Classes had been going for a week at the Edgar Allen Poe elementary school in well-to-do south Houston. But the principal, Mrs. R. E. Doty, took it as a matter of course when a slight, pleasant man in sports shirt and slacks walked into the school lobby at 10 o'clock one morning last week and announced that he wanted to register his sandy-haired, seven-year-old, Dusty, in second grade.

She was only mildly surprised when Paul Harold Orgeron, 47, said sheepishly that he had just come to town and did not know his address, did not even have Dusty's report card or health certificate. He inquired persistently but politely about the location of the second-grade classrooms, then left quietly, promising to come back next day with the documents.

A few minutes later, Paul Orgeron and Dusty walked together across the big, asphalt-topped playground behind the school, where 50 second-grade children, under the watchful eyes of a teacher, were playing "spat-'em." Orgeron carried a newspaper-wrapped bundle and a suitcase. Dusty carried another suitcase. "Teacher!" called Orgeron. He walked up to Second-Grade Teacher Patricia Johnson and said: "Call all your children up here!"

The Doorbell. At first, Patricia Johnson thought that Orgeron was carrying "something horribly obscene in that suitcase." Wary, she tried to send him away. "He started babbling about the will of God, and he talked about power," Teacher Johnson said later. "I shouted 'Go back' to the children and sent a little child to get Mrs. Doty. He was talking very rapidly now. 'Well, read this, and don't get excited,' he said."

She began to read the painful scrawl: "Please do not get excite over this order I'm giving you. In this suitcase you see in my hand is fill to the top with high explosive. I mean high high . . . I do not believe I can kill and not kill what is around me, and I mean my son will go too . . . Please do not make me push this button that all I have to do . . ."

"Then," says Miss Johnson, "he showed me the bottom of the suitcase. On it was a doorbell, just a regular little button, and he said when he set the suitcase on the ground it would press the button and it would blow up. He put the suitcase down with one end on the ground and the other end on the tip of his shoe so the button wouldn't touch the ground. I told the children to get back again. I sent a second runner into the school. I thought maybe the first had been stopped in the hall for running."

Minutes later a corporal's guard of teachers came toward Orgeron: Miss Johnson backed off to lead most of her children toward the building. In the patio she saw School Custodian James Montgomery. "Mr. Montgomery," she said, "that man has dynamite out there." Orgeron shouted: "Stay away from here or I'll blow you to pieces!" At his side, still wordless, was Dusty. The rest of the schoolchildren had stopped their games and were watching.

Custodian Montgomery lunged for Orgeron. Orgeron slipped his toe out. The suitcase fell.

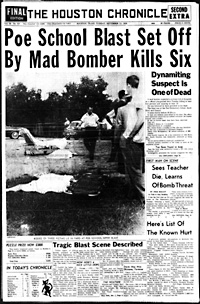

The Children. The shattering blast crunched through the yard with a roar. In that instant came the smell of powder and burning flesh. The explosion tore to bits the bodies of Dusty and two other children, a teacher, Custodian Montgomery and Paul Orgeron himself—six dead in all. Body fragments flew across the street to the roof of a two-story apartment house. Orgeron's left hand—all that could be identified of the man—landed in a hedge 50 ft. away.

Principal Doty lay injured on the ground, and 17 children, strewn near by, screamed in pain. A little boy writhed naked, his foot nearly blown off. "That mean old man!" he sobbed. "That mean old man! Will somebody get him? Will I need a crutch for my foot? Why did he have to do it?"

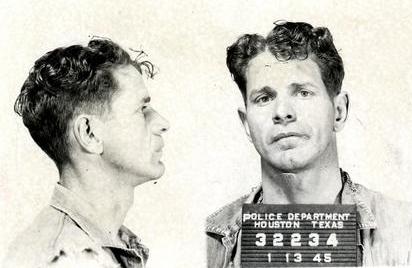

Policemen asked the same question, soon discovered that Paul Harold Orgeron was an ex-convict and sometime tile layer, syphilitic, illiterate, and obsessed by dark fantasies of power and gods. He had been married, divorced, had remarried the same woman and been divorced again. He had cowed his daughter Zelda with abuse and with ugly accusations of promiscuity. He had fathered a son by his stepdaughter Betty Jean, who had run away in fear and shame. And in all the world—in some tormented way—he loved only the memory of Betty Jean and their son Dusty.

