The convict, Billy Conn Gardner, said in a brief

final statement, "I forgive all of you, and I hope God forgives all

of you all."

His mother, Nettie Gardner, replied, "I've never

been more proud of you than I am now."

Mr. Gardner's relatives hugged and sobbed. His

sister, Betsy Gray, said afterward: "My brother was convicted of a

crime he did not commit. Tonight, once again, the State of Texas has

committed cold-blooded murder. They are mass-murdering people here

almost as bad as if we're in a war."

Texas has executed more people this year than any

other state, and its 91 executions since the death penalty was

reinstated in 1976 also leads the nation.

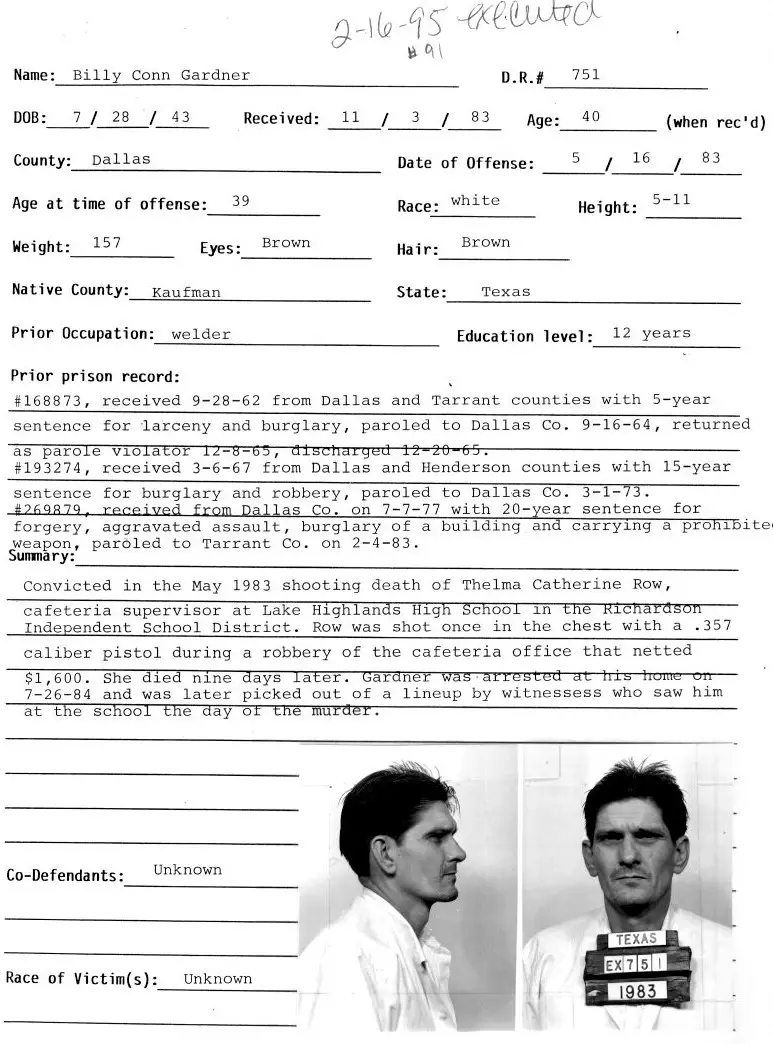

Mr. Gardner was convicted in 1983 of killing

Thelma Row, a cafeteria supervisor at Lake Highlands High School in

Dallas.

Mrs. Row, 64, was counting the day's receipts in

a back room when she was confronted by a robber and shot in the

chest with a .357-caliber pistol. The robber fled with about $1,600;

Mrs. Row died 11 days later.

The husband of another cafeteria worker

acknowledged being involved with the robbery, but said Mr. Gardner

was the gunman.

Mr. Gardner first went to prison at the age of 19

after he was convicted of larceny and burglary; at the time of his

execution, he had 10 other felony convictions.

When he was arrested in the killing of Mrs. Row,

he was on parole after having served fewer than six years of a 20-year

sentence for forgery, assault, burglary and carrying a prohibited

weapon.

That conviction came while he was on parole for

burglary and robbery.

Innocent or not, it's too late now for Billy

Conn Gardner

By William Janz - Milwaukee

Sentinel

February 24, 1995

She

received his last letter after he was dead.

For seven years, Christine M. Wiseman, an attorney

and associate professor at Marquette University Law School, fought to

put off Billy Conn Gardner's last day, but she, and he, ran out of

time last week.

It was just past midnight on Feb. 16. Gardner, 51,

was strapped down in the death chamber in a prison in Huntsville,

Texas, with a microphone near his face; he denied for the 1,000th time

that he had murdered a 64- year-old cafeteria worker 12 years ago,

then was executed by injection.

"Woe to you if you're poor," Wiseman said.

