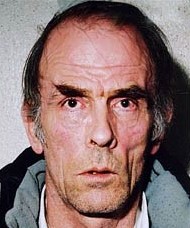

Howard, now

61, is serving a life sentence in Frankland Prison, Durham,

for raping and murdering 14-year-old Hannah Williams in Kent

in 2001. He is the only suspect for the murder of 15-year-old

Arlene Arkinson in 1994, and in recent months he has been

questioned about the rapes and murders of several other

women and girls in Ireland and England. He is known to have

attempted to rape a six-year-old child in 1965, when he was

21, a young woman in 1969, and an older woman in 1973.

Gahan, now 28, is angry. Howard got away

with what he did to her. Hannah Williams' mother is angry.

She believes Howard should have been in jail at the time he

preyed on her daughter. The Arkinson family is angry,

believing he could and should have been convicted of

murdering Arlene, whose body has never been found. "We need

a full public inquiry into how this man got let go again and

again to do the things he did," says Arlene's sister,

Kathleen.

The case of Robert Howard suggests that

the authorities - from the police to the prosecutors to the

judiciary - simply haven't taken rape seriously enough.

Howard got nine days in borstal for the assault on the six-year-old.

He got six years for attempted rape of the young woman, and

was free within three. After he raped the older woman, a

psychiatrist warned that Howard was a dangerous psychopath

and should be jailed for as long as possible. He got 10

years and was out in seven.

In 1994, after Howard raped Gahan,

another psychiatrist warned that he was dangerous to women

and becoming more so. He got a suspended sentence. Howard

moved easily between the Republic of Ireland and the north,

and across the Irish Sea to England and Scotland. He was

rarely monitored, and never for long. Liaison between police

forces was minimal.

Gahan, who has moved back to the Irish

midlands where she was born, is still deeply traumatised by

the violence Howard inflicted on her. She left home as a 15-year-old

emerging from a troubled childhood. Her mother had been

killed in an accident when she was five. "My father was

finding it hard to control us," she says. "There were 10 of

us. My friend had moved up to the north and I decided to

follow. I was running away from Daddy, really, but it wasn't

his fault. I was wild."

Her friend's boyfriend knew a middle-aged

woman called Pat Quinn, who said Gahan could stay in her

house in Castlederg, where she lived with her own teenage

daughter, Donna. Castlederg is one of those small Northern

Irish towns that is well described by Yeats's phrase, "Great

hatred, little room." It was deeply afflicted by the

Troubles.

Gahan liked it. She got a job washing

dishes in a Chinese restaurant. She became part of a circle

of teenagers, including Donna and Arlene Arkinson. Their

social life revolved around nights in bars and discos in

Castlederg and neighbouring towns in Tyrone, and in Donegal

in the Republic, reached by a network of narrow, mountainous

roads through woods and bogs. The border meanders crazily

across this lonely territory. Robert Howard, then nearly 50,

was Pat Quinn's boyfriend, though he was more interested in

the teenage girls he met through Donna. He let them stay at

his flat on Main Street.

"He knew I had nothing," says Gahan. "He

knew everything about me. He bought me cigarettes and

runners and things. He used to bring us up to the bog to cut

turf. He brought me out for drinks. I knew him as Bob. He

called me Mick. He was so nice to me. He was from the south,

like me. I'd left Daddy, and he was like a daddy who let me

do what I wanted. I thought the world of him."

A few months after Gahan had arrived in

Castlederg, Howard suggested an elaborate plan to her.

Ostensibly, he was fixing her up with a young taxi driver

she fancied. She was to tell everyone she was going away for

the weekend, get a bus to the next town, and then come back

secretly to meet Howard - and the taxi driver - at his flat.

Except the taxi driver never came.

Howard took Gahan to a pub in the village

of Sion Mills that night, but left when they saw someone

they knew. "I was afraid," says Gahan, "but I don't remember

why. When we got to the flat, I had a pounding headache. He

gave me some pills. I remember sitting on his knee. I

remember nothing then until I woke up the next morning naked

in his bed. He started coming on to me, and I said no. He

said I hadn't said that last night. He started getting

annoyed then, and that is when he put the rope round my neck."

