Lois solicited three men, Buchanan, Music and Hart

to kill her husband, and formulated a plan for him to be shot on a

certain isolated road where her husband drove. she insisted that a

shotgun with deer slugs be used, and directed that his wallet be

returned to her because it had important papers in it.

One night the three men joined Lois in her trailer

while her husband was gone and insisted that he be killed that night.

The men left, assuring her that it would be done.

The plan was executed by placing a log in the road

which forced Mr. Thacker to stop. When he got out of his truck, he was

shot by Music. Buchanan removed the wallet which was returned to Lois

that night.

During her efforts to induce the men to kill Mr.

Thacker, Lois told them that she wanted him killed just like she and

Mr. Thacker had killed her first husband, Phillip Huff. Buchanan,

Music and Hart all testified against Lois at trial after entering into

plea agreements.

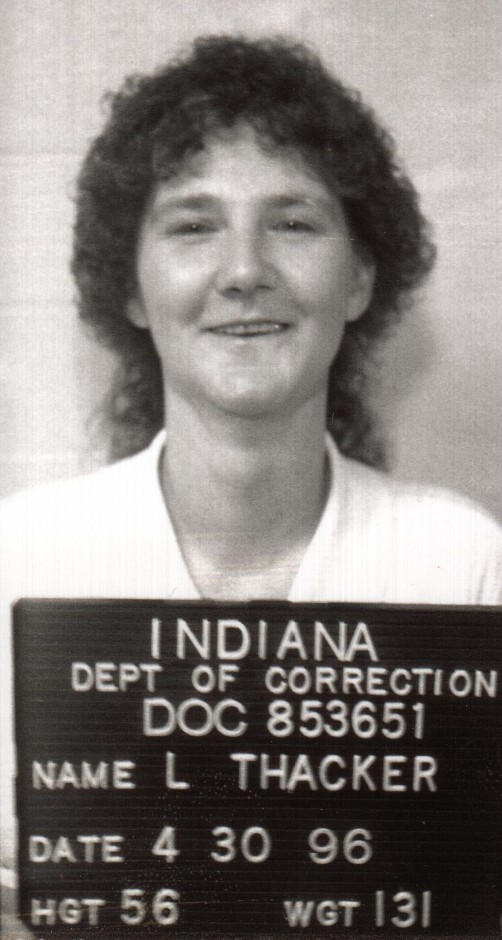

Thacker v. State

No. 1285 S 506.

Linley E. Pearson, Atty. Gen., Cheryl L. Greiner,

Deputy Atty. Gen., Indianapolis, for appellee

DeBRULER, Justice.

Appellant was charged in Count I pursuant to I.C.

35-42-1-1(1) with the knowing killing of her husband, John E. Thacker,

by shooting. In a separate Count II, the prosecution sought the

sentence of death by alleging pursuant to I.C. 35-50-2-9(b)(3) the

aggravating circumstance that the killing had been accomplished while

lying in wait. The trial court permitted Count II to be amended by

adding a second aggravating circumstance pursuant to I.C.

35-50-2-9(b)(5) that the killing had been done by one Donald Ray

Buchanan, Jr., who had been hired by appellant to do so.

A trial by jury resulted in a verdict of guilty as

charged in Count I. A judgment of conviction was then entered on the

verdict. The following day, the jury reconvened for the penalty phase

of the trial. Following the presentation of evidence, the jury retired

and then returned a verdict recommending that the death penalty be

imposed.

The cause next came on for sentencing. The trial

court expressly found that the State had proved both aggravating

circumstances beyond a reasonable doubt. The Court further concluded

that the mitigating circumstances were outweighed by the two

aggravating circumstances and ordered death.

The evidence on behalf of the State is in substance

as follows: During a period of several weeks, appellant spoke with

three young men, Buchanan, Music and Hart, expressing her desire to

have her husband, John Thacker, killed and encouraging and challenging

each to do so. Her husband had a life insurance policy of which she

was beneficiary. There was conflict between husband and wife. She

formulated a plan and guided its execution, demanding that he be

killed by shooting with a shotgun loaded with deer slugs, providing

some ammunition, picking out for the trio a location along a road near

their residence on which her husband drove and where he might be

stopped and killed without notice, and directing that his wallet be

taken following the assault because it contained an important paper.

One night, the three joined appellant at her

trailer. She requested that her husband be killed that night, and one

of the three said that it would be done. The trio then left her

trailer and drove from it a short distance up a hill to the site along

the road which had been previously pointed out by appellant, where,

armed, they put a log across the road, hid, and waited for John

Thacker to come along. He drove up in his truck and stopped to remove

the log. He was then shot and killed by Music. Buchanan removed his

wallet. Two of the

[ 556 N.E.2d 1318 ]

men returned to appellant's trailer, reporting to

appellant their act and delivering the wallet. She then received some

shotgun shells from them, which she put into the trash. She provided

one of the men with a change of clothing and put his mud-stained

clothes into her washing machine.

