United States Court of Appeals for the eighth circuit

No. 97-1576WM

Roy Ramsey,

Appellant,

v.

Michael Bowersox,

Superintendent,

Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Western District of Missouri.

Submitted: April 16,

1998

Filed: June

10, 1998

Before FAGG, JOHN R. GIBSON, and HANSEN, Circuit Judges.

FAGG, Circuit Judge.

Roy Ramsey, a Missouri death row inmate, appeals the district court's denial of his petition for a writ of habeas corpus. See 28 U.S.C. § 2254. We affirm.

On November 21, 1988, Ramsey and his brother, Billy, went to the home of an elderly couple, Garnett and Betty Ledford, to rob them. Billy's girlfriend drove the brothers there in her car. Ramsey had a gun, but Billy did not. Garnett answered the door, and Ramsey used the gun to force his way inside.

The brothers took the Ledfords upstairs to a bedroom. After Betty opened the Ledfords' safe, the brothers tied her in a chair. Billy went downstairs with some of the loot, including money, guns, a videocassette recorder, and foreign coins, and Ramsey killed the Ledfords by shooting each of them at close range in the head.

Several days later, the brothers were caught. Billy entered a plea agreement and testified against Ramsey in exchange for a twenty-five-year sentence. A Missouri jury convicted Ramsey of first-degree murder and sentenced him to death. The Missouri Supreme Court affirmed Ramsey's conviction and sentence on direct appeal. See State v. Ramsey , 864 S.W.2d 320 (Mo. 1993), cert. denied , 511 U.S. 1078 (1994).

Ramsey filed this federal habeas petition in December 1995. A year later, the district court denied Ramsey's petition. Seeking permission to appeal twenty-five issues, Ramsey asked us "for a certificate of appealability pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2253(c) and Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 22(b)." We remanded Ramsey's request to the district court for compliance with the statute and rule cited by Ramsey.

The district court granted a certificate of appealability on eleven issues and denied a certificate on fourteen others. Ramsey then sought an expanded certificate of appealability or certificate of probable cause from us. We denied Ramsey's request and thus limited the issues to only those that satisfied the standard for granting either certificate--the same eleven identified by the district court. We turn initially to the eleven issues certified for appeal.

Ramsey first asserts he was denied effective assistance of counsel and due process because his trial attorney had a conflict of interest. During the hearing on Ramsey's motion for a new trial, the prosecutor brought the court's attention to a newspaper article that spoke of letters written to Ramsey from Billy, whose judgment in accordance with his plea agreement could still be set aside. In the letters, Billy apologized for giving false testimony at Ramsey's trial.

The trial court asked Ramsey's attorney to produce the letters, and the attorney refused, citing a conflict of interest. Ramsey asserts a conflict existed at the posttrial hearing with respect to the letters' production because his attorney was at risk of being found to have provided ineffective assistance during the trial in failing to use the letters. Ramsey's counsel, a Missouri public defender from the district 48 office (Trial Trans. at 1852) sought to withdraw, but the court denied the motion.

Although the court doubted a conflict existed, the court obtained a different Missouri public defender from the district 16 office (Trial Trans. at 1852) to advise Ramsey on the limited issue of whether to produce the letters at the hearing on the motion for a new trial. Ramsey decided not to produce the letters. Ramsey contends his trial attorney's posttrial conflict carries over to all the Missouri public defender's offices, and thus the court should have appointed an attorney in private practice to advise him.

To prevail on his claim, Ramsey must show both an actual conflict of interest and an adverse effect on his attorney's performance. See Nave v. Delo , 62 F.3d 1024, 1034 (8th Cir. 1995), cert. denied , 517 U.S. 1214 (1996). Even if Ramsey's trial attorney had a conflict posttrial about production of the letters, it cannot be imputed to the attorney from a different Missouri public defender's office solely by reason of the statutorily created relationship between the offices. See id. at 1034-35.

