Alvin Urial Goodwin, III,

Petitioner-Appellant,

v.

Gary L. Johnson, Director, Texas Department of

Criminal Justice,

Institutional Division, Respondent-Appellee.

No. 95-20134

Federal

Circuits, 5th Cir.

January 15, 1998

Appeal from the

United States District Court for the Southern

District of Texas.

Before KING, JOLLY and DeMOSS,

Circuit Judges.

KING, Circuit Judge:

The opinion entered in this cause

on December 23, 1997, is withdrawn, and the

following opinion is substituted therefor.

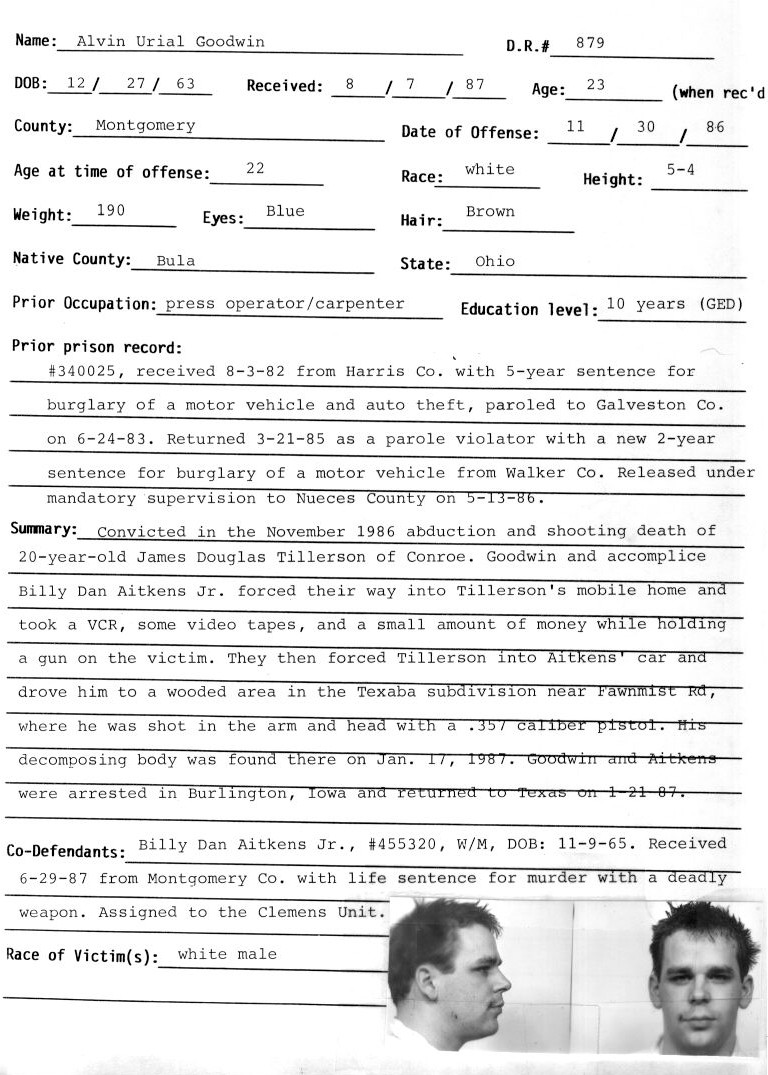

Alvin Urial Goodwin, a Texas

death row inmate convicted of capital murder,

challenges the district court's denial of his

petition for a writ of habeas corpus. Goodwin has

alleged, among other things, that his appellate

counsel provided constitutionally ineffective

assistance because he failed to raise a state law

issue that would have required reversal on direct

appeal. We affirm the district court's denial of

habeas relief on this claim because the trial

court's error that formed the basis of this omitted

issue on appeal did not render Goodwin's trial

fundamentally unfair or its result unreliable.

We also affirm the judgment of

the district court denying relief in all other

respects, except that we vacate that portion of the

district court's judgment denying Goodwin habeas

relief on his Fifth Amendment claim and remand for

an evidentiary hearing to resolve the fact issue

underlying that claim.

I. FACTUAL BACKGROUND

On December 1, 1986, Montgomery

County Sheriff's deputies received a report of a

theft at the trailer house of James Douglas

Tillerson. Further investigation revealed that

Tillerson's trailer house had been ransacked and

that a VCR, some video cassettes, phonograph records,

and a bayonet were missing from the house. Tillerson

had not reported for work that morning and had not

been seen since the previous Sunday.

On January 17, 1987, trail riders

discovered Tillerson's body approximately two and

one-half miles from his trailer at the edge of the

woods near Fawnmist Road in Montgomery County. An

examination of Tillerson's body disclosed that he

had been dead for approximately one month and had

died from a gun-shot wound to the head. A second gun-shot

wound had been made by a bullet entering Tillerson's

right arm and exiting at the forearm. A bullet was

recovered from the body's clothing and fragments of

a bullet were later discovered in the immediate area

where the body had been found.

Friends of Tillerson informed

police that Tina Atkins, also a friend of the victim,

had told them that a VCR, bayonet, and several video

tapes from Tillerson's trailer were now at the house

where she lived with her father, Billy Dan Atkins,

Sr. Tina Atkins was able to name the titles of the

video tapes, which corresponded with the titles of

the tapes missing from Tillerson's trailer. Based on

the information that she provided, a search warrant

was issued for the residence of Billy Dan Atkins,

Sr., who informed police that he had retrieved the

items from the car of his son, Billy Dan Atkins, Jr.

(Atkins).

Further investigation revealed

that Atkins, Goodwin, Glenn Dierr, and Fred Meadows

had been arrested for unlawful possession of a

firearm by a felon on December 4, 1986, in The

Woodlands, Texas. Following the arrest, Dierr stated

during a police interview that he had been walking

in the woods near Huntsville, Texas with Goodwin on

December 5 when Goodwin showed him a fence post into

which Goodwin claimed he had fired several rounds of

a .357 magnum pistol. Goodwin also told Dierr that

he had "blown someone away" with the weapon five

weeks earlier and that the body was still in the

woods. Ballistics testing revealed that all of the

projectiles and hulls recovered on or near

Tillerson's body were fired from a Smith & Wesson

.357 magnum that had been found with Atkins,

Goodwin, Dierr, and Meadows at the time of their

arrest in The Woodlands.

On January 20, 1987, Texas law

enforcement officials were notified that Goodwin and

Atkins had been arrested and were in custody in

Burlington, Iowa. During an interview in Iowa on

January 21, the Texas officers told Goodwin that

they had found the weapon used to kill Tillerson and

that it was the same weapon taken from Atkins's car

on December 4, 1986. Goodwin then admitted to having

shot Tillerson and gave a videotaped confession to

that effect. Goodwin waived extradition and was

flown back to Montgomery County that evening.

The next morning, Texas law

enforcement officials interviewed Goodwin in

Montgomery County, and he later gave a written

confession. According to Goodwin's written

confession, on the night of the murder, he and

Atkins drove by Tillerson's trailer between 8:00 and

10:00 p.m. Atkins and Goodwin had discussed the

possibility of either obtaining a loan from

Tillerson or robbing him. When Tillerson answered

the door of his trailer home, Atkins and Goodwin

entered and drew handguns. Atkins ordered Tillerson

to sit down in a chair and demanded money. When

Tillerson claimed that he had no money, Atkins

ransacked the trailer. Unable to find more than some

change, Atkins collected other items from the

trailer. Atkins then ordered Tillerson to get

dressed. Goodwin held his gun on Tillerson while

Atkins loaded the items into his car. Atkins,

Goodwin, and Tillerson left in Atkins's car, with

Atkins driving, Tillerson in the back seat, and

Goodwin in the front seat, pointing his gun at

Tillerson. Atkins eventually stopped near a wooded

area where he ordered Tillerson to get out of the

car and walk ahead of Atkins and Goodwin into the

woods. Atkins raised his gun, aimed at Tillerson and

pulled the trigger two or three times, but the

weapon did not discharge. Goodwin raised his gun,

turned his head, and fired at Tillerson. Tillerson

fell to the ground screaming. Thinking that he had

only grazed the victim, Goodwin quickly raised his

weapon and fired a second shot. When Goodwin saw

blood coming out of Tillerson's head, he ran back to

Atkins's car.