Poe Elementary School, Houston, Texas

Tuesday, September 15, 1959

About 8:30 this morning, 49-year-old tile contractor Paul Harold Orgeron went to his mother's house to pick up his son, Dusty, so that he could enroll him at Poe Elementary School. Paul helped wash and dress his son before telling Dusty to get some toys to entertain himself as he would be out of the house most of the day. Paul took Dusty to the school's principal's office, Mrs. R. E. Doty, while carrying a briefcase. Paul said he would like to enroll his son in the second grade and she said he would need to register him first. Paul and Dusty, who had just turned seven on Saturday, left the office then and went out to the playground. Paul handed two notes to second grade teacher Miss Johnston. The notes were written illegibly and incoherently. One note read: "Please do not get excited over this order I'm giving you. In this suitcase you see in my hand is fill to the top with high explosives. I mean high high. An all I want is my wife Betty Orgeron who is the mother of son Dusty Paul Orgeron. I want to return my son to her. Their answer to this is she is over 16 so that (is) that. Please believe me when I say I gave 2 more cases, that are set to go off at two times. I do not believe I can be kill (sic) and not kill what is around me, and I mean my son will go to. Do as I say and no one will get hurt. Please. P. H. Orgeron. Do not get the police department yet. I'll tell you when." Paul then triggered the gelex in the briefcase by firing a single shot from a .32 pistol with a string attached to the trigger. Gelex is more powerful than dynamite and is used in commercial work on oil well perforations. The explosion killed Paul, Dusty, William Hawes Jr., John Cecil Fitch Jr., teacher Jennie Kolter and the school custodian James Arlie Montgomery. Mrs. Doty had her clothes torn off from the blast and the grisly scene even affected the news reporters as they came to the site. Seventeen other children were wounded. Earl and Robert Taylor needed their legs amputated to survive. Paul had a been convicted twice in Louisiana and once in Texas and for burglary and theft.

THOSE WHO DIED:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE INJURED:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Austin American-Statesman: Tots, Adults Killed in School Bombing

I Have Got to Get to the Children

Texas Rangers Dispatch

Though Rangers have a reputation of working alone, this is seldom the case. A Ranger's duty is to assist other law enforcement officers. Newspaper articles commonly go like this: "Local officers, assisted by the Texas Rangers..."

Most, if not all, Texas Rangers will tell you that the cases that really get to them are the ones that involve children. In the following case, Ranger Ed Gooding was called to investigate a tragic bombing at a local elementary school.

The following is Ranger Gooding’s account of the Edgar Allen Poe Elementary School tragedy.

Tuesday, September 15, 1959, is a black-letter date in Houston. The sound of the explosion that rocked Edgar Allen Poe Elementary School at about ten o’clock that morning had not been heard in Texas since the terrible New London School explosion in which more than 300 had died eighteen years before. Poe Elementary School, located near the campus of Rice University, had become the target of a madman.

Journalists today would lead us to believe that school terrorism is a modern-day experience. I’ve heard people say that Charles Whitman started it all when he climbed into the Tower at the University of Texas in Austin and started killing people on August 1, 1966. Well, Whitman wasn’t the first. At Poe Elementary, Paul Harold Orgeron murdered an innocent teacher, a custodian, and three seven-year-old boys—including his own son—in 1959. I suspect that there were other acts of cowardly mayhem even before this.

Poe Elementary School principal Ruth Doty was walking down the hall when she met a shabby, middle-aged man and a young boy. (Other witnesses said Orgeron was neatly dressed. I suspect that the shabbily dressed description may have been slanted after the fact.) Paul Orgeron told Mrs. Doty that he wanted to enroll his seven-year-old son, Dusty Paul, in school. She said that was fine. If they would follow her, she would take them to the school office to fill out the necessary paperwork. At the office, Mrs. Doty asked Juanita Weidner, a secretary, to give Orgeron the necessary enrollment forms.

