714 F.2d 365

Ronald Clark

O'Bryan, Petitioner-Appellant,

v.

W.J. Estelle, Jr.,

Director, Texas Department of

Corrections, Respondent- Appellee.

No. 82-2422

Federal Circuits, 5th Cir.

August

30, 1983

Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Southern District of

Texas.

Before RANDALL and

HIGGINBOTHAM, Circuit Judges, and

BUCHMEYER,

District Judge.

RANDALL, Circuit

Judge:

Ronald Clark O'Bryan

was convicted of the murder of his own

child in a Texas state court in 1974 and

sentenced to die. On appeal from the

federal district court's denial of

habeas corpus relief, 28 U.S.C. 2254

(1976), the defendant contends:

(1) that the

exclusion of three jurors who expressed

conscientious objections to the death

penalty violated the rule of Witherspoon

v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510, 88 S.Ct.

1770, 20 L.Ed.2d 776 (1968);

(2) that the Texas

death penalty procedure is

unconstitutional because it does not

provide for jury instructions concerning

mitigating circumstances;

(3) that the

defendant's constitutional rights were

violated when the trial court permitted

the prosecutor to comment on defense

counsel's failure to ask defense

witnesses certain questions about the

defendant's reputation; and

(4) that the trial

court's refusal to instruct the jury on

the law governing parole as it relates

to persons sentenced to life

imprisonment violated the defendant's

due process rights.

While we are

compelled to recognize that O'Bryan has

raised a serious challenge to the

exclusion of two of the three jurors

under Witherspoon, we conclude that the

district court's denial of habeas corpus

relief should be affirmed.

I. FACTUAL AND

PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND.

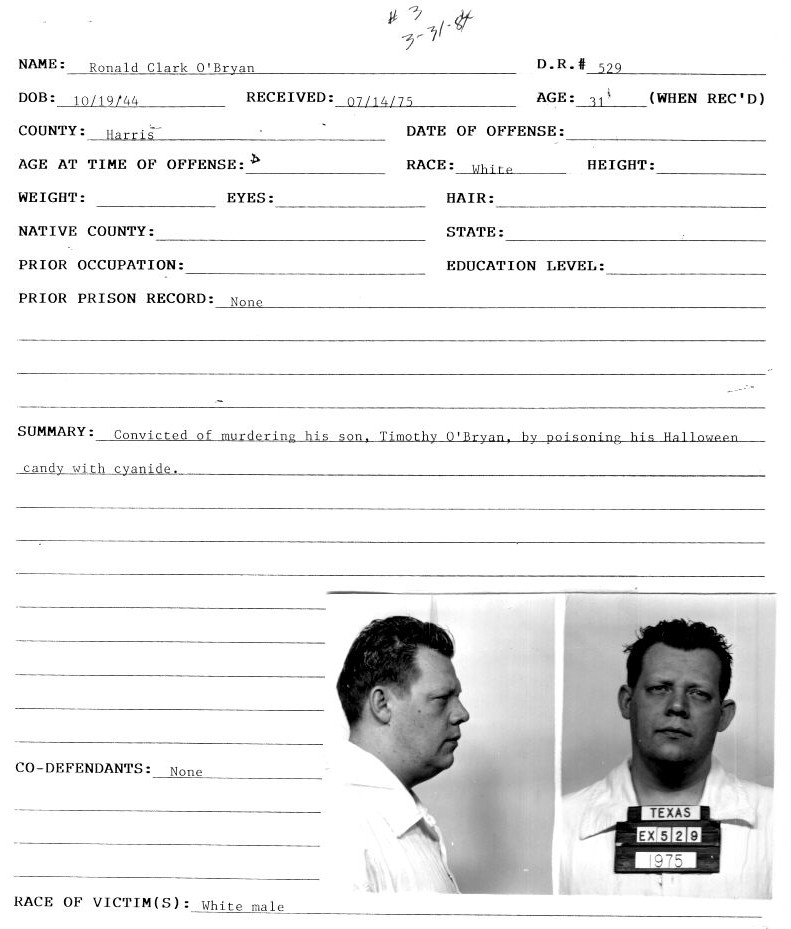

O'Bryan was convicted

of murdering his eight-year-old son,

Timothy, for remuneration or the promise

thereof, namely, the proceeds from a

number of life insurance policies on

Timothy's life. See Tex.Penal Code Ann.

§ 19.03(a)(3) (Vernon 1974).

The facts of this case as adduced at

trial are set forth in detail in the

Texas Court of Criminal Appeals'

disposition of O'Bryan's direct appeal.

O'Bryan v. State, 591 S.W.2d 464 (Tex.Cr.App.1979)

(en banc), cert. denied,

446 U.S. 988 , 100 S.Ct. 2975, 64

L.Ed.2d 846 (1980). We have

summarized them briefly here.

The record reflects

that O'Bryan, who worked as an optician

at Texas State Optical Company, had

serious financial problems. The family

was delinquent on a number of loans and

had been forced to sell their home to

meet their most pressing obligations.

O'Bryan discussed his financial burdens

with friends and acquaintances,

informing some of them that he expected

to receive some money by the end of the

year.

Despite his financial

difficulties, O'Bryan substantially

increased the life insurance coverage on

his two children, Timothy and Elizabeth

Lane, during 1974. By mid-October there

was $30,000 worth of coverage on each

child, while the coverage on O'Bryan and

his wife was minimal.

In August, 1974,

O'Bryan tried unsuccessfully to obtain

cyanide where he worked. In September,

he called a friend who worked at Arco

Chemical Company, and the two discussed

the varieties and availability of

cyanide. O'Bryan continued to discuss

cyanide among his fellow employees at

Texas State Optical.

Shortly before

Halloween, O'Bryan appeared at Curtin

Matheson Scientific Company, a chemical

outlet in Houston. When he discovered

that the company had cyanide available

only in large quantities, O'Bryan asked

the salesperson where he could obtain a

smaller amount.

On Halloween,

Thursday, October 31, 1974, the O'Bryan

family dined at the home of the Bates

family. The children of both families

had planned to go "trick or treating"

together in the Bates' neighborhood. The

defendant and Mr. Bates accompanied

O'Bryan's children and Bates' son on the

Halloween outing.

When the party

arrived at the Melvins' home, the lights

were out, but O'Bryan and the children

went up to the home anyway. When no one

answered the door, the children went on

to the next house; O'Bryan remained

behind for about thirty seconds. He then

ran up to the children, "switching" at

least two "giant pixy styx" in the air

and exclaiming that "rich neighbors"

were handing out expensive treats.

O'Bryan offered to carry the pixy styx

for the children. Back at the Bates'

home, O'Bryan distributed the pixy styx

to his and Bates' two children, and gave

a fifth stick to a boy who came to "trick

or treat" at the door.

After the Halloween

festivities had been completed, O'Bryan

took his children home, while his wife

went to visit a friend. O'Bryan informed

the children that they could each have

one piece of candy before going to bed;

Timothy chose the pixy stick. The boy

had trouble getting the candy out of the

tube, so O'Bryan rolled the stick in his

hand to loosen the candy for his son.

When Timothy complained that the candy

had a bitter taste, O'Bryan gave him

some Kool-Aid to wash it down.

Timothy immediately

became ill and ran to the bathroom,

where he started vomiting. When Timothy

became sicker and went into convulsions,

O'Bryan summoned an ambulance. Timothy

died within an hour after he arrived at

the hospital. Cyanide was found in

fluids aspirated from his stomach and in

his blood. The quantity of cyanide in

the blood was well above the fatal human

dose.

There was conflicting

testimony at trial concerning the extent

to which the defendant showed remorse at

the hospital and at his son's funeral.

During the days following Halloween,

O'Bryan gave conflicting stories as to

the origin of the pixy styx, but he

eventually claimed that the pixy styx

came from the Melvin home. Mr. Melvin

was at work, however, until late in the

evening on Halloween.

O'Bryan was charged

with and convicted of capital murder. At

the sentencing proceeding, the State

reintroduced the evidence that it had

presented at trial and the defendant

presented nine lay witnesses who stated

that they did not believe that O'Bryan

was likely to be a danger to society in

the future. The jury answered the two

special issues affirmatively

and O'Bryan was sentenced to die.

