Opinion

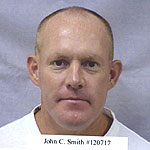

Appellant, John Clayton Smith, was convicted of two counts of murder in the first degree in violation of section 565.020.1, RSMo 1994, and two counts of armed criminal action in violation of section 571.015, RSMo 1994. Appellant was sentenced to death on each count of first degree murder and to consecutive twenty-year terms on the armed criminal action counts. Appellant appeals his convictions and sentences. Affirmed.

Viewed in the light most favorable to the verdict, State v. Barton, 998 S.W.2d 19, 21 (Mo. banc 1999), the facts are as follows.

Appellant began dating Brandie Kearnes, one of the two victims in this case, in 1995. At that time, Brandie lived near Canton with her mother, Yvonne Kurz, and her step-father, Wayne Hoewing, the other victim.

While they were dating, Brandie and appellant made plans to live together. Appellant borrowed $30,000 to buy a house for himself and Brandie. Around June 1, 1997, however, Brandie terminated the relationship with appellant, after which she chose to continue living with Yvonne Kurz and Wayne Hoewing.

Later that month, appellant contacted his former wife, Mary Smith, about visiting his children. Appellant had not visited his children for a year and a half prior to that time. Appellant visited with his children several times during June, once giving Smith some savings bonds and coin collections that he wanted the children to have.

At about 7:30 a.m. on the morning of July 4, 1997, appellant drove by O.C.'s Tavern in Canton and looked at Kearnes's car, which had been parked in the lot next to the tavern since the night before. Approximately fifteen minutes later, appellant telephoned Smith and asked what she planned to do with the children that day. Appellant was upset.

When Smith asked why, appellant replied, "Everything." When Smith asked appellant if he was having difficulties with Brandie, he said, "Just everything. I can't talk about it now. I gotta go," and hung up. Sometime later during the same morning, appellant telephoned Yvonne Kurz and asked whether Brandie had come home the night before. Kurz responded that Brandie had not come home. Appellant then asked, "She is seeing someone else, isn't she?"

Later that afternoon, appellant, after seeing Brandie driving on the highway, followed her to Brian Brooks's house and pulled up behind her in the driveway. Brandie got out of her car and spoke to appellant for about three minutes. Appellant then left.

At 11:05 p.m., appellant purchased a twelve-pack of beer at a convenience store in Canton. The store clerk noticed that appellant was preoccupied and appeared to be in a "weird mood."

Appellant left the convenience store and, sometime after 1:48 a.m. on July 5, 1997, drove to the residence where Brandie Kearnes and Wayne Hoewing resided. Appellant parked his truck approximately thirty yards from the residence. Taking some of the beers with him, but not any of the three guns he had in the truck, appellant walked around a large pond on the property and approached the residence.

Appellant entered the residence through the basement door, took off his shoes, and went upstairs.

Appellant located Kearnes and began to scuffle with her in the living room and kitchen area of the house. Appellant stabbed or cut Brandie eight times during the scuffle. The wounds did not immediately cause Brandie's death; she had time to write "It was Joh-" "I Y Tatu-" and "--andi s-v- T-tum" on the kitchen floor with her own blood. The last two messages referred to Tatum, Brandie's infant daughter, who was found unharmed at the feet of Brandie's body.

Appellant then entered the Hoewing's bedroom and attacked Wayne, who had been awakened by the sounds of scuffling coming from the living room. Appellant got on top of Wayne on the bed and began stabbing him, inflicting eleven stab or cut wounds.

Yvonne Kurz attempted to push appellant off Wayne, but appellant slashed her arm. She retreated into the bathroom and closed the door. While appellant was at the door of the bedroom, Wayne was able to gain possession of a loaded gun he kept in the house. Appellant, seeing the gun, said, "Shoot me. Go ahead and shoot me." No shots were fired, however, and appellant left the bedroom. Kurz was eventually able to call for help from the bathroom.

Appellant then went back downstairs and left the house through the basement door after putting on his shoes. Appellant walked from the Hoewing residence to the nearby farm of Bill Lloyd, where he hid his knife under some tin and attempted to steal a tractor.

After crashing the tractor into a flatbed trailer on the property, appellant fled on foot. He eventually traveled to another nearby residence, where he stole a truck and drove away. Soon thereafter appellant was apprehended after crashing the truck.

When medical personnel reached the Hoewing residence, Brandie was already dead. She had been partially stripped of her clothing. She was lying face up on the kitchen floor. Eight cut or stab wounds had been inflicted on her neck, chest, abdomen, arm, and thigh. The stab wounds to the chest punctured Brandie's lung, and the wounds to her abdomen cut her liver and one kidney.

The medical personnel treated Wayne Hoewing briefly, but soon pronounced him dead. He received eleven cut or stab wounds to the chest, arms, leg, hand, and hip. He bled to death from those wounds.

Police found several pieces of evidence at the scene of the crime. Police noticed a trail of blood left by appellant as he left the house. One of appellant's socks was recovered from under the body of Wayne Hoewing. Police found three beer cans outside of the residence and also found the keys used by appellant to break into the house.

After being apprised several days after the murders of the messages written with blood on the kitchen floor, police seized the linoleum bearing those messages. The police did not find any weapons. Later in July, however, a worker at the farm where appellant had attempted to steal the tractor found a knife hidden under some tin. The original owner of the knife identified it as the knife she had given to appellant.

At trial, appellant did not contest his identity as the killer, but he offered the testimony of Dr. Michael Stacy, who testified that appellant's capacity to deliberate before the killings was substantially impaired. The state offered expert testimony to rebut Dr. Stacy's diagnosis and findings. The jury found appellant guilty on both counts of murder in the first degree and both counts of armed criminal action.

During the penalty phase of the trial, the state introduced evidence of appellant's prior violent history with women, appellant's prior convictions for felony stealing and violating an order of protection, and the impact that the murders had on the victims' families. Appellant presented the testimony of friends and family and the testimony of a mental health professional in mitigation of punishment.

After the close of the penalty phase evidence and after the instructions and arguments of counsel, the jury found the following aggravating circumstances with regard to Brandie Kearnes: that the murder of Brandie Kearnes was committed while appellant was engaged in the commission of another unlawful homicide and that her murder was committed while appellant was engaged in the perpetration of a burglary.

With respect to Wayne Hoewing, the jury found that the same aggravating circumstances applied. The jury also found that Wayne's murder involved depravity of mind in that the murder was wantonly vile, horrible, and inhuman. The jury recommended a sentence of death on each count of murder in the first degree.

On July 6, 1999, the trial court imposed sentence in accordance with the recommendation of the jury. In addition, the court sentenced appellant to consecutive terms of twenty years in the department of corrections on the armed criminal action counts. This appeal followed.

I.

Appellant claims that the trial court abused its discretion when it overruled his motion to disqualify the Lewis County prosecuting attorney, thereby violating his rights to due process, to a fair trial, and to be free from cruel and unusual punishment. U.S. Const. amend. V, VI, VIII, and XIV; Mo. Const. art. I, secs. 10, 18(a), and 21.(FN1)

The record reflects that before prosecuting appellant for first degree murder, the prosecutor twice acted as appellant's defense counsel. On April 28, 1981, sixteen years before appellant was charged in the instant case, the prosecutor entered an appearance as appellant's attorney on a work permit revocation matter. Appellant's work permit was revoked on that same date. At a hearing concerning whether the prosecutor should be disqualified from prosecuting appellant in the present case, the prosecutor testified that he had no recollection of the work permit representation.

In 1983, fourteen years prior to charging appellant in the instant case, the prosecutor represented appellant on a felony stealing charge. Pursuant to sentencing on the felony stealing charge, the court in that case ordered a presentence investigation report to be made. At the hearing on appellant's motion to disqualify, the prosecutor testified that he remembered having represented appellant in 1983, but that he did not recall anything about the facts of that case.