Besides, Ramsey has not shown any adverse effect from the presumed advice not to produce the letters at the new trial hearing. Ramsey's ineffective assistance claim also fails because, as the Missouri Supreme Court found, his trial attorney's failure to introduce the letters as evidence at trial was not deficient performance, but sound trial strategy. See Ramsey , 864 S.W.2d at 339. Indeed, at the new trial hearing, Billy testified his trial testimony was truthful and the letters were fabricated.

Second, Ramsey attacks the Missouri Supreme Court's proportionality review of his death sentence on direct appeal under Mo. Rev. Stat. § 565.035. Contrary to Ramsey's assertions, Missouri's proportionality review does not violate the Eighth Amendment, due process, or equal protection of the laws. See Sweet v. Delo , 125 F.3d 1144, 1159 (8th Cir. 1997), cert. denied , 118 S. Ct. 1197 (1998).

The Missouri Supreme Court concluded Ramsey's "sentence is not disproportionate," Ramsey , 864 S.W.2d at 327, and we see no basis for looking behind that conclusion, see Sweet , 125 F.3d at 1159. Third, Ramsey contends his death sentence is based on an invalid aggravating circumstance: that the homicide was "outrageously or wantonly vile, horrible or inhuman in that it involved torture or depravity of mind."

According to Ramsey, this aggravating circumstance is vague or overbroad because it does not define "torture or depravity of mind." "A finding of torture is sufficient to properly narrow the class of persons eligible for the death penalty." LaRette v. Delo , 44 F.3d 681, 686 (8th Cir. 1995). As for depravity of mind, the Missouri Supreme Court has judicially defined and limited the term. See Ramsey , 864 S.W.2d at 328.

In Ramsey's case, the court gave the term a limiting construction by instructing the jury it could find depravity if it found Ramsey bound Betty or planned to kill more than one person, and had a callous disregard for human life. The limiting construction gave adequate guidance to the sentencer. See Battle v. Delo , 19 F.3d 1547, 1562 (8th Cir. 1994). Even if the instruction were unconstitutionally vague, the jury's penalty phase verdict was reliable because the jury found several other unchallenged aggravating circumstances that support Ramsey's death sentence. See Sloan v. Delo , 54 F.3d 1371, 1385-86 (8th Cir. 1995) (in nonweighing state like Missouri, jury's finding of invalid aggravating factor does not invalidate death verdict when jury finds at least one valid aggravating factor).

Fourth, Ramsey contends his right to confront and cross-examine witnesses against him was violated when the trial court admitted parts of a videotaped statement by Billy about Ramsey's role in the murders. Police made the tape when they brought Billy, a suspect in the murders, into the police station for questioning early in the investigation, before Billy made a plea bargain. Billy initially denied any knowledge of the robbery, then said someone other than Ramsey was his accomplice.

After police confronted Billy with the statements of his mother, aunt, and girlfriend saying Ramsey and Billy committed the robbery and Ramsey had a gun, Billy gave the videotaped statement implicating his brother. At the prosecutor's behest, the trial court admitted parts of the tape in rebuttal after defense counsel suggested on cross-examination that Billy fabricated his trial testimony to save his own neck.

Defense counsel had brought out that Billy's testimony was the product of a plea bargain and there were inconsistencies between Billy's trial testimony and earlier statements made in his deposition and at the time of his arrest. Although the court admitted parts of the tape, the court instructed the jury it should not consider the tape as substantive evidence.

We see no violation of Ramsey's right to confront witnesses against him. "[T]he Confrontation Clause is not violated by admitting a declarant's out-of-court statements, as long as the declarant is testifying as a witness and subject to full and effective cross-examination." California v. Green , 399 U.S. 149, 158 (1970); see McDonnell v. United States , 472 F.2d 1153, 1155- 56 (8th Cir. 1973).

In Ramsey's case, Billy testified as a witness at trial, and Ramsey does not identify anything that prevented him from recalling Billy and questioning him about the tape. Ramsey's inability to cross-examine Billy earlier when he gave the statement at the police station does not violate the Confrontation Clause. See Green , 399 U.S. at 159 (inability to cross-examine witness at time of out-of-court statement is insignificant if defendant can cross-examine witness at trial).

