Marlow testified he was not a member of or

affiliated with any prison gang and had never told Coffman he had been

a member of such a gang or had killed anyone while in prison. He

acknowledged to the jury that he had had several disciplinary write-ups

while in prison but claimed they were for verbal disrespect toward the

staff. He denied telling Coffman she would be killed if she ever left

him or threatening to have her son killed. He admitted he and Coffman

had had physical fights. He had never forced her to have sex, and

Coffman never told him she disliked oral sex. Contrary to Coffman's

testimony, they had had sex on the occasion when they first met.

Marlow acknowledged that during their stay in

Newberry Springs, he and Coffman had had two real arguments, but he

denied, contrary to Coffman's testimony, that on the first occasion he

kicked her, tore off her clothes, tied her up or threatened to kill

her. Instead, he had merely pushed her to the ground with an open hand.

On the second occasion, Coffman had rebuffed several of Marlow's

requests for assistance in painting a trailer, claiming she was busy

gluing together a broken nail; finally, Marlow claimed, he had bitten

off the broken nail and trimmed her other nails with a nail clipper.

Marlow testified that on their trip east in June 1986, Coffman had

declined to visit her mother on the morning following their arrival in

St. Louis. A few days after they reached Kentucky, Lyons and another

man approached Marlow about killing one Gregory Hill; Marlow testified

that, although he had told Coffman he would rather wait for an

expected job opening with his former supervisor, Gene Kelly, Coffman

told him the hit would be faster money. Finally, he agreed to do the

killing, and Lyons gave him a .22-caliber pistol to do the job. Marlow

testified he had never killed anyone before and, when he and Coffman

had parked their truck on a hill overlooking Hill's house, he

expressed reservations centering on whether Hill might have a wife and

children and whether in fact he might not have snitched as he was

alleged to have done. Coffman told him he was going to have to deal

with that and, when he said he could not, she demanded the gun and

told him she would deal with it. After Coffman got Hill to come and

take a look at the truck, Marlow, who had secreted himself in the

woods, noticed that Hill had a gun in his back pocket. Marlow emerged

and demanded to know what Hill was doing with his sister. When Hill

pulled out his gun, Marlow grabbed his arm and the gun went off in the

course of the struggle.

Later, Coffman expressed interest in a second

contract killing proposed to them, but Marlow balked at the idea.

During the ensuing argument, Coffman revealed that her ex-husband and

former in-laws had legal custody of her son, and she wanted them to "pay"

with their lives for taking him away from her. When Marlow refused to

kill them, she threatened to inform the police about the Hill killing;

the argument became heated, and he pushed her down; she got up and

slapped him, and he slapped her. Contrary to Coffman's testimony, he

did not kick her or hit her in the face with a clutch plate.

In Atlanta, after a few days of working for Gene

Kelly, Marlow agreed to Kelly's offer to take him and Coffman out for

dinner and drinks; Marlow felt reluctant, however, because Coffman had

been flirting with other men, and he was afraid of getting into

another argument with her in which the subject of the killing might

come up. They first went to a pool hall where, after drinking a lot of

tequila, Marlow got involved in an argument over Coffman with two

other men. Marlow told Coffman he wanted to leave the pool hall.

Entering a restaurant as the argument continued, Marlow became angry

when Coffman told him she was going to sleep with Kelly. He pulled her

out of the restaurant by the hair, and they went back to their motel

room. In the past, Marlow had threatened to cut her hair when she had

flirted with other men; this time, he did it. He denied Coffman's

accusations that he had threatened to put out her eye, beat her and

sodomized her.

Marlow testified he and Coffman returned to

Kentucky, where he was offered $20,000 to kill a pregnant woman in

Phoenix, Arizona; Marlow was not interested, but Coffman wanted him to

take the job or to get her to Arizona so that she could do it. They

traveled as far as Page, Arizona, before running out of money and

heading to Newberry Springs, where they stayed with the Schmitts for a

week. There, at Coffman's request, Marlow tattooed her ring finger and

buttocks.

