Appeal From Circuit Court of Jackson County, Hon.

David W. Shinn

Stephen N. Limbaugh, Jr., Judge

Opinion

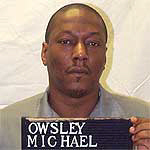

A Jackson County jury convicted Michael Owsley of

first degree murder, kidnapping, and two counts of armed criminal

action for which he was sentenced to death and consecutive terms of

life, fifteen years, and fifteen years, respectively. Owsley's

motion for post-conviction relief was dismissed for noncompliance

with Criminal Procedure Form No. 40 as required in Rule 29.15.

Because the death sentence was imposed, this Court has jurisdiction

of the appeal. Mo. Const. art. V, sec. 3. We affirm the

conviction and sentence on all counts as well as the dismissal of

the post-conviction relief motion.

I. FACTS

The evidence at trial, which we review in the

light most favorable to the verdict, State v. Storey,

901 S.W.2d 886, 891 (Mo. banc 1995), reveals the following:

On April 18, 1993, Elvin Iverson, the murder

victim in this case, drove from Kansas City, Missouri, to Junction

City, Kansas, to sell drugs. Iverson was accompanied by Ellen Cole.

When the two returned to the house in Kansas City

where Iverson was staying, defendant Owsley and a codefendant named

Hamilton confronted them and ordered them to lie on the ground. Both

Iverson and Cole complied on observing that Hamilton carried a Tech-9

semi-automatic weapon with a silencer and Owsley carried a 12-gauge

sawed-off shotgun.

Hamilton then demanded to be told "where the

[drug] money was." Iverson pleaded that he did not have the money

and that he had given it to another person who had accompanied him

to Junction City. After Hamilton pressed unsuccessfully for more

information, Owsley spoke directly to Iverson, calling him "a

thorough nigger" and saying that "you're [Iverson] begging for your

life now, nigger."

Owsley backed up his malicious comments by

punching and kicking Iverson and, at times, beating his face with

the sawed-off shotgun. When Iverson continued to deny that he had

any money, Owsley then took a bag from Hamilton and began smothering

Iverson.

At that point, Hamilton asked Cole about the

money, and in response, she lied by offering to take them to a key.

Hamilton then tied Cole and Iverson together by their feet with an

electrical extension cord, and either he or Owsley covered them with

a blanket.

Owsley stood over them, hitting them with the

barrel of the shotgun and said, "One of you live; one of you die."

He put the gun to Iverson's head, but before he could fire, Hamilton

instructed him to place a pillow over Iverson's head. After putting

the pillow in place, Owsley pulled the trigger, killing him

instantly.

In making their getaway, the two gunmen untied

Cole and took her along. Owsley forced her into Hamilton's car, and

as Hamilton drove away, Owsley followed in another car. A short time

later, Cole managed to escape from Hamilton's car and notify the

police.

II. ALLEGATIONS OF PRETRIAL ERROR

A. Irreconcilable Conflict with Counsel

Owsley first claims that the trial court erred in

denying his several motions to dismiss counsel and substitute new

counsel. The motions were based on alleged irreconcilable conflict

between Owsley and his lawyer. Denial of the motions, Owsley

explains, deprived him of his constitutional right to effective

assistance of counsel. Alternatively, Owsley claims that at minimum,

substitute counsel should have been appointed for the October 17,

1994, hearing on the motion to dismiss counsel because Owsley's

counsel actively opposed some of the factual allegations in the

motion.

A trial court's ruling on a motion to dismiss

counsel is a legitimate exercise of its discretion and will not be

disturbed on appeal unless there is clear abuse of discretion,

State v. Hornbuckle, 769 S.W.2d 89, 96 (Mo. banc 1989),

and "the appellate court will indulge every intendment in favor of

the trial court." Id.

To "prevail on a claim of irreconcilable

differences with counsel, the defendant must produce objective

evidence of a 'total breakdown in communication.'" State v.