O'Bryan's conviction

and sentence were affirmed by the Texas

Court of Criminal Appeals on September

26, 1979. O'Bryan v. State, supra. His

application for a writ of certiorari to

the United States Supreme Court was

denied in 1980, O'Bryan v. Texas,

446 U.S. 988 , 100 S.Ct. 2975, 64

L.Ed.2d 846 (1980), as was his

first application for state habeas

corpus relief.

In July, 1980, he

filed a petition for federal habeas

corpus relief, which was dismissed

without prejudice so that he could

return to state court to present

additional unexhausted claims. His

second application for state habeas

corpus relief was denied on September 1,

1982, and his execution date set for

October 31, 1982. On September 29, 1982,

O'Bryan filed his second application for

federal habeas relief. The district

court denied his application for the

writ and stay of execution on October

20, 1982. We granted his application for

a stay and request for a certificate of

probable cause on October 27, 1982.

O'Bryan v. Estelle, 691 F.2d 706 (5th

Cir.1982).

II. THE

WITHERSPOON ISSUE.

At least seventeen

persons were excused for cause from

serving on the jury on the basis of

their opposition to the death penalty.

O'Bryan challenges the exclusion of

three of them: Jurors Wells, Pfeffer,

and Bowman.

In Witherspoon v.

Illinois, 391 U.S. 510, 88 S.Ct. 1770,

20 L.Ed.2d 776 (1968), the Supreme Court

set aside a defendant's death sentence

where members of the venire had been

excluded solely because they had

conscientious scruples against capital

punishment. The Court held that a

potential juror could not be excused for

cause on the basis of his opposition to

the death penalty unless he was "irrevocably

committed, before the trial has begun,

to vote against the penalty of death

regardless of the facts and

circumstances that might emerge in the

course of the proceedings." Id. at 522

n. 21, 88 S.Ct. at 1777 n. 21.

Such persons may be

excluded only if they make it

unmistakably clear (1) that they would

automatically vote against the

imposition of capital punishment without

regard to any evidence that might be

developed at the trial of the case

before them, or (2) that their attitude

toward the death penalty would prevent

them from making an impartial decision

as to the defendant's guilt.

Id. (emphasis in

original). The Supreme Court reasoned

that a jury from which all persons who

had reservations against imposing the

death penalty had been excluded was a

jury "uncommonly willing to condemn a

man to die." Id. at 521, 88 S.Ct. at

1776.

Both the Supreme

Court and this circuit have insisted

upon strict adherence to the mandate of

Witherspoon. The courts have required a

death sentence to be set aside even if

only one potential juror has been

excluded for opposing the death penalty

on grounds broader than those set forth

in Witherspoon, see Davis v. Georgia,

429 U.S. 122 , 97 S.Ct. 399, 50

L.Ed.2d 339 (1976); Marion v.

Beto, 434 F.2d 29, 32 (5th Cir.1970),

regardless of whether the state has any

peremptory challenges remaining at the

close of voir dire. Alderman v. Austin,

663 F.2d 558, 564 n. 7 (5th Cir.1982),

aff'd in relevant part, 695 F.2d 124

(5th Cir.1983) (en banc); Granviel v.

Estelle, 655 F.2d 673, 678 (5th

Cir.1981), cert. denied,

455 U.S. 1003 , 102 S.Ct. 1636, 71

L.Ed.2d 870 (1982); Burns v.

Estelle, 592 F.2d 1297, 1299 (5th

Cir.1979), aff'd, 626 F.2d 396 (5th

Cir.1980) (en banc); contra, Davis,

supra, 429 U.S. at 124, 97 S.Ct. at 400

(Rehnquist, J., dissenting).

A. The Standard of

Appellate Review.

As a threshold matter,

we address the question of the

appropriate standard of appellate review

in federal habeas proceedings in

assessing challenges to the exclusion of

jurors in state trials under Witherspoon.

The Supreme Court has never expressly

stated what the standard of review of a

Witherspoon challenge should be. Our

review of the Supreme Court's principal

Witherspoon cases, Adams v. Texas, 448

U.S. 38, 49-51, 100 S.Ct. 2521, 2528-29,

65 L.Ed.2d 581 (1980); Lockett v. Ohio,

438 U.S. 586, 595-97, 98 S.Ct. 2954,

2959-61, 57 L.Ed.2d 973 (1978); Maxwell

v. Bishop, 398 U.S. 262, 264-65, 90 S.Ct.

1578, 1580, 26 L.Ed.2d 221 (1970);

Boulden v. Holman, 394 U.S. 478, 482-84,

89 S.Ct. 1138, 1140-42, 22 L.Ed.2d 433

(1969); Witherspoon, supra, suggests to

us that in those cases, the Court was

engaging in an independent or de novo

review.

By de novo review, we

mean that the Court appears to decide

for itself, based upon a reading of the

transcript, whether a juror who was

allegedly improperly excluded under

Witherspoon has made it unmistakably

clear that he or she would automatically

vote against the imposition of the death

penalty, without regard to any evidence

that might be developed at trial, or

that his or her attitude toward the

death penalty would prevent him or her

from making an impartial decision as to

the defendant's guilt.

No deference appears

to be given to the trial court's ability

to observe the demeanor of the juror,

perhaps because Witherspoon's

requirement that a juror must make his

or her views "unambiguously" or "unmistakably

clear" suggests that there is no need

for such deference. Significantly,

however, the high Court's decisions have

generally been made in the context of a

direct criminal appeal.

Witherspoon

challenges in the lower federal courts

are raised in the context of federal

habeas proceedings. In the traditional

juror bias case, federal habeas review

of a state trial court's findings is

more narrowly circumscribed than is

appellate review in a direct criminal

appeal. See Smith v. Phillips, 455 U.S.

209, 102 S.Ct. 940, 71 L.Ed.2d 78

(1982). In Smith, the petitioner

maintained that a juror who had applied

for a law enforcement position during

the trial was presumptively biased

against him.

The state trial court

held a post-trial hearing and determined

that the juror had not been biased. The

Supreme Court held that in a federal

habeas action like the one before it,

the state court's findings with respect

to actual bias were "presumptively

correct under 28 U.S.C. 2254(d)," and

that "federal courts in such proceedings

must not disturb the findings of state

courts unless the federal habeas court

articulate[d] some basis for disarming

such findings of the statutory

presumption that they are correct ...."

102 S.Ct. at 946 (citing Sumner v. Mata,

449 U.S. 539, 101 S.Ct. 764, 66 L.Ed.2d

722 (1981)); see also Rogers v.

McMullen, 673 F.2d 1185, 1190 n. 10

(11th Cir.1982), cert. denied, --- U.S.

----, 103 S.Ct. 740, 74 L.Ed.2d 961

(1983); but see Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U.S.

717, 723, 81 S.Ct. 1639, 1642, 6 L.Ed.2d

751 (1961) (habeas case in which Supreme

Court held that juror bias is "mixed [question

of] law and fact" and therefore, it was

duty of court of appeals to "independently

evaluate the voir dire testimony of the

impaneled jurors") (quoting Reynolds v.

United States,

98 U.S. 145 , 156, 25 L.Ed. 244

(1878)).

Since a Witherspoon

challenge is a form of a challenge for

juror bias, Smith would seem to indicate

that a state court's factual findings

with respect to a juror's willingness to

impose the death penalty should be

entitled to a presumption of correctness

under section 2254(d). The Court's

requirement of strict adherence to

Witherspoon, however, see, e.g., Davis

v. Georgia,

429 U.S. 122 , 97 S.Ct. 399, 50

L.Ed.2d 339 (1976) (death

sentence must be set aside even if only

one prospective juror is excluded in

violation of Witherspoon), leaves us

with some doubts about whether the Court

would apply the traditional juror bias

standard of review to a Witherspoon

challenge.

Further, the Supreme

Court has not been entirely consistent

in its treatment of the juror bias

cases. Compare Smith, supra (presumption

of correctness accorded state court's

findings with respect to actual bias),

with Irvin, supra (juror bias is mixed

question of law and fact to be

independently reviewed by appellate

court).