Ms. Weidner asked Orgeron where he and his son had moved from, what school his son had been attending, where they were currently living, and what he did for a living. She wasn’t asking officially; most of that information would be covered on the enrollment papers. She was just making conversation. Not surprisingly, she became suspicious when he couldn’t remember the name of the school his son hadbeen attending or the name of the town. All he could remember was that it was in New Mexico. As for their current address, he couldn’t remember that either. They had been in Houston only a few days and, until the previous Monday, they had been living in a boarding house at 2720 LaBranch Street. The best he could recall, the street they had moved to was Bissonnett Street. However, he definitely remembered that he was a tile contractor by trade.

Parts of Orgeron’s story later turned out to be true, sort of. When the address was checked with the owners of the boarding house on LaBranch Street, the E. C. Adamses, they identified the pictures of Orgeron and his son as former boarders who had lived at their house from September 10 until September 12. They said the man and boy were very quiet and never made any trouble. But they didn’t know the man as Paul Orgeron: he had given his name as Bob Silver (we never did find out where thatname came from). As for being a tile contractor, this was also true. But he was also a convicted safecracker.

Ms. Weidner told Orgeron that she was sorry, but since he didn’t have Dusty’s birth or health certificates with him, she could not enroll Dusty. Taking the enrollment form, he said they would return the next day with the needed certificates. Later, Ms. Weidner reported that Orgeron had talked rather loudly and fast, but that he appeared neither angry nor upset.

It was now almost ten o’clock and near the end of the period. Students from five first- and second-grade classes were getting ready to return to their rooms from their recess on the schoolyard. Just as Patricia Johnston, a ten-year teacher (three of them at Poe), was preparing to take her second-grade class into the building, she was approached by Orgeron and Dusty. Orgeron was carrying a brown, abric-covered suitcase. The small, freckle-faced boy also carried a similar small bag.

Orgeron stopped in front of Ms. Johnston, handed her two pieces of paper, and said, “Teacher, read these.” Ms. Johnston said that the penmanship was so bad that the notes were almost unreadable. While she studied them, Orgeron kept mumbling something about the will of God and “ . . . having power in a suitcase.” All the while, he was moving the suitcase up and down. She noticed what appeared to be a doorbell-type button on the bottom of the bag.

Orgeron kept urging Ms. Johnston to gather all the children around them in a circle. She wasn’t having any part of that until he could explain to her why he wanted the children and what he had in the suitcase. Still unable to make out what the notes said, Ms. Johnston was by now thoroughly alarmed. She was worried that the children that had joined her might be in terrible danger, and she wanted to getthem as far away from this strange man as possible. She told two of the children to go find Mrs. Doty and James Montgomery, the school custodian. The rest she told to immediately go back inside the building.

Two other teachers, Julia Whatley and Jennie Kolter, were walking out the door when they saw their colleague talking to the strange man and small boy. It was the school policy not to let a teacher stand by herself with suspicious-looking people. They were already heading toward her when they saw Ms. Johnston signaling them to join her. Ms. Johnston handed the note to Ms. Kolter. Meanwhile, Orgeron continued rambling about “power in the suitcase” and that he had to “get to the children.”

A few moments later, Ruth Doty and James Montgomery joined the group. No longer being needed, Ms. Whatley returned to her students and started moving them into the school building, with the girls leadingthe way. Pat Johnston also left the group and started toward her students to also get them into the building.

Mrs. Doty told Orgeron he would have to leave the school grounds immediately. Paying no attention to the principal, Orgeron kept rambling and repeating, “I have to follow the children to the second grade.” He also kept waving the suitcase around.

That was the last thing any of them remembered. Suddenly, there was a tremendous explosion and six people were dead: Jennie Kolter, teacher; James Montgomery, school custodian; seven-year-old students Billy Hawes, Jr. and John Fitch, Jr.; and Paul Orgeron and his seven-year-old son Dusty.

