|

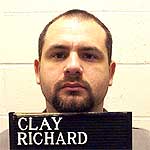

The Case of Richard Clay

RickDClay.com

Richard (Rick) Clay has been on Missouri's death row

since September 1995, condemned to die for a crime he did not commit. In

2001, he was granted a new trial due to a district court decision that

his original conviction was based on perjured testimony and concealment

of evidence favorable to his defense.

However, the decision was overruled a year later by

the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals. His sentence has been disputed for

over a decade.

But undeniable is the fact that Clay was sentenced

based entirely on questionable circumstantial evidence; absolutely

nothing puts him at the scene of the crime he's accused of committing.

The prosecution based its case on the word of two people who had the

most motive to kill and admittedly planned to do so.

One of the two accusers, Chuck Sanders, was

originally charged with first degree murder in the case, and openly

called a liar by prosecutors after it was revealed he disposed of a box

of the same bullets used in the murder. Weeks later, he was their star

witness.

The second "witness," the wife of the victim in the

case, was found with gunpowder residue on her hands in the hours after

the crime and had written a check to Sanders to kill her husband. No

evidence of any payment to Clay was ever found.

Finally, Clay was convicted by a former attorney who,

in ten years as a state and county prosecutor, has had 50% of his

capital punishment convictions overturned. Even judges admit Kenny

Hulshof "too readily embellished arguments with his own opinions, or

with facts outside the court record."

Taken together, it inevitably leads one to question

how Clay can be sentenced to death based on so many questions and so

little evidence. Clay was the only one near the murder scene that night

with a (nonviolent) criminal record, and coupled his service in the US

Marine Corps and his proficiency with the use of a firearm, his history

was a convenient target for prosecutors.

The Death Penalty: Career Builder

In 2007, Curtis McCarty, who had been sentenced in

Oklahoma to die three times and spent 21 years on death row for a crime

he did not commit, was released after a District Court Judge ruled that

the case against McCarty was tainted by the questionable testimony of

former police chemist. DNA testing also showed that another person raped

the victim. While now free, how does the state of Oklahoma give McCarty

back 21 years of his life? They can’t.

But it is cases like McCarty’s that should give even

the staunchest capital punishment proponents pause.

While it’s impossible to identify how many innocent

people have been put to death by capital punishment, four investigations

in as many years indicate that it’s probable – including Larry Griffin.

Griffin, sentenced to death in Missouri a 1980 drive-by shooting due

mainly to testimony from single eyewitness, was executed before a police

officer divulged that he gave false testimony implicating Griffin. In

addition, it was later revealed that a second victim injured in the

drive-by -- never interviewed by defense or prosecuting attorneys --

claimed the eyewitness wasn’t even there.

According to Northwestern University School of Law's

Centre on Wrongful Convictions (CWC), at least 39 executions have been

carried out in the United States in face of compelling evidence of

innocence or serious doubt about guilt. While innocence has not been

proven in any specific case, there is no reasonable doubt that some of

the executed prisoners were innocent.

In addition, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU)

has documented 129 death-row inmates who, since 1973, have been

exonerated and freed before their executions.

How does this happen?

Is it so idealistic to believe people who are

entrusted with the lives and liberties of others should prevent

injustices which jeopardize the very things they are sworn to protect?

If they stand by and don't act on the information they have, aren’t they

just as guilty of criminal activity as those who recklessly and

maliciously take other people's lives?

In 2006, three Lacrosse players from Duke University accused of

sexual assault by an overzealous prosecutor -- Mike Nifong. In order to

win re-election, he was willing to send three men to prison for life

despite his knowledge of DNA reports proving these men were in fact

innocent of the crime. Nifong was later disbarred by a panel that

unanimously found him guilty of fraud, dishonesty, deceit or

misrepresentation. But what the case leads one to believe is that its

improbable to think it was the first time Nifong or any other prosecutor

has withheld evidence favorable to defendants to enhance his personal

motives. If not for the overwhemling attention and scrutiny placed on

the case, Nifong's tactics may have gone unnoticed.

In the case of Richard Clay, similar ethical questions about the

motives of the prosecutors have been raised.

But this shouldn’t come as a shock for those who are familiar with

Hulshof. According to a June 2008 Associated Press investigation,

Hulshof handled 31 murder cases in 10 years as a state and county

prosecutor, and won death penalty conviction in eight of those trials.

The AP review of court dockets, state and federal appellate decisions

and other legal records shows that in four cases, prosecutorial errors

by Hulshof led to death sentence reversals.

Another accused murderer won acquittal by a new jury at a second

trial after his Hulshof-prosecuted conviction was rejected on appeal.

A sixth defendant sentenced to life in prison without parole briefly

won his freedom when a federal judge tossed out the conviction, although

it was later restored.

Finally, a seventh murder conviction, that of Josh Kezer – who was

also convicted almost entirely on the testimony of one witness – was

reopened after an interview with Scott City police “surfaced” which

showed that witness had previously named another person. Kezer's

appellate attorney said that interview was never shared with his

original defense attorney.

For those keeping track, a majority of Hulshof's death penalty

convictions have been either completely reversed or called into question

due to prosecutoral error or some degree of apparent misconduct. Another

two life sentences were either thrown out, or are about to be.

This is staggering.

“Critics say Hulshof's record reflects a lawyer who crossed the line

from zealous representative of the people to a politically ambitious

prosecutor willing to bend the rules for the sake of a conviction,” adds

the Southeast Missourian newspaper.

That only begs the question: doesn’t Hulshof’s track record make it

possible – if not probable – that this record of "bending the rules" led

to a conviction in the case of Richard Clay?

Here are the facts that lead many to believe that another innocent

man was condemned to die by the state of Missouri:

-

Richard Clay was sentenced to death based entirely on circumstantial

evidence. No physical evidence linking Clay to the murder of Randy

Martindale was ever found. Hair fibers and fingerprints taken from the

crime scene did not match Clay or his clothes. The murder weapon was

never found.

-

The State relied primarily on the testimony of two people who 1) not

only admitted to plotting to kill Randy Martindale -- his wife Stacy and

her lover Chuck Sanders -- but 2) two people who had the most motive to

commit the crime.

-

Gunshot residue was actually found on the hands of Stacy Martindale,

and the State’s own expert witness testified that it was possible she

fired the handgun.

-

Crucial to the prosecution’s case was Sanders and Stacy Martindale’s

claim that Clay killed Randy Martindale and escaped alone in Stacy’s

car. However several witnesses, including in an unsigned affidavit by

the officer in pursuit of the vehicle, say they saw two people in the

car. If so, Sanders' testimony collapses and Richard Clay is exonerated.

-

In fact, when the pursuing officer arrived on the scene seconds

after after Stacey's vehicle stops, both car doors were reported open.

Yet the State claims Clay drove the vehicle alone, opened both doors to

throw off police, and fled on foot.

-

The State claims a crucial piece of evidence linking Clay to the

crime was a bullet casing of the same caliber and gun type used to kill

Martindale. The casing was found “150-200 yards” away from the closest

footprints the prosecution claim were Clay’s.

-

Clay’s pretrial criminal record made him a target for prosecutors

Hulshof and Bock. His pending trial for drug possession and resisting

would diminish his credibility in the eyes of jury members, and his

Marine Corps training made him the most capable of the suspects in the

use of a handgun.

-

Numerous witnesses whose accounts corroborate Clay’s came forward

after his trial, but only because the court-appointed defense team

failed to investigate and provide subpoenas for their testimony.

-

The first officer on the scene that night offered to sign an

affidavit claiming that he would have testified to details beneficial to

Clay’s defense, but it went unsigned because he worried the document

would undermine his working relationship with the New Madrid County

prosecutor, Riley Bock.

Details of Clay's Case

In May 1994 Rick Clay was arrested for the murder of Randy

Martindale who was shot to death in his estranged wife's home. Clay was

found guilty in June 1995 in Fulton, Missouri and sentenced to death.