Parker, 886 S.W.2d 908, 929 (Mo. banc 1994), citing

Hornbuckle, 769 S.W.2d at 96. Proof of a total

breakdown in communication is established, according to Owsley, not

only by the interaction between the two, but also by counsel's

statements to others and counsel's ineffective assistance throughout

the proceedings.

The colorable claims within the wide array of

counsel's alleged misconduct includes: failing to furnish Owsley

with copies of the police reports, to meet and consult with him, and

to discuss his defense; failing to pursue all of the investigation

that Owsley requested; speaking condescendingly to Owsley; breaching

the attorney-client privilege by telling another client about

Owsley's case and characterizing Mr. Owsley as a liar; calling

Owsley a "pain in the ass;" commenting to a newspaper and on radio

that death penalty cases are not processed as expeditiously as they

should be; commenting in an objection to the prosecution's voir dire

questions about prior criminal experiences that if he did the same,

"we will be here for two weeks;" telling the venire panel that "[w]e're

not drinking, playing cards and drinking rum, which we would rather

being [sic] doing;" asking a venire panel member whether he could

consider both life imprisonment and death if Owsley were found

guilty; stating to the venire panel that "I don't like [experts]

personally," even though he intended to rely on one.

None of Owsley's claims are well taken. To the

extent that the "irreconcilable differences" were born of counsel's

alleged misconduct at trial, Owsley's remedy was to present the

claims in a properly filed Rule 29.15 motion. Obviously, the trial

court should not be expected to discharge and replace counsel during

the course of the trial itself. The one other claim cognizable in a

post-conviction relief action is counsel's alleged failure to fully

investigate the case.

This matter was fully addressed by the trial

court during one of the pretrial hearings on Owsley's motion to

discharge counsel. After considering Owsley's position, the court

concluded that the information Owsley sought to investigate was

irrelevant to the issues in the case and then warned Owsley that he

would waste his counsel's time for legitimate trial preparation if

he continued to send him on "wild goose chases." From our review of

the record, the court was correct in this determination.

The claims that relate more directly to a "breakdown

in communication" are also insufficient to establish irreconcilable

conflict. From the motion hearings before the court and on the face

of the motions themselves, Owsley made it clear that he was in fact

still communicating with his lawyer.

The essence of his complaints, instead, was that

he simply was not pleased with the tone and content of his lawyer's

comments and criticism. As the court found after allowing Owsley to

fully air his concerns, the comments and criticisms to which Owsley

objected, and his resulting displeasure, was the product of Owsley's

own uncooperativeness with his lawyer. Owsley is not permitted to

generate an "irreconcilable conflict" through his own misconduct.

See Hornbuckle, 769 S.W.2d at 97.

Even though Owsley himself was the cause of the

problem, the court nonetheless took the exemplary step to alleviate

the stress of the situation by appointing co-counsel to assist in

Owsley's defense. Having provided Owsley co-counsel with whom Owsley

could presumably communicate, the court did all and more than was

required. The point is denied.

Owsley's alternative claim that he was

effectively unrepresented at the October 17, 1994, hearing on his

motion to discharge his lawyer, fares no better. During the hearing,

Owsley presented his lengthy handwritten motion to his lawyer who

read it to the court, after which Owsley himself addressed the court

at length. When Owsley had finished, his lawyer contested some of

the allegations Owsley had made about him and their interaction in

preparing for trial. When a dispute of this sort arises, it is the

court's responsibility to inquire into the matter, and the

defendant's lack of legal training is immaterial. United

States v. Blum, 65 F.3d 1436, 1441 (8th Cir. 1995).

Moreover, the defendant Owsley in this case has

not shown how he was prejudiced. From our review of the record, it

is clear that Owsley made all the points he sought to make on the

question of irreconcilable conflict, and he does not claim otherwise.

By conducting a full hearing on the matter to inquire about the

allegations, Owsley's interests were sufficiently protected.

B. Speedy Trial Rights Violated

Owsley also claims that the trial court erred in

denying his numerous motions to dismiss for lack of a speedy trial.

