Jackson v. Commonwealth, 266 Va. 423, 587

S.E.2d 532 (Va. 2003) (Direct Appeal).

Defendant was convicted in the Circuit Court, City of

Newport News, Verbena M. Askew, J., of, among other things, capital

murder, and received death penalty sentence on basis of aggravating

factor of vileness. Defendant appealed from his capital murder

conviction and from his non-capital convictions, and those appeals were

consolidated with the automatic review of his death sentence. The

Supreme Court, Elizabeth B. Lacy, J., held that: (1) evidence was

insufficient that defendant's confession was involuntary; (2) defendant

was not entitled to poll jury as to which statutory element(s)

established vileness; (3) commonwealth gave sufficient race-neutral

justifications for exercising all of its five peremptory challenges

against African-Americans; (4) trial court acted within its discretion

in allowing commonwealth to cross-examine defendant's DNA expert

regarding his refusal to meet with commonwealth's DNA expert; (5) trial

court properly barred defendant from asking his expert witness a line of

questions regarding veracity of defendant's confession based on

transference theory; (6) lack of forensic evidence connecting defendant

to crime scene, other that DNA testing results which involved only eight

loci, six of which were matched by defendant's DNA, did not support

conclusion that evidence was insufficient to prove defendant's guilt;

and (7) death sentence was neither excessive nor disproportionate to

penalty imposed in similar cases. Affirmed.

OPINION BY Justice ELIZABETH B. LACY.

In this appeal, we review the capital murder

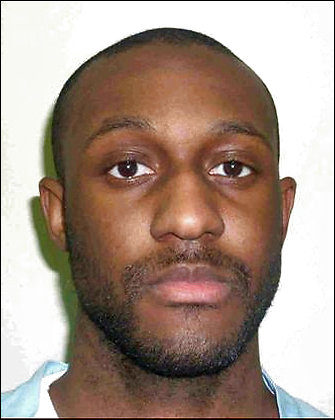

conviction and death penalty imposed on Kent Jermaine Jackson, along

with his convictions of robbery, felony stabbing, and statutory burglary.

FACTS

In accord with established principles of appellate

review, we recite the facts in the light most favorable to the

Commonwealth, the party prevailing below. Commonwealth v. Bower, 264 Va.

41, 43, 563 S.E.2d 736, 737 (2002).

On April 18, 2000, the body of Beulah Mae Kaiser, 79

years of age, was found in her apartment. According to the medical

examiner, Mrs. Kaiser died from a combination of a stab wound to her

jugular vein, a fractured skull, and asphyxia caused by blockage of her

airway by her tongue. Any one of these injuries could have been fatal.

In addition to these injuries, Mrs. Kaiser suffered

two black eyes, a broken nose, and multiple abrasions, lacerations, and

bruises. She had five stab wounds to her head and neck, including the

wound to her jugular vein.

The medical examiner also testified that Mrs. Kaiser

had been anally sodomized with her walking cane and that the cane then

had been driven into her mouth with such violence that it knocked out

most of her teeth, tore her tongue and forced it into her airway,

fractured her jaw, and penetrated the left side of her face.

When Mrs. Kaiser's body was found, her apartment was

in disarray. Personal items were strewn throughout the apartment, blood

spatters were on the surfaces of the apartment, and the contents of Mrs.

Kaiser's purse had been dumped on the floor. The police were unable,

however, to find a weapon or any fingerprints of value.

The crime went unsolved for over 16 months until DNA

testing of saliva on a cigarette butt found in the apartment implicated

an individual named Cary Gaskins.

An interview with Gaskins led the police to Joseph M.

Dorsett and Jackson, who had been roommates in an apartment across the

hall from Mrs. Kaiser's apartment at the time of her death. Following an

interview with Dorsett, Newport News police arrested Dorsett, charging

him with Mrs. Kaiser's murder, and obtained a warrant for Jackson's

arrest.

Police arrested Jackson at a girlfriend's home in

King George County around 4:00 a.m. on August 29, 2001. During an

interview with Newport News police detectives at the King George County

jail that afternoon, Jackson confessed to the murder of Mrs. Kaiser.

PROCEEDINGS

On January 14, 2002, Jackson was indicted by a

Newport News grand jury for the capital murder of Beulah Mae Kaiser in

the commission of a robbery or attempted robbery, robbery, felony

stabbing,statutory burglary, and object sexual penetration, in violation

of Code §§ 18.2-31, 18.2-58, 18.2-53, 18.2-90, and 18.2-67.2,

respectively.

