No. 74,118

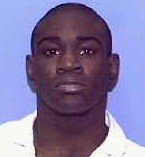

Jamaal Howard, Appellant,

v.

The State of Texas

October 13, 2004

Appeal

from Hardin County

Per Curiam. Meyers and Holcomb, JJ.,

dissent.

The

appellant, Jamaal Howard, was convicted in April 2001

of capital murder,

(1) an offense

that was committed on May 12, 2000. Pursuant to the jury's answers

to the special issues set forth in Code of Criminal Procedure

Article 37.071, Sections 2(b) and 2(e), the trial judge sentenced

the appellant to death.

(2) Direct appeal

to this Court is automatic.

(3) The appellant

raises nine points of error. We affirm.

In

his sixth point of error, the appellant claims that the evidence

is legally insufficient to support the jury's verdict on the issue

of his future dangerousness. He argues that there was no evidence

of premeditation to commit the instant murder and that he has no

history of prior criminal violence. Following is a review of the

relevant evidence in a light most favorable to the verdict.

See

Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307 (1991).

The

appellant stole a gun from his grandfather the night before the

murder and hid it. Despite his family's efforts to persuade him to

turn over the gun, the appellant refused. The following morning,

the appellant retrieved the gun and walked several blocks from his

house to the Chevron store. After peering in the windows, he

entered the store, went into the secured office area where the

victim was sitting, cocked the gun, and shot the victim in the

chest. The appellant stole $114.00 from the cash register and

reached over the dying victim to steal a carton of cigarettes

before leaving. The offense was recorded on videotape. The

appellant denied committing the offense until he was told it was

videotaped. He told the officer who took his statement that he was

not sorry for committing the offense.

At

the punishment stage of trial, the State presented evidence that

the appellant demonstrated a disregard for authority and school

rules despite the continued efforts of his mother and educators.

During one incident, the appellant punched a pregnant teacher in

the chest with his fist when she asked him to return to his seat.

When the appellant was assigned to an alternative school, he

refused to comply with its rules and standards, and he was defiant

and disruptive. The State also presented evidence of the

appellant's possession of controlled substances, his fighting with

police officers and resisting arrest, his committing of several

burglaries as a juvenile, and his fighting with other inmates. Dr.

Edward Gripon testified for the State that the appellant was not

suffering from schizophrenia, but rather was suffering from

antisocial personality disorder.

The

evidence is sufficient to support the jury's verdict. The

appellant's actions in committing the crime were senseless and

deliberate; his actions immediately following its commission were

equally so. Given these actions, combined with his appellant's

past history of assaultive conduct, disregard for authority and

rules, drug offenses, and juvenile offenses, and the expert

testimony that the appellant displayed an antisocial personality

disorder, the jury rationally could have concluded beyond a

reasonable doubt that the appellant would probably commit criminal

acts of violence that would pose a continuing threat to society.

Point of error six is overruled.

In

his seventh point of error, the appellant claims that the evidence

is insufficient to support the jury's verdict on the mitigation

special issue. The appellant

argues that this Court's refusal to review the jury's verdict

denies him the right to a "meaningful appellate review." This

Court has repeatedly declined to review the sufficiency of the

mitigating evidence and has rejected the claim that it deprives a

defendant of a meaningful appellate review.

Salazar v. State, 38 S.W.3d 141, 146 (Tex. Cr.

App.),

cert. denied, 534 U.S. 855 (2001);

McGinn v. State, 961 S.W.2d 161, 166 (Tex. Cr.

App.1998),

cert. denied, 525 U.S. 967 (1998). Point of error seven is

overruled.

In

his first point of error, the appellant claims that the trial

court erred in overruling his objection to the prosecutor's jury

argument at punishment. During the punishment stage, the

prosecutor argued:

When

he is not waiting for capital murder trial and not going to have

to be on his best behavior, then what is he going to act like?

Gang activity, 5-9 Hoover Crypts [sic],

and Crypts [sic]

are in prison, too. He will fall right in with his old buds;

extortion, rape, drug trafficking --

The

appellant's objection to the argument as outside the record was

overruled.

Previously, however, during the prosecutor's argument at the

punishment stage, the prosecutor made similar statements without

objection. For instance, the prosecutor opened his argument, with

no objection, as follows:

[U]ntil

Dr. Laine's medical record came in through Dr. Fason and -- I

didn't know that the defendant had been stalking a girl and I

didn't know that he had told Dr. Laine that

he admitted to being a gang member, smoking marijuana,

drinking alcohol, carrying a gun.