I.

In the first of ten appellate claims, appellant

contends that the trial court erred when permitting the State to amend

Count II, death penalty, by adding to such count the allegation of

murder by hire as a second aggravating circumstance. The person

alleged to have been hired was Buchanan. I.C. 35-50-2-9(b)(5) sets

forth such aggravating circumstance as, "The defendant committed the

murder by hiring another person to kill." The initial Count II was

based upon the single aggravating circumstance of murder by lying in

wait. I.C. 35-50-2-9(b)(3) sets forth such aggravating circumstance

as, "The defendant committed the murder by lying in wait."

The initial Count II, death penalty, was filed with

the original information on November 5, 1984. At a pre-trial

conference on February 7, 1985, the case was set for trial to commence

on April 30. The voir dire examination of prospective jurors commenced

on April 30 and was completed on May 9. On May 2, in the midst of voir

dire, the State filed its amended version of Count II. The court

refused to permit some amendments to be made, but subsequently

permitted the one adding the allegation of the aggravating

circumstance of hiring another person to kill, over a defense

objection.

The accused in a criminal prosecution has a basic

right to reasonable notice and a fair opportunity to be heard and to

contest outright charges, recidivist charges, and death penalty

charges. Oyler v. Boles,368 U.S. 448, 82 S.Ct. 501, 7 L.Ed.2d 446

(1962); Daniels v. State (1983), Ind., 453 N.E.2d 160; Barnett v.

State (1981), Ind., 429 N.E.2d 625. The amendment of an information to

add an additional such charge is permitted and is governed by I.C.

35-34-1-5(c). Hutchinson v. State (1983), Ind., 452 N.E.2d 955. Such

an amendment, including one adding an additional aggravating

circumstance for imposition of the death penalty, may be approved at

any time so long as it does not prejudice the substantial rights of

the defendant. Williams v. State (1982), Ind., 430 N.E.2d 759, appeal

dismissed, 459 U.S. 808, 103 S.Ct. 33, 74 L.Ed.2d 47, reh'g denied,

459 U.S. 1059, 103 S.Ct. 479, 74 L.Ed.2d 626.

In this case, appellant was confronted with the new

allegation of having hired Buchanan to kill her husband in the middle

of voir dire examination of prospective jurors after having exercised

some, but not all, of her peremptory challenges. Thus appellant claims

prejudice to her right to peremptory challenges in that she was

required to exercise some without knowledge of the second allegation.

According to I.C. 35-37-1-3(a), the defendant in a

capital case is granted twenty peremptory challenges. The record shows

that appellant exercised three such challenges prior to the filing of

the amended information by the State. Thus, many peremptory challenges

remained after the defense was aware of the new allegation. The record

also discloses that Buchanan, the party allegedly hired by appellant,

had been listed as a witness by the State. The State took his

deposition on February 15, 1985, and continued with two additional

sessions on February 20 and April 18, to completion. Thus, appellant

was provided with an opportunity to know before commencing voir dire

examination on April 30 that she would be faced with the testimony of

Buchanan. Moreover, sixteen days elapsed between the filing of the

amended information and the commencement of the trial on the death

count. These days were available to the defense to develop a strategy

to contest the new allegation.

Upon consideration of all the circumstances

presented which tend to place this amendment in perspective, we find

that there is no sufficient showing that substantial rights were

prejudiced or that an impingement of due process occurred. There was

no error.

[ 556 N.E.2d 1319 ]

II.

It is next claimed that the trial court erred by

excusing for cause several jurors during voir dire of the jury panel

because of their views on the death penalty. The Sixth Amendment

requires that "if prospective jurors are barred from jury service

because of their views about capital punishment on `any broader basis'

than inability to follow the law or abide by their oaths, the death

sentence cannot be carried out." Adams v. Texas,448 U.S. 38, 48, 100

S.Ct. 2521, 2528, 65 L.Ed.2d 581, 591 (1980) (citing Witherspoon v.

Illinois,391 U.S. 510, 88 S.Ct. 1770, 20 L.Ed.2d 776 (1968)). In

reviewing whether a prospective juror was properly excluded, the

totality of the questioning is to be considered. Davis v. State

(1986), Ind., 487 N.E.2d 817. The Witherspoon doctrine applies to jury

selection for capital cases in Indiana, where the jury recommends the

death sentence to the judge and does not set it. Burris v. State

(1984), Ind., 465 N.E.2d 171, cert. denied, 469 U.S. 1132, 105 S.Ct.

816, 83 L.Ed.2d 809 (1985); Monserrate v. State (1971), 256 Ind. 623,

271 N.E.2d 420. Where the jury selection standards employed by the

trial court are not in accordance with the Witherspoon doctrine, a

reversal of the sentence is required, and the conviction may stand

unaltered. Lockhart v. McCree,476 U.S. 162, 106 S.Ct. 1758, 90 L.Ed.2d

137 (1986); Monserrate,256 Ind. 623, 271 N.E.2d 420.