II. PROCEDURAL POSTURE

A Texas jury found Goodwin guilty

of the murder of James Douglas Tillerson and

sentenced Goodwin to death. The Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals affirmed Goodwin's conviction, see

Goodwin v. State, 799 S.W.2d 719 (Tex.Crim.App.1990),

and the United States Supreme Court denied

certiorari, see Goodwin v. Texas,

501 U.S. 1259 , 111 S.Ct. 2913, 115 L.Ed.2d

1076 (1991).

Goodwin filed two petitions for

writ of habeas corpus in state district court. The

state district court declined to conduct an

evidentiary hearing on either petition and

recommended that both applications be denied. The

state district court's orders recommending the

denial of the petitions contain no findings of fact

or conclusions of law; they merely state that "the

Court ... finds that there are no controverted,

previously unresolved facts material to the

lawfulness of the confinement of applicant." The

Court of Criminal Appeals accepted the

recommendation of the state district court as to

both petitions and summarily denied relief without

findings of fact or conclusions of law.

On February 17, 1995, Goodwin

filed a motion to proceed in forma pauperis (IFP), a

motion for appointment of counsel in federal

district court, a motion for stay of execution

pending the completion of discovery and the

submission of a formal habeas petition, and a formal

motion for discovery. Goodwin's execution was

scheduled for March 7, 1995. The district court

granted the motions to proceed IFP and for

appointment of counsel and denied the motions for

stay and discovery.

Soon thereafter, Goodwin filed

his federal petition for habeas relief and again

filed motions for discovery, for a stay of execution

pending the disposition of his habeas petition, and

for an evidentiary hearing. The district court

denied these motions. Goodwin appealed the denial of

his second motion for a stay of execution, and we

reversed the district court's order denying the stay

and ordered the district court to enter an order

staying Goodwin's execution pending determination of

the merits of the claims presented in his federal

habeas petition. The district court accordingly

granted a stay.

Four days before Goodwin's

scheduled execution date, the state answered and

filed a motion for summary judgment on all of

Goodwin's claims. Goodwin filed a cross-motion for

partial summary judgment limited to his claim that

his legal representation on direct appeal was

unconstitutionally ineffective because his counsel

failed to raise a meritorious claim that was

properly preserved at trial.

The district court denied

Goodwin's habeas petition, explaining its decision

in a memorandum opinion. The district court also

denied Goodwin's request for a certificate of

probable cause to appeal (CPC) and lifted the stay

of execution that it had previously imposed. Goodwin

requested a CPC from this court to appeal the

district court's denial of his petition for habeas

relief. We granted a stay of execution, carried the

request for CPC with the case, directed the parties

to fully brief the appeal as on the merits, and

heard full oral argument. Having concluded that a

portion of the issues that Goodwin raises on appeal

"are debatable among jurists of reason," we now

grant the CPC and rule on the merits of the appeal.

See Barefoot v. Estelle, 463 U.S. 880, 893 n. 4, 103

S.Ct. 3383, 3395 n. 4, 77 L.Ed.2d 1090 (1983) (internal

quotation marks omitted); Woods v. Johnson, 75 F.3d

1017, 1026 n. 12 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, --- U.S.

----, 117 S.Ct. 150, 136 L.Ed.2d 96 (1996).

III. STANDARD OF REVIEW

The district court did not state

that it was granting the state's motion for summary

judgment when it denied Goodwin's habeas petition.

However, the district court's reference to documents

outside of Goodwin's habeas petition demonstrates

that the court implicitly granted the motion. See

FED.R.CIV.P. 12(c) (providing that the summary

judgment procedures of Federal Rule of Civil

Procedure 56 are applicable if matters outside the

pleadings are presented to, and not excluded by, the

court).

"We review a grant of summary

judgment de novo, applying the same criteria used by

the district court in the first instance." Texas

Manufactured Housing Ass'n v. City of Nederland, 101

F.3d 1095, 1099 (5th Cir.1996), cert. denied, ---

U.S. ----, 117 S.Ct. 2497, 138 L.Ed.2d 1003 (1997).

"Summary judgment is appropriate if the record is

devoid of a genuine issue of material fact." Harris

v. Johnson, 81 F.3d 535, 539 (5th Cir.), cert.

denied, --- U.S. ----, 116 S.Ct. 1863, 134 L.Ed.2d

961 (1996) (applying summary judgment standard in §

2254 case where habeas petitioner requested a CPC

and a stay of execution). In determining whether a

genuine issue of material fact exists, we consider

the facts contained in the summary judgment record

and the reasonable inferences drawn from them in the

light most favorable to Goodwin, as he is the non-movant.

See Id. IV. ANALYSIS

Goodwin posits five arguments for

reversal of the district court's judgment denying

habeas relief: (1) Goodwin's appellate counsel

rendered unconstitutionally ineffective assistance

by failing to raise on appeal the trial court's

refusal to give the jury a requested instruction

pursuant to article 38.23 of the Texas Code of

Criminal Procedure and by failing to provide the

Texas Court of Criminal Appeals with a complete

transcript of the suppression hearing to review in

evaluating Goodwin's direct appeal; (2) he is

entitled to an evidentiary hearing on his claim that

his confessions were inadmissible at trial because

Texas law enforcement officials obtained them in

violation of the judicially created rules

established to safeguard his Fifth Amendment

privilege against compelled self-incrimination; (3)

he is entitled to an evidentiary hearing on his

claims that the state intentionally withheld from

him exculpatory impeachment evidence and knowingly

introduced false testimony during trial; (4) he was

constitutionally entitled to funds with which to

hire a rehabilitation expert to testify at the

punishment phase of his trial; and (5) section

8.04(a) of the Texas Penal Code, which prevents

voluntary intoxication from serving as a defense to

the commission of a crime, unconstitutionally

restricted the jury's consideration of evidence of

Goodwin's intoxication that would have given him a

defense to the specific intent element of capital

murder and prohibited the trial court from

submitting a constitutionally required lesser-included

offense instruction on murder.

We address each of these arguments in turn.

A. Ineffective Assistance of Counsel on Direct

Appeal

Goodwin argues that his appellate

counsel rendered unconstitutionally ineffective

assistance by (1) failing to raise on appeal the

trial court's refusal to grant Goodwin's request to

amend the jury instruction given pursuant to article

38.23 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure and

(2) failing to provide the Court of Criminal Appeals

with a complete transcript of the pretrial

suppression hearing.

A criminal defendant is

constitutionally entitled to the effective

assistance of counsel on direct appeal as of right.

See Lombard v. Lynaugh, 868 F.2d 1475, 1479 (5th

Cir.1989). In Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S.

668, 104 S.Ct. 2052, 80 L.Ed.2d 674 (1984), the

Supreme Court held that, in order to prove that

counsel afforded unconstitutionally ineffective

assistance, a petitioner must show that his

attorney's performance was deficient and that such

deficiency prejudiced the defense. Id. at 687, 104

S.Ct. at 2064. The Strickland standard applies to

claims of ineffective assistance by both trial and

appellate counsel. See United States v. Merida, 985

F.2d 198, 202 (5th Cir.1993). Goodwin has failed to

demonstrate that he received unconstitutionally

ineffective assistance of counsel on appeal because

he has not demonstrated that any deficiency in his

counsel's performance resulted in prejudice.

1. Failure to raise issue on

appeal

Goodwin argues that his appellate

counsel's performance was both deficient and

prejudicial because he failed to raise on appeal the

trial court's refusal to instruct the jury pursuant

to article 38.23 of the Texas Code of Criminal

Procedure that, if it had a reasonable doubt as to

the legality of the traffic stop in The Woodlands

that led to the arrest of Atkins, Goodwin, Dierr,

and Meadows and the seizure of the murder weapon,

then it should not consider Goodwin's confessions,

which would not have occurred but for the illegal

stop.

Article 38.23 of the Texas Code

of Criminal Procedure provides in relevant part as

follows:

No evidence obtained by an

officer or other person in violation of any

provisions of the Constitution or laws of the State

of Texas, or of the Constitution or laws of the

United States of America, shall be admitted in

evidence against the accused on the trial of any

criminal case.

In any case where the legal

evidence raises an issue hereunder, the jury shall

be instructed that if it believes, or has a

reasonable doubt, that the evidence was obtained in

violation of the provisions of this Article, then

and in such event, the jury shall disregard any such

evidence so obtained.

TEX.CRIM.PROC.CODE ANN. art.

38.23 (Vernon Supp.1998).

The record in this case evinces a

fact question bearing upon the legality of the stop.