The State maintains

that a state court's factual findings

are entitled to a presumption of

correctness under section 2254(d) in

Witherspoon challenges as well. See

Alderman v. Austin, 695 F.2d 124, 130

(5th Cir.1983) (en banc) (Fay, J.,

dissenting); Darden v. Wainwright, 699

F.2d 1031, 1037-38 (11th Cir.),

rehearing en banc granted, 699 F.2d 1043

(11th Cir.1983) (Fay, J., suggesting

that Sumner presumption applies, but

apparently engaging in independent

review of the propriety of the state

trial court's exclusion of prospective

jurors).

Like the Supreme

Court, however, the lower federal courts,

without expressly establishing a

standard of review, appear to engage in

a de novo review of Witherspoon

challenges in federal habeas proceedings.

McCorquodale v. Balkcom, 705 F.2d 1553,

1556-57 n. 9 (11th Cir.1983); Bell v.

Watkins, 692 F.2d 999, 1006-08 (5th

Cir.1982); Williams v. Maggio, 679 F.2d

381, 384-86 (5th Cir.1982) (en banc),

cert. denied, --- U.S. ----, 103 S.Ct.

3553, 77 L.Ed.2d 1399 (1983); Alderman

v. Austin, 663 F.2d 558, 562-64 (5th

Cir.1982), aff'd in relevant part, 695

F.2d 124 (5th Cir.1983) (en banc);

Granviel v. Estelle, 655 F.2d 673,

677-78 (5th Cir.1981); Burns v. Estelle,

592 F.2d 1297, 1300-01 (5th Cir.1979),

aff'd, 626 F.2d 396, 397-98 (5th

Cir.1980) (en banc); Marion v. Beto, 434

F.2d 29, 31 (5th Cir.1970).

Some judges have

suggested a third possibility: according

some deference to the trial court's

decision in light of its opportunity to

observe the juror's demeanor while he or

she is answering the questions on voir

dire. Judge Kravitch recently suggested

that where the questions asked of the

prospective jurors are precise and

closely track the language in

Witherspoon, an appellate court's

deference to the trial court's

assessment of the clarity of the juror's

answers is appropriate. McCorquodale v.

Balkcom, 705 F.2d 1553, 1561 (11th

Cir.1983) (Kravitch, J., dissenting);

see also Mason v. Balkcom, 487 F.Supp.

554, 560 (M.D.Ga.1980) (noting trial

judge's opportunity to observe and

listen to juror, but engaging in

independent analysis of Witherspoon

challenge), rev'd on other grounds, 669

F.2d 222 (5th Cir.1982), cert. denied,

--- U.S. ----, 103 S.Ct. 1260, 75 L.Ed.2d

487 (1983).

The McCorquodale

majority, however, carefully "scrutinized

the record in [its own] effort to

ascertain the correctness of the trial

court's finding with regard to a

venireman's convictions about capital

punishment," 705 F.2d at 1556-57, n. 9,

and noted that in Aiken v. Washington,

403 U.S. 946 , 91 S.Ct. 2283, 29

L.Ed.2d 856 (1971), the Supreme

Court summarily reversed a death

sentence where the state court had found

no Witherspoon violation and had

accorded some deference to the trial

court.

As discussed above,

however, our review of the case law

reveals that the courts have not

specifically established a standard for

appellate or collateral review of

Witherspoon challenges. While a state

trial court's factual findings with

respect to juror bias may normally be

entitled to a presumption of correctness

in a federal habeas proceeding, Smith,

supra, or at least to some deference in

light of the trial court's opportunity

to observe the prospective juror during

voir dire, the federal courts appear to

engage in a de novo review of the trial

court's conclusions in cases where the

defendant complains of a Witherspoon

violation. Fortunately, we do not have

to resolve the question whether and to

what extent we should defer to the state

court's findings because we have

concluded that even if we proceed under

the more exacting standard resulting

from de novo review, the trial judge's

exclusion of the three jurors in this

case was proper under Witherspoon.

B. Juror Wells.

The first prospective

juror excused for cause who has merited

the defendant's attention in these

habeas proceedings was the Reverend

Charles D. Wells. While Wells was able

to imagine a case where a juror would

vote to impose the death penalty, he was

unable to see himself doing it, and on

further questioning stated that he would

automatically vote against the death

penalty:

Q. Mr. Wells, I'm

Mike Hinton, as the Court told you

awhile ago for the State, and this is my

co-counsel, Mr. Vic Driscoll. We come

here representing the State of Texas in

this case in which we are seeking as the

punishment for this defendant the

penalty of death.

Let me begin then by

asking you whether or not you have any

conscientious, moral or religious

scruples against the imposition of the

penalty of death in the electric chair?

A. Let me say that

morally, I do, and I don't think that I

am capable of issuing a penalty of death

to any man.

Q. All right. Again,

as Judge Price told you a moment ago, no

one is here to quarrel with your

feelings and you certainly are entitled

to your opinions as all of us are in our

good country, and that includes your

feelings about the death penalty. But

under the law I must ask you this

further additional question, Reverend,

which is, I take it from your answer

that you cannot imagine a case of murder

where you could, as one of twelve jurors,

vote to send someone to the electric

chair as a punishment for their offense

even though it was authorized by statute?

A. Would you repeat

yourself now, please?

Q. Yes, sir. My

question that I must ask you then, based

upon your former answer is, I take it

that because of the feelings that you do

have that you are entitled to have,

moral feelings, religious feelings, that

you cannot imagine a case where you,

sitting on a jury, could vote to send

someone to death in the electric chair

as a punishment for their crime even

though the law authorizes such penalty?

A. I can imagine it,

but I can't see myself doing it.

Q. All right. Then, I

believe we must [be] somewhere between

our hypothetical case where you can

imagine a jury doing it?A. Yes.

Q. But you can't

imagine yourself doing it as one of

those jurors, is that correct, sir?

A. I can hardly see

myself doing it, yes.

Q. All right. Now, I

don't want you to get angry with me and

I'm not trying to argue with you, but I

have to ask you for your answer, because

this lady is taking down your testimony

at this time for the record.

I take it then from

your answer that because of your

religious and moral principles and

feelings that you are certainly entitled

to have, you cannot imagine a case where

you would vote for the imposition of

death in the electric chair. Is that

correct, sir?

A. No, I can't.

MR. HINTON: I thank

you, sir. We submit that the juror is

not qualified, Your Honor.

EXAMINATION BY THE

COURT

Q. Mr. Wells, let me

ask you a question before they have the

right to ask you questions.

Because of your moral

or religious scruples, would you, if you

were a member of the jury, would you

automatically vote against the

imposition of capital punishment no

matter what the trial revealed?

A. As far as the

electric chair is concerned?

Q. Would you

personally, if you were a member of a

jury, would you automatically vote

against the imposition of the death

penalty no matter what the trial

revealed?

A. Yes, I would.

Q. All right.

A. I would vote

against it.

2 Trial Transcript at

763-66.

In Texas, however, a

juror does not technically vote to

impose the death penalty. Instead, the

trial judge sentences the defendant to

die if, and only if, the jury answers

two, sometimes three, statutory

questions in the affirmative. Following

the examination by counsel for the State

and by the court set forth above,

counsel for the defendant directed

Wells' attention to those two questions:

Q. All right. You

understand of course, nobody would ask

you personally to put somebody to death.

You understand that. You personally do

not have to pull the switch or something?

A. I understand that.

Q. Surely. And of

course there's a lot of steps to go to

between the time you start trial and the

time you end the testimony and the

defense puts on their testimony and of

course, there's a finding of guilt. You

understand that. You do now if you

haven't before. Is that correct?

A. Yes.

Q. All right. And

then, after a finding of guilt, if there

is one, certain questions will be

submitted to you as a juror. Now, are

you saying at this time that under no

circumstances, regardless of what the

testimony would be, under no

circumstances could you vote for the

death penalty?

A. I don't think

there are any that I possibly could vote

for the death penalty.

Q. All right. Let me

ask you this, sir, if you were selected

as a juror, even though the State has

asked for the death penalty, could you

consider these two issues--and I'll ask

you the issues that you would perhaps be

asked to consider. All right?

