A guardís belated

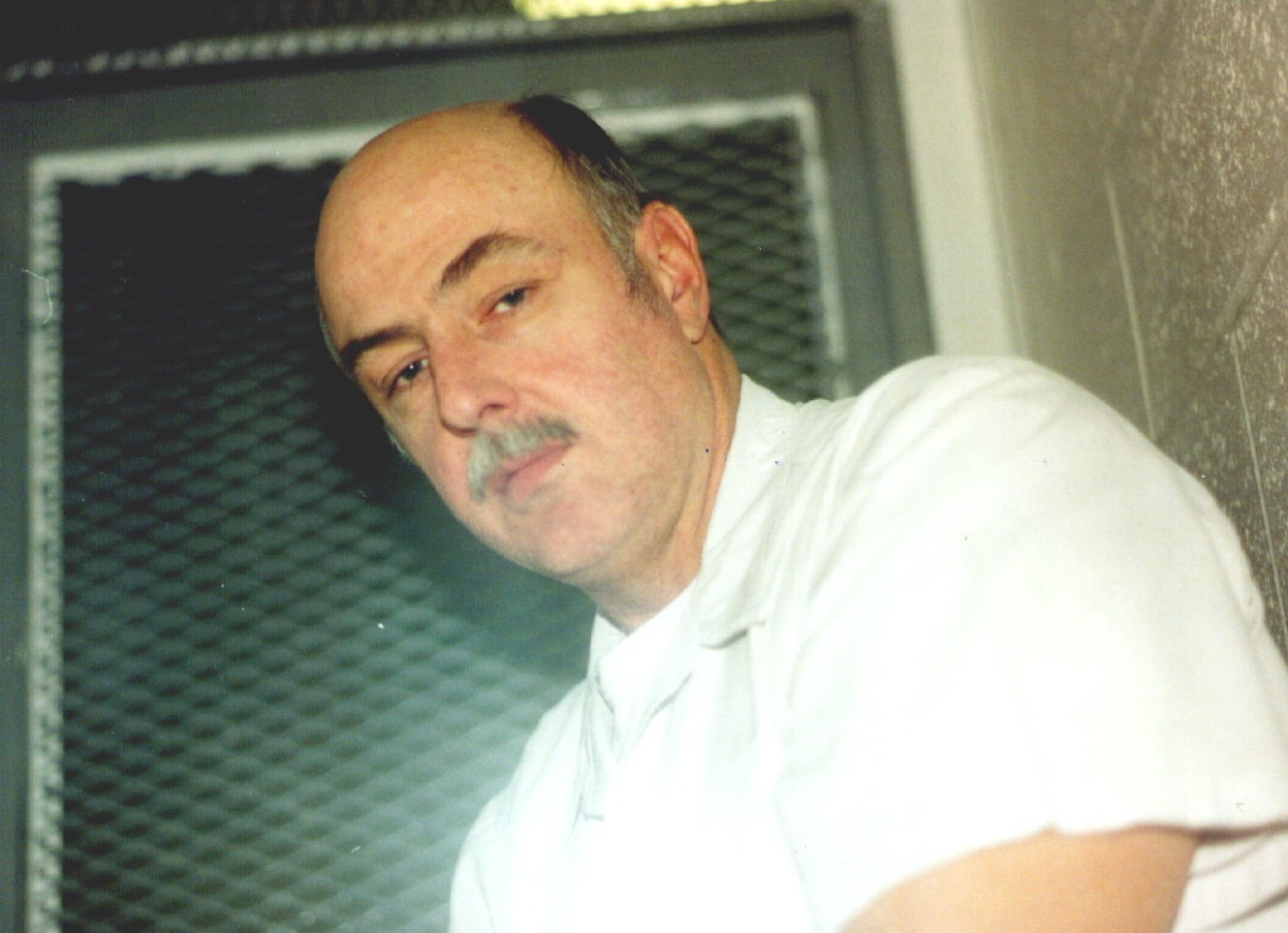

"recollection" led to the execution of Roy Michael Roberts

Roy Michael Roberts, a 46-year-old

laborer from south St. Louis, was executed at Missouriís Potosi

Correctional Center at 12:07 a.m. on March 10, 1999, for the murder

of a prison guard 16 years earlier ó a crime Roberts insisted he did

not commit. His last words were, "Youíre killing an innocent man."

Perverse juxtaposition

In the weeks

preceding Robertsís execution, Missouri Governor Mel Carnahan had

been the focus of an intense controversy because, in response to a

personal plea from Pope John Paul II, he had granted clemency to

Darrell Mease, a confessed triple murderer. Mease had been scheduled

to die by lethal injection during a January papal visit to St.

Louis.

The Reverend Larry Rice, founder of the New

Life Evangelic Center in St. Louis and one of Missouriís leading

death penalty abolitionists, contends the Mease clemency thrust the

politically ambitious Carnahan into a defensive posture that

probably sealed Roy Robertsís fate even before his clemency petition

landed on the governorís desk. (After the execution, Rice suggested

a campaign slogan for Carnahan, who had recently announced his

candidacy for the U.S. Senate in 2000: "Iíll kill for this job.")