When she escaped, after three days held

captive, Gahan told police she'd been raped, but she felt

they didn't believe her. "They banged the table and shouted

at me," she says. They wanted to know why she hadn't tried

to get away sooner, and why she did not, initially, tell

them about her interest in the taxi driver. Looking back,

she can see the control Howard had over her. "It was the way

he had me thinking," she says. There was compelling evidence

to back her account of what had happened: strangulation

marks on her neck; her fingerprints on the windowsill from

which she had jumped; a rope.

Gahan was taken to a children's home and

soon afterwards returned to her family, then to a job in

England. Howard was arrested and released on bail. He was

ordered to stay with the Quinns, even though this was a

household that included the teenage Donna. He was instructed

not to go out at night, or into pubs. In the summer of 1994,

Gahan was informed by the police in Northern Ireland that

her case was coming up. She returned to Ireland, but was not,

in fact, called to give evidence. Howard had originally been

charged with five rapes and with buggery. But the charges

were dropped.

Instead, Howard agreed to plead guilty to

unlawful carnal knowledge. The implication was that Gahan

had been a willing partner and that the offence lay only in

the fact that she was, at 16, under the legal age of consent

(17 in Northern Ireland). Her statements had been heavily

edited. A prosecuting lawyer told the court that no rope had

been found. Judge David Smyth ordered that a psychiatric

report be prepared on Howard, and said that if it was

satisfactory, he would not be sent to jail. He was released

again on bail. This was extraordinary - by that stage,

Howard was suspected of having murdered 15-year-old Arlene

Arkinson.

On August 13 1994, Arlene was babysitting

at her sister Kathleen's home on a housing estate in

Castlederg. Kathleen returned home at about 11pm, and soon

afterwards Donna Quinn arrived to pick up Arlene. "She said

it was her and her boyfriend and her mother and Bob Howard

that were going out," says Kathleen. They were going to a

disco at the Palace Hotel in Bundoran. An old-fashioned

resort full of boarding houses and bars and amusement

arcades, Bundoran is perched on the chilly edge of the

Atlantic in Donegal. Donna said they'd be back by two the

following morning. Kathleen said good night to her youngest

sister. She never saw her again.

"Arlene was wild, like me," Gahan recalls.

"We were alike, too, because I had no one telling me what to

do and nor had she. We got on great."

Arlene's mother had died when she was 11.

She lived between the homes of her older brothers and

sisters, though she sometimes returned to her father's house.

"I used to hear her upstairs, crying, 'I want my mummy,' "

he remembers, as he sits in his living room, looking at

photographs of his lovely, laughing daughter, missing now

for more than a decade.

At first, after Arlene disappeared, the

Quinns covered up for Howard, claiming Arlene hadn't gone to

Bundoran. However, it quickly emerged that after the night

out in Bundoran, Howard had dropped off the others before

driving away with Arlene. He claimed that he had dropped her

off in Castlederg, and that he'd seen her in a car in the

town the next day. He was not believed. Pat Quinn admitted

Howard had got back home much later than she had originally

said. The terms of his bail on the charges concerning Gahan

included a curfew, which he'd broken, but still he was not

held in custody.

A petrol bomb was thrown into the Quinns'

house. Howard was driven out of Castlederg by members of

Arlene's family. He sold the car he'd used the night Arlene

disappeared. For a time, he lived rough in a van across the

border. Again, he was moved on by local men who knew his

reputation. It was a full six weeks after Arlene disappeared

before he was arrested. One of Arlene's sisters recalls

something a local RUC officer said at this time: "He said,

'I wish I could show you that man's file. You wouldn't

believe it.' " Still, at the time he was neither charged nor

brought to trial.

As an adult, Robert Howard called himself

the Wolfman and the Wolfhill Werewolf. He gave himself a new

middle name, Lesarian, believed to be a reference to a

mythical child killer. He was born in Wolfhill, County Laois,

in the south-east of Ireland, in 1944. He was a tall, gangly

boy, bright enough at school, according to some of those who

knew him then, but edgy, easily distracted. "He mitched [played

truant] a lot," says one contemporary. "His father worked in

the local brick factory and drank heavily in the local pub.

His mother had nine children to raise. There would have been

very little money brought home."

By the time he was 13, Robert was in

trouble. Convicted of burglary, he was sent to St Joseph's

Industrial School, in Clonmel, not far from his home area, a

reformatory run by priests and brothers. The truth about how

such Irish Catholic institutions were run has begun to

emerge in recent years. "These people were monsters," says

one former inmate. "The place was unbelievable. We were

starved. We were beaten with leather straps with coins sewn

into them until we were bleeding. We had to gather turnips

and stones for the local farmers. You had no name. You had a

number. There were boys in there going around like zombies.

