(270 Ga. 688)

(512 SE2d 896)

(1999)

FLETCHER, Presiding Justice.

Murder. Fulton Superior Court. Before Judge Jenrette.

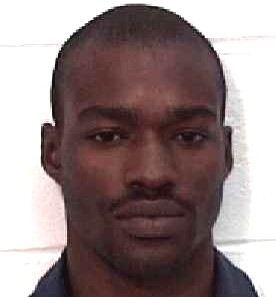

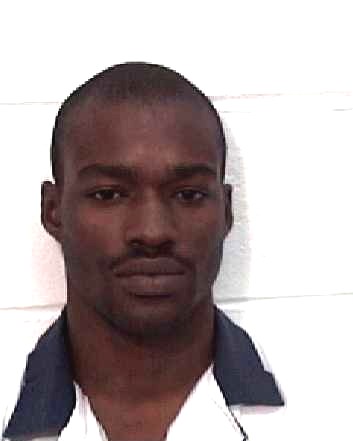

A jury convicted Norris Speed of malice murder in

the shooting death of Atlanta Police Officer Niles Johantgen, and

Speed was sentenced to death. 1 The

jury found as aggravating circumstances that the murder was

committed against a peace officer while engaged in the performance

of his official duties and that the murder was committed for the

purpose of avoiding, interfering with, or preventing a lawful arrest

of the defendant or another. Speed challenges the trial court's

in-camera conversation with a prospective juror, its evidentiary

ruling limiting the defense psychologist's testimony, and its

failure to give charge number 21.

We conclude that Speed waived his right to be

present during the in-camera questioning of the prospective juror

and did not object when the juror was excused for cause, the record

shows that the defense psychologist testified about the basis for

his opinion including the persons he interviewed and Speed's family

history, and the trial court was not required to give charge number

21 on when police may make a warrantless arrest.

Because none of the issues raised constitute

reversible error, we affirm.

SUFFICIENCY OF THE EVIDENCE

The evidence shows that Norris Speed was a drug

dealer who sold drugs in the Thomasville Heights area of Atlanta.

Officer Johantgen was a uniformed patrol officer whose regular beat

included the Thomasville Heights apartments.

On December 13, 1991, an Atlanta police

undercover officer arrested Jose Griffin, who worked for Speed,

after he had fled into Speed's grandmother's apartment. The police

confiscated $2,880 and 100 grams of cocaine during this arrest. The

police also noticed some marijuana on a table in the apartment, and

they returned with an arrest warrant for Speed's grandmother.

Although Officer Johantgen was not involved in

the undercover operation, he accompanied the other officers when

they served the warrant. Speed told his drug ring boss that he

believed the raid resulting in the loss of the drugs and money was "influenced

by" Officer Johantgen. He told another witness that he planned to

kill "the Russian" (Officer Johantgen's nickname).

On December 21, 1991, Officer Johantgen pulled

into the parking lot of the Thomasville Heights apartments, got out

of his car, and approached several men. He detained one of the men

and began to frisk him. Speed walked up behind Officer Johantgen and

shot him point-blank in the back of the head with a nine-millimeter

pistol, killing him instantly. Speed fired four more times at the

officer while he was on the ground, but all of these shots missed

and shattered on the pavement.

Speed then fled the scene in a car. At trial, one

witness testified that he saw Speed, who was well-known in the area,

walk up behind the officer and fire the fatal shot into his head.

Five more witnesses testified that they heard the first shot, looked

up, and saw Speed shooting at the officer on the ground.

After Speed fled, he met with his drug-ring boss

and told him that he had shot the Russian because Officer Johantgen

had threatened to "catch him dirty" and because the officer was

harassing people and searching them unnecessarily. Speed's

girlfriend heard him tell his drug boss that he shot the Russian.

Both Speed's drug boss and his girlfriend testified at trial. Speed

was arrested two days after the crime and he confessed that he shot

Officer Johantgen.

1. After reviewing the evidence in the light most

favorable to the jury's determination of guilt, we conclude that a

rational trier of fact could have found Speed guilty of malice

murder beyond a reasonable doubt. The evidence was also sufficient

to enable the jury to find the existence of the statutory

aggravating circumstances beyond a reasonable doubt.

2. Speed complains that the trial court

questioned a prospective juror on voir dire in camera without Speed

or his Counsel present. The prospective juror claimed that he could

not be impartial because he had overheard a conversation about the

case at his workplace, but the juror refused to divulge what he had

heard. Speed initially objected to the trial court questioning the

juror in camera without the parties but later agreed to the

procedure, saying "I'm not happy . . . but I would prefer that

procedure over not talking to him at all." Speed made no further

objection after the in-camera questioning was completed, and the

juror was excused for cause due to his inability to be impartial.

