(270 Ga. 745)

(514 SE2d 639)

(1999)

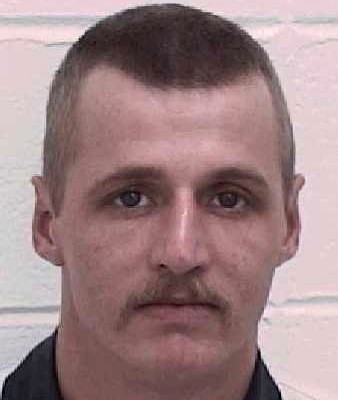

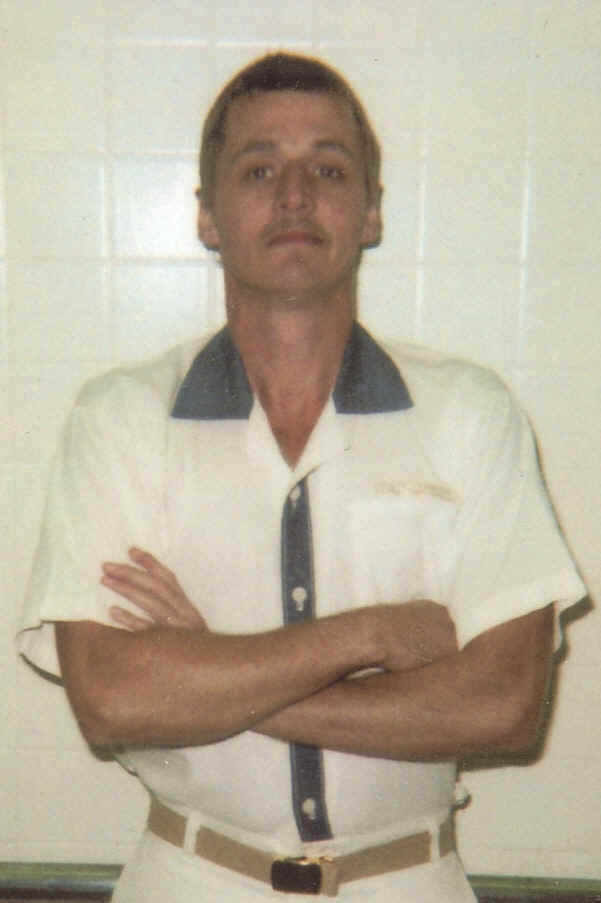

SEARS, Justice.

Murder. Lumpkin Superior Court. Before Judge Stone.

1. The evidence shows that in April 1992 Myrtle

Ricketts was renting two trailer homes on her property, one to Tammy

Lovell and one to Vicky Gottschalk. Ms. Gottschalk lived with her

ten-year-old daughter, Wendy Nicole Vincent. Ms. Lovell lived with

her two young sons. Pruitt is Lovell's ex-husband and in early April

1992 Lovell and Pruitt were attempting a reconciliation; Pruitt

sometimes stayed the night at his ex-wife's trailer.

At about midnight on April 9, 1992, Pruitt

arrived at Lovell's trailer. He was drunk and violent and he and

Lovell got into an argument. Lovell told him she did not want him

there. At about 1:15 a.m., Pruitt angrily left, punching Lovell's

porch light as he was leaving and cutting his hand. Pruitt was

wearing blue jeans, a flannel shirt, and Reebok tennis shoes.

At about the same time, Ms. Gottschalk left her

home to work a night shift; her daughter remained sleeping in her

trailer. The trailers share a common driveway and Gottschalk had to

wait for Pruitt to pull out first.

Shortly thereafter, Lovell looked out her window

and saw a man she assumed was Pruitt unscrewing the porch light on

the Gottschalk trailer. She looked away to attend to a sick child

and, when she looked out again, the area was dark.

At about 3:00 a.m., Pruitt entered a convenience

store and asked to use the bathroom. The clerk recognized Pruitt

because he was a regular customer, but she did not know his name.

Pruitt had blood on him, but the clerk testified that this was not

unusual because Pruitt was a chicken catcher and chicken catchers

usually have blood on them. Pruitt was in the bathroom for about ten

minutes, and then left the store.

At about 3:45 a.m., Pruitt returned and went back

into the bathroom for five minutes. He emerged, stared at the clerk

while she helped another customer, and then left. When the clerk

checked the bathroom shortly thereafter, paper towels and Comet were

strewn about, and the water had been left running. She testified

that only Pruitt had used the bathroom since she cleaned it. A

friend of Pruitt testified that he called her at 3:00 or

3:30 a.m. and told her he needed to talk because he had "done

something bad." She told him he could not come over because her

child was sick.

Pruitt returned to his ex-wife's trailer and she

let him in. He undressed, leaving the clothes he had been wearing in

a pile, and showered. At about 6:30 a.m., Ms. Gottschalk returned

home and found her daughter lying dead on the bedroom floor. Wendy

had been stabbed several times and her throat was cut.

The medical examiner also testified that there

was trauma to her vagina and anus. Semen stains on the bed indicated

that the assault began there and the victim was then moved to the

floor and killed. Ms. Gottschalk screamed for help and Pruitt and

Lovell came over. Pruitt knelt beside the victim's body and felt for

her pulse; he was not wearing the clothes he had worn the night

before.

Because neither trailer had a phone, Lovell went

to Ms. Ricketts's house to call the police. When Lovell and Ricketts

returned to the Gottschalk trailer, Ricketts saw Pruitt reach up and

screw the porch light bulb until the light came on. She did not see

him try the switch first.

The police became suspicious of Pruitt due to the

description of his movements during the last few hours, and because

he had scratches and cuts on his hands. Lovell consented to a search

of her trailer and the police noticed bloodstains on the clothes

Pruitt had been wearing the previous night. Pruitt was arrested.

A broken window screen at the Gottschalk trailer

indicated the assailant's entry point, and beneath the window inside

the trailer was a vinyl chair containing a partial shoe print. A

State expert determined that this shoe print matched Pruitt's

Reeboks.

Type O blood was found on the jeans and shirt

that Pruitt had been wearing the night of the murder, and on the

steering wheel cover in his car. At the Gottschalk trailer, type A

blood was found on the porch light bulb, the screen door latch, and

near the entry window. Pruitt is type A and the victim was type O.

Inside the victim's bedroom, hairs consistent

with Pruitt's head hair were found on the bedroom floor, a bed sheet,

a pillow, and the victim's body, panties, socks and shirt. Hairs

consistent with Pruitt's pubic hair were found on the bed sheet and

the bedroom floor. Fibers found on the bed sheet microscopically

matched fibers from the jeans worn by Pruitt the night of the murder.

Gottschalk testified that Pruitt had never been a

guest in her home; the only time she had ever seen him in her

trailer was the brief time he felt for the victim's pulse on the

morning of April 10, 1992. Semen was discovered in the victim's anus

and DNA extracted from the semen matched Pruitt. The State's DNA

expert testified that the frequency of this DNA profile among

Caucasians is one in seven billion.

The evidence was sufficient to enable a rational

trier of fact to find Pruitt guilty of the crimes charged beyond a

reasonable doubt. The evidence was also sufficient to enable the

jury to find the existence of the statutory aggravating

circumstances beyond a reasonable doubt.

2. In 1996, the trial court ordered a change of

venue from Lumpkin County to Cherokee County. However, pursuant to

OCGA 17-7-150 (a) (3), the trial court

ordered that the jury would be selected from Cherokee County, but

that the trial would physically take place in Lumpkin County. Pruitt

complains that this procedure was found to be reversible error in

Hardwick v. State. In Hardwick, this Court held that Uniform

Superior Court Rule 19.2 (B), which provided for the trial of a case

in the county of venue with a jury selected from the transfer county,

conflicted with OCGA 17-7-150 (a) and

was therefore unenforceable. The Court stated that the General

Assembly "would have to enact legislation in order to allow [this

venue] procedure."

On July 1, 1995, the General Assembly did just

that, amending the statute to read, in part: "by the exercise of

discretion by the judge the trial jury may be selected from

qualified jurors of the transfer county, although the trial of the

criminal case may take place in the county of the venue of the

alleged crime." The trial court's order therefore does not violate

Hardwick and, since the statutory amendment shall apply "to all

criminal cases in which the county of transfer has not been

designated by court order," the trial court's 1996 venue order was

timely. OCGA 17-7-150 (a) (3) is also

not unconstitutional.

3. Pruitt complains that his constitutional right

to a speedy trial was violated. He was arrested in April 1992 and

not tried until September 1996, and he was incarcerated while

awaiting trial. However, the record reveals that much of the delay

is attributable to the defense, in that Pruitt repeatedly announced

that his experts were not ready for scheduled hearings or trial, and

he asked for a delay in the proceedings so that plea negotiations

could be conducted. Further, Pruitt did not assert his

constitutional right to a speedy trial until May 1996, and he never

asserted his statutory right to a speedy trial. Nor has Pruitt

brought forth evidence that the delay impaired his defense.

Accordingly, the trial court did not err by denying Pruitt's motion

to dismiss for lack of a speedy trial.

4. Before trial, Pruitt moved to exclude the

State's DNA evidence as unreliable under Caldwell v. State. At a

pretrial hearing, the State's DNA experts testified extensively

about the DNA testing procedures, probability calculations,

precautionary measures, standards, and protocol at the State Crime

Lab. Although the defense had its own DNA expert, Pruitt presented

no evidence to challenge the methodology of the tests or the results.

After viewing the evidence, we conclude that the trial court did not

err by ruling that the general scientific principles and techniques

involved in the DNA testing were valid and capable of producing

reliable results, and that the Crime Lab substantially performed the

scientific procedures in an acceptable manner. The DNA evidence was

admissible.

5. The indictment was based on legal and

sufficient evidence.

6. The Georgia statutes providing for the

imposition of the death penalty are not unconstitutional. The

Unified Appeal Procedure is also not unconstitutional. Execution by

electrocution is not cruel and unusual punishment.

7. There is no evidence that any cognizable group

was underrepresented in the Lumpkin County grand jury pool, or that

the method of selecting individual grand jurors was improper.

8. After the trial court ordered that the jury

would be selected from Cherokee County, Pruitt moved for a

continuance and for funds to hire an expert to conduct a study to

determine if the opinions of people aged 18-34 differed from the

opinions of people aged 35-44 in Cherokee County. The trial court

denied the motion for a continuance after finding that Pruitt knew

in May 1996 that a demographic study would take eight to ten weeks

and that Cherokee County was the transfer county, but waited until

July 1996 (eight weeks before trial) to request a continuance to

conduct the study. As a motion for expert assistance must be timely,

we conclude that the trial court's denial of the continuance was not

error.

In addition, the denial of funds to hire the

expert was not an abuse of discretion because, since there was no

evidence that young people were systematically excluded from the

traverse jury pool in Cherokee County, Pruitt failed to show why

such a study was critical to his defense. " 'The granting or denial

of a motion for appointment of expert witnesses lies within the

sound discretion of the trial court.' " We find no error.

9. The death qualification of prospective jurors

is not unconstitutional.

10. The trial court did not err by asking the

OCGA 15-12-164 voir dire questions to

the prospective jurors. Pruitt lacks standing to challenge the

constitutionality of the OCGA 15-12-164

(a) (4) question regarding conscientious objection to the death

penalty because "[t]he death qualification voir dire in this case

was more extensive and detailed than that provided by OCGA

15-12-164 (a) (4) and the record

indicates that no potential juror was excused from serving or

declared competent to serve based solely on his or her answer to the

(a) (4) statutory question."

11. Pruitt complains that the trial court

improperly restricted his voir dire of prospective jurors. We

disagree. "The scope of voir dire is largely left to the trial

court's discretion, and the voir dire in this case was broad enough

to ascertain the fairness and impartiality of the prospective jurors."

12. "The proper standard for determining the

disqualification of a prospective juror based upon his views on

capital punishment 'is whether the juror's views would prevent or

substantially impair the performance of his duties as a juror in

accordance with his instructions and his oath.' " "The relevant

inquiry on appeal is whether the trial court's finding that a

prospective juror is [or is not] disqualified is supported by the

record as a whole." A trial court's finding that a prospective juror

is or is not disqualified, including the trial court's resolution of

any equivocations or conflicts in the prospective juror's responses,

is given deference by an appellate court. "Whether to strike a juror

for cause is within the discretion of the trial court and the trial

court's rulings are proper absent some manifest abuse of discretion."

There are three prospective jurors Pruitt claims

should have been excused for cause due to their responses regarding

the death penalty. Although all three prospective jurors expressed a

strong preference for the death penalty, they also stated that they

could consider all the circumstances and both life and death as

possible sentences. Viewing the record as a whole and giving

deference to the trial court, we cannot conclude that the trial

court abused its discretion in qualifying these prospective jurors.