The Mease-Roberts life-death juxtaposition was perverse: Due to the

coincidental timing of John Paulís Missouri trip, a killer whose

multiple victims included a paraplegic, is alive. Yet a man who had

unwaveringly professed innocence, who had passed a lie-detector test,

who had earned two college degrees in prison, who had been condemned

on the testimony of dubious witnesses ó prison guards who were

contradicted by a fellow guard and a parade of defense witnesses ó

is dead.

The crime

The crime for

which Roberts died was the 1983 murder of a guard at a medium

security prison in Moberly, Missouri, where Roberts was serving the

final months of a sentence for a 1978 armed robbery. The victim, 62-year-old

Thomas G. Jackson, Jr, was stabbed to death during a melee involving

drunken prisoners.

During the initial

investigation, which included searches of cells for evidence and

interviews with every guard and prisoner in any proximity to the

killing, no evidence was found that in any way appeared to implicate

Roberts. Not a single witness, guard or prisoner, ascribed any role

whatsoever to Roberts.

Blood-stained clothing and

shanks were seized from two other prisoners, Rodney Carr and Robert

Driscoll, who wound up as Robertsís co-defendants, but Roberts was

not identified as a participant until two weeks after the fact. The

belated allegation against Roberts came from Denver Hawley, a guard

Roberts claimed bore him grudge stemming from his refusal to work in

the prison laundry. Hawley denied any such grudge, but somehow never

could explain why, in two previous reports on the riot, he had

neglected to mention Roberts.

The trial

At trial, Hawleyís testimony was corroborated by

two other guards, both of whom also initially had not implicated

Roberts. However, a fourth guard testified that Roberts was at the

other end of the tier when Jackson was murdered; thus, he could not

have been guilty. A prisoner who corroborated Hawley at trial

subsequently recanted, saying he had been coerced by prison

officials to falsely implicate Roberts.

Although Robertsís co-defendants did not testify

at his trial (they were awaiting trial themselves at the time) both

later said Roberts was not involved. One co-defendant, Rodney Carr,

the only one, ironically, against whom prosecutors had a solid case,

received only a life sentence. The other, Robert Driscoll, was

sentenced to death, but won a new trial in a federal habeas corpus

proceeding after showing that Dr. Kwei Lee Su, chief forensic

serologist for the Missouri State Police, withheld evidence that

blood on a shank found in his cell could not have been Jacksonís.

Driscoll was again convicted and again sentenced to death for the

crime in December of 1999, but that conviction was overturned by the

Missouri Supreme Court in September of 2001. By then Driscoll was 60

and already serving life on other charges, and he was not retried.

Polygraph test

On

February 19, 1999, against his lawyerís advice, Roy Roberts took a

polygraph examination administered by a recently retired Kansas City

Police Department polygraph examiner. Asked whether he had been

involved in the slaying of Thomas Jackson, Roberts answered he had

not, truthfully in the examinerís opinion.

Despite all the doubts about Robertsís guilt,

Carnahan summarily denied his clemency petition.

In addition to the questions about Robertsís

involvement in the Jackson slaying, there is another perplexing

aspect of the case ó the very real possibility that at the time of

the Jackson murder Roberts was in prison for a crime he did not

commit. Another man, Carl Harris, told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch

that he committed the 1978 armed robbery for which Roberts was doing

time. (Other than the armed robbery and the Jackson murder,

Robertsís only other conviction had been for the theft of a radio in

1977.)

Missouri authorities contended that

Harrisís confession lacked credibility because it was not made until

21 years after the crime, long after the statute of limitations had

run on the armed robbery and because Harris and Roberts had been

roommates in 1978. Since Harris could not be prosecuted, the

authorities contended, he might have been lying to help his former

roommate. But the equally plausible theory is that Harris is telling

the truth.

The robber wore a mask, and the victims

identified Roberts by his stature and voice. Harris and Roberts

apparently looked and sounded a lot alike in those days. The victims

easily might have mistaken one for the other. Since there was no

physical evidence linking Roberts to the crime, that makes Roberts's

guilt any more likely than Harris's.

In any event,

there was nothing in the Jackson murder case to make Roberts's guilt

appear more likely than his innocence. Rather, it seems to be the

other way around.

The foregoing summary was prepared by Center

on Wrongful Convictions Executive Director Rob Warden. The summary

may be reprinted, quoted, or posted on other web sites with

appropriate attribution.

Case data:

Jurisdiction: Marion County, Missouri

Date of birth: NA

Date of crime: July 3, 1983

Age at time of crime: 30

Date of arrest: NA

Gender: Male

Race: Caucasian

Trial counsel: Tom Marshall (court-appointed)

Convicted of: Capital murder (prison guard)

Prior adult felony conviction record: Armed robbery (of which

Roberts may have been innocent) 1978; theft, 1977

Trial judge: Ronald R. McKenzie

Key Prosecutor(s):

No. of victims: 1

Age of victim: 62

Gender of victim: Male

Race of victim: Caucasian

Relationship of victim to defendant: Prison guard where Roberts was

incarcerated

Evidence used to obtain conviction: Testimony of prison guard, who

belatedly identified Roberts, and informant testimony

Major issues on appeal: Accomplice liability, sufficiency of the

evidence

Evidence suggesting innocence: Statement of co-defendant that

Roberts was not involved.