In early October, Marlow and Coffman arrived at

Veronica's house. Marlow described the incident in which Coffman was

stabbed: High on methamphetamine, they had been arguing about money

and her son, Joshua; Coffman wanted him to take the contract to kill

the woman in Phoenix, but Marlow was unwilling. Coffman threatened to

"tell on [him] for Kentucky" if he did not, and said she would do the

job herself. Coffman was in bed, under the covers. Marlow stabbed the

bed, wounding Coffman's leg. Marlow asked one of the Koppers if they

had anything for pain, and they gave him Dilantin, which he in turn

gave to Coffman. Marlow denied Coffman's claim that he told her the

pills were cyanide and threatened to kill her.

Marlow recounted his version of the offenses

against Novis. On November 7, 1986, after moving to the Drinkhouse

residence, Marlow and Coffman discussed committing a robbery for money

to get Coffman to Arizona. After donning borrowed clothes that

afternoon, while they were waiting to pick up Veronica at the Redlands

Mall, Coffman noticed Novis pull up alongside their car and commented

that she wanted that car for the trip to Arizona. When Novis came out

of a store, Coffman asked her for a ride. She and Marlow got into the

car, and Novis started driving. Coffman nudged him several times to

pull out the gun. He did so and told Novis to pull over. Coffman took

over the wheel and, without any prompting from Marlow, drove to the

Drinkhouse residence. Marlow testified his intention at that point was

to take the car and get Novis to obtain money from her ATM.

At the Drinkhouse residence, they went straight

into the bedroom, where Coffman handcuffed Novis to the bed, took her

purse to the living room and searched it, finding an ATM card. Coffman

took Novis into the shower and asked Marlow to join them, saying she

wanted to see him have sex with Novis. Marlow entered the shower but

was not aroused by the prospect, and Coffman performed oral sex on him.

After getting out of the shower, Marlow took some money from Novis's

purse and asked Coffman to go to the store and get cigarettes. She and

Veronica did so. While they were gone, Drinkhouse asked Marlow for

$1,000 for bringing Novis to his house and told Marlow he could not

simply let her go because she would bring the police to his house.

Upon her return, Coffman too told him he could not just let Novis go.

Marlow, Coffman and Novis left the Drinkhouse

residence. Coffman was driving and, with no direction from Marlow,

drove to the vineyard. They argued and, Marlow testified, Coffman

insisted he "do something." He told her, "You do something." Coffman

said she wanted to get some speed. Marlow took a sleeping bag out of

the car and sat down with Novis while Coffman drove off. She returned

some 15 minutes later and commented, "You still haven't done anything."

Marlow told her to kill the lady if she wanted the lady killed. After

Coffman continued to insist, he put his arm around Novis from behind

and began choking her. Marlow testified he told Novis to lie down,

remain still until they left, and then get up and run away. He then

let go of her; she was lying on her side and still breathing. He

spread a little dirt over her, avoiding her head. Shown pictures of

the grave site, Marlow testified it did not look like that when he

left her. When he returned to the car, Coffman asked if he was sure

Novis was dead. He told her he was not sure and they left. When they

stopped by a field near the Drinkhouse residence, Marlow got out of

the car and waited in the field while Coffman took off. When she

returned, she asked him if he was okay.

Later, after an unsuccessful attempt to use Novis's

ATM card, Marlow and Coffman went to Novis's house. As they approached

the apartment, Marlow told Coffman they should not go in because he

did not think Novis was dead and the police might be watching; Coffman

told him not to worry.

Dr. Michael Kania testified about an interview he

had had with Marlow in January 1987. In that interview, Marlow

expressed a desire to protect Coffman and said he would do anything to

help her. Marlow told him that killing Novis was a response to his

wanting to "do good" and to hear Coffman tell him he "did good."

Marlow had only killed Novis, he told Kania, because of pressure from

Coffman and Drinkhouse.

6. Prosecution surrebuttal

To impeach Marlow's testimony, Sergeant Fitzmaurice

recounted statements obtained from him without waiver of the rights

described in Miranda v. Arizona (1966) 384 U.S. 436. Marlow told

Fitzmaurice, among other things, that the killing of Novis was "a

50-50" thing, and Coffman "got the ball rolling." Marlow indicated

both he and Coffman took Novis into the shower, but he was unable to

perform sexually despite Coffman's attempting to help him maintain an

erection. He also said that they had tried to use Novis's ATM card

after she was dead, that he did not tell Novis what was going to

happen to her, and that he had dug a hole for Novis's body with the

shovel the police later found at the Bavarian Lodge.