A. All right.

Q. All right. The

first issue would be whether the conduct

of the defendant that caused the death

of the deceased was committed

deliberately and with the reasonable

expectation that the death of the

deceased or another would result. Could

you answer that question, sir, after you

had gotten all the facts?

A. Yes, Yes.

Q. You could answer

that all right?

A. Yes.

Q. And that wouldn't

have any trouble with your conscience,

would it?

A. No.

Q. Then of course

there would be another question, and

that would be whether there is [a]

probability that the defendant would

commit criminal acts of violence that

would constitute a continuing threat to

society. Now, could you possibly answer

that question?

A. Yes, I possibly

could answer that question.

Q. And would you have

any quarrel or any problem with those

questions?

A. I don't think so.

Q. All right. And if

you answered those questions, of course,

it wouldn't be up to you to do anything

to this defendant. Those are merely

questions that you answer to the Court.

Isn't that correct?

A. I would say yes.

Q. Could you do that,

sir?

A. I could be as

liberal in answering the questions as I

could.

Q. And you would

answer those questions truthfully, would

you not?

A. Yes, as far as my

opinions are concerned.

Q. I know you're a

minister, are you not?

A. Yes, sir. That's

correct.

Q. And you could

answer those questions to the best of

your ability and truthfully, could you

not?

A. Yes.

2 Trial Transcript at

768-70. In spite of Wells' assurance

that he could and would answer the

statutory questions, the trial court

granted the State's request that Wells

be excused for cause. Significantly, at

no time did defense counsel explain to

Wells that if he and the other jurors

answered the statutory questions in the

affirmative, the trial judge would be

required to sentence the defendant to

death, and our review of the record

indicates that at no point in the

proceedings before the voir dire of

Wells did the court or counsel render

any such explanation. We thus do not

know whether, in saying that he could

and would answer the two statutory

questions truthfully, Wells understood

what the effect of those answers could

be.

The Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals was recently presented

with a Witherspoon challenge involving a

prospective juror whose views were in

some respects strikingly similar to

those of Wells. In Cuevas v. State, 641

S.W.2d 558 (Tex.Crim.App.1982) (en banc),

venireman Ward initially stated, in the

words of the court of criminal appeals,

"that under no circumstances could he

participate as a juror in returning a

verdict that would require the court to

assess the death penalty." Id. at 560.

After the "bifurcated

system in Texas for assessing guilt and

punishment in capital murder cases" had

been "carefully" explained to him,

however, and after he had been informed

that the court, not the jury, would

impose the penalty, Ward told the trial

court that he could set aside his

objections to capital punishment and

answer the statutory questions on the

basis of the evidence presented. Id.

While the court of

criminal appeals relied on Adams, rather

than Witherspoon, in setting aside

Cuevas' death sentence,

the court was convinced that Ward could

not have been excluded consistently with

Witherspoon either, because "[h]e

repeatedly stated that he could follow

the law and convict upon proper evidence

of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt,

despite his opposition to the death

penalty." 641 S.W.2d at 563.

Cuevas sharpens the

ultimate question presented by Wells'

exclusion. Just as a juror may be able

to put aside his or her opposition to

the death penalty and obey the law, so

may he or she decide that he or she can

determine the facts, i.e., answer the

questions, as long as he or she is not

the one who must actually pronounce the

fatal words.

If this is the juror's conclusion, then

he or she cannot be excluded under

Witherspoon. Ward in Cuevas was just

such a juror, and the Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals held that his exclusion

was error.

The threshold

question presented by Wells' voir dire

is whether Wells had the same views as

had Ward. The record indicates that he

may have held those views. He stated

that he could and would answer the

statutory questions truthfully. But in

view of the fact that the record does

not contain an explanation to Wells of

the effect of "yes" answers to those

questions by the jury, we do not know

from the record whether Wells, like

Ward, could put aside his opposition to

the death penalty and obey the law, i.e.,

answer the statutory questions

truthfully, knowing the possible effect

of his answers to those questions.

We can only speculate.

If the requirement of Witherspoon and

its progeny--that a venireman must make

"unmistakably clear" his or her

inability to follow the law and abide by

his or her oath, Adams, supra, 448 U.S.

at 48, 100 S.Ct. at 2528; accord Boulden,

supra, 394 U.S. at 483-84, 89 S.Ct. at

1141-42--means that an appellate or

federal habeas court that cannot be

certain from the face of the record

about a venireman's inability to follow

the law must, without any further

consideration, grant the writ, then we

would be compelled to do so here.

The State argues that

we should not apply such a rule in the

circumstances of this case. It maintains

that it clearly established Wells'

automatic opposition to the death

penalty during its initial examination

of him. Having done so, the State argues

that if the petitioner wished to

rehabilitate Wells as a juror

successfully, it was incumbent upon

defense counsel to take his inquiry into

Wells' ability to answer the statutory

questions one step further by clarifying,

on the record, whether Wells understood

the possible effect of his answers to

those questions. The State argues that,

since the defense failed to take that

step, the exclusion of Wells on the

basis of his initial unequivocal

statements of automatic opposition to

the death penalty was proper. We agree

with the State.

A fair reading of

Wells' testimony in response to the

initial questioning by the State and by

the trial court indicates that Wells

stated clearly, forcefully and without

any equivocation that he would

automatically vote against the

imposition of the death penalty no

matter what the trial revealed. Had the

voir dire ended with the court's

questioning, the State would clearly

have properly obtained the exclusion of

Wells under Witherspoon.

If the defense wished

to rehabilitate Wells by demonstrating

that he could obey the law regardless of

his opposition to the death penalty,

perhaps because of the distinction

between the jury as the fact-finder and

the judge as the sentencer that Ward

found persuasive in Cuevas, then it was

incumbent upon the defense to establish,

on the record, Wells' ability to engage

in that fact-finding function with

knowledge of the possible effect of

those findings on the defendant's fate.

This the defense failed to do.

Accordingly, we hold that the exclusion

of Wells on the basis of his initial

clear and unequivocal statements that he

would automatically vote against the

death penalty no matter what the trial

revealed was proper under Witherspoon

and its progeny.

This holding is not

inconsistent with Burns, supra, in which

we held that the exclusion of juror Doss

was improper because we were forced to

speculate about whether she could put

aside her disbelief in the death penalty

and follow the law. 592 F.2d at 1301. In

Burns, Doss affirmed that she "did not

believe in" the death penalty three

times and stated "that the mandatory

penalty of death or life imprisonment

would 'affect' her 'deliberations on any

issue of fact in the case.' " Id. The

trial court excluded Doss solely on the

basis of those statements, and it

rejected defense counsel's suggestion

that Doss be asked further questions

because it could not imagine what else

could have been asked. Unfortunately, we

could:

She could have been

asked whether, despite her expressed

convictions, she could put her disbelief

aside and do her duty as a citizen. Her

answer might have been that she could.

Or she could have been asked what effect

the presence of a possible death

sentence would have on her deliberations.

Her answer might have been that she

would wish to be very sure of guilt, to

be thoroughly convinced, before she

could find facts in such a way that the

death penalty might result. Either

answer would doubtless have

rehabilitated her for jury service. An

answer that she would not take or could

not comply with the required oath not to

be "affected" in her deliberations would

doubtless, upon a proper definition of "affected"

as meaning "disablingly" or "insurmountably"

affected, have clearly disqualified her.

Id. (emphasis in

original). We went on to explain that

the speculations caused by the

inadequacy of Doss' responses to the

questions initially posed to her, in

combination with the trial court's

failure to permit additional questioning

by the defense, required us to hold that

her exclusion was improper under

Witherspoon:

To be sure, these are

mere speculations about what her answers

to such [additional] questions might

have been. The point is that nothing in

her actual answers forecloses them. Her

mere acknowledgment that the penalty

would "affect" her deliberations does

not do so: what candid and responsible

citizen would not admit as much, could

truthfully swear the proposition to be

one of no concern whatever?

Id.

In contrast to the

voir dire in Burns, neither the State

nor the trial court has left us to

speculate about the nature of Wells'

opposition to the death penalty. The

prosecutor did not settle for Wells'

statement that he did not think that he

was "capable of issuing the penalty of

death to any man," or that he could

"imagine" but could not "see" himself

voting to send someone to death. 2 Trial

Transcript at 764-65. The prosecutor did

not sit down until Wells had stated

unequivocally that he could not imagine

a case where he would "vote for the

imposition of death." Id. at 765.