The only word to describe Edgar Allen Poe Elementary School when I arrived is bedlam—absolute bedlam. Parents were swarming the school grounds, frantically searching for their children. Law nforcement officers were fighting a losing battle trying to keep order and, of course, the curiosity seekers were out in full force.

I joined officers from the Houston Police Department, the Harris County Sheriff’s Department, and the FBI. The devastation was unbelievable. The blast had occurred directly under a maple tree. If you had gone by the looks of the tree, you would have thought it was the dead of winter: there was not a leaf to be found anywhere on it. All that hung from the stripped branches were bits of human flesh and a few shreds of clothing. There was a hole six inches deep at the spot of the asphalted playground where Orgeron had detonated the bomb.

Several bodies were lying on the playground, but one I remember in particular. One of the boys was totally nude. The force of the explosion had ripped every piece of clothing off the poor child.Soon, we tentatively identified the bomber. Juanita Weidner said he had given his name as John Orgeron when he and his son had been in her office earlier. There was still one big problem: we weren’t sure that he was dead. There wasn’t a body, at least not one that was identifiable, and we were afraid that the bomber was still on the school grounds with another explosive.

There is only one way to cope with violent death when you have seen as much of it as I have: harden yourself to it and do not under any circumstances let yourself become emotionally involved. Sometimes you even laugh about it. It’s not funny and you’re not belittling the horror and pain, but that’s one of the ways you learn to cope. However, no matter how much you steel yourself, you never get to a point where innocent children thrown into the path of violence doesn’t unsettle you. Orgeron’s son and the other slaughtered children bothered me more than anything I had seen since the time we had lobbedthe hand grenades into the cellar back in Europe and killed not only two SS soldiers, but a whole family. Like that incident, this would bother me for a long time. At that moment, however, I had to put that aside and do what all the other officers on the campus were doing: our jobs. That was easier said than done. I really felt sorry for those officers who had not seen as much death as I had during the war in Europe. They were having a really difficult time with it.

We evacuated the school to determine that there was not another bomb in the building. Then we asked all the children and teachers to return to their classrooms so the teachers could conduct a roll call. Except for the dead and wounded, everyone else was soon accounted for.

I have to say right here that I have seen hardened combat soldiers not act as bravely as these teachers and children did. It was really incredible. There was one little nine-year-old boy, Costa Kaldis, that I specially remember. He would have been awarded a medal for extraordinary bravery if he had been in the service. The school had supposedly been cleared of all the children when young Kaldis heard a child crying. A small polio victim had been unable to leave the building with the others and had inadvertently been left behind. Without a second’s hesitation, little nine-year-old Kaldis ran back into the room and carried his schoolmate to safety. Remember, no one knew at that time whether or not there was another bomb still in the school. I have often wondered whatever happened to Costa Kaldis. He was as brave as anyone I’ve ever known.

Once everyone was accounted for, we started a search of the area around the blast, looking for anything and everything: bodies, wounded, or any clues as to what had happened and why. I was walking down a row of hedges along North Boulevard when I saw a man’s left hand hanging on one thehedge’s branches about sixty feet from the spot of the explosion.

Lloyd Frazier, assistant chief deputy of the Harris County Sheriff’s Department, was an explosive and fingerprint expert and a better-than-average crime-scene chemist. Lloyd was a real student of his profession and could do just about anything concerning law enforcement. He took the hand for fingerprint identification, and we soon had a positive identification. We didn’t have to worry about Orgeron setting off any more bombs.

Orgeron, 47, had a long police record, dating back to 1930. He had served two terms in Texas prisons and one in Louisiana. He was an old-time safe burglar, which accounted for his knowledge of dynamite.

Orgeron’s left hand wasn’t his only body part we found before completing our search of the area. His severed foot was found near the bomb site. The following day, the owner of a two-story building acrossthe street from the school noticed a terrible smell coming from his roof. He found Orgeron’s missing right shoulder and arm. Another man who also lived across the street from the school found a piece of flesh in his backyard.