B. Penalty Phase

1. Prosecution's case in aggravation

In addition to the guilt phase evidence of the

offenses defendants committed against Corinna Novis, the prosecution's

case in aggravation included evidence that, on November 12, 1986,

Marlow and Coffman committed murder, rape and other offenses against

Lynell Murray, a young college student, in Orange County. The

prosecution also presented evidence that Marlow committed, and was

convicted on his plea of guilty to, three robberies in 1979 (§ 190.3,

factors (b) & (c)) and that, while incarcerated pending trial in the

present case, he committed an act of violence against a jail trustee (id.,

factor (b)). Aggravating evidence against Coffman consisted of an

incident of brandishing a deadly weapon and possessing a concealed

weapon, and an act of violence against her former boyfriend, Doug

Huntley.

a. Murder of Lynell Murray

On November 12, 1986, Lynell Murray failed to

return home from her job at Prime Cleaners in a Huntington Beach mall.

Around 6:00 p.m. that evening, a half-hour before Murray was to get

off work, Lynda Schafer drove into the parking lot of the mall and

noticed Coffman, dressed in tight jeans, walking in front of various

businesses in the mall. Schafer entered Prime Cleaners and left some

clothing with Murray, who was alone at the time. As Schafer left the

parking lot, she noticed Coffman passionately embracing a man, later

identified as Marlow, near an alley behind the cleaners.

About 6:30 p.m. that evening, Linda Whitlake was

leaving her health club, located near Prime Cleaners. As Whitlake

walked to her car, Coffman, cursing profanely, approached her,

claiming her new car would not start. When Whitlake agreed to give

Coffman a ride to her motel, down Pacific Coast Highway, Coffman said

she would go tell her boyfriend that Whitlake would drive them. Seeing

a man in a small white car with its hood up, Whitlake had misgivings,

locked her purse in her car and started over to tell them she had

changed her mind. Coffman met her halfway and said her boyfriend had

decided to telephone the auto club instead.

Around 7:00 p.m., a half-hour after Murray was

scheduled to get off work, her boyfriend Robert Whitecotton arrived at

Prime Cleaners, which appeared to have been burglarized and ransacked.

Murray's car was parked in the store's back lot. Whitecotton called

the police.

At 7:13 p.m., Coffman, wearing a black and white

dress, checked into room 307 of the Huntington Beach Inn. She

registered under the name of Lynell Murray, using Murray's credit card

to pay for the room. At 8:19 p.m., a balance inquiry regarding

Murray's Bank of America checking account and a withdrawal of $80 from

that account were made at an ATM located at a Corona del Mar branch of

the bank. One minute later an additional $60 was withdrawn, leaving a

balance of $4.41.

Later that night, Coffman checked into the Compri

Hotel in the City of Ontario, again using Murray's credit card. Around

midnight on November 13, Coffman and Marlow dined on shrimp and steak

at the Denny's restaurant across the street from the hotel. The two

were seen embracing in the restaurant. Coffman, wearing a skirt and

blouse, did all the ordering and paid for the meal using Murray's

credit card; Marlow, in a three-piece suit, neither smiled nor said

anything to restaurant staff.

Around 3:00 p.m. on November 13, an employee of the

Huntington Beach Inn entered room 307 and found Murray's body. The

cause of death was determined to be ligature strangulation. Murray's

head was in six inches of water in the bathtub; her head and face were

bound with towel strips, and two gags were in and over her mouth. Her

right arm was secured to a towel binding her waist. Her right leg lay

across the toilet, and her left leg rested on the floor in front of

the toilet. Her ankles apparently had been bound with duct tape,

although most of the tape had been removed. Murray's bra, pantyhose

and one earring were missing; evidence suggested she had been raped

and possibly urinated on. She had suffered premortem blunt force

trauma to the head, midsection injuries, bruising of the legs and two

black eyes consistent with having suffered blows before death. A

footprint on a bathmat near the body was consistent with prints made

by boots belonging to Marlow.