She compared justice for the poor, and justice for

the rich, such as alleged murderer O.J. Simpson, who is represented by

millions of dollars worth of attorneys.

"You can buy all the justice you want," she said. *

* *

"Dear Christine: . . . I hold out no hope at all.

Now, I want to thank you and David and E.J. for all you have done on

my behalf to try to save me, and it comes from my heart. I am fully

aware that isn't much, but it is all I have to offer any of you. . . .

"I sure don't want you to ever take on any guilt,

or feel that you have failed me, Christine. You know as well as I do

that my trial and appeal attorneys sold my life for the money the

court paid them to represent me. My fait (sic) was sealed before you,

E.J., and David ever became involved in my case.

"I love all of you for being so kind to my family,

and for treating them with respect. . . . Your husband and your family

should feel blessed. Over the years you showed me that you are a

person of your word, and I learned to trust you, and respect you, and

love you . . .

"I will depart this world with you in my thoughts,

and a special place in my heart for you. So please, never feel I hold

hard feelings for you, or blame you for anything, especially my death

. . .

"Goodby, Christine, and I thank God for letting me

know you. Love and respect, Billy." * * *

In 1988, Wiseman heard about Gardner, and

volunteered to represent him. For seven years of trips to court and

trips to Texas, she was paid nothing. She put a thumb and forefinger

together, made a zero, and held it up.

"Billy was worth it," she said.

A few days after she agreed to take the case,

Wiseman, who was a member of the board of the American Civil Liberties

Union of Wisconsin Foundation, received an emergency call. Gardner's

execution had just been set for the following month. When she applied

for an order to stop the execution, the state of Texas objected

because she wasn't certified to practice in the state.

She discovered that Texas had some peculiar

courtroom procedures, but even she found it difficult to believe that

Texas wanted to "execute someone because he isn't represented by Texas

counsel," she said.

"In Texas, killing is more important than making

sure they have the right person. Killing death row inmates is an

industry down there. Has it stopped crime? No, it's worse."

Even if you don't agree with her, you can

understand her bitterness. She maintains she was the attorney for an

innocent person.

"There are no moneyed people sitting on death row,"

she said.

Thelma Row, a cafeteria worker, didn't have much

money, either. She was shot to death in a robbery in a high school in

Dallas in 1983. Witnesses said the killer had reddish hair and a

goatee. Gardner had neither.

Named after a former light heavyweight boxing

champion, Gardner was a career criminal who was pushed into his

profession when he was 9 years old. At that age, he was given his

first hit of heroin by a relative. He became a drug runner, and spent

much of his life breaking the law, but he was never violent, Wiseman

said.

Another criminal, who was given substantial breaks

for his testimony, identified Gardner as the killer. During the

appeals process, Wiseman elicited testimony that Gardner's trial

lawyer had a 15-minute discussion with him before his trial, which

ended in a sentence of death.

The public is often critical of lawyers, and some

contend that they don't sneeze without charging someone for momentary

discomfort. However, once Wiseman was permitted to practice in Texas,

she not only represented Gardner free of charge, she even paid some

expenses herself. She received great help from David Bourne, a former

law student of hers who now is an attorney at Quarles & Brady. The

firm paid some expenses involved in the appeals. And E.J. Hunt,

another Wisconsin lawyer, also assisted the defense.

Last week, she and Bourne visited Gardner shortly

before he was executed.

"He cried, and we cried," Wiseman said.

Early in the day, he joked with her. Later in the

day, she joked with him. Jokes kept them from crying.

"I said that in seven years he had taken me on many

an interesting date, but this last one was extraordinary," Wiseman

said.

Gardner joked about heaven being empty of lawyers.

Just before his attorney left, Gardner mentioned

someone he never met. He wanted a 14-year- old to be a good boy, and

make his mother proud of him, he said. He referred to Wiseman's son:

"Say goodbye to Patrick for me," Gardner said.

In her office at Marquette, Wiseman began to cry.

With tears in her eyes, she told how she and Bourne

stood outside the prison, and stared at a prison wall, where there

were eerie, yellow lights. It was raining.

"The chaplain said it always rains when there's an

execution in Huntsville," Wiseman said. "I said, `Doesn't anyone get

the hint?'"

A wire service reported that just before he was

executed, Gardner said, "I forgive all of you and I hope God forgives

all of you."

Nettie, his mother, said, "I've never been more

proud of you than I am now."

Gardner's sister, Barbara Gray, stumbled out of the

building after watching her brother gasp, and jerk, and die.

"Don't let anyone tell you this is a peaceful way

to die," she said. "It's a lie, it's a lie, it's a lie."

Texas cops and courts insisted Gardner was guilty.

Wiseman and Gardner's family insisted that he was not guilty. But, for

Gardner, it no longer matters. He's dead.