(Emphasis

added). The prosecutor further argued, without objection, that the

appellant would have the opportunity to join prison gangs and

participate in their activities, if he chose to:

The

gentleman from the prison prosecution unit told you also that

drugs are a big factor with prison gangs, that they sell drugs to

make money in prison gangs. So, this will be another indication

that [the appellant] would have the opportunity, if he wants to,

if he hadn't learned his lesson, that he is going to be a future

danger.

In

light of the jury's previous exposure to these similar arguments,

suggesting the potential for the appellant's participation in gang-related

activities in prison, any error is harmless.

Cf. Massey v. State, 933

S.W.2d 141, 149 (Tex. Cr. App. 1996) (holding that if defendant

objects to admission of evidence but same evidence is subsequently

introduced from another source without objection defendant waives

earlier objection).

Point of error one is overruled.

In

his third point of error, the appellant claims that the trial

court erred in overruling his objection to the prosecutor's jury

argument at the punishment stage of trial. During closing argument,

the prosecutor made the following comments:

[Prosecutor]:

That's the type of person you're dealing with in Jamaal Howard.

And since that time not one feeling of remorse, not one word of

sorry.

[Defense

objection, overruled]

[Prosecutor]:

In fact, he told Ranger Wilson, "I'm not sorry." That's the type

of person you are dealing with in Jamaal Howard.

Appellant claims the prosecutor's argument was a comment on his

failure to testify, in violation of the Fifth Amendment to the

United States Constitution, and could not be understood as based

on his

discussion with Ranger Wilson.

Texas

Ranger L.C. Wilson took the appellant's written statement.

Following is an excerpt from Wilson's testimony:

[Prosecutor]:

Did [appellant] give any reason why he did it?

[Wilson]: No. No, he never did.

Q.

Did he express any remorse to you?

A.

No, he didn't, you know, because right at the end of that

statement I asked him, I said, "Jamaal, you know, in a year or so

from now a jury is going to hear this and they are going to want

to know why you did it. You know, now is your chance, you know.

I'm asking you to explain to anybody." He didn't have a reason. I

asked him, you know, "Do you have any remorse for this?" He said,

"No." And I said, "You're willing to sign that statement? You have

no remorse?" And he did.

On

cross-examination, defense counsel asked Wilson if he had asked

the appellant if he understood the meaning of the word "remorse."

Wilson responded that he did not specifically remember asking the

appellant if he understood the meaning of the word remorse,

but he remembered asking him,

"Do you feel sorry about what you did?"

This

Court has held that a prosecutor's comment on a defendant's

failure to show remorse is tantamount to a comment on his failure

to testify.

Davis v. State, 782 S.W.2d 211, 222 (Tex. Cr.

App. 1989)(citing

Dickinson v. State, 685 S.W.2d 320, 324 (Tex. Cr.

App.1984)),

cert. denied, 495 U.S. 940 (1990). However, if there is

evidence in the record supporting the comment, then no error is

shown.

(4)

Id. (citing

Fearance v. State, 771 S.W.2d 486, 514 (Tex. Cr.

App. 1988)). Here, Wilson testified that the appellant told him he

had no remorse. The prosecutor's argument was therefore a proper

summation of the evidence.

See id. Point of error three is overruled.

In

his second point of error, the appellant claims that "[a]

procedure that permits the death penalty to be inflicted on

defendants with mental retardation despite their diminished

personal culpability violates the Eighth Amendment to the United

States Constitution." The appellant argues that the Eighth

Amendment requires that mentally retarded individuals, like

himself, be excluded as a class from execution. As evidence of his

mental retardation, he points to the testimony of Dr. James Duncan,

who testified that the appellant had borderline to mildly impaired

intellectual functioning. The appellant

argues that an individual put to death must be able to rationally

appreciate and evaluate the consequences of his actions. In a

Supplemental List of Authorities, the appellant cites to

Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002).

In

Atkins, the United States Supreme Court concluded that the

execution of a mentally retarded individual is unconstitutionally

excessive under the Eighth Amendment.

Id., at 321. Recognizing that "not all people who claim to be

mentally retarded will be so impaired as to fall within the range

of mentally retarded offenders about whom there is a national

consensus," the Court left to the States "the task of developing

appropriate ways to enforce the constitutional restriction upon

its execution of sentences."