After visiting the Koppers' residence on the

morning of November 13, Marlow and Coffman drove to the City of Big

Bear and checked into the Bavarian Lodge. Coffman registered using

Murray's credit card. Further attempts to purchase clothing at a

sporting goods store using Murray's credit card alerted authorities to

defendants' whereabouts and led to their arrest on November 14 while

they walked along a road near Big Bear. When officers seized Coffman's

purse, they found it contained Murray's identification cards and

wallet, an earring matching the lone leaf-shaped earring Murray was

wearing when her body was discovered at the Huntington Beach Inn, a

loaded .22-caliber revolver and .22-caliber ammunition, credit card

receipts bearing Murray's forged signature, and a brown paper bag,

similar to those used at Prime Cleaners, containing coins. A search of

the room defendants had occupied at the Bavarian Lodge yielded

clothing stolen from Prime Cleaners and a gray suit jacket matching

the one Marlow earlier had been seen wearing, with a set of handcuffs

(later determined to be the ones Marlow had taken from Paul Koppers)

in the pocket, identification in the name of James Gregory Marlow, a

ladies' blue wallet and various single earrings. Novis's white Honda

was found parked off a highway near Santa's Village, an amusement park

in San Bernardino County, bearing license plates stolen from a vehicle

parked at the Huntington Beach Inn. Inside a trash can in Santa's

Village, a maintenance worker found a pillowcase with, among other

items, a maroon bra identified as belonging to Murray and laundry

receipts from Prime Cleaners.

b. Marlow's 1979 robberies and 1988 assault

i. Upland robbery

On November 5, 1979, Jeffrey Johnson lived in an

apartment upstairs from sisters Lori and Kathy Liesch on Silverwood

Avenue in Upland. At 6:45 that morning, Johnson answered a knock at

his door. Marlow and one Allen Smallwood, at the time both heroin

addicts, asked Johnson if he worked in construction. When Johnson

answered affirmatively, Smallwood hit him in the face, causing him to

fall to the floor. Entering the apartment, the two men asked where the

drugs were, and Marlow starting beating Johnson with a chain.

Smallwood restrained Johnson while Marlow searched the apartment.

Johnson was then told to put his shoes on and was taken downstairs to

the Liesches' apartment.

Smallwood, holding a knife to Johnson's back, and

Marlow entered the Liesches' apartment, where Lori was still in bed.

Smallwood ordered her to get out of bed and, when she said she had no

clothes on, Marlow attempted to pull the covers off her. After

Smallwood told Marlow to stop, Marlow started searching the apartment

for drugs over Lori's protests that she knew nothing about any drugs.

While searching, Marlow surprised Kathy, who was returning to the

apartment after taking her boyfriend to work. He brought Kathy to the

bedroom, where she, Lori and Johnson were tied up with electrical cord.

Marlow and Smallwood warned them not to contact the police because

they had taken all their identification and would come back for them.

At one point during the ordeal, when Lori would not stop crying after

Smallwood demanded she stop, Marlow grabbed his crotch and told her he

had "something to shut her up." The Liesch sisters each found that a

small amount of cash was missing from their wallets, as well as

Kathy's keys, while Johnson found $180 was missing from his dresser.

ii. Robbery at leather goods store

On November 6, 1979, Joanne Gilligan owned a

leather goods store in Upland. On that day, while she was helping a

customer in the store, Marlow walked in and came to the counter. When

Gilligan asked if she could help him, Marlow told her he had a gun and

she should lie down on the floor. Marlow's hand was in the pocket of

his sweatshirt and it appeared to Gilligan that he could have had a

gun, although she did not actually see one. Gilligan and the customer

she had been helping each got down on the floor, while Marlow removed

money from the register, grabbed a couple of coats and fled. Gilligan

identified Marlow at the preliminary hearing and at the present trial.

iii. Robbery at methadone clinic

On November 20, 1979, Gertrude Smith and Wilson Lee

were working at a methadone clinic in the City of Ontario in San

Bernardino County. At 10:00 a.m. that day, Marlow, armed with a sawed-off

shotgun, and Smallwood, carrying a pistol, entered the clinic. Marlow

ordered clinic employees not to move. Marlow and Smallwood demanded

methadone but were told the drug was locked in the safe. As Marlow

held the shotgun on Smith, Smallwood went down a hallway with Wilson

and confronted an employee, demanding he open the safe where the

methadone was kept. When the employee had difficulty opening the safe,

Marlow urged Smallwood to shoot him in the head. After the safe was

opened, Marlow and Smallwood fled with methadone having a street value

of $10,000.