Date of execution: March 10, 1999

Time lapse crime to execution: 5,936 days

Final appellate counsel(s): Bruce D. Livingston, Moscow, Idaho, and

Leonard J. Frankel, Clayton, Missouri

Clemency Application of Roy Michael Roberts

In the Offices of the Governor and the Missouri

Board of Pardons and Parole

Roy Michael Roberts, Applicant, v. State of

Missouri, Respondent.

Application of Roy Michael Roberts to Governor

Mel Carnahan for Executive Clemency

Innocent of the crime for which he was convicted

and sentenced to death, applicant Roy Michael Roberts applies to

Missouri Governor Mel Carnahan for an order granting Roberts

executive clemency, or, alternatively, either commuting his death

sentence to life without parole, or staying the execution and

convening a board of inquiry.

Executive clemency exists precisely for cases

like this. Governors who have previously granted clemency to

inmates with claims of innocence did so based on doubt about guilt.

Concern about the horrible possibility that their state might

execute an innocent man forced each of these Governors to the same

conclusion: mercy must be shown and clemency granted if there is any

doubt as to guilt.

"While there is guilt for Ronald Monroe, in an

execution in this country the test ought not be reasonable doubt;

the test ought to be is there any doubt." - Louisiana Governor Buddy

Roemer, quoted in, J. Wardlaw & J. Hodge, "Execution Halted by

Roemer", New Orleans Times-Picayune, Aug. 17, 1989.

"I cannot in good conscience erase the presence

of a reasonable doubt and fail to employ the powers vested in me as

governor to intervene." - Virginia Governor L. Douglas Wilder,

quoted in The Washington Post, Jan. 24, 1992, Sec. D1 (grant of

clemency to Herman R. Bassette Jr.).

"The first question I ask in every case is

whether there is any doubt about the individual's guilt or innocence.

This is the first case since I have been the governor when the

answer to that question was 'yes'.... I take this action so that

all Texans can continue to trust the integrity and fairness of our

criminal justice system."- Texas Governor George W. Bush, Dallas

Morning News, Saturday, June 27, 1998, Editorial, Sec. 24A, story

Sec. 12A. (granting clemency to Henry Lee Lucas).

"There was more than sufficient evidence to show

he was guilty, but there were some questions as far as I was

concerned. I was able to get some information that I know the

judges and jurors did not necessarily receive. Some of the evidence

came in after the trial." - Virginia Governor George F. Allen,

quoted in, The New York Times, Nov. 10, 1996 (commutation of the

death sentence of Joseph Payne).

"My decision finally was reached by some slight

tinge of doubt about both the commission of the crime and the

location of the crime.... I'd have to say in the main that I lean

toward the prosecution side. However, as I mentioned, if there's

the slightest doubt, I'm reluctant to have a man executed." - Idaho

Governor Phil Batt, quoted in, M. Trillhaase, "Batt Spares Paradis'

Life," The Idaho Statesman, May 25, 1996, p. 1A.

A fair and reasoned examination of the facts of

this case must create not just any doubt, but reasonable doubt as to

Roberts' guilt. We implore Governor Carnahan to have the courage to

exercise his clemency powers in this difficult and troubling case,

lest the State of Missouri suffer the shame and infamy of executing

an innocent man.

INTRODUCTION

Roy Roberts was convicted and sentenced to death

for his alleged participation in the stabbing death of a prison

guard, Thomas Jackson, during a July 3, 1983 riot in the state

prison in Moberly, Missouri, the Moberly Training Center for Men.

Roberts was never accused of stabbing Jackson. Roberts was accused

and convicted based on testimony that identified Roberts as the

person who restrained Jackson during the riot while other inmates

stabbed and murdered Jackson. The murder occurred in the midst of

the bedlam and confusion caused by over thirty rioting inmates. Roy

Roberts has always maintained his innocence.

All of the surviving guards, that could identify

who stabbed Jackson, identified Rodney Carr as the stabber. Carr

was convicted of capital murder but received a sentence of life

imprisonment, rather than death. Another inmate, Robert Driscoll,

was also convicted and sentenced to death for stabbing Jackson, but

Driscoll's conviction was reversed in 1995 after it was discovered

that the prosecution had misled the jury into believing that the

dead guard's blood was on Driscoll's knife, when in fact no such

blood was present. See Driscoll v. Delo, 71 F.3d 701 (8th Cir.

1995).

Driscoll has yet to be retried for the crime.

Thus, Roberts is the only person under sentence of death for the

crime, even though he is the least culpable, even under the State's

version of the evidence. This disproportionality pales in

comparison, however, to that which arises if, as we contend, Roberts

is indeed innocent of the crime.

Roberts' claim of innocence is supported by three

main points. First, the initial statements of all the eyewitnesses

against Roberts at trial failed to describe or mention Roberts as

being near Officer Jackson, much less holding Jackson while he was

stabbed. The failure of the eyewitnesses to identify Roberts

initially raises grave doubts about their later testimony against

him. Roberts, a 300 pound behemoth, should have been impossible to

miss while allegedly restraining Jackson in a headlock and crushing

him against a wall and door frame as Jackson was repeatedly stabbed.