Id., at 317.

As a

stop-gap measure for cases that we must decide in the absence of

legislation, this Court has set temporary guidelines for

determining mental retardation in the death penalty context.

Ex parte Briseno, 135 S.W.3d 1, 5 (Tex. Cr. App. 2004). We

apply the definition found in the "Persons with Mental Retardation

Act" (Health & Safety Code, Chapter 591): "'Mental retardation'

means significantly subaverage general intellectual functioning

that is concurrent with deficits in adaptive behavior and

originates during the developmental period."

(5) This

definition is essentially the same as the one utilized by the

American Association of Mental Retardation (AAMR).

(6) "Significantly

subaverage general intellectual functioning" is defined as an IQ

of 70 or below.

(7) "'Adaptive

behavior' means the effectiveness with or degree to which a person

meets the standards of personal independence and social

responsibility expected of the person's age and cultural group."

(8) The

developmental period is understood to be the period before age 18.

(9)

In

this case, there was little testimony bearing on the issue of the

appellant's limitations in adaptive behavior, other than the

testimony about his lack of personal hygiene which was presented

by the defense as indicative of the appellant's alleged

schizophrenia. Although there was testimony that the appellant was

unwilling to meet the rules imposed by the alternative school,

this testimony was presented as bearing on the issue of whether

the appellant was suffering from a mental illness, or whether his

actions were, as the State contended, volitional.

Dr.

Fred Fason, a defense expert, testified that when he first met

with the appellant and began to administer one of the

psychological tests, the appellant did not know some of the words

in the first few questions. Fason testified that this caused him

to conclude that the appellant could not read at the sixth grade

level and to question whether the appellant was mentally retarded.

However, upon questioning defense counsel, talking to the

appellant's mother, and retrieving the appellant's school records,

Fason discovered that the appellant had started out in school as a

very bright student; the appellant was in the ninetieth percentile

in math in the second grade, but had dropped to about the

thirtieth percentile in the fifth grade. Fason theorized that the

appellant's declining performance in school was due to the onset

of schizophrenia.

One

of the court's independent experts, Dr. Duncan, reached a similar

conclusion. At one of the appellant's competency hearings, Duncan

testified that he gave the appellant portions of an I.Q. test and

that the appellant tested in the borderline to mildly impaired

range which Duncan said was the level of an eleven or twelve year-old.

On cross-examination, however, it was emphasized that Duncan had

given the appellant only

portions of an I.Q. test on which he had based an

estimate of the appellant's I.Q. The State's expert, Dr.

Gripon, testified that the appellant's problems in school stemmed

solely from his attention-deficit disorder which was addressed

when he took his medication; when the appellant refused to take

his medication, his grades declined and his behavior deteriorated.

Gripon did not see any evidence that the appellant suffered from

schizophrenia.

Although experts for both the State and the defense testified that

the appellant's intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior

were impaired to some degree, the testimony was not sufficiently

developed to establish that appellant was "mentally retarded"

under the guidelines we set in

Briseno. Because the evidence does not support the

appellant's claim that he is mentally retarded, we reject his

Eighth Amendment claim.

See Stevenson v. State, 73 S.W.3d 914, 917 (Tex. Cr. App.

2002). Point of error two is overruled.

In

his fourth and fifth points of error, the appellant claims that he

was denied effective assistance of counsel as guaranteed by the

Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution and Article I,

Section 10 of the Texas Constitution, respectively, when his trial

counsel failed to introduce expert-witness testimony that he had

an I.Q. in the range of 65 to 70.

The

appellant claims that, during the hearing on his competency to

stand trial, Dr. Duncan testified that he had assessed the

appellant's I.Q. in the range of 65 to 70. At the guilt phase of

trial, however, although Duncan testified about the appellant's "borderline

to mildly impaired functioning," he neither testified specifically

to his determination of the appellant's I.Q., nor was he

questioned by the appellant's counsel about the I.Q. test he had

administered. The appellant claims that his counsel was

ineffective in failing to elicit Duncan's testimony about his I.Q.

at the guilt or innocence phase.

To

establish ineffective assistance of counsel, the appellant must

meet the two-pronged test set forth in

Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668 (1984);

Ex parte Varelas, 45 S.W.3d 627 (Tex. Cr. App. 2001). First,

the appellant must demonstrate that counsel's performance was

deficient.