After the prosecutor

had finished his questioning, the court

took up the task and asked whether Wells

would "automatically vote against the

death penalty no matter what the trial

revealed," to which Wells replied that

he would. Id. at 766. If we are forced

to speculate in this case, it is defense

counsel, not the State or the trial

judge, who failed to ask the necessary

question.

We have here the

converse of the situation in Burns.

Nothing in Wells' answers to defense

counsel's questions forecloses the

possibility that he would not have

answered the statutory questions on the

basis of the evidence if he knew that an

affirmative answer to both questions

would mandate the defendant's execution.

The State established Wells' unequivocal

opposition to the death penalty beyond

speculation; it was then incumbent upon

the defendant, if he wished to

rehabilitate the juror, to ask enough

questions to demonstrate that Wells

could perform his fact-finding function

in spite of his opposition to the death

penalty.

We were recently

confronted with a similar failure by

defense counsel to rehabilitate a juror

who had expressed her opposition to the

death penalty in Porter v. Estelle, 709

F.2d 944 (5th Cir.1983). In Porter, in

response to the State's questions,

prospective juror Herndon had repeatedly

expressed "longstanding convictions

against the death penalty that would [have]

require[d] her to vote against [it] no

matter what the trial revealed." 709

F.2d at 948.

She maintained her

opposition in response to two questions

from defense counsel but when asked

whether she could "put her convictions

aside and do her duty 'as a Juror in a

Capital Murder case,' " she replied that

she could. Id. (emphasis in original).

When defense counsel objected to the

State's challenge for cause, the State

pointed out that the general question

asked about Herndon's ability to do her

"duty as a juror" had not included "the

second predicate question in Burns ....

[that] if it meant sentencing a man to

death, could you follow that duty?' " Id.

Defense counsel did not ask any more

questions and the juror was excused for

cause. We held in Porter that

[i]n view of

Herndon's repeated, firm, and

unequivocal statements of irrevocable [opposition

to the] imposition of the death penalty

under any circumstances, we are unable

to say her limited reply that "she could

do her duty as a juror " indicated any

vacillation or equivocation in her

previous statement of unalterable

opposition to imposition of the death

penalty.

709 F.2d at 948-49 (emphasis

in original). Like the defense counsel

in Porter, defense counsel here did not

ask enough questions to demonstrate that

Wells' previously expressed unequivocal

opposition to the death penalty would

not prevent him from performing his

function as a juror in a capital case.

C. Juror Pfeffer.

Juror Pfeffer

presents the opposite problem from

Wells. Indeed, the voir dire of Pfeffer

may be the quintessential example of a

situation in which it would be

appropriate for an appellate court to

give at least some deference to the

trial judge, who has had the opportunity

to observe the juror as he or she

struggles to give an honest answer to

difficult questions. Regardless of

whether such deference is advisable, our

own independent review of the record

indicates that Pfeffer's exclusion was

not in violation of Witherspoon.

As we observed in our

decision to grant O'Bryan a stay of

execution, and as the court of criminal

appeals recognized, during the initial

two-thirds of Pfeffer's lengthy voir

dire examination (covering twenty-four

pages in the transcript), he was

equivocal in stating

his position on capital punishment. He

described himself as a "borderline

thinker" on the issue of capital

punishment, and expressed doubt that he

could make the proper judgment because

of his "mixed feelings" concerning the

infliction of the death penalty.

O'Bryan v. Estelle,

691 F.2d 706, 709 (5th Cir.1982). When

informed by the trial court that he must

give a definitive answer, Pfeffer stated

that he "would have to say" that he

could not vote to impose the death

penalty, although he continued to add

caveats from time to time, referring to

the necessity for giving the judge a "yes

or no answer," "to give a correct answer,"

or "for the good of everyone concerned:"

THE COURT: Well, the

law requires that we have to have a

definite answer.

JUROR PFEFFER: I

understand, right.

THE COURT: Because

the law does allow people to be excused

because of certain beliefs that could be

prejudicial or biased for one side or

the other, and both sides just want to

know if you can keep an open mind,

consider the entire full range of

punishment, whatever that may be, and

under the proper set of circumstances,

if they do exist and you feel they exist,

that you could return that verdict. And

that's in essence what they're asking.

JUROR PFEFFER:

Indirectly, I guess I would have to say

no.

THE COURT: You could

not?

JUROR PFEFFER: I

would have to say no then, to give you a

yes or no answer.

THE COURT: Then, am I

to believe by virtue of that answer that

regardless of what the facts would

reveal, regardless of how horrible the

circumstances may be, that you would

automatically vote against the

imposition of the death penalty?

JUROR PFEFFER: As I

say, I don't know.

THE COURT: Well,

that's the question I have to have a yes

or no to.

JUROR PFEFFER: Right.

THE COURT: And you're

the only human being alive who knows,

Mr. Pfeffer.

JUROR PFEFFER: Right,

I understand. If I have to make a choice

between yes and no, I would say that I

couldn't make the judgment.

3 Trial Transcript at

882-84. Although Pfeffer interspersed

his answers from this point on in his

voir dire with caveats or qualifications

such as those referred to above, there

are at least two instances in which, if

we focus on a specific question and

answer, he gave unqualified answers:

THE COURT: You

yourself are in such a frame of mind

that regardless of how horrible the

facts and circumstances are, that you

would automatically vote against the

imposition of the death penalty? Is that

correct?

JUROR PFEFFER: Well,

if it says a yes or no, I would have to

say yes, I would automatically vote

against, to give a correct answer.

THE COURT: You would

vote against?

JUROR PFEFFER: Yes.

3 Trial Transcript at

884-85 (emphasis added).

Q. (By Mr. Harrison)

Then, under no circumstances, Mr.

Pfeffer, could you even think of voting

or answering those questions if the

result of those questions were to be to,

in effect, give somebody the death

penalty. Is that correct?

A. I think at the

present time that's correct, yes.

Id. at 892.

In O'Bryan's view,

while Pfeffer had "reservations" or "mixed

emotions" about the death penalty, and

while he was seriously concerned about

his own ability to assess the death

penalty, he was willing to do so in a "very,

very extreme set of circumstances."

If this were an accurate view, then

Pfeffer's exclusion would have been

improper. In Witherspoon, one of the

venirewomen excluded stated that "she

would not 'like to be responsible for

... deciding somebody should be put to

death.' " 391 U.S. at 515, 88 S.Ct. at

1773. In the footnote accompanying this

description of the juror's feelings, the

Supreme Court cited, apparently with

approval, a Mississippi case that

reversed a trial court's exclusion of

jurors who did not wish to decide

whether a person should die:

The declaration of

the rejected jurors, in this case,

amounted only to a statement that they

would not like ... a man to be hung. Few

men would. Every right-thinking man

would regard it as a painful duty to

pronounce a verdict of death upon his

fellow-man.

Id. at 515 n. 8, 88

S.Ct. at 1773 n. 8 (quoting Smith v.

State, 55 Miss. 410, 413-14 (1887));

accord Burns, supra, 592 F.2d at 1299 n.

2. Witherspoon makes it clear that

neither a deep reluctance to pronounce

the death penalty, short of absolute

refusal to do so, nor the reservation of

the death penalty for only an extreme

set of circumstances, is a ground for

exclusion.

391 U.S. at 522 n. 21, 88 S.Ct. at 1777

n. 21.

A careful review of

the transcript indicates that during the

initial two-thirds of Pfeffer's voir

dire, he did indeed suggest that he

would be able, in an extreme set of

circumstances, to assess the death

penalty. At that point, however,

Pfeffer's attitude, or at the very least,

his answers, changed when he stated that

"if [he had] to make a choice between

yes and no," 3 Trial Transcript at 884,

he would have to say that he would

automatically vote against imposition of

the death penalty. We conclude that this

case is controlled by our en banc

decision in Williams v. Maggio, 679 F.2d

381 (5th Cir.1982) (en banc), cert.

denied, --- U.S. ----, 103 S.Ct. 3553,

77 L.Ed.2d 1399 (1983).

Juror Brou in

Williams stated that there were "certain

cases where you read about them and they

are so hideous that you just think, oh,

the death penalty would be the only good

outcome," 679 F.2d at 305, a statement

similar to Pfeffer's statement that he

could assess the death penalty in a "very,

very extreme set of circumstances." The

prosecutor continued his probing,

however, and in response to a leading

question about Williams' particular

case, Brou stated that she felt that she

could not impose the death penalty:

Q. So you feel that

you could not return the death penalty?