Evidence touching upon both cases in which the prosecutor defended appellant was admitted during appellant's trial in the instant case. The motion to revoke appellant's work release permit in 1981 was filed following two confrontations between appellant and Muriam Daniels, appellant's former girlfriend. Daniels testified during the penalty phase of appellant's trial for murder. She stated that appellant had twice pulled her out of cars, once after breaking through the car's window with his fist. She described an incident in which appellant came into her school and threw her up against some lockers.

Daniels testified that appellant "ended up having a restraining order placed on him." The state used the 1983 felony stealing conviction to prove appellant's status as a prior offender and introduced it during the penalty phase of the trial in support of proof of an aggravating circumstance.

Rule 4-1.9 governs the disposition of appellant's claim of conflict. The rule reads:

A lawyer who has formerly represented a client in a matter shall not thereafter:

(a) represent another person in the same or a substantially related matter in which that person's interests are materially adverse to the interests of the former client unless the former client consents after consultation; or

(b) use information relating to the representation to the disadvantage of the former client except as Rule 1.6 would permit with respect to a client or when the information has become generally known.

With respect to subsection (a), there is no question that the prosecutor representing the state in this case, by prosecuting appellant and by seeking the penalty of death, was acting adversely to appellant's interests. There is also no question that appellant did not consent to the prosecutor's involvement on behalf of the state. The only question to be determined, therefore, is whether the earlier cases in which the prosecutor defended appellant are substantially related to the instant case.

Appellant speculates that the prosecution knew of the events involving Muriam Daniels and that his knowledge was, at least, a factor in his decision to seek the death penalty. As appellant eventually concedes, he does not meet his burden under the rule.

The prosecutor's connection to the work permit revocation proceeding in 1981 amounted to a single appearance made on the day on which the trial court ordered the permit revoked. This connection is de minimis. As for the felony stealing conviction in 1983, although the prosecutor likely had privileged communications with appellant prior to entering his guilty plea, the record does not provide support for appellant's assumption that the prosecutor was engaged in any communication with appellant that had any relevance whatsoever to the later murders of the victims in this case.

Nor does the record provide support for appellant's assumption that the prosecutor sought the death penalty because of any other information he gleaned in the course of representing appellant. Appellant's conviction was used in the present case only to prove that he was a prior offender. Appellant's conviction was a matter of public record, available to any prosecutor. The prosecutor need not be disqualified simply for entering the felony stealing conviction into evidence. State v. Clark, 913 S.W.2d 399, 403-04 (Mo. App. 1996); Rule 4-1.9(b). Appellant has made no showing that the matters are substantially related.

Appellant cites only one case in which the court discusses the facts of the case with an eye toward determining whether the various representations are substantially related. In Wilkins v. Bowersox, 933 F. Supp. 1496 (W.D. Mo. 1996), petitioner Wilkins argued that his right to due process of law had been violated because the prosecuting attorney in his first degree murder case had represented him in a juvenile case approximately six years before and failed to disclose that fact to the trial court or to defense counsel. The state sought the death penalty.

The district court stated that "[t]he threshold question...is whether the prosecution for the murder...had a substantial relationship to the juvenile court matter in 1979" and that "[w]hether there is a 'substantial relationship' involves a full consideration of the facts and circumstances in each case." Wilkins, 933 F. Supp. at 1522-23.

The court found that Wilkin's mental health was central to both the juvenile proceeding and the charge of first degree murder and that the two representations were, therefore, substantially related. Id. at 1523. The court then issued a writ of habeas corpus in favor of Wilkins, stating that "the entire conduct of the criminal proceeding was obviously affected by the conflict of interest caused by the prosecutor's prior representation and his nondisclosure." Id. at 1524.

Wilkins is distinguishable on its facts. The relationship between the prosecutor's earlier representations of appellant and his later prosecution of him in this case is not so substantial as the relationship between the two representations at issue in Wilkins. In this case there is no central issue, such as mental health in Wilkins, common to the work permit revocation proceeding, the felony stealing conviction, and the charge of murder in the first degree.

For the same reason, State v. Ross, 829 S.W.2d 948 (Mo. banc 1992), does not support appellant's claims. In that case, which was decided in light of Rules 4-1.7 and 4-1.11, a lawyer who served as a part-time assistant prosecuting attorney represented the defendant in a civil case arising out of the same facts for which defendant had been charged by another lawyer who was a member of the same firm as the first lawyer. Measuring that circumstance by the language in Rule 4-1.9, it is clear that in Ross there was a substantial relationship between the civil and criminal cases, namely, the very same set of facts. Nothing approaching that relationship exists in the instant case.

Despite his assertion on the one hand that the matters in 1981 and 1983 are substantially related to his present case, appellant also explicitly concedes in both his original and reply briefs that if he faced any punishment but death he would not question the prosecutor's ability to prosecute him. In effect, therefore, he concedes that he does not meet his burden under Rule 4-1.9.

Appellant argues that in all death penalty cases the defendant should benefit from an irrebutable presumption that privileged information was obtained by the prosecuting attorney when he was defendant's counsel and is being used to the accused's disadvantage.

Appellant cites two cases in support of his argument that death penalty cases are different. In Reaves v. State, 574 So.2d 105 (Fla. 1991), the Supreme Court of Florida said, "Under this decision, a conviction must be reversed if the trial court denies a pretrial defense motion to disqualify a prosecutor who previously has defended the defendant in any criminal matter that involved or likely involved confidential communications with the same client." Reaves, 574 So.2d at 107. Similarly, in State v. Stenger, 760 P.2d 357 (Wash. 1988), the Supreme Court of Washington held that a prosecutor who had defended Stenger on two criminal charges ten years before seeking to levy the death penalty on him should have been disqualified.

The court noted that the prosecutor would not normally be disqualified in these circumstances, since the charge of aggravated murder in the first degree was "unrelated to the accused's previous crimes concerning which the prosecuting attorney represented him." Stenger, 760 P.2d at 360. The court went on to say, however, that the potential imposition of the death penalty changed the analysis:

The factual information the prosecuting attorney obtained from the accused by virtue of the prosecuting attorney's previous legal representation of the accused, including information about the defendant's background and earlier criminal and antisocial conduct, is information closely interwoven with the prosecuting attorney's exercise of discretion in seeking the death penalty in the present case.

Id. The court ordered the disqualification of the prosecuting attorney.

This Court is not persuaded that it should abandon Rule 4-1.9, under which the various representations that allegedly result in a conflict of interest must be connected by something substantially more than the prosecutor himself if they are to be substantially related. A focused approach, where the court examines the relevant facts of the case in order to determine whether the various matters are substantially related, is preferable.

This Court will continue to follow its rule without engrafting upon it an exception for first degree murder cases in which the penalty of death is sought. Under this approach, as discussed above, the trial court's decision not to disqualify the prosecutor was not an abuse of discretion.

II.

Appellant contends that the trial court erred when it sustained the state's challenge for cause to venirepersons Fox, Douglas, and Deihl. Appellant alleges that the state is not entitled to strike a juror for the sole reason that the juror, acting as the foreperson, cannot sign the verdict assessing the penalty of death.

Venirepersons may be excluded from the jury when their views would prevent or substantially impair the performance of their duties as jurors in accordance with the court's instructions and their oaths. Wainwright v. Witt, 469 U.S. 412, 424 (1985); State v. Rousan, 961 S.W.2d 831, 839 (Mo. banc 1998).

A challenge for cause will be sustained if it appears that the venireperson cannot "consider the entire range of punishment, apply the proper burden of proof, or otherwise follow the court's instructions in a first degree murder case." Rousan, 961 S.W.2d at 839. The trial court is in the best position to evaluate a venireperson's commitment to follow the law and is vested with broad discretion in determining the qualifications of prospective jurors. Id.

The trial court's "ruling on a challenge for cause will not be disturbed on appeal unless it is clearly against the evidence and constitutes a clear abuse of discretion." State v. Kreutzer, 928 S.W.2d 854, 866 (Mo. banc 1996). "A juror's equivocation about his ability to follow the law in a capital case together with an equivocal statement that he could not sign a verdict of death can provide a basis for the trial court to exclude the venireperson from the jury." Rousan, 961 S.W.2d at 840; see also State v. Clayton, 995 S.W.2d 468, 476 (Mo. banc 1999).

a. Venireperson Fox

During the state's voir dire, Fox repeatedly stated that she would find it "hard" to sentence someone to death. She thought she "probably" could impose the death penalty if the crime was "atrocious enough." She stated that she would not expect the state to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. When asked whether she could fill out and sign a verdict form sentencing the defendant to death, Fox unambiguously answered that she could not.