Despite the glaring omission of any

identification of Roberts by each of the eyewitnesses against him in

their initial statements, Roberts' counsel failed to cross examine

all but one of those eyewitnesses on that omission at trial. The

negligence of appointed counsel thus precluded the jury from

learning that the eyewitness identifications of Roberts, the only

evidence against him, were thoroughly suspect.

Second, no physical evidence ties Roberts to the

bloody scene of Jackson's death, where Roberts' allegedly restrained

Jackson in a headlock while he was stabbed in the eye, heart and

abdomen. Though the guards were on the lookout for bloody clothes,

and indeed confiscated such clothes from Robert Driscoll, Roberts'

clothes were scrutinized after the riot, but were not confiscated

because they were not bloody.

Third, on February 19, 1999, to prove his

innocence, Roy Roberts took a polygraph (lie detector) test,

administered by a well-respected, retired Kansas City police officer/polygrapher.

Despite being under the stress of a warrant for execution, Roberts

passed the polygraph. His test results showed "no deception" in his

answers denying involvement in the murder, including specific

denials that he was holding the victim during the stabbings.

All attempts at relief in the courts have failed.

An appeal for clemency to Governor Carnahan is Roberts' only hope.

DOUBTS ABOUT ROBERTS' GUILT AND THE POSSIBILITY

THAT HE IS INNOCENT COMPEL THE EXERCISE OF THE GOVERNOR'S CLEMENCY

POWERS TO PREVENT ROBERTS' EXECUTION.

A. THE "EYEWITNESS" IDENTIFICATIONS AT TRIAL ARE

INHERENTLY UNRELIABLE AND SUSPECT.

At Roberts trial, four witnesses testified in the

guilt phase that Roberts was holding Jackson when Jackson was

stabbed. Three witnesses were guards, Denver Halley, Robert Wilson

and Wayne Hess, and one was an inmate, Joseph Vogelpohl. At first

blush, four eyewitnesses might seem like a strong case for guilt.

The facts are otherwise.

As set forth in greater detail below, each of

these four witnesses gave initial statements shortly after the riot

which omitted any mention or description of Roy Roberts. The

inability of anyone to identify Roberts as the inmate who restrained

Jackson in the two weeks following the riot is particularly

troubling, given Roberts' easily recognized size at the time of 300

pounds. Further, and of great significance to the fairness of

Roberts' trial, his appointed lawyer, Tom Marshall, failed to

question these witnesses, save one, about their prior inconsistent

statements. The jury was led to believe that the eyewitness

identifications of Roberts were far more reliable and trustworthy

than was in fact the case.

Before addressing the specifics of the

eyewitnesses failure to describe or name Roberts initially in their

individual statements, it is worthwhile to put the scope and extent

of the murder investigation in perspective by examining the summary

report by the Department of Corrections' internal affairs

investigator, Mark Schreiber. Two weeks after the riot, Schreiber

submitted a 17 page internal investigation report of the murder.

That memo does not mention Roy Roberts.

The report confirms that nobody knows who, if

anyone, was holding Jackson while he was being stabbed. The DOC's

report on the riot, dated July 18, 1983, is telling in its omission

of any mention of Roy Roberts, and in its suggestion that hypnosis

be used to identify more suspects. Schreiber's report concluded

that additional participants might not ever be identified, because

of difficulties in identifying any other assailants of Officer

Jackson, other than, of course, those mentioned in the Supplemental

Report, inmates Driscoll and Carr. Schreiber's conclusion bears

reprinting in its entirety here, as it underscores the completeness

of the investigation to that point, makes the candid assessment that

no further suspects were likely to be identified, and significantly

undermines the credibility of the subsequent identification

testimony against Roberts:

Conclusion

Every investigative effort has been and is being

made to determine the identity of and to bring to justice the

individual or individuals who are responsible for the death of CO/I

Thomas Glen Jackson and the subsequent assaults upon other

correctional officers at MTCM on July 3, 1983. Due to the number of

inmates who were intoxicated and who, to varying degrees

participated in the riot, the full extent of the number and identity

of those involved may never be known. The greatest obstacle which

has hampered ongoing investigation thus far has been the inability

of potential eyewitnesses to remember anything as to the identity of

the officers' assailants. This is not to say that the officers have

not honestly made such attempts. The hard facts are that when one

is fighting for life itself there is no time to sit down and take

notes.

It was suggested by Sgt. L. Dale Belshe that

perhaps it might be beneficial if the officers involved were to be

placed under hypnosis if they are willing. I feel that such an

investigative procedure might be of benefit. Sgt. Belshe has

indicated that he is willing to make the arrangements.

A continued effort will be made to identify any

individual who was involved in the acts of violence which took place

on July 3, 1983. The important factor in an investigation of this

magnitude is not who or what agency receives the credit but that

agencies working together as a single effective investigative unit

do all that is possible within the realm of police science to solve

the problem for the benefit of all concerned.

Memo to W. David Blackwell from Mark S. Schreiber,

dated July 18, 1983, Re: Supplemental Investigation - MTCM Incident

of July 3, 1983, at p. 17 (emphasis added). Memo Attached as

Exhibit A.