We were terrified, all the time - a lot of us were damaged

for life. Love was never spoken of, never shown. There was

never a comforting word. Just relentless violence." There

was also sexual abuse, and Howard would later claim to have

been a victim of this.

On his release, his father threw him out

of the family home. The 16-year-old lived rough in barns and

outhouses, and possibly in old shafts and tunnels from the

days when Wolfhill had coalmines. One man, a child in the

1950s, recalls making a disturbing discovery in his father's

hayshed. "We found old cans and blankets and things - Howard

must have been sleeping there. We also found a diary. It was

all about how he wanted to break into women's houses when

they were in the bath, and the violent things he'd do to

them. My father caught us reading it and took it away."

Another local man recalls being told by a

neighbour that, while out hunting one day, he had come upon

a local farmer performing a sexual act on the teenage Howard

in the woods. The man didn't intervene, but fired a shot

into the air.

Howard continued to steal. He'd rob from

local shops and take cars. He was sent to a second reform

school, St Conleth's, in Daingean, County Offaly, another of

the most notorious of Ireland's brutal institutions for

young offenders. A former priest who worked there said the

priests were "programmed with an extraordinary level of

violence" and that "most of the boys ended up totally

disturbed".

Howard moved to England. In 1965, when he

was 21, he broke into a house in London and ordered a six-year-old

girl to undress, claiming he was a doctor. He attempted to

rape the child, and hurt her. A week later he returned and

tried to break in again. This time he was caught. His

punishment was nine days in a borstal, after which he was

sent back to Ireland. At that time it was common for Irish

criminals to be sent home in this way, a system of informal

deportation. He didn't stay.

In 1969, Howard broke into the home of a

young married woman in Durham and attempted to rape her. She

ran, naked and screaming, from the house. He grabbed her by

the throat before neighbours managed to drag him away. He

was sentenced to six years in jail, and served three, in

Frankland Prison. During his time there, he assaulted a

female member of staff. By 1973, he was free, and was again

sent back to Ireland. Using the name Lesley Cahill, he got a

factory job in the then prospering seaside town of Youghal,

County Cork.

One night in May that year, a 58-year-old

woman who lived alone woke up to find Howard in her bedroom.

He had broken into her house, which was beside his lodgings.

He made her hand over her money and keys, then forced her

upstairs again, breaking her ankle in the process. He tied

her to her bed, stuffed her mouth with cotton wool and raped

her, before driving off in her car. "She was a very

vulnerable person," says Willie Doyle, then the local Garda

sergeant. "She might have suffocated, but luckily for her

some relations called the next morning and found her. She

was very traumatised."

Howard was arrested at Dublin airport.

"He was very soft-spoken," recalls Doyle. "You would never

imagine he could be violent." Psychiatrist Dr David Dunne,

who interviewed Howard at the time, says he, too, was

surprised by Howard's "extremely courteous" demeanour. "He

was a very refined man, but I had seen his record and knew

he was also extremely dangerous. I sensed and feared he had

already killed someone. I knew his violence was likely to

get far worse, especially towards women. I believed him to

be an explosive psychopath. I wanted him to be sent to jail

for an indefinite period."

Howard could have got life. Instead, he

got 10 years. He was out again in 1981. An internal Garda

bulletin noted that he had returned to Wolfhill and "local

opinion is that he is not going to waste any time before

returning to his old tricks".

A woman who remembers him from this time

had her own horrific experience of sexual brutality. She was

the teenager who would become known a decade later as "the

Kilkenny incest victim". In 1981, aged 15, she was pregnant

with her father's child. He was beating and raping her

routinely, and used to take pornographic pictures of her

which he'd show to other men in local pubs.

"Bob used to come to our house sometimes

at night, and he and my father would drink whiskey and

poitín together," she says. "My father would say to him, 'Where

have you been?' He'd say, 'I've been visiting relations.' My

father would laugh. I always felt it was some sort of code.

He was creepy. They were birds of a feather." Her father was

eventually jailed for seven years.