Owsley was arrested and placed in jail on April 22, 1993, but was

not brought to trial until October 18, 1994, roughly eighteen months

later. This delay, he contends, violates speedy trial guarantees

under the United States and Missouri Constitutions as well as

sections 545.780, 545.890, and 217.460, RSMo 1994.

The United States Supreme Court mandates a

balancing of four factors when determining whether a defendant's

constitutional right to a speedy trial was violated. Barker v.

Wingo, 407 U.S. 514, 533 (1972). The factors include the "[l]ength

of delay, the reason for the delay, the defendant's assertion of his

right, and prejudice to the defendant." Barker, 407

U.S. at 530.

In this case, the dispositive factors are those

pertaining to the reason for the delay and the prejudice to the

defendant. The eighteen month delay was mostly attributable to the

various actions taken by defendant or on his behalf, which included

requests for a continuance, a second medical examination by various

other experts, a change of judge, and additional counsel.

The only delays attributable to the State

resulted from its requests for the initial competency exam and

extension of time for the exam to be completed. The State in no way

attempted to delay the trial, while in contrast, a great deal of

time was spent handling Owsley's motions. For these reasons alone

there is no constitutional violation.

The prejudice factor also weighs against the

defendant. To establish prejudice, Owsley states that the eighteen

month delay between arrest and trial "precipitated the need for [counsel]

to request a mental examination . . . [that] was then necessary

because Mr. Owsley had expressed the desire to plead guilty and be

sentenced to death." He also maintains that the delay caused him to

become despondent.

Despite these developments, Owsley does not

demonstrate how they affected the trial and disposition of his case,

and from our review of the record, we find that no prejudice

resulted. In addition, Owsley claims that the lengthy delay

exacerbated the tension between his counsel and him, which then

culminated in the irreconcilable conflict. Having determined that

there was no irreconcilable conflict, this point is meritless. In

sum, Owsley's failure to show prejudice also defeats his claim of a

constitutional violation.

Reliance on sections 545.780 and 545.890 --

Missouri's speedy trial statutes -- is also meritless. Application

of section 545.780 is dependent on the finding of a constitutional

violation. Because we have already found that Owsley was not denied

his constitutional right to a speedy trial, the statute provides him

no relief. Section 545.890 does not apply if "the delay shall happen

on the application of the prisoner." Sec. 545.890. Because the delay

in this case was largely due to actions taken by Owsley, this

section affords him no relief either.

In a final point, Owsley argues that section

217.460 requires that a case be brought to trial within 180 days.

This section is a part of the Uniform Mandatory Disposition of

Detainers Law that applies to intrastate detainers. As discussed

above, Owsley was responsible for nearly all of the delays. The

delays that he caused tolled the 180 day requirement. See

State ex rel. Clark v. Long, 870 S.W.2d 932, 940-42 (Mo. App.

1994); Smith, 686 S.W.2d at 547-48. Point denied.

C. Suppression of Confession

Owsley next asserts that the trial court erred

when it denied both a motion to suppress and a motion to reconsider

suppressing his confession on grounds that his confession was

involuntary. Specifically, Owsley claims that he only implicated

himself after the police interrogating him promised not to seek the

death penalty.

A confession that becomes part of the basis of a

conviction must be voluntary or else the defendant is denied due

process. Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368, 376 (1964).

It is the State's obligation to prove, by a preponderance of the

evidence, that a confession was voluntarily given. State v.

Feltrop, 803 S.W.2d 1, 12 (Mo. banc 1991).

The test of voluntariness is whether, under the

totality of the circumstances, the "defendant was deprived of a free

choice to admit, to deny, or to refuse to answer, and whether

physical or psychological coercion was of such a degree that

defendant's will was overborne at the time he confessed."

State v. Lytle, 715 S.W.2d 910, 915 (Mo. banc 1986). Review

of a trial court's ruling on a motion to suppress is to determine

only if the decision was supported by substantial evidence,

Feltrop, 803 S.W.2d at 12, and "[t]hat there is evidence

from which the trial court could have arrived at a contrary

conclusion is immaterial." Id.