Roberts has never denied that he was involved in

the riot and engaged in fisticuffs with prison personnel. Officer

Kroeckel testified that he and Roberts fought in a fist-fight in the

control center, Trial Transcript ("TT") at 243-45. This Roberts did,

along with 20-40 other inmates, many of whom have presumably served

their sentences and are now walking the streets of Missouri. See TT

at 240 (testimony of Officer Kroeckel that 20-30 inmates were

fighting in the control center); id. at 317 (testimony of Officer

Hess that 25-40 inmates involved); id. at 372 (testimony of Officer

Humphrey that 30-35 inmates involved).

What Roberts did not do was hold Officer Jackson

while he was being stabbed and thereby prevent Jackson's escape from

whatever murderous inmate was stabbing him. Many inmates testified

that Roberts did not restrain Jackson. They are not alone. Officer

Kroeckel acknowledged that Roberts fought with him, and agreed that

he did not see Roberts holding Jackson. TT 245.

The testimony of four people convicted Roy

Roberts of the crime for which he is sentenced to die. Examination

of their initial statements and comparison to each person's trial

testimony reveals how radically different the trial testimony is.

Clearly, the witnesses in this case got their story "straight" over

time and aimed it directly at Roy Roberts. Such "evolving"

testimony is inherently suspect and raises serious doubts of Roberts'

guilt.

Captain Denver Halley was the ranking officer

during the riot. He testified at trial that from a foot away

through the glass window, TT 254, he saw Roberts hold Jackson "by

the arm and also by the hair of the head and keeping him right up

against the door casing." TT 256. Halley testified that "while

Roberts was holding him, I would see Jackson jerking and blood

getting all over him." TT 257. Halley further testified that when

Halley attempted to rescue Jackson, Roberts let go of Jackson to hit

Halley, and thereafter, Roberts re-took his hold on Jackson. TT

257-58. Excerpts of Halley's trial testimony are attached as Ex. B.

After the riot, Halley wrote a report that

night. TT 269; Transcript of Rule 27.26 Motion Hearing ("PCR TR")

at 29. Excerpts of Halley's PCR TR testimony are attached as Ex. C.

Halley's signed report, dated 3:17 a.m. on July 4, 1983, is attached

as Ex. D ( originally marked as PCR TR Ex. 11). At the time of the

riot, Halley knew Roberts. PCR TR 36, Ex. C. Moreover, he later

described Roberts as standing out "like a red rose in the Sahara

desert." Deposition of Denver Halley in the Robert Driscoll case at

9, excerpt attached as Ex. E.

Despite Roberts' great size and the specificity

of later trial testimony, Halley failed to mention Roberts in his

initial statement on July 4. Ex. D. Halley identified only a mob

of inmates, no individuals, and stated that "they" were holding him.

Id.

They [Goodin and Kroeckel] arrived at the steps

leading out of the wing with this inmate, and he went to hollering

and [at] that time approximately 35 or maybe 40 inmates came running

to us. They grabbed Officer Tom Jackson first and had him up

against the door, and approximately, I would say, 12 or 14 inmates

were trying to come out into the Rotunda. Officer Goodin, Officer

Wilson, Lt. Kroeckel, and myself -- Captain Halley -- we went to

fighting these inmates. a number of them were armed with iron bars

and knives. I attempted to help Officer Jackson get away from the

inmates. They were holding him and during this procedure, I was

knocked down twice, plus was hit in the arm with a pipe. I heard

Officer Jackson holler and I finally managed to drag him out. He

was bleeding profusely and I dragged Officer Jackson across the

Rotunda and knew at that time that he was dying.

Ex. D, Statement of Denver Halley dated July 4,

1983 (emphasis added).

Sixteen days later and two days after DOC

Internal Affairs investigator Mark Schreiber submitted his report,

Ex. A, Halley submitted an investigation report identifying Roberts

for the first time as "one of the inmates" holding Officer Jackson.

Ex. F, Halley statement dated July 20, 1983.

Two days after the DOC report acknowledged that

no more inmates were likely to be identified, Halley selected the

biggest and most noticeable inmate to have been in the riot and

suddenly implicated him as one of the persons holding Roberts. The

evolution of Halley's testimony had begun. That evolution continued

and culminated with Halley's trial testimony, in which he stated

that Roberts, alone, was holding Jackson.

Correctional Officer Robert Wilson likewise

testified at trial that Roy Roberts held Jackson around the neck, TT

296, and that Roberts was the one preventing Jackson from getting

away. TT 299 (Wilson trial excerpts attached as Ex. G). Wilson's

initial statements are far different:

Officer TG Jackson, KF Goodin & DL Kroeckel went

in B wing and brought out a man who was intoxicated.

As they was bring the man out the door about 30 t

40 inmates busted out the wing door after us. I grabbed one inmate

by the head and was hitting him. He came out with a knife and cut

me on the left hand. Then (S) went for officer T.G. Jackson. At

this time Officer Humphrey hit him with bat & (S) went down.

The other inmates drug back into the wing.

By then I was fighting with anoughter (sic)

inmate & the other officers got the wing locked down.

