In The Court of Criminal Appeals of Texas

AP-75,050

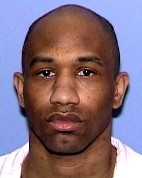

Elijah Dwayne Joubert, Appellant

v.

The State of Texas

ON DIRECT APPEAL FROM

HARRIS COUNTY

CAUSE NO.

944756 IN THE 351ST JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT

Per curiam.

The appellant was convicted in

October 2004 of capital murder. (1)

Based on the jury's answers to the special issues set forth in

Code of Criminal Procedure Article 37.071, sections 2(b) and 2(e),

the trial judge sentenced the appellant to death.

(2) Direct appeal to this Court is required.

(3) After reviewing the appellant's seven points of

error, we find them to be without merit. Consequently, we affirm

the trial court's judgment and sentence of death.

On April 2, 2003, Dashan Glaspie recruited his

longtime friend, the appellant, and another friend, Alfred Brown,

to help him commit robbery at a check-cashing business. Glaspie

was to act as a lookout while the appellant and Brown went inside.

They drove to the business the next morning. The owner pulled up

as the appellant and Brown were approaching. When the owner saw

them, he pulled out a handgun. The appellant and Brown returned to

the car, and the three decided to abandon the robbery because the

owner had displayed a weapon.

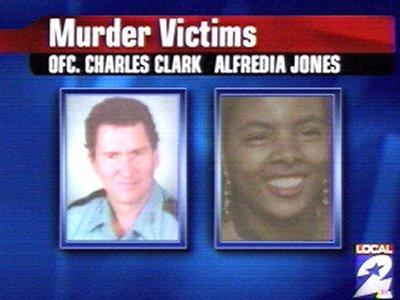

They decided to rob a different business and

drove to a second check cashing location. When Alfredia Jones

arrived to open the store, the appellant approached her at

gunpoint and walked her into the store. Shortly thereafter Glaspie

and Brown entered the store. The appellant allowed Jones to make a

phone call to another store to inform them that she was "opening

Center 24." This was actually a distress code alerting them to the

robbery. The appellant held a gun to Jones's head and told her to

open the safe, while Glaspie began checking the store for

surveillance equipment, and Brown went through Jones's purse.

Police Officer Charles Clark arrived at the scene and entered the

store. The appellant accused Jones of tipping off the police, and

he shot her. The evidence suggested that Brown shot Officer Clark.

Jones and Clark both died as a result of the gunshot wounds.

Pursuant to a thirty-year plea bargain, Glaspie testified for the

State at the appellant's trial.

In point of error four, the appellant claims

Glaspie's testimony, as accomplice-witness testimony, was not

sufficiently corroborated to support the appellant's conviction as

a principal. In his fifth point of error, he contends Glaspie's

testimony was insufficiently corroborated to support his

conviction under a parties theory. (4)

Article 38.14 provides that a conviction cannot

stand on accomplice testimony unless there is other evidence

tending to connect the defendant to the offense. The corroborating

evidence under 38.14 need not be sufficient, standing alone, to

prove beyond a reasonable doubt that a defendant committed the

offense. (5) All that is required

is that there is some non-accomplice evidence tending

to connect the defendant to the offense. Further, there is no

requirement that the non-accomplice testimony corroborate the

accused's connection to the specific element which raises the

offense from murder to capital murder. (6)

There need be only some non-accomplice evidence tending to connect

the defendant to the crime, not to every element of the crime.

(7)

Houston Police Officer James Binford testified

that he interviewed the appellant, who confessed in detail about

his involvement in the instant offense. The interview with Binford

and another officer was videotaped. The videotaped statement was

played for the jury and admitted into evidence. In the video, the

appellant admitted to participating in the instant offense, but he

denied shooting either victim. The videotaped statement was

sufficient to "tend to connect" him to the offense.

(8) The appellant's liability as a principal or under a

parties theory is of no relevance under an Article 38.14 analysis.

The question is whether some evidence "tends to connect" him to

the crime; the connection need not establish the exact nature of

his involvement (as a principal or party). The appellant's

admission that he participated in the crime, although he denied

being a shooter, is enough to tend to connect him to the offense.