The victim’s wife, Stacy Martindale, was sentenced to fifteen years in

prison. Stacey’s boyfriend at the time, Chuck Sanders, was given five

years probation for his role in the murder. Nearly all physical evidence

and motive that exists in the case points to Stacy Martindale, including

gunpowder residue found on Stacey’s hand in the hours after the crime.

In 1990, Chuck Sanders and Stacy Martindale both worked for Media

Press in Sikeston, Missouri where they soon became romantically involved

in what was described as an on-again-off-affair, lasting until the time

of Randy's murder. During this time period, Stacy became pregnant with

her second child and told Chuck that he was the father of the child.

She would often come by Sanders’ residence in Sikeston to let him

see the child. During these visits she would show Sanders bruises on her

neck and shoulders and attributed them to Randy's physical abuse.

Sanders, angered by the thought of Stacey’s abuse at the hands of Randy

Martindale, would often confide in he what he would do to Randy for his

abuse. Martindale would calm Chuck down and often tell him she would

divorce her husband and that they could be together as a family. As time

passed, and the Stacey’s allegations of abuse by Randy Martindale

continued, Sanders testified that sometime in the spring of 1994, a fed

up Stacey Martindale asked him to kill her husband for ten thousand

dollars.

Sanders, who was initially receptive to the prospect of killing

Stacey’s husband, said during testimony that in the few months leading

up to the murder that he and Stacey talked several times on how to kill

him. Soon thereafter, Sanders confided in close friends of Rick Clay and

Darryl Jones about his conversations with Stacey. When questioned about

his conversation with Clay, Sanders said that “I asked Ricky what he

would think if I killed Randy.”

Clay’s response was that it “would be a stupid thing to do,” adding

during testimony that nobody took remarks like that seriously, that in

1993, most friends of Clay and Sanders were often taking methamphetamine

and drinking and spouting off threats.

In early 1993, Clay – a professed drug distributor at the time –

borrowed Sanders' car to deliver some Meth, and carried with him drug

paraphernalia such as vials, scales, and baggies.

Some three blocks from where he and Chuck shared a house, a Sikeston

Police Officer made a routine traffic stop. Clay, panicking, ran from

the car with the bag containing the illicit items. Soon realizing he was

cornered, Clay then hid the case and surrendered.

After extensive questioning, Clay said he ran from police because he

did not have a valid driver’s license. However, police officers later

searching the area and found the case and its illegal contents.

Clay was charged with the possession of meth, drug paraphernalia,

and unlawful use of a weapon.

After posting bond, Clay admits he continued to sell methamphetamine

to pay for the attorney he attained that he hoped would keep him out of

prison. As of May 1994, Clay’s case had yet to go to trial. He again

borrowed Sanders’ car while he was at work to run errands for then-girlfriend

Candy Richmond. It was Richmond’s birthday and some friends were meeting

at a local club in Sikeston called the Double Nickel (also known as JD’s)

to celebrate.

After completing their errands, Clay dropped off Richmond at a

mutual friend’s house, adding he would pick up Sanders from work and

meet them at the club. After arriving at Sanders place of employment – a

Radio Shack in Sikeston, MO - Sanders informed Clay that they had to

wait a few minutes, adding that Stacy Martindale was stopping by to talk

to Sanders.

When Martindale arrived, Clay got out of the car andleft Sanders and

Martindale to talk alone, returning inside Radio Shack to talk to

another friend, Mike Frederick, who also worked at the store.

After Clay and Frederick briefly discussed plans of going to

Hardee's to pick something up to eat, Sanders and Martindale came into

the store. Clay testified that he could tell Sanders and Martindale had

been arguing – arguments had become more frequent between the two,

according to Clay.

Sanders then confided in Clay that he was angry because Martindale

and her husband Randy had dinner together the night before. When Clay

told Sanders that he and Frederick were hungry and going to a nearby

Hardee's to eat, Sanders suggested that Clay should ride with Martindale,

and explain Sander’s feelings for her. Clay agreed to the ride from

Martindale.

After a very short trip to Hardee's (visible from Radio Shack),

ordering food, and waiting to pay, Sanders pulled behind Clay and

Martindale. Clay got his food, got out of the car to speak with Sanders,

and Stacy drove off. When Sanders asked Clay where she was going, Clay

said Martindale told him she had a girl's night out. Sanders, upset by

the Martindale’s decision to leave, asked if Clay explained to her how

he felt. Clay told Sanders: “I'm not sure how you feel.”

Deposition of Chuck Sanders April 24, 1994

Present Attorney Bob Wolfrum - Attorney for Rick Clay

Prosecutors Riley Bock & Hulshoff.

Page 61 thru 71 (Starting at Line 7 on Page 61)

Conversation between Stacy Martindale and Chuck Sanders at Radio

Shack - May 19,

1994

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) What was the conversation there by your car?

A: (Chuck Sanders) She was at her last rope you know she was down to

the end of her rope. She really needed this done, if I wasn't going to

do it. Should I continue? If I wasn't going to it, to quit stringing her

along, you know quit telling her that I would think about it, or that I

didn't want to hear anything about it, to give her a definite yes or no

answer. And you know I don't remember her exact words, but I think she

called my manhood into question and said if I didn't do it I wasn't much

of a man taking care of her and Brett or something like that.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Okay and you, did you just say there was a fairly

heated discussion?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Yeah, that was pretty heated. She was insulting

me.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Was that something Rick or Mike Frederick saw?

A: (Chuck Sanders) I don't know if they would have seen it or not. I

would think that they probably recognized by body posture I was agitated.

If they looked outside they may have seen it, yeah

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Is the front of Radio shack pretty much a glass

front.?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Yes, it's a glass front.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Okay and it was close to the time this Frederick's

would have been closing the store?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Yes.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Anything else that she said?

A: (Chuck Sanders) She said if I wasn't going to do it, she would

get somebody who would, and she intimated that she was gonna go talk to

Rick. And I told her that nobody else was gonna do anything for her, and

that you know to leave Rick alone leave him out of it and that I

wouldn't have anything to do with it. She asked what she was suppose to

do and I told her what my advice was.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) And what was your advice?

A: (Chuck Sanders) That if she is a battered spouse, she needed to

get herself a gun and when he beat her, she could kill him and then she

could claim spousal abuse.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) What was her response to that?

A: (Chuck Sanders) I don't remember if she had a verbal response. It

was, I don't think she was very happy with the idea that I would not

help her.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Okay. Did she say to you why she didn't want to do

that?

A: (Chuck Sanders) NO, no she didn't. I don't recall her bringing up

any specific objections.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Okay. Um what happened next? You said she said that

if you wouldn't do it she'd talk to somebody else and you said intimated

that she was gonna talk to Rick?

A: (Chuck Sanders) I believe so. I'm not sure if she said Rick's

name, I can't, she just said that I was gonna go talk to Rick, but that

was an earlier synopsis, so I linked the two of them together in my mind.

I think by that time she knew that I had talked about it.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) And at that point was Rick still in the store?

A: (Chuck Sanders) He was inside, yes.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Okay what happened next?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Um, I got in my car and drove up to the front of

the Radio Shack. We were, I was parked in the parking lot, I don't

remember, but I'm not sure the distance from the front of Radio Shack,

so I pulled right up in front of the store. She got in her car and

pulled up, we both walked in the store. Mike was closing, and the

quicker that, you know, the more I could help him, the quicker, he could

close, so I was going to help him close, and I told Rick that, you know,

she would not listen to me, she didn't understand me and asked if he

would go and try to make my position plain to Stacy

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Was he, prior to that point, was he gonna go with

her to your knowledge?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Oh, no.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Okay and you're saying it was your request, that

you requested that he go with her?

A: (Chuck Sanders) I requested that he talk to her, yes.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Okay. And tell her your position?