The jury here recommended that death be imposed. We

therefore turn to decide whether the exclusion of prospective jurors

in the present case violated the Witherspoon doctrine. Of the fifteen

prospective jurors successfully challenged for cause on the basis of

their views regarding the death penalty, the questioning of two

defines the range of responses of the group. The most equivocal of the

group ended his questioning by counsel and the court as follows:

Judge Songer: ... . The key question then is can

you consider administering [the death penalty]?

A: I could consider it, I'm answering truthfully, I

guess I could.

Judge Songer: ... . "Under no circumstances could I

recommend to the judge that the death penalty be imposed?"

A. I lean toward that direction. I feel under no

circumstances. That's what I would have to answer truthfully.

The least equivocal of the group finally responded

as follows:

Judge Songer: ... . You're saying that under no

circumstances could you consider recommending the death penalty?

A: Right.

In all instances, the trial court received such

responses and sustained a challenge by the prosecution for cause over

the objection of defense counsel.

Each of these jurors was excluded in a manner

consistent with the requirements of the Sixth Amendment if he or she

held views which would prevent or substantially impair the performance

of his or her duties as a juror in conformity with the oath and the

jury instructions. Wainwright v. Witt,469 U.S. 412, 105 S.Ct. 844, 83

L.Ed.2d 841 (1985). The voir dire examination of these prospective

jurors commenced with a general expression that they had troubles with

the death penalty. There was early ambiguity in their testimony, as

they learned more about the process. Each, however, concluded with

statements in the nature of those quoted above. In each instance, the

record of voir dire examination provides a basis upon which the judge

was warranted in concluding that the individual held moral, religious

or ethical views which would have prevented or substantially impaired

his or her ability to find and evaluate aggravating and mitigating

circumstances and to make a recommendation as contemplated by the

death sentence statute. Consequently, the claim that the trial court

incorrectly sustained the challenges of the prosecution for cause is

not sustained.

III.

Appellant made a pre-trial motion in limine and

in-trial objections to the testimony of prosecution witnesses from

which it might be deduced that appellant and the victim Thacker had

shot and killed appellant's first husband, Phillip Huff, in 1983,

[ 556 N.E.2d 1320 ]

about two years before the 1984 shooting death of

Thacker. The trial court overruled both, ruling that the challenged

evidence was admissible as part of the res gestae of the charged crime

of killing Thacker.

Evidence of separate offenses committed by the

accused is generally inadmissible. Maldonado v. State (1976), 265 Ind.

492, 355 N.E.2d 843. Evidence tending merely to prove that the accused

has a bad character or criminal propensity is totally inadmissible.

Randolph v. State (1977), 266 Ind. 179, 361 N.E.2d 900. However, we

have recognized that "`happenings near in time and place' which

`complete the story of the crime on trial by proving its immediate

context'" (sometimes referred to as res gestae) are properly proved.

Maldonado, 265 Ind. at 495, 355 N.E.2d at 847 (quoting McCormick on

Evidence § 190 at 448 (2d ed. 1972)). Connie Busick, testifying on

behalf of the State, testified that when charting the plan to kill

Thacker, appellant said she wanted Buchanan to kill Thacker with a

deer slug, the same means she and Thacker had used to kill Huff.

Matthew Music testified that on the night of the shooting of Thacker,

appellant asked him whether he was going to help kill Thacker and that

when he said no, she told him that Thacker had killed Huff, who had

been Music's best friend. The other evidence challenged on this basis

was of like nature. At various stages of the trial, the trial court

responded to such evidence by instructing the jury not to consider

such matters pertaining to the death of Huff as evidence of

appellant's guilt of the charged crime.

These incriminating statements attributed to

appellant by the various witnesses were made in the formulation of the

plan to kill Thacker and during her efforts to induce others to

execute the plan. Their relevance was of the highest order and

outweighed their prejudicial value, especially in light of the

portrayal of Thacker as more culpable for Huff's death than appellant

and the trial court's admonitions to the jury to give the statements

limited consideration. The trial court properly permitted this

evidence to be presented, despite its tendency to show that appellant

had been an accomplice in a prior crime.

IV.

State's exhibits 4 and 5 are color photographs

depicting two fatal gunshot wounds to the body of the victim Thacker.

The photos are of the naked body of the victim after it had been

cleaned in preparation for an autopsy. Exhibit 4 depicts the upper

portion of the back of the victim and shows an oval hole, measuring

one and one-half inch by one inch. Exhibit 5 depicts the head of the

victim, in frontal view, against a clean, white porcelain background.

The left eye, left temple, and upper left side of the head and skull

are simply missing. There is little blood or internal structures of

the skull showing. No part of the brain is visible. There are no

autopsy marks.