Id., at 629.

Second, the appellant must show that counsel's performance

prejudiced his defense at trial.

Id. That is, he must show that there is a reasonable

probability that the result of the proceeding would have been

different but for the errors made by counsel.

Id. Allegations of ineffectiveness must be firmly founded in

the record as counsel is presumed to have rendered adequate

assistance and made all significant decision in the exercise of

reasonable professional judgment.

Id.

The

record from the competency hearing reflects that Duncan testified

that he administered to the appellant only "some portions" of an

I.Q. test in order to arrive at an "estimate" of the appellant's

I.Q.:

[Duncan]:

I gave [the appellant] some portions of an I.Q. test to arrive at

that estimate, some of the verbal subtests of the Weschler [A]dult

[I]ntelligence [S]cale.

* * *

Q.

Okay. And, so, were you able to arrive at a numerical I.Q. score?

A. I

would say in the range of 70; but because I didn't give the full

test, that number would be -- there would a range there. I would

say that based on the -- scoring the subtest that I gave and

figuring out that number, would be a 65 to 70 kind of I.Q. range.

Given

that Duncan administered only "portions" of an I.Q. test to arrive

at an "estimate" of the appellant's I.Q., we presume that the

appellant's defense counsel was exercising reasonable trial

strategy by not eliciting such testimony from Duncan before the

jury, in light of the speculative weight of the testimony and its

susceptibility to cross-examination.

(10) Moreover,

the appellant has not shown that the outcome of the trial would

have been different had the testimony been elicited. Points of

error four and five are overruled.

In his eighth and

ninth points of error, the appellant claims that his trial counsel

was ineffective under the Sixth Amendment and Article I, Section

10 of the Texas Constitution, respectively, by failing to object

to the prosecutor's argument that appellant had been "stalking"

someone when he claims no such evidence was introduced at trial.

During the punishment stage of trial, the prosecutor argued that

the appellant "had been stalking a girl": "Then we find out that

he was stalking a young lady. That's a threat of violence."

During the State's

cross-examination of defense witness Dr. Fred Fason, the

prosecutor questioned Fason about the factors he considered in

making his diagnosis of the appellant:

[Prosecutor]: And

subsequent to that, as an adult, having charges related to

delivery of cocaine, possession of cocaine, would that be

important in making that diagnosis?

[Fason]: Well, it's

something you take into consideration; but it wouldn't be -- it's

not pathognomonic of -- of any social personality disorder.

Q. And even the

history that his mother gave you that he was stalking some young

lady --

A. Yes.

Q. -- would that be

important in diagnosing antisocial personality?

A. Not in the way

it was presented, no. I mean it's significant. It's another

-- it's much like -- arriving at a diagnosis, in a way, is kind of

like working a jigsaw puzzle. You take a whole bunch of different

pieces and you see how they fit together to come out with a

picture; and that would be a piece of the puzzle.

Q. And taking that all

together, you know, a history from the age of 13, from theft, to

15, 16, dealing drugs, to stalking, to capital murder,

all that taken together doesn't that kind of suggest that there

may be an antisocial personality here?

(Emphasis added).

Fason did not refute the suggestion that the appellant had

reportedly stalked a girl. Rather, Fason affirmed the prosecutor's

suggestion. Fason's affirmative response to the prosecutor's

question made the suggestion become evidence, albeit slight. Thus,

the prosecutor's argument referring to the evidence was not

objectionable. Points of error eight and nine are overruled.

The judgment of the

trial court is affirmed.

En banc.

Delivered October 13,

2004.

Publish.

1.

See Tex. Penal Code § 19.03(a).

2. Tex. Code Crim. Proc.

art. 37.071, § 2(g).

3. Art. 37.071, § 2(h).

4. The appellant did not

complain at trial, nor does he complain in this appeal, about the

admission of Wilson's testimony concerning the appellant's

statements regarding his lack of remorse.

5.

Id., § 591.003(13) (quoted in

Briseno, 135 S.W.3d, at 8).

6.

See Briseno, 135 S.W.3d ,at 7.

7.

Id., at 7, n.24.

8.

Id., at 7, n.25 (quoting § 591.003(1)).

9.

Id., at 7 (discussing AAMR definition).

10.

Atkins v.

Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002), discussed in connection with

point of error two above, was decided on June 20, 2002. Appellant

was tried and convicted in April 2001.