Montgomery County Sheriff's Deputy Daniel Torres,

the officer who arrested the occupants of the car in

which Goodwin was a passenger, testified at trial

that he stopped the car because Atkins, the driver

of the car, failed to use a turn signal while

leaving the area. Glen Dierr, one of Goodwin's

fellow passengers, testified that Atkins used his

turn signal. During a search incident to the stop of

the car, officers discovered several weapons in the

car, including the .357 magnum that was later

identified as the weapon used to kill Tillerson.

On January 20, 1987, Texas Ranger

Stanley Oldham and Montgomery County Sheriff's

Detective Tracy Peterson traveled to Burlington,

Iowa, where Goodwin and Atkins were in custody on an

unrelated matter, to execute a warrant on Atkins

regarding the Tillerson murder and to interview the

two men. When Peterson and Oldham interviewed

Goodwin on January 21, they informed him that they

had recovered what appeared to be the murder weapon

used to kill Tillerson and that it was the same

weapon taken from Atkins's car on December 4.

After hearing this information,

Goodwin said, "I'm twenty-three years old and

sitting on death row." When Oldham informed him that

this was not necessarily true, Goodwin said he knew

it would be true because he had pulled the trigger.

Peterson and Oldham then obtained a videotaped

confession to the murder from Goodwin. Later that

day, Oldham and Peterson escorted Goodwin back to

Texas, arriving at 9:00 p.m. The next morning,

Peterson obtained a written confession from Goodwin.

At trial, the jury received the

following instruction regarding its duty to

disregard illegally obtained evidence:

You are instructed that our law

provides that no evidence obtained from an accused

in violation of the Constitution or laws of this

state or of the United States nor evidence derived

from the use of such evidence may be considered

against him in his trial.

A peace officer may stop and

detain a person for any offense committed within his

presence or within his view. Failure to signal a

turn is an offense. A peace officer may also

temporarily detain a person for the purpose of

investigating possible criminal behavior when he has

specific and articulable facts which, in light of

his experience and personal knowledge taken together

with rational inferences from those facts, would

constitute a reasonable suspicion that some crime

has been or is about to be committed. Where the

facts relied upon by the police officer in

temporarily detaining a person are as consistent

with innocent activity as with criminal activity, a

detention based on those facts is unlawful.

You are therefore instructed that

if you find from the evidence beyond a reasonable

doubt, when Deputy Daniel Torres stopped and

detained the vehicle and the occupants of the

vehicle in which the defendant was a passenger that

the driver failed to signal a turn, or that Deputy

Torres, at the time of the stop and detention of the

vehicle and its occupants, had specific and

articulable facts which, in light of his experience

and personal knowledge taken together with rational

inferences from those facts, would constitute a

reasonable suspicion that some crime had been or was

about to be committed, then you may consider the

weapons and other items seized from said vehicle,

and any testimony relating to their seizure, testing

by firearms examiners, or identification as the

murder weapon.

Unless you so find beyond a

reasonable doubt, or if you have a reasonable doubt

thereof, you will not consider for any purpose the

weapons and other items seized from said vehicle,

and any testimony relating to their seizure, testing

by firearms examiners, or identification as the

murder weapon.

Defense counsel requested that

the words "and the confessions of the accused" be

added at the end of the last two paragraphs on the

ground that any illegality in the underlying search

that uncovered the .357 magnum would have tainted

Goodwin's confessions. The trial court denied

counsel's request.

Goodwin was entitled to an

article 38.23 instruction if the trial evidence

raised a factual issue concerning whether evidence

was obtained in violation of the U.S. Constitution,

other federal law, the Texas Constitution, or other

Texas law. See TEX.CRIM.PROC.CODE ANN. § 38.23

(Vernon Supp.1998); Thomas v. State, 723 S.W.2d 696,

707 (Tex.Crim.App.1986). Because the conflicting

trial testimony created a fact issue concerning

Torres's right to stop the vehicle, the trial court

appropriately granted an article 38.23 instruction

with respect to the murder weapon. See Stone v.

State, 703 S.W.2d 652, 655 (Tex.Crim.App.1986)

(holding that a fact issue arose concerning a peace

officer's right to stop a vehicle due to conflicting

testimony between the officer, who stated he stopped

the appellant's vehicle for erratic driving, and the

testimony of the appellant and another witness that

the appellant was driving in a prudent manner).

We assume without deciding that

Goodwin's confessions were not sufficiently

attenuated from the traffic stop so as to render any

illegality of the traffic stop irrelevant to the

admissibility of the confessions. In other words, we

assume without deciding that Goodwin was entitled to

an article 38.23 jury instruction regarding his

confessions because, in the event that the traffic

stop was illegal, the confessions were tainted by

such illegality.

We likewise assume that the trial court's refusal to

provide the requested article 38.23 instruction

would have required reversal of Goodwin's conviction

on direct appeal and a new trial.

Assuming that the trial court's

refusal to provide the requested article 38.23

instruction would have entitled Goodwin to reversal

of his conviction on direct appeal, Goodwin

nonetheless cannot establish that the failure of his

appellate counsel to raise this issue on direct

appeal resulted in prejudice.

"The essence of an ineffective assistance claim is

that counsel's unprofessional errors so upset the

adversarial balance between defense and prosecution

that the trial was rendered unfair and the verdict

rendered suspect." Kimmelman v. Morrison, 477 U.S.

365, 374, 106 S.Ct. 2574, 2582, 91 L.Ed.2d 305

(1986).

We are convinced that the trial

court's failure to provide the jury with an article

38.23 instruction regarding Goodwin's confessions in

no way rendered the trial unfair or the verdict

suspect. As such, the failure of Goodwin's appellate

counsel to present this issue on direct appeal was

not prejudicial because it did not "undermine[ ] the

reliability of the result of the proceeding."

Strickland, 466 U.S. at 693, 104 S.Ct. at 2067.

Prior to trial, Goodwin moved to

suppress his confessions on the ground that they

were tainted by the illegal stop and search of

Atkins's automobile in The Woodlands. He based this

motion in part on the argument that Atkins had not

failed to use his turn signal and thus that no basis

existed for the stop. The state district court

denied the motion to suppress and specifically found

that Atkins had not used his turn signal. Because

Goodwin alleges no defect in this fact-finding or

the procedure used at the suppression hearing to

obtain it, we accord the court's conclusion that

Atkins did not use his blinker a presumption of

correctness. See 28 U.S.C. 2254(d) (1994);

Harris, 81 F.3d at 539.

Goodwin has not argued that any

factual issues other than the issue of whether

Atkins used his turn signal bear upon the legality

of the traffic stop and the subsequent search that

resulted in the discovery and seizure of the murder

weapon. Goodwin does not dispute that the traffic

stop was perfectly legal if in fact Atkins failed to

use his blinker, nor can he do so. So long as a

traffic law infraction that would have objectively

justified the stop had taken place, the fact that

the police officer may have made the stop for a

reason other than the occurrence of the traffic

infraction is irrelevant for purposes of the Fourth

Amendment and comparable Texas law. See Whren v.

United States,

517 U.S. 806 , ----, 116 S.Ct. 1769, 1774, 135

L.Ed.2d 89 (1996) (concluding that a "pretextual"

traffic stop for a minor traffic infraction was

constitutional because " 'the fact that the officer

does not have the state of mind which is

hypothecated by the reasons which provide the legal

justification for the officer's action does not

invalidate the action taken as long as the

circumstances, viewed objectively, justify that

action' " (quoting Scott v. United States, 436 U.S.

128, 138, 98 S.Ct. 1717, 1723, 56 L.Ed.2d 168

(1978))); Crittenden v. State, 899 S.W.2d 668, 674 (Tex.Crim.App.1995)

("[A]n objectively valid traffic stop is not

unlawful under Article I, § 9 [of the Texas

Constitution, a provision analogous to the Fourth

Amendment of the U.S. Constitution], just because

the detaining officer had some ulterior motive for

making it."). Because the state district court

concluded that the state established by a

preponderance of the evidence that Atkins did not

use his blinker,

the introduction of Goodwin's confessions was fully

consistent with the Fourth Amendment exclusionary

rule. See United States v. Chavis, 48 F.3d 871, 872

(5th Cir.1995) (holding that the state bears the

burden of proving that a warrantless stop and search

is reasonable in order for evidence obtained

therefrom to be admissible); United States v.

Finefrock, 668 F.2d 1168, 1170 (10th Cir.1982)

(holding that the government must prove the

reasonableness of a warrantless search or seizure by

a preponderance of the evidence); United States v.

