No. 73,804

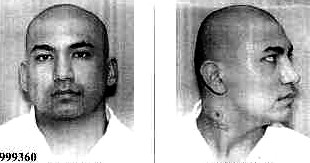

Juan Martin Garcia, Appellant

v.

The State of Texas

On Direct Appeal from Harrys

County

Holcomb, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which Keller,

P.J., and Meyers, Womack, Johnson, Keasler, Hervey, and Cochran,

JJ., joined. Price, J., joined the judgment, but not the opinion,

of the Court.

OPINION

A Harris County jury found appellant, Juan

Martin Garcia, guilty of capital murder. See Tex. Pen. Code §

19.03(a)(2) (murder in the course of robbery). The trial court,

acting in accordance with the jury's answers to the punishment

stage special issues, sentenced appellant to death. Appellant now

brings three points of error to this Court. We will affirm.

The evidence presented at appellant's trial

showed that during August and September of 1998, he and three

accomplices went on a crime spree in Harris County. As part of

that crime spree, appellant attempted to rob 32-year-old Hugo

Solano. When Solano refused to hand over any money, appellant shot

him four times in the head and neck, killing him. It was for that

murder that appellant was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death.

In his first point of error, appellant argues

that his trial counsel rendered ineffective assistance, in

violation of the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution,

(1) when, during

the punishment stage of trial, counsel elicited certain damaging

testimony from defense witness Dr. Walter Quijano, a clinical

psychologist. Appellant, an Hispanic, argues that the testimony in

question "tacitly asked [the jury] to consider race and ethnic

stereotypes" in its determination of the first punishment issue,

which concerned his future dangerousness to society.

(2)

The record reflects that defense counsel's

examination of Quijano covered his educational and professional

background first and then turned generally to the subjects of

predicting and, within a prison setting, controlling an

individual's proclivity for criminal violence, i.e., his

dangerousness. Defense counsel's examination also touched briefly

on the subject of race vis-a-vis an individual's dangerousness:

Q [by Defense Counsel]: Dr. Quijano, are there

certain factors that contribute to someone's dangerousness in

society?

A: Yes.

Q: And can you tell us what those are?

A: Although dangerousness is difficult to

predict, we know that there are certain factors that are

associated with increased dangerousness or the absence of the

factors with decreased dangerousness....

* * *

Q: Can you tell us what those factors are?

A: There are three groups of factors. The first

group is called statistical. The second group, called

environmental. And the third group, I call clinical.

Q: And can you tell us what is in the first

group or cluster of factors, if you will?

A: The first group, called statistical factors,

include the age of the person, which is the best predictor of

dangerousness. The younger the person, the more dangerous. The

older the person, the less dangerous.

Prior assaultive crimes or prior assaults is

also a strong predictor. The more prior assaults, the more

violence in the past, the more dangerous in the future.

The use of drugs and alcohol during the

commission of these assaultive events increases the probability of

violence, and then, finally, the use of a weapon, the presence of

which increases dangerousness. The absence of which decreases

dangerousness.

Q: Does sex play a role?

A: Sex in the sense of gender plays a role in

that males are statistically more violent than females.

Q: What about whether or not someone is

black, white, Hispanic? Does that play a role?

A: The race plays a role in that the -

among dangerous people, minority people are overrepresented in

this population. And, so, blacks and Hispanics are overrepresented

in the - in the dangerous - so-called dangerous population.

Q: What about economics?

A: Economics and stability of work record are

also important in that the more unstable the work history or the

more unstable the socioeconomic standing, the poorer the people,

the more likely they are to be dangerous than those with steady

employment and a reasonable socioeconomic status.

Q: What about whether or not there's any

substance abuse?

A: Substance abuse, again, is a high risk

factor in the future of violence.

Q: Now, are these - are some of these factors

eliminated in a prison environment?

A: Most of these factors are either eliminated

or kept to a minimum, reduced to a minimum within the prison

setting. Those factors that are biographical [biological?]

are, of course, not eliminated, your gender and your race.

Q: How are these certain factors eliminated in

a prison setting?

A: Many of these factors are controlled,

eliminated, kept to a minimum in the prison setting because of the

controls that the prison system inflicts on the inmates. For

example, weapons: although there are weapons in the prison, there

is intense supervision so that they're kept to a small minimum.

