Appeal from the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Texas.

Before GARWOOD, HIGGINBOTHAM and

DAVIS, Circuit Judges.

GARWOOD, Circuit Judge:

Petitioner-appellant Jerry Lee

Hogue (Hogue) appeals the district court's denial of

his petition for habeas corpus under 28 U.S.C. 2254

challenging his 1980 Texas conviction and death

sentence for murder committed while committing arson.

Hogue's primary complaint on appeal is that the

admission in evidence at the punishment phase of his

trial of a 1974 Colorado guilty plea rape conviction,

which in 1994 a Colorado court set aside finding

Hogue's counsel there had provided constitutionally

ineffective assistance, rendered his death sentence

invalid under Johnson v. Mississippi, 486 U.S. 578,

108 S.Ct. 1981, 100 L.Ed.2d 575 (1988). We reject

this claim, holding it procedurally barred by

Hogue's failure to object at trial, and,

alternatively, because we conclude that under Brecht

v. Abrahamson, 507 U.S. 619, 113 S.Ct. 1710, 123

L.Ed.2d 353 (1993), the admission of the prior

conviction did not substantially influence the

jury's answer to either of the two punishment issues.

We also hold that Hogue is entitled to no relief on

either of the two remaining contentions he raises in

this appeal, one relating to an allegedly biased

juror and the other to the constitutional validity

of treating murder while committing arson as a

capital offense where the death is caused by the

arson. Accordingly, we affirm.

FACTUAL AND PROCEDURAL

BACKGROUND

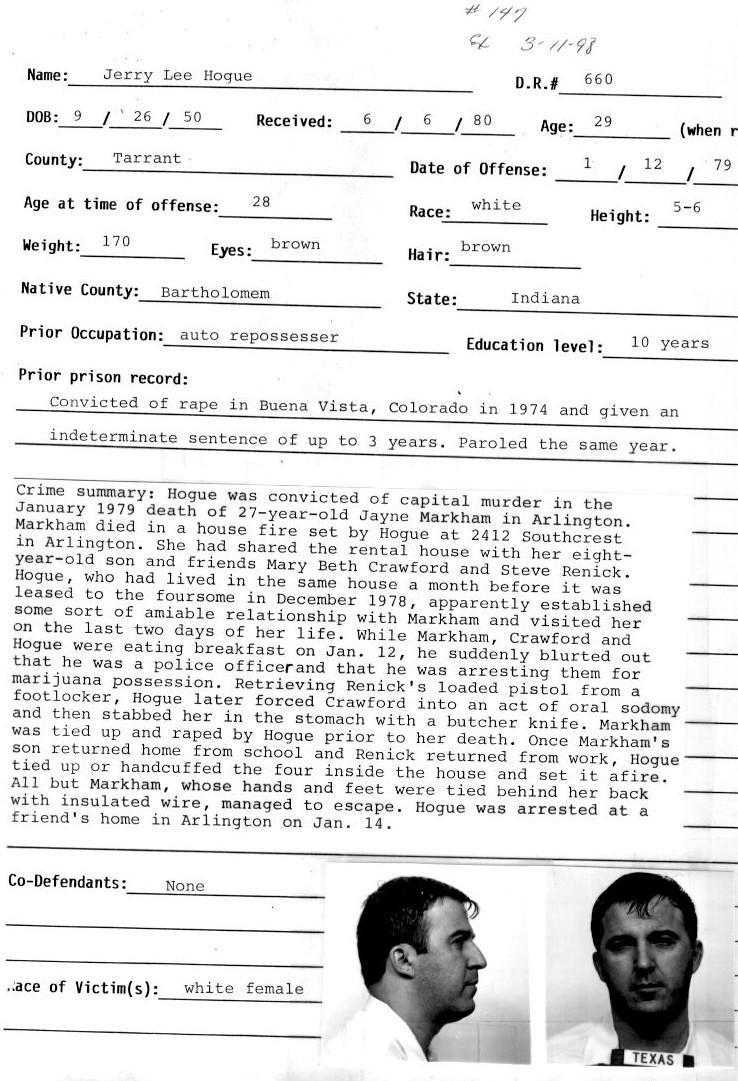

Hogue was indicted for the

January 13, 1979, murder of Jayne Lynn Markham (Markham)

committed in the course of committing arson,

contrary to Texas Penal Code § 19.03(a)(2).

At his March 1980 trial, at which Hogue was

represented by attorneys Coffee and Roe, the jury

found Hogue guilty of capital murder and following

the subsequent punishment hearing answered

affirmatively each of the two special issues called

for by the then version of Texas Code of Criminal

Procedure Art. 37.071, finding that Hogue's conduct

causing Markham's death was committed deliberately

with the reasonable expectation that her or

another's death would result and that there was a

probability he would commit criminal acts of

violence constituting a continuing threat to society.

Hogue was accordingly sentenced to death. On direct

appeal, Hogue was initially represented by attorney

Burns, who, on Hogue's request, was replaced by

attorney Gray. In March 1986, the Texas Court of

Criminal Appeals, en banc, unanimously affirmed the

conviction and sentence (two judges concurred in the

result without opinion), and in October 1986 the

Supreme Court denied certiorari. Hogue v. State, 711

S.W.2d 9 (Tex.Crim.App.), cert. denied, 479

U.S. 922 , 107 S.Ct. 329, 93 L.Ed.2d 301 (1986).

Prior Habeases

There then ensued a lengthy

series of habeas filings by Hogue and his attorneys,

which we outline as follows.

In January 1987, Hogue, through

attorney Alley, filed his first state habeas, which

was amended on February 18, 1987. An evidentiary

hearing was held on this petition on February 24,

1987, at which Hogue was represented by Alley. The

petition was ultimately denied by the Court of

Criminal Appeals on March 18, 1987. In the meantime,

Hogue's execution had been set for March 24, 1987.

On March 20, 1987, Hogue, again through Alley, filed

his second state habeas petition and motion for stay

of execution, each of which the Court of Criminal

Appeals denied on March 22, 1987. On the same day,

Hogue, through Alley, filed in the district court

below his first federal habeas. The district court

granted a stay of execution. On May 7, 1987, Hogue,

pro se, moved to dismiss Alley, alleging that Alley

was not authorized to file the federal habeas

petition. On May 27, Hogue, pro se, moved to amend

the federal petition to add forty-nine additional

grounds. On July 9, 1987, the district court

dismissed the federal petition without prejudice as

having been filed without Hogue's authorization, and

vacated the stay of execution. On August 11, 1987,

Hogue, pro se, filed his third state habeas

application, and on August 19, 1987, attorney Burns

filed a state habeas application on Hogue's behalf.

These latter two applications were treated as

consolidated and on September 25, 1987, were denied

by the Court of Criminal Appeals, which also denied

stay of execution, which had been set for September

29, 1987.

Also on September 25, 1987, Hogue,

through attorneys Mason and Bruder, filed in the

district court below an application for stay of

execution to permit the filing of a habeas petition

in that court, and the district court granted the

stay. On October 17, 1987, the district court issued

its order directing that Hogue, on or before January

8, 1988, file a habeas proceeding in that court

under section 2254 or a state court habeas

proceeding, in which Hogue would "present each and

every claim known to Petitioner or his counsel on

pain of waiver." On January 8, 1988, the district

court, on motions filed that day by Hogue, extended

the January 8, 1988, deadline to January 22, 1988.

On March 29, 1988, the district court, having

learned that Hogue was pursuing a state habeas

proceeding, vacated the stay of execution it had

previously entered and dismissed without prejudice

the federal proceedings.

Previously, on January 22, 1988,

Hogue, through Mason and Bruder, had filed his

fourth state habeas petition (identified in the

state trial court as No. C-3-1330-162441-D).

Evidentiary hearings, at which Hogue was represented

by Mason, were held on this petition on March 24,

1988 (at which Bruder was also present on behalf of

Hogue), and August 8, 1988, and a deposition was

taken (at which Hogue was represented by Mason). The

state trial court made findings of fact and

conclusions of law and recommended denial of relief.

On January 9, 1989, the Court of Criminal Appeals

issued its order denying relief on this habeas (Court

of Criminal Appeals No. 16,907-4), noting that it

had "carefully reviewed the record" and that "the

trial court's findings and conclusions are fully

supported by the record."

