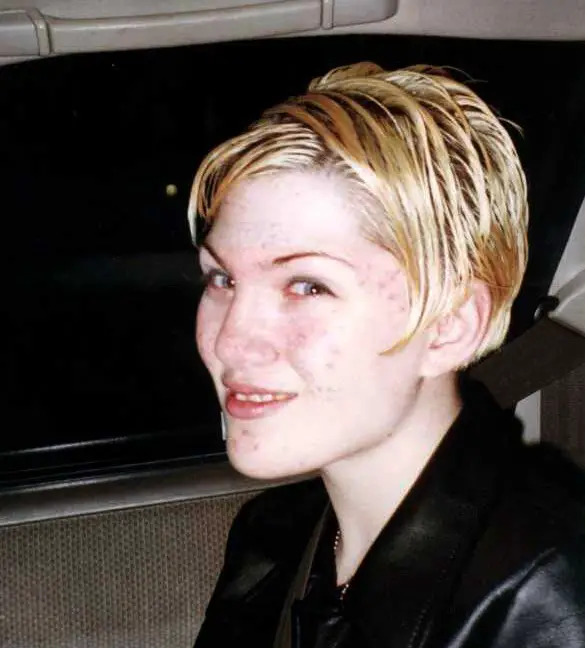

WASHINGTON COUNTY - - Martin Allen Johnson,

suspect in the homicide of 15 year old Heather Fay Fraser, was arrested

in the Orlando, Florida area by US Marshals after receiving a tip via

the television program, America’s Most Wanted.

Just over a year ago, on February 23, 1998, 15 year

old Heather Fraser’s disappeared. Her body was found and recovered in

the Columbia River near Warrenton, Oregon on the following day.

Martin Johnson was quickly developed as a "person of

interest" and eventually a suspect. Attempts to locate Johnson over the

past year, however, proved fruitless. Sheriff’s Detectives recently came

in contact with producers of the internationally recognized crime show,

America’s Most Wanted (AMW). AMW agreed to air the story

yesterday, February 20, 1999.

Almost immediately after the show aired on the East

Coast, a tip came into the AMW hotline suggesting that Johnson was

living in the Orlando area. US Marshals from Portland, and local

Marshals from the Orlando, established a surveillance of the location

provided by the tipster. Johnson was soon arrested by the federal agents

and taken into their custody.

Johnson is currently being held on the sole federal

charge of Unlawful Flight to Avoid Prosecution. He has not yet been

charged with sexual assault warrants that exist in Clackamas and

Multnomah Counties. Grand Jury regarding the Fraser homicide is

scheduled in Washington County the first week on March.

FILED: April 28, 2004

IN THE COURT OF APPEALS OF THE STATE OF

OREGON

STATE OF OREGON, Respondent,

v.

MARTIN ALLEN JOHNSON, Appellant.

9800590; A116313

Appeal from Circuit Court, Clackamas County.

Raymond R. Bagley, Judge.

Argued and submitted January 29, 2004.

Susan F. Drake, Deputy Public Defender, argued the

cause for appellant. On the brief were David E. Groom, Acting Executive

Director, Office of Public Defense Services, and Mary M. Reese, Senior

Deputy Public Defender.

Martin Allen Johnson filed the pro se

supplemental appellant's brief.

Paul L. Smith, Assistant Attorney General, argued the

cause for respondent. With him on the brief were Hardy Myers, Attorney

General, and Mary H. Williams, Solicitor General.

Before Haselton, Presiding Judge, and Linder and

Ortega, Judges.

LINDER, J.

Reversed and remanded with instructions to dismiss

without prejudice.

LINDER, J.

Defendant appeals a judgment of conviction for rape

in the third degree, ORS 163.355, challenging the trial court's denial

of his motion to dismiss on speedy trial grounds. We conclude that the

motion should have been granted under ORS 135.747, because defendant

neither caused nor consented to the delay in his prosecution and because

the length of the delay was unreasonable. Accordingly, we reverse and

remand for entry of judgment of dismissal without prejudice.

The pertinent facts are procedural. Early in 1998,

defendant became a "person of interest" in a homicide investigation in

Washington County, and he fled the state after his home was searched in

connection with that investigation. In the course of the homicide

investigation, police discovered information that led them to a minor

female who disclosed that she had had sexual intercourse with defendant

in Clackamas County in 1997.

As a result of that disclosure, a Clackamas County

grand jury indicted defendant in April 1998 on one count of rape in the

third degree and two counts of sexual abuse in the third degree. A

warrant for defendant's arrest issued a few days later but was not

served because defendant was no longer in the state. Meanwhile,

defendant was indicted in Washington County on an unrelated charge of

aggravated murder.

Months passed. To be precise, more than 20 months

passed from the date of defendant's return to Oregon without Clackamas

County taking any action to pursue the charges pending against defendant

in that county. Then, according to defendant, in November 2000 he

learned inadvertently from Washington County jail officials that

Clackamas County had placed a hold on him, which in turn caused him to

learn of the Clackamas County charges. Defendant requested a speedy

trial on the Clackamas County charges. In response, on December 20,

2000, defendant was served with an arrest warrant on the Clackamas

County charges and arraigned the following day.

Trial on the Clackamas County charges initially was

scheduled for February 9, 2001. The date was postponed several times, on

defendant's motion or that of his attorney (during times that defendant

was represented). Defendant waived his speedy trial rights for purposes

of any postponements that occurred after the scheduled trial date. But

he preserved them--and the trial court understood him to do so--as to

the state's delay in bringing his case to trial between the time that he

was returned to Oregon custody and the time that Clackamas County served

its arrest warrant and arraigned him. Eventually, defendant moved to

dismiss the Clackamas County charges on both constitutional and

statutory speedy trial grounds.

The trial court denied the motion, concluding that

the delay between indictment and service of the warrant was "attributable

to the defendant's absence from the State of Oregon." The trial court

further concluded that, once defendant was returned to Oregon and

requested a speedy trial, he was promptly "served with the arrest

warrant and arraigned." Further delays in defendant's prosecution were "at

the request of the defendant in order to prepare the case."

On appeal, defendant challenges only the trial

court's ruling on his statutory right to speedy trial. Defendant points

out that approximately three years and five months elapsed between his

indictment and trial.

Defendant acknowledges, however, that not all of that

delay is attributable to the state. In particular, he agrees that the

state could not serve the arrest warrant because he had absconded and

that the state's first opportunity to do so came when defendant was

brought to Oregon from Florida and lodged in the Washington County jail.

Defendant also agrees that the postponements of his

trial at his request are not attributable to the state. Defendant

asserts, however, that the delay in the prosecution of his case for more

than 20 months "while he sat in the Washington County jail awaiting

trial on aggravated murder" is attributable entirely to the state and

violated ORS 135.747.

In response, the state argues that defendant

impliedly consented to that delay by "elect[ing] to wait 20 months"

before requesting a speedy trial on the Clackamas County charges, and

that the delay was reasonable because it was appropriate for the state

to proceed to trial first on the most serious charge against defendant (i.e.,

the aggravated murder charge in Washington County).

ORS 135.747 provides:

"If a defendant charged with a crime, whose trial

has not been postponed upon the application of the defendant or by

the consent of the defendant, is not brought to trial within a

reasonable period of time, the court shall order the accusatory

instrument to be dismissed."

The statute applies to delays between indictment and

arrest. State v. Rohlfing, 155 Or App 127, 130, 963 P2d 87

(1998). A defendant is entitled to dismissal under the statute if the

defendant did not cause or consent to the delay and if the case has not

been brought to trial within a reasonable period of time. State v.

Emery, 318 Or 460, 470-71, 869 P2d 859 (1994); State v. Green,

140 Or App 308, 310-11, 915 P2d 460 (1996). Whether defendant was

brought to trial within a reasonable period of time is a question of law

that we review for legal error. State v. Kirsch, 162 Or App 392,

394-95, 987 P2d 556 (1999).

We turn to the first prong of the statutory inquiry:

whether defendant consented to or caused the delay. Although the state

acknowledges that defendant did not expressly consent to the pertinent

delay in his prosecution, it argues that he impliedly did so.

Specifically, the state argues that defendant knew about the Clackamas

County charges while he was awaiting trial in Washington County and that

he impliedly consented to the delay by doing "nothing to notify the

state or the court of his desire to proceed to trial on those charges."

There are two problems with the

state's argument. The first is that the record does not establish the

factual predicate for it. The state presented no evidence that defendant

knew of the Clackamas County charges. In that regard, the state argues

that the charges "would have been readily apparent to defendant almost

as soon as he arrived in Oregon." But the state provides no support or

further explanation for that argument, and we fail to see why it would

be necessarily so. Likewise, contrary to the state's position, there is

no basis on this record to infer that defendant necessarily or likely

knew that Clackamas County had placed a "hold" on him. Consequently, the

mere existence of the hold, without more, permits only speculation as to

whether defendant was aware of the Clackamas County charges.

The second problem with the state's argument is that,

as a legal matter, implied consent does not arise from the mere failure

on a defendant's part to insist that the state bring a case to trial.

That is true regardless of the defendant's awareness of the charges

against him or her. For example, in Emery, the defendant knew of

the charge against him and appeared for trial on the scheduled date,

apparently unaware that the trial judge had removed himself from the

case due to a conflict of interest. When the trial did not take place as

scheduled, the defendant and the state unsuccessfully engaged in plea

negotiations. Beyond that, the state made no effort to bring the

defendant to trial until more than two years had elapsed, and the

defendant did nothing during that time to demand a speedy trial.

Emery, 318 Or at 462-63. The Supreme Court concluded that the delay

was not attributable to the defendant's consent. Id. at 471.

See also Rohlfing, 155 Or App at 131 (the defendant did not

impliedly consent to delay where he was unaware of the indictment and

did not move or leave the state to avoid arrest). In other words, it

remains true that "[t]he law imposes no duty on a defendant, charged

with a crime, of calling his case for trial or insisting that it be set

for trial at any particular time. That duty devolves upon the state."

State v. Chadwick, 150 Or 645, 650, 47 P2d 232 (1935), overruled

in part on other grounds, State v. Crosby, 217 Or 393, 342

P2d 831 (1959).

The remaining question is whether the delay was

reasonable considering all of the circumstances. Factors to be

considered in determining the reasonableness of the delay include the

nature of the charges, the length of the delay, and the state's

explanation--or lack of one--for failing to bring the case to trial.

State v. Davids, ___ Or App ___, ___, ___ P3d ___ (Apr 28, 2004)

(slip op at 8). In general, when a defendant has not consented to the

delay and the state does not offer an explanation for it, delays of 15

months or more are unreasonable. Id. at ___ (slip op at 7-8 n 4)

(surveying cases).

Here, at the hearing on defendant's motion to

suppress, the state offered no explanation for its failure to take any

steps whatsoever to bring defendant's case to trial in Clackamas County.

Tellingly, once defendant requested a speedy trial, the state responded

within less than a month by serving the outstanding arrest warrant on

defendant and arraigning him the next day. Those facts suggest that the

delay was due to neglect, oversight, or lack of interest.

On appeal, the state argues for the

first time that the delay was reasonable because it was "in defendant's

best interests." More specifically, the state argues that the delay

benefitted defendant by allowing him to defend the aggravated murder

charge in Washington County without distraction. The first problem with

that argument is that it was not advanced below and, consequently, the

record is undeveloped in that regard. In particular, nothing in the

factual record establishes that the Clackamas County prosecutor delayed

serving defendant with the arrest warrant and bringing him to trial for

that reason. Second, and in all events, defendant's speedy trial right

was his to waive, not the state's.

In sum, defendant neither caused nor consented to the

unexplained delay in the prosecution of the Clackamas County charges.

Those facts, coupled with the length of that delay--more than 20 months--render

the delay unreasonable. We therefore conclude that defendant's motion to

dismiss on statutory speedy trial grounds should have been granted.

Reversed and remanded with instructions to dismiss

without prejudice.