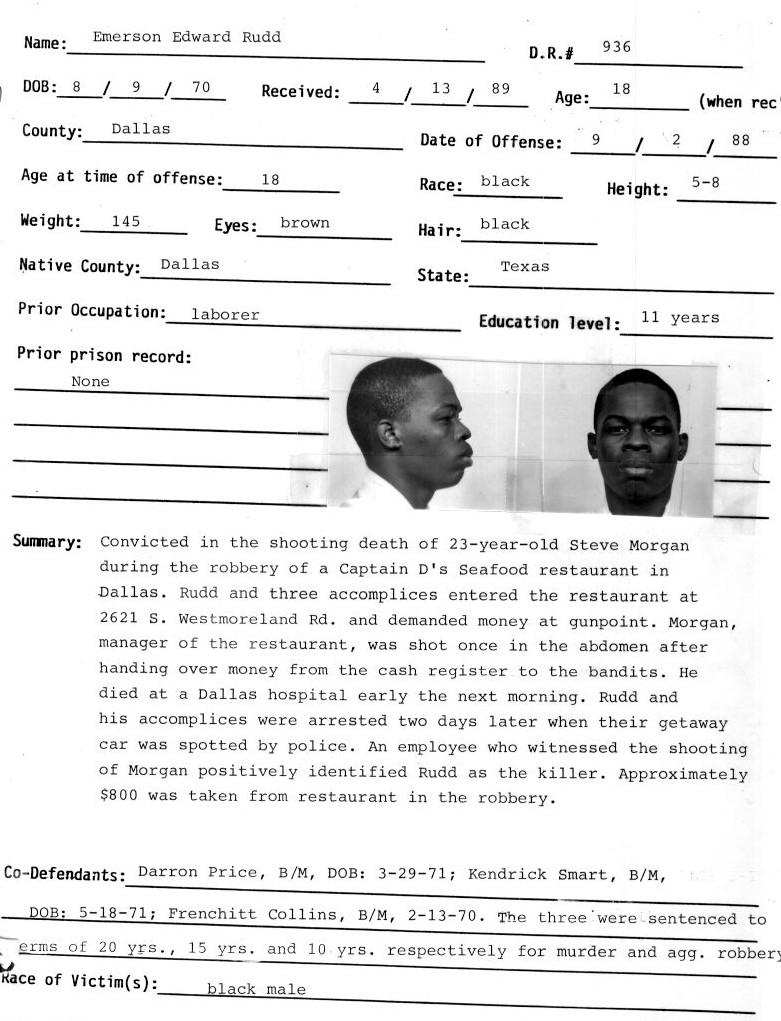

Applicant-Appellant Emerson Edward Rudd, a Texas death row inmate, whose petition for habeas corpus relief and request for a Certificate of Appealability ("COA") were both denied by the federal district court, now seeks a COA from this Court pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2253(c)(2). For the reasons set forth below, we deny Rudd's application for a COA.

I. BACKGROUND

On the evening of September 2, 1988, Rudd and three others robbed a Captain D's restaurant in Dallas, Texas. During the course of the robbery, Rudd intentionally shot one of the restaurant's managers when that manager told Rudd that Captain D's had no large amounts of money. The manager died later that night at a local hospital. After robbing the Captain D's, Rudd and his cohorts committed another aggravated robbery at another restaurant.

Rudd was ultimately tried and convicted of capital murder in state court. He was sentenced to death, and the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed his conviction on direct appeal. Rudd filed a timely post-conviction writ of habeas corpus with the trial court under Article 11.071 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure. The trial court entered findings of fact and conclusions of law adverse to Rudd, which the Court of Criminal Appeals adopted.

Thereafter, Rudd filed his federal petition for writ of habeas corpus on May 1, 1998. The district court referred the matter to a magistrate judge. On September 8, 2000, the district court adopted the magistrate judge's report and recommendation that Rudd's petition be denied. Rudd filed his notice of appeal and motion for a COA on October 12, 2000. The district court denied the COA request on November 13, 2000. As a result, Rudd filed the instant application for a COA on January 3, 2001.