Ramsey misplaces reliance on Tome v. United States , 513 U.S. 150, 156-60 (1995) (witness's earlier consistent out-of-court statement introduced to rebut charge of recent fabrication or improper influence or motive is inadmissible under Federal Rule of Evidence 801(d)(1)(B) when made before alleged fabrication, influence, or motive came into being). The Missouri Supreme Court decided the videotaped statements were admissible under state evidentiary law consistent with Tome , see Ramsey , 864 S.W.2d at 329, and we cannot disturb that decision. See Cornell v. Iowa , 628 F.2d 1044, 1048 n.3 (8th Cir. 1980).

Fifth, Ramsey asserts the prosecutor made improper arguments during the trial's guilt phase. Ramsey can receive no federal habeas relief based on a prosecutor's improper statements unless the prosecutor's misconduct infected the entire proceeding and rendered it fundamentally unfair in violation of due process. See Newlon v. Armontrout , 885 F.2d 1328, 1336 (8th Cir. 1989).

Contrary to Ramsey's view, the prosecutor did not indirectly comment on Ramsey's failure to testify. The challenged comments do not show the prosecutor intended to call attention to Ramsey's failure to testify, and we do not think the jury would naturally and necessarily understand the comments as highlighting Ramsey's failure to take the stand. See United States v. Moore , 129 F.3d 989, 993 (8th Cir. 1997), cert. denied , 118 S. Ct. 1402 (1998).

The evidence showed that when police arrested Ramsey at his mother's home on a charge unrelated to the murder, they found a foreign coin in his pocket. Ramsey tried to persuade the police to give the coin to his mother, but the police refused. During closing argument in the guilt phase, Ramsey's attorney said there was no evidence the coin found in Ramsey's pocket belonged to the Ledfords, even though there was evidence foreign coins were taken in the robbery.

In response, the prosecutor argued, "Roy Ramsey alone . . . knows where the coin came from. . . . Who, by his actions, let you know not only that this coin was part of the homicide but that he knew that by being in possession of this, he was caught. Roy Ramsey." (Trial Trans. at 1521-22.) Rather than commenting on Ramsey's failure to testify, the prosecutor pointed out that Ramsey's actions showed his consciousness of guilt because he knew the coin belonged to the Ledfords and could possibly tie him to the murders. Nor did the prosecutor comment on Ramsey's failure to testify in saying, "The uncontradicted evidence is that Roy Ramsey and Billy knew, with certainty, that Garnett Ledford knew Billy." (Trial Trans. at 1462.) Comments that the state's evidence is uncontradicted simply refer to the clarity and strength of the state's evidence. See Moore , 129 F.3d at 993.

We also reject Ramsey's assertion that the prosecutor's reference to Ramsey as "Rambo" was improper. The reference was permissible argument because it was based on trial testimony. See Pickens v. Lockhart , 4 F.3d 1446, 1453-54 (8th Cir. 1993). When asked who got the foreign coins stolen in the robbery, Billy responded, "Rambo, Roy." The prosecutor then said, "You just said something. What is Mr. Ramsey's nickname?" Billy responded, "Rambo." (Trial Trans. at 989.) The prosecutor then shifted to another line of questioning. The prosecutor cannot be faulted for capitalizing on this unsolicited evidence in his closing argument.

Sixth, Ramsey asserts parts of the prosecutor's penalty-phase closing argument were improper. Based on evidence that criminals become less dangerous as they age, Ramsey argued lack of future dangerousness as a mitigating factor in sentencing. In response, the prosecutor argued, "Roy Ramsey, Rambo, is not burning out. . . . We have no reason to believe anything else. Roy Ramsey, while in the most secure prison in the state, sodomized a member of our society. And that's something I am having trouble with. We can't protect people in our society from Roy Ramsey." (Trial Trans. at 1755-56.) Ramsey contends this argument improperly contorted a mitigating factor into an aggravating factor, injected evidence outside the record, and stated the prosecutor's personal opinion. We see no constitutional error.