On April 13, 1989, Hogue, through

Mason and Bruder, filed another section 2254

petition in the district court below. On April 18,

1989, the district court stayed Hogue's execution,

which had been scheduled for April 20, 1989. On

March 16, 1990, Hogue, through Mason and Bruder,

moved to dismiss or stay the section 2254

proceedings so he could return to state court to

seek relief suggested by Penry v. Lynaugh, 492 U.S.

302, 109 S.Ct. 2934, 106 L.Ed.2d 256 (1989). In July

1990, Mason and Bruder filed a motion to withdraw

from their representation of Hogue as he had claimed

their inadequate representation entitled him to

relief.

Also in July 1990, Hogue, pro se,

filed in the federal proceeding a pleading

complaining of his counsel's failure to investigate

certain claims and, later, a memorandum opposing the

request of Mason and Bruder to withdraw. On August

22, 1990, the district court appointed Mason and

Bruder under the Criminal Justice Act, so they could

be compensated, and also appointed an investigator

to assist them. This order directed that by October

19, 1990, a supplemental pleading be filed asserting

each issue Hogue sought to raise. On November 16,

1990, Hogue, pro se, moved in the federal proceeding

to dismiss Mason and Bruder, and to dismiss his

section 2254 proceeding without prejudice so he

could return to state court. The district court on

March 7, 1991, dismissed the cause without prejudice,

noting Hogue's November 16, 1990, motion.

On March 22, 1991, Hogue, pro se,

filed his fifth state habeas petition (identified in

the state trial court as No. C-3-1647-16241-E). On

August 5, 1991, the state trial court recommended

denial of relief and transmitted the file to the

Court of Criminal Appeals. On September 18, 1991,

the Court of Criminal Appeals entered its order on

this application (identified in the Court of

Criminal Appeals as Writ No. 16,907-05), reciting

that "[a]ll of the allegations have been raised and

rejected either on direct appeal or in previous

applications for writ of habeas corpus" and "[w]e

hold that the applicant's contentions are not only

without merit but have been waived and abandoned by

his abuse of the writ of habeas corpus." The order

goes on to direct the Clerk of the Court of Criminal

Appeals:

"not to accept or file the

instant application for writ of habeas corpus. He is

also instructed not to accept in the future any

applications for a writ of habeas corpus attacking

this conviction unless the applicant has first shown

that any contentions presented have not been raised

previously and a showing is made that they could not

have been presented in any earlier application for

habeas corpus relief."

Meanwhile on September 3, 1991,

Hogue, through attorneys Crocker (whom the state

trial court had appointed to represent Hogue on May

2, 1991) and Owen, tendered for filing in the state

court on Hogue's behalf his sixth state habeas

application (identified in the state trial court as

No. C-3-1647-16241-F). This application, which runs

173 pages exclusive of exhibits, asserts 36 grounds

for relief. On October 17, 1991, the state trial

court signed an order, responsive to the Court of

Criminal Appeals' September 18, 1991, order,

identifying three issues raised in Hogue's sixth

state habeas "which have not been and could not have

been raised in previous proceedings." In response to

a motion filed November 13, 1991, by Hogue, through

Crocker and Owen, the state trial court modified its

October 17, 1991, order by slightly rewording its

statement of the three available issues.

In December 1991, the state trial

court denied a motion filed by Hogue, through

Crocker and Owen, to permit the filing of Hogue's

sixth state habeas petition. On March 6, 1992, the

state trial court issued an order adopting, with

modifications, the state's proposed memorandum,

findings, and conclusions, recommending denial of

relief with respect to the three available issues

identified in the trial court's October 17, 1991,

order as modified (see note 6, supra). The March 6,

1992, order directed that the file be transmitted to

the Court of Criminal Appeals, where it was received

March 11, 1992. On March 16, 1992, the Court of

Criminal Appeals, through its Executive

Administrator, wrote the state trial court with

respect to Hogue's sixth state habeas writ (reflecting

copies being sent to Hogue, Crocker, counsel for the

state, and the state district clerk) as follows:

"Re: Writ No. 16,907-06

Jerry Lee Hogue

Trial Court No. C-3-1647-16241-F

Dear Judge Leonard:

On September 18, 1991, this Court

entered an order citing the above referenced

applicant with abuse of the writ.

The present application does not

satisfy the requirements for consideration set out

in the order described above. Therefore, this Court

will take no action on this writ.

For further information see Ex

parte Dora, 548 S.W.2d 392 (Tex.Cr.App.1977)."

Hogue's execution was thereafter

set for May 28, 1992. There were no further state

court filings.

This Habeas

The instant section 2254 petition

was filed by Hogue, through Crocker and Owen, on May

19, 1992.

It is 184 pages long (and is accompanied by more

than 700 pages of exhibits and by a memorandum which,

together with its own exhibits, occupies more than

400 pages in the record) and raises 33 grounds of

relief. On May 22, 1992, the district court granted

Hogue's requested stay of execution. On June 12,

1992, an amended habeas petition was filed, adding

two grounds for relief, but not otherwise altering

the original petition. On November 2, 1992, the

State filed its answer and motion for summary

judgment. The matter was referred to a Magistrate

Judge for recommendations and proceedings as deemed

appropriate. On March 14, 1994, the Magistrate Judge

issued a 126-page report and recommendations,

recommending denial of all relief. Hogue filed

objections to the report and recommendations. The

district court afforded de novo consideration to all

of Hogue's asserted grounds for relief. On November

16, 1994, the district court entered judgment

denying all relief, together with a thorough and

comprehensive opinion reciting in detail the course

of proceedings at trial and on direct appeal, the

evidence presented at trial, and the course of

Hogue's prior habeases, and addressing and disposing

of all of Hogue's asserted grounds for relief in his

current habeas. Hogue v. Scott, 874 F.Supp. 1486 (N.D.Tex.1994).

On January 18, 1995, the district court denied

Hogue's Rule 59(e) motion with a brief opinion. Id.

at 1545-46.

Offense Circumstances

The Court of Criminal Appeals'

opinion generally describes the circumstances of the

offense:

"The evidence introduced at trial

showed that appellant [Hogue] and his wife rented a

house located at 2412 Southcrest in Arlington on

November 9, 1978. Approximately one month later, on

December 4, 1978, appellant and his wife vacated the

house without turning in their key, leaving a

refrigerator, a round wall ornament and some trash.

The property was cleaned up and on December 24 the

house was leased to Mary Beth Crawford and Jayne

Markham. Living at the house with the two women were

Markham's eight-year-old son and Steve Renick, a

friend of the women.

On a Wednesday, January 10, two

days before the commission of this grisly and brutal

crime, appellant returned to the house. When Markham

answered the door, appellant told her he had lived

in the house and had left a wall hanging at the

house and asked if he could get it. Markham let

appellant in the house and they began conversing.

Apparently some sort of amiable relationship between

Markham and appellant was struck because appellant

stayed at the house for quite a long time that

evening.

On Thursday, appellant again

showed up at the house. Markham had agreed to buy

some used furniture from appellant so she went with

him to pick up the furniture. When they arrived back

at the house, once again appellant stayed for the

duration of the evening. Eventually the women went

to bed and only appellant and Renick were awake.

Appellant asked Renick if he knew where he could get

a gun. Renick showed appellant the gun he kept in

his footlocker. After cleaning the gun, Renick

loaded it and placed it back inside the footlocker.

Appellant was at the house again

early the next morning. Renick went to work and

Crawford took Markham's son to school. On her way

home she stopped at the grocery store. When she

returned home, she prepared breakfast for herself,

Markham and appellant. Crawford noticed that Markham

seemed upset. While the trio were eating breakfast,

appellant suddenly blurted out that he was a police

officer and that he was arresting them for

possession of marihuana.

When the women asked for some

sort of identification, appellant said that he did

not have any with him but that his real purpose was

to arrest Steve Renick because he was a heroin

dealer. Appellant told the women to cooperate, to

stay in his sight all day long and not to talk to

each other. He then had them go into Markham's

bedroom. Appellant left the bedroom and shortly

thereafter the women heard a breaking noise. They

followed the noise and found appellant going through

Renick's footlocker.

Appellant found Renick's gun

inside the footlocker. Appellant pointed the gun at

the women and told them he was going to handcuff one

of them. He proceeded to handcuff Markham; he put

Crawford into a closet. After a period of ten

minutes, appellant opened the closet door. He had

the gun in his hand and was nude from the waist down.