The record in this case shows that five people --

Owsley, his mother, the prosecuting attorney, and the two police

officers who questioned Owsley -- testified at the suppression

hearings. The prosecuting attorney and the police officers all

testified that they made no offer of leniency and that they never

stated that the death penalty had been "waived."

This testimony, regardless of evidence to the

contrary, was substantial evidence that amply supported the court's

finding that no offers had been made to induce Owsley's confession.

Therefore, the trial court did not err when it overruled Owsley's

motion to suppress.

III. ALLEGATIONS OF TRIAL ERROR

A. Guilt Phase

1. Intoxication Evidence

Owsley complains that his right to due process

was violated when he was prohibited under section 562.076.3, RSMo

1994, from introducing during the guilt phase evidence of his

alleged intoxication. Evidence of his intoxication from alcohol and

drugs, he submits, would have negated the requisite mental state of

deliberation.

In the alternative, he claims that Instruction

No. 12, based on MAI-Cr3d 310.50 -- the voluntary intoxication

instruction -- should not have been submitted to the jury. The

instruction, he alleges, violated his right to due process, because

it relieved the State of proving all of the elements of the crime.

Moreover, he claims that the limited evidence of his consumption of

alcohol -- evidence that was admitted on other grounds -- did not

support the submission of Instruction No. 12.

The introduction of voluntary intoxication

evidence is severely restricted by section 562.076.3, that states:

Evidence that a person was in a voluntarily

intoxicated or drugged condition may be admissible when

otherwise relevant on issues of conduct but in no event shall it

be admissible for the purpose of negating a mental state which

is an element of the offense. In a trial by jury, the jury shall

be so instructed when evidence that a person was in a

voluntarily intoxicated or drugged condition has been received

into evidence.

Because defendant made no clear or direct

challenge to this statute either at trial or in his motion for new

trial, he has not preserved the issue for review. Refusing the

admission of Owsley's intoxication evidence did not constitute

manifest injustice; therefore, we decline to undertake plain error

review.

Owsley's alternative claim, while preserved for

appeal, has no merit. Instruction No. 12 accurately tracks MAI-CR

310.50, which reflects this Court's decision in State v. Erwin,

848 S.W.2d 476 (Mo. banc 1993), and the subsequent statutory change

to section 562.076. See sec. 562.076; MAI-CR 310.50.

As this Court has already decided, MAI-CR 310.50 does not relieve

the State of its burden of proving all of the elements of a crime,

State v. Taylor, 944 S.W.2d 925, 936 (Mo. banc 1997);

thus, it did not violate defendant's due process rights.

To support the submission of Instruction No. 12,

there need only be evidence that a person was voluntarily

intoxicated. See sec. 562.076; MAI-CR 310.50, Notes on

Use. In this case, evidence of Owsley's voluntary intoxication --

that he drank a pint and a half of gin before committing the murder

-- was admitted through the testimony of Detective Cridlebaugh and

the dialogue on the video taped confession. This evidence was more

than sufficient. Accordingly, the instruction was properly given to

prevent that evidence from being used to negate Owsley's mental

intent. See Taylor, 944 S.W.2d at 936. The point is

denied.

2. Autopsy Report Evidence

Next, Owsley argues that Dr. Berkland, the

medical examiner of Jackson County, should not have been allowed to

testify as to the findings of another doctor who performed the

autopsy on the victim, Mr. Iverson. Owsley contends that such

testimony is hearsay because the performing doctor was available to

testify.

The record, however, shows that Dr. Berkland did

not testify about the performing doctor's opinion but instead

testified as an independently qualified expert who based his own

opinions on the factual information in the autopsy report. In

State v. Taylor, 944 S.W.2d 925 (Mo. banc 1997), this Court

found no error where the same Dr. Berkland testified, after an

independent review of autopsy photographs, about the position of

entry and exit wounds on the victim. Id. at 939. This

case is essentially no different. The point is denied.