The state had presented evidence that Ramsey committed sodomy in October 1976 "while awaiting trial" for robbing a man in August. See Ramsey , 864 S.W.2d at 333. That the sodomy happened in prison is a reasonable inference from the evidence. See id. Thus, the prosecutor could properly argue Ramsey could be dangerous in prison. See United States v. Atcheson , 94 F.3d 1237, 1244 (9th Cir. 1996) (no misconduct where prosecutor argued reasonable inferences based on record), cert. denied , 117 S. Ct. 1096 (1997). Even if the prosecutor's reference to his own trouble with Ramsey's act of sodomy was improper, there is not a reasonable probability the isolated remark affected the outcome of the penalty phase. See Newlon , 885 F.2d at 1337-38.

Seventh, Ramsey contends his rights to due process and a fair and impartial jury were violated when the trial court refused his proposed voir dire questions directed at the prospective jurors' ability to be impartial in sentencing Ramsey. "Voir dire plays a critical role in assuring criminal defendants that their Sixth Amendment right to an impartial jury will be honored. Without an adequate voir dire the trial judge cannot fulfill [the] responsibility to remove prospective jurors who may be biased and defense counsel cannot intelligently exercise peremptory challenges." United States v. Spaar , 748 F.2d 1249, 1253 (8th Cir. 1984).

Nevertheless, trial judges have broad discretion to decide how to conduct voir dire, and they are not required to ask a question in any particular form simply because a party requests it. See id. A trial judge's refusal to ask certain voir dire questions is proper when the judge's overall examination, coupled with the charge to the jury, adequately protects the defendant from prejudice. See id.

Ramsey proposed the following voir dire questions:

Could each of you consider the death penalty in this case with the understanding that under Missouri law you are never required to impose it? If Roy Ramsey is convicted of first- degree murder, are there any of you who feel he should get the death penalty regardless of any mitigation circumstances? If you are convinced beyond a reasonable doubt, that Roy Ramsey is guilty of first-degree murder, would the defense have to convince you that he should not get the death penalty? Would your views on the death penalty prevent or substantially impair your ability to follow the following instruction: You are not compelled to fix death as the punishment, even if you do not find the existence of one or more mitigating circumstances, sufficient to outweigh the aggravating circumstances or circumstances which you find to exist. You must consider all of the circumstances in deciding whether to assess and declare the punishment at death. Whether that is to be your final decision rests with you. If you find one or all of the aggravating circumstances exist beyond a reasonable doubt, could you still consider life without parole as a possible punishment? If you found aggravating circumstances exist beyond a reasonable doubt and that they warrant the death penalty, could you still consider life without parole as a possible punishment? If you find aggravating circumstances beyond a reasonable doubt and find that the mitigating circumstances do not outweigh the aggravating circumstances, would you still consider life without probation or parole as a possible punishment?

Rather than posing these questions, the trial court told the jurors, "I'm going to ask you some questions [about] imposition of the death penalty. These questions are asked of you in the abstract, understanding that no evidence has been presented. . . . If you were selected as a juror in this case, you must be able to vote for both of the punishments authorized by law. My question is would you be capable of voting for a sentence of death? Would you be capable of voting for a sentence of life without parole?" (Trial Trans. at 578-80.) To help the attorneys exercise their peremptory challenges, the court also asked, "If you were chosen as a juror, would you have a tendency to favor either the death penalty, the life imprisonment penalty, or neither?" (Trial Trans. at 580.)

The trial court's queries were more direct and succinct than Ramsey's proposed questions, and addressed the crucial disqualification issue of whether the prospective jurors would automatically vote for or against the death penalty in every case, see Morgan v. Illinois , 504 U.S. 719, 728-29 , 732 (1992). Because the trial court's questioning reasonably assured Ramsey of a chance to detect a potential juror's prejudice about the death penalty, see Spaar , 748 F.2d at 1253, Ramsey was not denied his rights to due process and a fair trial.