Appellant stepped inside the closet, pointed the gun

at Crawford's head and instructed her to removed her

clothes. When Crawford replied that she would not

and she had venereal disease, appellant backed out

of the closet and shut the door.

A short while later appellant

removed Crawford from the closet and led her into

the dining room. There she saw Markham nude and

blindfolded, lying face down on the floor with her

hands cuffed behind her. Appellant told Crawford to

remove all of her clothes except her underwear and

to lie down beside Markham. After a few minutes,

appellant forced Crawford to commit oral sodomy upon

him. Thereafter, appellant again put the women in

the bedroom. Crawford was put back into the closet

while appellant raped Markham. Then appellant

blindfolded both women and forced both of them to

lay on the bed. He then proceeded to go through

Markham's purse.

Appellant later permitted both

women to get dressed. He instructed the women not to

talk to each other and at a point during the day

when he caught the women talking he took Crawford

into her room and handcuffed her to her bed. At 3:15

p.m., Markham's son returned home from school.

Appellant made him go to his mother's room and

remain there. Around 6:00 p.m., Renick came home.

Appellant, carrying the gun and a pair of handcuffs,

met Renick at the front door. Renick was immediately

handcuffed and led into Markham's bedroom.

Appellant told Renick that he was

a narcotics agent and was arresting him. Appellant

took Renick's wallet and then moved Renick into

Crawford's bedroom where he was handcuffed to the

bed. Over the next few hours appellant moved through

the house, shuffling his prisoners from room to room.

Throughout the evening appellant made numerous

threats to kill them all. At one point appellant led

Crawford into the living room and had her sit on the

couch.

Appellant left the room and when

he returned he was carrying a butcher knife. He

stabbed Crawford in the stomach and then dragged her

into a bathroom. A short time later, he had both

women go back into the living room. There he told

them he was a hit man and had a contract out for

each of them. Appellant then took Crawford into the

third bedroom. By this time Crawford was bleeding

heavily, was in intense pain, and was passing in and

out of consciousness.

Appellant brought Markham into

the room where Renick was now confined. By this time

Renick's hands had been tied to the headboard and

his feet had been bound together. Appellant

proceeded to bind Markham by tying her hands behind

her back, tying her feet together and then taking a

wire and tying her feet to her hands. When Renick

and Markham begged appellant to release them so that

they could take Crawford to the hospital, appellant

said he was a hit man and he was going to kill them

all.

Appellant left the room. Soon the

victims began to smell gasoline. They could hear the

appellant in the attached garage coughing and

sputtering. After a while appellant came back into

the bedroom carrying a Prestone antifreeze can and a

rolled up newspaper. Appellant again told Markham

and Renick that he was going to kill them all. He

then left the room. The victims saw appellant

backing down the hallway, pouring a liquid out of

the antifreeze can. They soon began to smell

gasoline. Suddenly, fire roared through the hallway

and flames began shooting into the bedroom where

Renick and Markham were tied up.

Renick managed to free himself, break a window

and jump outside. He then tried to go back in and

rescue Markham who was screaming but the flames were

too intense. When the screaming stopped, he ceased

his efforts. He then ran to the window of the

bedroom in which Markham's son was sleeping. He was

able to pull the child out of the window. Crawford,

awake at the time of the fire's ignition, managed to

jump out of a bedroom window. She ran next door to

summon help. On her way to the neighbors, she saw

appellant climbing into his car. She ran to the

neighbors' house and rang the doorbell. The

neighbors found her collapsed on the ground.

Emergency vehicles responded to

the fire call at 1:14 a.m. When they reached the

scene, the house was fully involved. Markham's body

was found by fireman inside the house. Her hands and

feet had been tied behind her back, leaving her body

in a crouched position. An autopsy showed that her

hands and feet were tightly bound with insulated

wire.

Police found a Prestone

antifreeze container sitting just inside the doorway

of the laundry room. It smelled heavily of gasoline.

They also found two sections of garden hose on the

floor of the garage lying next to a vehicle that had

been parked in the garage. These also smelled of

gasoline. A fire investigator concluded that more

than two gallons of gasoline had been used to start

the fire. He determined that the fire had been

deliberately set." Hogue, 711 S.W.2d at 10-12 (footnote

omitted).

The testimony, witness by witness,

is described in greater detail in the district

court's opinion. Hogue v. Scott, 874 F.Supp. at

1500-1511. Hogue testified at the guilt-innocence

stage--though not at the punishment stage--and, as

the district court observed, his rendition of the

events "was virtually a reversal of the roles other

witnesses assigned to Hogue and Renick." Id. at

1509.

Hogue stated that Markham wanted

to get Renick out of the house as white powder had

been found in his footlocker and she thought he was

dealing drugs. Consequently, when Renick returned to

the house from work about 6:00 p.m. Friday, January

12, 1979, Hogue came up behind Renick and put his

knuckle in Renick's back, making Renick think he had

a gun, and under the threat of this imaginary gun

forced Renick to lie down, and then handcuffed him.

He then took Renick to a bedroom,

removed the handcuffs and re-handcuffed Renick to

the bed. Later, after consulting with Markham and

after Renick promised to leave, Hogue unhandcuffed

Renick. Some time later, as Hogue and Markham were

talking, Renick appeared with a pistol in hand and

told them to go into a bedroom, which they did.

Hogue then heard Crawford and Renick talking about

dope, heard Crawford scream, and saw her run, bent

over, into Renick's bedroom.

Holding the gun on Markham and

Hogue, Renick tied them up. Sometime later Renick

untied Hogue and forced him to siphon gas out of a

vehicle in the garage and put it in a Prestone

antifreeze can and some milk cartons. Renick then

told Hogue to spill the gas, Hogue refused, and

Renick took him back to the bedroom, where Markham

was tied, and retied him. Renick left the room.

Later, Hogue smelled gas. He

broke the bedposts to which he was tied and began

untying Markham. Renick appeared in the door, Hogue

kicked at him and missed, and his momentum carried

him into the hallway; Renick "back[ed] off down the

hall," and "brought the gun up." Hogue then ran out

of the house. When he reached the street, he saw the

house suddenly go up in flames. He thought he saw

Renick standing at the side of the house. Hogue

jumped in his car and drove off.

After a thorough review of the

evidence, we are in full agreement with the district

court's conclusion that Hogue's version of the

events "when weighed against the other evidence in

the case, is so lacking in credibility that no

reasonable trier of fact would accept it." Hogue v.

Scott at 1509.

Hogue was found by the police

some twenty-four hours after the fire, shortly after

11:00 p.m. Sunday, January 14, 1979, alone in a

friend's small upstairs apartment, which was totally

dark, hiding, fully clothed, in the shower stall

behind the closed shower door in the bathroom.

Though the police had announced

their presence and stated they were looking for

Hogue, he had remained wholly silent and hidden.

Hogue knew the police were looking for him, and he

had made no attempt to contact them (or the fire

department or emergency medical services or any

other authority). He gave no explanation for this.

Hogue has offered no explanation

for the testimony of Markham's son--called as a

witness by Hogue--that Hogue held a pistol on

Markham and Crawford before Renick returned from

work late Friday afternoon, January 12, then went to

the front door with the gun when Renick's truck was

heard to drive up, stated to Renick "I am arresting

you for selling marijuana," and returned with the

gun and with Renick handcuffed, after which Renick

was handcuffed to the bed.

The boy also testified that

Renick removed him from the burning house. The two

neighbors testified as to Crawford and Renick's

fleeing to their house, Renick's desperate efforts

to save Markham and the boy, Crawford's anguish at

their fate and her spontaneous statements to each of

the neighbors concerning her near fatal stabbing by

Hogue: "I don't know why he stabbed me. I don't know

why he did it. I don't know him," and "I don't

understand why he did this to me. I don't even know

him."

It was clearly established and

undisputed that Crawford and Renick had known each

other well over a year prior to the events in

question, while prior thereto she and Hogue were

total strangers each to the other. Similarly,

Crawford's and Renick's statements to the neighbors,

and to the police who shortly arrived, were excited

utterances and were consistent with their trial

testimony, which was also corroborated by their

physical condition (e.g., Renick's arms were cut and

bleeding, his hair and beard were singed, and he had

no shoes on; Crawford was suffering a near-fatal

stab wound) and actions then as testified to by

other witnesses, including the police and the

neighbors.