Appellant objected to the admission of exhibit 5.

The objection was overruled. On appeal, the claim is made that this

ruling was error in that it was cumulative of the testimony of the

pathologist when using a model of the head and that its relevance was

outweighed by its tendency to inflame and impassion the jury against

the defendant. In Kiefer v. State (1958), 239 Ind. 103, 153 N.E.2d

899, cert. denied, 366 U.S. 914, 81 S.Ct. 1089, 6 L.Ed.2d 238 (1961),

five of six photographs of the body of the deceased admitted at trial

were admitted over objection. Three were held properly admitted as

they served to "elucidate and explain relevant oral testimony given at

the trial and they were properly admitted for the purpose of showing

fully the scene of the crime, the nature of the wounds of the victim,

and the condition of the basement immediately after the crime was

committed." Id. at 108, 153 N.E.2d at 900. Two were held improperly

admitted. They depicted the hands and instruments of the pathologist

inside the chest cavity of the deceased during an autopsy. Such

photographs were condemned because their tendency to enlighten the

jury was dubious, while their tendency to arouse sympathy for the

victim and indignation against the accused was great.

[ 556 N.E.2d 1321 ]

We conclude that exhibit 5 does not fall within the

class of those deemed inadmissible under Kiefer. The restraint of the

prosecution in presenting this photograph is apparent. It stands alone

as a close-up photograph of the head. The facial appearance is quite

normal, despite the absent portion. It is relevant on the issue of

identification. There are no signs of cutting or alteration by the

pathologists, and no instruments are present. A side view of the head

in a photograph would have been equally accurate, but would have had a

much greater tendency to prejudice the ability of the jury to make

dispassionate determinations of fact. Exhibit 5 accurately showed the

nature and extent of the deceased's wound to the head, and it

portrayed the wound in the manner least calculated to arouse sympathy

and indignation. It was not unduly gruesome or prejudicial and was

properly admitted.

V.

The defense proffered its proposed final

instruction No. 6, intended for use at the guilt-innocence stage of

the trial. The essential character of that feature of the instruction

tending to restrain deliberations to the benefit of the defense is to

be gleaned from the admonitions in the instruction that the jury

"should not be swayed by any undue demand for conviction by the State"

and that it should "put aside any consideration of public approval or

disapproval." The trial court rejected the instruction on the basis

that its subject was sufficiently covered by other instructions which

were given.

In resolving this claim, it is not necessary for us

to determine the correctness of this tendered instruction. It is

sufficient if it be determined that such instruction was covered by

other instructions. New v. State (1970), 254 Ind. 307, 259 N.E.2d 696.

Several instructions restrained the jury to a consideration of the

evidence presented at trial in determining guilt, which by necessary

intendment prohibited consideration of information and opinions from

other sources and consideration of the publicity and public interest

surrounding the trial. One of the court's instructions contained an

express prohibition against being influenced by sympathy for the

victim and prejudice against the defendant. The substance of this

defense instruction was presented to the jury in appropriate fashion

in other instructions and, therefore, there was no error in the

refusal to give it.

VI.

The defense proffered its proposed final

instruction Nos. 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12, to be given to the jury at

the guilt-innocence stage of the trial. The purpose of these

instructions was to permit the jury to find appellant guilty of the

offense of assisting a criminal, rather than murder. The trial court

refused the instructions, ruling that such offense was not a lesser

included offense of murder.

One who harbors, conceals or otherwise assists a

person who has committed a crime, while intending to hinder the

capture or punishment of such person, is guilty of assisting a

criminal. I.C. 35-44-3-2. One who knowingly or intentionally aids,

induces or causes another person to kill is guilty of murder. I.C.

35-42-1-1; I.C. 35-41-2-4. The charge here was knowingly killing a man

by shooting him. It is apparent from a comparison of the statutes that

one who aids, induces or causes another to commit murder has not

necessarily assisted any person in avoiding detection and arrest, and

that the latter is not a necessary lesser and included offense within

the former, from the statutory viewpoint. The jury was instructed that

appellant could be guilty of murder if she aided, induced or caused

others to kill, such conduct necessarily occurring during the events

leading up to and including the act of killing. The charge did not

allege conduct that would have constituted the separate offense of

assisting a criminal, and therefore assisting a criminal was not a

lesser and included offense of murder from the standpoint of the

allegations in the information. Reynolds v. State (1984), Ind., 460

N.E.2d 506. Since the proposed lesser included offense was not

included within the charge, it did not qualify for inclusion in a jury

instruction as an alternative to murder, despite

[ 556 N.E.2d 1322 ]

the fact that there was abundant evidence at trial

of her conduct and state of mind when helping Buchanan and Music after

the death of Thacker which would have supported a conviction for such

proposed offense.