3. Reasonable Doubt Definition

Owsley argues that in both the guilt and the

penalty phases of the trial, the definition of "reasonable doubt"

submitted to the jury was error because it used the phrase "firmly

convinced," which does not satisfy due process concerns. This Court

has repeatedly rejected this argument. See, e.g., State v.

Brown, 902 S.W.2d 278, 287 (Mo. banc 1995); State v.

Chambers, 891 S.W.2d 93, 105 (Mo. banc 1994). Point denied.

B. Penalty Phase

1. Mitigating Evidence

Owsley claims that he should have been allowed

during the penalty phase to introduce sixteen photographs depicting

scenes from his childhood. The trial court excluded all but one

picture on relevancy grounds. In the penalty phase, a "defendant is

allowed to introduce any evidence that may mitigate the

penalty imposed." State v. Whitfield, 837 S.W.2d 503,

512 (Mo. banc 1992). More particularly, relevant mitigating evidence

includes that which refers to "the defendant's background or

character or to the circumstances of the offense that mitigate

against imposing the death penalty." Penry v. Lynaugh,

492 U.S. 302, 318 (1989). The pictures in this case, however, do not

show that Owsley came from a disadvantaged background or that he had

good character, and they depict nothing relating to the offense in

question. Moreover, they were cumulative to the oral testimony of

his penalty phase witnesses. The trial court did not abuse its

discretion in excluding this evidence. The point is denied.

2. Closing Argument

Owsley argues that during the penalty phase

closing argument, the State 1) misstated the law concerning the use

of mitigating circumstances, 2) engaged in improper personalization,

and 3) resorted to impermissible name calling, all of which require

a new penalty phase hearing.

For his first point, Owsley cites the following

comments:

The next thing you must do is you must go on.

And Instruction No. 22, there are the mitigating circumstances,

and you must consider each one of these six mitigating

circumstances. You must consider whether any of those six even

come close to outweighing this. Do they outweigh this to the

extent that you believe, that you all must believe that one

of those mitigating circumstances outweigh those circumstances

that you have found beyond a reasonable doubt, outweigh that to

the extent that he should be serving life imprisonment without

possibility of parole instead of getting a death sentence. (emphasis

added)

Owsley did not object to this comment at trial;

thus, this point will be reviewed for plain error only. State

v. Parker, 886 S.W.2d 908, 927 (Mo. banc 1994); Rule 30.20.

Standing alone, the State's comment might create some confusion, but

the actual instruction given was exceedingly clear:

If you decide that one or more aggravating

circumstances exist to warrant the imposition of death, as

submitted in Instruction No. 19, each of you must then

determine whether one or more mitigating circumstances exist

which outweigh the aggravating circumstance or circumstances so

found to exist.

The clarity of the actual instruction prevented

any possible manifest injustice or miscarriage of justice. Therefore,

we have no discretion to grant plain error relief. State v.

Simmons, No. 77368 (Mo. banc 1997), slip op. at 6; Rule

30.20.

The claims of personalization and name calling

derive from the prosecutor's additional comments:

Should you show him more mercy than he showed

to Elvin Iverson? What have we seen that says there's a reason

to do that? Because we have seen a picture of him as a child?

Every brutal murderer starts off as a child. You know, we see

this and our hearts go out, hearts go out to mother, and she

tries to go to you saying you, as women, you have to understand

me as mothers. Don't kill my child. Of course, Mr. Iverson's

mother didn't have the opportunity to beg like that, and we

all love our sons and daughters, and we all hope for them they

will grow up to be something other than a monster like Michael

Owsley. We hope they will do something with their lives. (emphasis

added)

The passage emphasized above was not

impermissible personalization because it did not "suggest personal

danger to the jurors or their families." State v. Kreutzer,

928 S.W.2d 854, 876 (Mo. banc 1996); State v. Storey,

901 S.W.2d 886, 901 (Mo. banc 1993). Additionally, it was not

prejudicial name calling. Although name calling is strongly

discouraged, it is not prejudicial where there is evidence to

support such a characterization. State v. Clemmons,

753 S.W.2d 901, 908 (Mo. banc 1988); State v. Burke,

719 S.W.2d 887, 891 (Mo.App. 1986); State v. Munoz,

678 S.W.2d 834, 835 (Mo.App. 1984) (where the State presented

overwhelming evidence that the defendant sodomized his nine year old

son, no plain error for State to refer to him as a "monster" in

closing argument). Given the manner in which Owsley dispatched his

victim, to characterize him as a "monster" is not inapt. The trial

court, therefore, committed no error.