Prior Conviction Impeachment

In cross-examination of Hogue (at

the guilt-innocence stage), the state was permitted

to ask him, for impeachment purposes only, whether

he had been convicted in September 1974 for rape in

Colorado in cause No. 6785, to which Hogue replied

"I plead guilty to a fourth class felony of rape,

yes, sir" and went on to state that he had served

ninety days of his three-year sentence (he

subsequently admitted he had later served an

additional sixty days of that sentence).

Defense counsel objected on the

sole ground that under Texas "Code of Criminal

Procedure[s] [art.] 38.29" the conviction "is not a

final conviction."

Just before Hogue took the stand, defense counsel in

a hearing out of the presence of the jury had

unsuccessfully sought to preclude cross examination

of Hogue in respect to this conviction on the ground

that the conviction was not final, because Hogue's

sentence was probated and probation had been

completed. In support, defense counsel placed before

the court as Defendant's Exhibit A (which the court

admitted for purposes of the hearing on

admissibility of the conviction) the record of the

proceedings in Colorado cause No. 6785, reflecting

that Hogue was charged in an eight-count information

filed May 6, 1974, count three of which alleged rape

on May 3, 1974, of Claudia Hogue;

on August 19, 1974, Hogue, represented by counsel

Hilgers and "[a]fter being advised of his rights as

provided under Rule 11," pleaded guilty to the rape

count, the two then-remaining other counts (second

degree kidnaping and theft over $100) in cause No.

6785 were dismissed (as were all the four other

pending informations against Hogue, Nos. 6534, 6322,

6324 & 6325); on September 23, 1974, Hogue was

sentenced to three years on the rape conviction, and

the court denied probation; on November 27, 1974,

Hogue, through counsel Hilgers, filed a motion to

modify the sentence based on "very favorable reports"

from the prison (reformatory), copies of which were

filed with the motion; on December 23, 1974, the

Colorado court, reciting that it had "read the

recommendations from the reformatory," granted the

motion to modify and placed Hogue on probation for a

two-year period; on April 24, 1975, the probation

department filed a complaint charging that Hogue had

violated his probation in four respects; on April

28, 1975, Hogue, represented by counsel Truman,

pleaded not guilty to the probation violation

complaint; another probation violation complaint was

filed by the probation department on August 6, 1975,

alleging August 3, 1975, law violations (sexual

assault and burglary); on November 10, 1975,

attorney Gray appeared for Hogue (apparently not the

same Gray who later represented him on direct appeal

of his 1980 conviction); on November 24, 1975, the

August 6, 1975, probation complaint based on

violation of law was withdrawn; on December 8, 1975,

Hogue, represented by Gray, pleaded guilty to and

was found guilty of probation violations in cause

No. 6785, the three-year sentence in that cause was

reimposed, and Hogue was ordered to the state penal

institution, with credit for 91 days served there

and for 125 days in local confinement (two other

criminal cases against Hogue, Nos. 7638 and 7487,

were also then dismissed); on February 9, 1976,

Hogue, through Gray, moved to modify the sentence in

No. 6785 by placing Hogue on probation; on March 1,

1976, the Colorado court granted that motion and

ordered that "the balance of" Hogue's "sentence" be

suspended and that he be released from custody and

placed on probation for a period to expire December

23, 1976; on January 6, 1977, the Colorado court

ordered the probation supervision discontinued and

terminated the No. 6785 proceedings against Hogue

because the period of his probation had expired.

None of this evidence was placed (or sought to be

placed) before the jury.

Defense counsel's motions in

limine had sought to establish with respect to this

1974 Colorado rape conviction that "the Defendant

was placed on probation which probation was

successfully completed and terminated on the 6th day

of January, 1977." At argument before the court, out

of the presence of the jury, counsel contended,

after the court had indicated that it would allow

Hogue to be impeached by the prior conviction, "our

objection to the court's ruling comes from Code of

Criminal Procedure 39.29 [sic], where it says in

that Article, that," and counsel then read from

Tex.Code Crim.Proc. art. 38.29 (quoted in note 11,

supra), concluding with the language thereof

indicating that a probated sentence was not

admissible for impeachment unless "the period of

probation has not expired." Counsel went on the

argue that the Colorado records showed that Hogue's

"probation was terminated by the court on January

the 5th, 1977" and "[w]e would take exception to the

Court's ruling based upon Article 38.29 and on

Defendant's Exhibit A that has been admitted before

the court."

The court ruled that the prior

conviction was admissible as impeachment because

Hogue's sentence was not originally probated and he

served time under that sentence in the state penal

institution, and also because when his sentence was

later first probated that probation was revoked and

he again served time in the state penal institution

under the original sentence. The trial court also

instructed the jury, in its charge at the guilt-innocence

stage, that the prior conviction evidence "cannot be

considered by you against the defendant as any

evidence of his guilt in this case" and "was

admitted before you for the purpose of aiding you,

if it does aid you, in passing upon the weight you

will give his testimony, and you will not consider

the same for any other purpose."

There was no objection to this instruction, nor any

request for other or further instructions in that

respect.

Sentencing Evidence

The testimony at the punishment

phase is outlined, witness by witness, in the

district court's opinion. Hogue v. Scott, 874 F.Supp.

at 1509-1511.

The prosecution commenced by

introducing a copy of the September 23, 1974,

Colorado court judgment convicting Hogue of rape,

based on his guilty plea, and sentencing him to

confinement for an indeterminate term not to exceed

three years. Out of the presence of the jury, the

state had previously announced its intention to

offer this evidence, and Hogue, personally, had

stated "I have no objection," as did also defense

counsel. At no point in the trial was any objection

ever made to this evidence; nor was any such

objection ever urged on appeal.

Lieutenant Detective Diezei of

the Boulder, Colorado Police Department, who had

been with that organization some fifteen years,

testified that in that capacity he had occasion to

know that Hogue's reputation in that community for

being a peaceable and law-abiding citizen was bad,

and that he first heard about Hogue "in

approximately 1970."

Sara Sampson testified that she

was "from out of state," that she knew Hogue, having

first met him "about ten years ago," and that in the

community in which she knew him his reputation for

being a peaceable and law-abiding citizen was bad.

On cross-examination, Sampson identified certain

photographs as being of Hogue, his ex-wife Claudia,

and his daughter Shawna.

Karen Hightower testified that on

July 25, 1976, when she was living in an apartment

in Richland Hills and was going through a divorce,

she met Hogue in the apartment building parking lot

when her car wouldn't start and he offered to help,

loaning her jumper cables. Subsequently, she went

out with him. She later told Hogue she did not want

to see him anymore, and he got angry.

Thereafter, on August 2, 1976,

Hogue telephoned her, stated that he wanted "for us

to part friends," and asked her to go with him to

get a hamburger and meet his uncle, who Hogue said

was expecting them. Not wanting to hurt his feelings,

she accepted, and they went in Hogue's car to get a

hamburger and then drove into the country,

supposedly towards the uncle's house. Hogue stopped

the car, pulled a long knife, grabbed Hightower,

threatened to kill her, made her commit sodomy, and

raped her twice (there was no ejaculation). On

cross-examination, she admitted that the rape case

growing out of this incident was no longer pending

as, following a mistrial therein, she "chose not to

go through a retrial."

Cross-examination also revealed that Hightower had

been convicted of fraud in 1978 and that her

exhusband had custody of her daughter.

The prosecution's final

punishment stage witness was psychiatrist Dr.

Grigson (also spelled in the record as Gregson). Dr.

Grigson had not examined or interviewed Hogue, or

examined any records or the like pertaining to him.

In response to a lengthy hypothetical question (occupying

some 192 lines in the record), which set out

hypothetical circumstances paralleling the

circumstances of the instant offense and those

immediately leading up to it as reflected by the

prosecution's evidence (some 177 lines), and also

mentioned a previous rape conviction (2 lines), and

a rape such as discussed by Karen Hightower (11

lines), Dr. Grigson testified that a person so

described "certainly would present very much of a

continuing threat to society," and would be such

even if confined in a penal institution. Cross-examination

was almost entirely focused on what defense counsel

asserted was the impropriety of predicting future

dangerousness, especially solely on the basis of a

hypothetical question, on asserted professional

criticism of Dr. Grigson for doing so, and on his

frequent testifying and related remuneration. No

counter-hypotheticals were posed to Dr. Grigson.