Ex. H, Wilson Statement, dated 2:30 a.m on July

4, 1983. Obviously, there is no mention of Roberts in this

statement. Nor is there any mention of Roberts in Wilson's next

statement, which is much more complete and states in pertinent part:

As they were bringing the drunken inmate out of

the wing approximately 35 inmates rushed us. Inmate Rodney Carr #

38428 rushed out the door toward myself. I grabbed inmate Carr

around the neck from behind and started hitting him with my

flashlight. He pulled a shank and cut me across the left hand

freeing himself from my grip. Lunged forward approximately 3 feet

sticking Officer Jackson in the chest area.

At this time Officer Hess grabbed inmate Carr and

they began to scuffle. Carr got in behind Hess and stuck him in the

right shoulder. Officer Humphry hit inmate Carr behind the head

with a ballbat knocking him to the floor. Carr then dropped the

shank as he fell. At this time an unknown inmate hit me in the

right shoulder knocking me to the floor. as I was getting up I

picked up the shank that Carr had dropped and stuck it in back of my

belt. Inmates began dragging Carr and other inmates back into the

wing giving us enough time to get the wing doors shut and locked.

Myself, Officer Kroeckel and Halley placed

Officer Jackson onto a stretcher [illegible] to the prison

hospital. Officer Humphry Lt. Kroeckel and a inmate accompanied

Officer Jackson to the hospital. Capt. Halley and a new officer by

the name of Dillon ran to the administration building to get

shotguns and more help. Myself, Officer Goodin and Officer Hess

stayed back to hold down the house. Inmates from all four wings

were hollering, breaking glass and preparing to come into the

Rotunda after us. After approximately 10 minutes Capt. Halley,

Officer Dillon and Lt. Arney returned with shotguns. The order was

given for the inmates to return to their cells. Some of them did,

most did not! At this time Capt. Halley & Lt. Arney & myself began

firing into the wings & the inmates ran for their cells.

Ex. I, Wilson statement, dated July 10, 1983.

More than two months later, Wilson's statement was virtually the

same, still without any reference to Roberts. Ex. J, Report of

Officers Merritt and Ullery dated September 13, 1983 (previously

identified as PCR TR Ex. 6).

Wilson admitted that he "knew" inmates Carr and

Roberts. Ex. K, Robert Wilson deposition in Robert Driscoll case at

5-6. Yet despite this knowledge and Roberts' large size, Wilson

named only Carr and failed to identify Roberts in either of Wilson's

initial statements.

Wayne Hess, too, failed to identify Roberts in

his initial statements. He gave two statements, one dated July 4,

1983, Ex. L, and another dated July 9, 1983. Ex. M. In the July 4

statement, Hess stated that "three or four inmates had ahold of his

[Jackson'] head and tried to pull him back into the wing." Ex. L,

p. 3. Hess was "right beside him," but Hess did not know any of

those inmates. Id. Hess only remembered Carr and affirmatively

stated that he did not remember any other inmates that were directly

involved in the incident. In the July 9 statement, Hess states that

"some of the inmates had Jackson in a headlock." Ex. M, p. 2. He

then went on to say that the next day he had been shown photos of

inmates, "one I remember was Carr, I think Driscoll, Batey or

something like that, and one other I don't remember. I looked at

one picture of Carr and I stated this was the man who done the

stabbing." Ex. M, p.3.

Hess' failure to identify Roberts in these

statements is particularly significant, because Prosecutor Finnical

admitted in the Rodney Carr trial that Hess was shown a photograph

of Roy Roberts before Hess went to the line-up on July 4. Ex. N,

Hess testimony from trial of Rodney Carr. Thus, Hess failed to

identify Roberts as an inmate who restrained Jackson in a statement

made shortly after Hess was shown Roberts' picture on July 4, Ex. L,

and again on July 9. Ex. M.

The prosecution attempted to hypnotize Hess to

bolster his memory, Ex. O (PCR TR Ex. 3), and still he did not

identify Roberts. Ex. O at 6, 12. Hess could not identify Roberts

in Hess' initial statements, notwithstanding that he admitted that

he knew "Hog" Roberts as the largest man in the wing and knew him by

that name. Ex. P, Hess' 27.26 testimony at 16-18.

Nevertheless, Hess' testimony at trial was very

specific, alleging that Roberts, a man he had "seen around" before

and who weighed "about 300 pounds," had Jackson "in a headlock and

Tom Jackson couldn't get away to defend himself." TT 305. Given

these circumstances, Hess' trial identification of Roberts is

particularly dubious.

Inmate Joseph Vogelpohl was the only other

witness who identified Roberts in the guilt phase as the person who

restrained Jackson while he was stabbed. Vogelpohl, too, was unable

to identify Roberts initially. In Vogelpohl's initial statement on

July 4, 1983, Ex. Q, he totally failed to mention Roy Roberts.

Despite his later claim to having witnessed Jackson's murder, all he

said in his initial statement was that: he'd seen Robert Driscoll

assemble a knife in his cell; then, while near the rotunda from five

feet away he saw Driscoll "punch at" Officer Jackson; and finally,

he'd returned to his cell, where Driscoll also returned and said to

Vogelpohl that Officer Jackson "had got stuck." Ex. Q.

In his statement Vogelpohl announced that he was

making a statement so that he wouldn't "take the rap" for the crime.