The trial court, after taking into consideration Fox's "demeanor and...responses," decided that her ability to consider the full range of punishment was impaired. Considering Fox's qualified answers concerning her ability to impose the death penalty after having been convinced beyond a reasonable doubt of the appellant's guilt and her unequivocal statement that she could not sign a verdict form assessing the penalty of death, the court did not abuse its discretion in so deciding.

b. Venireperson Douglas

In response to the state's questions during voir dire, Douglas stated that she could "go for" the death penalty. Without qualification, she said that she could decide whether the state met its burden of proof, whether aggravating circumstances existed beyond a reasonable doubt, whether mitigating factors outweighed aggravating factors, and whether the death penalty was appropriate. When asked whether she could sign a verdict form while acting as the foreperson of the jury, however, Douglas replied that she did not know whether she could. Douglas said that when it came to signing the paper, she would feel as if she were "committing murder, too."

Venireperson Douglas, unlike venireperson Fox, did not equivocate when asked whether she could impose the sentence of death. The trial court did not, however, abuse its discretion when it disqualified Douglas. It is true that "[a] juror's equivocation about his ability to follow the law in a capital case together with an unequivocal statement that he could not sign a verdict of death can provide a basis for the trial court to exclude the venireperson from the jury." Rousan, 961 S.W.2d at 840; see also Kreutzer, 928 S.W.2d at 866-67.

It does not follow, however, as appellant insists, that both equivocation and an unequivocal statement about being able to sign the death verdict are required before the trial court may disqualify a venireperson. An unequivocal statement concerning a venireperson's inability to sign a death verdict alone is enough. State v. Johnson, 968 S.W.2d 686, 694 (Mo. banc 1998).

An uncompromising statement by a juror that he or she refuses to sign a death warrant hints at an uncertainty underlying the juror's determination to consider the full range of punishment. No panel of twelve jurors, all of whom decided that he or she could not sign a verdict form assessing the death penalty against the defendant, could be said to have the unimpaired ability to consider the appropriateness of the death penalty. The trial court, therefore, did not run afoul of the rule that "the exclusion of venire members must be limited to...those whose views would prevent them from making an impartial decision on the question of guilt." Gray v. Mississippi, 481 U.S. 648, 657-58 (1986) (citing Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1967)).

c. Venireperson Deihl

In response to questioning by the state during voir dire, Deihl opined that it would be hard to sentence a person to death. When asked by the state whether he could realistically consider assessing the death penalty once the state met its burden of proof, Deihl answered "Yes." When asked whether he could sign a verdict form assessing the death penalty, he answered "No." The trial court did not abuse its discretion when it decided to disqualify Deihl on the basis of his unqualified statement that he could not sign a verdict form assessing the penalty at death.

III.

Also in connection with voir dire, appellant claims that the trial court abused its discretion when it sustained an objection by the state to defense counsel's statements concerning the meaning of "life without parole." Defense counsel said to one of the voir dire panels, "[T]hese terms mean exactly what they say. The death penalty means what it says. Life without parole means life without...." At this point the state objected, and the trial court sustained the objection.

Defense counsel continued, "[t]he terms in the instruction mean exactly what they say," at which time the state again objected. The trial court again sustained the objection. Two persons from the voir dire panel served on the jury. Appellant now contends that the trial court's action "confirmed" the jurors' misunderstanding of the law, encouraging them to fear that "life without parole" meant anything but life without parole.

Appellant's argument is without merit. The trial court repeatedly instructed the jury that one of the sentencing options was "imprisonment for life by the Department of Corrections without eligibility for probation or parole." The meaning of the words "without eligibility for probation or parole" is clear. State v. Feltrop, 803 S.W.2d 1, 14 (Mo. banc), cert. denied, 501 U.S. 1262 (1991). Even if it were not clear from the plain language of the instructions that life without parole means just that, defense counsel dispelled any possible ambiguity during appellant's penalty phase closing argument:

[L]ife imprisonment without parole is a harsh punishment.... Think about the nature of that punishment, never ever to be free again, never to make a meaningful decision on your own again, never to have your children or your loved ones see you free again, no graduation ceremonies, no marriages, no confirmations, no more of the happy times out free.... No chance of parole ever.... If you sentence him to life without parole he will be guarded by prison guards that haven't even been born yet, if he lives that long. If you sentence him to life without parole, he is returning to a prison cell everyday for the rest of his life.

(emphasis added). The trial court did not abuse its discretion. This point is denied.(FN2)

IV.

Appellant argues that the trial court abused its discretion when it admitted into evidence a piece of linoleum on which Brandie Kearnes had written messages with her own blood shortly before she died, photographs of the linoleum, and testimony concerning that linoleum. Appellant contends that the messages written on the linoleum were largely irrelevant to any issue in the case and, in addition, aroused fear and prejudice in the minds of the jury that outweighed any possible relevance.

One or two days after police investigators processed the murder scene, relatives of victim Wayne Hoewing found writing on the linoleum of the kitchen floor near where Brandie Kearnes had died. The writing read "It was Joh-" and "I YTatu-."

The police processed and seized the linoleum several days after it was found by Hoewing's relatives. The police had not noticed the writing when the murder scene was first processed, apparently because the writing blended into the other blood patterns on the floor, but a videotape taken during the initial police processing showed that the writing was present on the floor at that time.

"The test for relevancy is whether the offered evidence tends to prove or disprove a fact in issue or corroborates other relevant evidence." State v. Rousan, 961 S.W.2d 831, 848 (Mo. banc 1998). Evidence that is logically relevant need not always be admitted, however.

If proffered evidence causes "prejudice wholly disproportionate to the value and usefulness of the offered evidence, it should be excluded." Id. The state, because it must shoulder the burden of proving the defendant's guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, should not be unduly limited in its quantum of proof. State v. Griffin, 756 S.W.2d 475, 483 (Mo. banc 1988). A trial court's ruling concerning whether the probity of offered evidence is outweighed by its prejudicial effect will not be disturbed absent an abuse of discretion. Rousan, 961 S.W.2d at 848.

A. "It was Joh-"

Appellant concedes that the message "It was Joh-" is logically relevant because it identifies appellant as the person who attacked Brandie Kearnes. Appellant contends, nevertheless, that the linoleum bearing the message should not have been admitted because appellant admitted that he was the person who attacked Brandie Kearnes, thereby making it unnecessary to produce evidence of the attacker's identity. The message, in appellant's view, became more prejudicial than probative once appellant admitted to being Brandie Kearnes's and Wayne Hoewing's killer.

Appellant's argument is not persuasive. The state must prove all of the elements of the crime beyond a reasonable doubt. The prosecution could not be certain that appellant would admit that he was the person who attacked Brandie once the defense began to present its case. Defense counsel reserved its opening argument, and although appellant argues that his defense was clear from witness endorsements and a doctor's reports presented to the prosecution before trial, it remains the state's burden "to establish all essential elements of a crime without relying on a defendant's extrajudicial admissions, statements or confessions." City of Albany v. Crawford, 979 S.W.2d 574, 575 (Mo. App. 1998).

Although the fact that the message was written in blood makes the evidence potentially more prejudicial than other, less graphic evidence, defendants are not prejudiced by the fact that graphic evidence is a consequence of brutal actions. Feltrop, 803 S.W.2d at 11. The evidence was more probative than prejudicial. The trial court did not abuse its discretion when it admitted it.

Appellant cites several cases for the proposition that, because appellant perhaps planned to admit his identity when the defense submitted its case, introduction of the written messages was not strictly necessary. These cases are distinguishable. Three of these cases involved the introduction of "other crimes" evidence. State v. Conley, 873 S.W.2d 233 (Mo. banc 1994); State v. Bernard, 849 S.W.2d 10 (Mo. banc 1993); State v. Collins, 669 S.W.2d 933 (Mo. banc 1994).