Prior to trial, Jackson filed motions seeking a

change of venue, suppression of his confession, a bill of particulars,

and additional peremptory strikes. The trial court denied these motions

and rejected Jackson's arguments that Virginia's capital murder statutes

are unconstitutional. Following a six-day trial, a jury convicted

Jackson of all charges except object sexual penetration.

In a subsequent sentencing proceeding, the jury found

the aggravating factor of vileness and fixed a sentence of death for the

capital murder conviction and fixed sentences totaling life imprisonment

plus 25 years and a $100,000 fine for the remaining convictions. During

a post-verdict hearing, the trial court considered the pre-sentence

report, further evidence presented by Jackson, and the arguments of

counsel. In its final judgment, the trial court imposed the sentences

fixed by the jury.

We have consolidated the automatic review of

Jackson's death sentence with his appeal of the capital murder

conviction in Record No. 030749 and have given them priority on the

docket. Code §§ 17.1-313(A), (F), and (G). We have also certified

Jackson's appeal of his non-capital convictions from the Court of

Appeals of Virginia, Record No. 030750, and have consolidated the two

records for consideration.

ISSUES PREVIOUSLY DECIDED

Jackson raises fifteen assignments of error, four of

which contain arguments that this Court has rejected in previous cases.

Since Jackson presents no new arguments on these questions, we adhere to

our previous holdings and affirm the rulings of the trial court:

(1) denying the defendant's motion for a bill of

particulars seeking a narrowing construction of the vileness aggravator

and identification of the evidence on which the Commonwealth intended to

rely when seeking the death penalty. See Green v. Commonwealth, 266 Va.

81, 107, 580 S.E.2d 834, 849 (2003); Goins v. Commonwealth, 251 Va. 442,

454, 470 S.E.2d 114, 123 (1996); Strickler v. Commonwealth, 241 Va. 482,

490, 404 S.E.2d 227, 233 (1991).

(2) refusing to declare Virginia's capital murder

statutes unconstitutional because (a) they do not adequately instruct

the jury on the weight it should assign to aggravating and mitigating

factors,Satcher v. Commonwealth, 244 Va. 220, 228, 421 S.E.2d 821, 826

(1992), (b) do not require aggravating factors to outweigh mitigating

factors beyond a reasonable doubt, Mickens v. Commonwealth, 247 Va. 395,

403, 442 S.E.2d 678, 684 (1994), vacated and remanded on other grounds,

513 U.S. 922, 115 S.Ct. 307, 130 L.Ed.2d 271 (1994); (c) are

unconstitutionally vague in defining “vileness” and “future

dangerousness,” Id.; (d) allow evidence of unadjudicated criminal

conduct in the sentencing phase, Satcher, 244 Va. at 228, 421 S.E.2d at

826; (e) constitute cruel and unusual punishment, Spencer v.

Commonwealth, 238 Va. 275, 280-81, 384 S.E.2d 775, 777-78 (1989), and

are contrary to “evolving standards of decency” under Trop v. Dulles,

356 U.S. 86, 100, 78 S.Ct. 590, 2 L.Ed.2d 630 (1958), Satcher, 244 Va.

at 228, 421 S.E.2d at 826; (f) do not require the court to set aside the

death penalty on showing of good cause, Breard v. Commonwealth, 248 Va.

68, 76, 445 S.E.2d 670, 675-76 (1994); (g) allow the court to consider

hearsay evidence in its post-sentencing report, O'Dell v. Commonwealth,

234 Va. 672, 701-02, 364 S.E.2d 491, 507-08 (1988); and (h) fail to

provide meaningful appellate review, Satcher, 244 Va. at 228, 421 S.E.2d

at 826. See generally Breard, 248 Va. at 75-76, 445 S.E.2d at 675.

(3) denying the defendant's motion for additional

peremptory challenges. See Green, 266 Va. at 107, 580 S.E.2d at 849;

Spencer, 240 Va. at 84, 393 S.E.2d at 613; Buchanan v. Commonwealth, 238

Va. 389, 405, 384 S.E.2d 757, 767 (1989); O'Dell, 234 Va. at 690, 364

S.E.2d at 501.

(4) refusing the defendant's request to use a juror

questionnaire. See Green, 266 Va. at 95-96, 580 S.E.2d at 842-43;

Strickler, 241 Va. at 492-93, 404 S.E.2d at 234.

ISSUES NOT PRESERVED

A. Change of Venue

Jackson, in his second assignment of error, charges

that the trial court erroneously denied his motion for change of venue.

The Commonwealth argues that Jackson has waived this assignment of error

because he neither renewed the motion at the time the jury was selected

nor objected to the seating of the panel.