IV. POST-CONVICTION RELIEF UNDER RULE 29.15

(FN1)

After sentencing, Owsley timely filed a pro se

Rule 29.15 motion. He was then appointed counsel who filed an

amended Rule 29.15 motion and a motion to disqualify the judge for

cause. The motion court judge overruled the motion to disqualify and

then dismissed the amended Rule 29.15 motion because it did not

comply with Criminal Procedure Form 40.

A. Disqualification of Judge

Owsley claims that the denial of his motion to

disqualify the judge violated his right to due process and to be

free from cruel and unusual punishment. In post-conviction relief

motions, "the movant may disqualify a judge on the due process

ground that the judge is biased and prejudiced against the movant."

Haynes v. State, 937 S.W.2d 199, 202 (Mo. banc 1996).

However, the bias or prejudice must stem from a source outside the

proceedings and "result in an opinion on the merits on some basis

other than what the judge learns from participation in the case."

Id.

In this case, the bias of which Owsley complains

is that the judge had a definite extrajudicial, approving opinion of

the quality of work performed by Owsley's trial counsel. The sole

evidence of this bias consists of the judge's comments during the

hearings on Owsley's motion to discharge his counsel. At those

hearings, the judge stated nothing more than that counsel enjoyed a

reputation as one of the best criminal defense lawyers in Kansas

City and that he had recently convinced a jury in another capital

murder case to spare the defendant's life.

These statements reflecting the judge's

professional respect for counsel do not establish that the judge

would be biased in ruling on the effectiveness of counsel's

performance in this case. Furthermore, the judge disposed of the

Rule 29.15 proceedings on the basis of appellant's counsel's

noncompliance with Form 40; thus, the judge was not required to rule

on the merits of trial counsel's performance. The point is denied.

B. Form 40 Compliance

Owsley next complains that the trial court

improperly imposed the requirements of Criminal Procedure Form 40 to

his amended Rule 29.15 motion. Rule 29.15 requires expressly that

any relief sought pursuant to 29.15 shall substantially follow

Criminal Procedure Form 40. Rule 29.15(b). The reason for requiring

compliance with Form 40 when seeking relief under 29.15 is "to

provide not only the state but also the trial court, and the

appellate court on review, with an orderly and concise statement of

the grounds on which movant bases his request for post-conviction

relief." State v. Katura, 837 S.W.2d 547, 553 (Mo. App.

1992).

Paragraph 8 of Form 40 directs the movant to

state "concisely all the grounds known to you for vacating, setting

aside or correcting your conviction and sentence." Paragraph 9 then

requires a concise statement of "the facts which support each of the

grounds set out in (8), and the names and addresses of the witnesses

or other evidence upon which you intend to rely." Once counsel is

appointed, "[i]f the motion does not assert sufficient facts . . .

counsel shall file an amended motion that sufficiently alleges the

additional facts and grounds." Rule 29.15(e); see White v.

State, 939 S.W.2d 887, 893 (Mo. banc 1997).

With respect to the amended motion, the trial

court made the following "Conclusions of Law":