A: (Chuck Sanders) About where I stood with her, about everything,

you know, that I, I wanted him to make it plain to her that I couldn't

get myself in that kind of position.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Anything else that you told him at that point?

A: (Chuck Sanders) I don't recall whose suggestion it was that we go

to Hardee's and eat. It may have been Mike's or Rick's. I don't think it

was mine. Could have even been Stacy's. And so I think either I said or

Mike said well Rick why don't you run over there with Stacy and I had to

change clothes and I'd be right behind them and we go eat at Hardees,

and I figured that would give him a chance for Rick to tell her how I

felt.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Up to the point had you made it clear to Rick Clay

that it was your intention that Randy Martindale not be killed through

any act on your part?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Yes.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Had you ever asked him to kill Randy Martindale?

A: (Chuck Sanders) No.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) From what you have said to him, had you made it

clear to him that it was not your desire that Randy Martindale be killed?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Yes, I believe he felt that I took his advice,

that it would be stupid to have anything to do with it.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) So, he and Stacy rode to Hardee's?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Yes.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) And, what did you do?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Um , I went in the back, I had on my work clothes

my they were dressy clothes, so I decided to change into jeans and by

that time Mike had reports ran and he locked up the store, turned on the

alarm and he took his van and I took my car over to Hardee's.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Okay. How long after Rick and Stacy had left would

it have been that you made it to Hardee's

A: (Chuck Sanders) Maybe 10 minutes.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Okay. Did you know about any plans that Rick had

for the evening?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Yes Rick was going to a birthday party for his

present girlfriend.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Okay. Okay, once you arrived at Hardee's what

happened?

A: (Chuck Sanders) I drive in the front parking lot which is the

parking lot that faces Wal-Mart, and drove around the parking lot and

Stacy wasn't there, so there was a little road by a cemetery that goes

around, you can go out on it to get to the other parking lot of Hardee's,

so I drove around there and as I drove in that parking lot I saw Stacy's

car pulling through the drive thru from the highway.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Okay, what did you do next?

A: (Chuck Sanders) I pulled up next to her and talked to Rick about

ordering food. They had decided to order food through the drive-thru,

and I didn't remember if I told him what Mike wanted or if he already

found out from Mike what he wanted, but he stayed in Stacy's car and

ordered his and Mike's food and I made a little loop and pulled in

behind him, and pulled through the drive thru behind them to order my

food

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Okay, what happened next?

A: (Chuck Sanders) As I was at the window waiting for my food, Stacy

let Rick out of the car and left, and Rick got in Mike's van and gave

him his food.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) And what did Rick do then?

A: (Chuck Sanders) He started eating his food then and I pulled out

through the drive thru with my food and up beside and Rick got out of

Mike's van and got in my car.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) And when Rick got in your car, did you all have a

conversation?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Yeah, because I was kind of upset because she had

left without saying goodbye. There didn't seem to be any kind of closure

or resolution to the conflict and Rick said that he tried to make plain

to her my position, and he said that maybe he hadn't understood what my

position was with her, you know, if I wanted to carry on the

relationship or what. I got a little bit miffed with Rick, you know,

because I wanted him to make everything good and right.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Did he say anything about talking to her about

killing Randy Martindale?

A: (Chuck Sanders) No he said she had to leave. The reasoning why

she rushed off is she had to go to girls night out or something like

that.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Okay. But, it was, was it your intention that he

tell her, what, you still had feelings for her, but you did not want to

get involved in anything illegal or what was your intention for him to

tell her?

A: (Chuck Sanders) No, I meant for him to get the relationship part

straight. I had made myself plain to her as far as being involved with

the killing of Randy goes. I wanted him to explain to her that I still

cared for her and wanted to see my son, but I didn't want to be badgered

anymore or I didn't want her bringing this to me anymore

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Did he say he'd said that to her?

A: (Chuck Sanders) No, he didn't say exactly what this conversation

was.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) And your estimate is their conversation could have

lasted 10 minutes?

A: (Chuck Sanders) 15 including the drive thru, at the most I would

think.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Okay. Okay. Okay, so you and Rick were together in

the car as that the whole conversation that you had with Rick that you

can remember?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Um, he asked me where I was going from there and

I told him I had to get my parents an anniversary gift, and he told me

again I already knew this but he told me again that he was having a

party for Candy at J.D's and be sure to be there, he didn't want me

going home and being mad or anything.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Had Stacy heard mention of this party?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Not that I know of. I don't recall saying

anything to her. She wasn't privy to that conversation, so.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Okay. Did she know or had she ever met candy?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Not that I know of, no.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Okay, Urn, prior to the 19th, had you ever been

present at, do you know where Rosie's is here?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Sure.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Had you ever been there present with Rick and or

Stacy?

A: (Chuck Sanders) I've been there with Rick numerous times. I don't

recall ever seeing Stacy there. I think Rick had told me that he saw her

there one night.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Do you remember when that would have been?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Months previous, I guess.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Would it have been in '94?

A: (Chuck Sanders) If so, it would have been very early '94, most

likely '93

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) In May of '94 had you been in Rosie's with Rick?

A: (Chuck Sanders) I don't remember, I believe that it's possible,

yeah.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Okay, is that a common place that you might have

stopped off for a drink if you were here?

A: (Chuck Sanders) On Sunday's, yes.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Okay. And at Wal-Mart you got a present?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Yes I got a coffee maker for my parent's

anniversary.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Did you buy anything else at Wal-Mart?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Not that I recall.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) You said you went to Tammy Chad's?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Yes.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Who is she?

A: (Chuck Sanders) She's a friend of mine. Richard Chad's younger

sister.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) Is she a girlfriend?

A: (Chuck Sanders) Just a female friend.

Q: (Bob Wolfrum) And what was your purpose in going there?

A: (Chuck Sanders) I had been there the night before. I locked my

keys in my car and had to stay over that night, and I told her that I

would come back that evening to see what she was doing, see if she

wanted to go out or whatever.

Clay's Side of the Story

Before leaving Hardee’s, Clay told Sanders he believed Sanders’s

trip to Wal-Mart was strange since it was the first time he had

mentioned it, and the original plan between the two was to go to a

friend’s house and “freshen up” before leaving for the party for

Richmond at JD’s. Clay then told Sanders to “shake off” his unresolved

confrontation with Martindale, and to come with Clay to the party.

Sanders refused. Clay then proceeded with Frederick to the home of Mark

& Jessica Green to prepare for the party. Later that evening, Sanders

arrived at the Green’s home with a female acquaintance who Clay did not

recognize, and then departed a few minutes later. Clay proceeded to ride

with Frederick to another friend’s home, Quinton Small. After visiting

Small for “a few minutes,” Clay and Frederick next went to a local bar

called Phil’s Lounge to speak with Clay’s ex-wife Karyn Clay. Upon

arriving Clay and Frederick spoke with Karyn Clay briefly, had a beer

and played pool for 30 minutes and left. Soon thereafter, Clay and

Frederick left for JD’s to meet Richmond at her party.

Arriving at JD’s, Clay discovered Richmond had not yet arrived, and

briefly spoke with her parents. Clay then approached another friend at

the bar, Kenny Haden, who told Clay he could quickly supply Clay with

methamphetamine. Clay agreed, and soon left with Frederick to meet the

supplier at a nearby Ramada Inn.

Clay arrived at the motel, and was given methamphetamine on credit

with the intention to distribute quickly. As he was leaving the motel,

Clay witnessed Chuck Sanders and Stacy Martindale arriving. Clay spoke

with both, adding he had acquired the meth but needed to sell it quickly

in order to pay back the supplier. Martindale then told Clay that she

was interested, but needed to go back to the home she still shared with

Randy Martindale to pick up cash to pay Clay. Sanders then suggested

Clay ride with he and Martindale to get the money from Martindale’s home.

Clay agreed, and all left Sikeston for Stacy’s home in New Madrid.