Id. In his subsequent statement to Officers Merritt and Ullery on

October 3, 1983, Vogelpohl stated that Driscoll and John Bolin were

the inmates who stated that the inmates should stop the guards from

taking Jimmy Jenkins out of the wing, and that Bolin said "let's

rush them." TT 341. Vogelpohl also wrote a letter to a friend,

Dewitt Burns, saying that he heard that Ed Ruegg, not Roberts, had

held Jackson. TT 335.

At trial, however, Vogelpohl's testimony turned

on Roberts. First, he stated that Roberts had been the person who

suggested that the inmates should "rush" the guards. TT 326-27.

Then he stated that Roberts had stopped Jackson at the wing door, TT

328, and that he had seen Driscoll stab Officer Jackson while

Roberts held him. TT 329. Excerpts of Vogelpohl's testimony is

attached as Ex. R. Vogelpohl's evolving testimony should be seen

for what it was, an attempt to evade "the rap" for being in a riot

five feet from the murdered guard, and an attempt to curry favor to

get paroled early.

Thus, by the time of trial, the State presented

four witnesses in the guilt phase who gave relatively unambiguous,

chilling testimony that placed Roberts at the scene as the one and

only person restraining Jackson. The dramatic change in the

specificity of these witnesses from the time of the riot until trial,

in which their stories coalesced and "matured" into adamant

certainty that Roberts restrained Jackson and was the sole person to

do so, by itself creates significant questions about Roberts' guilt.

The changes in testimony are too dramatic to be believed and seem to

confirm the rumor that Prosecutor Finnical was out to get "three for

one," no matter what the cost in terms of integrity or reliability.

The questions raised by the changes in testimony creates a

reasonable inference that the State of Missouri may be intending to

execute a man who may well be innocent.

B. NO PHYSICAL EVIDENCE CONNECTS ROY ROBERTS TO

THE MURDER OF OFFICER JACKSON.

No physical evidence connects Roy Roberts to the

murder of Officer Jackson. It is uncontroverted that Roberts did

not have a weapon. Despite the extensive amount of blood spilled by

Officer Jackson, there is no evidence of any blood on Roberts or his

clothes. It defies belief that Roberts could have restrained

Jackson as described by the adverse eyewitnesses, and not gotten

blood on himself.

Roberts was described as having Jackson around

the neck, TT 296 (testimony of Wilson), in a headlock, TT 305 (testimony

of Hess), and "by the arm and also by the hair of the head and

keeping him right up against the door casing." TT 256 (testimony of

Halley). The bleeding from Jackson was profuse. Halley described

it as "while Roberts was holding him, I would see Jackson jerking

and blood getting all over him." TT 257.

The blood was "all over the front and side of

Jackson's shirt" and was "very, very obvious." TT 258. Halley said

that Jackson looked like a "butchered hog." TT 281. Jackson's

shirt looked like "solid blood." TT 375 (testimony of Officer

Humphrey). Given Roberts' supposed close contact with Jackson and

the amount of spilled blood, Roberts should have been soaked with

blood.

After prison guards quelled the riot, the inmates

were locked into their cells. TT 266 (Halley testimony).

Thereafter each room was searched, and the inmates were personally

searched. TT 267. Robert Driscoll's clothes were collected from

his room and analyzed because they appeared to be covered with blood.

See Driscoll v. Delo, 71 F.3d 701, 707 (8th Cir. 1995) (blood

analysis conducted on the recovered knives, Officer Jackson's

clothes, "and the clothes worn by various inmates, including

Driscoll, on the night of the riot"). Notably, Roberts' clothes

were not saved, tested or ever offered into evidence against him.

The fact that Roberts clothes were not tested or

confiscated directly correlates to the absence of blood on them. At

the time of the riot, Willie Dennis was a major at the Moberly

prison. On February 20, 1999, Dennis spoke with Roberts'

investigator, Richard S. Hays of the Federal Defenders of Eastern

Washington and Idaho. Major Dennis told Mr. Hays that he arrived at

the prison within an hour of the death of Officer Jackson and

relieved the guards that were involved in the initial disturbance.

Major Dennis acknowledged that he supervised the

removal and transfer of inmates from their cells in Wing B who were

thought to have been involved in the riot. Major Dennis

acknowledged that he supervised the removal of Roy Roberts from his

cell, and that he saw no blood on Roberts. Major Dennis further

stated that he would have confiscated any article of clothing or

other item for evidence, if blood was on it. Affidavit of Richard

S. Hays, attached as Ex. T. Major Dennis' claim that he was looking

for blood on clothes is corroborated by the record of confiscated

clothes in this case. See Driscoll v. Delo, 71 F.3d at 707.

The absence of blood on Roberts' clothes raises

serious questions about his participation in the murder of Officer

Jackson. The likelihood that the witnesses are correct in their

description of Roberts' alleged restraint of Jackson is highly

improbable.

C. ROY ROBERTS PASSED A POLYGRAPH TEST THAT

INDICATED "NO DECEPTION" WHEN HE DENIED INVOLVEMENT IN JACKSON'S

MURDER AND DENIED RESTRAINING JACKSON WHILE JACKSON WAS BEING

STABBED.