The court takes judicial notice of the fact

that movant's amended motion is 96 pages long. Not only is this

motion not concise, it is not even remotely in the form of Form

40. Sections III through X seem to contain movant's grounds for

relief, however, the facts necessary to support these

allegations appear to be contained in section II. Section II is

entitled Chronological Narrative of Rights Violations Revealed

in the Record and that is precisely what it contains. Movant has

listed excerpts from both the trial and pre-trial transcripts in

chronological order. These entries have little or no explanation

as to what 29.15 allegations they are meant to support and[, to]

add to the confusion those sections of the amended motion that

purport to contain movant's grounds for relief, when any factual

support is offered at all, refer generally to point 6. which is

the list of chronological rights violations. It appears to the

court that after examining movant's grounds in sections III

through X it must go through this point 6 and find factual

support for each allegation on its own. As already discussed,

one of the purposes of the requirements of form 40 is to provide

the trial court with a convenient format for reviewing movant's

allegations and, as already discussed movant's amended motion

does not come close to meeting the requirements of form 40 or

Rule 29.15

Based on these conclusions, the trial court

entered an order that "movant's amended motion for relief is

overruled in its entirety as it does not comply with the conciseness

requirement of Supreme Court Rule 29.15." Having independently

reviewed the amended motion, this Court agrees with the trial

court's determination. The amended motion violates Paragraphs 8 and

9 of Criminal Procedure Form 40 and as such mandates dismissal.

Nevertheless, Owsley argues that the requirements

of Form 40 should not have been imposed on him because compliance is

only required under Rule 29.15(b), pertaining to original, pro se

motions, and thus compliance is not required for amended motions

authorized under Rule 29.15(f). However, Rule 29.15, taken as a

whole, clearly requires any and all requests for relief under the

Rule to conform substantially to Form 40. Rule 29.15(b).

Moreover, because of the special purpose of a

Rule 29.15 motion -- to achieve finality in criminal proceedings --

exceptions should be disfavored. See White, 939 S.W.2d

at 893 (noting that 29.15 motions are collateral attacks and will be

honored, but must be balanced with the goal of bringing finality to

criminal process and conserving "scarce public resources");

Smith v. State, 798 S.W.2d 152, 153 (Mo. banc 1990) (stating

"[o]f sole significance is the fact that this Court's rules for

postconviction relief make no allowance for excuse," when time

limits were not followed). Indeed, Owsley's counsel had no reason to

believe the Form 40 requirements would not be followed. In

State v. Katura, 837 S.W.2d 547 (Mo. App. 1992), decided

three years before Owsley's amended motion was filed, the Court of

Appeals dismissed a "rambling, vague and prolix" amended motion of a

mere 40 pages (less than half of the size of Owsley's amended

motion), because it did not comply with Paragraphs 8 and 9 of Form

40. Katura, 837 S.W.2d at 553.

In a fall-back position, Owsley alleges that the

motion court should have honored his request to hold a Rule 62.01

conference before dismissing the amended motion. Under Rule 62.01,

the court, in its discretion, may convene a conference to address

any confusion in the presentation of motions in civil cases. However,

as the State aptly noted, a conference to "facilitate the orderly

consideration of Mr. Owsley's claims" -- as requested by Owsley --

flies in the face of Rule 29.15 itself; the claims are supposed to

be orderly in the first instance and should require no "facilitation."

The motion court did not abuse its discretion on this point.

Owsley's related complaints that the motion court

neither held an evidentiary hearing nor entered findings of fact and

conclusions of law as required under Rule 29.15 must be denied as

well. These requirements apply only when a Rule 29.15 motion has

been perfected by compliance with Form 40.

C. Possible Abandonment

In view of the dismissal of the amended motion,

Owsley next argues that he was abandoned by his counsel, and that

the 29.15 court should have conducted a "Luleff"

abandonment hearing. Abandonment hearings have been required by this

Court to determine the cause of 1) counsel's failure to file an

amended motion, Luleff v. State, 807 S.W.2d 495, 498

(Mo. banc 1991); 2) counsel's failure to have the amended motion

verified, State v. Bradley, 811 S.W.2d 379, 384 (Mo.

banc 1991); and 3) counsel's failure to file the amended motion in a

timely fashion. Sanders v. State, 807 S.W.2d 493, 495

(Mo. banc 1991).