A defendant and his counsel have a constitutional

right to be present at every stage of the defendant's trial,

including voir dire. This right, however, may be waived by the

defendant personally, or by his counsel if done in the defendant's

presence. The record shows that Speed waived his right to be present

during the in-camera questioning of the prospective juror, and he

made no objection when the prospective juror was excused for cause.

Therefore, this issue is waived on appeal.

3. The trial court did not err by excusing for

cause four prospective jurors due to their inability to consider a

death sentence. The trial court also did not err by qualifying seven

prospective jurors who Speed claims would automatically vote for a

death sentence.

4. No prospective jurors were erroneously

qualified to serve due to their exposure to pretrial publicity; the

seven jurors about whom Speed specifically complains did not have

opinions so fixed and definite that they could not set them aside

and render a decision based solely on the evidence presented in

court. The trial court also did not err by denying Speed's motion

for a change of venue.

5. Prospective jurors Foley, Miller, Lindsey, and

Pittman were not erroneously qualified to serve for any reason

stated by Speed.

6. The trial court did not err by denying Speed's

Batson v. Kentucky motion. The reasons given by the state for the

exercise of its peremptory strikes were race-neutral and sufficient.

7. During voir dire, a prospective juror stated

that she believed that the justice system was biased against African-Americans

and that she has "an awareness" that the death penalty is sought

more for black defendants who kill white victims (Speed is African-American

and the victim was white). When the prosecutor asked her how

strongly she held this belief, Speed's counsel objected to this line

of questioning saying, in front of the juror, "It's a fact. [The

assistant district attorney] knows that his office seeks the death

penalty more often against black defendants." The trial court told

Speed's counsel that it was not the proper time to testify. Later,

the state moved to excuse this prospective juror for cause based on

defense counsel's comment, and the trial court excused her. We find

no error. "The single purpose for voir dire is the ascertainment of

the impartiality of jurors, their ability to treat the cause on the

merits with objectivity and freedom from bias and prior inclination.

The control of the pursuit of such determination is within the sound

legal discretion of the trial court, and only in the event of

manifest abuse will it be upset upon review." We conclude that the

trial court did not abuse its discretion in excusing this

prospective juror for cause due to bias resulting from defense

counsel's comment.

8. It was not improper for the state to introduce

evidence of Speed's drug dealing and to refer to Speed as a drug

dealer. Speed's drug dealing was relevant to his motive for the

murder, and relevant evidence does not become inadmissible simply

because it incidentally places a defendant's character into

evidence.

10. Speed's arrest was lawful and his confession

was voluntary.

11. It is not error to allow the jury to have a

written transcript of tape-recorded evidence when a proper

foundation has been made. Although Speed complains that he was not

provided before trial with the transcript of the audiotape of the

police radio traffic at the time of Officer Johantgen's death, he

did not object to the use of the transcript at trial or argue that

any portion of the transcript differed from the audiotape. The jury

was also instructed that the transcript was not evidence. Therefore,

this contention is without merit.

12. The trial court did not err by denying

Speed's motion for mistrial because there was insufficient evidence

that the state had violated the trial court's gag order.

13. Speed did not object when the victim's widow

identified the victim in a photograph taken when he was alive, but

did object that the photograph was irrelevant and inflammatory when

it was later admitted into evidence. Under these circumstances, we

find no error.

14. The trial court did not abuse its discretion

in admitting preautopsy photographs of the deceased victim. The

admission of crime scene photographs was also not error.

15. The trial court did not abuse its discretion

by allowing the state to use a mannequin dressed in the victim's

jacket as a demonstrative tool during the questioning of the medical

examiner. The medical examiner used the mannequin to illustrate for

the jury how bullet-fragment damage to the victim's body and jacket

was consistent with the crime scene evidence.

16. Speed was not harmed by the admission of

Officer Johantgen's death certificate.

17. The trial court did not abuse its discretion

in qualifying the medical examiner as an expert witness in injury

causation and interpretation. It was also not error to qualify the

state firearms expert as an expert in crime scene reconstruction.

18. The trial court did not abuse its discretion

in allowing certain questions to be asked on the redirect

examination of witness Johnny Roberts.

19. The trial court did not improperly restrict

the cross-examination of witness James Sims.

20. The trial court did not err in ruling that

the state could impeach state witness Patrick Norman with a prior

inconsistent statement and allowing the prior statement to be

admitted into evidence.

21. The state did not improperly question state

witness Christine Bibbs about a prior inconsistent statement that

she made to police.