Collins, 863 F.Supp. 165, 169 n. 2 (S.D.N.Y.1994)

("[T]he government must show by a preponderance of

the evidence that the warrantless search does not

contravene the Fourth Amendment."); cf. United

States v. Matlock, 415 U.S. 164, 178 n. 14, 94 S.Ct.

988, 996 n. 14, 39 L.Ed.2d 242 (1974) ("[T]he

controlling burden of proof at suppression hearings

should impose no greater burden than proof by a

preponderance of the evidence.").

We simply cannot conclude that

the trial court's failure to give the jury an

opportunity to wholly disregard the confessions if

it believed, or had a reasonable doubt, that they

were obtained unlawfully--after the court had in

effect found during the pretrial suppression hearing

by a preponderance of the evidence that the

confessions were obtained in compliance with the

Fourth Amendment and analogous Texas law--rendered "the

result of the trial unreliable or the proceeding

fundamentally unfair." Lockhart v. Fretwell, 506

U.S. 364, 372, 113 S.Ct. 838, 844, 122 L.Ed.2d 180

(1993). Indeed, had the trial court given the

requested article 38.23 instruction in this case,

the reliability of the trial may very well have

decreased.

As the Supreme Court noted in

Stone v. Powell,

428 U.S. 465 , 96 S.Ct. 3037, 49 L.Ed.2d 1067

(1976), application of the Fourth Amendment

exclusionary rule "deflects the truthfinding process

and often frees the guilty" by excluding "reliable

and ... probative information bearing on the guilt

or innocence of the defendant." Id. at 490, 96 S.Ct.

at 3050.

The Texas exclusionary rule has

an even greater propensity for deflecting the

truthfinding process of the trial when applied to

evidence arguably obtained through an illegal search

or seizure because it requires the jury to disregard

such evidence, regardless of how probative, if the

jury "believes, or has a reasonable doubt, that the

evidence" was unlawfully obtained.

TEX.CRIM.PROC.CODE ANN. § 38.23(a) (Vernon Supp.1998).

Thus, the failure of Goodwin's appellate counsel to

raise this issue on appeal was not

unconstitutionally prejudicial.

Goodwin contends that he has

established Strickland prejudice if "there is a 'reasonable

probability' that the omitted article 38.23

instruction claim would have caused a reversal on

direct appeal had it been raised by [his] appellate

counsel." We disagree.

As an initial matter, the Supreme

Court has indicated that "an analysis focusing

solely on mere outcome determination, without

attention to whether the result of the proceeding

was fundamentally unfair or unreliable, is defective."

Fretwell, 506 U.S. at 369, 113 S.Ct. at 842.

Furthermore, the law of the Supreme Court and this

circuit lead us to conclude that the presence or

absence of prejudice, both with respect to claims of

ineffective assistance of counsel at the trial and

appellate levels, hinges upon the fairness of the

trial and the reliability of the judgment of

conviction resulting therefrom.

In Evitts v. Lucey, 469 U.S. 387,

105 S.Ct. 830, 83 L.Ed.2d 821 (1985), the Supreme

Court indicated that a criminal defendant's right to

effective assistance of counsel on his first appeal

as of right stems from the fact that, when a state

chooses to create appellate courts, appellate review

becomes " 'an integral part of the ... system for

finally adjudicating the guilt or innocence of a

defendant.' " Id. at 393, 105 S.Ct. at 834 (quoting

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12, 18, 76 S.Ct. 585,

590, 100 L.Ed. 891 (1956)).

The appellate process exists

solely for the purpose of correcting errors that

occurred at the trial court level. See id. at 396,

105 S.Ct. at 836 ("In bringing an appeal as of right

from his conviction, a criminal defendant is

attempting to demonstrate that the conviction, with

its consequent drastic loss of liberty, is unlawful.").

As such, we conclude that the right to effective

assistance of counsel, both at the trial and

appellate level, " 'is recognized not for its own

sake, but because of the effect that it has on the

ability of the accused to receive a fair trial.' "

Fretwell, 506 U.S. at 369, 113 S.Ct. at 842 (quoting

United States v. Cronic, 466 U.S. 648, 658, 104 S.Ct.

2039, 2046, 80 L.Ed.2d 657 (1984)).

This court's decision in Ricalday

v. Procunier, 736 F.2d 203 (5th Cir.1984), supports

our conclusion that the presence or absence of

Strickland prejudice as a result of

unconstitutionally deficient performance of counsel

at either the trial or appellate level hinges upon

the fairness of the trial and the reliability of its

outcome. In Ricalday, the habeas petitioner's

counsel failed to object to the trial court's

instruction of the jury regarding an unindicted

offense and did not raise this issue on appeal. See

id. at 205.

Pursuant to the Texas Penal

Code's definition of the offense of murder, the

trial court instructed the jury that it could

convict the petitioner of murder either if he " 'intentionally

or knowingly cause[d] the death of an individual' "

or if he " 'intend[ed] to cause serious bodily

injury and commit[ed] an act clearly dangerous to

human life that cause[d] the death of an

individual.' " Id. (quoting TEX.PEN.CODE ANN. §

19.02 (Vernon 1974)). However, the indictment only

charged the petitioner with "intentionally or

knowingly caus[ing] the death of an individual." Id.

(alteration in original). Under Texas law,

conviction of an unindicted offense constituted

"fundamental" error requiring reversal. See id. at

207 (citing Bentacur v. State, 593 S.W.2d 686 (Tex.Crim.App.1980)).

The court concluded that the

failure of the petitioner's counsel to object to the

trial court's inclusion of the unindicted offense in

the jury charge was not prejudicial because there

was "no reasonable probability that the factfinder

would have had a reasonable doubt concerning the

petitioner's intent to kill." Id. at 209. The court

then rejected the habeas petitioner's claim of

ineffective assistance of appellate counsel: "Because

the error at the appellate stage stemmed from the

error at trial, if there was no prejudice from the

trial error, there was also no prejudice from the

appellate error." Id. at 208.

The court therefore concluded "that

the proceedings were not fundamentally unfair and

that their result, and the finding of guilt, are

reliable." Id. at 209 n. 6 (emphasis added). We have

applied Ricalday's sound analysis in other cases as

well. See McCrae v. Blackburn, 793 F.2d 684, 688

(5th Cir.1986) (concluding that appellate counsel's

failure to raise an issue on appeal was not

prejudicial because the petitioner could not

demonstrate a reasonable probability that raising

the issue would have ultimately resulted in the

trial court's imposition of a different sentence);

Hamilton v. McCotter, 772 F.2d 171, 182 (5th

Cir.1985) (rejecting a claim of ineffective

assistance of appellate counsel because "the state

record reflect[ed] that the proceedings were

fundamentally fair, that their result and the

finding of guilt are reliable, and that no breakdown

of the adversarial process rendered them otherwise"

(emphasis added)).

Goodwin relies on Duhamel v.

Collins, 955 F.2d 962 (5th Cir.1992) for the

proposition that, "[i]n order to prove that his

appellate attorney's alleged error was prejudicial,

[a federal habeas petitioner] must show that the

neglected claim would have had a reasonable

probability of success on appeal." Id. at 967. While

Goodwin does not rely upon it, we acknowledge that,

in another Fifth Circuit case, Sharp v. Puckett, 930

F.2d 450 (5th Cir.1991), the court utilized a

similar prejudice analysis in disposing of a habeas

petitioner's claim of ineffective assistance of

appellate counsel. See id. at 453 (" 'The [petitioner]

must show that there is a reasonable probability

that, but for counsel's unprofessional errors, the

result of the [appeal] would have been different." (quoting

Strickland, 466 U.S. at 694, 104 S.Ct. at 2068) (alterations

in original)).

We note as an initial matter that

Duhamel and Sharp's focus on the outcome of the

appeal is inconsistent with the analysis advanced in

Ricalday. We are therefore bound to follow Ricalday,

an earlier panel decision, because "[i]t has long

been a rule of this court that no panel of this

circuit can overrule a decision previously made by

another." Ryals v. Estelle, 661 F.2d 904, 906 (5th

Cir. Nov. 1981).

Additionally, Duhamel and Sharp

are both pre-Fretwell decisions. Fretwell makes

clear that their limited focus on "mere outcome

determination" at the appellate level is "defective."

Fretwell, 506 U.S. at 369, 113 S.Ct. at 842.

Fretwell indicates that we must determine the

presence or absence of prejudice based upon the

fairness of the proceeding and the reliability of

its result. See id. at 369, 113 S.Ct. at 842.