In Green, we stated that when a change of venue

motion is taken under advisement or continued until the jury is

empaneled, it is incumbent on the party seeking a change of venue to

renew the motion or otherwise bring it to the court's attention. Green,

266 Va. at 94-95, 580 S.E.2d at 842. Failure to do so implies

acquiescence in the jury panel and is tantamount to waiver of the motion

for change of venue. Id.

In this case, the trial court denied Jackson's motion

for a change of venue in a pre-trial hearing but stated that the motion

was “a continuing motion as we go through this process.” Jackson did not

seek a ruling on this “continuing motion,” did not bring the matter to

the trial court's attention, and made no objection based on venue before

the trial court empaneled the jury. Accordingly, Jackson has waived this

assignment of error, and we will not address his claims that the trial

court erred by refusing to grant his motion for a change of venue. Id.;

Rule 5:25.

B. Admission of Photographs

Jackson's eighth assignment of error challenges the

trial court's refusal to limit the presentation of crime scene and

autopsy photographs of the decedent. Jackson argues here that the

gruesome content of the photographs served merely to shock and inflame

the jury, and, because Jackson had stipulated to an autopsy report and

diagrams indicating the manner of Mrs. Kaiser's death, the fourteen

photographs introduced by the Commonwealth were cumulative and had no

probative value. The Commonwealth argues that Jackson has waived this

claim because he did not object to the admission of the photographs at

trial.

In a pre-trial motion, Jackson sought to limit the

number of photographs depicting the condition of the decedent that could

be introduced at trial, arguing that the photographs were cumulative.

The trial court agreed that it would not admit cumulative evidence but

denied Jackson's motion as premature because the Commonwealth had not

yet determined which photographs it would introduce at trial. When the

Commonwealth introduced all fourteen photographs as evidence, Jackson

did not object. Jackson's failure to renew his objection at that time

precludes him from raising this issue on appeal. Rule 5:25.

C. Trial Court's Proportionality Review

Jackson asserts that the trial court erred in not

examining whether the jury's verdict imposing the penalty of death was

based on passion or prejudice and whether the punishment was

disproportionate in this case pursuant to Code § 17.1-313. While we note

that Code § 17.1-313 does not require such a review by the trial court,

Green, 266 Va. at 107, 580 S.E.2d at 849, Jackson neither asked the

trial court to conduct such a review nor addressed such review by the

trial court on brief or in oral argument in this Court. Accordingly,

Jackson has waived this assignment of error. Rule 5:25.

PRE-TRIAL

A. Motion to Suppress

In his first assignment of error, Jackson asserts

that the trial court erred in failing to suppress the confession Jackson

made to the Newport News police officers while detained in the King

George County Jail. Jackson asserts that the confession should have been

suppressed because he did not knowingly and intelligently waive his

constitutional rights to counsel and against self-incrimination and

because the confession itself was not given voluntarily.

Longstanding principles of federal constitutional law

require that a suspect be informed of his constitutional rights to the

assistance of counsel and against self-incrimination. Miranda v.

Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 471, 86 S.Ct. 1602, 16 L.Ed.2d 694 (1966). These

rights can be waived by the suspect if the waiver is made knowingly and

intelligently. Id. at 475, 86 S.Ct. 1602. The Commonwealth bears the

burden of showing a knowing and intelligent waiver. Id. Whether the

waiver was made knowingly and intelligently is a question of fact that

will not be set aside on appeal unless plainly wrong. Harrison v.

Commonwealth, 244 Va. 576, 581, 423 S.E.2d 160, 163 (1992).

At the suppression hearing, Detective Larry P. Rilee

testified that he informed Jackson of his Miranda rights when he began

questioning Jackson at the King George County Jail around 2:50 p.m. on

August 29 and that Jackson orally waived those rights at that time.

Detective Rilee began taping the interrogation about 25 minutes later.

The transcript of the taped portion of the interrogation recites that

Detective Rilee stated, “We've advised you of your Miranda Rights, you

understood those is that correct?” Jackson responded, “That's correct.”

Following this exchange, Jackson made a statement confessing to the

murder of Mrs. Kaiser.

Jackson asserts that because Detective Rilee did not

use a written waiver of rights form and did not repeat the elements of

the Miranda warning during the taped portion of the interrogation, the

record is insufficient to show that Jackson intelligently and knowingly

waived his Miranda rights. We disagree.

A valid waiver of Miranda rights does not require the

waiver to be in writing. Harrison, 244 Va. at 583, 423 S.E.2d at 163.

Detective Rilee's testimony and the transcript of the interrogation

support the trial court's factual determination that Jackson was

informed of his Miranda rights and that he knowingly and intelligently

waived those rights.

Jackson also contends that his confession was not

voluntary because it was not the product of his free and unconstrained

will. Whether a confession was voluntary is a legal question to be

resolved by the court, considering all the circumstances. Roach v.