To prove his innocence, Roy Roberts insisted upon,

took and passed a polygraph (or lie detector) test on February 19,

1999 at the Potosi Correctional Center while under a warrant of

execution set for March 10, 1999. Despite the stress involved in

taking a test under those conditions, Roberts' test results were

clear: "no deception" in his denial of involvement in Jackson's

murder.

Donald I. Dunlap, A.C. P., administered the

polygraph test. Mr. Dunlap retired after thirty years with the

Kansas City, Missouri Police Department. Dunlap served as a

polygrapher for the last 24 years of his service with the Kansas

City Police Department. He spent nine years as a full-time

polygrapher, followed by more than 15 years as Chief Polygraphist of

the department. Since Dunlap's retirement in 1985, he has worked in

private practice, presently under the name of Don Dunlap &

Associates. He is a highly respected polygrapher who has continued

to work for law enforcement, such as the Benton County Sheriff's

Department, as well as the Missouri Public Defender's Office, and

various private attorneys. His resume is attached as Ex. U.

The polygraph report of the Roberts examination

on February 19th is attached as Ex. V. That report reaches the

following conclusion:

It is the opinion of the polygraphist that

deception was not indicated in this person's polygraph records when

he answered the following questions as indicated:

1. When Jackson was being stabbed, were you

holding him in any way? Answer, No.

2. When Jackson was being stabbed, were you

holding him by the hair? Answer, No.

3. Just before Jackson was stabbed, did you pin

him against a door casing? Answer, No.

4. While Jackson was being stabbed, did you have

any physical contact with him? Answer, No.

Ex. V, Letter Report of Don Dunlap & Associates

to Bruce D. Livingston, dated February 20, 1999, Re: Roy Michael

Roberts Polygraph Interview.

The U.S. Supreme Court recently addressed the

admissibility of polygraph evidence in the military courts. United

States v. Scheffer, 118 S.Ct. 1261 (1998). The Supreme Court

recognized the trend toward admissibility of such evidence, 118 S.Ct.

at 1265-66, though the Court declined to recognize a constitutional

right to present polygraph evidence based on a lack of consensus

within the lower courts on the reliability of polygraphs. Id. In

dissent, Justice Stevens compiled the evidence on the reliability of

polygraphs:

There are a host of studies that place the

reliability of polygraph tests at 85% to 90%. While critics of the

polygraph argue that accuracy is much lower, even the studies cited

by the critics place polygraph accuracy at 70%. Moreover, to the

extent that the polygraph errs, studies have repeatedly shown that

the polygraph is more likely to find innocent people guilty than

vice versa. Thus, exculpatory polygraphs -- like the one in this

case -- are likely to be more reliable than inculpatory ones.

Scheffer, 118 S.Ct. at 1276 (Stevens, dissenting)

(footnotes omitted) (emphasis added). Like the defendant in

Scheffer, Roberts, too, passed the more reliable polygraph-- an

exculpatory one. See Scheffer, 118 S.Ct. at 1276 n.22 (compiling

studies that show exculpatory polygraphs to be more reliable than

inculpatory polygraphs).

The polygraph that Roberts passed was reliable

not only because it was exculpatory, but also because the

examination was administered by a respected, experienced, former

member of law enforcement, Don Dunlap. As the chief Polygraphist

for the Kansas City Police Department for over 15 years, Dunlap's

qualifications are impeccable. As a former police officer, Dunlap

is decidedly unlikely to be inclined to favor an accused guard-killer

through questionable interpretations of the test results. Dunlap's

finding that Roberts passed an exculpatory polygraph test is

powerful additional evidence that Roberts is innocent of the crime

for which he has been sentenced to death.

Clemency proceedings have turned upon polygraph

results previously. Virginia Governor Douglas Wilder would have

granted clemency to Roger Coleman in 1991, had Coleman passed a

polygraph test. J. Tucker, "May God Have Mercy: A True Story of

Crime and Punishment," W.W. Norton & Co. (1997), at 280-81, 300-01.

When Coleman failed to pass the polygraph, Governor Wilder declined

to intervene. Id. at 312. Coleman's polygraph was given under

extreme circumstances, hours before his scheduled execution. Id. at

305-14. Though that test, which was inculpatory, suffered from more

significant reliability concerns than Roberts' exculpatory polygraph,

it provides precedent for considering polygraph results in making a

clemency decision.

Given the greater reliability of Roberts'

exculpatory polygraph, one must have serious doubts about his guilt.

Roberts' polygraph result strongly supports his claim of innocence

and provides Governor Carnahan with yet another reason to intervene

in this case.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, Roberts implores Governor Carnahan

to stop the execution scheduled for March 10, 1999. Roy Roberts

deserves clemency, and at least commutation or a board of inquiry.

The State of Missouri must not proceed with this execution. The

possibility that Roberts may be innocent is too real. Allowing

Missouri's machinery of death to continue to operate, wheeling an

innocent man on a gurney to the execution chamber in Potosi, is too

horrible to contemplate -- the ultimate miscarriage of justice.

This application for clemency raises doubts about Roberts' guilt,

significant doubts. Those doubts cry out for Governor Carnahan's

intervention and mercy. Let not Missouri be the State that

knowingly executes an innocent man.

We urgently and respectfully request that

Governor Carnahan halt the execution of Roy Michael Roberts.