A. (Ms. Brou) No.

Id. (emphasis in

majority opinion).

Viewing Brou's

initial uncertainty in conjunction with

her ultimate response to the

prosecutor's question about her ability

to return the death penalty, the

majority of this court concluded in

Williams that "the record of [Brou's]

automatic opposition to the death

penalty [was] established." Id. The en

banc majority specifically rejected the

contention that under Witherspoon "exclusion

of a venireman is impermissible unless

he states in response to all questions

that he absolutely refuses to consider

the death penalty." 679 F.2d at 386 (emphasis

added).

It would seem that

under Williams, it is the juror's

ultimate conclusion about whether he or

she is irrevocably opposed to the death

penalty that is critical. Absent

effective rehabilitation of the sort

that we found lacking in defense

counsel's questioning of Wells and the

Texas Court of Criminal Appeals found

present in Cuevas, a juror's ultimate

statement of unequivocal opposition to

the death penalty will justify his or

her exclusion under the Williams court's

interpretation of Witherspoon.

Pfeffer's unequivocal

statement that he would automatically

vote against the death penalty, 3 Trial

Transcript at 885, was sufficient to

justify his exclusion under Williams;

his earlier statement that he could

assess the death penalty in an extreme

set of circumstances, his prolonged

uncertainty and his caveats and

qualifications preceding that

unequivocal statement do not undercut

the validity of that exclusion. The

caveats and qualifications following

that unequivocal statement do not amount

to the kind of effective rehabilitation

of Pfeffer that would be necessary for

us to hold that his exclusion was error.

O'Bryan suggests that

Pfeffer's ultimate statements do not

accurately reflect Pfeffer's position.

O'Bryan contends that the trial judge

mistakenly viewed Witherspoon as an "exclusionary

rule,"

and that the judge was unwilling to

accept Pfeffer's deep, agonized

reluctance to pronounce the death

penalty. The defendant maintains that

the trial court, in effect, coerced

Pfeffer into taking a position that he

would automatically vote against the

imposition of the death penalty

regardless of the facts established at

trial.

Our review of the

entire voir dire, encompassing seven

volumes of the trial record, indicates

that the trial judge did not generally

view Witherspoon as an exclusionary rule.

Instead, he painstakingly questioned,

and permitted counsel to question, each

and every juror who expressed discomfort

about imposing the death penalty,

excluding some for cause but refusing to

exclude others, thereby forcing the

State to exercise its peremptory

challenges.

We cannot say that

the court's probing of Pfeffer's answers

in an attempt to find some basis on

which to evaluate his true feelings was

improper. Throughout the voir dire,

Pfeffer continued to express concern

about his ability to pronounce the death

penalty. The trial judge may have

thought that Pfeffer's professed

willingness to assess the death penalty

in a "very, very extreme set of

circumstances" was a smoke screen for

what was really an inability to assess

the death penalty under any circumstance.

Under this view, we

would have to say that a trial judge,

harboring those suspicions about the

person in front of him or her, has the

right, within certain limitations, to

pursue a line of questioning designed to

flush out the venireman's true views.

Indeed, an appellate court confronted

with the question whether such an

exclusion was proper, and with the

apparent necessity of making an

independent review based on the cold

record, will expect no less. The trial

court in this case succeeded in

obtaining an answer from Pfeffer that he

could not impose the death penalty.

Under these circumstances, we cannot say

that Pfeffer's exclusion was improper.

Williams, supra.

D. Juror Bowman.

O'Bryan's final

complaint about the voir dire involves

the exclusion of juror Bowman. Like

Pfeffer, Bowman was originally unsure of

his feelings about the death penalty,

but on further questioning he stated

that he could not vote for it. When

asked about a crime "closer to home,"

however, he said that he could consider

the death penalty if the victim "was one

of [his] family." 3 Trial Transcript at

918.

We agree with the

Texas Court of Criminal Appeals that

Bowman's response that he could impose

the death penalty if a member of his

family had been killed does not

invalidate the trial court's excusal of

him for cause. If the victim had been a

member of Bowman's family, he would have

been "unable to serve as a juror because

of his interest and prejudice in the

case." O'Bryan, supra, 591 S.W.2d at 473

(citing Tex.Code Crim.Pro.Ann. art.

35.16 (Vernon 1966 & Supp.1983)). The

statement that a person could impose the

death penalty only in a case in which he

or she would not be permitted to serve

is virtually the equivalent of a

statement that the juror would never

vote in favor of capital punishment.

III. THE

CONSTITUTIONALITY OF THE CAPITAL

SENTENCING PROCEDURE.

O'Bryan contends that

the Texas capital sentencing procedure,

Tex.Code Crim.Pro.Ann. art. 37.071

(Vernon 1981), is unconstitutional

because it does not provide for

instructions to the jury concerning

mitigating circumstances.

He argues that in the absence of such

instructions, the determination of

punishment is left to the unbridled

discretion of the jury, resulting in the

imposition of the death penalty in an

arbitrary and capricious manner, in

violation of the eighth and fourteenth

amendments. See Furman v. Georgia, 408

U.S. 238, 92 S.Ct. 2726, 33 L.Ed.2d 346

(1972).

Relying on the

Supreme Court's holdings in Eddings v.

Oklahoma, 455 U.S. 104, 102 S.Ct. 869,

71 L.Ed.2d 1 (1982), that a sentencer

must consider all of the mitigating

evidence before sentencing someone to

die, and in Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S.

586, 98 S.Ct. 2954, 57 L.Ed.2d 973

(1978), that the sentencer cannot be

precluded from considering any

mitigating factors, O'Bryan maintains

that an instruction concerning

mitigating evidence is constitutionally

mandated.

The State claims that

O'Bryan cannot be heard to complain

about the trial court's failure to give

a jury instruction on mitigating

circumstances because he did not make a

contemporaneous objection to the court's

charge on this ground or request such an

instruction at trial, as required by

state law. Tex.Code Crim.Pro.Ann. arts.

36.14, .15 (Vernon 1981, superseded). It

is, of course, settled law that "when a

procedural default bars state litigation

of a constitutional claim, a state

prisoner may not obtain federal habeas

relief absent a showing of cause and

actual prejudice." Engle v. Isaac, 456

U.S. 107, 129, 102 S.Ct. 1558, 1572, 71

L.Ed.2d 783 (1982); accord, Wainwright

v. Sykes, 433 U.S. 72, 97 S.Ct. 2497, 53

L.Ed.2d 594 (1977).

On the other hand, we

are not "barred from reviewing a claim

by a state procedural rule when the

state courts themselves have not

followed the rule." Bell v. Watkins, 692

F.2d 999, 1004 (5th Cir.1982); accord,

Ulster County Court v. Allen, 442 U.S.

140, 154, 99 S.Ct. 2213, 2223, 60 L.Ed.2d

777 (1979); Henry v. Wainwright, 686

F.2d 311, 313 (5th Cir.1982). The

problem here is that the state court did

not say whether it was denying the

petitioner habeas corpus relief on the

basis of his procedural default or on

the merits of his claim; it simply

denied his petition without comment.

We were recently

confronted with the problem of

interpreting a state court's silence

with respect to the grounds for its

denial of a state habeas petitioner's

claim in Preston v. Maggio, 705 F.2d 113

(5th Cir.1983). We determined that the

same considerations should be applied to

cases in which the state court has

denied relief without offering any

reasons for its denial as are applied to

cases where a state court has been "less

than explicit." Id. at 116. We included

among those considerations:

Whether the court has

used procedural default in similar cases

to preclude review of the claim's merits,

whether the history of the case would

suggest that the state court was aware

of the procedural default, and whether

the state court's opinions suggest

reliance upon procedural grounds or a

determination of the merits.