The three soon arrived at the Martindale home, and Stacy parked half

in and half out of the home’s carport. Martindale then entered the home

while Clay and Sanders stayed in the car. Clay testified that within a

few minutes, Randy Martindale and the couple’s two sons arrived home

after attending a baseball game. Randy Martindale and the two sons

walked by Stacy’s car where Clay and Sanders sat, and entered the home

through the carport. Shortly thereafter (minutes), Randy came back out

the carport door, and asked Clay and Sanders what they were doing. Clay

testified they told him they were waiting on Stacy and then going to a

party. Randy Martindale then told them that Stacy wasn't going anywhere

and that they better leave, then turned and went back into the house.

A few minutes later, Stacy Martindale came to the same door in the

carport and motioned for Sanders to come to the door. Sanders got out of

the car and had a brief conversation with Stacy that Clay testified he

could not hear. Sanders then returned to the car told Clay to get in the

front seat, that they were going to pick up his car and bring Stacy

Martindale’s car back to the home.

In order to get around Randy Martindale’s car, Clay said that

Sanders had to pull forward and back up repeatedly to get around Randy's

car and in the process, apparently inadvertently snagged a child's toy

from the carport.

According to Clay, as the two (Sanders and Clay) proceeded on

Dawson's road, several witnesses saw the Camaro car dragging the toy and

sparks emanating from the pavement -- including New Madrid City police

officer Claude McFerren. When McFerren passed and turned on his patrol

lights, Clay instructed Sanders to stop the car and let him out in an

attempt to escape with the methamphetamine.

Clay, realizing he couldn't afford to get caught with the drugs

since he was still facing drug charges from Scott County, Missouri and

still owed payment to the attorney who was representing him. In addition,

Clay also cites the fact that meth wasn't paid for and promised several

family members that he was through with drugs, so running “seemed like

the best thing to do” at that moment.

Clay and Sanders came to a stop on a gravel road that briefly

diverted then intersected back with Dawson road. Officer McFerren

proceeded to the other end and drove up to the car from the front.

McFerren noted and later testified that when he arrived, the car was

empty with both doors open, the engine running, and the windshield

wipers turned on. McFerren then walked toward the vehicle from the

driver’s side and turned off the McFerren said he then heard a door shut

while looking for the vehicle occupants in “the tall grass”. Clay

observed that the area McFerren was scouring had to be the driver's side

because the area east of the passenger side was a cotton field with

short, immature plants – typical for Mid May. Under cover of darkness,

Clay ran through the fields trying to work his way back to New Madrid.

Identifying a levee, Clay navigated his way down the levee road until he

spotted several cars headed directly toward him. Realizing that flood

water prevented any potential escape path, Clay retreated to the

confines of a heavily wooded area, hoping the area would be clear soon.

When daylight came, Clay said that he could see police looking up

and down the levee, and a helicopter flying overhead. Concerned with the

apparent extent of the police search, Clay reasoned that Martindale had

told her husband about the drugs, who in turn told police that Clay and

Sanders had stolen the car, or that Sanders had gotten caught and told

them that Clay ran because of the drugs he possessed and his pending

charges in Scott County.

Shortly thereafter, believing that the area was clear and police had

moved on, Clay exited the woods but was soon spotted by a plain clothes

police officer who pointed his gun and told Clay he was under arrest.

Instinctively, Clay says he ran back into the woods, and tossed the

methamphetamine and contents of the black bag into the water, and the

bag itself onto the ground. It was there that he was arrested by three

officers and transported to New Madrid County Sheriff's Office. There,

Clay was questioned by Sgt. Dennis Overby of the New Madrid Police

Department, who told informed Clay he was being charged with the murder

of Randy Martindale. Clay told the officer that “he hadn't killed

anybody” but that he wanted to talk to an attorney, and that if the

lawyer advised him to give a statement, he would.

Questionable Evidence

Richard Clay was sentenced to death based entirely on circumstantial

evidence. No physical evidence linking Clay to the murder of Randy

Martindale was ever found. Hair fibers and fingerprints taken from the

crime scene did not match Clay or his clothes. The murder weapon was

never found. However, gunshot residue was actually found on the hands of

Stacy Martindale, and the State’s own expert witness testified that it

was possible she fired the handgun.

In addition, the State relied primarily on the testimony of two

people who not only admitted to plotting to kill Randy Martindale -- his

wife Stacy and her lover Chuck Sanders -- but also the two people who

had the most motive to do so.

Crucial to the prosecution’s case was their claim that Clay killed

Randy Martindale and escaped alone in Stacy’s car. However several

witnesses – including in an unsigned affidavit by the officer in pursuit

of the car – say they saw two people in the car.

When the officer arrived on the scene he reported both car doors

were open. Prosecutors allege Clay drove the vehicle alone, pulled over,

and had the wherewithal to climb over the center console and open both

doors in an effort to throw off police, then flee on foot.

The State claims another crucial piece of evidence linking Clay to

the crime was a live .380 caliber Remington shell (the same caliber used

to kill Martindale) found at 1 AM with a flashlight. According to State

Trooper Greg Kenley, the shell was lying on a wet strip of dew-covered

grass, and no footprints were evident in the area. Kenley marked the

shell and called Deputy Hopkins to take pictures of the apparent

evidence. The shell, which was dry but lying in wet grass, was found

“150-200 yards” away from the closest footprints the prosecution claim

were Clay’s when he exited out the passenger side of the car to flee.

That means Clay would have had to throw the bullet the length of nearly

two football fields after exiting the car, without leaving fingerprints.

The Guinness Book of World Records notes the longest recorded throw of a

baseball was 445 feet – or 148 yards.

In addition, State’s expert witness testified that casts taken of

the footprints were inconclusive as a match to Clay’s shoes. {See

testimony of Andy Wagoner Southeast Missouri Crime Lab}

Riley Bock's Theory of the murder plot and arrest of Clay

Prosecutor Riley Bock's theory is based on the belief that after

Stacy Martindale could not convince Sanders to kill her husband after

months of pleading, she was able to convince Clay to do it in 10

minutes.

Clay and Sanders then drove to the Martindale home, surprised Randy

Martindale and shot him three times and left in a Camaro blocked in by

Randy Martindale’s vehicle. Despite the fact that Clay would have had

access to both vehicles, but chose the one that was blocked by the other,

taking the time to make several point turns in an effort to get around

the other vehicle. According to Bock, Clay then drove calmly to the edge

of town passing several cars. Officer McFerren, was alerted to the car

and the sparks from the toy underneath the vehicle, not to someone

driving at a high rate of speed, recklessly, who supposedly just killed

someone in their home. Seconds later, Clay stopped the vehicle in a

panic, opened both car doors and turned on the windshield wipers, all to

confuse the police officer only seconds behind him, and then climbed

over a console and fled out the passenger's side door with the officer

in sight. While running through fields to escape police, Clay got scared,

paused, and threw one live .380 caliber shell “150 to 200 yards,” which

managed to land in wet grass but remaining completely dry, and without

any fingerprints.

This is a difficult theory to believe, at best. And if any primary

component of this conjecture is off, the case against Clay disintegrates.

Federal District Court Reverses Clay's Conviction

In May 2001, Federal district Judge Dean Whipple ordered a new trial

for Clay, citing that prosecutors Bock and special prosecutor Hulshoff

misrepresented a sentencing deal that they made with Sanders for his

truthful testimony at Clay's trial.

Later, Whipple ruled Bock and Hulshof were guilty of withholding

critical evidence that would have corroborated Clay’s testimony on the

night of Martindale’s murder —evidence, as Whipple believed, that would

have been beneficial to Clay’s claims of innocence.