In 1983, Howard got married to a young

woman he met in a Dublin hospital. The marriage lasted three

years. They lived at various addresses in Dublin. She, too,

was described as vulnerable, with emotional troubles; her

friends revealed recently that Howard was violent and cruel

to her. In 1988, he was jailed for 15 months for larceny. He

went to Northern Ireland in 1990 to attend an alcohol

treatment unit run by nuns in Newry, County Down. It was at

around this time that he met Pat Quinn and moved to

Castlederg.

He lived at first in a caravan park on

the edge of the town, a down-at-heel place where many of

those awaiting public housing lived. Not long after his

arrival there, in 1991, a young woman came from Dublin to

stay with him. He was 47, she was 22. He tied her up and

raped her repeatedly, was extremely violent and kept her as

a prisoner until, three weeks later, her parents arrived and

took her home.

The woman became pregnant as a result of

the rape and now has a 14-year-old child. The details of

what happened to her did not emerge until her family told

gardaí six years later, in 1997. Police decided she was too

vulnerable to give evidence and Howard was not charged. His

next known victim was Gahan.

"He has a strong desire to dominate

teenage girls both sexually and physically," wrote Dr Ian

Bownes, the forensic psychiatrist asked in September 1994 to

provide an assessment of Howard to assist Judge Smyth in

sentencing him for the "unlawful carnal knowledge" of Gahan.

"He has the propensity not only to commit further offences

of a similar nature ... but also to escalate his offending

behaviour." His activities were premeditated, involving the

identification and targeting of "a vulnerable victim" and

the use of a "sophisticated grooming process". Bownes said

he was pessimistic about Howard's ability to undergo any

treatment programme - his pattern of behaviour had been

established over many years and would be "extremely

resistant to change".

When Howard appeared in court again for

sentencing in January 1995, despite the damning psychiatric

report, Judge Smyth gave him a three-year suspended sentence.

As he freed Howard, the judge told him to stay away from

teenage girls. Bownes heard the news on the radio. "I was

somewhat surprised by the leniency of the sentence," he says.

"In retrospect, we can see the system failed disastrously."

Bownes never saw Dr Dunne's 1973 report on Howard. He was

not told that Gahan had alleged Howard used a noose.

What Howard would later refer to as "dark

days in Castlederg" were over. In March 1995, he moved to

Scotland, where he told local housing authorities that he

had left Northern Ireland "in a hurry". He said the IRA was

after him.

He was given a flat in the rough Glasgow

suburb of Drumchapel, near two schools. Pat Quinn came over

from Castlederg to join him. The Northern Ireland police

informed Strathclyde police about Howard's criminal record -

and that he was the chief suspect for the murder of Arlene

Arkinson.

Howard returned to Ireland several times,

but kept his Scottish base. Pat Quinn left in October, by

which time Howard already had another girlfriend, a woman

he'd met in a pub. She had a 10-year-old daughter. Then the

Sunday Mail, presumably acting on information obtained from

the police, outed Howard. The newspaper printed a photograph

of the "Face Of Evil" over a piece about the "twisted child

sex fiend" that detailed his criminal record and described

him as "one of Ireland's most dangerous sex offenders". The

sub-headline had a simple message: "Kick him out!"

Within hours, a crowd had descended on

the tenement house and the windows of Howard's second-floor

flat were smashed. He used a rope to escape from a back

window.

Howard was on the move again. A police

surveillance team located him at a hostel in Hither Green,

south-east London, but he was hounded out by other residents

who found out about his past. He disappeared for a time, and

was later traced to Brockley, then to Catford. A child

protection officer noted at the time that Howard was a

difficult subject to monitor.

By 1999, he was living with a woman

called Mary Scollom at her house in Northfleet, Kent.

Scollom had formerly been involved with the father of Hannah

Williams and had remained friendly with the girl after the

relationship ended. Scollom would take her for walks with

her dogs around the Blue Lake at the back of her house.

Hannah Williams' parents had separated

before she was born. When she was four, she had been

sexually abused by a boyfriend of her mother's and had spent

some time in care. In 2001, she was 14 and living with her

mother in the outer London suburb of Deptford. She had

learning difficulties and was described as immature.

Howard met Hannah through Scollom and

showed a great interest in her. In February 2001, he took a

home video of her, cuddling the dogs at the house he and

Scollom shared. On April 21, she left home to go shopping in

Deptford market, around the corner from her home in Elgar

Close. She had very little money, but she liked looking at

clothes. Her brother, Kevin, who had a Saturday job in the

market, heard her answering her mobile and having a very

brief conversation. She told the caller, "I'm going now."