II. DISCUSSION

Rudd filed his petition for a writ of habeas corpus on May 1, 1998. Consequently, it is governed by the provisions of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act ("AEDPA"). See Lindh v. Murphy, 117 S. Ct. 2059(1997). Under the AEDPA, before an appeal from the dismissal or denial of a § 2254 habeas petition can proceed, the petitioner must first obtain a COA, which will issue "only if the applicant has made a substantial showing of the denial of a constitutional right." See 28 U.S.C. § 2253(c)(2).

An applicant makes a substantial showing when he demonstrates that his application involves issues that are debatable among jurists of reason, that another court could resolve the issues differently, or that the issues are suitable enough to deserve encouragement to proceed further. See Clark v. Johnson, 202 F.3d 760, 763 (5th Cir.) (citing Drinkard v. Johnson, 97 F.3d 751, 755 (5th Cir. 1996), overruled in part on other grounds, Lindh, 117 S. Ct. 2059), cert. denied, 121 S. Ct. 84 (2000).

Specifically, if a district court rejects a prisoner's constitutional claims on the merits, the applicant must demonstrate that reasonable jurists would find the district court's assessment of the constitutional claims debatable or wrong. See Slack v. McDaniel, 120 S. Ct. 1595, 1604 (2000). If the district court denies a habeas petition on procedural grounds without reaching the prisoner's underlying constitutional claim, then a COA should issue when the prisoner shows, at least, that jurists of reason would find it debatable whether the petition states a valid claim of the denial of a constitutional right and that jurists of reason would find it debatable whether the district court was correct in its procedural ruling. Id. But because the present case involves the death penalty, any doubts as to whether a COA should issue must be resolved in Rudd's favor. See Clark, 202 F.3d at 764.

Unless rebutted by clear and convincing evidence, a state court's determination of a factual issue shall be presumed to be correct. See 28 U.S.C. § 2254(e)(1); Davis v. Johnson, 158 F.3d 806, 812 (5th Cir. 1998). The presumption is particularly strong when the state habeas court and the trial court are one and the same. See Clark, 202 F.3d at 764.

In his application, Rudd presents three issues for which he seeks a COA: 1) whether he was denied due process when he was not permitted access to the State's file; 2) whether he was denied his constitutional rights by the trial court's jury instructions at the punishment phase; and 3) whether he was denied the effective assistance of counsel by his trial counsel's alleged failure to elicit crucial mitigating testimony from two witnesses at the punishment stage of trial. We now address those issues in light of the standards for the issuance of a COA.

A. Access To The State's Case File

Rudd first argues that he was denied due process when he was not permitted access to the State's case file during his state habeas proceeding. Subsumed within this argument is another claim that the Court of Criminal Appeals' routine denial of motions to compel without prejudice to file in trial court effectively denies equal protection of the laws and creates unequal results because individual trial courts now have the discretion to determine whether defendants should have access to the State's case files.

We cannot grant Rudd a COA on this two-pronged issue. A long line of cases from our circuit dictates that "infirmities in state habeas proceedings do not constitute grounds for relief in federal court." Trevino v. Johnson, 168 F.3d 173, 180 (5th Cir.) (quoting Hallmark v. Johnson, 118 F.3d 1073, 1080 (5th Cir. 1997)) (internal quotation marks omitted), cert. denied, 120 S. Ct. 22 (1999); Nichols v. Scott, 69 F.3d 1255, 1275 (5th Cir. 1995); Duff-Smith v. Collins, 973 F.2d 1175, 1182 (5th Cir. 1992); Millard v. Lynaugh, 810 F.2d 1403, 1410 (5th Cir. 1987); see also Vail v. Procunier, 747 F.2d 277, 277 (5th Cir. 1984).

That is because an attack on the state habeas proceeding is an attack on a proceeding collateral to the detention and not the detention itself. Nichols, 69 F.3d at 1275. Rudd does not question the unavailability of the State's case file during the trial, but rather, its unavailability during his state habeas proceeding. Accordingly, his challenge is merely an attack on infirmities in the state habeas proceeding and is foreclosed by our circuit precedent. Hence, Rudd has not made a substantial showing of the denial of a constitutional right, and his application for a COA on his first issue is denied.