To the extent that the appellate

process is merely a vehicle for correcting errors at

trial, the fairness and reliability of an appeal are

necessarily functions of the fairness and

reliability of the trial. Because the trial court's

refusal to provide the jury with an article 38.23

instruction regarding his confessions did not render

Goodwin's trial fundamentally unfair nor the

conviction and sentence resulting therefrom

unreliable, Goodwin was not prejudiced by his

appellate counsel's failure to raise this issue on

appeal. Therefore, the district court properly

concluded that he is not entitled to habeas relief

on this claim.

2. Failure to provide entire

record to appellate court

Goodwin argues that he was denied

a meaningful appeal due to his appellate counsel's

failure to provide the Texas Court of Criminal

Appeals with a full transcript of his pretrial

suppression hearing to review on direct appeal.

Goodwin's appellate counsel apparently neglected to

have two days of the suppression hearing transcribed

and therefore did not supply the Court of Criminal

Appeals with a complete transcript of the

suppression hearing. The missing portion of the

transcript contained the testimony of Atkins and

Dierr indicating that Atkins had used his turn

signal prior to the traffic stop in The Woodlands.

Goodwin contends that his

appellate counsel's failure to submit a complete

transcript of the pretrial suppression hearing

violated his right to effective assistance of

appellate counsel because the Court of Criminal

Appeals was thereby precluded from reviewing all of

the evidence pertaining to the legality of the

traffic stop and the propriety of the trial court's

denial of Goodwin's motion to suppress. We disagree.

Under Texas law, the trial court

is the sole fact-finder and judge of the credibility

of the witnesses as well as the weight to be given

their testimony at a hearing on a motion to suppress.

See Romero v. State, 800 S.W.2d 539, 543 (Tex.Crim.App.1990);

Hawkins v. State, 628 S.W.2d 71, 75 (Tex.Crim.App.1982).

Accordingly, the trial court may choose to believe

or disbelieve any or all of a witness's testimony.

See Luckett v. State, 586 S.W.2d 524, 527 (Tex.Crim.App.1979).

On appeal, the Court of Criminal

Appeals cannot disturb the trial court's findings so

long as they are supported by the record. See Green

v. State, 615 S.W.2d 700, 707 (Tex.Crim.App.1980).

If the Court of Criminal Appeals concludes that the

record supports the trial court's factual

conclusions, its review is limited to a

determination of "whether the trial court improperly

applied the facts to the law." Johnson v. State, 698

S.W.2d 154, 159 (Tex.Crim.App.1985).

Even if the Court of Criminal

Appeals had been privy to the testimony of Atkins

and Dierr, it would have been compelled to accept

the trial court's determination that Atkins failed

to use his blinker because the record contained

Officer Torres's testimony to that effect. The fact

that the Court of Criminal Appeals might have

considered the testimony of Atkins and Dierr more

credible than that of Officer Torres would have been

entirely irrelevant to the court's review of the

trial court's denial of the motion to suppress. See

Green, 615 S.W.2d at 707; Luckett, 586 S.W.2d at

527.

Goodwin therefore cannot

establish that his appellate counsel's failure to

provide the Court of Criminal Appeals with a full

transcript of the suppression hearing in any way

prejudiced him. Accordingly, he has not demonstrated

that he is entitled to habeas relief on this basis.

See Strickland, 466 U.S. at 687, 104 S.Ct. at 2064.

B. Violation of Judicially

Created Safeguards of the Fifth Amendment Privilege

Against Self-Incrimination

Goodwin argues that the district

court erred by failing to conduct an evidentiary

hearing on his claim that the admission of his

confessions as evidence at trial violated the

judicially created rules established to safeguard

his Fifth Amendment privilege against compelled self-incrimination.

In support of his claim, Goodwin offers his

affidavit, which states that, shortly after he was

arrested in Burlington, Iowa, Goodwin told police

that he did not wish to answer any questions in the

absence of counsel. Goodwin contends that his

confessions were therefore inadmissible at trial

because they are the product of interrogation

initiated by Texas law enforcement officials after

Goodwin's request for the assistance of counsel

during custodial interrogation.

1. Exhaustion of state

remedies and procedural default doctrine

The district court appears to

have based its denial of this portion of Goodwin's

petition for habeas relief on its belief that

Goodwin did not assert the claim in state court. The

district court's opinion states the following:

This is not a proper complaint

for habeas corpus review. Goodwin's affidavit comes

seven years after the incident. He was uniquely

aware of the alleged mistreatment before trial and

should have informed his attorney then. This issue

could have been litigated at the trial and is,

therefore, inappropriate to raise here for the first

time.

The district court mistakenly

concluded that Goodwin asserted his current Fifth

Amendment claim for the first time in his federal

habeas petition. Goodwin presented the Fifth

Amendment argument that he now asserts for the first

time in his second state habeas petition. Therefore,

he has not failed to exhaust his state remedies with

respect to this claim, and the state conceded as

much at the district court level. See Nobles v.

Johnson, 127 F.3d 409, 420 (5th Cir.1997) ("To have

exhausted his state remedies, a habeas petitioner

must have fairly presented the substance of his

claim to the state courts.").

Moreover, the state has not

argued, either at the district court level or on

appeal, that Goodwin's Fifth Amendment claim is

procedurally barred on the basis that he failed to

present the claim until his second state habeas

petition or on any other basis. In its response to

Goodwin's second state habeas petition, the state

likewise did not argue that Goodwin had procedurally

defaulted his claim by failing to assert it earlier.

Given that the state has not seen

fit to argue in this court, the district court, or

even its own courts that Goodwin's Fifth Amendment

claim is procedurally defaulted, we would advance no

interest in federalism or comity by raising the

issue ourselves. We therefore decline to do so and

proceed to the merits of Goodwin's Fifth Amendment

claim. See Trest v. Cain, --- U.S. ----, ----, 118

S.Ct. 478, 480, 139 L.Ed.2d 444 (1997) (holding that

a court of appeals reviewing a district court's

habeas corpus decision is not required to raise sua

sponte the petitioner's potential procedural default).

2. Goodwin's entitlement to an

evidentiary hearing

"When there is a 'factual

dispute, [that,] if resolved in the petitioner's

favor, would entitle [her] to relief and the state

has not afforded the petitioner a full and fair

evidentiary hearing,' a federal habeas corpus

petitioner is entitled to discovery and an

evidentiary hearing." Perillo v. Johnson, 79 F.3d

441, 444 (5th Cir.1996) (quoting Ward v. Whitley, 21

F.3d 1355, 1367 (5th Cir.1994)) (alterations in

original).

We conclude that Goodwin has

satisfied the above standard and is therefore

entitled to an evidentiary hearing to resolve the

factual issue of whether Goodwin informed the

Burlington police upon being taken to the Burlington

police station that he did not wish to be

interrogated in the absence of counsel. If Goodwin

so informed the Burlington police, then his

confessions later obtained through interrogation

initiated by Texas law enforcement officers were

inadmissible on Fifth Amendment grounds, and the

admission of those confessions was not harmless

error. We further conclude that the fact-finding

procedure utilized by the state district court in

resolving this factual issue was inadequate to

afford Goodwin a full and fair hearing. As such,

Goodwin is entitled to an evidentiary hearing on his

Fifth Amendment claim.

a. Fifth Amendment law

The Fifth Amendment guarantees

that "[n]o person ... shall be compelled in any

criminal case to be a witness against himself."

U.S. Const. amend. V, The Fifth Amendment

privilege against self-incrimination is "protected

by the Fourteenth Amendment against abridgment by

the States." Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1, 6,

84 S.Ct. 1489, 1492, 12 L.Ed.2d 653 (1964). In

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 86 S.Ct. 1602, 16

L.Ed.2d 694 (1966), the Supreme Court observed that

"the right to have counsel present ... [during

custodial] interrogation is indispensable to the

protection of the Fifth Amendment privilege." Id. at

469, 86 S.Ct. at 1625. In order to fully safeguard

the privilege, the Court held that, "[i]f the

individual [under interrogation] states that he

wants an attorney, the interrogation must cease

until an attorney is present." Id. at 474, 86 S.Ct.

at 1628.