Eighth, Ramsey asserts the jury instructions improperly limited the jury's consideration of mitigating circumstances. Ramsey complains that the instructions required the jury to decide whether the aggravating circumstances warranted imposition of death before the jury could consider any mitigating circumstances. As Ramsey sees it, the instructions improperly placed the burden on him to prove the mitigators outweighed the aggravators before he could receive the benefit of the mitigating circumstances.

In Bolder v. Armontrout , 921 F.2d 1359, 1367 (8th Cir. 1990), we rejected the same attack on Missouri sentencing instructions like those given in Ramsey's case. The Supreme Court recently approved similar capital sentencing instructions in Buchanan v. Angelone , 118 S. Ct. 757, 761-62 (1998). The instructions in Ramsey's case were proper because after the jury found the existence of an aggravating circumstance, the jury was not required to impose the death penalty even if the jury found no mitigating evidence. See Bolder , 921 F.2d at 1367; Buchanan , 118 S. Ct. at 761-62.

Ninth, Ramsey asserts Missouri's reasonable doubt instructions allowed the jury to convict him based on a lower burden of proof than the Constitution requires. Ramsey complains that the instructions defined proof "beyond a reasonable doubt" as that leaving the jury "firmly convinced" of Ramsey's guilt. We have already decided we would have to go beyond existing Supreme Court precedent to find constitutional infirmity in Missouri's instruction charging the jury to be "firmly convinced" before convicting a defendant. See Murray v. Delo , 34 F.3d 1367, 1382 (8th Cir. 1994).

Thus, we have held this challenge to Missouri's reasonable doubt instruction is barred by Teague v. Lane , 489 U.S. 288 (1989). See Murray , 34 F.3d at 1382; Reese v. Delo , 94 F.3d 1177, 1186 (8th Cir. 1996), cert. denied , 117 S. Ct. 2421 (1997). Also, Justice Ginsburg has indicated her approval of an instruction proposed by the Federal Judicial Center that defines proof beyond a reasonable doubt as proof leaving a juror firmly convinced. See Victor v. Nebraska , 511 U.S. 1, 26-27 (1994) (Ginsburg, J., concurring).

Tenth, Ramsey contends the trial court's denial of his challenges for cause to venirepersons who leaned toward the death penalty violated his rights to an impartial jury, due process, and equal protection in violation of the Sixth, Fifth, and Fourteenth Amendments. When the court denied Ramsey's motion challenging prospective jurors Atwood and Dillon for cause, Ramsey used peremptory challenges to dismiss them. Because Ramsey has not shown the seated jury was partial, his Sixth Amendment claim fails. See Cox v. Norris , 133 F.3d 565, 572 (8th Cir. 1997); Sloan , 54 F.3d at 1387 n.16. Loss of a peremptory challenge does not violate the constitutional right to a fair jury. See Cox , 133 F.3d at 572.

As for his due process claim, Ramsey must show he did not receive some right to peremptory challenges provided for by Missouri law. See Sloan , 54 F.3d at 1387. At the time of Ramsey's trial, Missouri law provided that "criminal defendants are entitled to a `full panel of qualified jurors before being required to make peremptory challenges' and [] failure to sustain a meritorious challenge for cause is prejudicial error." Id. (quoting State v. Wacaser , 794 S.W.2d 190, 193 (Mo. 1990)).

The trial court decided the views of Atwood and Dillon would not prevent or substantially impair their performance as jurors, and thus overruled Ramsey's challenges for cause. See Ramsey , 864 S.W.2d at 336. On habeas review, our role is limited to deciding whether the record fairly supports the state court's decision that Atwood and Dillon could be impartial. See Sloan , 54 F.3d at 1387. We see no manifest error. See id. Atwood and Dillon both said they were capable of voting for either the death sentence or life imprisonment without parole before stating their tendency to lean towards the death penalty. (Trial Trans. at 582- 83, 635.)