Points of error four and five are overruled.

In point of error one, the appellant claims the

trial court erred in overruling his motion to dismiss the

indictment for its alleged failure to include the special

punishment issues, (9) in violation

of his right to due process of law under the Fourteenth Amendment.

The appellant contends that under Apprendi v. New Jersey,

(10) he was entitled to have the grand jury pass on the

special punishment issues before authorizing the State to proceed

on a capital murder prosecution.

Since the Supreme Court decided Apprendi

and its progeny, state courts have struggled with whether

sentencing factors, including the special punishment issues,

should be considered full-blown elements of an offense, requiring

inclusion in an indictment. (11)

Most courts, including this one, have held that the Apprendi

sentencing factors are not elements of offenses for purposes other

than the Sixth Amendment jury-trial guarantee.

(12) We have specifically rejected the argument that

Apprendi requires the State to allege the special issues in

the indictment. (13) Point of

error one is overruled.

We have not examined whether a defendant has a

right to a grand jury indictment on the special punishment issues

under the state constitution. The appellant alleges exactly this

in his second point of error. The appellant claims the trial court

erred in overruling his motion to dismiss the indictment for its

alleged failure to include the special punishment issues, in

violation of his state constitutional right to indictment by grand

jury. He contends the grand jury should be required to pass on the

special issues before the State is authorized to seek the death

penalty. The appellant misquotes King v. State

(14) to support his position, as follows:

At common law all offenses above the grade of

misdemeanor must be prosecuted by indictment, for which it was the

policy of the common law that no man should be put to death

until the necessity therefor should first be determined by a grand

jury. (15)

The appellant emphasizes that this is not a

notice issue; rather, his argument is based on the historic role

of the grand jury to serve as a check on prosecutorial power.

The actual language from King does not

support the appellant's argument. In King, while

discussing the historical basis for indictments at English common

law, the Court quoted from Corpus Juris Secundum ("C.J.S."), where

it is noted that:

At common law all offenses above the grade of

misdemeanor must be prosecuted by indictment, for it was the

policy of the common law that no man should be put on his

trial for felony, for which the punishment was death,

until the necessity therefor should first be determined by a grand

jury on oath. (16)

The appellant has reshaped the meaning of the

reference that indictments were required for all felony cases. The

point being made by the Court about the common law was that

indictments have historically served as protection against

arbitrary accusations by the government in serious criminal cases.

(17) This court has repeatedly recognized prosecutorial

discretion to seek the death penalty, and the C.J.S. excerpt in

King does nothing to change this interpretation of state

law. (18)

Further, there is nothing in the language of

the state constitution itself that requires the grand jury to pass

on special punishment issues. Article I, section 10, pertaining to

the rights of an accused in criminal cases, provides in part that

the accused "shall have the right to demand the nature and cause

of the accusation against him, and to have a copy thereof" and

that "no person shall be held to answer for a criminal offense,

unless on an indictment of a grand jury."

Article V, Section 12(b) defines an indictment:

An indictment is a written instrument presented

to a court by a grand jury charging a person with the commission

of an offense. An information is a written instrument presented to

a court by an attorney for the State charging a person with the

commission of an offense. The practice and procedures relating to

the use of indictments and informations, including their contents,

amendment, sufficiency, and requisites, are as provided by law.

The presentment of an indictment or information to a court invests

the court with jurisdiction of the cause.

Although indictments serve, in part, to "provide

the accused an impartial body which can act as a screen between

the rights of the accused and the prosecuting power of the State,"

(19) this has never been interpreted to mean that the

grand jury screening function provided in the Texas Constitution

pertains to capital sentencing issues.

In Studer v. State,

(20) this Court concluded that, after constitutional

amendments adopted in 1985, the "requisites of an indictment stem

from statutory law alone now." Articles 21.02 and 21.03 set forth

the specific requisites for an indictment, and the Court has held

that these provisions do not require the State to plead the

punishment special issues in a capital case.

(21) Point of error two is overruled.