The presence of alcohol and drugs: there is alcohol and drugs in

the prison, but, again, it's difficult to get them. So, those are

two examples where the factors that contribute to dangerousness

are kept to a minimum in the prison system.

* * *

Q: Can dangerousness be situational?

A: Dangerousness is an interaction between what

the person is and where he is or under what environmental controls

the person is under. So that dangerousness would increase if the

person is under a loose supervision setting, such as in the free

community, and it would decrease dramatically in the prison where

there is much controls imposed on him.

* * *

Q: Are there certain safeguards at TDC [Texas

Department of Corrections] that decrease one's dangerousness?

A: The -

Q: Such - I apologize, Doctor. Go ahead.

A: The answer is "yes." The whole stance of the

prison system is to house these inmates, many of whom are violent

and dangerous in the free community, to house them in a safe

manner. So, there are many procedures and techniques that are

intended to suppress whatever dangerousness that inmates bring

with them.

* * *

Q: Is the amount of dangerousness in someone,

is it activated by certain environmental factors?

A: Yes.

Q: How does that fit in with being in a prison

setting?

A: A person who has many characteristics or

factors associated with dangerousness can go to the prison and

much of those factors are either no longer relevant, such as

employment, financial stability, and the prison system takes over

those factors and subdues whatever dangerousness a person comes

in. And, so, a person's dangerousness - the same person, the same

person's dangerousness may be higher in the free world and lower

in the prison, higher in some sections of the prison and lower in

some sections of the prison.

* * *

Q: Can someone in prison continue with

threatening or assaultive behavior?

A: Threatening may continue. Assaultive, there

is a point at which that is subdued.

Q: And why is that?

A: Because the prison system will do what it

can to subdue assaultive, violent behavior in the prison. Now,

threats, verbal threats, they may not be able to do much about

that because they cannot shut the mouth, but actual overt assaults

can be controlled physically, and TDC will apply whatever measures

are necessary to control that.

The record does not reflect defense counsel's

reasons for examining Quijano on the subject of race vis-a-vis an

individual's dangerousness.

The Sixth Amendment guarantees the right to the

reasonably effective assistance of counsel in state criminal

prosecutions. McMann v. Richardson, 397 U.S. 759, 771 n.

14 (1970). In general, to obtain a reversal of a conviction on the

ground of ineffective assistance, an appellant must demonstrate

that (1) defense counsel's performance fell below an objective

standard of reasonableness and (2) there is a reasonable

probability that, but for counsel's unprofessional error(s), the

result of the proceeding would have been different.

(3)

Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 687 (1984). In

assessing a claim of ineffective assistance, an appellate court "must

indulge a strong presumption that counsel's conduct [fell] within

the wide range of reasonable professional assistance; that is, the

[appellant] must overcome the presumption that, under the

circumstances, the challenged action might be considered sound

trial strategy." Id. at 689 (some punctuation omitted).

Also, in the absence of evidence of counsel's reasons for the

challenged conduct, an appellate court "commonly will assume a

strategic motivation if any can possibly be imagined," 3 W. LaFave,

et al., Criminal Procedure § 11.10(c) (2d. ed 1999), and

will not conclude the challenged conduct constituted deficient

performance unless the conduct was so outrageous that no competent

attorney would have engaged in it. See Thompson v. State,

9 S.W.3d 808, 814 (Tex.Crim.App. 1999). Finally, an appellant's

failure to satisfy one prong of the Strickland test

negates a court's need to consider the other prong. Strickland

v. Washington, 466 U.S. at 697.

Appellant has failed to demonstrate that his

trial counsel's performance fell below an objective standard of

reasonableness. Counsel might have been attempting, with Quijano's

testimony, to do two things: (1) place before the jury all the

factors it might use against appellant, either properly or

improperly, in its assessment of his future dangerousness and (2)

persuade the jury that, despite all those negative factors,

appellant would not be a future danger if imprisoned for life

because the prison system's procedures and techniques would

control or eliminate his tendency toward violence. Under the

circumstances - the State had already presented evidence before

the jury that appellant had a long and violent criminal record -

we cannot say that counsel's conduct could not be considered sound

trial strategy. We overrule appellant's first point of error.

In his second point of error, appellant argues

that the evidence adduced at trial was legally insufficient to

support the jury's affirmative answer to the first punishment

issue. As we noted in footnote three, supra, the first

punishment issue asked the jury to determine "whether there is a

probability that the defendant would commit criminal acts of

violence that would constitute a continuing threat to society."