In Beck v. Alabama,447 U.S. 625, 100 S.Ct. 2382, 65

L.Ed.2d 392 (1980), the United States Supreme Court held that, as a

matter of due process, the benefit of lesser included offense law must

be extended to those facing capital charges on the same basis that it

is extended to those facing non-capital charges. Here, the offense of

assisting a criminal is not a lesser included offense of the charged

crime of murder, and this same legal conclusion would follow if this

were not a capital case. Appellant testified that she was not involved

in the planning and plotting to kill Thacker and denied helping

Buchanan and Music later with knowledge of the fact that they had shot

him. This testimony created a conflict for resolution by the trier of

fact. It did not require the proposed defense instructions on the

lesser uncharged crime of assisting a criminal as a matter of due

process.

VII.

Appellant was charged outright by information with

the unlawful shooting and killing of Thacker at a particular point

along a roadway. She filed a notice of alibi, asserting that she was

in her home at the time of the death. The State did not file a

response, and the evidence at trial, without exception, placed her in

her home at the time of his shooting and death on the roadway. She was

convicted through final jury instruction Nos. 3 and 4 upon the theory

that she aided, induced or caused other persons to commit the offense.

Appellant claims that the charge did not provide her with due notice

of the nature of the accusation against her in violation of the Sixth

Amendment and Article 1, § 13 of the Indiana Constitution.

In the former statute defining accessory after the

fact, it was declared that "[e]very person who shall aid or abet in

the commission of a felony, ... or procure a felony to be committed,

may be charged[,] ... tried and convicted in the same manner as if he

were a principal... ." I.C. 35-1-29-1 (Burns 1975). This statute was

repealed by the time of appellant's offense and replaced by I.C.

35-41-2-4, which declares that "[a] person who knowingly or

intentionally aids, induces, or causes another person to commit an

offense commits that offense... ." Aiding, inducing or causing an

offense is not a separate offense under this newer statute, but is, in

fact, the basis of liability for the underlying offense, in this case,

murder. Hammers v. State (1987), Ind., 502 N.E.2d 1339. Despite the

omission of any reference to the manner of bringing a charge in this

newer statute, this Court has continued to sanction bringing the

charge as though the accused were a principal, Harris v. State (1981),

Ind., 425 N.E.2d 154, and has not required the charging instrument to

contain special references to conduct, remote in place or time from

the place or time of the actual consummation of the crime, which one

might deem to be acts of aiding, inducing, or causing the crime,

rather than acts of actual participation. It has, however, become

common practice to allege specific acts of aiding and inducing in the

charging instrument. See Whitehead v. State (1986), Ind., 500 N.E.2d

149. In Lawson v. State (1980), 274 Ind. 419, 412 N.E.2d 759, cert.

denied, 452 U.S. 919, 101 S.Ct. 3057, 69 L.Ed.2d 424 (1981), this

Court sought out and found that an express notice was given the

accused of the prosecutor's intention to proceed upon a theory of

accessory liability in the prosecutor's response to the defendant's

notice of alibi. Here, by contrast, there was no such notice. There

was, however, an equivalent thereof in the pre-trial proceedings when

appellant became aware that others were charged with the same crime,

when the trial judge at arraignment read to appellant the murder

statute and I.C. 35-41-2-4, the aiding and causing statute, and when,

during voir dire examination of the jury, the State amended the death

count to include an allegation that appellant had hired Buchanan to

commit the murder. These events placed appellant on notice of the

prosecution's intent to proceed on a theory

[ 556 N.E.2d 1323 ]

sanctioned by I.C. 35-41-2-4. There was therefore

no error in giving instruction Nos. 3 and 4 on that theory.

VIII.

Appellant next claims that the evidence of guilt

was wholly insufficient to support the jury verdict. In determining

this question, we do not weigh the evidence nor resolve questions of

credibility, but look to the evidence and reasonable inferences

therefrom which support the verdict. Smith v. State (1970), 254 Ind.

401, 260 N.E.2d 558. The conviction will be affirmed if, from that

viewpoint, there is evidence of probative value from which a

reasonable trier of fact could infer that appellant was guilty beyond

a reasonable doubt. Bruce v. State (1978), 268 Ind. 180, 375 N.E.2d

1042, cert. denied, 439 U.S. 988, 99 S.Ct. 586, 58 L.Ed.2d 662.

The charge was founded on the legal rule supplied

by I.C. 35-41-2-4, that one who causes another to commit an offense is

guilty of committing that offense. Such rule imposes a form of

vicarious liability, rather than liability based upon physical

participation in the direct and immediate acts which constitute the

offense itself. Kappos v. State (1984), Ind., 465 N.E.2d 1092. In

order to prove the crime of murder upon the basis of this legal

theory, the State would have to prove that:

(1) appellant;

(2) knowingly or intentionally;

(3) Induced;

(4) Another person;

(5) To kill a human being.