In his third point of error, the appellant

claims the trial court erred in failing to grant his challenge for

cause against venireperson Patricia Bloom Wohlgemuth. The

appellant contends Wohlgemuth was challengeable for cause because

she would not consider any mitigating evidence during punishment.

The appellant relies on an exchange between defense counsel and

Wohlgemuth in which Wohlugemuth stated that she would not consider

several specific types of evidence named by defense counsel to be

mitigating, including: a difficult childhood, being orphaned at a

young age, drug problems, or poor schooling.

A venireperson is not challengeable for cause

on the ground that she does not consider a particular type of

evidence to be mitigating. (22)

Indeed, a party is not entitled to question a venireperson as to

whether the venireperson could consider particular types of

evidence to be mitigating. (23)

Wohlgemuth stated clearly in other portions of her voir dire that

she was open to considering mitigating evidence and would give the

mitigation issue full and careful consideration. The trial court

did not abuse its discretion in denying the appellant's challenge

for cause against Wohlgemuth. Point of error three is overruled.

In point of error six, the appellant claims the

trial court erred in granting the State's motion to prohibit him

from arguing that co-defendant Glaspie's thirty-year, plea-bargained

sentence was a mitigating factor in assessing his punishment.

Evidence was presented that Glaspie would receive a thirty-year

sentence if he testified truthfully in the appellant's trial.

Before summation at the close of the punishment phase, the court

ruled that the appellant would not be allowed to argue that

Glaspie's sentence was a mitigating circumstance in his case. The

appellant relies on Parker v. Dugger.

(24)

A co-defendant's conviction and punishment have

no bearing on a defendant's own personal moral culpability:

[E]vidence of a co-defendant's conviction and

punishment is not included among the mitigating circumstances

which a defendant has a right to present. In Evans v. State,

656 S.W.2d 65, 67 (Tex.Crim.App.1983), we stated:

"We do not see how the conviction and

punishment of a co-defendant could mitigate appellant's

culpability in the crime. Each defendant should be judged by his

own conduct and participation and by his own circumstances."

(25)

The appellant's reliance on Parker is

misplaced. In Parker, the United States Supreme Court

recognized that evidence of the co-defendants' sentences was part

of the mitigating evidence admitted at Parker's trial. But this

evidence was admissible under Florida law.

(26) The Supreme Court in Parker recognized

that this evidence was presented as mitigating evidence under

Florida law; it did not address whether exclusion of such evidence

would be a violation of federal law or otherwise address any

rationale for inclusion of such evidence under federal law.

(27) This Court has rejected the argument that

Parker compels consideration of punishments received by co-defendants,

concluding that such punishments "relate[] neither to appellant's

character, nor to his record, nor to the circumstances of the

offense." (28) Point of error six

is overruled.

In his seventh point of error, the appellant

claims the trial court erred by instructing the jury that it could

answer special issue two, "Yes," if they found that the appellant

had merely anticipated that a death would occur during the

underlying robbery, in violation of his right against cruel and

unusual punishment. He contends the issue permitted a finding in

favor of the death penalty without a finding that he intended that

a killing occur. He relies on Enmund v. Florida,

(29) and Tison v. Arizona.

(30) This argument has been rejected in other cases,

(31) and we are not persuaded to overrule that precedent.

Point of error seven is overruled.

The judgment of the trial court is affirmed.

Delivered: October 3, 2007.

Publish.

*****

1. Penal Code � 19.03(a).

2. Art. 37.071 � 2(g).

Unless otherwise indicated, all references to Articles refer to

the Code of Criminal Procedure.

3. Art. 37.071 � 2(h).

4. The indictment alleged

the appellant committed capital murder in either of two ways: (1)

by causing the death of Jones during the course of committing a

robbery of Jones; or (2) by causing the deaths of Jones and Clark

during the same criminal transaction. The jury was authorized to

convict the appellant under either paragraph, either as a

principal or under the law of parties.

5. Vasquez v. State,

67 S.W.3d 229, 236 (Tex. Crim. App. 2002).

6. Vasquez v. State,

56 S.W.3d 46, 48 (Tex. Crim. App. 2001).

7. Id.

8. See Jackson

v. State, 516 S.W.2d 167, 171 (Tex. Crim. App. 1974) (stating

that defendant's admission or confession is, under most

circumstances, sufficient to corroborate accomplice testimony).