22. During the direct examination of Dwayne

Gatlin, the state elicited that he had previously been convicted of

forgery and mail theft. On cross-examination, Speed began to

question Gatlin about the facts and circumstances behind these

convictions, but the trial court sustained a state objection that

the proper method of impeachment was through certified copies of the

convictions. Although a party generally must prove a prior

conviction by introducing a certified copy of the conviction, this

requirement may be waived. In this case, the prosecutor waived the

best evidence objection by eliciting on direct examination the

witness's testimony about his prior convictions, and the trial court

erred in sustaining the state's objection. This error was harmless,

however, because the witness admitted his convictions and offered no

favorable explanation for them and there was overwhelming evidence

of the defendant's guilt.

23. The trial court did not abuse its discretion

in allowing certain questions to be asked on the redirect

examination of witness Steve Burton.

24. Pretermitting the issue of admissibility,

Speed was not harmed by the introduction of an incriminating

statement that he made to his girlfriend while in jail because it

was cumulative of the overwhelming evidence of his guilt.

25. The trial court did not abuse its discretion

in limiting Speed's cross-examination of state witness Jeff Goodwin.

26. During the trial, a bailiff informed the

trial court that a juror had complained that Juror Washington

claimed that he knew the victim and would vote the opposite of the

other jurors. The trial court questioned Juror Washington, who

denied saying that he knew the victim or would vote the opposite of

the other jurors. The trial court then individually questioned the

other jurors. Six jurors stated that Juror Washington had either

claimed that he knew the victim or would vote the opposite of the

others. One juror stated that Juror Washington had said, "we all

know what we have to do," and another juror stated that Juror

Washington had been singing, "I know who's guilty." However, the

jurors other than Juror Washington denied discussing the outcome of

the case, and all stated that they would be fair and impartial.

Therefore, the trial court did not abuse its discretion in denying

Speed's motion for mistrial. The trial court also did not err by

excusing Juror Washington and replacing him with an alternate juror.

27. An assistant district attorney did not

violate Caldwell v. Mississippi by introducing one of her colleagues

during the opening statement in the guilt-innocence phase as an "appellate

lawyer in our office."

28. Speed was not harmed by the prosecutor's

introduction of the district attorney, who was seated at the

prosecution table, during the closing argument in the guilt-innocence

phase.

29. The state's closing argument in the guilt-innocence

phase was not improper.

30. Contrary to Speed's contention, the trial

court allowed Speed's psychologist to testify about the basis for

his opinion, and it only prevented Speed's expert from repeating

verbatim his conversations with Speed's family members and friends.

To show the basis for his opinion, the defense psychologist was

permitted to list the people he had interviewed about Speed's

background and to recite Speed's family history, including anecdotal

incidents from Speed's childhood. Thus, Speed's argument that the

state psychologist attacked the defense psychologist for lacking a

basis for his opinion, which Speed was allegedly unable to

introduce, is without merit. In fact, the record shows that the

state psychologist, who testified in rebuttal, commended the defense

psychologist on the thoroughness of his background investigation.

The state expert simply stated that he had not heard any testimony

from the defense psychologist, or read anything in his report, that

would support a diagnosis of dependent personality disorder. We find

no error.

31. Speed was not harmed by the failure of the

state psychologist, who did not examine the defendant, to reduce his

findings to writing and serve them on the defense before trial. The

record shows that the state psychologist was not contacted until the

trial had begun, and defense counsel was able to interview the state

psychologist before any psychological testimony was introduced by

either side.

32. OCGA 17-10-1.2

on victim-impact evidence is not unconstitutional, and it is not an

ex post facto law violation to apply this statute to a crime that

was committed before the statute was enacted. The only victim-impact

witness was Officer Johantgen's widow and her brief testimony was

not improper. Speed's trial occurred two months after OCGA

17-10-1.2 was enacted, and the

pretrial procedure and jury charge now used with victim-impact

evidence had not been formulated by this Court. Speed did not

request a jury charge on victim-impact evidence. We conclude that

Speed was not harmed by the lack of a pretrial hearing or a jury

charge on victim-impact evidence.

33. Speed complains that the state committed

prosecutorial misconduct by asking an improper question to witness

Major Taylor. The trial court, however, sustained Speed's objection

to the question and Speed did not request further action by the

trial court. After an objection to an improper question is sustained,

there is no reversible error absent a request from the complaining

party for additional corrective action.

34. Speed asked mitigation witness Reverend Butts

if he had observed the police treatment of other young black males

in the Thomasville Heights area. The state objected on relevancy

grounds, and the trial court sustained the objection. We find no

error. While the permissible scope of mitigation evidence is wide,

mitigation evidence must relate to the defendant's character or

background or circumstances of the offense on trial. The witness

testified that he had never observed any police interaction with

Speed, and evidence of how others may have been treated by the

police is irrelevant.