The evidence summarized at the beginning of this

opinion was provided by appellant's sister, Busick, and Buchanan, Hart

and Music, all of whom testified pursuant to plea agreements or

expectation of leniency. Their testimony provided the basis for the

trier of fact to infer to a moral certainty beyond a reasonable doubt

that appellant created the plan to kill, recruited Buchanan, Hart and

Music to execute the plan, offered them incentives to execute the

plan, and that the three agreed to execute the plan and did so.

Appellant first offered Buchanan money to find

someone to kill Thacker, and when he failed, directly offered him

money to do it. Buchanan agreed. He was present and assisted in the

ambush and also took the victim's wallet. Buchanan was the boyfriend

of appellant's younger sister, Busick.

Hart was asked by Buchanan to kill Thacker, and

Hart was present when appellant offered to pay both him and Buchanan.

Hart did not reply verbally, but showed his agreement by immediately

procuring a shotgun with which to commit the killing. Hart drove the

three to the crime scene, helped place the log across the road, and

stood by as the ambush occurred. Hart was a friend of Buchanan.

Music was asked by appellant on October 31,

November 1, and the night of the crime, November 2, to kill Thacker.

On the first occasion, he refused. On the second occasion, he was in

appellant's trailer with Buchanan and Hart. He at first refused, then

appellant taunted him, calling him and the others "chicken shit," and

then he and the others agreed. They left the trailer, Hart and Music

armed, and waited up the road for Thacker to drive by. When he did,

they raised their weapons, but Buchanan said for them not to fire, and

they did not. Music was appellant's cousin.

The next night, the same three were gathered in

appellant's trailer and she again asked them to kill Thacker and

cajoled them as previously. She then told Music that Thacker had

killed her first husband, Huff, who had been one of Music's best

friends. This angered Music, and he agreed again to participate in the

plan. The three men again departed the trailer, went about 500 feet up

the road, and hid at the chosen spot. They blocked the road with a log

and waited. Thacker came along, stopped, got out and moved the log.

Music alone was armed, and he actually shot Thacker as the other two

watched. Appellant had previously chosen the type of shotgun shells to

be used in the killing, bought them, and given them to Buchanan. She

likewise had chosen the location along the road at which the trap was

to be

[ 556 N.E.2d 1324 ]

sprung. The character of this evidence is such that

from it, a reasonable trier of fact could conclude to a moral

certainty beyond a reasonable doubt, that appellant knowingly and

intentionally, through a mixture of devices, aided, induced and caused

the three men to ambush, shoot and kill her husband.

Appellant challenged the four main witnesses

against her, citing several examples of their testimony which are

argued as demonstrative of their inherently improbable and coerced

nature. All testified pursuant to plea agreements or with an

expectation of leniency. All admitted having previously lied, having

previously made inconsistent statements, and having been drug abusers.

Busick testified that she had become pregnant by both Huff and Thacker

and that she had previously made false statements, and her testimony

supplied the basis for the inference that she was very gullible and

under the control of a particular police officer for whom she had

served as an informant. Busick was confused about the dates of several

of the events surrounding the crime. Similar challenges are made

against the witnesses Buchanan, Hart and Music.

In Rodgers v. State (1981), Ind., 422 N.E.2d 1211,

this Court through Justice Hunter wrote:

Defendant's contention strikes directly at the

credibility of the witnesses, a matter which with rare exceptions is

solely the province of the jury. Only when this Court has confronted

"inherently improbable" testimony, or coerced, equivocal, wholly

uncorroborated testimony of "incredible dubiosity," have we impinged

on a jury's responsibility to judge the credibility of witnesses.

Id. at 1213 (citations omitted). The factors cited

by appellant in her brief certainly diminish the credibility of the

prosecution witnesses and the weight which one might reasonably give

their testimony. However, at its core, the body of testimony of these

witnesses is in accord, and not contrary to natural laws or human

experience. We find the evidence sufficient to convict.

IX.

Appellant next claims that the evidence serving to

support the penalty of death was insufficient.

A.

Count II of the information specified that the

death penalty was being sought upon the basis of I.C. 35-50-2-9(b)(3),

which provides:

(b) The aggravating circumstances are as follows:

....

(3) The defendant committed the murder by lying in

wait.

Appellant was convicted of murder. This conviction

placed her in a class subject to the death penalty. I.C. 35-50-2-9(a).

This class includes those who, like appellant, are guilty of murder as

an accessory or accomplice. Brewer v. State (1981), 275 Ind. 338, 417

N.E.2d 889, cert. denied, 458 U.S. 1122, 102 S.Ct. 3510, 73 L.Ed.2d

1384, reh'g denied, 458 U.S. 1132, 103 S.Ct. 18, 73 L.Ed.2d 1403

(1982). The finding of the trial judge that appellant committed this

murder by lying in wait, an aggravating circumstance enumerated in the

death sentence statute, placed her in a sub-class of those convicted

of murder, namely, those convicted of murder and subject to the death

sentencing process involving the weighing of aggravating and

mitigating circumstances. This Court recently held that this sub-class

includes those who intentionally kill when acting as an accomplice or

accessory in one of the enumerated felonies in I.C. 35-50-2-9(b)(1).