Given the trial court's introductory statements about aggravating and mitigating factors and the necessity of the prospective jurors' ability to follow the instructions (Trial Trans. at 578-80, 630-31), the unequivocal responses of Atwood and Dillon indicating they could vote for either sentence made clear they would not impose either sentence automatically and thus were qualified to sit as impartial jurors. See Morgan , 504 U.S. at 728 -29. As a result, Ramsey received a full panel of qualified jurors before exercising peremptory challenges, and the trial court properly denied Ramsey's challenges for cause. See Sloan , 54 F.3d at 1387.

Ramsey complains that the trial court did not allow him to ask Atwood and Dillon whether their views on capital punishment would prevent or substantially impair the performance of their duties as jurors in accordance with their instructions and their oath. (Trial Trans. at 595); see Morgan , 504 U.S. at 728 . In context, the statements of Atwood and Dillon that they could impose either sentence fairly supports the state court's decision that their views would not substantially impair their performance as jurors. See Ramsey , 864 S.W.2d at 336. As we said in our discussion about Ramsey's proposed voir dire questions, the questions asked by the trial court were sufficient to identify unqualified jurors. See Morgan , 504 U.S. at 728 -36. No further questions were constitutionally required. We conclude the trial court did not violate Ramsey's right to due process.

With respect to equal protection, Ramsey claims the court used two separate standards for juror qualification, one to retain jurors who favored the death penalty, and another to exclude jurors who questioned the death penalty's propriety. Contrary to Ramsey's claim, the record of voir dire shows the court was evenhanded.

The court asked more questions when a potential juror stated an inability to impose either life imprisonment or death, but not when a potential juror expressed a tendency to lean toward either sentence. The information about a prospective juror's tendency helped both the prosecution and the defense decide how to exercise peremptory challenges, and Ramsey used some of his to remove Atwood and Dillon.

In his eleventh claim, Ramsey asserts jury instructions five and seven violate due process because the instructions confuse the elements of first-degree murder and improperly shift the burden of proving deliberation to Ramsey. The instructions stated that if the jury found Ramsey or his brother had killed the Ledfords by shooting, the shooter knew his conduct was practically certain to cause death, and the shooter had deliberated for any length of time, first-degree murder had occurred, and if the jury found that "with the purpose of promoting or furthering the death of [the Ledfords], [Roy Ramsey] acted alone or together with or aided or encouraged Billy Ramsey in causing the death of [the Ledfords] and [Roy Ramsey] did so after deliberation, . . . then [the jury would] find [Roy Ramsey] guilty . . . of murder in the first degree."

Contrary to Ramsey's assertion, the instruction plainly required the jury to find beyond a reasonable doubt that Ramsey himself had deliberated, as Missouri law requires, see State v. Ferguson , 887 S.W.2d 585, 587 (Mo. 1994). The instruction did not violate due process. See Kilgore v. Bowersox , 124 F.3d 985, 991 (8th Cir. 1997); Thompson v. Missouri Bd. of Probation & Parole , 39 F.3d 186, 190 (8th Cir. 1994); see also Baker v. Leapley , 965 F.2d 657, 659 (8th Cir. 1992) (per curiam) (to warrant federal habeas relief for state prisoner, instructional error must constitute a fundamental defect that results in a complete miscarriage of justice or renders the defendant's entire trial unfair).

Last, Ramsey contends the district court should have given him permission to raise fourteen more issues on appeal. In Ramsey's view, the district court committed error in granting him a certificate of appealability limited to eleven issues under 28 U.S.C. § 2253 as amended by the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act.

Although he initially requested a certificate of appealability and we remanded the question of the certificate's issuance to the district court, Ramsey now asserts the district court should have given him an unlimited certificate of probable cause under the pre-Act version of § 2253. Ramsey filed his habeas petition in December 1995 before the Act's April 1996 effective date, and he asserts the Act does not govern habeas petitions filed before then. See Lindh v. Murphy , 117 S. Ct. 2059 (1997).

