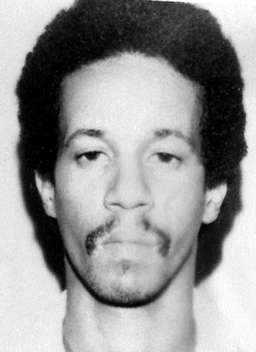

Leo Edwards Jr., a black man whose conviction by an all-white jury brought cries of racism by his attorneys, was put to death in Mississippi's gas chamber early today.

Mr. Edwards, 36 years old, convicted of murdering a convenience store clerk in a 1980 crime spree, lost two appeals just hours before the execution. He was pronounced dead at 12:15 A.M. at the Mississippi State Penitentiary here.

On Tuesday, the United States Supreme Court voted 7 to 2 to deny his request for a stay of execution. The Court's ruling was followed two hours later by a statement from Gov. Ray Mabus saying he refused to grant clemency to Mr. Edwards.

''I have reviewed the facts in the case of Leo Edwards, and I will not stand in the way of the court's justice,'' the Governor said.

''The facts are that Leo Edwards is a mass murderer who killed in cold blood, he tried and failed to get relief in 16 appeals to the courts, and discrimination had no bearing on his case.

''This is not casual justice. Leo Edwards' sentence is a result of his own crime, and his fate now rests in God's hands,'' the Governor said.

Mr. Edwards, of New Orleans, was convicted on April 1, 1981, of the death of a Jackson convenience store clerk, Linzy Don Dixon, during a robbery. The robbery and killing were committed after Mr. Edwards escaped from a Louisiana prison.

He and a co-defendant, Mike White, went on a five-day robbery spree that left three store clerks dead and two wounded in Hinds and Madison Counties.

Mr. White pleaded guilty to murder in Mr. Dixon's death and the slaying of a bar owner, Lee Ardis Newsome. Mr. White was sentenced to two life terms.

Mr. Edwards was sentenced to life in Mr. Newsome's killing.