In cases involving evidence of other crimes, there is a danger that the jury will take into account the defendant's propensity to commit crime, a characteristic that is not strictly relevant to any fact in issue. Bernard, 849 S.W.2d at 17. There was no such danger presented in this case, where the evidence was introduced to show that appellant was in fact the killer. It cannot, therefore, be said that the messages written on the linoleum were so prejudicial that the trial court should have excluded them. Appellant also cites State v. Revelle, 957 S.W.2d 428 (Mo. App. 1997).

Revelle stands for the proposition that hearsay is admissible when it relates to an issue in the case. There is no conflict between Revelle and this case. As has already been explained, the identity of the killer was an issue that the state needed to prove when the messages were offered into evidence. It was not, therefore, an abuse of discretion on the part of the trial court to admit them.

B. "I Y Tatu-" and "--andi s-v- T-tum"

Appellant contends that the "I Y Tatu-" and "--andi s-v- T-tum" messages were totally irrelevant to any issue in the case.

Appellant's argument is without merit. As discussed above, the state, to prove the identity of the killer, sought to introduce into evidence the linoleum bearing the messages. To do so, the state was obliged to lay a foundation for the evidence.

The writings suggest, by their mention of Tatum and their use of the personal pronoun "I," that Brandie Kearnes was the author. They are, therefore, probative on the issue of who wrote the messages.

In addition, the message "It was Joh-" on the linoluem was hearsay that could not have been admitted unless the state could prove that the messages were Brandie's dying declarations. To prove this, the state was required to demonstrate that the messages were written while Brandie believed that death was imminent and that she had no hope of recovery. State v. Liggins, 725 S.W.2d 75, 76 (Mo. App. 1987).

The state is allowed to demonstrate such a belief "by any means.... It is enough if, from all the circumstances, it satisfactorily appears that such was the condition of the declarant's mind at the time of the declarations." State v. Brandt, 467 S.W.2d 948, 952 (Mo. 1971) (quoting State v. Proctor, 269 S.W.2d 624, 625 (Mo. 1954)). Brandie Kearnes's expression of her love for her child is relevant to whether she believed that she was about to die.

The messages, furthermore, are more probative than prejudicial, although they are written with the blood of Brandie Kearnes. The trial court did not abuse its discretion when it admitted the "I Y Tatu-" and "--andi s-v- T-tum" messages.

C. The Photographs of the Linoleum, the Expert Testimony, and the Examination of the Evidence by the Jury

Appellant argues that the photographs of the messages written on the linoleum, one of which was taken from a crime scene video and the others of which were taken moments before the police removed the linoleum containing the writings from the floor, should not have been admitted into evidence.

As detailed above, it was not error to admit the messages. The photographs of the messages were introduced to prove that, although the messages on the linoleum were not found during the initial police investigation, the messages were present on the floor at that time. Had the state not introduced these photographs, the jury could well have concluded that the messages were written by someone other than Brandie Kearnes sometime after Brandie died.

The pictures, therefore, provided the necessary foundation for the introduction of the messages themselves. The admission of the pictures did not constitute an abuse of discretion.

Appellant also argues that the trial court should not have allowed the testimony of expert witness Don Lock, who testified that he had found three messages, "It was Joh-," "I Y Tatu-," and "--andi s-v- T-tum."

According to Lock, one message, "--andi s-v- T-tum," was visible only when seen with the aid of laser light. Appellant's argument is largely premised on his mistaken assertion that the messages were irrelevant to any issue in the case. As decided above, the messages were admissible. Lock testified, furthermore, that the messages were not written with an "assisted hand," thereby providing further proof that the messages were written by Brandie Kearnes. The expert's testimony was probative and not unduly prejudicial. The trial court did not err when it allowed Lock to testify.

Finally, appellant suggests that the trial court itself added to the prejudicial effect of the evidence by inviting the jurors to handle the linoleum. The record reflects that the trial court allowed jurors to pass by a table on which the linoleum bearing the messages laid. The court suggested that the jurors not handle the evidence, but cautioned them that they should wear gloves if they felt it was "absolutely necessary" to do so. This does not amount to an prejudicial implicit invitation on the part of the trial court. Compare People v. Blue, 724 N.E.2d 920 (Ill. 2000). Rather, the trial court seemed to be attempting to protect the jurors and the evidence from unnecessary contamination. The trial court did not commit error.

V.

Appellant maintains(FN3) that the state impermissibly attacked his character during the guilt phase using irrelevant evidence in contravention of the precept that "there must be no conduct by argument, or otherwise, the effect of which is to inflame the prejudices or excite the passions of the jury." State v. Tiedt, 206 S.W.2d 524, 526 (Mo. banc 1947). Specifically, appellant complains that the prosecutor should not have asked Mary Smith, appellant's former wife, about how much contact appellant had with his children during the one and a half years preceding Father's Day, 1997. Appellant suggests that whether he was a good or bad father was irrelevant to any issue in his case.

In the guilt phase, Mary Smith testified to the following events. In June of 1997, appellant telephoned Smith several times to inquire about visiting his children. Shortly thereafter, appellant visited his children a number of times. During one visit he left some savings bonds and coin sets with Smith and said that he wanted his children to have them. These visits were followed by more telephone calls during which appellant asked about his children. During a call that occurred one day before the killing of Brandie Kearnes and Wayne Hoewing, appellant seemed upset.

He stated that "[e]verything" was wrong. He hung up after Smith asked about Brandie. After Smith testified to these events, the prosecutor asked how often appellant had been in contact with his children prior to the June 1997 telephone calls and visits. Smith answered that appellant had not visited his children for one and a half years prior to June, 1997, and that during that time he had called the children approximately six times.

It is true that the prosecution may not attack the character of a criminal defendant unless the defendant first puts his character into issue. State v. Johnson, 496 S.W.2d 852, 857 (Mo. 1973). Contrary to appellant's argument, however, in this case the prosecution did not introduce Mary Smith's testimony in an effort to attack appellant's character.

It is apparent that the state, by eliciting testimony concerning the contrast between appellant's behavior toward his children during the period immediately preceding the killings with his behavior during the year and a half before the killings, was attempting to demonstrate deliberation by the appellant.

Appellant's distress about his relationship with Brandie Kearnes, evident in his behavior during the last telephone call to Smith, is also relevant to appellant's motive. Altogether, the record shows that the state was no more trying to prove that appellant was a bad father before June of 1997 than it was trying to prove he was a good father during June of 1997. The trial court did not err when it admitted Smith's testimony.

VI.

Appellant asserts that the trial court plainly erred and abused its discretion when it admitted testimony in the guilt phase from Dr. Michael Stacy that appellant had choked his former wife and testimony from Dr. Jerome Peters that appellant had once fought with a coworker.(FN4)

In appellant's estimation, this testimony was prejudicial evidence of uncharged crimes that was totally irrelevant to the issue of whether defendant deliberated about killing Brandie Kearnes and Wayne Hoewing.

At trial, appellant argued that on the night of the killings his ability to deliberate was substantially impaired by the existence of a mental disease or defect. Dr. Stacy, an expert witness for the defense, testified that appellant suffered from "Recurrent Major Depression and Personality Disorder (Not Otherwise Specified)." He testified that he had reviewed the records of two prior hospitalizations of appellant. During cross-examination by the state, the following exchange occurred without objection by appellant:

Q: You are aware and the records reflect the reasons why [appellant] checked himself into these units during that time, don't they?

A: Yes, I believe so.

Q: And, in fact, one of the precipitating factors and one of the reasons why he checked himself into the hospital at that time was that his ex-wife filed for divorce and got an ex parte against him for choking her; isn't that correct?

A: That's correct.

Q: And from 1991 when he was divorced through until 1997, there were no hospitalizations, were there?

A: No, there were not.

Q: Now, doctor, it is important that the information you rely on is accurate and truthful and complete, isn't it?