The defense put on psychologist

Dr. Dickerson. He, too, had not examined or

interviewed Hogue, or examined any records or the

like pertaining to him. The bulk of Dr. Dickerson's

testimony was that future dangerousness could not be

predicted, and that such predictions were wrong two

out of three times; that it was especially improper

to so predict without examination of the individual

concerned and solely on the basis of a hypothetical

question; and that a committee of the American

Psychiatric Association had condemned that practice.

On cross-examination by the state,

Dr. Dickerson was unwilling to state that future

dangerousness could be predicted for anybody, no

matter what they had done in the past. A person's

past dangerousness, no matter how clearly evidenced,

simply did not justify predicting future

dangerousness. Subsequently, Dr. Dickerson was

recalled by the defense, and based on a hypothetical

testified that the Parole Board was very reluctant "to

grant parole to someone with a history of that sort."

Apart from this statement, Dr. Dickerson gave no

testimony about Hogue personally or by hypothetical.

On cross-examination by the prosecution, Dr.

Dickerson admitted that probably a majority of

murderers who receive life sentences are granted

parole.

The remaining defense punishment

phase witnesses were Becky Hogue and Mary Ebel.

Becky Hogue testified that she had known Karen

Hightower "since about '72 or '76" and that her

reputation for being a truthful person was very bad.

Mary Ebel testified that Hogue

was her youngest son, and she identified three

photographs as being of Hogue, his ex-wife Claudia,

and his daughter Shawna.

Ebel testified that Claudia was "the injured party

in the rape case that sent Jerry to the Colorado

State Reformatory," that the pictures were taken at

that Reformatory "around January of '76" while Hogue

was there "after he had already plead guilty and

been sent to the Colorado state Reformatory." Ebel

said she took Claudia to visit Jerry in the

Reformatory because Claudia "has no other way to go."

This was Ebel's only testimony at the punishment

stage.

The prosecution did not

cross-examine her. The three pictures were

introduced in evidence. In one, Claudia and Hogue

are sitting right next to each other (their bodies

touching), Hogue's arm around Claudia and young

Shawna sitting apparently half on the lap of each;

in another, Hogue is standing holding Shawna on his

right and Claudia is on his left and slightly behind

him with both her arms around him; the remaining

picture shows Claudia and Hogue standing next to

each other (their bodies touching) and does not

include Shawna. In each picture all the subjects are

smiling.

The jury was instructed that in

answering the punishment issues it could consider

the evidence introduced at the guilt-innocence stage

of the trial, as well as that introduced at the

punishment stage.

DISCUSSION

I. Admission of Colorado

Conviction at Sentencing

The first of the three issues

raised by Hogue on this appeal is stated in his

appellant's brief as follows: "Did the admission of

Mr. Hogue's invalid prior felony conviction from

Colorado at the sentencing phase of his Texas

capital murder trial violate the Eighth and

Fourteenth Amendments under Johnson v. Mississippi,

486 U.S. 578, 108 S.Ct. 1981, 100 L.Ed.2d 575

(1988), and was he harmed by the violation?"

Hogue does not argue (and did not argue below) that

any invalidity in his 1974 Colorado conviction

renders his Texas capital murder conviction subject

to attack under the Constitution or laws of the

United States (or, indeed, in any way now subject to

attack).

Consequently, we do not consider any such question.

Colorado Court 1994 Action

In late December 1992, some seven

months after the instant section 2254 petition was

filed, Hogue, through counsel, commenced proceedings

in the Colorado trial court in which he had been

convicted, on the guilty plea, of rape in September

1974, to set that conviction aside. In an order

entered June 6, 1994, the Colorado court (a judge

who had not previously been involved in Hogue's

case) set aside Hogue's 1974 conviction (cause No.

6785), finding that Hogue's then counsel, Hilgers,

had rendered constitutionally ineffective assistance.

A copy of the Colorado court's order and memorandum

opinion was filed with the district court below on

June 7, 1994.

The Colorado trial court's order,

invoking the standards of Strickland v. Washington,

466 U.S. 668, 104 S.Ct. 2052, 80 L.Ed.2d 674 (1984),

and Hill v. Lockhart, 474 U.S. 52, 106 S.Ct. 366, 88

L.Ed.2d 203 (1985), found that Hogue's counsel,

Hilgers, rendered Hogue ineffective assistance in

connection with his August 19, 1974, plea of guilty

to rape in cause No. 6785.

This determination was based on findings that

Hilgers, an attorney licensed in 1972 (and disbarred

in 1980) who had never tried a felony case, "conducted

no investigation and talked to no witnesses, other

than talking to the defendant" and waived a

preliminary hearing, all without any "reasonable

tactical purpose." Hilgers had Hogue take a

polygraph test, the results of which were adverse to

Hogue.

The Colorado court found that "[b]efore

the polygraph exam, he [Hilgers] believed the

defendant's version of the facts, and expected that

the polygraph would establish the defendant's

innocence," but that "[a]fter receipt of the

polygraph results shortly after June 28, 1974,"

Hilgers became "panicky" and decided to dispose of

the case "at almost any cost, because he had faith

in the polygraph and no longer believed his client."

Subsequently, the prosecution made the offer to

Hilgers on the basis of which Hogue ultimately

pleaded guilty (see note 24, supra), Hilgers

communicated the offer to Hogue, and "took the

position that the defendant must accept the offer

because Mr. Hilgers felt there was a substantial

likelihood of conviction."

However, Hilgers "was focused

primarily on his own desire to avoid trial," "his

advice was not based on an informed judgment," and "his

recommendation was not the product of an intelligent

choice among reasonable alternative courses." Hogue

"reluctantly accepted the advice from Mr. Hilgers,

although, to this date, he has always maintained his

innocence." The Colorado court concluded that "there

is a reasonable probability that, if competent

counsel had developed the facts, he or she would not

have recommended a guilty plea and the defendant

would not have pled guilty" and that "there was a

reasonable probability that at a trial on the charge

the defendant would have been acquitted."

The Colorado Court, however, did

not find that no competent counsel would have

advised Hogue to plead guilty. The court stated it

was "not unmindful of the prosecution's argument

that, in the context of the plea bargain package,

the defendant can be said to have done quite well.

However, the issue is not that, but whether this

rape conviction is valid. And what is important is

not outcome alone."

The court also remarked, in

reference to cause No. 7304, in which Hogue was

later acquitted, "[o]f course, there was less at

risk in that case than there was for the defendant

here [in No. 6785]." Nor did the Colorado court find

that Hogue was in fact innocent of the rape charge

in cause No. 6785. It stated that "[t]he Court has

no way of knowing whether Claudia Hogue's

allegations in this case were true. And the Court

does not mean to demean her in any way by this

ruling."

At the end of its opinion, the

Colorado trial court stated "[f]urther, because the

defendant was ineffectively represented at the plea

hearing, his plea is invalid under Boykin [v.

Alabama, 395 U.S. 238, 89 S.Ct. 1709, 23 L.Ed.2d 274

(1969) ], as well." This constitutes the Court's

only discussion of Boykin, and the opinion contains

no recitation of facts relevant to Boykin, as

distinguished from Strickland or Hill.

There is no suggestion the court

taking Hogue's guilty plea did not personally advise

him on the record, and in open court in the presence

of his counsel, of all his relevant constitutional

rights, of the elements of the offense, and of the

range of punishment to which his plea exposed him,

and of every other constitutionally required matter.

Nor is there any finding that Hilgers had failed to

advise Hogue, or had incorrectly advised him, as to

any of such matter. The Colorado court's 1994 order

makes no reference to (or description of) anything

that transpired or did not transpire at the August

19, 1974, hearing other than that Hogue then pleaded

guilty and his plea was accepted.

The court's Boykin conclusion

appears to be nothing more than what it regarded as

necessarily following from its finding that Hilgers,

based on a professionally inadequate investigation,

had erroneously advised Hogue that "there was a

substantial likelihood of conviction" and thus "encourag[ed]

the defendant to accept the plea bargain offer," but

"did not give the defendant sufficient information

to make an intelligent choice at the same time

misleading the defendant to believe that he had,"

although "the investigated evidence" would have

shown that "Hilgers had a winnable case for the

defendant," and that there was a reasonable

probability Hogue would otherwise not have pleaded

guilty.

