During August 1952, Dovie gave

Hawkins arsenic on four occasions, dumping the powder in his milk.

Once, when Hawkins came down with severe stomach pains, she called the

ambulance that took him to the hospital. This, she claimed, showed

that she did not kill her husband.

She admitted giving him some

powder, but said it was at his request for a headache.

By August 22, 1952, Hawkins was

dead. An autopsy revealed the obvious signs of arsenic poisoning

(bright red organs) and Dovie was brought in for questioning.

She initially blamed the murder

on her son.

The young man “became hysterical

when told his mother had accused him of the crime,” Dericks told the

press. Her interrogators, convinced of her son’s innocence, pressed

her for information and she admitted she killed her husband.“If a

mother can make such a charge against her son, wouldn’t she be capable

of killing?” Dericks asked her. “Don’t you want to change your story?”

“And take the blame myself?”

Dovie asked. A few moments later she spoke again.

“Yes, I want to change my

story,” she said, matter-of-factly. “I did it.”

She told police that Hawkins

could not satisfy her and that led to several arguments. Eventually he

threatened to kill her, she said.

“I got him before he got me,”

she told them.

“He wanted a housekeeper,” she

said. “I wanted a home.”

Dovie was interviewed by a

University of Cincinnati psychiatrist who found her sane, but with a

flattened affect.

“I examined her after her

arrest,” said Dr. Robert Buckley. “I found she is not insane. She was

sad and melancholy, and on the verge of tears several times, but the

tears would not come.”

During her brief trial, Dovie

sat stony still and obdurate, telling friends that “I cannot cry.”

Her only argument in defense was

that she confessed to shield her son from an earlier marriage who

actually committed the crime.

The jury took just 40 minutes to

convict her without a recommendation for mercy.

Her emotionless exterior nearly

broke when the verdict came, and she tensed briefly before leaning

back in her chair. When she was escorted from the courtroom, her icy

demeanor contrasted with the cries of anguish from her family.

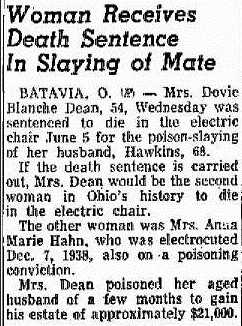

Under Ohio law at the time, the

judge was required to sentence her to death.

Dovie became the second woman to

be sentenced to die in the electric chair; the first was Anna Marie

Hahn, another poisoner.

Hahn died screaming in terror,

pleading for her life. Dovie Dean was an ice queen to the end.

Before moving to the Ohio State

Pentitentiary from Marysville Reformatory, she managed to gain 30

pounds and kept a pet parakeet she named “Charlie.”

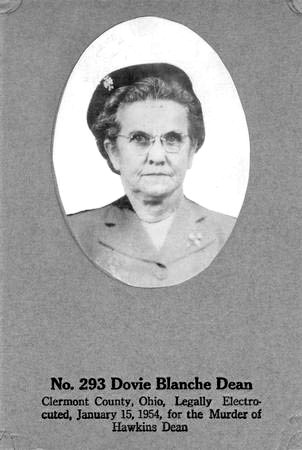

On January 15, 1954, she sat

with her spiritual advisor in the anteroom outside the death chamber,

drinking coffee and taking a pass on the cookies. Shortly before it

came time to move into the execution room, the top of her head was

shaved to allow for better contact with the electrode, and as a last

request she asked that someone sing “What a Friend We Have in Jesus.”

Oddly, perhaps because none of

the persons present was confident in his singing voice, her request

was denied. The Rev. C.W. Wilsher read the hymn to her.

Dovie sat down in the electric

chair, her chapped red hands gripped the armrest tightly and she made

her final statement.

“When I got on the witness

stands they made light of me because I couldn’t cry,” she said. “Years

ago, I couldn’t have faced all of those people, but I asked God to

help me. I had grief inside like knives.”

Precisely at 8 p.m., the warden

ordered that the switch be pulled. More than 1,900 volts coursed

through her body and at 8:07 p.m., Dovie Dean was dead.

MarkGribben.com