Lowery v. State (1989), Ind., 547 N.E.2d 1046 (DeBruler, J.,

concurring and dissenting). The question presented here is whether

appellant was properly placed in this sub-class by reason of the

aggravator provided for in I.C. 35-50-2-9(b)(3).

The special elements constituting a murder by lying

in wait are watching, waiting and concealment from the person killed

with the intent to kill or inflict bodily injury upon that person.

Davis v. State (1985), Ind., 477 N.E.2d 889, cert. denied, 474 U.S.

1014, 106 S.Ct. 546, 88 L.Ed.2d 475. In such a crime, there is

considerable time

[ 556 N.E.2d 1325 ]

expended in planning, stealth and anticipation of

the appearance of the victim while poised and ready to commit an act

of killing. Then, when the preparatory steps of the plan have been

taken and the victim arrives and is presented with a diminished

capacity to employ defenses, the final choice in the reality of the

moment is made to act and kill. This aggravating circumstance serves

to identify the mind undeterred by contemplation of an ultimate act of

violence against a human being and, of equal importance, the mind

capable of choosing to commit that act upon the appearance of the

victim. We therefore construe this statutory aggravator as intending

to identify as deserving consideration for the penalty of death those

who engage in conduct constituting watching, waiting and concealment

with the intent to kill, and then choosing to participate in the

ambush upon the arrival of the intended victim.

The evidence here is clear and uncontradicted in

placing appellant inside her trailer at the moment of the killing. She

remained in the trailer when the three young men left. They stationed

themselves in the woods along the road at a point 500 feet from the

trailer, where they watched, waited and concealed themselves from the

victim with the intent to kill him, and when he arrived at the spot,

they acted on their intention and did kill him. While appellant

planned and desired that the crime be committed by lying in wait, and

caused others to commit the crime as planned, she was not at the crime

scene and did not make that required choice to participate in the

attack upon the arrival of the victim. Consequently, while her conduct

warrants a conviction for murder as an accomplice or accessory, it

does not place her in a category subject to the death sentencing

process through the aggravating circumstance of committing a murder by

lying in wait. The evidence of this statutory aggravator, properly

construed, is insufficient.

B.

Count II of the information also called for the

sentence of death to be given on the basis of the aggravating

circumstance set forth in I.C. 35-50-2-9(b)(5), which provides:

(b) The aggravating circumstances are as follows:

....

(5) The defendant committed the murder by hiring

another person to kill.

The trial court found that this aggravating

circumstance was proved beyond a reasonable doubt. The information

alleged that appellant committed the murder by hiring Buchanan to kill

Thacker.

The evidence demonstrates that appellant procured

the killing of her husband by three persons: Buchanan, Hart and Music.

Buchanan testified at trial and described the first relevant contact

with appellant which occurred several weeks before the killing:

Q. Just you and Lois and what did she say?

A. She just come up to me and asked me if I know

[sic] anybody would kill her husband.

Buchanan made no response to appellant's first

inquiry. Buchanan described a later second contact:

Q. What did she — what did the rest of the

conversation?

A. She said If I found somebody that she'd pay them

and she would buy a rig for me to drive.

Q. Do you remember telling her how much it cost?

A. I said about eighty thousand dollars ($80,000).

Buchanan then described a meeting in a city park

with appellant. Hart was then present. It took place on November 1,

the day before the killing.

Q. And what did she say?

A. She asked me if I'd do it. She'd give me and

James Hart a thousand dollars each if we'd do it.

Q. So you — what did you say when she offered you

the thousand dollars each?

Q. And who was responding to her?

A. Me and James.

[ 556 N.E.2d 1326 ]

Buchanan agreed verbally. At the close of this

meeting, Hart went off and got a gun from his brother to commit the

killing. At trial, Hart testified about this meeting in the following

manner:

Q. Now if D.J. [Buchanan] says you were offered a thousand dollars to

kill John Thacker, would that be right or wrong?

A. I hear[d] Lois talking about money but as far as

her coming to me and saying, "I'll give you money to kill him", no.

Q. Did D.J. ever offer you money to help?

A. No.

That night, Buchanan, Hart and Music gathered at

appellant's trailer. There is no evidence at all that Music was ever

offered money or benefit to kill, or that money or compensation was

mentioned at all on this occasion. When asked by appellant to help,

Music, who was appellant's cousin, refused. Appellant then repeatedly

called them chicken shit and told Music that her husband, John

Thacker, had shown some interest in his girlfriend. This motivated

Music, and all three then left the trailer, agreeing to kill Thacker.

Hart and Music armed themselves and hid alongside the road at the

point of ambush. Hart and Music raised their weapons when the victim

drove by, but Buchanan said not to shoot, and they did not. The three

then agreed to tell appellant that there had been a car following the

victim and that this was the reason they did not shoot.