In this case, Owsley's post-conviction counsel

filed a timely and verified amended motion. The fact that its poor

content and structure resulted in its dismissal does not mean that

Owsley was abandoned. His abandonment claim is nothing more than a

claim of ineffective assistance of post-conviction counsel, which is

"categorically unreviewable." State v. Hunter, 840 S.W.2d

850, 871 (Mo. banc 1992); see also Pollard v. State,

807 S.W.2d 498, 502 (Mo. banc 1991). The point is denied.

V. PROPORTIONALITY REVIEW

Finally, Owsley contends that the death sentence

is improper because this Court will not engage in a meaningful

proportionality review. Particularly, he claims 1) that this Court

does not afford adequate notice with a meaningful opportunity to be

heard on the proportionality issue, 2) that this Court does not

maintain a complete database of cases as required by section 565.035

because cases in which life sentences are imposed are not included,

and 3) that the sentence in this case is excessive and

disproportionate. The purpose of the proportionality review, as this

Court has repeatedly explained, is merely to prevent freakish and

wanton applications of the death penalty. State v. Parker,

886 S.W.2d 908, 933 (Mo. banc 1994). The review performed

sufficiently meets that standard. See State v. Ramsey,

864 S.W.2d 320, 328 (Mo. banc 1993); see also

Zeitvogel v. Delo, 84 F.3d 276, 284 (8th Cir. 1996) (upholding

this Court's proportionality review).

The process for the review has been clearly

stated in the statute and in past cases, and its repetition offers

no precedential value. See Parker, 886 S.W.2d at

933-34, Ramsey, 864 S.W.2d at 328. Additionally, any

due process claims, such as the ones Owsley brings here, have

already been rejected by this Court. State v. Weaver,

912 S.W.2d 499, 522 (Mo. banc 1995). Claims contesting the adequacy

of the database as a factor in the proportionality review have also

previously been rejected. Parker, 886 S.W.2d at 933;

Whitfield, 837 S.W.2d 503, 515 (Mo. banc 1992). Thus,

Owsley's only remaining point is the proportionality of his crime to

the death sentence.

After careful review of the record, this Court

holds that the trial court's imposition of the death sentence did

not result from the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other

arbitrary factor. See section 565.035.3(1). The jury

unanimously found four statutory aggravators: 1) that Owsley was

convicted of a prior aggravated robbery and assault; 2) that the

victim was murdered for money; 3) that the murder involved torture

and depravity of the mind, and was outrageously and wantonly vile,

horrible, and inhuman; and 4) that the murder was committed during a

burglary and attempted robbery. The finding of these aggravators is

amply supported by the evidence.

The death sentence in this case is neither

excessive nor disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar

cases. Owsley ambushed his victims, bound their feet together,

demanded to know where the money was, beat the victims, played a

game with their lives, and finally murdered one of them with a

shotgun blast to the head. Defendants in similar cases who torture

and execute someone while perpetrating a crime on that person are

often sentenced to death. State v. Smith, 944 S.W.2d

901, 925 (Mo. banc 1997); State v. Whitfield, 939 S.W.2d

361, 372 (Mo. banc 1997); State v. Tokar, 918 S.W.2d

753 (Mo. banc 1996); State v. Oxford, 791 S.W.2d 396,

402 (Mo. banc 1990); State v. Kilgore, 771 S.W.2d 57

(Mo. banc 1989); State v. Griffin, 756 S.W.2d 475 (Mo.

banc 1988); State v. Murray, 744 S.W.2d 762 (Mo. banc

1988); State v. Walls, 744 S.W.2d 791 (Mo. banc 1988);

State v. Foster, 700 S.W.2d 440 (Mo. banc 1985);

State v. Gilmore, 681 S.W.2d 934 (Mo. banc 1984);

State v. Johns, 679 S.W.2d 253 (Mo. banc 1984); State

v. Lashley, 667 S.W.2d 712 (Mo. banc 1984); State v.

Gilmore, 661 S.W.2d 519 (Mo. banc 1983); State v. Laws,

661 S.W.2d 526 (Mo. banc 1983). Point denied.

VI. CONCLUSION

The judgments of conviction and sentence, and the

dismissal of the Rule 29.15 motions are affirmed.

All concur.

Footnotes: