|

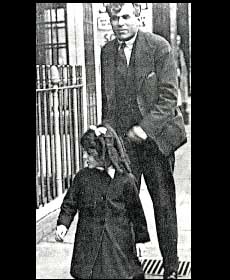

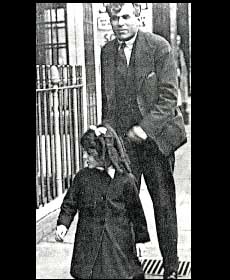

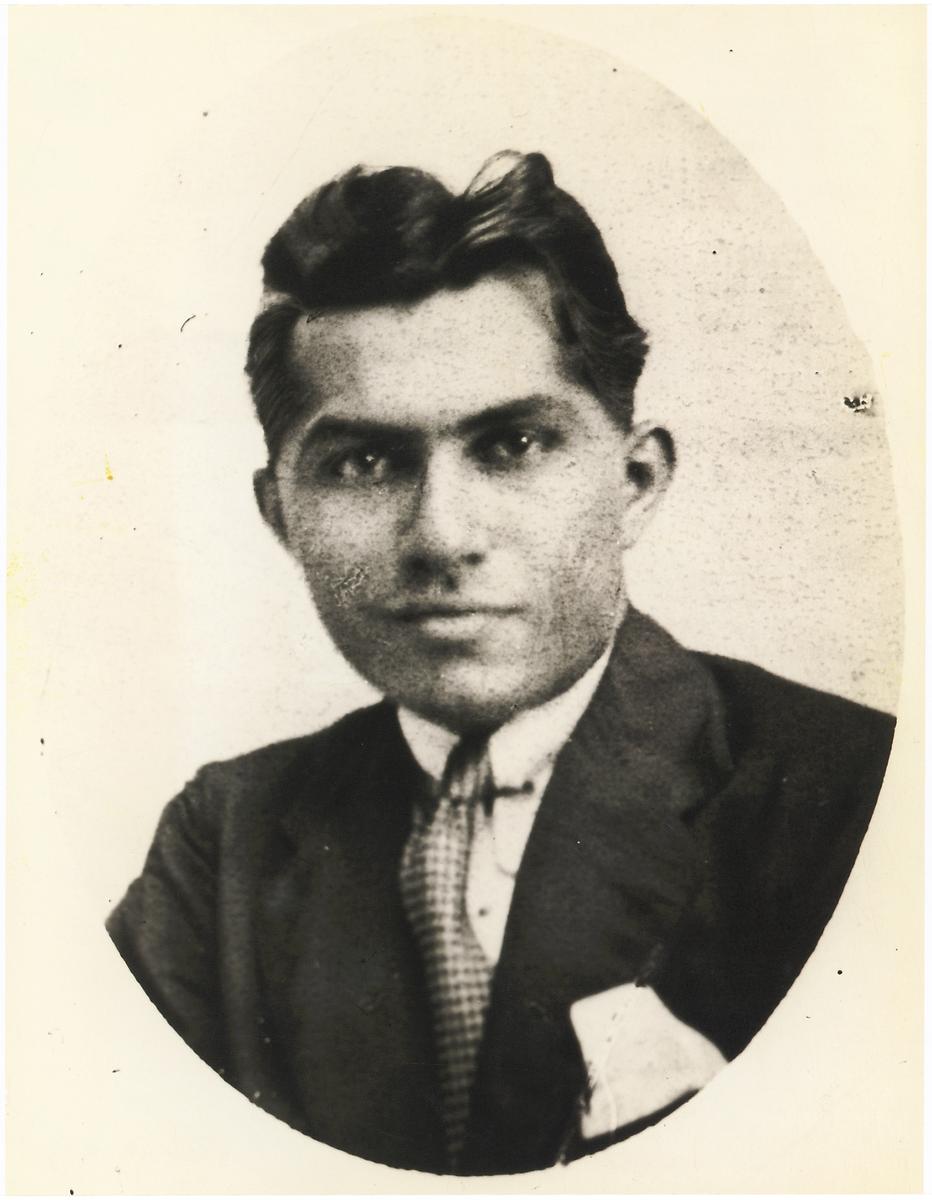

Dr. Buck Ruxton

Dr. Buck Ruxton

Neither Mrs. Ruxton nor

Mary Rogerson had been seen after September

14, 1935. Dr. Buck Ruxton, Isabella Ruxton's

husband and Mary Rogerson's employer, became

the prime suspect. Prior to her

disappearance, Dr. Ruxton had openly accused

his wife of unfaithfulness and threatened

her with violence. When first interviewed by

the police, he had a gash on his hand, was

agitated, and made inconsistent statements

about where his wife and nursemaid had gone.

(University of Glasgow)

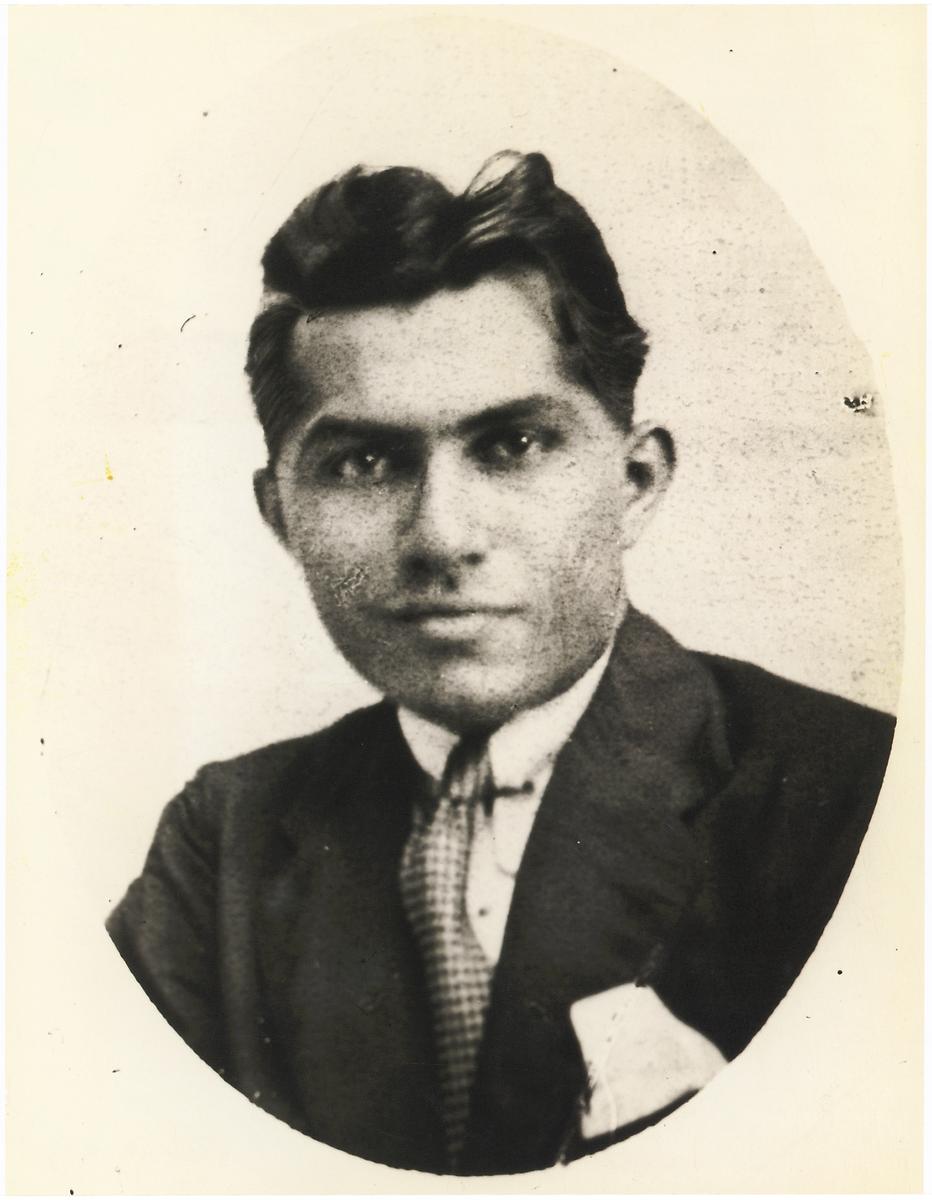

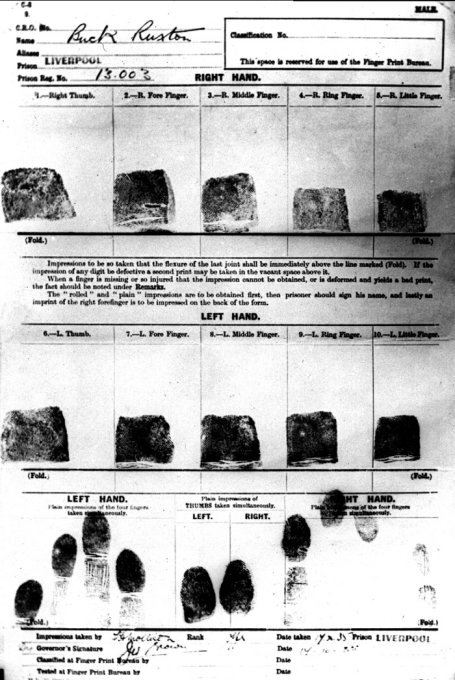

Buck Ruxton's Finger print form. Ruxton's

prints were taken in Liverpool Prison, 17 th

October, 1935.

(Image courtesy of Glasgow University

Archive Services)

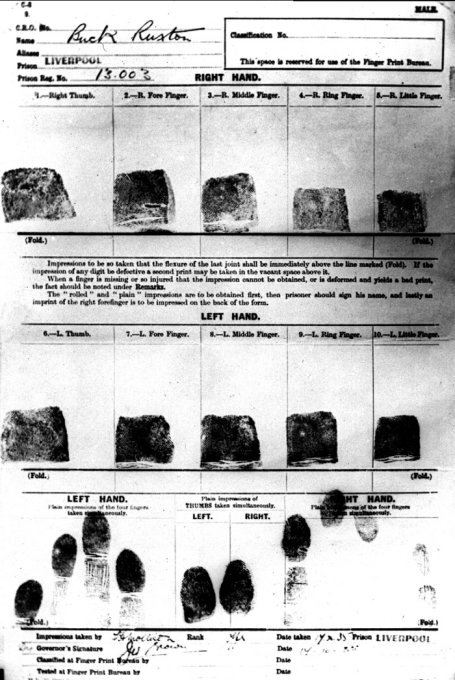

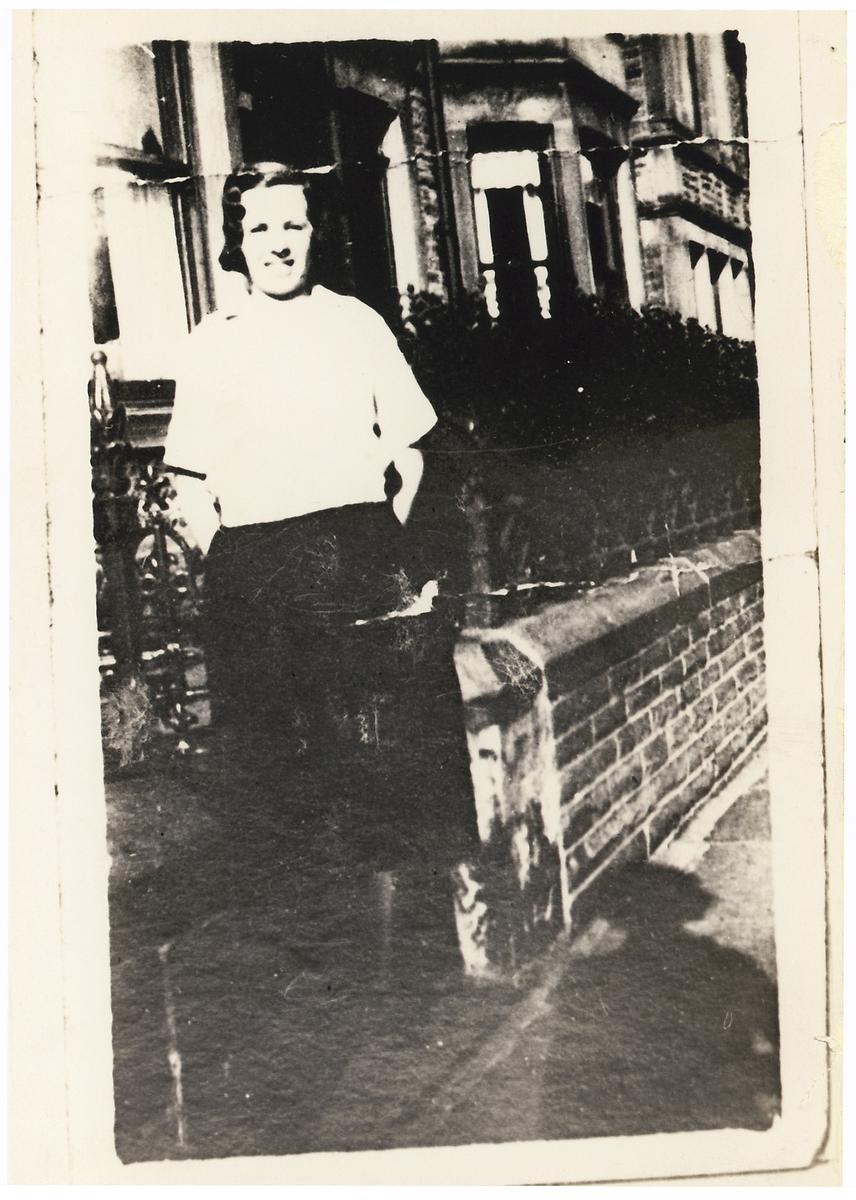

Mrs. Isabella Ruxton, 1935

Mrs. Isabella Ruxton Mrs.

Ruxton was last seen on September 14, 1935. Dr.

Ruxton claimed that she had

gone with Mary

Rogerson to Edinburgh, but her clothing was

still in the house and the car that she used

was

parked outside. (University of Glasgow)

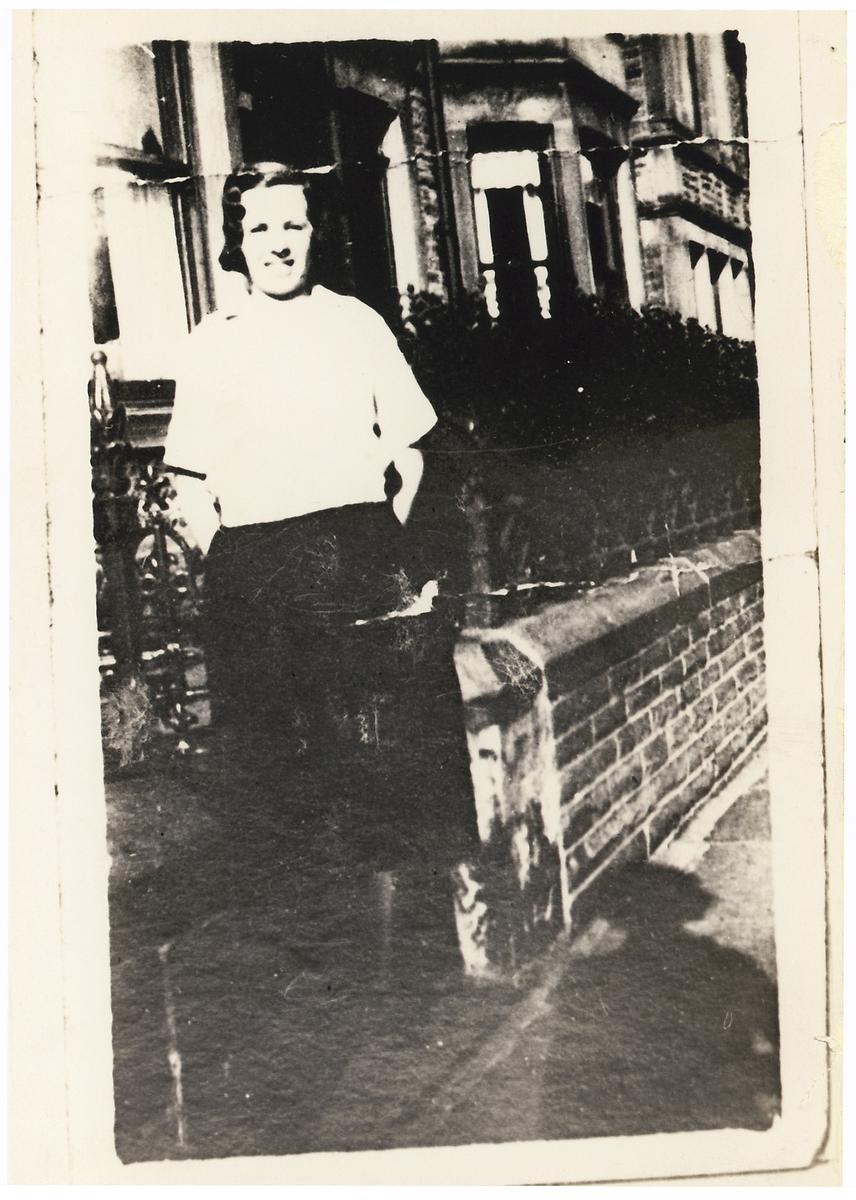

A nursemaid for the

Ruxton children, Mary Rogerson may have

been killed because she witnessed Mrs.

Ruxton's murder. Dr. Ruxton suggested to

the police that the two had left

together because Mary Rogerson was

pregnant and Mrs. Ruxton was helping her

obtain an abortion, which was then

illegal.

(University of Glasgow)

No. 2 Dalton Square was home

of Dr. Buck Ruxton.

(Michael Gradwell)

The bath from the house is now used as a horse trough at Hutton

Police HQ.

(Michael Gradwell)

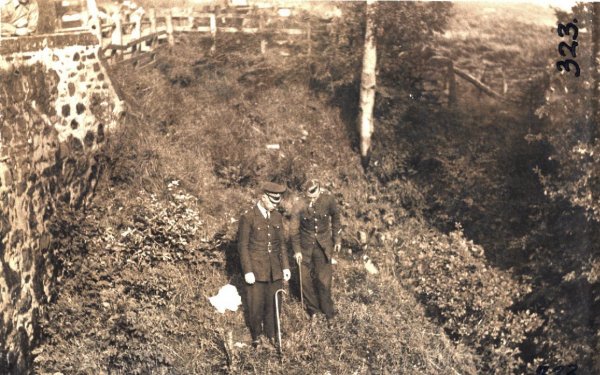

Police search for evidence in Moffat

(Image courtesy of Glasgow University Archive Services)

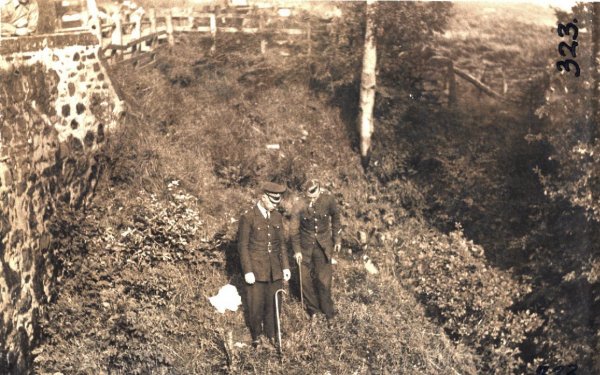

Detectives arrive in Moffat

l-r Supt. Adam Maclaren, Glasgow; Chief Constable W.

Black, Dumfriesshire; Assistant Chief

Constable Warnock,

Glasgow; Chief Constable A.N. Keith, Lanarkshire; Det.-Lieut.

Hammond,

finger print expert, Glasgow, and Det.-Lieut. Ewing,

Glasgow.

Police with remains bag.

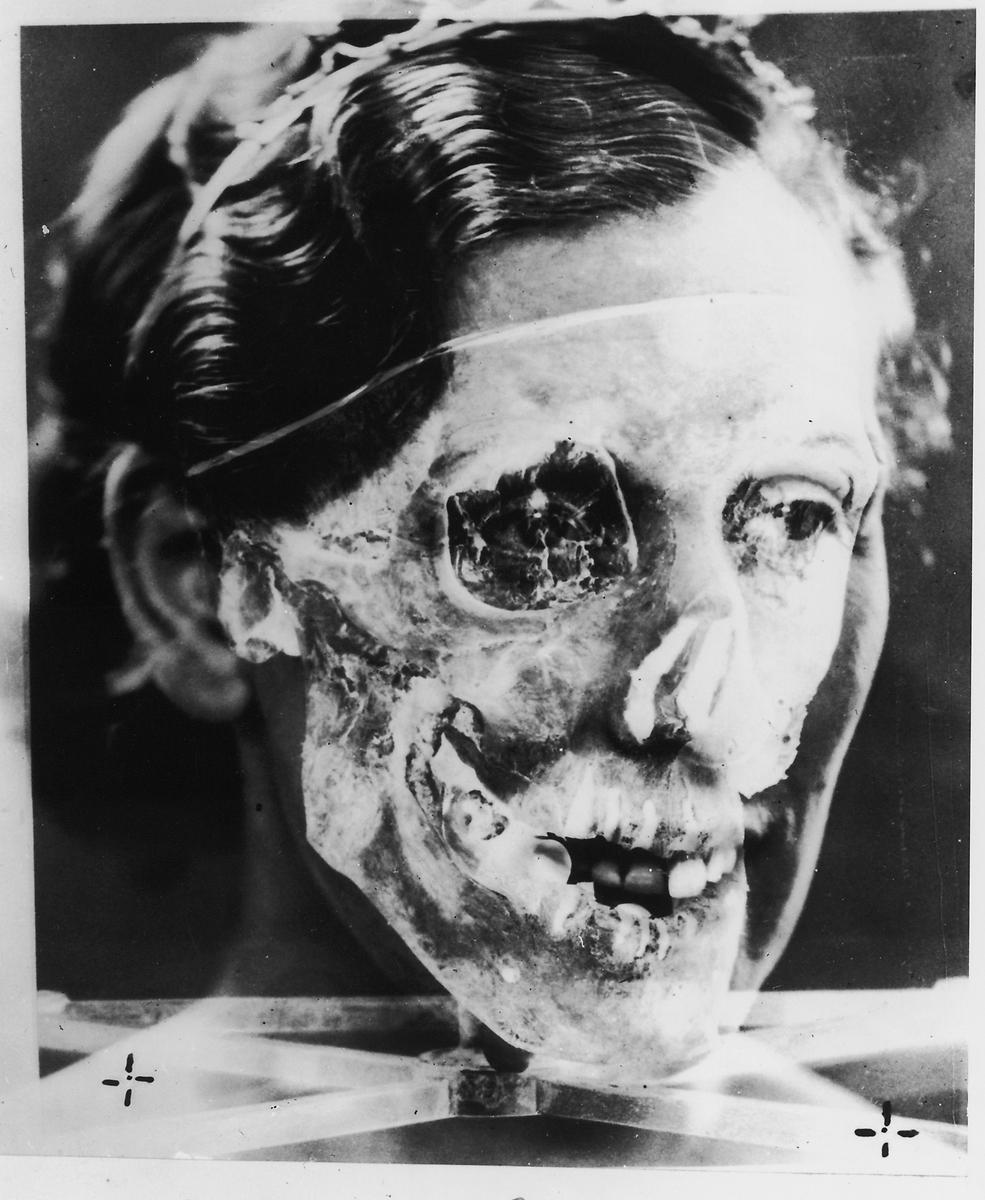

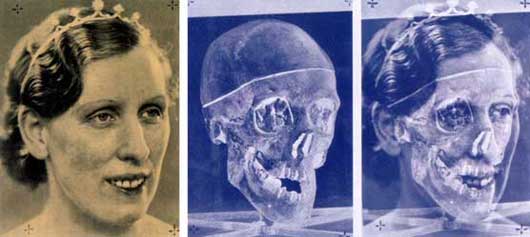

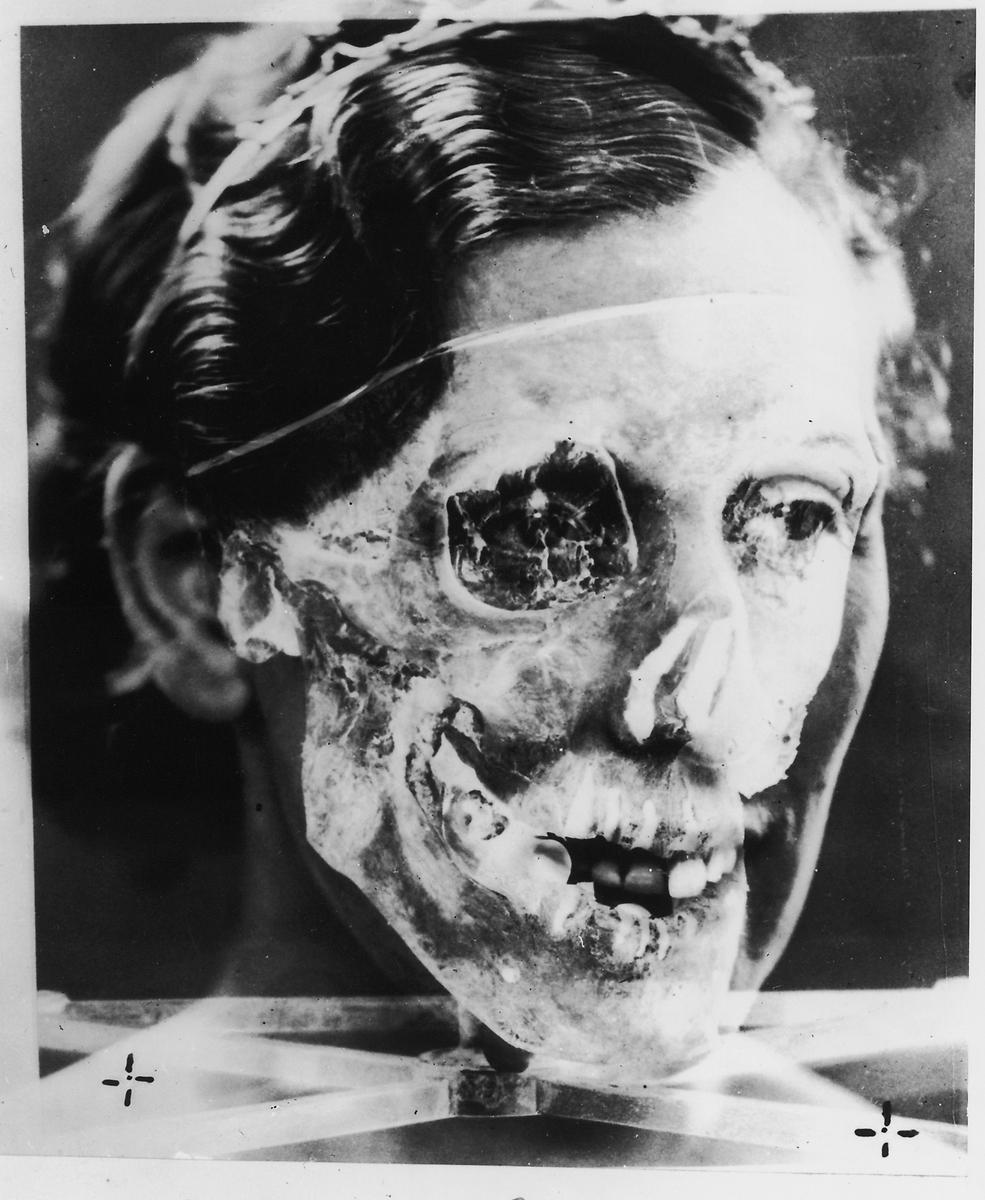

Skull no. 2, photograph B, 1935

Investigators photographed the Skull No. 2 in

the same orientation as an existing photograph of Mrs. Ruxton.

Then they laid a photo-transparency of this skull over the

portrait to establish that the skull was Mrs. Ruxton's.

(University of Glasgow)

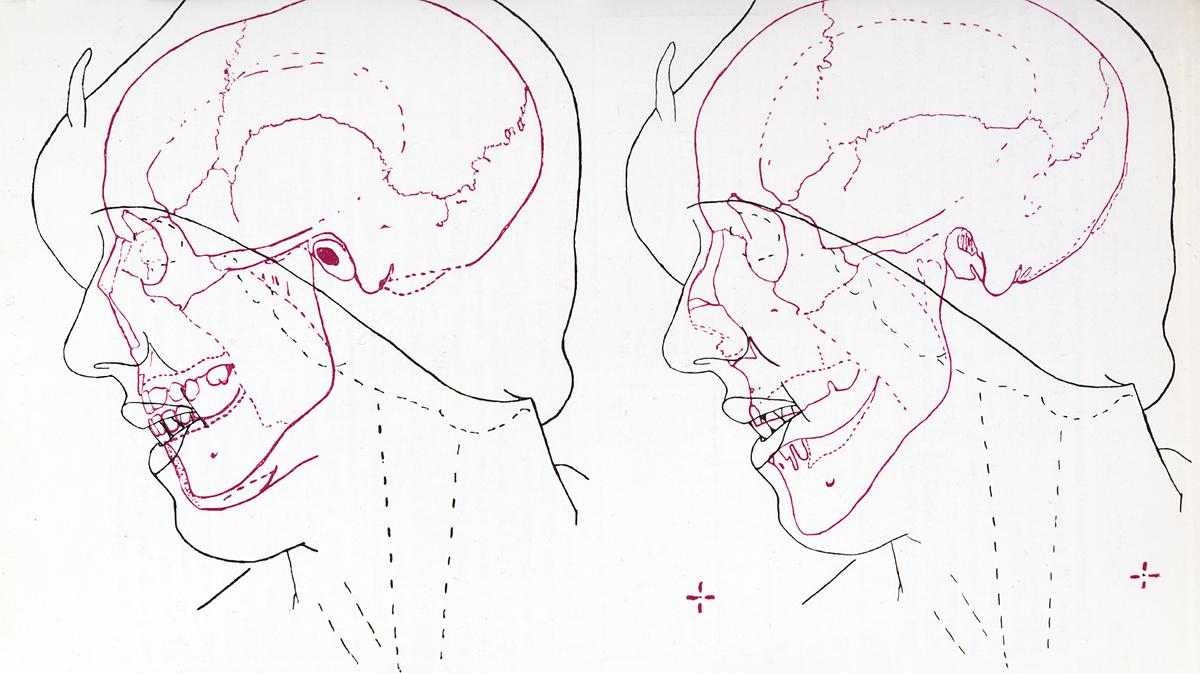

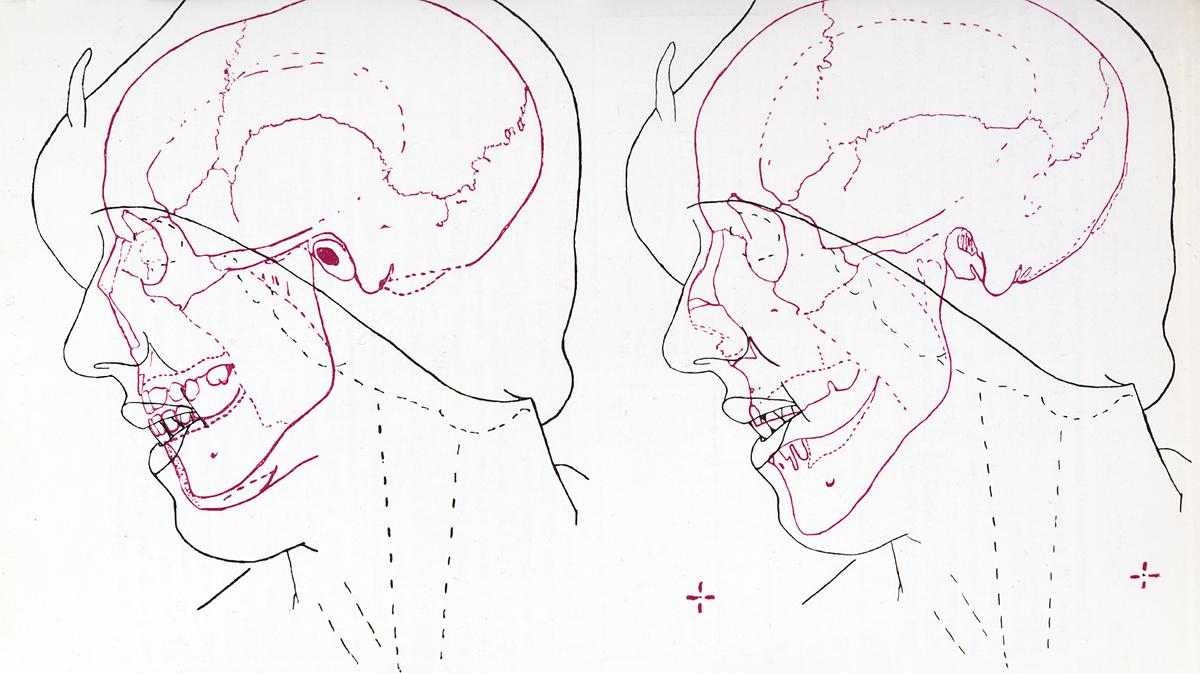

Superimposed outlines of Mrs. Ruxton

and two skulls for comparison, 1935

Outlines of Skull No. 1 superimposed

on outlines of Mrs. Ruxton's portrait. The facial

outlines do not correspond. Outlines of Skull No. 2

superimposed on outlines of Mrs. Ruxton's portrait. The

facial outlines seem to correspond. (University of Glasgow)

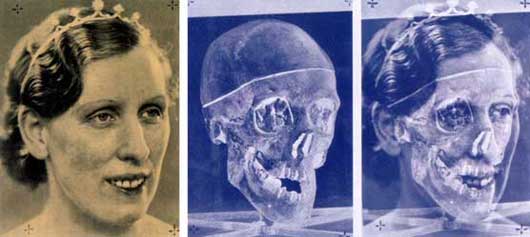

Superimposed photographs, Mrs. Ruxton and skull no.2, 1935

(University of Glasgow)

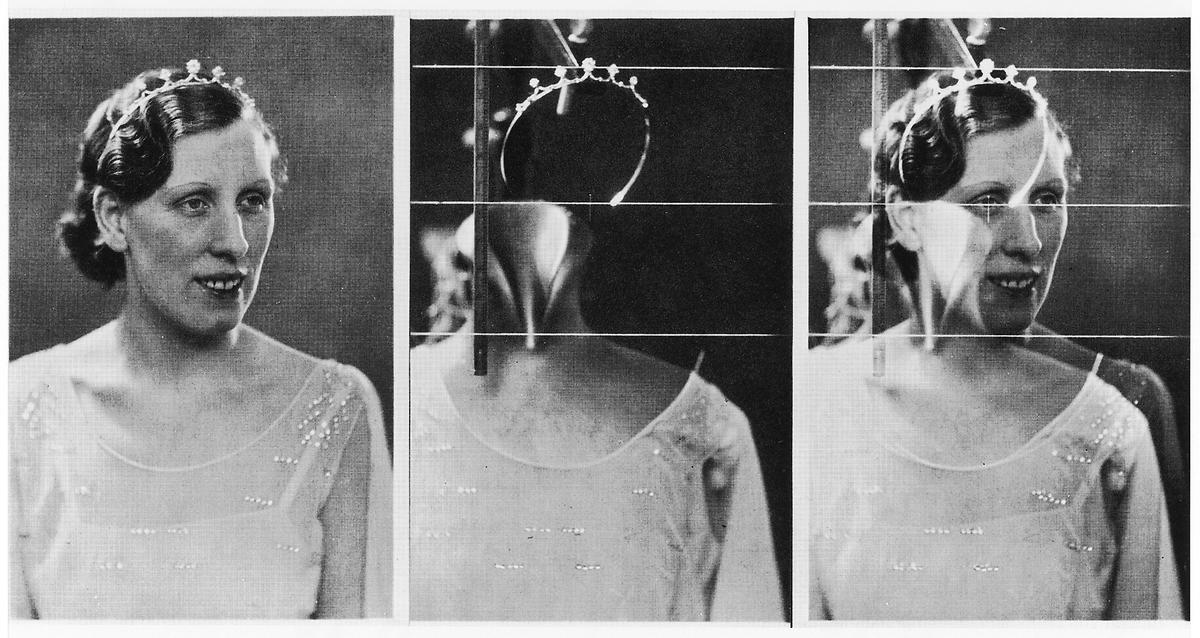

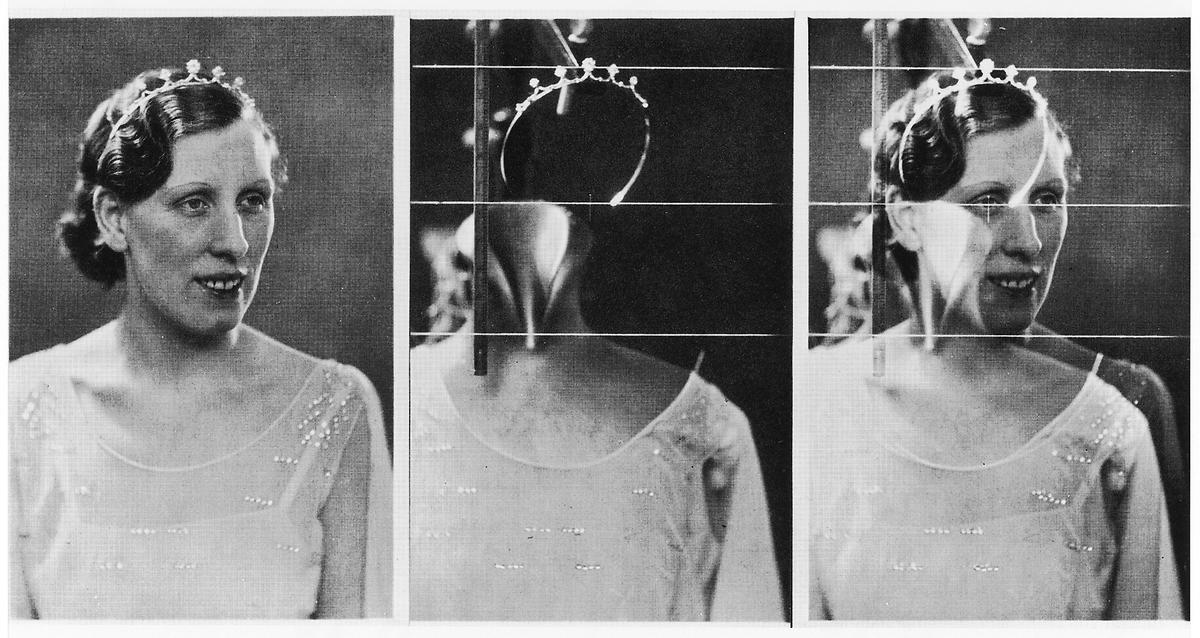

Mrs. Ruxton's portrait with dress

and tiara, 1935.

Finding the Scale: Photographic

reconstruction was an important tool in the

investigation. The skulls of the two victims were

compared with multiple existing portraits to confirm

the identifications. To find the precise scale of

this portrait, a photographer staged a measured shot

of the dress and tiara and superimposed them on the

portrait. (University of Glasgow)

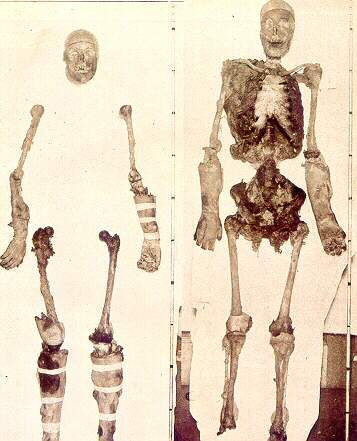

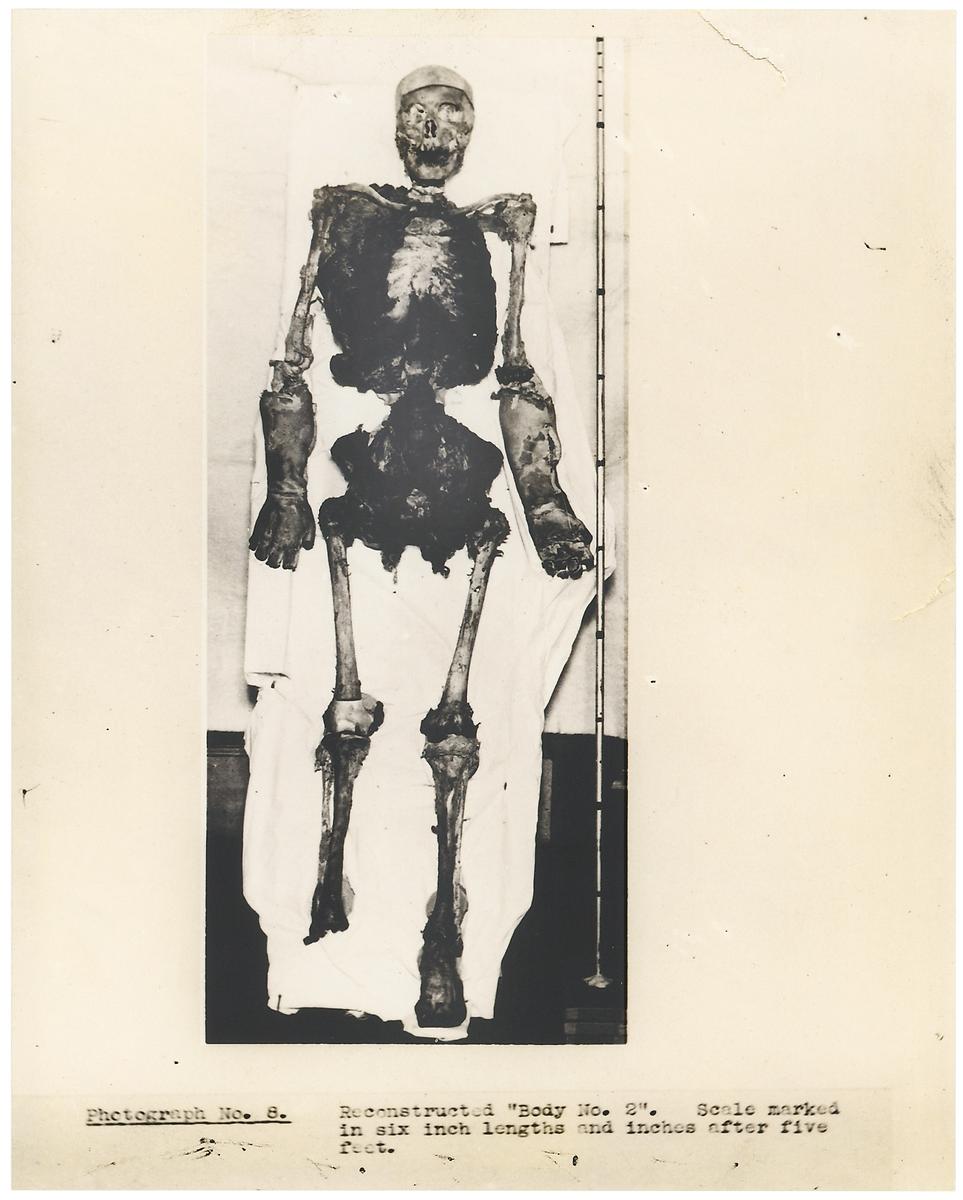

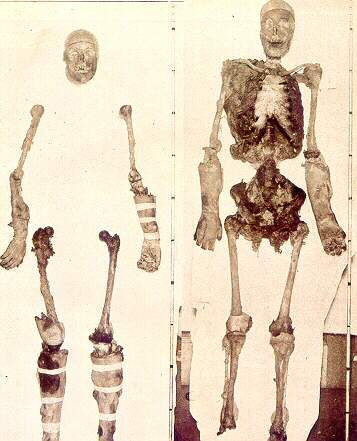

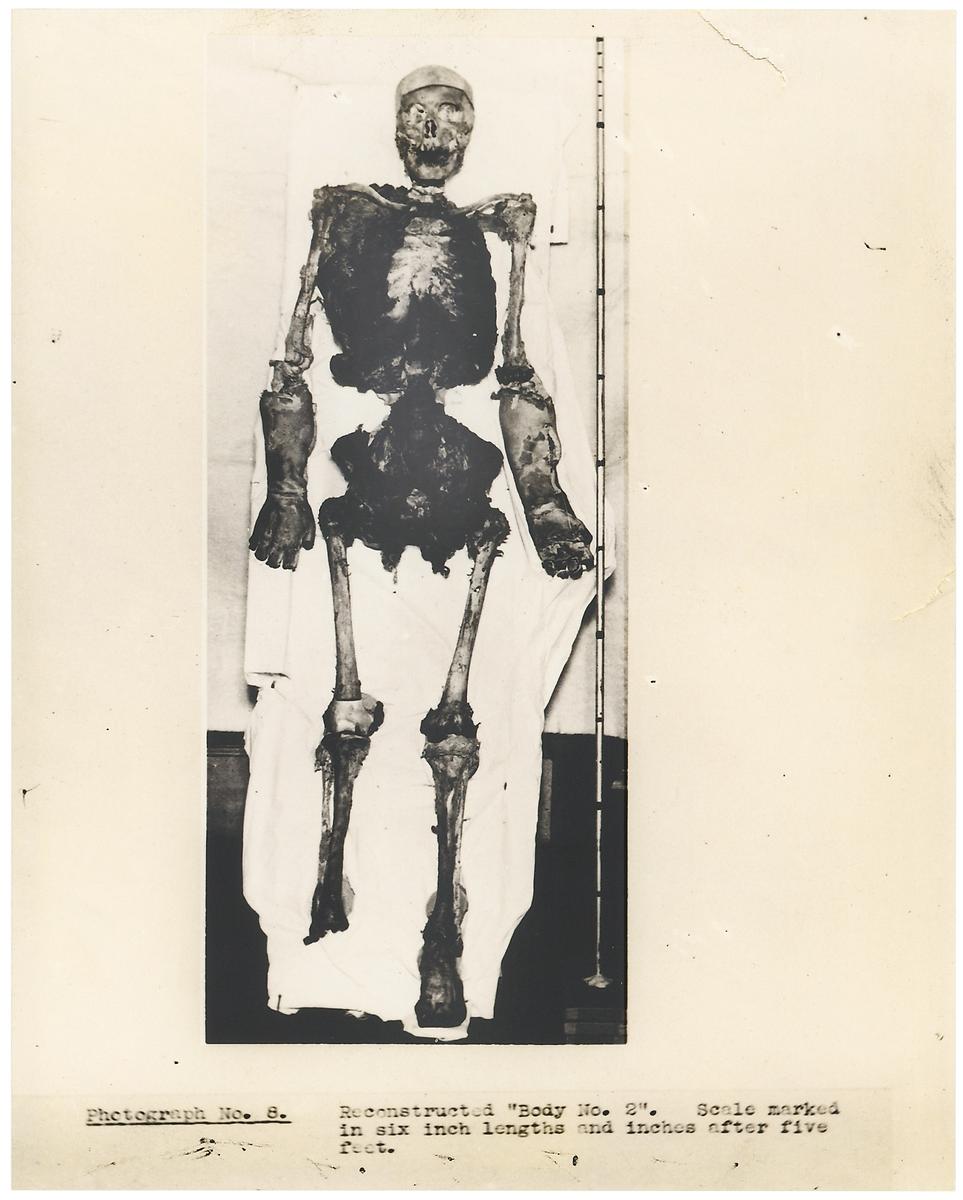

Mrs.

Ruxton reconstructed body

no. 2, 1935.

Reconstructing the Bodies:

Because the body parts of

the two victims were jumbled

and had to be reassembled,

newspapers called the case

the "Jigsaw Murders."

(University

of Glasgow)

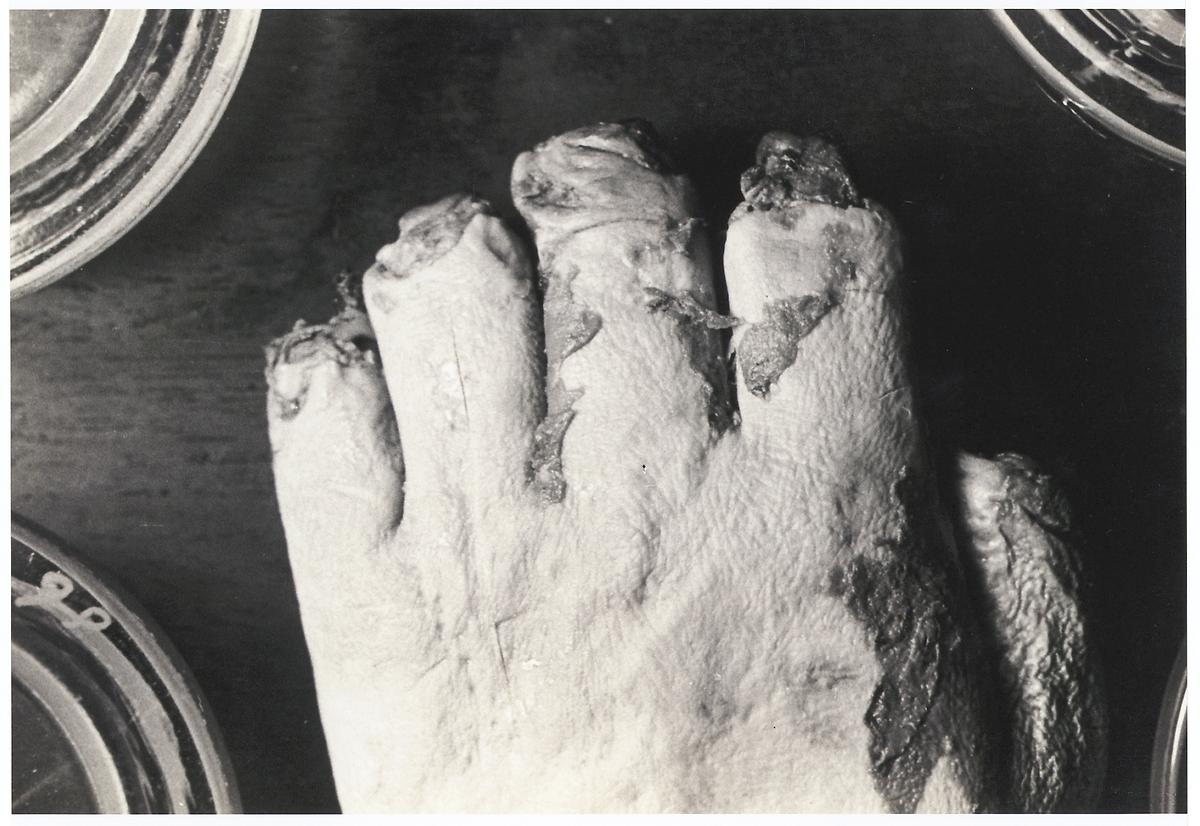

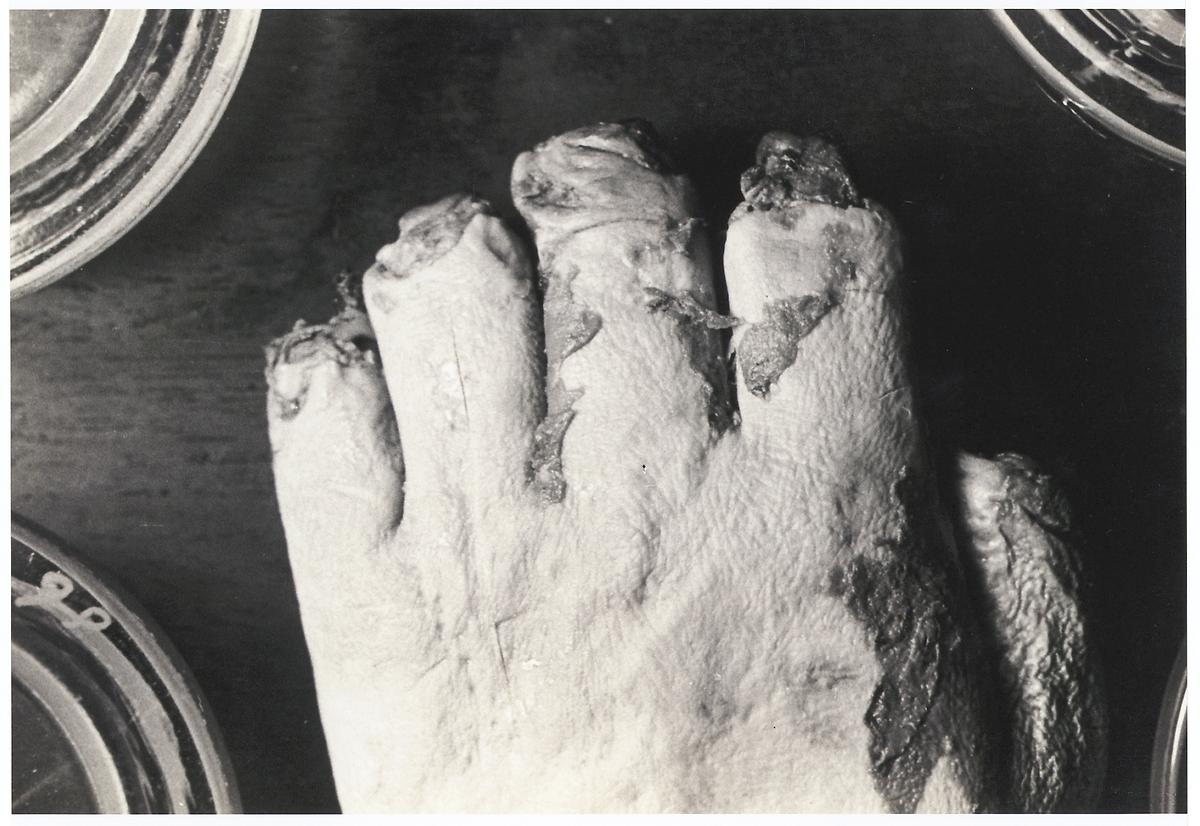

The tips of the

fingers of the victims were cut off

to prevent fingerprint

identification, 1935.

The tips of the

fingers of the victims were cut off

to prevent fingerprint

identification. The skill with which

the fingers

were mutilated led

police to hypothesize that the

murderer had anatomical training and

knew how to use a scalpel.

(University of

Glasgow)

Dr.

John Glaister, Jr. (left)

and two other men, at

Moffat during the Ruxton

murder investigation,

about 1935

Portions of the victims'

bodies were bundled

together in bags under

the bridge at Moffat,

England, near the

Scottish border. Other

parts, including their

heads, were strewn about

the banks of the creek

and adjacent areas.

Their task was made

easier by the fact that,

while Dr. Ruxton had

worked hard to render

the bodies

unidentifiable, he had

not been thorough and

made many mistakes.

(University of Glasgow)

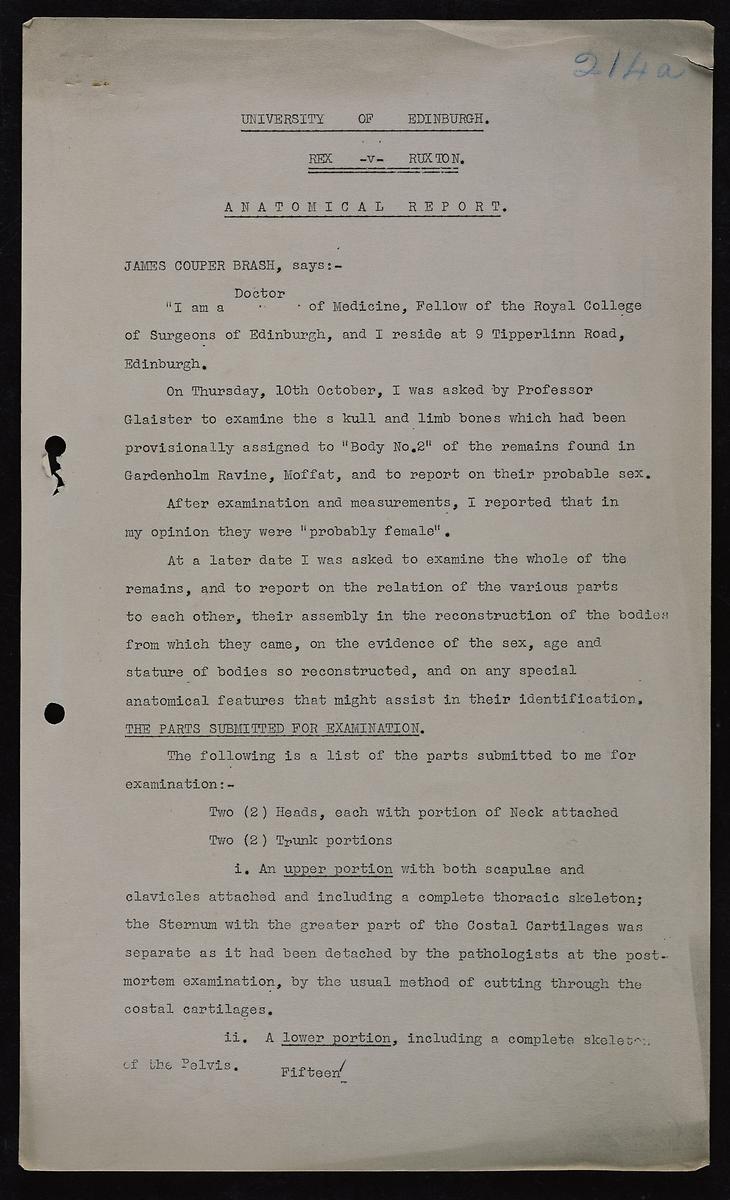

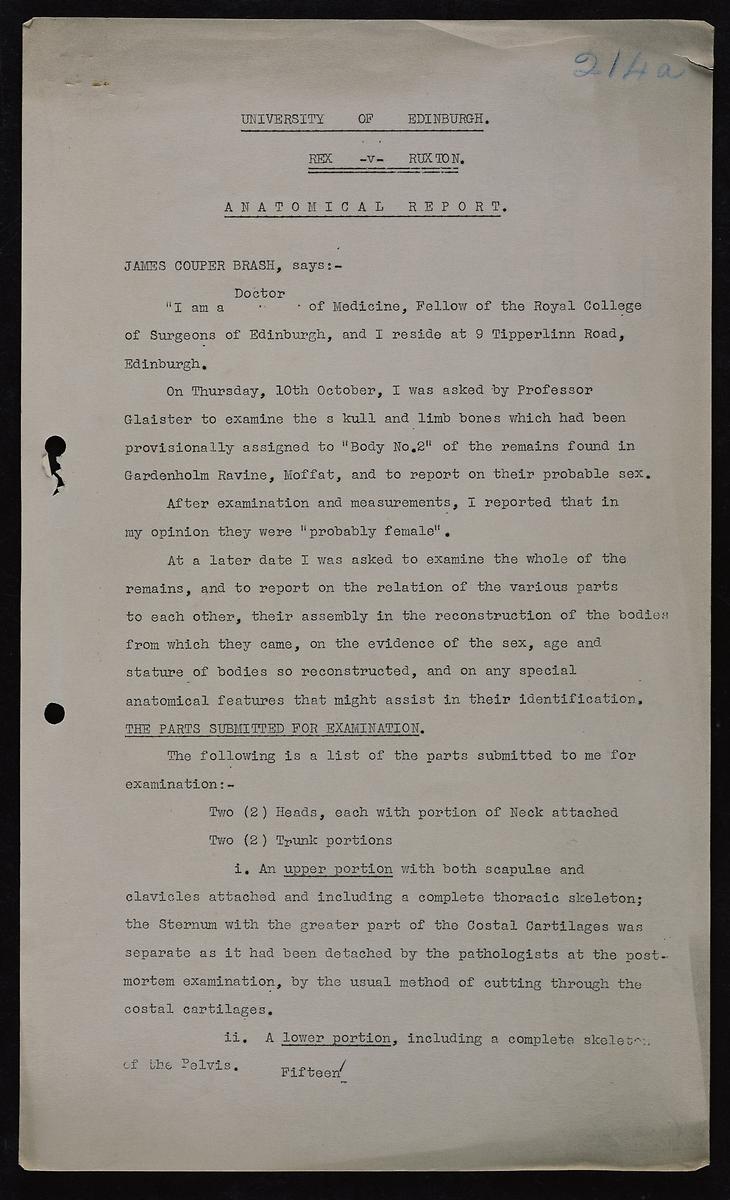

Rex v. Ruxton,

Anatomical Report, University of

Edinburgh, 1935.

The Anatomical

Report submitted in the case of

Rex v. Ruxton by James Cooper

Brash of the University of

Edinburgh. Investigators had to

find, and then sort and

reassemble, the remains of the

victims; investigate and

reconstruct the crime; and

marshal the circumstantial and

forensic evidence that could be

introduced as evidence at a

trial. (University of

Glasgow)

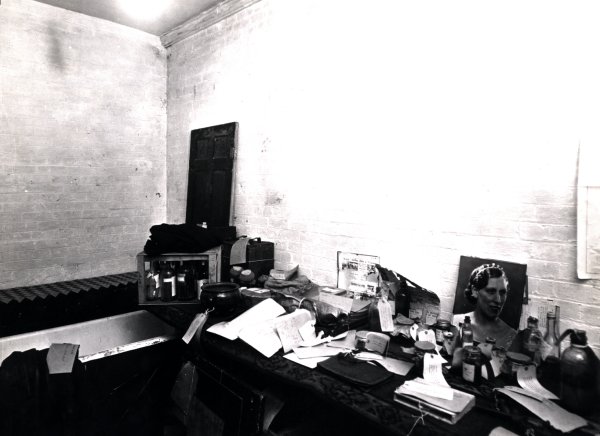

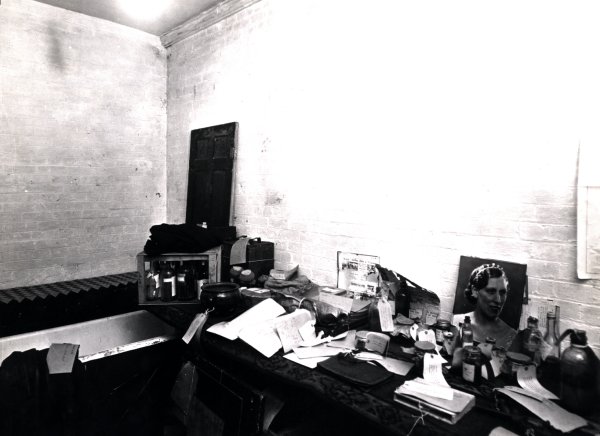

Examination of

productions for use in

the trial.

Evidence/productions

are collected for the

trial of the accused, Dr

Buck Ruxton. This

photograph shows

numerous labelled

productions which

underwent stringent

laboratory tests at the

University of Glasgow,

and were then submitted

in court as formal

pieces of evidence; they

include a bath and a

photographic portrait of Ruxton's wife.

(Image

courtesy of Glasgow

University Archive

Services)

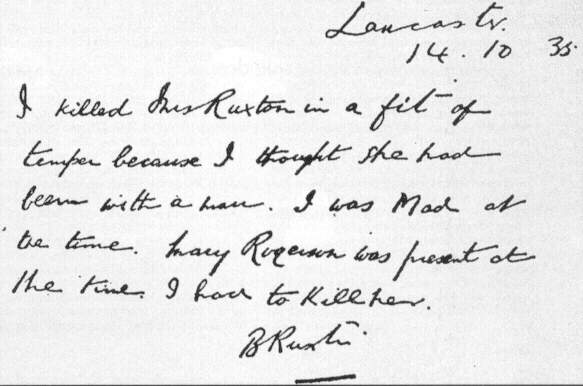

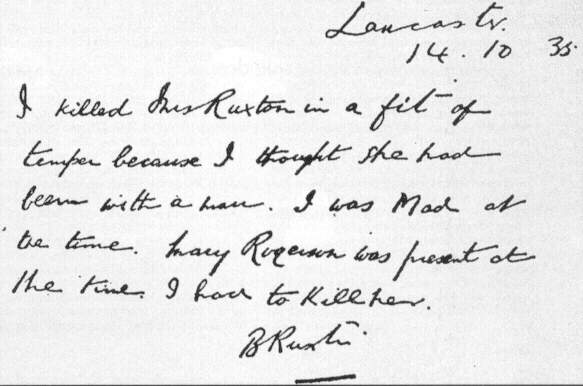

Manuscript confession.

1st March 1936: A group

of women having

breakfast on the

pavement outside the

courts in Manchester

before the start

of the trial of Dr. Buck Ruxton. (Fox Photos/Getty

Images)

Police hold back a crowd

of sightseers outside

Strangeways gaol in

Manchester

before the

execution of Dr Buck Ruxton.

(Fox Photos/Getty

Images)

|