Finally, Whipple added, Clay’s attorneys failed to conduct a

reasonable investigation through his inability to locate three witnesses

who saw the Camaro and its doors open simultaneously, and that Clay’s

defense was essentially ineffective assistance of counsel. {The 8th

Circuit Court of Appeals overruled District Judge Whipple and ordered

Clay's death sentence re-instated.}

1. The State Misrepresented Chuck's Plea Agreement

In the initial days following the crime, Chuck Sanders was charged

with first degree murder punishable by death in the murder of Randy

Martindale. However, Sanders was soon offered a deal by Bock for his

truthful testimony against both Clay and Martindale. For his testimony,

Sanders was offered a deal for five years probation, which by law was to

be made known to all defendants and their attorneys.

The State says it revoked that plea offer after Sanders reported

that he had disposed of a box of shells which he claimed to have

forgotten about when questioned on an earlier occasion. Having revoked

the original plea agreement, the State claimed that Sanders new plea

agreement called for ten years in prison for conspiracy to commit murder

in exchange for Sanders’ testimony, and as cited in the preliminary

hearing for Stacy Martindale.

While Chuck's attorney later filed a motion to enforce the original

plea agreement for probation, Sanders, while under questioning by

Hulshof, originally told the jury that he would be getting ten years in

prison for an unspecified crime. The actual testimony is as follows:

Q: (Mr. Hulshoff) Chuck, you've told us what you're charged with.

What do you understand the arrangement or agreement is between yourself

and the State of Missouri in exchange for your assistance or cooperation

in bringing the people to justice in this case?

A: (Mr. Sanders) My understanding of the current agreement is if I

tell what I know truthfully that it would be recommended that I receive

ten years in the State Penitentiary for an unspecified crime.

Q: (Mr. Hulshoff) Not probation but ten years?

A: (Mr. Sanders) Ten years in prison, yes.

Q: (Mr. Hulshoff) You understand that?

A: (Mr. Sanders) Yes sir.

On cross examination, Clay's attorney attempted to pursue the issue

of whether Chuck's real agreement with the State was for probation.

Chuck stated only that he believed he should receive probation and that

his attorney had filed a motion to enforce the original plea agreement.

On redirect, the State affirmed that Chuck's plea agreement was not for

probation, but for the ten years in prison.

Q: (Mr. Hulshoff) And at that point [Chuck admitted that he had

disposed of a partial box of .380 caliber shells and didn't tell them

before he was given the plea agreement] this plea agreement for

probation was revoked, was it not?

A: (Mr. Sanders) Yes, it was.

Q: (Mr. Hulshoff) What is your understanding of the sentence that

you are going to receive, that's going to be recommended by Mr. Bock

when you come to court?

A: (Mr. Sanders) My understanding is ten years in the penitentiary.

Q: (Mr. Hulshoff) And what do you hope for with your lawyer's help?

A: (Mr. Sanders) I hope that my lawyers will be able to, we have a

motion right now that's pending, I hope that my lawyers will be able to

argue the motion and make the prosecution stick to the original

agreement.

Q: (Mr. Hulshoff) But if that's unsuccessful, if some judge later on,

what is your expectation as to what sentence if any you will receive?

A: (Mr. Sanders) My lawyers have told me to count on the ten years

and if I get anything better, to be happy with it.

(Closing Argument by Prosecutor Kenny Hulshoff)

And in regard to Chuck Sanders, ladies and gentleman, Chuck Sanders

is going to get 10 years in prison ... Let there be no mistake about it.

Although no intervening event explains the State's position, the

State amended the information provided to the court and charged Chuck

Sanders with a Class D felony of tampering with evidence [Disposing of

the.380 Caliber partial box of shells] and ultimately recommended only

five years in prison. Hulshof and Bock had no intention of seeking the

ten years in prison against Chuck Sanders, and instead lied to Clay’s

jury.

Furthermore, the State agreed that Sanders’ could request a

presentencing report and argued that the five years in prison should be

suspended, that he should receive only probation. As a result of the

State's amendments to the sentencing court, Sanders’ attorneys withdrew

his motion to enforce the original agreement for probation at the time

of his plea.

On August 22, 1996, the State Court sentenced Sanders to five years

in the Department of Corrections, then suspended that sentence and

placed him on five years probation -- with no prison time. In an

affidavit to Clay’s attorney from Chuck Sanders dated April 14, 2001, he

rejects his trial testimony of the plea agreement as being true. The

following is the actual affidavit:

Chuck Sander's Affidavit April 14, 2001

That on the day of Clay's trial was scheduled to begin, I was in a

room at the courthouse with my lawyers (Dan Graylik & Nancy McKerrow),

the prosecutors (Riley Bock & Kenny Hulshoff) and other law enforcement

officials. My lawyers were discussing my plea agreement with the

prosecutors.

It was this day that I agreed to the ten year sentence in exchange

for my testimony. Riley Bock told me the ten years would be what was on

paper, but that he would not push it with my sentencing judge. Meaning

he would not try to push the judge to actually sentence me to the ten

years in prison.

Mr. Bock indicated that it couldn't appear to the jury that nothing

was going to happen to me or they would not believe my testimony. My

attorneys said that because the prosecutor wasn't going to push the ten

year sentence, the court would never give me such a sentence. I never

believed that I would receive a sentence of ten years in prison.

2. Trial Counsel's failure to conduct a reasonable investigation.

The American Bar Association Standards and the courts, including but

not limited to the U.S. Supreme Court, hold that a defense attorneys

duties include a full and complete investigation into any and all leads

that may show innocence, affect witness credibility, mitigate the

offense or punishment in any way, or show the caliber of police

investigation and or decision to charge the defendant.

The American Bar Association standard and the courts have stated

that this is required even in circumstances where the defendant has made

admissions of guilt. Clay’s trial attorneys never appeared to conduct

any type of investigation of his case -- there is not a single generated

report from his defense team at the time or any investigator on behalf

of Clay’s defense. Prior to his trial, no member of Clay’s defense team

or any investigator bothered to ask questions in New Madrid.

Clay’s attorneys only took depositions from the State's witnesses.

It was not until Clay’s post conviction relief did his new attorney,

Greg Mermelstein, discover through his personal investigation that there

were three statements made to police by three separate people who saw

Officer McFerren attempt to stop the Camaro the night of Randy's murder.

All three - Debra Garret, Scott Sullivan, and Samantha Fitzgerald --

ultimately gave personal affidavits claiming they saw two people in the

spark-emanating Camaro that night.

3. Prosecutorial Misconduct

Withholding Evidence Favorable To Defendant

For decades the United States Courts have constantly held that

prosecutors must disclose all evidence known to them, or known by the

police. Prosecutors are deemed not as representative of an ordinary

party to a controversy, but of sovereignty, and with an obligation to

govern impartially.

The individual prosecutor's duty is not to win the case, but see

that justice shall be done. {See Kyles V. Whitley 1995, Strickler v

Greene 1999, Banks v. Dretke 2004, Berger v. United States 1930}. These

three statements from Garret, Sullivan, and Fitzgerald were favorable

for Clay’s defense and corroborate his trial testimony, but were never

disclosed by Riley Bock.

Statement by Samantha Fitzgerald -- February 13, 2001

That on May 19, 1994 I was traveling in a car with my sister Deborah

Garrett, and my nephew, Scott Sullivan. We were returning home to New

Madrid from a friend's house. I first noticed a Camaro that we

recognized as Stacy's Martindale's car with sparks flying from under the

car. I then saw a police car that appeared to be trying to head off the

Camaro. I saw the Camaro stop and both doors open simultaneously. From

the way the police car was positioned, the officer could not see both

doors open at the same time due to all the dust that was being blown up

from the car.

That I also saw a two tone white Bronco sitting by the school close

to where the Camero stopped after the doors opened on the Camaro I

noticed that the Bronco was gone. That I live very close to the scene

where I witnessed the Camaro stop and after I returned home on the

evening of May 19, 1994 there were several police officers in the area.