Pruitt also objects to the disqualification of four prospective

jurors due to their opposition to the death penalty. The record

reveals that these jurors all firmly and unequivocally stated that

they could not vote to impose a death sentence under any

circumstances. Therefore, the trial court did not abuse its

discretion by excusing these jurors for cause.

13. Pruitt complains about another prospective

juror who was excused for cause. That juror stated that the legal

system was unfair because he believed that his brother had been

convicted in an unfair trial where witnesses had lied. He said he

did not think he could lay aside the bias he felt against the State,

and that he might hold the State to a higher burden of proof. "Whether

to strike a juror for cause lies within the sound discretion of the

trial court," and we cannot conclude that the trial abused its

discretion in excusing this juror.

14. The written list of alleged statutory

aggravating circumstances was properly sent out with the jury in

accordance with OCGA 17-10-30 (c). It

was also not error for the trial court to decline to send a written

copy of the court's charge out with the jury.

15. Pruitt claims that the trial court erred in

denying his motion to suppress the out-of-court identification

evidence because Shirley Roach, the convenience store clerk who

identified Pruitt, was subjected to an impermissibly suggestive

photo lineup. Although there was conflicting evidence about how the

lineup was conducted and there was evidence that Ms. Roach saw

Pruitt's photograph in the newspaper before the lineup, we conclude

that there was no substantial likelihood of misidentification. Ms.

Roach repeatedly and unequivocally testified that Pruitt was a

regular customer who had been in her store many times, and that she

recognized his face but did not know his name. She knew that he was

employed as a chicken catcher, and even remembered that he used to

come into her store with his father. She testified that she did not

base her identification on the photos because, "I already knew him

from the store before. I didn't need to see no picture." She also

had reason to remember that he was in her store on the night of the

murder because he messed up the bathroom she had just cleaned.

16. Pruitt's contention that the shoe print

comparison evidence was unreliable and should have been suppressed

is without merit. The warrantless seizure of Pruitt's shoes, which

he was wearing when he was arrested, was proper.

17. Pruitt complains that the trial court erred

by denying his motion for adequate compensation of counsel. "However,

because there is not any proof that the alleged inadequate

compensation of counsel denied [Pruitt] effective assistance of

counsel, the attorney fee issue is not properly before us."

18. In August 1995, thirteen months before trial,

the trial court learned that the district attorney had hired

Pruitt's lead counsel, Robert Chandler, the previous month to

represent him in an unrelated personal matter. There is no evidence

that the district attorney intended to interfere with Pruitt's

representation when he hired Chandler. Although Chandler stated that

his representation of the district attorney would have no effect on

his representation of Pruitt, the trial court determined that this

relationship constituted a conflict. The trial court appointed

independent counsel to advise Pruitt, and a hearing pursuant to

United States v. Garcia was held in October 1995. At the Garcia

hearing, Pruitt was extensively advised about his Sixth Amendment

right to conflict-free representation, and questioned at length

about his understanding of this right. Pruitt waived his right to

conflict-free representation. However, in January 1996, Pruitt

changed his mind, and the trial court removed Chandler. In March

1996, the trial court appointed new lead counsel for Pruitt.

Pruitt complains that the hiring of his original

lead counsel by the district attorney caused an irreconcilable

conflict, and therefore reversible error, because it led to his

counsel's disqualification. The concurrent representation of a

defendant in a capital case and the district attorney seeking the

death penalty against the defendant is an obvious conflict.

However, without addressing the issue of waiver,

we conclude that Pruitt does not show any harm resulting from this

simultaneous representation. The conflict was resolved in January

1996 when the trial court removed Chandler, at the defendant's

request. New lead counsel was appointed for Pruitt six months before

trial, and Pruitt had the same co-counsel throughout his case. There

is no evidence that Chandler's performance was affected during the

simultaneous representation, or that his removal affected Pruitt's

representation at trial. In order to prevail on this claim, Pruitt

must show the existence of an actual conflict of interest that

adversely affected his lawyer's performance. Because Pruitt does not

show that the representation he received was deficient in any

respect, we find no error.

19. Based on Chandler's representation of the

district attorney outlined in the previous enumeration, Pruitt moved

to disqualify the district attorney due to conflict of interest and

appearance of impropriety. While we do not condone the actions of

the district attorney, this is not a situation where the prosecutor

previously represented the defendant, and there is no evidence that

the district attorney gained any information about Pruitt's defense

through his personal retention of one of Pruitt's attorneys. In fact,

Pruitt does not allege that Chandler divulged any information

acquired in the representation of Pruitt to the district attorney,

or that Chandler assisted the prosecution in any way. Therefore, we

find no error in the denial of the motion to disqualify the district

attorney.