At the time of his arrest, on November 26, 1979,

Marlow had a bottle containing methadone in his jacket pocket and was

carrying a loaded sawed-off shotgun wrapped in a shirt. He claimed to

have recently purchased the methadone, but refused to identify who

sold it to him or to discuss the clinic robbery.

iv. Assault against jail trustee

On February 17, 1988, Gary Hale, a jail trustee

facing charges of driving under the influence, was bringing breakfast

to other inmates at the San Bernardino County jail. When Marlow

complained, Hale assured him he had been given the same quantity of

potatoes as everyone else. Shortly afterward, Hale noticed Marlow was

pointing a blow gun at him. As Hale walked away, he was hit by a paper

blow dart with a pin at the end. Marlow later bragged to Deputy Carvey

that "It was a lucky shot through the bars."

c. Evidence against Coffman

California Highway Patrol Officer Robert W. Specht

testified that about 4:00 a.m. on April 5, 1986, he detained Doug

Huntley for driving erratically and at high speed. The car, in which

Coffman was a passenger, stopped at an apartment complex in Barstow.

While officers attended to the irate Huntley, Coffman, yelling

obscenities at the officers, ran toward a house carrying her purse.

Specht, who had received a radio report of an earlier incident linked

to Huntley and Coffman, in which Coffman had brandished a gun at

several men who were engaged in an altercation with Huntley at a

7-Eleven store, ordered her to come out of the house with her purse.

When she complied, Sergeant James Lindley of the Barstow Police

Department retrieved a bindle of cocaine or methamphetamine from her

purse; a silver derringer was recovered from the house where Coffman

had hidden it.

Doug Huntley testified that at the 7-Eleven store,

three men had followed him to the parking lot, and one had assaulted

him. After Huntley threw his assailant to the ground, Coffman pulled

the derringer from her purse and held it on the other two men. Huntley

also testified about an incident that had occurred about a year before

the 7-Eleven incident. Huntley was walking down the street after

arguing with Coffman, who drove up beside him and asked him to get in

the car. When he told her he would rather walk home, she drove down

the street, turned around and drove in his direction, coming up on the

sidewalk and forcing him to move out of the way.

2. Marlow's case in mitigation

Marlow's sister, Veronica Koppers, testified she

was born in 1959 and spent her early childhood in rural Stearns,

Kentucky, with Marlow, who was some four years older; her mother,

Doris Hill; her father (Marlow's stepfather), Wendell Hill; and

Doris's mother, Lena Walls. Her parents fought constantly; her father

shot her mother, and she stabbed him seven times.

In 1963, Doris, Lena, Marlow, Veronica, an aunt and

uncle, and their five children all moved to California to get away

from Wendell Hill. They first lived in East Los Angeles and then moved

to El Monte, Azusa and San Dimas. Doris developed a pattern of not

staying with her children on a regular basis, frequently leaving them

for extended periods in Lena's care. Neither Doris nor Lena worked and,

while Lena received Social Security and AFDC payments for the children,

Veronica did not know how Doris supported herself at this time. Doris

customarily had parties, with drinking and marijuana smoking, going on

in her house around the clock. Doris neglected the children, never

taking them to the doctor or dentist and often leaving no food for

them. One Thanksgiving, Veronica recalled, Doris took her and Marlow

to dinner at their uncle's house; Doris said she was going to the

liquor store and did not return for several months. From time to time,

Marlow was sent to stay with his father, Arnold Marlow; he also spent

time in foster homes. Doris enjoyed many types of drugs, became

addicted to heroin, and openly used drugs in front of her children.

She also brought home many different men. Veronica recalled visiting

her mother at the Sybil Brand Institute for Women and at the state

prison in Frontera.

When Doris got out of prison in 1972, she

introduced Veronica to drugs, as she had Marlow and their cousins Pam

and Clel. When Marlow was 15, Veronica saw Doris administer heroin to

him by tying his arm and injecting it. Doris, who was then supporting

herself with prostitution and stealing from her "tricks," also taught

Veronica how to burglarize houses.

Ray Saldivar testified that he met Doris in 1964,

when she bought drugs from him. As of the time of trial, Saldivar had

conquered his drug habit and was working as a tree trimmer. In 1965,

Saldivar moved in with Doris and, after living there for several days,

first discovered that Doris had children, despite the fact he had

visited her house numerous times before moving in. She was not a

loving mother, frequently having to be reminded to feed the children.

Marlow was constantly afraid his mother was going to leave him, to the

point that he sometimes slept on the floor next to her bed. In their

household, people came and went all day long to buy drugs. In

Saldivar's opinion, Marlow was an "innocent child" who "didn't [ask]

to grow up" in "that abnormal home" and "grew up around nothing but

dope fiends all his life."

Lillian Zamorano testified that she met Doris in

the mid-1960's at a bar in Pico Rivera where the two women came to

spend a good part of their time. They became good friends, and Doris

eventually moved into Zamorano's house. Doris did not mention to

Zamorano that she had children until at least six months after they

met. Zamorano never saw Doris display any affection toward her

children. Zamorano's daughter, Rosemary Patino, met Marlow on

Christmas 1966 and remembered him as a "good," "normal," "playful"

child. On that occasion, she testified, they expected a family holiday,

but Doris and Lillian left to go to a bar despite Marlow's crying and

pleading with Doris to stay.

Doris died in a fire in 1975.

Sue Warman, formerly the wife of Arnold Marlow,

testified she first met Marlow when he was six and a half years old

and was sent to live with his father. Marlow's "mouth had sores all

around it and his teeth were rotten." Warman took Marlow to the

dentist and the doctor, bought him new clothes and enrolled him in

school. Although initially positive about Marlow's arrival, Arnold

soon began giving Marlow frequent "whippings" "if everything wasn't

done . . . just right." In Warman's view, Marlow was "a lonely, lost

little boy wanting somebody to love him." Marlow stayed with his

father and Warman for about three months, until Doris came to his

school, unannounced, and took him away. Because Doris had legal

custody of Marlow, Warman was told nothing could be done. Warman did

not see Marlow again for another seven years. In 1969, California

welfare officials contacted Arnold, asking if he could take care of

Marlow. At 13, Marlow appeared in better condition than the first time

Warman had seen him, but he "still looked like that little, lost,

lonely boy." Marlow got along well with his half siblings, and Warman

never had any problems with him. Arnold, however, continued to beat

his children, including Marlow. After about a year, Warman-tired of

Arnold's drinking and abusive behavior-made plans to leave him.

Knowing she would not get custody, she took Marlow to a foster home so

that he would not have to stay with his father. Warman asked the jury

to spare his life, commenting that his death "won't bring those people

back. And Greg never had a chance from the day he was born either. And

I love him. I always loved him."

Allen Smallwood, who at the time of trial was

serving a sentence at Folsom State Prison for a series of robberies,

testified that he met Marlow at a party when Marlow was 23 years old;

Smallwood was 35 and had already been convicted of two robberies and

two escapes. Smallwood was then a heroin addict with a $700 per day

habit; Marlow had a somewhat lesser habit. Smallwood testified he

recruited Marlow, who was undergoing heroin withdrawal, to rob a man

named Johnson, who Smallwood had heard was a police informant.

Smallwood and Marlow robbed Johnson of several thousand dollars in

cash and about six ounces of cocaine. Smallwood denied that Marlow had

a chain during the robbery. Later, Smallwood traded some of the

cocaine for heroin and some for weapons he planned to use in robbing

the methadone clinic, for which effort he again recruited Marlow, who

was again going through withdrawal. Smallwood testified he did not

think Marlow would have committed those robberies without his

importunings. Smallwood had to "show him the ropes," as Marlow, whose

criminal experience was limited to "stuff like" "petty shoplifting,"

was "kind of naïve."

Clinical psychologist George Askenasy testified

that in 1975, when he conducted a psychological examination of Marlow

for the California Youth Authority, he had found him "a pathetic young

man with a chaotic life history," whose father showed no interest in

him and whose mother exhibited a "smothering" "possessiveness" toward

him. Marlow, the witness stated, was "caught in an approach-avoidance

conflict with many guilt feelings about his relationship with his

mother," "anxious, feeling of inadequacy, sexual confusion, [and]

unmet dependency needs . . . ."

3. Coffman's case in mitigation

Katherine Davis, Marlow's former wife, testified

regarding Marlow's violence and jealousy and its emotional and

physical effects on her. Her testimony is summarized below in

connection with a related claim of error (see post, at p. 96). Marlene

Boggs, Davis's mother, confirmed much of her daughter's testimony and

described observing her daughter's scars and bruises, as well as a 75-pound

weight loss and hair loss, during Davis's relationship with Marlow.

Coffman's former employers testified she was a good worker when

employed as a waitress and bartender in Arizona.

Carol Maender, Coffman's mother, testified about

the marital, financial and other difficulties she encountered in

raising Coffman and sons Robbie and Jeff, the latter of whom was given

up for adoption. As an infant, Coffman had suffered from a painful

double inguinal hernia that required surgical repair while she was

still in early infancy.

Maender testified to a lack of closeness with

Coffman, progressing to irritability and aggression on Coffman's part

toward her mother. Coffman bonded well, however, with her stepfather,

Bill Maender. Coffman went through Catholic grammar school and public

junior high school without major difficulty, but once in high school

she encountered problems with grades, truancy and drugs. At one point,

she ran away and stayed at the home of her boyfriend, Ron Coffman, for

a couple of months; the Maenders did not know where she was. Coffman

returned to her own home when she discovered she was pregnant. Their

son was born after Coffman graduated from high school; the couple

married and, with the baby, moved into a bungalow on Ron's parents'

property. The marriage was not a happy one; Ron was mean, abused her

physically and cheated on her with other women. Eventually Coffman

left him, moving into an apartment and working while Ron's mother took

care of the baby. Then Coffman left Missouri for California, planning

ultimately to have her son with her, but Ron's parents obtained

custody of the child. Bill Maender, Coffman's stepfather, testified

Coffman did not abandon her son when she moved west.

Clinical psychologist Craig Rath, Ph.D., examined

Coffman and opined that Coffman's relationship with Marlow was

precipitated by impaired bonding in her early life. He felt she was

not malingering and discounted the possibility that she suffered from

antisocial personality disorder catalyzed by Marlow.

4. Prosecution's rebuttal

Sergeant Richard Hooper of the Huntington Beach

Police Department testified that Chuck Coffman, Ron Coffman's father,

told him Cynthia Coffman's personality was aggressive when he knew her

in St. Louis.

II. Pretrial and Jury Selection Issues

A. Denial of Severance Motion

Before and at various points during trial, each

defendant unsuccessfully moved for severance. Defendants now contend

the denial of their motions requires reversal of the judgment.

Section 1098 expresses a legislative preference for

joint trials. The statute provides in pertinent part: "When two or

more defendants are jointly charged with any public offense, whether

felony or misdemeanor, they must be tried jointly, unless the court

order[s] separate trials." (See People v. Boyde (1988)

46 Cal.3d 212, 231, affd. on other

grounds sub nom. Boyde v. California (1990) 494 U.S. 370 [acknowledging

legislative preference].) Joint trials are favored because they "promote

economy and efficiency" and " `serve the interests of justice by

avoiding the scandal and inequity of inconsistent verdicts.' " (Zafiro

v. United States (1993)

506 U.S. 534, 537, 539.) When defendants

are charged with having committed "common crimes involving common

events and victims," as here, the court is presented with a "classic

case" for a joint trial. (People v. Keenan (1988)

46 Cal.3d 478, 499-500.)

The court's discretion in ruling on a severance

motion is guided by the nonexclusive factors enumerated in People v.

Massie (1967)

66 Cal.2d 899, 917, such that severance

may be appropriate "in the face of an incriminating confession,

prejudicial association with co-defendants, likely confusion resulting

from evidence on multiple counts, conflicting defenses, or the

possibility that at a separate trial a co-defendant would give

exonerating testimony." Another helpful mode of analysis of severance

claims appears in Zafiro v. United States, supra, 506 U.S. 534. There,

the high court, ruling on a claim of improper denial of severance

under rule 14 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, observed

that severance may be called for when "there is a serious risk that a

joint trial would compromise a specific trial right of one of the

defendants, or prevent the jury from making a reliable judgment about

guilt or innocence." (Zafiro, supra, at p. 539; see Fed. Rules

Crim.Proc., rule 14, 18 U.S.C.) The high court noted that less drastic

measures than severance, such as limiting instructions, often will

suffice to cure any risk of prejudice. (Zafiro, supra, at p. 539.)