As a corollary to the

prophylactic rule adopted in Miranda, the Court held

in Edwards v. Arizona, 451 U.S. 477, 101 S.Ct. 1880,

68 L.Ed.2d 378 (1981), that, once the accused

asserts this Fifth Amendment right to counsel

and thereby "expresse[s] his desire to deal with the

police only through counsel, [he] is not subject to

further interrogation by the authorities until

counsel has been made available to him, unless the

accused himself initiates further communication,

exchanges, or conversations with the police." Id. at

484-85, 101 S.Ct. at 1884-85; see also United States

v. Carpenter, 963 F.2d 736, 739 (5th Cir.1992). "If

the police do subsequently initiate an encounter in

the absence of counsel (assuming there has been no

break in custody), the suspect's statements are

presumed involuntary and therefore inadmissible as

substantive evidence at trial, even where the

suspect executes a waiver and his statements would

be considered voluntary under traditional

standards." McNeil v. Wisconsin,

501 U.S. 171 , 177, 111 S.Ct. 2204, 2208, 115

L.Ed.2d 158 (1991).

In Arizona v. Roberson, 486 U.S.

675, 108 S.Ct. 2093, 100 L.Ed.2d 704 (1988), the

Court made clear that the Edwards rule is not

offense specific.

See id. at 682-84, 108 S.Ct. 2098-2100; see also

McNeil, 501 U.S. at 177, 111 S.Ct. at 2208;

Carpenter, 963 F.2d at 739. Once a suspect invokes

his Fifth Amendment right to counsel with respect to

one offense, law enforcement officials may not

reapproach him regarding any offense unless counsel

is present. See McNeil, 501 U.S. at 177, 111 S.Ct.

at 2208; Roberson, 486 U.S. at 682-84, 687, 108 S.Ct.

at 2098-2100, 2101; Carpenter, 963 F.2d at 739;

United States v. Cooper, 949 F.2d 737, 741 (5th

Cir.1991).

This is true even when different

law enforcement authorities who may be unaware of

the suspect's prior invocation of his Fifth

Amendment right to counsel reapproach the suspect

regarding a different offense. See Roberson, 486

U.S. at 687, 108 S.Ct. at 2101 ("[W]e attach no

significance to the fact that the officer who

conducted the second interrogation did not know that

respondent had made a request for counsel.");

Minnick v. Mississippi, 498 U.S. 146, 148-49, 155,

111 S.Ct. 486, 488-89, 112 L.Ed.2d 489 (1990)

(holding that statements of the petitioner derived

from reinitiation of custodial interrogation by a

county deputy sheriff were inadmissible because the

petitioner had previously invoked his Fifth

Amendment right to counsel during interrogation by

FBI agents); Cooper, 949 F.2d at 741 ("Because the

Fifth Amendment right is not offense specific, the

Edwards rule applies even when the interrogation is

based on different offenses or is conducted by

different law enforcement authorities."); cf. United

States v. Webb, 755 F.2d 382, 389-90 (5th Cir.1985)

(holding that FBI agents obtained the defendant's

confession in violation of Edwards where the

defendant had previously invoked his right to

counsel and a state official erroneously informed

the FBI that the defendant had on his own initiative

requested the opportunity to make a statement to FBI

agents).

Proper application of the above

legal principles to Goodwin's Fifth Amendment claim

requires a synopsis of the factual circumstances

surrounding the confessions that Goodwin made at the

behest of Texas law enforcement officers. On January

17, 1987, Goodwin was arrested in Burlington, Iowa

for first degree burglary and going armed with

intent.

Burlington police officers took Goodwin to the

Burlington police station, where he was held in

custody through January 21.

On January 21, Texas law

enforcement officials interviewed Goodwin. During

the interview, Goodwin signed a waiver of rights

form, and subsequently provided the Texas law

enforcement authorities with a videotaped confession.

That evening, Goodwin flew back to Texas in the

custody of Texas law enforcement officials. The next

morning, Texas law enforcement officials brought

Goodwin before a magistrate who issued a

magistrate's warning and set Goodwin's bond. A law

enforcement officer later read Goodwin his rights

again, and Goodwin again agreed to waive them. He

then provided a written confession. He also made

incriminating oral statements identifying the

bayonet stolen from Tillerson and the gun used by

Atkins during the robbery and murder.

Goodwin contends that he invoked

his Fifth Amendment right to counsel following his

arrest in Burlington. In support of this contention,

he offers his own affidavit, which he submitted

along with his federal habeas petition and his

second state habeas petition. Goodwin's affidavit

states that, shortly after his arrest, a Burlington

police officer asked Goodwin to sign a form waiving

his Miranda rights. According to his affidavit,

Goodwin refused to do so and informed the officer

that he did not wish to answer any questions outside

the presence of an attorney.

If what Goodwin states in his

affidavit is true, his subsequent purported waivers

of this Fifth Amendment right to counsel prior to

interrogation by Texas authorities were

presumptively invalid even though the Texas

authorities informed Goodwin of his Miranda rights

prior to each waiver, and his confessions would be

inadmissible on this basis. See Roberson, 486 U.S.

at 682-84, 687, 108 S.Ct. at 2098-99, 2101; United

States v. Cruz, 22 F.3d 96, 98 (5th Cir.1994) ("

'[A] valid waiver of that right [to have counsel

present during custodial interrogation] cannot be

established by showing only that [the accused]

responded to further police-initiated custodial

interrogation even if [the accused] has been advised

of his rights.' " (quoting Edwards, 451 U.S. at 484,

101 S.Ct. at 1884)) (all alterations except second

in original).

b. Harmless error

Although admission of Goodwin's

confessions constituted constitutional error under

the factual scenario advanced by Goodwin, such error

cannot provide a ground for habeas relief, and thus

cannot provide a basis for an evidentiary hearing,

if the error was harmless. See Brecht v. Abrahamson,

507 U.S. 619, 622-23, 113 S.Ct. 1710, 1713-14, 123

L.Ed.2d 353 (1993) (observing that habeas relief

need not be granted when constitutional error is

harmless); Perillo, 79 F.3d at 444 (noting that an

evidentiary hearing is required only if the

petitioner establishes the existence of "a factual

dispute, that, if resolved in the petitioner's

favor, would entitle her to relief" (internal

quotation marks and brackets omitted)).

The Supreme Court has held that "trial

error"--that is, error that " 'occur[s] during the

presentation of the case to the jury' "--"is

amenable to harmless-error analysis because it 'may

... be quantitatively assessed in the context of

other evidence presented in order to determine [the

effect it had on the trial].' " See Brecht, 507 U.S.

at 629, 113 S.Ct. at 1716 (quoting Arizona v.

Fulminante, 499 U.S. 279, 307-08, 111 S.Ct. 1246,

1263-64, 113 L.Ed.2d 302 (1991)) (alterations in

original). The admission of confessions obtained in

violation of Edwards and its progeny constitutes

trial error, and is therefore amenable to harmless

error analysis. See United States v. Cannon, 981

F.2d 785, 789 n. 3 (5th Cir.1993) ("A harmless-error

analysis may be performed to examine the effect of

an Edwards violation."); United States v. Webb, 755

F.2d 382, 392 (5th Cir.1985) (applying harmless-error

analysis to statements admitted in violation of

Edwards ).

The harmless-error standard applicable in

conducting habeas review requires the granting of

habeas relief on the basis of constitutional trial

error only if the error " 'had substantial and

injurious effect or influence in determining the

jury's verdict.' " Brecht, 507 U.S. at 620, 113 S.Ct.

at 1712 (quoting Kotteakos v. United States, 328

U.S. 750, 776, 66 S.Ct. 1239, 1253, 90 L.Ed. 1557

(1946)).

If in fact Goodwin invoked his

Fifth Amendment right to counsel upon his arrival at

the Burlington police station, then the state

district court improperly admitted Goodwin's

videotaped confession, his written confession, and

his incriminating statements identifying the bayonet

stolen from Tillerson and the gun used by Atkins

during the robbery and murder. We are convinced that

the admission of this evidence, if improper, "had

substantial and injurious effect or influence in

determining the jury's verdict." Id. at 623, 113

S.Ct. at 1713 (internal quotation marks omitted).

While the state presented a

substantial amount of other evidence against

Goodwin, including the testimony of Dierr that

Goodwin told him that he shot someone in the woods

and ammunition found at the site of Goodwin's

confession to Dierr that was fired from the murder

weapon, Goodwin's statements doubtless had a

tremendous impact on the jury.

Goodwin's written confession

lengthily recounts how he and Atkins held Tillerson

at gunpoint while they searched Tillerson's trailer

for money, how they began taking items from the

trailer, how they drank all of Tillerson's beer

while they were there, how they made Tillerson get

dressed and go with them in Atkins's car to the

woods, and how Goodwin killed Tillerson. Goodwin's

videotaped confession contains similar factual

detail. Moreover, Goodwin's statements identifying

the weapon used by Atkins and the bayonet stolen

from Tillerson are highly probative of his guilt.