9. Pursuant to Article

37.071, upon a finding of capital murder, these questions must be

submitted to the jury if the State seeks the death penalty:

(1) whether there is a probability that the

defendant would commit criminal acts of violence that would

constitute a continuing threat to society; and

(2) in cases in which the jury charge at the

guilt or innocence stage permitted the jury to find the defendant

guilty as a party under Sections 7.01 and 7.02, Penal Code,

whether the defendant actually caused the death of the deceased or

did not actually cause the death of the deceased but intended to

kill the deceased or another or anticipated that a human life

would be taken.

(c) The state must prove each issue submitted

under Subsection (b) of this article beyond a reasonable doubt,

and the jury shall return a special verdict of "yes" or "no" on

each issue submitted under Subsection (b) of this Article.

10. 530 U.S. 466 (2000).

11. Kevin R. Reitz,

Symposium: Sentencing: What's at Stake for States? Panel Two:

Considerations at Sentencing- What Factors are Relevant and Who

Should Decide? The New Sentencing Conundrum: Policy and

Constitutional Law at Cross-Purposes, 105 Colum. L. Rev.

1082, 1093, note 42 (2005).

12. Id., at note

42.

13. See Renteria v.

State, 206 S.W.3d 689, 709 (Tex. Crim. App. 2006) (citing

Russeau v. State, 171 S.W.3d 871, 886 (Tex. Crim. App. 2005),

cert. denied, 126S. Ct. 2982 (2006), (Apprendi

and Ring have no applicability to Article 37.071);

Rayford v. State, 125 S.W.3d 521, 533 (Tex. Crim. App.

2003)).

14. 473 S.W.2d 43, 45 (Tex.

Crim. App. 1971).

15. Id. (alteration

in original).

16. Id. (emphasis

added).

17. Id.

18. Cf. Russeau,

171 S.W.3d, at 887 (State's discretion to seek death penalty is

not unconstitutional, citing Hankins v. State, 132 S.W.3d

380, 387 (Tex. Crim. App. 2004), and Ladd v. State, 3 S.W.3d

547, 574 (Tex. Crim. App.1999)).

19. Teal v. State,

230 S.W.3d 172, 175 (Tex. Crim. App. 2007).

20. 799 S.W.2d 263, 272 (Tex.

Crim. App. 1990).

21. Rosales v. State,

748 S.W.2d 451, 458 (Tex. Crim. App. 1987); Sharp v. State,

707 S.W.2d 611, 624 (Tex. Crim. App. 1986).

22. Standefer v. State,

59 S.W.3d 177, 181-82 (Tex. Crim. App. 2001); Rosales v. State,

4 S.W.3d 228, 233 (Tex. Crim. App. 1999); Raby v. State,

970 S.W.2d 1, 3 (Tex. Crim. App. 1998).

23. Rosales, 4 S.W.3d,

at 233.

24. 498 U.S. 308 (1991).

25. Morris v. State,

940 S.W.2d 610, 613 (Tex. Crim. App. 1996).

26. See Boldender v.

Singletary, 16 F.3d 1547, 1566 n.27 (11th Cir. 1994) (noting

that under Florida law, disparate treatment of co-defendants can

constitute non-statutory mitigating circumstance where defendants

are equally culpable).

27. See Morris,

940 S.W.2d at 613 (observing that the Court in Parker did

not address whether evidence of disparate sentencing is mitigating

evidence which must be considered under Lockett v. Ohio,

438 U.S. 586 (1978)); see also State v. Ward, 449 S.E.2d

709, 737 (N.C. 1994)("It did not address . . .or otherwise suggest

that the exclusion of such evidence was improper as a matter of

federal law.").

28. Morris, 940

S.W.2d, at 613.

29. 458 U.S. 782 (1982).

30. 481 U.S. 137 (1987).

31. Ladd, 3 S.W.3d,

at 573; Cantu v. State, 939 S.W.2d 627, 644-45 (Tex. Crim.

App. 1997).