The Colorado court also

determined that Hogue's failure to attack his 1974

conviction until 1992 was within the Col.Rev.St.

(1986) § 16-5-402(2)(d) "justifiable excuse or

excusable neglect" exception to the otherwise

applicable three-year limitation period for such

attacks provided in Col.Rev.St. (1986) 16-5-402(1).

The court concluded that although "there were no

outside circumstances preventing an earlier

challenge by Mr. Hogue's lawyers,"

and "[n]one of the material evidence has been

destroyed," nevertheless "[w]hen the defendant's

subsequent lawyers [those after Hilgers] did not

make the claim now asserted, it is inconceivable

that their failure can be characterized as the

culpable neglect of the defendant."

District Court

The district court below, in its

November 1994 opinion, noted that Respondent (the

State) had waived exhaustion, and accepted the

waiver, though observing it was not bound to do so.

Hogue v. Scott at 1512. The court accepted the

Colorado court's 1994 determination that Hogue's

1974 rape conviction was constitutionally invalid,

but held "there are multiple reasons" why the

admission of evidence of that conviction at Hogue's

sentencing did "not provide a meritorious ground for

relief." Id. at 1516. The court held that Hogue's

claim was procedurally barred because it was first

raised in Hogue's sixth (and last) state habeas

which the Court of Criminal Appeals refused to act

on because of its previously having cited Hogue for

abuse of the writ in its denial of his fifth state

habeas, and Hogue had not shown either cause for

this default or resulting actual prejudice. Id. at

1512-15, 1522. See also id. at 1545-56 (January 1995

order overruling post-trial motion).

The district court further held

that Hogue's claim in this regard was also

independently procedurally barred by his failure to

object at trial to the admission of the evidence,

and that Hogue had not shown either any cause for

this failure nor resulting actual prejudice. Id. at

1522-23. Finally, the district court concluded that

under Brecht any error in the admission at

sentencing of the Colorado conviction was harmless,

noting that "the evidence, independent of the

Colorado conviction, in support of the findings the

jury made at the punishment phase of the trial was

so forceful that the possibility of actual prejudice

resulting at that phase of the trial from the

mentions of the conviction is negated" and "[t]he

mentions of the Colorado conviction did not have a

substantial or injurious effect in determining the

jury's verdict at either phase of the trial." Id. at

1521-22.

Abuse of the Writ

In finding a procedural bar on

the basis of abuse of the writ, the district court (id.

at 1515) relied on our October 13, 1994, opinion in

Hicks v. Scott, 35 F.3d 202 (5th Cir.1994), which

held that where a claim was raised only in a Texas

habeas that the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals took

no action on pursuant to an earlier finding of abuse

of the writ, this constituted a procedural bar to

consideration of that claim on federal habeas as "[t]he

Texas courts have a history of regular application

of the abuse of the writ doctrine."

However, on motion for rehearing

in Hicks, the state apparently conceded that the

abuse of the writ doctrine was not then followed

with sufficient regularity in Texas to constitute a

procedural default which would bar federal habeas

relief, and on March 20, 1995, our original opinion

in Hicks was withdrawn and a new unpublished opinion

was issued in its stead which reached the same

ultimate result but did not address the abuse of the

writ issue. Hicks v. Scott, No. 94-10302, 5th Cir.,

March 20, 1995 (unpublished). On the same day, we

held in Lowe v. Scott, 48 F.3d 873 (5th Cir.1995),

that because the Texas abuse of the writ doctrine

"has not been regularly applied" it could not

function as a procedural default to bar federal

habeas review. Id. at 876. In Lowe we relied on the

statement in the Court of Criminal Appeals' opinion

in Ex parte Barber, 879 S.W.2d 889, 891 n. 1 (Tex.Crim.App.1994),

cert. denied, 513 U.S. 1084 , 115 S.Ct. 739,

130 L.Ed.2d 641 (1995), that it would be

sound policy to apply the abuse of the writ doctrine

"in the future." Lowe at 876. The district court,

however, did not have the benefit of our opinion in

Lowe or of the withdrawal of our original opinion in

Hicks.

We agree with the district

court's observation that it is "quite clear that

Hogue has pursued a course of manipulating, and

abusing, the writ process to the end of gaining

additional time." Hogue v. Scott, at 1546. We

likewise agree with the district court that Hogue

has not shown cause for his abuse (either generally

or with respect to the instant claim regarding the

Colorado conviction). Accordingly, and given that

Texas courts had unquestionably applied the abuse of

the writ doctrine in other published opinions (see,

e.g., cases cited in note 33, supra ), the district

court correctly observed that Hogue had "fair

warning that he was running the risk of a ruling of

abuse of the writ." Id. at 1545.

Moreover, on Hogue's second trip

to the district court below in which he had procured

a last minute stay of execution, the Court on

October 17, 1987, had advised Hogue to file by

January 22, 1988, in federal or state court, a

habeas petition presenting "each and every claim

known to Petitioner or his counsel on pain of waiver."

Further, there is nothing to suggest that the Court

of Criminal Appeals' invocation of the abuse of the

writ doctrine in Hogue's case was any kind of ploy

to avoid a difficult federal issue or was otherwise

in any sense unfair.

Nevertheless, that a state rule

of procedural default be regularly applied--not

merely applied somewhat more often than not--is

essential in order for it to serve as a per se bar

to otherwise available federal habeas relief, and,

as we held in Lowe, the Texas abuse of the writ

doctrine (as applied prior to 1994) does not meet

this test.

Accordingly, the Texas court's abuse of the writ

ruling does not of itself suffice to bar Hogue from

federal habeas relief.

Failure to Object at Trial

The district court held that

Hogue's claim as to the admission at the sentencing

phase of his trial of evidence of the Colorado

conviction, because it was void due to Hogue's

counsel's having rendered him ineffective assistance,

was procedurally barred by his failure to object at

trial to that evidence as required by the Texas

contemporaneous objection rule. Hogue v. Scott, at

1522-23. As the district court correctly observed, "Hogue,

both personally and through his counsel, expressly

told the state trial judge that Hogue had no

objection to the receipt into evidence at the

punishment phase of the trial of proof of Hogue's

Colorado conviction." Id. at 1522.

The district court further correctly determined that

"Hogue has made no plausible suggestion of a valid

cause for his failure to timely object on the ground

that his Colorado conviction was invalid." Id. at

1523.

Hogue challenges the district

court's invocation of failure to comply with the

Texas contemporaneous objection rule as a procedural

bar on essentially three grounds.

First, Hogue makes a brief,

passing assertion that this was not adequately

raised by the state below. We disagree. In its

supplemental answer filed below on July 7, 1994, the

state specifically and adequately pleaded the

procedural bar arising from Hogue's failure to

object at trial as required by the Texas

contemporaneous objection rule (citing pertinent

Texas and federal authority).

Second, Hogue argues that the

Texas contemporaneous objection rule is (or was) not

" 'strictly or regularly followed,' " as is required

for a default thereunder to bar federal habeas

relief, Johnson v. Mississippi, 486 U.S. 578,

586-88, 108 S.Ct. 1981, 1987, 100 L.Ed.2d 575

(1988), or at least that it is (or was) not so

followed with respect to this character of claim. We

reject this contention.

The Texas contemporaneous

objection rule was already well established as long

as thirty-five years ago, see, e.g., Freeman v.

State, 172 Tex.Crim. 389, 357 S.W.2d 757, 758

(1962),

and for more than twenty years we have on numerous

occasions invoked noncompliance with it as a basis

on which to deny federal habeas relief. And, on

several occasions we have expressly held that it was

followed with sufficient regularity for this purpose.

In denying habeas relief on this basis in St. John

v. Estelle, 544 F.2d 894 (5th Cir.1977), we observed

that "Texas' contemporaneous objection rule furthers

a valid state interest." Id. at 895. This opinion

was adopted by the en banc court with the addition

of a citation to Wainwright v. Sykes, 433 U.S. 72,

97 S.Ct. 2497, 53 L.Ed.2d 594 (1977). St. John v.

Estelle, 563 F.2d 168 (5th Cir.1977) (en banc), cert.

denied, 436 U.S. 914 , 98 S.Ct. 2255, 56 L.Ed.2d

415 (1978). In Bass v. Estelle, 705 F.2d 121

(5th Cir.), cert. denied, 464 U.S. 865 , 104

S.Ct. 200, 78 L.Ed.2d 175 (1983), a federal

habeas challenging a "spring of 1980" Texas

conviction and death sentence, we specifically

rejected a contention that the Texas contemporaneous

objection rule was not sufficiently "regularly

applied" so that noncompliance with it could not bar

federal habeas relief. Id. at 122.