"A confession is like no other

evidence." Fulminante, 499 U.S. at 296, 111 S.Ct. at

1257. It "is probably the most probative and

damaging evidence that can be admitted against [a

criminal defendant]." Bruton v. United States, 391

U.S. 123, 139, 88 S.Ct. 1620, 1629, 20 L.Ed.2d 476

(1968) (White, J., dissenting). "While some

statements by a defendant may concern isolated

aspects of the crime or may be incriminating only

when linked to other evidence, a full confession in

which the defendant discloses the motive for and

means of the crime may tempt the jury to rely upon

that evidence alone in reaching its decision."

Fulminante, 499 U.S. at 296, 111 S.Ct. at 1257.

The possibility that the jury

focused solely on Goodwin's confessions in this case

is enhanced by the fact that the prosecution stated

in closing argument that Goodwin's confessions were

the "only evidence" that Goodwin killed Tillerson

"in the course of committing kidnapping [or] robbery,"

a fact that the state had to prove beyond a

reasonable doubt in order to support Goodwin's

conviction for capital murder. See TEX.PEN.CODE ANN.

§ 19.03(a)(2) (Vernon 1994). We therefore cannot say

that the state district court's admission of

Goodwin's two confessions, coupled with its

admission of his other highly incriminating

statements of identification, constituted harmless

error.

Because any error the state

district court committed in admitting Goodwin's

confessions and other incriminating statements was

not harmless, Goodwin has established the existence

of a fact issue that, if resolved in his favor,

would entitle him to habeas relief.

We turn now to the issue of whether the state court

afforded him a full and fair hearing for the

resolution of this fact issue.

3. Full and fair hearing in

state court

As demonstrated above, if the

factual dispute as to whether Goodwin ever invoked

his Fifth Amendment right to counsel is resolved in

Goodwin's favor, he is entitled to habeas relief.

For the reasons that follow, we conclude that the

state did not afford Goodwin a full and fair hearing

on this factual issue and that he is therefore

entitled to an evidentiary hearing in federal

district court to resolve it.

"There cannot even be the

semblance of a full and fair hearing unless the

state court actually reached and decided the issues

of fact tendered by the defendant." Townsend v. Sain,

372 U.S. 293, 313-14, 83 S.Ct. 745, 756-57, 9 L.Ed.2d

770 (1963). As such, when the state court did not

resolve a fact issue that would entitle the

petitioner to relief if resolved in his favor, the

petitioner is entitled to an evidentiary hearing on

the issue. See id. at 313, 83 S.Ct. at 756; Blackmon

v. Scott, 22 F.3d 560, 567 & n. 28 (5th Cir.1994) (concluding

that an evidentiary hearing on factual issues

underlying a habeas petitioner's federal claims was

required because the state court made no fact-findings

on the issues).

In determining whether the state

court reached the merits of a factual issue, the

district court may, in appropriate circumstances,

imply fact-findings from the state court's

disposition of a federal claim that turns on the

factual issue. In Townsend, the Supreme Court

observed:

If the state court has decided

the merits of the claim but has made no express

findings, it may still be possible for the District

Court to reconstruct the findings of the state trier

of fact, either because his view of the facts is

plain from his opinion or because of other indicia.

Townsend, 372 U.S. at 314, 83

S.Ct. at 757. The Court went on to state that

the coequal responsibilities of

state and federal judges in the administration of

federal constitutional law are such that we think

the district judge may, in the ordinary case in

which there has been no articulation, properly

assume that the state trier of fact applied correct

standards of federal law to the facts in the absence

of evidence ... that there is reason to suspect that

an incorrect standard was in fact applied.

Id. at 314-15, 83 S.Ct. at

757-58; Dempsey v. Wainwright, 471 F.2d 604, 606

(5th Cir.1973) ("[I]f the state court did not

articulate the constitutional standards applied, the

district court may presume that the state court

applied correct findings, in the absence of evidence

that an incorrect standard was applied.").

In this case, neither the state

district court nor the Court of Criminal Appeals

made any express findings of fact regarding whether

Goodwin requested the assistance of counsel during

custodial interrogation when first taken to the

Burlington police station. Furthermore, we conclude

that neither court made any implicit fact-findings

on this issue. In addressing Goodwin's habeas

petition, the state courts made no conclusions of

law regarding Goodwin's Fifth Amendment claim (or

any of his other claims) from which we could infer a

factual finding that Goodwin did not refuse police

interrogation in the absence of an attorney when

first taken to the Burlington police station.

Rather, the district court

recommended in a two-page order containing no legal

analysis of Goodwin's claims that Goodwin's request

for relief be denied, and the Court of Criminal

Appeals accepted the recommendation in an even more

summary fashion. A conclusion that the state courts'

summary denial of Goodwin's petition for habeas

corpus relief implies a finding that Goodwin never

invoked his Fifth Amendment right to counsel finds

no support in the Supreme Court's jurisprudence and

is contrary to this circuit's treatment of implied

fact-findings.

In the circumstances in which the

Supreme Court has held that a state court has made

implied findings of fact, the state court's written

disposition of the claim in question has contained

explicit conclusions of law. For example, in

Marshall v. Lonberger, 459 U.S. 422, 103 S.Ct. 843,

74 L.Ed.2d 646 (1983), the Court determined that a

state trial court's legal conclusion that a criminal

defendant's guilty plea was admissible into evidence

implied a factual determination that the defendant's

testimony that he had never been given an

opportunity to review the indictment for the charged

offense lacked credibility.

The Court observed that "[t]he

trial court's ruling allowing the record of

conviction to be admitted in evidence ... is

tantamount to a refusal to believe the testimony of

respondent." Id. at 434, 103 S.Ct. at 850. However,

the trial court's ruling that the confession was

admissible contained an express legal conclusion

that "the defendant intelligently and voluntarily

entered his plea of guilty." Id. at 429, 103 S.Ct.

at 847 (internal quotation marks omitted).

Similarly, in LaVallee v. Delle

Rose, 410 U.S. 690, 93 S.Ct. 1203, 35 L.Ed.2d 637

(1973), the court held that the trial court's legal

conclusion that a criminal defendant's "confessions

to the police and district attorney were, in all

respects, voluntary and legally admissible in

evidence at the trial" implied a fact-finding by the

trial court that the defendant's testimony that his

confessions resulted from police coercion lacked

credibility. Id. at 691, 93 S.Ct. at 1203.

The Court stated, "Although it is

true that the state trial court did not specifically

articulate its credibility findings, it can scarcely

be doubted from its written opinion that

respondent's factual contentions were resolved

against him." Id. at 692, 93 S.Ct. at 1204. In both

of the above cases, the state court had made an

express legal conclusion from which the reviewing

federal court could accurately reconstruct the

factual determinations that formed the basis of the

state court's legal conclusion.

The case law of this circuit

demonstrates that some indication of the legal basis

for the state court's denial of relief on a federal

claim is generally necessary to support a conclusion

that the state court has made an implied fact-finding

as to a factual issue underlying the claim.

In Armstead v. Scott, 37 F.3d 202 (5th Cir.1994),

the habeas petitioner alleged that his defense

counsel was unconstitutionally ineffective because

he falsely promised the petitioner that his wife

would receive probation if he pled guilty. See id.

at 205. The state habeas court made no express

findings of fact on this issue and merely denied

relief. See id. at 208. This court held that the

state court had made no fact-finding--express or

implied--on this issue. See id. at 208-09.

Likewise, in Blackmon v. Scott,

22 F.3d 560 (5th Cir.1994), we concluded that a

habeas petitioner was entitled to an evidentiary

hearing on a number of his claims for habeas relief,

the viability of which hinged upon resolution of

fact issues, because the state habeas court had not

entered fact-findings disposing of the underlying

fact issues in denying the petitioner's state habeas

petition. See id. at 566-67. We therefore conclude

that neither the state district court nor the Court

of Criminal Appeals made any implicit findings of

fact on the issue of whether Goodwin requested to

have an attorney present during custodial

interrogation when first taken to the Burlington

police station.

Because the state courts made no

fact-finding on this issue, they did not provide

Goodwin with a full and fair hearing for its

resolution. Goodwin is therefore entitled to an

evidentiary hearing so that the district court may

determine whether Goodwin invoked his Fifth

Amendment right to counsel, thereby rendering his

confessions inadmissible at trial. "This should not

be a wide-ranging fishing expedition, but a brief

adversarial hearing concerning a discrete [factual

issue]." Perillo, 79 F.3d at 445.