Id. (citing Ulster

County Court, supra, 442 U.S. at 147-54,

99 S.Ct. at 2219-23). Applying the

Preston criteria to O'Bryan's case, we

conclude that the state court presumably

denied his claim on the basis of his

procedural default.

The Texas courts have

held that in the absence of objections

to the charge or a specially requested

charge, no errors therein can be

considered on appeal "unless it appears

that the defendant has not had a fair

and impartial trial." Boles v. State,

598 S.W.2d 274, 278 (Tex.Cr.App.1980).

And, in determining whether fundamental

error is present, it is proper to view

the charge as a whole.

White v. State, 610

S.W.2d 504, 506 (Tex.Cr.App.1981) (en

banc). In Williams v. State, 622 S.W.2d

116 (Tex.Cr.App.1981) (en banc), cert.

denied,

455 U.S. 1008 , 102 S.Ct. 1646, 71

L.Ed.2d 876 (1982), the Texas

Court of Criminal Appeals refused to

hear a capital murder defendant's

contention that he was entitled to a

mitigating circumstances instruction

during the sentencing phase of his trial

where he had failed to object or request

such an instruction at trial. The court

held: "Absent such an objection or

requested instruction, the trial court's

failure to charge the jury as to the

consideration of mitigating

circumstances was not reversible error."

Id. at 120.

Williams' position

was the same as O'Bryan's: Williams

contended that his death sentence had

been imposed unconstitutionally because

the jury had not been given a mitigating

circumstances instruction, but he had

never requested such an instruction at

trial. Under these circumstances, the

Texas court concluded that Williams'

procedural default precluded review of

his constitutional claim. O'Bryan has

not offered us any indication that the

court would not have made the same

decision here.

Further, we know that the Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals had been made aware of

O'Bryan's procedural default, since the

State raised the matter in its answer

opposing the petitioner's second

application for habeas relief.

O'Bryan argues that

his failure to object to the trial

court's charge should not bar his claim

because the Texas court's decisions in

Williams, supra, and Quinones v. State,

592 S.W.2d 933 (Tex.Cr.App.) (en banc),

cert. denied,

449 U.S. 893 , 101 S.Ct. 256, 66

L.Ed.2d 121 (1980), placed him in

a "Catch-22" situation. As discussed

above, the court of criminal appeals

held in Williams that it would not

review a challenge to the sentencing

instructions where the defendant had

made no objection to those instructions

at trial. In Quinones, the defendant had

requested and been denied a charge on

mitigating circumstances. The court of

criminal appeals held that no such

charge was necessary and overruled his

exception:

Appellant was

entitled to present evidence of any

mitigating circumstances and did present

such evidence, including a broad

discussion of his personal and family

background. The question then is whether

the language of the special issue is so

complex that an explanatory charge is

necessary to keep the jury from

disregarding the evidence properly

before it. In King v. State, 553 S.W.2d

105 (Tex.Cr.App.1977), cert. denied,

434 U.S. 1088 , 98 S.Ct. 1284, 55

L.Ed.2d 793 (1978), this Court

held that the questions in Art. 37.071

used terms of common understanding which

required no special definition. The jury

can readily grasp the logical relevance

of mitigating evidence to the issue of

whether there is a probability of future

criminal acts of violence. No additional

charge is required.

Id. at 947. Contrary

to O'Bryan's assertion, these two

decisions do not present him with a

Catch-22 situation, since they do not

hold that a trial judge may not give a

mitigating circumstances instruction if

he or she is disposed to grant the

defendant's request. The purpose of a

contemporaneous objection requirement is

to give the trial judge the opportunity

to rule on the defendant's

constitutional claim, see Engle v.

Isaac, 456 U.S. 107, 128-29, 102 S.Ct.

1558, 1572, 71 L.Ed.2d 783 (1982); this

is what O'Bryan failed to do.

Accordingly, we hold

that the defendant is barred from

raising his claim about the absence of a

mitigating circumstances instruction in

these federal habeas proceedings. See

also O'Bryan v. Estelle, 691 F.2d 706,

710 (5th Cir.1982) (Gee, J., dissenting).

We note further that the Supreme Court's

recent decision in Zant v. Stephens, ---

U.S. ----, 103 S.Ct. 2733, 2744, 77 L.Ed.2d

235 (1983) (holding that death sentence

need not be set aside where one of three

statutory aggravating circumstances

found by juror was subsequently held to

be invalid by state supreme court but

other two were specifically upheld, and

stating that "the absence of legislature

or court-imposed standards to govern the

jury in weighing the significance of

either or both of those aggravating

circumstances does not render [capital

sentencing statute] invalid" as applied)

makes the defendant's argument on the

merits far more difficult.

O'Bryan also contends

that his punishment of death, based

solely upon the evidence introduced at

the guilt stage of trial, the state

having elected to present no evidence

bearing upon the special issue required

by article 37.071(b)(2), V.A.C.C.P.,

violated the plurality conclusion in

Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 [92 S.Ct.

2726, 33 L.Ed.2d 346] (1972); Woodson v.

North Carolina,

428 U.S. 280 [96 S.Ct. 2978, 49

L.Ed.2d 944] (1976); Roberts v.

Louisiana,

428 U.S. 325 [96 S.Ct. 3001, 49

L.Ed.2d 974] (1976).

The defendant never

explains precisely what he means by this

statement, but it seems to refer to the

contention that he made in his direct

criminal appeal that the evidence was

insufficient to support the jury's

finding that there was a probability

that he would commit criminal acts of

violence that would constitute a

continuing threat to society. O'Bryan v.

State, supra, 591 S.W.2d at 480.

We agree with the

Texas Court of Criminal Appeals that the

State's reintroduction of the evidence

presented during the guilt phase of the

trial provided sufficient evidence of

O'Bryan's future dangerousness to

support the jury's findings.

In particular, we

note that O'Bryan carefully planned the

poisoning of his own son so that he

could collect life insurance proceeds,

and that he gave the poisoned pixy styx

to four other children, including his

own daughter, in an attempt to cover up

his crime. We cannot say that no

rational trier of fact could have found

beyond a reasonable doubt that such a

man posed a continuing threat to society.

See note 18.

IV. PROSECUTORIAL

ARGUMENT.

O'Bryan complains

that his constitutional rights were

violated when the prosecutor was

permitted to comment, during closing

argument at the sentencing phase of the

trial, on defense counsel's failure to

question defense witnesses concerning

O'Bryan's reputation for being a

peaceful and law-abiding citizen, and to

suggest that counsel had a "moral

obligation" to ask this question of the

witnesses. O'Bryan contends that these

comments impermissibly shifted the

burden of disproving future

dangerousness onto the defendant, and

that the prosecutor's comments deprived

him of a fundamentally fair trial.

The trial court

overruled O'Bryan's objection to the

prosecutor's argument. The court stated

that a party is permitted, in Texas, to

comment on the failure to call certain

witnesses. The Texas Court of Criminal

Appeals agreed, noting that it "is well

settled that the prosecutor, in argument,

may comment upon the defendant's failure

to call certain witnesses." O'Bryan v.

State, 591 S.W.2d 464, 479 (Tex.Cr.App.1979)

(en banc), cert. denied,

446 U.S. 988 , 100 S.Ct. 2975, 64

L.Ed.2d 846 (1980) (citing, e.g.,

Carrillo v. State, 566 S.W.2d 902, 912 (Tex.Cr.App.1978)).

The court added that

while the burden of proving the special

issues is on the State, "the option of

coming forward with mitigating

circumstances is upon the capital

defendant." 591 S.W.2d at 479. Noting

that counsel for both the defense and

the prosecution had commented on the

failure to call witnesses,

and that the trial court had properly

charged the jury with regard to the

State's burden of proof during the

punishment phase of the trial, the Texas

Court of Criminal Appeals held that the

prosecutor's remarks had not shifted the

burden of proof to the defendant, and

that the trial court's ruling was not in

error. Id.