Section 2253 requires a state prisoner to obtain authorization from a district or circuit judge before appealing from the denial of a federal habeas petition. Before the Act, § 2253 required a state prisoner to obtain a certificate of probable cause. See 28 U.S.C. § 2253 (1994). The Act amended § 2253 to require a state prisoner to obtain a certificate of appealability. See 28 U.S.C.A. § 2253(c) (West Supp. 1998). The same substantive standard governs issuance of the pre-Act certificate of probable cause and the post-Act certificate of appealability. See Roberts v. Bowersox , 137 F.3d 1062, 1068 (8th Cir. 1998); Tiedeman v. Benson , 122 F.3d 518, 521 (8th Cir. 1997).

Both certificates issue only if the applicant makes a substantial showing of the denial of a constitutional right. See Roberts , 137 F.3d at 1068; Cannon v. Johnson , 134 F.3d 683, 685 (5th Cir. 1998); see also Barefoot v. Estelle , 463 U.S. 880, 893 (1983). The post-Act certificate of appealability requires a judge to specify which issues satisfy this standard, see 28 U.S.C. § 2253(c)(3), and appellate review of the habeas denial is limited to the specified issues, see Lackey v. Johnson , 116 F.3d 149, 151 (5th Cir. 1997).

The pre-Act certificate of probable cause did not require specification and placed the entire case before the court of appeals, see Roberts , 137 F.3d at 1068, but the court of appeals could confine the issues on appeal to those satisfying the substantial showing standard, see Garrison v. Patterson , 391 U.S. 464, 466 (1968) (per curiam) (court of appeals may consider the certificate of probable cause and merits questions together; full briefing and oral argument is not required in every case in which a certificate of probable cause is granted). Indeed, courts of appeals have been exercising this discretion for years. See Vicaretti v. Henderson , 645 F.2d 100, 101 (2d Cir. 1980) (recognizing practice by several circuits of issuing limited certificates of probable cause); Camillo v. Wyrick , 640 F.2d 931, 934 (8th Cir. 1981) (Eighth Circuit confined issues in order granting a certificate of probable cause).

As Ramsey acknowledges, we have already held the Act's amended version of § 2253 applies to habeas petitioners like him, who filed their habeas petitions before the Act's effective date but had not yet appealed the denial of their habeas petition. See Tiedeman , 122 F.3d at 520-21. Citing contrary cases from other circuits, Ramsey argues Tiedeman was wrongly decided. One panel of this court is bound by the decisions of other panels, however. See United States v. Rodamaker , 56 F.3d 898, 903 (8th Cir. 1995).

Even if the new certificate of appealability requirement does not apply to Ramsey's pre-Act habeas petition, Ramsey would be no better off. The district court would have granted Ramsey a certificate of probable cause, and although Ramsey would have been free to choose which claims to assert on appeal, we would have narrowed the issues for full briefing on the merits to the same eleven selected by the district court.

In our December 22, 1997 order denying Ramsey's application to us for an expanded certificate of appealability or certificate of probable cause, we decided Ramsey had not made a substantial showing of the denial of a constitutional right with respect to the fourteen rejected issues.

Ramsey does not challenge our decision to limit the issues in his appellate brief, explain why the fourteen rejected issues meet the substantial showing standard, or point out how the district court or this court made a mistake in concluding the fourteen issues do not warrant full briefing and oral argument on appeal. See Kerr v. Federal Emergency Management Agency , 113 F.3d 884, 886 n.3 (8th Cir. 1997) (argument waived when not supported by specific law or facts from record).

In sum, Ramsey has not shown the rejected issues merit appeal by carrying his burden to make a substantial showing of the denial of a constitutional right on those issues. See Barefoot , 463 U.S. at 893 . Having considered all of Ramsey's arguments, we affirm the district court's denial of Ramsey's petition for a writ of habeas corpus.

JOHN R. GIBSON, Circuit Judge, concurs in the result and concurs in the judgment.