20. The district attorney agreed to a consent

order that opened his file to the defense, and he announced at a

pretrial hearing that the defendant had been provided with

everything in the file, except for work product. About three weeks

before trial, the district attorney discovered a box of material

gathered during the investigation of the case and turned it over to

the defense. Pruitt claims prosecutorial misconduct in the failure

of the State to provide this material until the eve of trial. The

record reveals that this box was misplaced, and promptly turned over

to the defense when discovered. Moreover, the record shows that the

box was probably misplaced because it contained material that had

been deemed worthless to the investigation, such as soda cans taken

from the crime scene, a mold of Pruitt's teeth, the original

affidavits for the search warrants, a knife sheath, a flashlight

taken from Pruitt's ex-wife's car, and statements from EMTs who

arrived at the crime scene. Pruitt does not allege that there was

any evidence beneficial to the defense in this box, and nothing in

the box was used by the State at trial. As there is no evidence that

the State deliberately withheld evidence or that Pruitt was harmed

by the late disclosure of the box, we conclude that Pruitt was not

denied a fair trial due to prosecutorial misconduct.

22. While the jury was eating a meal during the

guilt-innocence phase, the assistant manager of the restaurant

entered their private dining area and said, "He is not guilty." The

bailiffs removed him. Upon notification of this incident, the trial

court questioned each juror. Every juror had heard the improper

comment, but all stated that they felt the comment was inappropriate

and that it would not affect their ability to be impartial. The

jurors also stated that there had been some discussion about the

stupidity of the man who had made the comment, but there had been no

discussion about the merits of the case. The trial court instructed

each juror on the presumption of innocence and the burden of proof.

When there is an improper communication to a juror, there is a

presumption of harm and the burden is on the State to show the lack

thereof. "However, where the substance of the communication is

established without contradiction, the facts themselves may

establish the lack of prejudice or harm to the defendant." The

evidence establishes that the improper communication in this case

did not affect the impartiality of the jurors, and the trial court

therefore did not err by denying Pruitt's motion for mistrial.

23. Pruitt claims that the jury saw him outside

the courtroom in shackles. When the defendant was being escorted

from the jail to the courtroom one morning, a van carrying the

jurors drove by. However, Pruitt was only a few feet outside the

doorway of the jail, and the sheriff saw the van coming and stepped

in front of Pruitt to obscure him. The trial court questioned each

juror and it is clear that no juror saw the defendant that morning.

Therefore, this contention is without merit.

24. The admission of pre-autopsy photographs of

the victim was not error.

25. The arrest warrant was valid.

27. Pruitt complains that the trial court erred

by denying his motion for a psychological evaluation during the

trial. At the beginning of the sentencing phase, Pruitt's counsel

requested a psychological examination for their client. They stated

that Pruitt was acting irrationally, but the trial court determined

that the sole basis for this claim was that Pruitt told his counsel

after conviction that he preferred a death sentence and would not

testify in mitigation. Upon questioning by the trial court, Pruitt

stated that he understood his decision, and knew his right to

testify and present mitigation evidence. The trial court noted there

had never been any indication that Pruitt was incompetent or had

mental problems, and it found that Pruitt's decision was made

knowingly and intelligently. After having been informed, a competent

defendant, and not his counsel, makes the ultimate decision about

whether to testify or present mitigation evidence. We conclude that

the trial court did not err by denying the motion for a

psychological examination during the trial.

28. The death sentence in this case was not

imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice, or other

arbitrary factor. The death sentence is also not disproportionate to

the penalty imposed in similar cases, considering both the crimes

and the defendant. The cases listed in the Appendix support the

imposition of the death penalty in this case as they involve a

deliberate murder during the commission of a rape or kidnapping with

bodily injury.

Darrell E. Wilson, District Attorney, Thurbert E.

Baker, Attorney General, Susan V. Boleyn, Senior Assistant Attorney

General, Beth A. Burton, Assistant Attorney General, for appellee.

Whelchel & Dunlap, Thomas M. Cole, Summer &

Summer, Chandelle T. Summer, Valpey & Walker, Gregory W. Valpey,

for appellant.