See Tex. Code Crim. Proc. art. 37.071, § 2(b)(1). The State had

the burden of proving the first punishment issue beyond a

reasonable doubt. Id. at § 2(c). Thus, the State had the

burden of proving beyond a reasonable doubt that there is a

probability that appellant, if allowed to live, would commit

criminal acts of violence in the future, so as to constitute a

continuing threat to people and property, whether in or out of

prison. Ladd v. State, 3 S.W.3d 547, 557 (Tex.Crim.App.

1999), cert. denied, 120 S.Ct. 1680 (2000). In

its determination of the issue, the jury was entitled to consider

all of the evidence presented at trial. See Tex. Code Crim. Proc.

art. 37.071, § 2(d)(1). As an appellate court reviewing the legal

sufficiency of the evidence to support the jury's affirmative

finding, we consider all of the record evidence in the light most

favorable to the prosecution and determine whether, based on that

evidence and reasonable inferences therefrom, a rational jury

could have found beyond a reasonable doubt that the correct answer

to the first punishment issue was "yes." Ladd v. State, 3

S.W.3d at 558. This standard of review gives full play to the

jury's responsibility fairly to resolve conflicts in the evidence,

to weigh the evidence, and to draw reasonable inferences from the

evidence. See Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307, 319

(1979). If, given all of the evidence, a rational jury would have

necessarily entertained a reasonable doubt as to the probability

of appellant's future dangerousness, we must reform the trial

court's judgment to reflect a sentence of imprisonment for life.

Tex. Code Crim. Proc. art. 44.251(a).

Viewed in the necessary light, the evidence at

trial established that (1) on June 24, 1992, when appellant was

twelve years old, he committed the offense of terroristic threat;

(2) on May 6, 1993, when appellant was thirteen years old, he

committed misdemeanor theft; (3) on August 31, 1998, when

appellant was eighteen years old, he committed three separate

aggravated robberies; (4) on September 15, 1998, appellant again

committed aggravated robbery; (5) on September 17, 1998, appellant

shot and killed Hugo Solano, the victim in this case; (6) on that

same date appellant also committed two aggravated robberies; (7)

on September 20, 1998, appellant committed aggravated robbery and

attempted capital murder; (8) on September 21, 1998, appellant

committed aggravated robbery and attempted capital murder; and,

finally, (9) on one day in November 1999, while appellant was

incarcerated in the Harris County Jail awaiting trial in this

case, he committed misdemeanor assault.

We conclude that the evidence adduced at

appellant's trial was legally sufficient to support the jury's

affirmative answer to the first punishment issue. Given the

evidence of appellant's extensive criminal history, a rational

jury could have concluded beyond a reasonable doubt that he

exhibited a dangerous aberration of character, that he was

essentially incorrigible, and that the correct answer to the first

punishment issue was "yes." We overrule appellant's second point

of error.

Finally, in his third point of error, appellant

argues that "[t]he trial court reversibly erred in not charging

the jury [at the punishment stage] that extraneous offenses [must]

be proved by the [prosecution] beyond a reasonable doubt." We have

rejected identical arguments before, however. "As long as the

punishment charge properly requires the State to prove the special

issues, other than the mitigation issue, beyond a reasonable doubt,

there is no unfairness in not having a burden of proof instruction

concerning extraneous offenses." Ladd v. State, 3 S.W.3d

at 574-575. We overrule appellant's third point of error.

Appellant has shown no reversible error.

Accordingly, we affirm the judgment of the trial court.

DELIVERED OCTOBER 3, 2001

PUBLISH

1. The Sixth Amendment

provides in relevant part that "[i]n all criminal prosecutions,

the accused shall enjoy the right ... to have the assistance of

counsel for his defence." This right to counsel was made

applicable to state felony prosecutions by the Due Process Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment. Gideon v. Wainwright, 372

U.S. 335, 345 (1963).

2. The first punishment

issue asked the jury to determine "whether there is a probability

that the defendant would commit criminal acts of violence that

would constitute a continuing threat to society." See Tex. Code

Crim. Proc. art. 37.071, § 2(b)(1).

3. In some circumstances,

none of which are applicable here, a showing that the result would

have been different is not sufficient to show prejudice. See

Williams v. Taylor, 120 S.Ct. 1495, 1512 (2000).