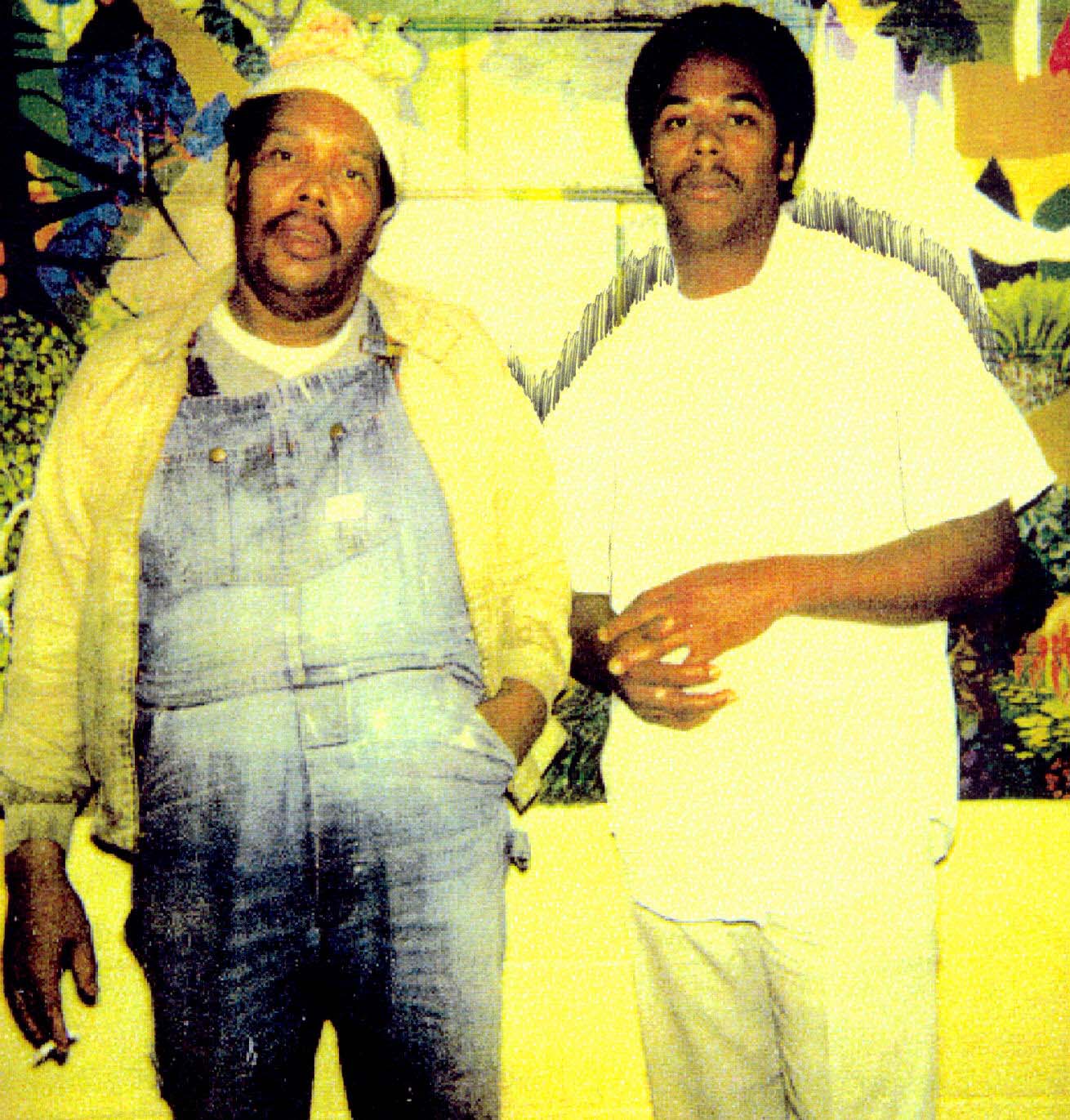

Roy Ramsey (right) with his father (left).