A: That is correct.

To rebut Dr. Stacy's testimony, the state called Dr. Peters as an expert witness. Dr. Peters testified that he believed that appellant was alcohol dependent and that he suffered from "narcissistic personality disorder with obsessive compulsive traits." When the state inquired as to how records of past relationships formed a basis for his diagnosis, Dr. Peters responded:

It showed again the pervasive pattern throughout his life of this type of behavior where the self-centered behavior, exploiting those about them, taking advantage of them; and also coupled with that is the feeling of entitlement, the display of a great deal of entitlement, the scheduling of things. With a narcissistic personality everything revolves around them, not that they involve [sic] around the universe. They see themselves as the center of the universe. They are very self-centered and with that comes the behavior of an overwhelming arrogance, a condescension towards those about them. This is evidence by some of his behaviors in his employment records, that he exploited some workers, he displayed an arrogant behavior towards them and at times ended up in violence.

After the prosecutor asked for a concrete example and a defense objection was overruled, Dr. Peters continued:

One

episode is where he is

standing in line to unload a

truck and one person was

taking a little bit too

long. He ended up in

physical violence towards

that person. A lot of this

goes to how the narcissistic

personality sees things that

occur and it is never his

fault. It is always someone

else's fault. So, early on

in development they blame

others for what happens.

They can never really blame

themselves because this is

their personality, this is

how they do things. Thus,

everything that isn't right

has got to be someone else's

fault. That is what occurred

on the one episode when he

assaulted a fellow truck

driver.

The record also reflects

that before both doctors'

testimony, the court

instructed that jury that

[I]n the course of his testimony, [the doctor] may testify to statements and information that were received by him during or in connection with his inquiry into the mental condition of the defendant. In that connection, the Court instructs you that under no circumstances should you consider that testimony as evidence that the defendant did or did not commit the acts charged against him.

This Court is mindful of the fact that "evidence of prior uncharged misconduct is not admissible for the purpose of showing the propensity of the defendant to commit such crimes." State v. Burns, 978 S.W.2d 759, 761 (Mo. banc 1998). It is also well established, however, "that an expert witness may be cross-examined regarding facts not in evidence to test his qualifications, skills, and credibility or to test the validity and weight of his opinion." State v. Brooks, 960 S.W.2d 479, 493 (Mo. banc 1997).

Counsel

should be granted wide

latitude when cross-examining

an expert witness to test

these matters. Id.

Regarding the testimony of

Dr. Stacy, the prosecution

was permitted to test the

validity and weight of the

testimony by cross-examining

the doctor concerning his

knowledge of the facts

surrounding appellant's

prior hospitalizations.

The fact that appellant had checked into the hospital after choking his wife implicitly suggests that appellant's mental state with respect to the killing of Brandie Kearnes and Wayne Hoewing may have been a result of the killing rather than a cause of the killing. The state was entitled to raise the suggestion.

An identical analysis can be applied to the testimony of Dr. Peters. Dr. Peters testified that he relied on appellant's past interactions with others when making his diagnosis. Dr. Peters' testimony regarding appellant's violent behavior toward a co-worker was clearly relevant to the weight and validity of his testimony, particularly with respect to the doctor's diagnosis of appellant as suffering from narcissistic personality disorder with obsessive-compulsive traits.

Appellant also argues that the testimony of Dr. Stacy and Dr. Peters was more prejudicial than probative. This Court disagrees. Any prejudice that may have resulted from the mention of appellant's choking of his wife or fight with a coworker was nullified in advance of the testimony of both experts by the court's instruction to the jury not to consider the testimony as evidence that appellant did or did not commit the acts charged against him. State v. Madison, 997 S.W.2d 16, 21 (Mo. banc 1999).

In a related contention, appellant asserts that the prosecutor impermissibly argued to the jury before it retired to determine a guilt phase verdict, "[appellant] planned their murder and he is trying to cook up some kind of psychiatric mumbo-jumbo to get him out of it just like he's done before." Appellant argues that this statement, too, was an attempt to introduce evidence of uncharged crimes to the jury. Defense counsel did not object to this statement, so review is for plain error.

Relief should rarely be granted on an assertion of plain error with respect to a closing argument. State v. Deck, 994 S.W.2d 527, 544 (Mo. banc 1999). Relief is not warranted here. The comment was made in the context of the prosecution's urging the jury to find that the murders were of the first degree. The prosecutor made no reference to Dr. Stacy or Dr. Peters, their testimony, or to any specific act of appellant when he mentioned what appellant did "before."

This case is not, therefore, similar to State v. Burnfin, 771 S.W.2d 908 (Mo. App. 1989), on which appellant relies. In that case, the prosecutor made reference to the defendant's experience with knives and bombs, threats made by the defendant toward his mother and sister, a theft by the defendant, and an episode in which the defendant attacked his stepfather with a pitchfork. Burnfin, 771 S.W.2d at 912.

In the present case, furthermore, the prosecutor did not argue to the jury that it should consider appellant's having choked his former wife as evidence that appellant was guilty of the murders of Brandie Kearnes and Wayne Hoewing. Appellant has not borne the burden of establishing that the court plainly erred when it did not interrupt the state's argument.

VII.

Appellant

maintains that the trial

court erred in denying

appellant's motion for a

mistrial after the following

discourse occurred between

the prosecutor and Officer

Hall:

Q. (To Hall) When [appellant]

was transported to the

ambulance did you assist in

that process in any manner?

A. Yes. I helped carry the gurney and roll the gurney to the ambulance.

Q. Did you remain there while Mr. Smith was placed in the ambulance?

A. Yes, I did. I remained with Mr. Smith the whole time.

Q. At that point in time, what did you do?

A. We put Mr. Smith in the ambulance and I got in the ambulance with him and advised him of his Miranda Rights.

Following this exchange, appellant's counsel approached the bench and requested a mistrial, asserting that Officer Hall had improperly commented on appellant's post-arrest silence. The prosecutor responded that Officer Hall had not improperly commented on appellant's post-arrest silence, but that the trial court should instruct the jury to disregard Officer Hall's statement that he had advised appellant of his Miranda rights. Appellant's counsel opposed an instruction on the ground that such an instruction would merely serve to highlight Officer Hall's testimony. No instruction was given.

Appellant suggests that the exchange between the prosecutor and Officer Hall stripped him of his right not to speak at his criminal trial. State v. Cheatum, 520 S.W.2d 695 (Mo. App. 1975), is dispositive of this case. In Cheatum, as in this case, a police officer testified for the state that he had arrested the defendant and then advised him of his Miranda rights. Id. at 696.

The defendant, like appellant, argued that in so testifying that the police officer had improperly commented on the defendant's post-arrest silence. Id. The court rejected the defendant's argument, noting that the officer did not elaborate the Miranda rights. Id. at 697. The court also noted that there was no evidence regarding what appellant understood by the rights, and that the officer did not comment on the fact that the defendant failed to respond after being read his Miranda rights. Id. According to the court,

[i]t would be pure speculation to conclude, as does appellant, that the jury properly understood the warning of rights to require a response from appellant. It is not logical to say that the right of an accused to remain silent is violated by informing a jury that he had been accorded that right.

Id. The trial court did not err in failing to grant appellant's motion for a mistrial on this point.

VIII.

Appellant complains of several of the prosecutor's statements made during the state's guilt and penalty phase closing arguments. Appellant suggests that the statements prejudiced his cause in a number of ways: by suggesting that the jurors would have to explain their decision to friends and family after the trial; by suggesting that appellant has a propensity for behaving in a manner consistent with his guilt of the charged offense; by turning the prosecutor into an unsworn witness not subject to cross-examination; and by diminishing the jurors' sense of responsibility.

During the state's guilt phase closing argument, the prosecutor said, "frankly, ladies and gentlemen, anything less than murder in the first degree to those to [sic] people is an insult. [Appellant] planned their murder and he is trying to cook up some kind of psychiatric mumbo-jumbo to get him out of it just like he's done before." During the state's closing argument in the penalty phase, the prosecutor referred to appellant's "pattern of behavior" and "history of violence towards women." Also during the penalty phase closing argument, the prosecutor stated, "[appellant's] death will be a thousand times more merciful than Brandie's. His death will be a thousand times more merciful than Wayne's. He gave them no judge, he gave them no lawyer, he gave them no appeal."