C. Withholding Exculpatory

Evidence and Knowing Use of Perjured Testimony by

Prosecution

Goodwin advances two arguments

relating to the testimony of Delbert Burkett, a

witness at Goodwin's trial who was Goodwin's

cellmate in the Montgomery County Jail during the

early part of 1987. Burkett testified at the

sentencing stage of Goodwin's trial that Goodwin had

bragged to him about the murder of Tillerson and

that Goodwin showed no remorse at having committed

the murder. Goodwin alleges that the prosecution (1)

knowingly failed to correct Burkett's perjurious

testimony during sentencing that he did not testify

in exchange for a deal from the state lessening his

sentence on a state crime for which he had been

previously convicted and (2) failed to inform

Goodwin of the existence of a deal between Burkett

and the state that would have constituted material

impeachment evidence at trial. Goodwin contends that

a genuine issue of material fact exists as to each

of the above claims, and that he is therefore

entitled to an evidentiary hearing on them. We

conclude that no such genuine issues of material

fact exist and that Goodwin is not entitled to an

evidentiary hearing on these claims.

1. Knowing use of perjured

testimony

"A state denies a criminal

defendant due process when it knowingly uses

perjured testimony at trial or allows untrue

testimony to go uncorrected." Faulder v. Johnson, 81

F.3d 515, 519 (5th Cir.) (citing Napue v. Illinois,

360 U.S. 264, 79 S.Ct. 1173, 3 L.Ed.2d 1217 (1959)),

cert. denied, --- U.S. ----, 117 S.Ct. 487, 136 L.Ed.2d

380 (1996). To obtain a reversal based upon a

prosecutor's use of perjured testimony or failure to

correct such testimony, a habeas petitioner must

demonstrate that "1) the testimony was actually

false; 2) the state knew it was false; and 3) the

testimony was material." See id.; Blackmon v. Scott,

22 F.3d 560, 565 (1994). False evidence is

"material" only "if there is any reasonable

likelihood that [it] could have affected the jury's

verdict." Westley v. Johnson, 83 F.3d 714, 726 (5th

Cir.1996) (internal quotation marks omitted), cert.

denied, --- U.S. ----, 117 S.Ct. 773, 136 L.Ed.2d

718 (1997).

On April 16, 1987, Burkett was

sentenced to five years imprisonment for possession

of a controlled substance, having violated the

conditions of his previous sentence of deferred

adjudication on the offense. That same day, two

other criminal charges pending against Burkett were

dismissed. At trial, Burkett testified that he had

received no promises of consideration from the state

in exchange for his testimony at Goodwin's trial as

of the time of his sentencing on the charge of

possession of a controlled substance. Burkett also

testified that he had no idea that the state desired

to have him testify until he was bench-warranted

from state prison back to Montgomery County in July

1987 to discuss the Goodwin case with prosecutors.

Goodwin claims that a fact issue

exists as to the falsehood of both of these pieces

of testimony as well as the state's knowledge of the

falsehood. He therefore argues that the district

court erred in denying him an evidentiary hearing to

explore these claims. We disagree.

Goodwin has presented no

competent summary judgment evidence creating a fact

issue as to the falsehood of Burkett's testimony

that the state had not offered him any sort of deal

in exchange for his testimony as of the time of

Burkett's sentencing on his charge of possession of

a controlled substance. In support of his claim that

this testimony was false, Goodwin offers the

affidavit of Kathryn Jean Burkett, Burkett's ex-wife.

Her affidavit states that Burkett informed her

before he was transported from county jail to the

Texas Department of Corrections to serve his five

year sentence that "he was going to get at least one,

and maybe more of his charges dismissed in exchange

for his testimony."

Burkett's alleged statement to

his ex-wife only creates a fact issue as to whether

he entered a deal with the state prior to April 16,

and therefore as to whether his testimony to the

contrary at trial was false, if the statement is

true. To that extent, Burkett's alleged statement is

hearsay, as it is an out-of-court statement offered

to prove the truth of the matter asserted.

See FED.R.EVID. 801(c). Because Goodwin has not

demonstrated that Burkett's alleged statement to his

wife fits any exception to the general rule that

hearsay is inadmissible, see FED.R.EVID. 802, 803,

the statement is incompetent summary judgment

evidence. See Barhan v. Ry-Ron Inc., 121 F.3d 198,

202 (5th Cir.1997).

None of the other summary

judgment evidence presented to the district court,

including the affidavits of the prosecuting

attorneys and the numerous affidavits of Burkett,

contradict Burkett's trial testimony that the state

had offered him no deal in exchange for his

testimony as of the time that his sentence for

possession of a controlled substance was imposed.

Because Goodwin has failed to demonstrate the

existence of a fact issue as to the falsehood of

Burkett's testimony at trial, he is not entitled to

an evidentiary hearing on this issue.

2. Failure to disclose the

existence of a deal

"The prosecution's suppression of

evidence favorable to the accused violates the Due

Process Clause if the evidence is material either to

guilt or to punishment." Kopycinski v. Scott, 64

F.3d 223, 225 (5th Cir.1995) (citing Brady v.

Maryland, 373 U.S. 83, 87, 83 S.Ct. 1194, 1196, 10

L.Ed.2d 215 (1963)). This includes evidence that may

be used to impeach a witness's credibility. See id.

(citing United States v. Bagley, 473 U.S. 667, 676,

105 S.Ct. 3375, 3380, 87 L.Ed.2d 481 (1985)). "[E]vidence

is material only if there is a reasonable

probability that, had the evidence been disclosed to

the defense, the result of the proceeding would have

been different." Bagley, 473 U.S. at 682, 105 S.Ct.

at 3383; Kopycinski, 64 F.3d at 225-26. If the

prosecution withholds evidence that satisfies the

above definition of materiality, then harmless-error

analysis is inapposite and habeas relief is

warranted. See Kyles v. Whitley, 514 U.S. 419, 435,

115 S.Ct. 1555, 1566, 131 L.Ed.2d 490 (1995) ("[O]nce

a reviewing court applying Bagley has found

constitutional error there is no need for further

harmless-error review. Assuming, arguendo, that a

harmless-error enquiry were to apply, a Bagley error

could not be treated as harmless, since a reasonable

probability that, had the evidence been disclosed to

the defense, the result of the proceeding would have

been different necessarily entails the conclusion

that the suppression must have had substantial and

injurious effect or influence in determining the

jury's verdict." (internal quotation marks and

citations omitted)).

Goodwin alleges that a fact issue

exists as to whether the state entered into a deal

with Burkett pursuant to which Burkett would receive

favorable treatment in exchange for his testimony at

the sentencing phase of Goodwin's trial. He contends

that, if such a deal existed and the state failed to

reveal it to him, he is entitled to a new trial on

Brady grounds. Goodwin therefore argues that the

district court improperly denied him an evidentiary

hearing to resolve the factual dispute of whether a

deal existed between the state and Burkett. Because

Goodwin has offered no competent summary judgment

evidence establishing a fact issue as to whether the

state had entered a deal with Burkett whereby he

would receive favorable treatment in exchange for

his testimony, Goodwin is not entitled to an

evidentiary hearing on this claim.

In support of his Brady claim,

Goodwin offers one of the three affidavits executed

by Burkett and an affidavit of Kathryn Burkett.

Burkett's affidavit does not establish a fact issue

as to the existence of a deal that would satisfy

Brady 's requirement of materiality. In his

affidavit, Burkett states that prosecutors indicated

"that they would look into pending criminal matters,

which included a probation revocation in Travis

County and assistance with [his] parole for the

Montgomery County charges."

Specifically, Burkett claims that

one of the prosecutors "told [him] she could not

promise anything concerning the Travis County

probation, because it was from another county, but

she said she would look into it if she could."

Assuming that such a statement by the prosecutor

constitutes an agreement, it is immaterial because

the potential benefit to Burkett was so marginal

that "it is doubtful it would motivate a reluctant

witness, or that disclosure of the statement would

have had any effect on his credibility." McCleskey

v. Kemp, 753 F.2d 877, 884 (11th Cir.1985) (en banc)

(concluding that a detective's promise to "speak a

word" for a witness in exchange for his testimony

was not reasonably likely to have changed the

judgment of the jury had it been disclosed).

We therefore conclude that, even

if the prosecutor made the "agreement" that Burkett