B. Jury Instructions

In his second issue for which he seeks a COA, Rudd argues that he was denied his constitutional rights by the trial court's jury instructions at the punishment phase.1 This claim is also two-headed. First, Rudd maintains that the jury instructions violated the Eighth Amendment doctrine of heightened reliability because they did not provide the jury with any guidance about the meaning of a life sentence and, therefore, allowed the jury to speculate about the length of such a sentence. Second, he contends that the jury instructions violated his due process rights.

According to Rudd, his entire argument that he did not pose a future danger and, thus, should not be executed was premised on the State's alleged failure to present evidence suggesting that he would be a danger in prison society. But Rudd charges that the trial court's jury instructions induced the jury to speculate about Rudd's parole eligibility. As a result, the future dangerousness issue extended to free society, and Rudd contends that he should have been afforded the opportunity to rebut the State's argument by showing the jury that he would not have been eligible for parole for at least fifteen years.

To support his claim, Rudd principally relies on Simmons v. South Carolina, 114 S. Ct. 2187 (1994). In Simmons, a death penalty case, a plurality of the Supreme Court observed that "where the defendant's future dangerousness is at issue, and state law prohibits the defendant's release on parole, due process requires that the sentencing jury be informed that the defendant is parole ineligible."2 Id. at 2190. It, however, did not delve into situations, such as here, where parole may be available. Id. at 2196. A compelling reason for the plurality's holding was that "[t]he Due Process Clause does not allow the execution of a person 'on the basis of information which he had no opportunity to deny or explain.'" Id. at 2192.

More precisely, the plurality was concerned that the jury instructions in Simmons created a mistaken understanding on the part of the jury that it could only sentence the defendant to death or sentence him to a limited period of incarceration. Id. at 2193. As that was a false choice, the defendant had to have the opportunity to deny or explain his situation by proffering an instruction that he was ineligible for parole. Id.

Here, the jury did not confront a false choice that needed to be denied or explained. Under Texas law, Rudd would have been eligible for parole after serving fifteen years in prison. Contrary to Simmons, the jury would not have been mistaken if it believed that it could only sentence Rudd to death or to a limited period of incarceration. And a jury instruction on Rudd's parole eligibility would not have denied or explained the State's argument that Rudd was a future danger to free society.3

Unlike in Simmons, where the defendant was ineligible for parole and had virtually no chance of being released from prison, a jury instruction in the instant case would not have explicitly denied or rebutted the State's argument that Rudd was a future danger to free society because Rudd would have been eligible for parole. Although Rudd believes that information about his parole eligibility after fifteen years could have made a great deal of difference, "how the jury's knowledge of parole availability will affect the decision whether or not to impose the death penalty is speculative." Simmons, 114 S. Ct. at 2196. In fact, a jury instruction on parole eligibility could just as well have reinforced the State's argument about future dangerousness because Rudd would have been eligible for parole at the fairly young age of thirty-three.

Likewise, we found Simmons unavailing in a case similar to Rudd's. See Miller v. Johnson, 200 F.3d 274 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 121 S. Ct. 122 (2000). In Miller, the defendant argued that, "had the jury been informed that a life sentence would require him to spend fifteen calendar years in prison before becoming eligible for parole, a member of the panel could have been convinced that he would not pose a future danger." Id. at 290. We noted that "Simmons requires that a jury be informed about a defendant's parole ineligibility only when (1) the state argues that a defendant represents a future danger to society, and (2) the defendant is legally ineligible for parole." Id. at 290. (emphasis added).

Because Simmons is distinguishable and because Rudd fails to cite any other cases directly supporting his position, we return to our long-held precedent that "'neither the due process clause nor the Eighth Amendment compels instructions on parole in Texas.'" Id. at 291 (quoting Johnson v. Scott, 68 F.3d 106, 112 (5th Cir. 1995)). Accordingly, we see no substantial showing of the denial of a constitutional right based on the trial court's jury instructions at the punishment phase and deny Rudd's request for a COA on his second issue.