In doing so, we recognized that

the "regularly applied" standard was met despite

exceptions for instances where the law in effect at

the time of trial would have precluded successful

objection. Id. We also held that "an occasional act

of grace by the Texas court in entertaining the

merits of claim that might have been viewed as

waived by procedural default" did not "constitute

such a failure to strictly or regularly follow the

state's contemporaneous objection rule" as to

generally preclude reliance thereon to bar habeas

relief. Id. at 122-123.

We reviewed the matter at some

length in Amos v. Scott, 61 F.3d 333 (5th Cir.),

cert. denied, --- U.S. ----, 116 S.Ct. 557, 133 L.Ed.2d

458 (1995), and, reaffirming the holdings of Bass,

concluded that "Texas courts apply the

contemporaneous objection rule strictly and

regularly." Amos at 341. We noted that the question

was whether the rule "is strictly or regularly

applied evenhandedly to the vast majority of similar

claims," id. at 339, that the presence of exceptions

for a right not legally recognized at time of trial

and for certain cases of fundamental error did not

alter this conclusion, id. at 343-344, and that "the

relatively few occasions ... in which it might be

said that the TCCA [Texas Court of Criminal Appeals]

has disregarded the rule and its exceptions are not

sufficient to undercut the overall regularity and

consistency of their application and thus the

adequacy of the state procedural bar." Id. at 345.

To the same effect are Sharp v. Johnson, 107 F.3d

282, 285-86 (5th Cir.1997), and Rogers v. Scott, 70

F.3d 340, 344 (5th Cir.1995), cert. denied, --- U.S.

----, 116 S.Ct. 1881, 135 L.Ed.2d 176 (1996).

Texas courts, and this Court,

have long applied the Texas contemporaneous

objection rule to bar claims that a conviction

introduced in evidence without objection (or with

objection only on another ground) was invalid.

Decisions of the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals

doing so include the following:

Ex parte Gill, 509 S.W.2d 357,

359 (Tex.Crim.App.1974) (state habeas attacking 1970

conviction and sentence on basis that at trial

evidence of revocation of probation for earlier

offense was introduced, despite the fact that the

revocation was invalid due to lack of counsel; held

that although the revocation was invalid for lack of

counsel, the failure to object at trial waived the

error);

Wright v. State, 511 S.W.2d 313, 315 (Tex.Crim.App.1974)

(on appeal from revocation of probation for 1973

conviction for second offense DWI, a felony, treated

as an appeal from 1973 conviction and sentence,

rejects challenge to first offense conviction, a

1970 misdemeanor DWI, on grounds that defendant was

not afforded counsel in the 1970 case, because of

failure to object to the evidence of the prior

conviction);

Ex parte Sanders, 588 S.W.2d 383, 384-5 (Tex.Crim.App.1979)

(en banc) (state habeas challenge to conviction

enhanced by prior felony conviction, it being

claimed that the prior felony was void because of

lack of counsel; habeas denied because of failure to

object to the proof of the prior felony; "[f]ailure

to object to proof of a void conviction has been

held to constitute waiver ... [W]e hold that

petitioner's failure to object when the complained

of prior conviction was offered into evidence

constituted a waiver of the claimed right");

Ex parte Reed, 610 S.W.2d 495, 497 (Tex.Crim.App.1981)

(en banc) (state habeas challenge to 1972 conviction

and sentence on grounds, among others, of admission

in evidence at the sentencing phase of prior

convictions which were allegedly void because of

ineffective assistance of counsel; "[w]ith regard to

the claim that the allegedly void prior convictions

were introduced at his trial ... as part of

petitioner's prior criminal record, we observe that

there was no objection to the introduction of the

evidence of the prior convictions at the time the

exhibits were offered. Therefore, he waived any

claim he may now assert"); Hill v. State, 633 S.W.2d

520, 523-25 (Tex.Crim.App.1981) (en banc) (appeal of

conviction and sentence enhanced by 1963 conviction;

pending this appeal, the 1963 conviction was set

aside because the defendant was without counsel;

held instant conviction and sentence affirmed

because there was no objection at trial to the

evidence of the 1963 conviction, citing numerous

prior cases; "we hold that the failure to object at

trial to the introduction of proof of an alleged

infirm prior conviction precludes a defendant from

thereafter attacking a conviction that utilized the

prior conviction");

Ex parte Ridley, 658 S.W.2d 177 (Tex.Crim.App.1983)

(en banc) (habeas attack on both 1967 burglary

conviction and 1976 robbery conviction in which the

sentence was (without objection) enhanced by the

1967 burglary conviction; habeas granted as to the

1967 conviction because the same jury that

determined guilt also determined competence to stand

trial; habeas denied as to 1976 conviction and

enhanced sentence because "[t]he failure to object

at trial to the introduction of an infirm prior

conviction precludes the defendant from thereafter

collaterally attacking the conviction that utilized

the infirm prior conviction"); Ex parte Cashman, 671

S.W.2d 510 (Tex.Crim.App.1983) (en banc) (state

habeas attacking 1977 robbery conviction and

sentence enhanced by 1969 Colorado conviction; the

Colorado conviction was pursuant to a guilty plea;

there was no objection to the evidence of the

Colorado conviction at the 1977 trial or on direct

appeal; after the 1977 conviction and sentence were

affirmed on direct appeal, the defendant filed a

motion in the Colorado court to set the Colorado

conviction aside because the guilty plea was not

intelligently and knowingly entered, no factual

basis was shown to support the plea and defendant

did not receive effective assistance of counsel; the

Colorado court granted the motion; habeas as to the

1977 conviction and sentence was denied because

there was no objection at trial to the Colorado

conviction).

The decisions of this Court have

likewise long recognized that federal habeas relief

sought on the basis that an invalid prior conviction

was put in evidence at the petitioner's Texas trial

is properly denied where the petitioner did not

object at his trial to the evidence of the prior

conviction as required by the Texas contemporaneous

objection rule. In McDonald v. Estelle, 536 F.2d 667

(5th Cir.1976), we affirmed a grant of habeas relief

as to a 1973 Texas conviction and fifteen-year

sentence because of the introduction at the

punishment phase of the trial of a 1960 Arkansas

theft conviction, based on a guilty plea, which we

found constitutionally invalid because the defendant

was indigent, did not have counsel, and was not

offered and did not waive counsel. Id. at 671. "When

objection to" this prior conviction (and others) "was

raised up on direct appeal, the Court of Criminal

Appeals of Texas refused to consider the challenges

because no objection to them had been made at trial."

Id. at 670. The Supreme Court granted certiorari and

remanded to this court "for further consideration in

light of Wainwright v. Sykes." Estelle v. McDonald,

433 U.S. 904 , 97 S.Ct. 2967, 53 L.Ed.2d 1088 (1977).

On remand, we noted that evidence

of the prior invalid and uncounseled Arkansas

conviction "was not objected to" at defendant's

Texas trial "as required by the Texas

contemporaneous objection rule" and that accordingly

"[u]nder Sykes, petitioner is precluded from

obtaining federal habeas relief due to his

procedural default unless he can establish cause for

failing to object." McDonald v. Estelle, 564 F.2d

199, 200 (5th Cir.1977). We accordingly remanded to

the district court "for the limited purpose of

providing petitioner the opportunity to demonstrate

cause for noncompliance with the Texas

contemporaneous objection rule." Id. at 200.

In Loud v. Estelle, 556 F.2d 1326

(5th Cir.1977), we rejected a habeas attack on a

1970 Texas conviction and life sentence as enhanced

by two prior convictions, one of which petitioner

asserted resulted when in 1960 his originally

probated 1959 sentence was revoked "without a

hearing, without counsel, and without petitioner's

knowledge or presence," which he claimed was

constitutionally required by Mempa v. Rhay, 389 U.S.

128, 88 S.Ct. 254, 19 L.Ed.2d 336 (1967). Loud at

1327-28.

We held that under Wainwright v.

Sykes "all attacks on the constitutionality of the

1960 revocation hearing are foreclosed by the

petitioner's failure to object to the admission of

the conviction at the punishment phase of his trial"

and that "[a]fter Wainwright v. Sykes, petitioner

has waived any objections he might have had to use

of the 1959 conviction to enhance his sentence."

Loud at 1329, 1330. In Nichols v. Estelle, 556 F.2d

1330 (5th Cir.1977), cert. denied, 434 U.S.

1020 , 98 S.Ct. 744, 54 L.Ed.2d 767 (1978),

we denied habeas relief as to a 1973 Texas

conviction and life sentence under the Texas

habitual offender statute based on a 1965 Oklahoma

conviction which the petitioner claimed was void

because, inter alia, he was denied counsel on

appeal, stating "But petitioner's counsel failed to

object to the admission of the Oklahoma conviction

on the ground that counsel had not been provided on

appeal. This failure worked a waiver of the

constitutional error complained of here." Id. at

1331 (footnote omitted) (citing Wainwright v. Sykes

and Loud ).

Our decision in Weaver v.

McKaskle, 733 F.2d 1103 (5th Cir.1984), is likewise

controlling. There we rejected Weaver's federal

habeas challenge to his 1977 Texas robbery

conviction and life sentence at the punishment phase

of which evidence was introduced of Weaver's 1960

Illinois conviction. At trial, Weaver objected to

the Illinois conviction only on the ground that it

was not final, as he had been pardoned. In 1980, an

Illinois court set aside the 1960 conviction because

at the 1960 trial there existed a bona fide question

as to Weaver's competency to stand trial, and no

hearing had been held to determine his competence as

required by Pate v. Robinson, 383 U.S. 375, 86 S.Ct.

836, 15 L.Ed.2d 815 (1966). Weaver at 1104. We held

that the constitutional invalidity of the 1960

Illinois conviction did not entitle Weaver to habeas

relief because of his failure to object at the 1977

trial to the 1960 conviction on that basis as

required by the Texas contemporaneous objection rule,

invoking Wainwright v. Sykes and Engle v. Isaac, 456

U.S. 107, 102 S.Ct. 1558, 71 L.Ed.2d 783 (1982).

We explained: "Under Texas law, a

defendant's failure to object at trial to the

introduction of an allegedly infirm prior conviction

precludes a later attack upon the conviction that

utilized the prior conviction.... Even where the

alleged error is of constitution dimension," id.,

and "Texas courts ... have barred a subsequent

attack on a conviction in which the sentence was

enhanced through use of an uncounseled and void

prior conviction where the defendant failed to

object." Id. at 1107.

More recently, in Smith v.

Collins, 977 F.2d 951 (5th Cir.1992), cert. denied,

510 U.S. 829 , 114 S.Ct. 97, 126 L.Ed.2d 64 (1993),

the federal habeas petitioner challenged his 1977

Texas conviction and life sentence on the basis that

at the punishment stage of that trial evidence was

introduced of his 1952 conviction which was

subsequently (in 1985) set aside on the basis of a

Turner v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 466, 85 S.Ct. 546, 13

L.Ed.2d 424 (1965), violation. We held that this

challenge was barred under Wainwright v. Sykes and

its progeny by the petitioner's failure to object at

his 1977 trial to the introduction there of evidence

of the 1952 conviction, as required by the Texas

contemporaneous objection rule.

Hogue's argument that Texas'

contemporaneous objection rule is or was not

regularly followed in respect to invalid prior

convictions is necessarily foreclosed by our

decisions in Loud (1970 Texas trial; invalid prior

Texas conviction); Nichols (1973 Texas trial;

invalid prior Oklahoma conviction); McDonald (1973

Texas trial; invalid prior Arkansas conviction);

Weaver (1977 Texas trial; invalid prior Illinois

conviction); Smith (1977 Texas trial; invalid prior

Texas conviction). One panel of this Court may not

overrule another (absent an intervening decision to

the contrary by the Supreme Court or the en banc

court, of which there are none). But even if we were

free to do so, we see no valid basis to depart from

those decisions. They are well supported not only by

the long established general principles of the Texas

contemporaneous objection rule, but also by many

decisions of the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals

applying that rule in the specific context of

failure to object to evidence of a prior invalid

conviction, as reflected by the above cited cases of

Gill, Wright, Sanders, Reed, Hill, Ridley, and

Cashman.

Only one of the cases relied on

by Hogue can be said to be in point, as the others

all involve either a recognized exception to the

Texas contemporaneous objection rule plainly not

applicable here or are otherwise simply inapposite.

This single case is Smith v. State, 486 S.W.2d 374 (Tex.Crim.App.1972).

That was a direct appeal from a felony shoplifting

conviction where a life sentence was imposed by

reason of enhancement by two prior felonies alleged

in the indictment. At the punishment stage the

defendant pleaded guilty to the enhancement

allegations. While the appeal was pending, the

defendant caused one of the prior convictions to be

set aside because the defendant was without counsel,

and the Court of Criminal Appeals, in the direct

appeal, accordingly modified the sentence to ten

years (enhanced by only one valid prior conviction).

The opinion does not discuss the

failure to object or even mention the

contemporaneous objection rule. Smith v. State was

expressly overruled en banc in Hill. Hogue argues

that comes too late, for Hill was not decided until

1982, and he was tried in 1980. However, Smith v.

State (a 1972 decision) had been effectively

abandoned long before then. Ex parte Gill was

decided in 1974, and applied the contemporaneous

objection rule to an invalid prior conviction

introduced at a 1970 trial; Wright was likewise

handed down in 1974 and applied the contemporaneous

objection rule to an invalid prior conviction

introduced at a 1973 trial; so also with Sanders, a

1979 en banc decision; Reed, a 1981 en banc decision

applicable to a 1972 trial; Ridley, a 1983 en banc

decision applicable to a 1977 trial; and Cashman, a

1983 en banc decision applicable to a 1977 trial.

Hill itself was applicable to a trial well prior to

October 1981.

And, our decisions in Loud (1977), Nichols (1977),

and McDonald (1977) apply the Texas contemporaneous

objection rule to the failure to object to evidence

of an invalid prior conviction and were all handed

down years after Smith v. State and years before

Hogue's 1980 trial, while in Weaver and Smith v.

Collins we applied the Texas contemporaneous

objection rule to 1977 trials.

Further, all these decisions,

both of the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals and of

our court (except Smith v. Collins), were handed

down years before the Court of Criminal Appeals

affirmed Hogue's conviction on direct appeal.

Finally, as Hill points out, Smith v. State was

inconsistent with prior Texas decisions and the then

long established Texas contemporaneous objection

rule. Smith v. State cannot sustain the weight Hogue

would place on it. This single 1972 decision does

not rise even to the level of "the relatively few

occasions" of disregard of the rule which Amos held

were not sufficient to defeat the required

regularity of application. Id., 61 F.3d at 345. It

is clear that Texas courts do and did apply the

contemporaneous objection rule in at least "the vast

majority" of claims similar to Hogue's. Amos at 389.

We reject Hogue's contention to the contrary.

Hogue's third and final argument

against applying the procedural bar of failure to

comply with the Texas contemporaneous rule is that

no Texas court expressly denied his complaint

concerning the admission at the sentencing phase of

the allegedly invalid Colorado conviction on that

basis. In this connection, Hogue invokes the

principle of Harris v. Reed, 489 U.S. 255, 109 S.Ct.

1038, 103 L.Ed.2d 308 (1989), that "a procedural

default does not bar consideration of a federal

claim on either direct or habeas review unless the

last state court rendering a judgment in the case '

"clearly and expressly" ' states that its judgment

rests on a state procedural bar." Id. at 263, 109

S.Ct. at 1043.

However, this rule of Harris "applies

only when it fairly appears that a state court

judgment rested primarily on federal law or was

interwoven with federal law." Coleman v. Thompson,

501 U.S. 722 , 739, 111 S.Ct. 2546, 2559, 115 L.Ed.2d

640 (1991). As we recognized in Young v.

Herring, 938 F.2d 543 (5th Cir.1991) (en banc), in

Coleman "[t]he Court explicitly rejected Coleman's

contention that the Harris rule should apply

whenever the state court decision does not contain a