Appellant contends that, when defense counsel failed to object, the trial court should have granted a mistrial sua sponte and that the trial court should have granted a mistrial pursuant to the requests of defense counsel on another occasion. Mistrial is a drastic remedy, however. State v. Brown, 998 S.W.2d 531, 549 (Mo. banc 1999). The decision whether to grant a mistrial is left primarily to the trial court, which is in the best position to determine whether the complained-of incident had any prejudicial effect on the jury. State v. Johnson, 968 S.W.2d 123, 134 (Mo. banc 1998).

This Court will reverse a conviction only if the challenged comments had a decisive effect on the jury verdict, meaning that there is a reasonable probability that, in the absence of the comments, the verdict would have been different. State v. Winfield, 5 S.W.3d 505, 516 (Mo. banc 1999), cert. denied, 120 S. Ct. 967 (2000).

With respect to the prosecutor's comment made during guilt phase closing argument that anything less than a finding of first degree murder would be an insult to Brandie Kearnes and Wayne Hoewing, the trial court did not plainly err by failing to declare a mistrial when the comment was made. Taking the entire closing argument into consideration, it is clear that the comment was made during a proper discussion of whether appellant's actions constituted murder in the first degree. Also, the comment "was isolated and brief, and was not emphasized by the prosecutor." Rousan, 961 S.W.2d at 851. The comment, furthermore, did not intimate to the jury that it would have to explain its actions to friends or family after the trial. Compare State v. Thomas, 780 S.W.2d 128, 133-35 (Mo. App. 1989).

Appellant's complaint

concerning the prosecutor's

statements about what

appellant did "before,"

appellant's "pattern of

behavior," and appellant's "history

of violence towards women"

is also without merit. This

Court addressed and rejected

appellant's contention that

the prosecutor's arguments

raised the possibility that

appellant was convicted of

his propensity to act

violently, rather than of

the crime charged, in the

previous point.

Appellant's last argument on

this point centers on the

prosecutor's argument that

"[appellant's] death will be

a thousand times more

merciful than Brandie's. His

death will be a thousand

times more merciful than

Wayne's. He gave them no

judge, he gave them no

lawyer, he gave them no

appeal."

At trial, defense counsel objected to the prosecution's statements. The court indicated that it would sustain the objection and instruct the jury to disregard the statement, but defense counsel told the judge that appellant did not want to highlight the statement and that declaring a mistrial was the "only relief." The trial court overruled the motion for a mistrial. Appellant now claims that the prosecutor's statements constituted unsworn testimony not subject to cross-examination and diminished the jurors' sense of responsibility by impermissibly commenting upon appellant's right to appeal.

The trial court did not abuse its discretion when it denied defense counsel's motion for a mistrial. The comment was not "unsworn testimony" from a prosecutor to the effect that the death penalty leads to a "quick and easy death." Compare State v. Storey, 901 S.W.2d 886, 901 (Mo. banc 1995); Antwine v. Delo, 54 F.3d 1357, 1362 (8th Cir. 1995).

Rather, the prosecutor's statement was offered to rebut appellant's arguments to the effect that appellant deserved mercy. As defense counsel apparently understood when he said to the jury in his own closing argument that "[the state] may try to argue that [appellant] was not merciful so you shouldn't be," the prosecutor has considerable leeway to make arguments in rebuttal during the state's closing argument. State v. Middleton, 998 S.W.2d 520, 530 (Mo. banc 1999), cert. denied, 120 S.Ct. 1189 (2000). Defense counsel "may not provoke a reply and then assert error." Id.

Neither was the prosecutor's statement an impermissible comment on appellant's right to appeal. Only in the most oblique sense was the statement that Brandie Kearnes and Wayne Hoewing received no appeal a reference to appellant's own right to appeal. Even assuming, however, that the jury might have perceived it as such, the statement is prejudicial only if it misleads the jury as to its role in the sentencing process. State v. Richardson, 923 S.W.2d 301, 321 (Mo. banc 1996).

Here the likelihood, if any, that the jury was misled was momentary and de minimis. The jury was properly instructed, furthermore, as to its responsibilities regarding whether the death penalty was appropriate. MAI-CR3d 313.49. Appellant does not demonstrate that the prosecutor's comments had anything approaching a decisive effect on the jury's reasoning. This point is, therefore, denied.

IX.

Appellant argues that evidence regarding prior, unadjudicated acts of violence should not have been admitted during the penalty phase of his trial because the state did not provide notice that it intended to submit the acts as non-statutory aggravating circumstances. Defense counsel requested disclosure of the statutory and non-statutory aggravating circumstances that the state intended to submit to the jury.

The state, although it complied with the request to disclose statutory aggravating circumstances, argued to the trial court that it was not required to disclose non-statutory aggravating factors, and the court agreed. On appeal, appellant complains specifically of the testimony of Muriam Daniels and Mary Smith, the state's first two witnesses during the penalty stage. Both women testified regarding violent encounters they had with appellant. Defense counsel did not object to this testimony.

"Generally, both the state and the defense are given wide latitude to introduce any evidence regarding the defendant's character that assists the jury in determining the appropriate punishment." Thompson, 985 S.W.2d at 792. "This includes evidence of serious unconvicted crimes." Id. This latitude is slightly circumscribed, however, by the requirement that the state give notice to a criminal defendant concerning the "aggravating circumstances...which the State intends to submit to the jury for its consideration." State v. Debler, 856 S.W.2d 641, 657 (Mo. banc 1993). In Debler, this Court explained how admission of unadjudicated bad acts evidence could prejudice a criminal defendant, stating

[b]ecause no jury or judge has previously determined a defendant's guilt for uncharged criminal activity, such evidence is significantly less reliable than evidence related to prior convictions. To the average juror, however, unconvicted criminal activity is practically indistinguishable from criminal activity resulting in convictions, and a different species from other character evidence.

Id.

First, it is worth noting

that appellant received some

information, albeit

informally, about the nature

of the non-statutory

aggravating circumstances

that the state intended to

submit. The state

specifically endorsed

Daniels and Smith as

potential witnesses. Daniels

in particular was endorsed

as a "second stage" witness.

The relationships between

appellant and Daniels and

Smith and appellant's

violent behavior toward both

women were detailed in

several reports that were

disclosed to defense counsel

in a timely fashion. This is

not to suggest that the

state properly notified

appellant of the non-statutory

aggravating circumstances.

The state

has a duty specifically to

disclose such aggravating

circumstances to the defense

when the defense asks for

disclosure. Id.

Assuming that the trial

court's decision to admit

the testimony of Muriam

Daniels and Mary Smith was

error, the question remains

whether the lack of notice

and the admission of the

testimony was plain error

constituting manifest

injustice because the claim

of error was not preserved.

State v. Worthington,

8 S.W.3d 83, 90 (Mo. banc

1999). This Court looks to

the totality of the

circumstances in order to

determine whether manifest

justice resulted from the

trial court's error. Id.

Taking into account the totality of the circumstances, it cannot be said that appellant suffered the prejudice of which Debler warned. The violent episodes about which Daniels and Smith testified, although technically unadjudicated, were once the subject of judicial consideration; both Daniels and Smith obtained restraining orders against appellant in an effort to curb his aggressive behavior toward them. The testimony is, therefore, more reliable than the evidence introduced in Debler.

In addition, as noted, the state specifically endorsed both women as potential witnesses, and Daniels was endorsed as a "second stage" witness. The relationships between appellant and Daniels and Smith and appellant's violent behavior toward both women were detailed in several reports that were disclosed to defense counsel in a timely fashion. In light of these facts, it cannot be said that the trial court's decision to admit the testimony of Daniels and Smith during the penalty phase of the trial resulted in manifest injustice.