Our review of the

propriety of prosecutorial comments made

during a state trial is "the narrow one

of due process, and not the broad

exercise of supervisory power that [we]

would possess in regard to [our] own

trial court." Donnelly v. DeChristoforo,

416 U.S. 637, 642, 94 S.Ct. 1868, 1871,

40 L.Ed.2d 431 (1974). In the absence of

a violation of a specific guarantee of

the Bill of Rights,

we may overturn a state court conviction

only if the complained-of conduct has

made the trial fundamentally unfair. Id.

at 645, 94 S.Ct. at 1872; see also

Passman v. Blackburn, 652 F.2d 559, 567

(5th Cir.1981), cert. denied,

455 U.S. 1022 , 102 S.Ct. 1722, 72

L.Ed.2d 141 (1982); Cobb v.

Wainwright, 609 F.2d 754, 756 (5th

Cir.), cert. denied,

447 U.S. 907 , 100 S.Ct. 2991, 64

L.Ed.2d 857 (1980). Such is not

the case here.

The prosecutor's

remarks did not impermissibly shift the

burden of proving the special issues

under Tex.Code Crim.Pro.Ann. art. 37.071

(Vernon 1981). The prosecutor's comments

were at most tangentially related to the

burden of proof. The cases cited by the

defendant as examples of impermissible

burden-shifting involved specific

instructions by the trial court about

who bore the burden of proving certain

issues, see, e.g., Sandstrom v. Montana,

442 U.S. 510, 99 S.Ct. 2450, 61 L.Ed.2d

39 (1979), or a state statute

establishing the same. In re Winship,

397 U.S. 358, 90 S.Ct. 1068, 25 L.Ed.2d

368 (1970). Here the complaint is about

a prosecutor's off-the-cuff comments,

not judicial instructions.

In Cupp v. Naughten,

414 U.S. 141, 94 S.Ct. 396, 38 L.Ed.2d

368 (1973), the habeas petitioner

claimed that a state trial judge's

instruction that "[e]very witness is

presumed to speak the truth," id. at

142, 94 S.Ct. at 398, impermissibly

shifted the burden of proof. The Supreme

Court held that "[w]hatever tangential

undercutting of [the presumption of

innocence and the state's duty to prove

guilt beyond a reasonable doubt] may, as

a theoretical matter, have resulted from

the giving of the instruction on the

presumption of truthfulness is not of

constitutional dimension." Id. at 149,

94 S.Ct. at 401. The connection between

the prosecutor's comments about the

failure to question defense witnesses in

this case and the burden of proof is

even more attenuated than was the

connection in Naughten, supra.

Further, we have held

that the requirements of the federal

Constitution are satisfied as long as

the State bears the burden of proving

the aggravating circumstances. Gray v.

Lucas, 677 F.2d 1086, 1107 (5th

Cir.1982), cert. denied, --- U.S. ----,

103 S.Ct. 1886, 76 L.Ed.2d 815 (1983).

The trial court instructed the jury that

the prosecution bore the burden of

proving the defendant's future

dangerousness beyond a reasonable doubt.

The Constitution requires no more. The

question of who should produce evidence

of mitigating circumstances was a matter

of state law; the state court's decision

that the defendant bore that burden

entailed no constitutional violation.

See Gray, supra.

We find no error of

constitutional magnitude, if there be

any error at all, in the trial court's

permitting the prosecution to comment on

the defendant's failure to ask his

witnesses certain questions. As the

Texas Court of Criminal Appeals noted,

the prosecutor may comment, as a matter

of state law, on the defendant's failure

to call a material witness, and he may

draw an inference from that failure that

the testimony would have been

unfavorable. See, e.g., Carrillo, supra.

Similarly, we have

held that in federal court, "the failure

of a party to produce as a witness one

peculiarly within the power of such

party creates an inference that such

testimony would be unfavorable, and may

be the subject of comment to the jury by

the other party." United States v.

Lehmann, 613 F.2d 130, 136 (5th

Cir.1980) (quoting McClanahan v. United

States, 230 F.2d 919 (5th Cir.), cert.

denied,

352 U.S. 824 , 77 S.Ct. 33, 1 L.Ed.2d

47 (1956)).

Comment is not

permissible, however, if the "person in

question is equally available to both

parties; particularly where he is

actually in court." Id. O'Bryan did call

these witnesses, and he points out that

the prosecutor could have asked them

about the defendant's reputation for

peacefulness as easily as the defendant

could have. The prosecutor's statement

that defense counsel had a "moral

obligation" to ask certain questions of

the witnesses probably bordered on the

improper. Viewing these two comments in

the context of the trial as a whole,

however, see Houston v. Estelle, 569

F.2d 372, 377 (5th Cir.1978), we cannot

say that they deprived the defendant of

a fundamentally fair trial.

In Houston, supra,

where we set aside a state court

conviction on the basis of improper

prosecutorial comments, the prosecutor

had repeatedly made the remarks even

after he was reprimanded by the trial

judge. Further, the comments themselves

were far more egregious than those made

during O'Bryan's trial. The prosecutor

began his argument with a personal

attack on the integrity of defense

counsel, continued with a personal

opinion about the defendant's

credibility on the witness stand, and

suggested that the jury give the

defendant a long sentence so that the

defendant would have an opportunity to

rehabilitate himself, a suggestion that

was improper under state law. 569 F.2d

at 378, 380, 381 n. 12.

In contrast, the

Supreme Court refused to set aside a

defendant's conviction where the

prosecutor had expressed his personal

opinion about the defendant's guilt and

had made an improper suggestion about

the defendant's motives for standing

trial. Donnelly v. DeChristoforo, 416

U.S. 637, 642, 94 S.Ct. 1868, 1871, 40

L.Ed.2d 431 (1974). In O'Bryan's case,

the State's evidence, adduced at the

guilt phase of trial, of the probability

of the defendant's future dangerousness

was substantial, and the comments'

potential for prejudice was at best

minimal. Accordingly, we hold that the

prosecutor's comments do not entitle

O'Bryan to federal habeas relief.

V. PAROLE

INSTRUCTIONS.

Under Texas law, a

jury may not consider the possibility of

parole in its deliberation on punishment,

see, e.g., Moore v. State, 535 S.W.2d

357 (Tex.Cr.App.1976), and the jury in

O'Bryan's case was so instructed.

The defendant maintains that the trial

court's refusal to instruct the jury

about the law governing the Board of

Pardons and Paroles in relation to

inmates sentenced to life imprisonment

deprived him of a fundamentally fair

trial in violation of the due process

clause of the fourteenth amendment.

Relying on People v.

Morse, 60 Cal.2d 631, 388 P.2d 33, 36

Cal.Rptr. 201 (1964), O'Bryan argues

that an instruction about the law of

parole is necessary in a capital case to

dispel the widely held misconception

that a life sentence will result in a

defendant's only serving nine or ten

years in prison. The Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals declined to adopt the

view of the California courts that a

jury should be charged on the law of

parole and then instructed not to

consider it. O'Bryan, supra, 591 S.W.2d

at 478.

As in our review of

alleged prosecutorial misconduct, our

review of a challenge to instructions

given in a state criminal trial is

narrowly limited to whether the alleged

impropriety "so infected the entire

trial that the resulting conviction

violates due process." Cupp v. Naughten,

414 U.S. 141, 147, 94 S.Ct. 396, 400, 38

L.Ed.2d 368 (1973); accord, Easter v.

Estelle, 609 F.2d 756, 758 (5th

Cir.1980); Higgins v. Wainwright, 424

F.2d 177 (5th Cir.1970). Morse, supra,

was a response to California's earlier

minority position permitting the jury to

consider parole in determining

punishment. Concluding that the evidence

concerning parole introduced at trials

was confusing to the jurors, the

California Supreme Court decided that a

jury should be informed about the parole

law and then told not to consider parole

in making its determination on

punishment.

The California

court's decision was based on its

supervisory powers over the state trial

courts, not on the United States

Constitution. Whatever the reasons for a

state court's decision to require such

an instruction in its own trial courts,

we cannot say that an instruction on

parole is constitutionally mandated in a

capital case. See California v. Ramos,

--- U.S. ----, ----, 103 S.Ct. 3446,

3448, 77 L.Ed.2d 1171 (1983) (instruction

informing jurors in capital case that

governor has power to commute "life

sentence without possibility of parole"

but not informing them of equivalent

power to commute death sentence not

unconstitutional).

Since the failure to

give such an instruction did not deprive

O'Bryan of a fundamentally fair trial,

his complaint about the court's