The next night, the three again gathered at

appellant's trailer. No mention of money or compensation was made.

Appellant hazed the three again, calling them chicken shit. She then

took Music aside and told him that her husband, John Thacker, had

killed her first husband, Huff. Huff had been a good friend of Music,

and the new information enraged him, and he agreed to shoot Thacker.

The three men left again. Buchanan said that he did not have the

courage to shoot Thacker. This time, only Music was armed. The three

concealed themselves along the road. When Thacker arrived, Music shot

him once from concealment and a second time at close range as he lay

in the roadway.

In Norton v. State (1980), 273 Ind. 635, 408 N.E.2d

514, the Court interpreted a prior version of the homicide statute

which proscribed the killing with purpose and malice "by a person

hired to kill." I.C. 35-13-4-1 (Burns 1975). There, this Court

concluded that a murder for hire has been committed when one offers or

promises compensation to another for performing a killing, and the

other person commits the murder pursuant to or in response to this

offer or promise.

This aggravating circumstance is applicable when

the defendant has been successful in locating and persuading another

person to kill for pecuniary gain. The will, capacity and facility for

doing so, identifies the person deemed here by legislative intent to

be deserving of consideration for the death sentence.

Not one, but three young men participated in this

homicide. Appellant's representations to each was different, and their

motivations were different. Buchanan was offered money and agreed, yet

he was reluctant until repeatedly called a coward by appellant, his

girlfriend's older sister. Thus, with this mixed motive, he led the

group up the road on the first night. He was not armed and, when the

victim appeared, he called for the others not to shoot. The next

night, he declared that he did not have the courage to kill the

victim; however, when again challenged as a coward by appellant, he

agreed to go, but again did not arm himself.

The evidence that Hart engaged in either the first

aborted ambush or the second successful one in expectation of

compensation is insufficient. He was a long-time friend of Buchanan

and was first asked by Buchanan to help. Buchanan did not offer him

money. The offers of money to both was made by appellant to Buchanan

in Hart's presence. Buchanan accepted the offer verbally, and Hart

indicated his agreement through his conduct in advancement of the

plan. He did not respond verbally to this offer. He testified as a

witness for the prosecution that the conversation

[ 556 N.E.2d 1327 ]

created no expectation in him that he would receive

any money and that he participated out of fear. On the occasion of the

fatal shooting, he went to the scene and participated in preparing it

to trap the victim, but did not arm himself.

The evidence that Music, the triggerman, was

motivated because of an offer of compensation from appellant is

non-existent. It is clear that he led the final ambush and was then

motivated by appellant's hazing and his animosity toward John Thacker,

the victim.

It is evident that we would be stretching the

language defining this aggravating circumstance beyond its intended

meaning if we were to find the evidence sufficient to support the

allegation that appellant committed this murder by hiring Buchanan or

either of the other two to kill. On this analysis, we find the

evidence of this second aggravating circumstance insufficient.

The judgment of conviction is affirmed. The

sentence of death is vacated. This cause is remanded with instructions

to enter the maximum prison sentence for murder provided for by law.

Cooper v. State (1989), Ind., 540 N.E.2d 1216.

SHEPARD, C.J., and DICKSON, J., concur.

GIVAN, J., dissents with separate opinion.

PIVARNIK, J., dissents and joins in the opinion of

GIVAN, J.

GIVAN, Justice, dissenting.

I respectfully dissent from the majority opinion in

the setting aside of the death penalty. The first reason given by the

majority opinion is that there is insufficient proof that appellant

was guilty of lying in wait to kill the decedent.

The majority cites the fact that appellant was in

her trailer during the attack. However, the majority decision on this

question is diametrically opposed to the correct findings in the early

part of the opinion, which correctly hold that it is not necessary for

appellant to have taken part directly in the murder as long as she

planned and directed the execution of the same.

It is unnecessary for this dissent to reiterate the

authority for that proposition of law as it is amply contained in the

majority opinion. That evidence alone is sufficient to sustain the

death penalty. However, the majority proceeds to find that there is no

evidence that appellant hired the actual perpetrators of the murder

but simply persuaded them to so act.

As observed by the majority opinion, there is

direct evidence that Buchanan was offered money to accomplish the

killing. There is ample circumstantial evidence in this record from

which the jury could have determined that all three men understood

that there was to be compensation for the killing. For the majority

now to hold this evidence to be insufficient is purely a matter of

weighing the facts which was the exclusive prerogative of the jury.

Even if it is to be conceded that there is

insufficient evidence that money was to be paid to the perpetrators

the evidence of lying in wait to commit the killing is without

contradiction and correctly set forth in the majority opinion. I

cannot join in the rationalization of the majority to set aside the

death penalty.

I would affirm the trial court in all things.

PIVARNIK, J., concurs.