Appellant also contends that the trial court should not have admitted the testimony of Daniels and Smith because the acts they described were too remote in time to be relevant. This argument has no merit. Remoteness goes to the weight of the evidence, not to admissibility. State v. Shaw, 847 S.W.2d 768, 778 (Mo. banc 1993).

X.

Appellant focuses upon the testimony of two of Brandie Kearnes's family members at appellant's sentencing hearing. Bridie Kearnes, Brandie's sister, stated that appellant "deserves to die" and that she could not survive if appellant "is given life." Yvonne Kurz then opined that the death penalty was "too good" for appellant. Appellant argues that when the trial court overruled defense counsel's objection to this testimony, the court "made clear that it would consider improper and inflammatory evidence in deciding whether to sentence [appellant] to die."

Appellant's position is foreclosed by State v. Taylor, 944 S.W.2d 925 (Mo. banc 1997). In that case, the state conceded that the victim's family members' testimony concerning the appropriate sentence was inadmissible under Payne v. Tennessee, 501 U.S. 808 (1991). This Court held, nevertheless, that prejudice sufficient to result in reversal could not be demonstrated "because judges are presumed not to consider improper evidence during sentencing." Taylor, 944 S.W.2d at 938.

Appellant has not overcome that presumption in this case. The trial court, when it sentenced appellant, stated:

The Court further finds that the evidence supports the jury's verdicts of guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. The Court finds the evidence supports the jury's findings beyond a reasonable doubt that statutory, aggravating circumstances exist as to both the murder of Brandie Kearnes and Wayne Hoewing. The Court further finds there are facts and circumstances which taken as a whole warrant imposition of the sentence of death as to both Counts I and II. The Court finds there are not facts and circumstances in mitigation of punishment sufficient to outweigh the evidence in aggravation of punishment as to both Counts I and II.

It is evident from the record that the trial court considered only the facts and circumstances of appellant's case when it sentenced appellant to death. In light of this, this Court refuses to accept appellant's argument that because the trial court overruled defense counsel's objection it necessarily also took the testimony of Kearnes and Kurz into account when imposing sentence.

XI.

Appellant asserts that the trial court erred in submitting Instruction Nos. 31 and 36 and in accepting the jury's finding that appellant committed murder while he was engaged in the perpetration of a burglary because the instructions were improperly drafted in that the definition of "burglary" in the instructions, as to each victim, should have specified that appellant had the purpose of committing murder when he entered the Hoewing residence. See MAI-CR3d 313.40, Notes on Use 8; MAI-CR3d 333.00.

Appellant is correct that the third statutory aggravating circumstance listed in Instruction Nos. 31 and 36 was not correctly drafted. The aggravating circumstance, authorized by section 565.032.2(11), RSMo 1994, was drafted for the instructions as follows:

3. Whether the murder of Brandie Kearnes was committed while the defendant was engaged in the perpetration of a burglary. A person commits the crime of burglary when he knowingly enters unlawfully or remains unlawfully in a building or inhabitable structure for the purpose of committing a crime therein.

(Emphasis added). The instructions should have specified that appellant had the purpose of committing murder, not "a crime therein."

Although submission of the relevant portions of Instruction Nos. 31 and 36 was error, appellant was not prejudiced by the submission. State v. Bucklew, 973 S.W.2d 83 (Mo. banc 1998), cert. denied, 525 U.S. 1082 (1999), is instructive. There this Court held that "[i]f the jury finds a contemporaneous, multiple-crime event, the minimum threshold for imposition of the death penalty is crossed." Id. at 95.

In the present case, the jury found that appellant unlawfully entered the Hoewing residence for the purpose of committing a crime. This means that the jury found that appellant was engaged in committing more than one crime. The only evidence before the jury with respect to any other intended "crime therein" was the crime of murder. As a consequence, appellant's argument that the relevant portion of the instructions constituted giving a roving commission to the jury to decide which offense was intended is without merit.

Based on

this circumstance, it is not

apparent to this Court that

the failure to specify the

crime affected the jury's

verdict.

Appellant's apparent

reliance on State v.

Politte, 886 S.W.2d 946

(Mo. App. 1994), is

misplaced. In Politte,

the court of appeals

reversed and remanded for a

new trial after the trial

court omitted the intended

crime from the verdict

director. The defendant was

charged and convicted of

attempted burglary in the

first degree. From the

report of the case, it is

evident that there was no

other evidence before the

jury with respect to any

other intended "crime

therein." As a consequence,

the case is entirely

distinguishable from the

present case.

In a related contention, appellant asserts that the state presented insufficient evidence from which a rational juror could have found beyond a reasonable doubt that appellant committed a burglary in that there was no evidence of any intended crime. Appellant's assertion is without merit because, as stated above, the intended crime was murder and the evidence supporting murder was sufficient.

Even assuming, arguendo, that the erroneous portion of the instruction were to be stricken, the penalty must be upheld. For each sentence of death, the jury found the existence of at least one other statutory aggravating circumstance, which is all that is required for the jury to recommend imposition of the death penalty. Middleton, 998 S.W.2d at 530.

Citing Tuggle v. Netherland, 516 U.S. 10 (1995), appellant argues that if the jury had not had the third aggravating circumstance before it, it might have found that the evidence in mitigation outweighed the aggravating circumstance evidence. Tuggle is not controlling. There the defendant was precluded from developing mitigation evidence. Id. at 12. That error invalidated a related statutory aggravating circumstance. Id.

On remand the lower court reaffirmed the petitioner's sentence of death because the jury had found the existence of two statutory aggravating circumstances, one being sufficient to support the sentence. Id. The United States Supreme Court then vacated the sentence. Id. at 14. The Court's vacation of sentence rested on the fact that the defendant had not been permitted to present evidence in mitigation. Id. at 13-14. As a consequence, the jury's ultimate decision may have been affected. Id. at 14. In the present case, appellant was not precluded from introducing any mitigating evidence. Based upon a similar distinction, appellant's reliance upon Antwine v. Delo, 54 F.3d 1357 (8th Cir. 1995), is misplaced. The trial court did not err in submitting the instructions and in accepting the jury's finding that appellant committed murder while he was engaged in the perpetration of a burglary.

XII.

Appellant asserts that the trial court plainly erred during the penalty phase in admitting Exhibits 90D and 90G, certified copies of appellant's prior convictions for felony stealing and violation of an order of protection. Appellant also contends that the trial court plainly erred in failing to instruct the jury about how to evaluate this evidence. Because appellant failed to object to the admission of this evidence before the trial court, review is for plain error. Winfield, 5 S.W.3d at 511. Appellant must show that the trial court's error so substantially affected his rights that manifest injustice will result if the error is left uncorrected. Winfield, 5 S.W.3d at 516.

Appellant's assertions lack merit. During the penalty phase, the sentencer should generally receive any and all evidence that aids it in assessing punishment. State v. Morrow, 968 S.W.2d 100, 114 (Mo. banc), cert. denied, 119 S. Ct. 222 (1998); sec. 565.032.1(2). It is well established that the sentencer may consider a defendant's prior convictions. State v. Clay, 975 S.W.2d 121, 138 (Mo. banc 1998), cert. denied, 119 S. Ct. 834 (1999); State v. Simmons, 955 S.W.2d 729, 740-41 (Mo. banc 1997); State v. Smulls, 935 S.W.2d 9, 22-23 (Mo. banc 1996). Section 565.032.2(1) allows the jury to receive a statutory aggravating circumstance instruction when "[t]he offense was committed by a person with a prior record of conviction for murder in the first degree, or the offense was committed by a person who has one or more serious assaultive criminal convictions."

Nothing in this section prohibits the introduction of a defendant's prior convictions for other purposes during the penalty phase. Furthermore, the jury was properly instructed to consider all evidence in aggravation and mitigation of punishment in Instruction Nos. 32-33 and 37-38. Sec. 565.032.1(2). There is no error.

XIII.

Appellant contends that the trial court plainly erred in allowing the victims' relatives, Monty Kearnes, Sandy Kearnes, Mark Hoewing, and Yvonne Hoewing, to testify about the lives of Brandie Kearnes and Wayne Hoewing without instructing the jury on how to evaluate the evidence.