By 10pm that night, Hannah's mother,

Bernadette Williams, was worried. Hannah had been supposed

to meet a friend that evening but hadn't shown up. She

wasn't answering her mobile. By 5am, Bernadette was frantic.

She went to the police. She felt she wasn't taken seriously

- several officers have since been disciplined for their

role in the initial stages of the investigation. Bernadette

made her own "Missing" posters and took them round local

shops and bars. But Hannah was gone.

Almost a year later, a workman was using

a digger to clear dense undergrowth on land near the Blue

Lake at Northfleet as part of the Channel Tunnel development.

He found a badly decomposed body wrapped in a blue tarpaulin.

Police initially thought it might be another missing girl,

but when they released a description of the clothes,

Bernadette knew it was her only daughter. "I finally found

out my daughter was dead, and that her body had been found,

by watching it on the telly," she says. "To find out that

way was unforgivable. I screamed and then I cried and cried."

Hannah's coffin was placed in a carriage

drawn by white horses. "She would have made a beautiful

bride," says her mother. "But instead of a white wedding, we

had a white funeral."

Hannah had been raped and strangled. The

blue rope that had been used to kill her was still wrapped

around her neck. Howard was arrested in March 2002 and

charged with her murder. During his trial, at Maidstone,

Kent, in October 2003, it was revealed that he had used his

girlfriend's mobile to call Hannah to her death.

Detective Inspector Colin Murray (now

retired), who led the investigation, had no witnesses and no

DNA evidence. However, he had circumstantial evidence and he

was also able to rely on "similar fact" evidence. A

traumatised young woman gave evidence that Howard had

brought her to the same place where Hannah Williams' body

was later found, and that he had tried to sexually assault

her. She had escaped.

Gahan came over from Ireland to give

evidence that showed Howard's grooming techniques.

Crucially, she also described how, when he was raping her,

Howard had put a noose around her neck. Kathleen Arkinson

gave evidence about Howard's part in Arlene's disappearance.

It took the jury just three hours to convict him. Sentencing

him to life imprisonment, Mr Justice McKinnon said, "It is

clear that you are a danger to teenage girls and other

women, and have been for a long time."

Reporting on the trial was severely

restricted because Howard had, by this time, also been

charged with murdering Arlene. "Mrs Williams hugged us at

the end of Hannah's trial and said, 'See you in Ireland,'"

says Kathleen Arkinson. "We assumed that she would be called,

and the others, too." But the public prosecution service in

Northern Ireland did not attempt to introduce similar fact

evidence. It has not explained this decision.

The jury that heard the case in Belfast's

crown court in the summer of 2005 knew nothing of the

patterns of behaviour Howard had established in a career of

sexual violence that spanned four decades. He was acquitted.

Weeks later, he was also acquitted of other charges of

sexual abuse against a 17-year-old girl in the 1990s.

Police from Northern Ireland, the

Republic and England have already held a one-day conference

to discuss other crimes with which Howard might be connected.

The police ombudsman for Northern Ireland, Nuala O'Loan, has

launched an inquiry into the handling of complaints against

Howard there. Gardaí in the Republic have applied for

permission to question Howard in connection with the

disappearances of at least two young women in the 1980s and

1990s. British police questioned him earlier this year about

13-year-old Amanda "Milly" Dowler, abducted and murdered in

2002.

Barry Cummins, a journalist who has

written a book about missing Irish women and children, says

a thorough investigation into Howard's life is now needed. "This

was a man who travelled freely all over Ireland and the UK,

and lived in many places," he says. "The police should be

looking at all unsolved disappearances, murders and sex

crimes against women and girls during the periods when he

was at large. They should be asking, 'Where was Howard?' "

Ireland established a sex offenders'

register only in 2001, and liaison on the monitoring of sex

offenders between the authorities in the North and the South,

and between Ireland and the UK, is seriously underdeveloped.

Howard was a skilled hunter. He carried

out random attacks on some of his victims, while others were

groomed. He could live rough, but also knew how to play the

system to get accommodation. He favoured poor areas. It was

easy to win women with low expectations. He tracked down

socially marginalised women to use as cover while providing

access to vulnerable young girls. The ones he chose had

typically already had bad experiences with men, and were

relatively unprotected. He faked kindness, and deceived many.

In the desolate boglands around

Castlederg, the search for Arlene Arkinson's body continues.