35. The state's cross-examination of Reverend

Butts was not improper.

36. The trial court did not abuse its discretion

in limiting Speed's cross-examination of the victim's police

supervisor.

37. A jailer who had observed Speed every day for

at least eight months testified as a mitigation witness and stated

that Speed was a quiet, compassionate inmate. On cross-examination,

the prosecutor, apparently anticipating the testimony of the defense

psychologist that Speed had a dependent personality disorder, asked

the jailer if Speed had a dependent or independent personality.

Speed objected that the jailer was not qualified to answer the

question, but the trial court overruled the objection. The jailer

answered that Speed had a strong, independent personality based on

his demeanor and character and that he did not seem to depend on any

jailer or inmate. The jailer also testified over objection that he

was surprised that the defense psychologist had diagnosed Speed with

a dependent personality disorder because Speed "hasn't exuded any of

those qualities." Although the jailer was not an expert, "after

narrating the facts and circumstances upon which his testimony is

based, a nonexpert witness may express his opinion as to the state

of mind or mental condition of another." We find no error.

38. Besides the jailer, Speed presented his

teacher at the jail, who also testified that Speed was a quiet,

nonviolent inmate who did not cause problems. The state presented

four rebuttal witnesses, all jailers, who testified about several

disruptive incidents, including a fight, that Speed had been

involved in awaiting trial. Speed complains that the state did not

provide notice of these witnesses under OCGA

17-10-2 (a), but Speed's cross-examination of the rebuttal

witnesses shows that his lawyer was aware of these witnesses and the

incidents about which they testified. Since the four witnesses were

presented as rebuttal witnesses, and Speed had some notice of their

testimony, we find no error.

39. The state's sentencing phase closing argument

was not improper.

40. The trial court did not err by sending a

written copy of the alleged statutory aggravating circumstances out

with the jury during its deliberations, as required by OCGA

17-10-30 (c).

41. The sentencing phase verdict form was not

error. The trial court properly declined to use Speed's requested

verdict form because it included the option of deadlock.

42. During the charge conference, the trial court

agreed to give Speed's penalty phase request to charge number 21,

which listed the circumstances under which the police can make a

warrantless arrest. Speed contended that the (b) (10) aggravating

circumstance did not apply because Officer Johantgen was not making

a lawful arrest. Instead, Speed argued that the officer was acting

outside the scope of his official duties when he detained and

frisked one of the men in the parking lot.

After closing arguments in the penalty phase, the

trial judge had to leave town due to a family member's serious

illness. The following day, a substitute judge gave the court's

charge to the jury and presided over the deliberations. After the

charge was completed, the substitute judge pointed out to the

parties that he had not given Speed's request to charge number 21

because the original trial judge had left word that he had not meant

to give that charge. Speed announced that he reserved all objections

to the charge for the motion for new trial.

On appeal, Speed complains that the failure of

the trial court to give the agreed charge was reversible error

because he made his argument anticipating that the charge would be

given and the failure to do so impaired his closing argument. We

disagree. First, the trial court was not required to give Speed's

request to charge number 21. The charge as given on the statutory

aggravating circumstances tracked the language of the recommended

charge in the pattern jury instructions, and we have never required

a trial court to go beyond the pattern charge. Second, if Speed was

misled about the charge during his closing argument, it was

incumbent upon him to request to reargue. His failure to do so

waives this issue on appeal. We further conclude that Speed can show

no harm resulting from the substitution of the trial judges.

43. The trial court's guilt-innocence phase jury

charge was not improper. Speed claims that the trial court erred by

refusing to give several of his requested charges, but they were

either already covered by the charge or not supported by the

evidence. The trial court correctly denied Speed's requested "two

theories" charge.

44. The trial court's penalty phase charge on the

two statutory aggravating circumstances was not improper.

45. The trial court's sentencing phase jury

charge was not improper. Speed's requests to charge that the trial

court denied were either already covered by the charge or were

inaccurate statements of the law. The trial court is not required in

its charge to identify or enumerate mitigating circumstances for the

jury, nor is the trial court required to charge the jury on the

consequences of a deadlock.

46. The trial court did not err in failing to

charge the jury in the sentencing phase on a burden of proof for

non-statutory aggravating circumstances.

47. The indictment was valid.

48. OCGA 16-5-1,

the murder statute, and 17-10-30,

which authorizes a death sentence for murder, are not

unconstitutional.