I was interviewed by Officer Raymond Creasey of the New Madrid Police

Department about my knowledge of anything that happened that night. I

told Officer Creasey that I saw both doors open simultaneously. I was

never again contacted by the police or any attorneys prior to Richard

Clay's trial. If contacted by anyone I would have told him what I saw

and have been willing to testify to such information at any court

proceedings.

Scott Sullivan February 13, 2001

That on May 19, 1994 I was traveling in a car with my mother Deborah

Garrett and my aunt, Samantha Fitzgerald. We were returning home to New

Madrid from a friend's house. I first noticed a Camaro that we

recognized as Stacy's Martindale's car with sparks flying from under the

car. I then saw a police car that appeared to be trying to head off the

Camaro. I saw the Camaro stop and both doors open simultaneously. From

the way the police car was positioned, the officer could not see both

doors open at the same time due to all the dust that was being blown up

from the car.

That I also saw a two tone white Bronco sitting by the school close

to where the Camaro stopped after the doors opened on the Camaro I

noticed that the Bronco was gone. That I live very close to the scene

where I witnessed the Camaro stop and after I returned home on the

evening of May 19, 1994 there were several police officers in the area.

I was interviewed by Officer Raymond Creasey of the New Madrid Police

Department about my knowledge of anything that happened that night. I

told Officer Creasey that I saw both doors open simultaneously. I was

never again contacted by the police or any attorneys prior to Richard

Clay's trial. If contacted by anyone I would have told him what I saw

and have been willing to testify to such information at any court

proceedings.

Deborah Garrett February 13, 2001

That on May 19, 1994 I was traveling in a cat with my sister

Samantha Fitzgerald and my son Scott Sullivan. We were returning home to

New Madrid from a friend's house. I first noticed a Camaro that we

recognized as Stacy's Martindale's car with sparks flying from under the

car. I then saw a police car that appeared to be trying to head off the

Camaro. I saw the Camaro stop and both doors open simultaneously. From

the way the police car was positioned, the officer could not see both

doors open at the same time due to all the dust that was being blown up

from the car.

That I also saw a two tone white Bronco sitting by the school close

to where the Camaro stopped after the doors opened on the Camaro I

noticed that the Bronco was gone.

That I live very close to the scene where I witnessed the Camaro

stop and after I returned home on the evening of May 19, 1994 there were

several police officers in the area. I was interviewed by Officer

Raymond Creasey of the New Madrid Police Department about my knowledge

of anything that happened that night. I told Officer Creasey that I saw

both doors open simultaneously. I was never again contacted by the

police or any attorneys prior to Richard Clay's trial. If contacted by

anyone I would have told him what I saw and have been willing to testify

to such information at any court proceedings.

Other Troubling Facts

Rayburn Evans Affidavit February 91 2001

Rayburn Evans says that he is the best friend of Randy Martindale

and attended the trial of Clay and Stacy Martindale While at the

courthouse in Perryville, Missouri for the trial of Stacy Martindale in

October 1995, Evans talked to Officer Claude McFerrin about his

knowledge of the homicide.

“Officer McFerren told me that he saw two people in the Camaro that

he attempted to stop on the night of Randy Martindale was killed. In

addition, Officer McFerren told me that no matter what they tried to

make him say, he knew there were two people in the Camaro.”

Claude McFerren’s Unsigned Affidavit

That in May 19 1994 I was employed as a deputy for the New Madrid

County Sheriff's Department. That I was on duty May 19, 1994 when I

began to follow the red Camaro later identified as Stacy Martindale's

car. After the Camaro stopped I was the first person to approach the car

to determine whether it was empty. That while I was at the scene of the

red Camaro, one of the other officers who arrived was trooper Greg

Kenley of the Missouri Highway Patrol. Trooper Kenley asked me about a

set of footprints coming from the driver's side of the Camaro. I told

him that they must have been my prints as I had approached the driver's

side of the car and turned off the ignition. Any footprints that I left

on the driver's side of the car would have covered prints made by the

driver of the car as he exited the car.

That if I had been asked about any of the above information when I

testified at the trial of the State of Missouri v. Richard Clay I would

have testified to these facts during my trial testimony.

Len Deschler's (Private Investigator) Affidavit

That on February 9, 2001 traveled to New Madrid Missouri in an

attempt to obtain an affidavit from Claude McFerren, New Madrid City

police Chief, as to his knowledge of the Randy Martindale homicide. Mr.

Clay's attorney Jennifer Brewer and I met chief McFerren at the New

Madrid City Police Department at approximately 2:30 p.m. That Ms. Brewer

handed Chief McFerren the affidavit, which is titled affidavit of Claude

McFerren and is attached to my affidavit and asked him to review the

affidavit for errors. Chief McFerren then appeared to read the affidavit

and commented that paragraph two stating that he worked for New Madrid

County Sheriff's department at the time of the homicide was incorrect.

Chief McFerren stated that it should read New Madrid City Police

Department. Chief McFerren made no other corrections or changes to the

affidavit.

That chief McFerren then stated. "I don't see why I can't sign this"

McFerren then expressed concern that he should contact the prosecutor,

Riley Bock, to obtain Bock' approval before signing the affidavit

because Chief McFerren did not want to hurt his working relationship

with the prosecutor by doing anything against Bock's wishes.

That Chief McFerren then talked to Riley Bock on the phone and

stated that Bock wanted him to bring the affidavit to his office. Chief

McFerren then asked Ms Brewer and me to follow him to Bock's office,

which we did. Chief McFerren entered Bock's office with the affidavit

while Ms Brewer and I waited in the car. Approximately five minutes

later, Chief McFerren reappeared and told me that Riley Bock had told

him not to sign the affidavit. Chief McFerren apologized handed me back

the affidavit and we parted company.

Keith Neal Handwritten Affidavit

On April 7, 1999, I spoke with Claude McFerren outside of his house.

Claude told me that the night of Randy Martindale's murder he stopped a

vehicle with two occupants on Dawson Roadfor C&I driving. He thought the

driver was drunk.

When he approached the vehicle both doors were open, the windshield

wipers were on and the motor was running. There were footprints leading

away from both sides of the vehicle. While scanning the area for the

occupants he heard a car door slam shut just behind him. He believes

this was Chuck Sanders leaving the scene.

The grass was very tall in the ditches, so it would have been easy

for someone to hide there. He reached in and turned off the windshield

wipers and the ignition. At this time he had not heard about the

Martindale murder. He said he told the proper authorities all of this,

and believes that this information was not brought up in the trials.

He also said the idea of someone crawling across the console was

highly unlikely. It is also his opinion that Stacy Martindale is the one

who shot Randy Martindale.

Don Fields Deposition October 30, 1996

Don Fields was called by the prosecutor Riley Bock to testify at

Stacy Martindale's trial in October 1995. Clay’s trial attorneys never

knew of Mr. Fields as a potential witness. The following is the

deposition taken by attorney Greg Mermelstein who represented Clay at

his post conviction relief hearing.

Q: (Mr. Mermelstein) Did you see anything unusual at that time?

A: (Don Fields) Yes I seen a car coming towards us and sparks was

coming up from it.

Q: (Mr. Mermelstein) When you saw the car did you see what kind of

car it was at that time?

A: (Don Fields) Red Camaro.

Q: (Mr. Mermelstein) Did you note how may occupants were in the car?

A: (Don Fields) Looked like there was two in there to me.

Q: (Mr. Mermelstein) Now after you saw this did you report this

information to New Madrid Law Enforcement Officials?

A: (Don Fields) The next day or two I did.

Q: (Mr. Mermelstein) Now did you testify to this at the Stacy

Martindale trial? I think it was in Perryville Missouri. Do you remember

going there?

A: (Don Fields) Yes sir.

Q: (Mr. Mermelstein) Did you essentially testify at the trial if you

recall to the same information you did here today?

A: (Don Fields) Yes sir.