We also found the notes Orgeron had given to Pat Johnson:

Please do not get excite over this order I’m giving you. In this suitcase you see in my hand is fill to the top with high explosive. I mean high high. Please believe me when I say I have 2 more (illegible) that are set to go off at two times. I do not believe I can kill and not kill what is around me, an I mean my son will go. Do as I say an no one will get hurt. Please.

P. H. Orgeron

Do not get the Police department yet, I’ll tell you when.---

Please do not get excite over this order I’m giving you. In this suitcase you see in my hand it fill to the top with high explosive. Please do not make me push this button that all I have to do. And also have two 2 more cases (illegible) high explosive that are set to go off at a certain time at three different places so it will more harm to kill me, so do as I say and no one will get hurt. An I would like to talk about god while waiting for my wife.

---

Continued Search

Sheriff’s deputies and I continued to search the school grounds while several Houston police officers started looking for Orgeron’s vehicle. They found his 1958 green and ivory Chevrolet station wagon parked along North Street across from the school. Several sticks of dynamite were under the hood, ying on the upper side of the wheel well and a box of dynamite fuses was located in the car’s glove box. Coils of wire, batteries, and BB-gun pellets were found in the backseat. In the trunk, they found a child’s cowboy book, another book titled Children At Play, a toy airplane, a toy submachine gun, and a toy six-shooter.

Also found at the blast scene was a sales ticket in the amount of $41.94 for blasting caps, fuses, and one hundred and fifty sticks (approximately fifty pounds) of dynamite from the Bond Gunderson Company in Grants, New Mexico. This gave us a whole new problem. As big as the explosion was, it wasn’t nearly as big as it would have been if Orgeron had used one hundred and fifty sticks of dynamite. Where was the rest of the dynamite? We never did find it. I suspect Orgeron passed the dynamite on to some safecrackers. Just like today, there are a lot of nuts in this old world. The dust hadn’t even settled before sickos started calling, claiming they had planted bombs in other schools all around Houston. Finally, the National Guard was called out and placed at schools throughout the area. One school in San Antonio even received a threat from what turned out to be three teenagers. Thankfully, they all proved to be pranks. Some people have a real sick sense of humor.

After completing our crime scene investigation, we bagged as many body parts as we could find and sent them to a local Houston funeral home. We notified all of Orgeron’s next-of-kin possible, many of whom lived in the Houston area, that they could claim the bodies. Dusty was terribly mutilated, and the only way a relative could make a positive identification of the boy was from a small scar under his chin. As far as I know, none of the relatives ever claimed Orgeron. We discovered that Orgeron’s former wife Hazel lived in Houston. It turned out that they had been married and divorced twice. She said she had tried to make a go of it both times, but since he liked to use her for a punching bag, it had been impossible. The last time she had talked to him was at Dusty’s seventh birthday party the previous Saturday, at the home of his maternal grandmother Maude Tatum. He claimed that he had found God, had no malice for anyone, and was a changed man.

Continuing, Hazel said that Paul and Dusty had been devoted to one another and that they had been inseparable ever since the divorce in July of 1958. She said they wandered from place to place, never staying in any one place for long. All she knew about their travels was that they had been in Altus, Oklahoma, shortly before returning to Houston.

Upon investigating, we

discovered that in July and August, Orgeron

had worked as a tile contractor for James

Scarborough in Altus. During the whole

period, it appears that Orgeron and Dusty

had slept either in the back of their

station wagon or in a tent. When questioned,

Scarborough said that for some reason that

he never gave, Orgeron had insisted that he

had to leave Altus no later than August 25.

He also didn’t say where he had to go or why.

He had, in fact, left a few days before

August 25. We know he was in Grants, New

Mexico, on August 25, when he bought the

dynamite from the Bond Gunderson Company. We

were never able to say for certain where the

Orgerons were between August 25 and

September 10, when they moved briefly into

the Adams’ boarding house at 2720 LaBranch

Street in Houston.