There is no plain error. Victim impact evidence is admissible in capital cases unless the evidence "is so unduly prejudicial that it renders the trial fundamentally unfair...." State v. Middleton, 995 S.W.2d 443, 464 (Mo. banc), cert. denied, 120 S. Ct. 598 (1999) (quoting Payne v. Tennessee, 501 U.S. 808, 824 (1991)). In State v. Basile, 942 S.W.2d 342, 359 (Mo. banc 1997), this Court ruled that a jury need not be instructed about how to evaluate victim impact evidence so long as the jury is properly instructed about how to consider all evidence in aggravation and mitigation of punishment. The jury was properly instructed here, through Instruction Nos. 32-33 and 37-38.

Appellant also asserts that the trial court plainly erred in allowing Muriam Daniels, appellant's former girlfriend, and Mary Smith, appellant's former wife, to testify in the penalty phase that appellant, during their relationships with him, had been verbally and physically abusive to them without instructing the jury how to evaluate this evidence.

The trial court did not plainly err in admitting this evidence without instruction. In State v. Ervin, 979 S.W.2d 149 (Mo. banc 1998), cert. denied, 525 U.S. 1169 (1999), this Court rejected the argument made by appellant here. In Ervin, this Court held that the trial court did not err because the instructions it gave to the jury were consistent with section 565.032.1(2), RSMo 1994, which states that a jury in the penalty phase of a capital case "shall not be instructed upon any specific evidence which may be in aggravation or mitigation of punishment, but shall be instructed that each juror shall consider any evidence which he considers to be aggravating or mitigating." Id. at 159.

Likewise, in the present case, the instructions the jury received, Nos. 32-33 and 37-38, are consistent with section 565.032.1(2). There is no error, plain or otherwise, in admitting this evidence without instruction. To the extent, furthermore, that appellant argues in this point that the testimony of Muriam Daniels and Mary Smith concerning unadjudicated bad acts should not have been admitted under any circumstances, his contentions have already been considered and rejected elsewhere in this opinion.

XIV.

Appellant argues that the "depravity of mind" and "multiple murder" aggravating circumstances submitted to the jury are unconstitutionally vague since they do not distinguish his case from those where the death penalty is not imposed. With respect to "depravity" in particular, appellant suggests that the aggravating circumstance does not limit or channel the discretion of the jury because jurors could reasonably find that all murders are "outrageously wanton or vile" and that they all involve physical pain or emotional suffering. Appellant's argument is not well taken. The instruction defined "depravity."

Furthermore, this Court has repeatedly rejected such attacks with regard to both the depravity of mind aggravating circumstance, State v. Knese, 985 S.W.2d 759, 778 (Mo. banc 1999); State v. Barnett, 980 S.W.2d 297, 309 (Mo. banc 1998); State v. Clay, 975 S.W.2d 121, 145 (Mo. banc 1998); and the multiple murder aggravating circumstance, Barnett, 980 S.W.2d at 309; State v. Carter, 955 S.W.2d 548, 558-59 (Mo. banc 1997); State v. Powell, 798 S.W.2d 709, 715 (Mo. banc 1990). This Court again rejects these attacks.

XV.

Appellant claims that his death sentences are disproportionate under section 565.035, RSMo 1994, because they are based upon several arbitrary factors and upon invalid aggravating circumstances. In addition, appellant argues that section 565.035 as applied by this Court violates his due process rights because the Court has an inadequate database on which to rely, the Court compares only those cases in which the death penalty has been imposed, and appellant did not receive adequate notice of the procedure to be followed or a meaningful opportunity to be heard.

It is the duty of this Court independently to review appellant's sentences to determine (1) whether they were imposed under the influence of passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor; (2) whether the evidence supports the jury's finding of a statutory aggravating circumstance and any other circumstance found; and (3) whether the sentences are excessive or disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar cases, considering the crime, the strength of the evidence, and the defendant. Sec. 565.035.3.

Appellant's claims

concerning passion,

prejudice, and "many"

arbitrary factors are

premised upon his arguments

from his various points on

appeal, which this Court has

already rejected. Similarly,

appellant's arguments

concerning the invalidity of

the aggravating

circumstances have already

been rejected. This Court

finds, therefore, that

appellant's sentences were

not the result of passion,

prejudice, or any arbitrary

factors.

During the course of this

Court's consideration of

appellant's arguments,

furthermore, this Court has

found that the evidence

supports the jury's findings

of the aggravating

circumstances.

The record shows that appellant broke into the Hoewing residence and attacked Brandie Kearnes, stabbing or cutting her eight times. He then attacked Wayne Hoewing and taunted Wayne to shoot him after inflicting eleven stab or cut wounds. Appellant then left both victims to die.

These facts support the jury's findings that the murder of Brandie Kearnes was committed while appellant was engaged in the commission of another unlawful homicide, that Brandie's murder was committed while appellant was engaged in the perpetration of a burglary, that Wayne Hoewing's murder was committed while appellant was engaged in the commission of another unlawful homicide, that Wayne's murder was committed while appellant was engaged in the perpetration of a burglary, and that Wayne's murder involved depravity of mind in that the murder was wantonly vile, horrible, and inhuman.

An independent review of the facts of this case also reveals that appellant's sentences are not disproportionate. Death sentences have frequently been upheld where the defendant murdered multiple victims or murdered during the perpetration of a burglary. See, e.g., Middleton, 998 S.W.2d at 531; State v. Barnett, 980 S.W.2d 297, 310 (Mo. banc 1998); State v. Johnson, 968 S.W.2d 123, 135 (Mo. banc 1998); State v. Lyons, 951 S.W.2d 584, 599 (Mo. banc 1997).

Taking into account the crime, the strength of the evidence, and also the defendant, the Court finds that the death sentences in this case are proportionate to the death sentences imposed in other cases.

Appellant's claims concerning the constitutionality of section 565.035 also have no merit. Arguments concerning the adequacy of the database have been rejected in the past. State v. Johnson, 968 S.W.2d 123, 135 (Mo. banc 1998). So have arguments relating to the fact that this Court compares cases in which the death penalty was imposed to other cases in which the death penalty was imposed, about which the Court has said, "[t]he issue when determining the proportionality of a death sentence is not whether any similar case can be found in which the jury imposed a life sentence, but rather, whether the death sentence is excessive or disproportionate in light of 'similar cases' as a whole." State v. Clay, 975 S.W.2d 121, 146 (Mo. banc 1998) (quoting State v. Mallett, 732 S.W.2d 527, 542 (Mo. banc), cert. denied 484 U.S. 933 (1987)). Claims involving notice and a meaningful opportunity to be heard have also been addressed and rebuffed. Clay, 975 S.W.2d at 146. Once again, this Court rejects these claims.

XVI.

The judgment is affirmed.******

Footnotes:

FN1. Appellant cites the same federal and state constitutional provisions for each of his points of error on appeal.

FN2. Appellant conceded another point on appeal, concerning the trial court's decision to overrule defense counsel's motion to strike for cause a venireperson, at oral argument. The venireperson did not in fact serve on appellant's jury. Sec. 494.480.4, RSMo 1994.

FN3. In addition to the various federal and state constitutional provisions that appellant raises with respect to every point on appeal, in this point he also cites Mo. Const. art. I, sec. 17.

FN4. In addition to the various federal and state constitutional provisions that appellant raises with respect to every point on appeal, in this point he also cites Mo. Const. art. I, sec. 17.

*****

Separate Opinion:

Dissenting opinion by Michael A. Wolff, Judge:

In a fundamental way, the principal opinion damages the integrity of the legal profession. There is no dispute that the prosecutor in this case had represented Smith in two previous criminal cases as his defense attorney. Moreover, the prosecutor -- Smith's erstwhile defender -- used one of those convictions in persuading the jury to impose the death penalty on his former client.

If this were simply a case where the prosecutor is using the prior conviction, a matter of public record equally available to all prosecutors, I could be tempted to join in the principal opinion.