Q: (Mr. Mermelstein) Now Richard Clay had a trial in the summer of

1995 in Fulton, Missouri. It was late June early July. Did you receive a

subpoena for that trial to appear?

A: (Don Fields) No sir.

Q: (Mr. Mermelstein) If you had received a subpoena to appear there

would you have followed that subpoena and appeared in Fulton to testify?

A: (Don Fields) Yes sir.

Q: (Mr. Mermelstein) And would you have testified to the information

you did here today?

A: (Don Fields) Yes sir.

Why would Riley Bock call Don Fields to testify that he saw two

people in Stacy Martindale's red Camaro on the night Randy is murdered,

but not call this same witness to testify at Clay’s trial, or even to

disclose to Clay's attorneys Don Fields as a witness? At Clay’s trial,

Riley Bock vehemently contested the idea that there were two people in

the car.

Contradicting Theories of Who Shot Randy Martindale

At Clay’s trial in June 1995, the prosecution argued to the jury

that Clay shot and killed Randy Martindale. At Stacy Martindale’s trial,

the same prosecution argued that they didn't know who shot Randy

Martindale but that Stacy Martindale could be the shooter.

If Stacy Martindale is the shooter, Rick Clay must be innocent and

Riley Bock and Kenny Hulshoff have once again put an innocent man on

Missouri's death row. Clay raised this claim as a denial of his Due

Process of Law, but the appeals court denied him relief, claiming Clay

and his attorneys did not raise the issue during his motion for a new

trial following his conviction filed in July 1995.

However, this argument made at Stacy Martindale's trial in October

1995. How were Clay and his attorneys expected to know that in fact the

State would change their theory four months later as to who shot Randy

Martindale?

It would seem the court erred in not responding to Clay's claim and

by procedurally barring him from ever raising this claim again.

(Page 638 of Stacy's trial transcript Kenny Hulshoff explains their

new theory to the court.)

A: (Kenny Hulshoff) The officers did everything that they could to

adequately investigate this case and we are still yet unclear, the State,

since we don't have an eyewitness, don't know who pulled the trigger in

that bedroom, there was a glove present. The jury may talk and speculate,

the jury may find that the shooter, whether it was this defendant [Stacy

Martindale] or whether it was Richard Clay that the shooter wore a glove,

so I mean the point is you know a gunshot residue test was taken the

chemist can testify about elevated levels that would indicate that this

defendant [Stacy Martindale] could have handled a gun recently

(Page 639 of Stacy Martindale's trial transcript as her attorney

responds to Mr. Hulshoff.)

A: (Mr. Green) Then for the record I want to point out that Mr.

Hulshoff said that she may be the shooter. I find that for the first

time surprisingly that the State has is going to take the position that

Stacy Martindale is the shooter when they already tried Richard Clay and

their position then was that Richard Clay was the shooter of Mr.

Martindale.

Mike Frederick's Affidavit

That I testified for the State at the trial of State of Missouri v.

Richard Clay. That prior to my testimony I was in a room with the

prosecutor [Riley Bock] and he was insisting that I remember the exact

times of my contact with Mr. Clay on the night of May 19, 1994. I was

not aware of the precise times of my activities on that night and have

always been able to do no more than give my best estimates. While I was

in the room with the prosecutor prior to my testimony, the prosecutor

told me what questions I would be asked and what answers I should give.

When I testified the prosecutor led me through the times of the events

that happened the night of May 19, 1994.

Kenny Hayden Affidavit October 10, 1996

When Rick Clay and I went out to the Parking lot of J.D.'s on the

night of May 19, 1994 we both used some methamphetamine in the parking

lot. I provided the methamphetamine to use in the parking lot.

On the night of May 19, 1994 while at J.D.'s Clay told me that he

had to leave and run down the street to pick something up. When he told

me this he was referring to having to go pick up some drugs. I reported

this to officer Hinesly when he interviewed me on May 21, 1994 Rick had

told me that he was going to pick up some crank.

Chuck Sander's July 18th, 1994 interview

After Sanders was initially charged and arrested for Randy

Martindale's murder in early July 1994, he was taken to be held in the

Mississippi County Jail in Charleston, Missouri. While held there, he

was interviewed by Sgt. Hinesly of the Missouri State Highway Patrol on

July 11, 1994. The following Monday on July 18, 1994, in the office of

Chuck's first lawyer, James Robinson of Sikeston Missouri, Chuck was

offered a plea agreement to testify at the trial of Rick Clay and Stacy

Martindale.

In the 104 page July 18 interview, Sgt Hinesly refers to another

Monday July 11th interview on page 6. In fact, Sgt Hinesly and Riley

Bock both refer to the mysterious July 11th interview a total of

thirteen times. Bock and Sgt Hinesly both tell Chuck "You're lying to us,

you lied Monday and you're lying today."

To this day Riley Bock denies that the Monday July 11th 1994

interview exists. Regardless, Clay’s attorney had the legal right to

know what Bock and Hinesly claim Sanders was lying about in order to

cross examine Sanders and his truthfulness during Clay’s trial. What was

Chuck lying about and why does Riley Bock not want Clay and his attorney

to know?

Chuck Sander's July 28, 1994 Interview

On July 28, 1994, Corporal A.V. Riehl, Sgt. Hinesly, and Corporal

Riehl re-interviewed Sanders at the Mississippi County Jail in

Charleston Missouri. The following are details of Investigation Report

typed up by Corporal Riehl consisting of seven paragraphs. Details in

short are as follows:

Paragraph 2 -- states that they are giving Chuck a chance to recall

any facts.

Paragraph 3 -- states that they review the facts with Chuck and

inform him of a jail house informant who has written a statement against

Sanders and Clay and that the statement was on file at the New Madrid

County Jail.

Paragraph 4 -- Chuck reveals that he talked with Stacy on the

evening of May 19, 1994 on Radio Shack parking lot and she told him "that

this would be a good opportunity to do it". Chuck says he told her that

"he didn't want anything to do with her".

Paragraph 5 -- when asked to explain what the good opportunity was

interpreted as, Chuck said he understood it as "get rid of Randy" but

she never mentioned killing Randy, but he knew that's what she was

referring to because of previous conversations.

Paragraph 6 -- Chuck said that some months ago Stacy asked him to

help her get rid of Randy, Chuck said his reply was "I’ll think about it".

Chuck went on to say that he never intended to help her in any way but

thought that she would just forget about the whole idea after awhile.

Paragraph 7 -- Chuck did not provide any other information that was

new to the investigation of Randy's murder. He did say that he intended

to take the stand and testify to what he has told the police. When asked

to provide a written statement he elected to seek the advice of counsel

before giving a written statement.

Letter from Riley Bock's Office to Chuck Sander's lawyer

Letter to Nancy McKerrow Lead Trial Counsel for Chuck Sanders August

30, 1994

OFFICE OF THE PROSECUTING ATTORNEY

NEW MADRID COUNTY, MISSOURI

August 30, 1994

Ms. Nancy McKerrow

Lead Trial Counsel

Central Capital Litigation Division

Office of State Public Defender

3402 Buttonwood

Columbia, Missouri 65201-3723

Re: State of Missouri vs. Charles Sanders

Case No. CR294-420F

Dear Nancy:

I enclose here with the copy of the officer's report related to the

recovery of the shells following our interview with your client. The

information given by your client the morning after our long interview

directly conflicts many of his statements and claims that afternoon. I

am also enclosing copies of the interview had with Darrell Jones.

The time for your client to come clean and be of use to the State,

and himself, is quickly coming to an end. I have always operated under

the philosophy that a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush. Your

client is in hand. It is obvious at this point in time that he was

involved in the conspiracy to kill Randy Martindale. His previous claims

of withdrawal are not supported by the evidence nor by the many

inconsistencies he has provided. We would be willing to make one last

effort at obtaining the truth from him.