49. Because Speed failed to prove purposeful

racial discrimination in the state's intent to seek the death

penalty in his case, the trial court did not err by denying his

motion to preclude the state from seeking the death penalty.

50. Speed's equal protection claim regarding the

race and gender of the Fulton County grand jury foreperson is

without merit. The record shows that the Fulton County grand jury

elects its foreperson without input or assistance from the state.

51. The trial court did not err in its rulings on

Speed's discovery motions.

52. The trial court did not err by granting the

state's motion in limine, which prevented Speed from referring to "unrelated

homicides" without first showing that these homicides were relevant

to Speed's case.

53. Speed complains that Brady v. Maryland was

violated because the trial court permitted the state to withhold

favorable evidence during discovery. More than a year after Officer

Johantgen's murder, several Atlanta area police officers, including

two officers who worked in the same zone as Officer Johantgen, were

arrested for committing crimes such as burglary and armed robbery.

Speed sought the personnel and investigative files of these officers,

speculating that Officer Johantgen may have been involved in the

crime ring and therefore may not have been acting in the performance

of his official duties when he was murdered. Speed, however, fails

to show that there was any link between the information sought and

the circumstances of Officer Johantgen's murder or that the state

withheld any exculpatory or favorable evidence. We therefore

conclude that this enumeration is without merit.

54. The trial court did not err by denying

Speed's motion for recusal of the trial judge due mainly to the

judge's previous employment as an Atlanta police officer,

investigator for the district attorney's office, and assistant

district attorney. The trial court correctly determined, pursuant to

Uniform Superior Court Rule 25, that a reasonable person would not

conclude, assuming the truth of all alleged facts, that the judge

harbored a bias stemming from an extrajudicial source, which is of

such a nature and intensity that it would impede the exercise of

impartial judgment.

55. Shortly after the conclusion of Speed's trial,

the trial judge's law clerk learned of a vacancy in the criminal

division of the Attorney General's office. The law clerk applied for

the position and submitted several criminal law writing samples,

including memoranda drafted to assist the trial judge during Speed's

trial. The trial judge was not aware that his law clerk had applied

for this position. When the assistant attorney general responsible

for hiring realized that some of the writing samples involved an on-going

capital case in which the Attorney General would represent the state

on appeal, she informed the parties and the trial judge of what had

occurred, returned the writing samples, and insulated the rest of

the criminal division from exposure to them. The law clerk withdrew

his application with the Attorney General's office, and the trial

judge ended the law clerk's assistance with Speed's case. Speed

subsequently filed a motion to recuse the trial judge from further

participation in the post-trial proceedings and moved for a mistrial

on this ground.

An independent judge presided over a hearing on

this issue. He determined, after reading the writing samples and

hearing testimony from the trial judge and the law clerk, that the

memoranda contain "little or no original comment from the law clerk"

and consist mostly of down-loaded verbatim material from the Michie

Company's "Georgia Law on Disk," available to any legal researcher.

He concluded that the state gained no advantage from the disclosure

of the memoranda and that no reasonable person would find an

appearance of impropriety warranting the recusal of the trial judge.

Upon review of the record, we agree.

56. Speed's death sentence was not imposed as the

result of impermissible passion, prejudice, or other arbitrary

factor. The death sentence is also not excessive or disproportionate

to the penalty imposed in similar cases, considering both the crime

and the defendant. The similar cases listed in the appendix support

the imposition of the death penalty in this case, in that all

involve the deliberate killing of a police officer in the

performance of his official duties, and thus show the willingness of

juries to impose the death penalty under these circumstances.

Paul L. Howard, District Attorney, Bettieanne C.

Hart, Peggy A. Katz, David E. Langford, Assistant District Attorneys,

Thurbert E. Baker, Attorney General, Susan V. Boleyn, Senior

Assistant Attorney General, Paige Reese Whitaker, Assistant Attorney

General, for appellee.

Notes

1 The crime

occurred on December 21, 1991. The grand jury indicted Speed for

malice murder on January 28, 1992, and the state filed a notice of

intent to seek the death penalty on February 10, 1992. The trial

took place from September 7 to October 1, 1993. The jury convicted

Speed of malice murder on September 27, 1993, and recommended a

death sentence on October 1, 1993. Speed filed a motion for new

trial on October 11, 1993, which was amended on October 25, 1993,

and further amended on March 20, 1995, and May 25, 1995. The trial

court denied the motion for new trial on March 24, 1998. Speed filed

his notice of appeal on April 20, 1998, and this case was docketed

on May 20, 1998. The case was orally argued on September 14, 1998.

Michael Mears, James C. Bonner, Jr., for

appellant.