C. Ineffective Assistance Of Counsel

Rudd's final issue for which he seeks a COA concerns his trial counsel's alleged failure to elicit crucial mitigating testimony from two witnesses at the punishment stage of trial. Specifically, he charges that his counsel failed to elicit from his cousin Tamekka Whitmore and his sister Olivia Rudd certain testimony about his father's improprieties, including raping and abusing his mother, stealing from the family, and being found in bed with another woman. Because of that purported failure, Rudd argues that his counsel was ineffective under the standard announced in Strickland v. Washington, 104 S. Ct. 2052 (1984).4

To satisfy the Strickland standard, a defendant must show 1) that his counsel's performance was deficient and 2) that the deficient performance prejudiced his defense. Id. at 2064. Having reviewed pertinent portions of the record and in light of the deferential standard of review accorded the state habeas court's findings, we conclude that Rudd has not made out a substantial showing that his Sixth Amendment right to counsel was violated.

Several individuals testified on behalf of Rudd at the punishment phase, including Whitmore and Olivia Rudd. Both of those women recounted how Rudd came from a disadvantaged background and had suffered physical abuse from his father. Moreover, testimony at trial indicated that Rudd grew up in an environment full of drugs, prostitution, and violence. Thus, Rudd's counsel devoted a substantial amount of attention and resources to draw a picture of Rudd's impoverished childhood and inadequate parenting, which are the same things that Whitmore's and Olivia Rudd's testimony would have supported.

Here, the fact that not every item of so-called mitigating evidence was not provided to the jury does not make Rudd's counsel's performance deficient, especially when there is no proof that either Whitmore or Olivia Rudd told Rudd's counsel everything. Rudd responds that we should not place the onus on the witnesses for failing to come forth with all of the mitigating evidence.

According to him, a witness does not choose what she will testify to, but only answers questions propounded by the counsel; hence, the burden should be on the counsel to ask the appropriate questions and to elicit information in support of the defendant's case. But when the record undeniably reveals that trial counsel attempted to elicit information similar to that which was withheld and the witnesses do not testify to those other items or fail to disclose them, we cannot fault trial counsel for not providing every piece of evidence remotely connected to mitigation.

Furthermore, Rudd has not substantially shown that prejudice resulted from his counsel's performance. The substance of Whitmore's and Olivia Rudd's new testimony was essentially presented to the jury. They would have been cumulative and would not necessarily have resulted in a life sentence rather than a death sentence.

As Rudd's counsel's performance was neither deficient nor prejudicial, we deny a COA on his third and final issue.

III. CONCLUSION

Rudd has failed to make a substantial showing of the denial of a constitutional right with respect to the three issues raised in his application for a COA; therefore, his application is DENIED.

*****

NOTES:

According to Rudd, the trial court's failure to instruct on parole eligibility, i.e., define "life in prison," spurred speculation on the part of the jury. In addition, he maintains that the trial court's definition that society "also includes the Texas Department of Corrections," induced the jury to include free society and to speculate about parole.

This quote is from the plurality opinion by Justice Blackmun, but Justice O'Connor's concurrence, in which Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justice Kennedy joined, also accepts this holding. Simmons, 114 S. Ct. at 2201.

Interestingly, Rudd's appellate brief states that his trial counsel virtually conceded that Rudd would be a danger in free society.

Rudd further asserts that his counsel's failure to present this mitigating evidence prevented appellate review of whether Article 37.071 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure was unconstitutional as applied to him.

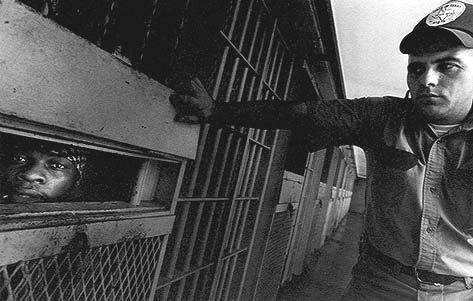

"Emerson Edward Rudd, J-23

wing, Maximum Segregation

cell block," from Ken Light's Texas Death Row

(1997).