Very truly yours,

H. Riley Bock

Prosecuting Attorney

HRB/mmt

cc: Mr. Robert J. Ashen

###

Neither Clay nor his attorneys ever knew of this letter to Chuck's

attorney from Riley Bock – It in itself raises a few questions.

Through Bock’s own words, we can clearly see he did not believe

Sanders and "his many inconsistencies.” Therefore, what makes Sanders

suddenly so credible to serve as the linchpin in the State’s case

against Clay a few months later?

Again – what are these “inconsistencies” and what lies in the mind

of Bock are Sanders giving as to warrant “one last effort at obtaining

the truth?” Sanders never conducted any more substantive interviews

after this letter.

Conviction: A Double Entendre with Only One True Meaning

From almost the beginning, Stacy Martindale tried to blame Sanders

and Clay for the murder of her husband. In an interview on June 6, 1994,

Sgt Steve Hinesly told Martindale that there were only two people who

knew the truth about Randy's death. Martindale replied "yeah Chuck and

Rick." Sgt. Hinesly told her "no, you and God.”

On February 20, 1994 Randy Martindale stopped Stacy Martindale on

Interstate 55 outside of Benton, Missouri and -- according to the

Highway Patrol report -- accosted her in front of their kids. Chuck

Sanders even told Stacy, "that if she was a battered spouse, she needed

to get herself a gun and when he beat her she could kill him and then

she could claim spousal abuse.”

According to sources from New Madrid, Stacy's father and Randy

Martindale even had an altercation over Randy's abuse of Stacy at the

local Eagle's club.

Each of these things - the documented Interstate 55 incident,

Chuck's advice on how to kill Martindale, her affair with Sanders, and a

tempting $100,000 life insurance policy -- is evidence enough of a

history of abuse and motive for Stacy to kill her husband.

Excerpts from the deposition of Sanders on April 24, 1994 by Clay’s

defense team documents Sanders instability and volatile emotional state

stemming from his obsession with Stacy Martindale. Excerpts such as:

"I was kind of upset that she left without saying goodbye. There

didn't seem to be any kind of closure or resolution to the conflict and

Rick said that he tried to make plain to her my position and he said

that maybe he hadn't understood what my position was with her, you know,

if I wanted to carry on the relationship or what.

“I got a little bit miffed with Rick, you know, because I wanted him

to make everything good and right."

“When Clay’s lawyer asked Chuck was it his intention that Clay tell

her you still had feelings for her, but you did not want to get involved

in anything illegal or what was your intention for him (Rick) to tell

her?”

Chuck responded "No, I meant for him to get the relationship part

straight. I had made myself plain to her as far as being involved with

the killing of Randy goes. I wanted him (Rick) to explain to her that I

still cared for her and wanted to see my son, but I didn't want to be

badgered anymore or I didn't want her to bring this to me anymore."

Clay's brief conversation with Stacy Martindale the basis for Riley

Bock's murder for hire scheme. Sanders, by his own admission, simply

asks his friend to play Dear Abby for the sake of Chuck and Stacy's

torrid love affair. There is no evidence that Clay ever or in anyway

agreed to kill Randy Martindale. Sanders even told the court that Clay

told him “that would be a crazy thing to do."

What the prosecution seemed content to ignore was the simple fact

that both Sanders and Stacy Martindale planned and plotted to kill Randy

Martindale for months. A witness added Stacy Martindale and Sanders

practiced shooting Sanders’ .380 caliber handgun on the levee outside of

New Madrid.

Stacy Martindale’s own sister says that Sanders came to Stacy's

house and gave her something in a bag shortly before Randy's murder.

The lack of evidence and witnesses implicating Clay is mind-boggling.

In the years after the crime, people came forward and offered their

testimony – people like Randy Martindale’s own friend Rayburn Evans or

Keith Neal, Don Fields, and the three witnesses who saw the Camaro that

night. They are people that owed nothing to Clay, but who were

downplayed and dismissed by prosecutors with their own agenda – lawyers

who worried that new witness testimony may taint their best chance at

maintaining their claim to high profile conviction. These were the

people that might reveal Hulshof and Bock were wrong, and ruin a run at

the Governor’s mansion.

In 2001, a journalism class from Webster University in St. Louis

took up Clay’s fight after reading his case, shocked at the

inconsistencies and the fact a court can condemn a man to die based on

so little evidence. The class told Clay they couldn’t believe that

Sanders – who admitted to conspiring to killing Randy Martindale and who

was originally charged with first degree murder – was given just five

years probation for tampering with evidence.

It was inconceivable to these students that the two people who

literally and admittedly planned to kill Randy Martindale had either

never spent a single day in prison, or who are now freed from jail and

carrying on their lives.

Some of the students asked how you can convict a guy to die despite

the fact that nothing – even fingerprints and hair submitted from the

crime scene – linked Richard Clay to murder.

They never saw an analysis of Chuck Sanders’ hair or Chris Black's

fingerprints. Black, Stacy Martindale’s lover from Michigan who sent

several letters to Stacy a month before her husband was murdered, was

never even considered as a suspect.

Coupled with the diligence and hard work of Clay's attorneys -

Jennifer Herndon and Elizabeth Carlyle -- the class’s curiosity and

prodding won Clay a new case in 2002. But his appeals were later

dismissed, due in large part to mistakes attributable to his original

court appointed defense team.

Unfortunately for Clay, his prior police record and reputation as a

drug dealer made him the most convenient suspect in the murder of Randy

Martindale, and the easiest to convict. The simple fact he was there

that night condemned him, in the wrong place at the wrong time, along

with the split second decision to run based on a belief another drug

arrest would disappoint his family. The fact he served his country as

U.S. Marine didn’t make him a hero, it made him the most proficient in

the use of a handgun of the three people near the Martindale house that

night.

Rick Clay will be the first to tell you that he’s made mistakes. He

sold methamphetamine to supplement income, he drank, and took drugs. His

marriage had failed and ended in divorce, and the relationships with his

family had been strained by a freewheeling lifestyle and the company he

kept. He’d been given second chances and wasted them, but like any 29

year old from a small town with a ton of friends, he always figured

there’d be a third.

But almost every person who knew him then and knows him today will

tell you Rick would do almost anything for those he would sometimes

disappoint the most. He’s a brother who still calls his little sisters

at least once a week. He’s a son who continues to talk to his mother

about God, a son who joined the Marine Corps after high school to honor

the legacy of his dad who died in Vietnam. He’s a father himself, who

simply wants the best for his own son. And to this day, he’s a good

friend to most of those same people he ran with 15 years ago, many of

whom still make a six hour drive to see him on weekends for food day.

He’s the former Kelly High School prom king; he’s that guy that would be

willing to help you sort things out with your girlfriend, despite the

fact he thought she was a ticking timebomb.

Just ask Chuck Sanders.

But he’s also the guy that wouldn’t reveal the friends who saw him

that night with Sanders and Stacy Martindale before leaving Sikeston,

all because he knew the drug-related questions the police would ask

might bring problems for them as well. Some of those people have chosen

to remain quiet to this day, but Rick astutely realizes that their

reluctance to talk is now between them and God.

Yet each and every person who knows him understands Rick Clay is not

a killer. He would never make the decision to kill the husband of a

woman he didn’t trust, not after a ten minute conversation in a car on

the way to Hardee’s.

That night in New Madrid, as he hid in the woods behind a levee,

Clay says he made a promise to himself. That if he somehow made it

through this mess, if the police realized they were fruitlessly looking

for a small-time drug peddler in flooded plain, and he was able by the

grace of God to get home – he’d change. He’d change the sake of his god-fearing

parents, two brothers and three sisters. He’d change for the sake of his

ex-wife who he now considered a friend. Most importantly, he’d change

for the sake of his then six year old son, Kiefer.

Today, Rick Clay still sits on Missouri’s death row and says he

expects to be executed for the murder of Randy Martindale. He adds he

has little time to worry because, as he says, “hate and anger is like