A court's denial of a motion for severance is

reviewed for abuse of discretion, judged on the facts as they appeared

at the time of the ruling. (People v. Hardy (1992)

2 Cal.4th 86, 167.) Even if a trial court

abuses its discretion in failing to grant severance, reversal is

required only upon a showing that, to a reasonable probability, the

defendant would have received a more favorable result in a separate

trial. (People v. Keenan, supra, 46 Cal.3d at p. 503.)

Coffman argues that several factors dictated

severance of her trial from Marlow's: the antagonistic nature of their

defenses, the expected introduction of Marlow's extra-judicial

statements implicating her in the offenses (see People v. Aranda

(1965)

63 Cal.2d 518, 526-527), and the risk of

prejudicial association with the assertedly more culpable Marlow.

Citing, inter alia, Johnson v. Mississippi (1988) 486 U.S. 578,

Coffman also relies on the need for heightened reliability of the

determination of guilt and penalty in a capital case. Marlow, in turn,

relies on the antagonistic nature of Coffman's defense and the

resultant admission of much evidence inadmissible on any theory as to

him but relevant to Coffman's state of mind. As will appear, we find

no abuse of discretion in the denial of defendants' severance motions.

In People v. Hardy, supra, 2 Cal.4th at page 168,

we said: "Although there was some evidence before the trial court that

defendants would present different and possibly conflicting defenses,

a joint trial under such conditions is not necessarily unfair. [Citation.]

`Although several California decisions have stated that the existence

of conflicting defenses may compel severance of co-defendants' trials,

none has found an abuse of discretion or reversed a conviction on this

basis.' [Citation.] If the fact of conflicting or antagonistic

defenses alone required separate trials, it would negate the

legislative preference for joint trials and separate trials `would

appear to be mandatory in almost every case.' " We went on to observe

that "although it appears no California case has discussed at length

what constitutes an `antagonistic defense,' the federal courts have

almost uniformly construed that doctrine very narrowly. Thus, `[a]ntagonistic

defenses do not per se require severance, even if the defendants are

hostile or attempt to cast the blame on each other.' [Citation.] `Rather,

to obtain severance on the ground of conflicting defenses, it must be

demonstrated that the conflict is so prejudicial that [the] defenses

are irreconcilable, and the jury will unjustifiably infer that this

conflict alone demonstrates that both are guilty." (Ibid., last

italics added.) When, however, there exists sufficient independent

evidence against the moving defendant, it is not the conflict alone

that demonstrates his or her guilt, and antagonistic defenses do not

compel severance. (Ex parte Hardy (Ala. 2000) 804 So.2d 298, 305.)

In this case, although Coffman's defense centered

on the effort to depict Marlow as a vicious and violent man, and some

evidence that would have been inadmissible in a separate guilt trial

for Marlow occupied a portion of their joint trial, the prosecution

presented abundant independent evidence establishing both defendants'

guilt. Such evidence showed that Coffman and Marlow, with Novis, came

to the Drinkhouse residence around 7:30 on the evening of Novis's

disappearance; Marlow indicated to Drinkhouse that they needed to get

Novis's PIN in order to rob her. When Drinkhouse asked Marlow if he

were crazy and complained about their bringing Novis to his house,

Marlow told him not to worry, saying, "How is she going to talk to

anybody if she's under a pile of rocks?" When Veronica Koppers arrived

at the Drinkhouse residence a while later, Marlow told her he had

someone there and "not to freak out on him." Coffman appeared to be

going along willingly with Marlow's actions and did not ask for

Veronica's help to escape Marlow. Marlow took Novis into the shower,

and both left the house with wet hair, along with Coffman. Novis had

duct tape over her mouth. Novis's apartment later was found to have

been entered and her typewriter and answering machine stolen. Marlow

and Coffman traded the answering machine for drugs, and Coffman, using

Novis's identification, pawned the typewriter. The day after Novis's

disappearance, Marlow, Coffman and Veronica Koppers returned to Paul

Koppers's home; Marlow asked him if he could get any "cold," i.e.,

nontraceable, license plates for the car. Three days later, near a

trash receptacle located behind a Taco Bell restaurant in Laguna Beach,

where Coffman previously had been seen, a bag was found containing

identification and other items belonging to Coffman, Marlow and Novis.

Novis's car was found on November 14, 1986, abandoned on a dirt road

south of Santa's Village near where Marlow and Coffman were seen

walking on Big Bear Boulevard. Coffman's fingerprints were found on

the license plate, hood and ashtray of the car; one print on the hood