Commonwealth, 251 Va. 324, 341, 468 S.E.2d 98, 108 (1996).

Jackson maintains that the officers conducting the

interrogation overbore his will. The police officers, according to

Jackson, applied psychological pressure and engaged in trickery, and

lied to him about the evidence connecting him with Mrs. Kaiser's death.

These actions along with his conditions of confinement resulted in a

confession that, he argues, he did not voluntarily make. We disagree

with Jackson.

Jackson recites a number of factors that, he argues,

rendered his statement involuntary. Prior to and during his

interrogation, he was tired, hungry, and kept in a “freezing” cell.

According to his court-appointed expert psychologist, Dr. Stephen C.

Ganderson, the verbal performance component of Jackson's IQ was below

average although his overall IQ was in the normal range. Jackson further

maintains that he was told that if he made a statement he could call his

mother, and he stated that the promise was the reason he gave the

statement confessing to the murder.

We agree with the trial court that neither the expert

testimony nor the adverse conditions Jackson alleged constituted

sufficient evidence that Jackson suffered from an impaired ability to

understand what he was doing or saying, or that his ability to decide

whether to give a statement of his own free will was overcome. As noted

by the trial court, the degree of detail in Jackson's confession belies

his assertion that he only gave the statement to secure the right to

telephone his mother.

The interrogation methods used by the officers in

this case do not render this confession involuntary per se. Smith v.

Commonwealth, 219 Va. 455, 470, 248 S.E.2d 135, 144-45 (1978).

Furthermore, the record shows that Jackson did not cite police trickery

or deceit as a ground for suppressing his confession in the trial court.

Jackson has not preserved that argument for consideration here. Rule

5:25.

Based on our review of the record, we hold that

Jackson confessed voluntarily and that the trial court did not err in

concluding that Jackson knowingly and intelligently waived his Miranda

rights.

B. Polling Jurors

In a pre-trial motion, Jackson asked that, if the

jury imposed the death sentence based on the aggravating factor of

vileness, the jury be polled as to “which statutory element(s)

established vileness, specifying at the time of polling one or more of

torture, depravity of mind or aggravated battery.” To that end, Jackson

requested jury instructions and a verdict form that required unanimity

on one or more vileness elements. Relying on Richardson v. United States,

526 U.S. 813, 119 S.Ct. 1707, 143 L.Ed.2d 985 (1999), Jackson argues

that when imposing the death sentence, due process requires unanimity

not only as to the aggravating factor of vileness but also to one or

more of its composite elements.

This Court has rejected the proposition that the jury

must identify the element or elements of the vileness factor upon which

it based its decision. Clark v. Commonwealth, 220 Va. 201, 213, 257

S.E.2d 784, 791 (1979). The Supreme Court's decision in Richardson does

not require us to revisit our decision in Clark.

Richardson involved a prosecution for engaging in a

continuing criminal enterprise. As relevant here, conviction required

proof that the defendant committed a specific federal offense and that

the offense was part of a “continuing series” of offenses undertaken by

the defendant in concert with five or more other persons.

The trial court instructed the jury that it had to

find unanimously that the defendant committed at least three federal

narcotics offenses but did not have to agree as to the particular three

offenses. The Supreme Court reversed, holding that the several

violations required for conviction were an element of the offense and

thus the jury had to agree on the same three violations. Richardson, 526

U.S. at 819-20, 824, 119 S.Ct. 1707.

The Supreme Court explained in Richardson that, for

example, the jury must unanimously find force as an element of the crime

of robbery, but whether the force is created by the use of a gun or a

knife is not an element of the crime and therefore does not require jury

unanimity. Id. at 817, 119 S.Ct. 1707.

In this case, the element the jury was required to

find unanimously to impose the death sentence was the aggravating factor

of vileness, which requires the defendant's actions be “outrageously or

wantonly vile, horrible or inhuman.” Code § 19.2-264.2. Depravity of

mind, aggravated battery, and torture are not discrete elements of

vileness that would require separate proof but rather are “several

possible sets of underlying facts [that] make up [the] particular

element.” Richardson, 526 U.S. at 817, 119 S.Ct. 1707. Neither Clark nor

Richardson, therefore, requires juror unanimity on these points.

Accordingly, we reject this assignment of error.

GUILT PHASE

A. Juror Disqualification

Jackson charges that the trial court erred in not

striking Sandra Peiffer from the jury panel for cause.

Absent manifest error, we will not disturb the trial

court's judgment whether to strike a potential juror for cause. Green,

266 Va. at 98, 580 S.E.2d at 844; Clagett v. Commonwealth, 252 Va. 79,

90, 472 S.E.2d 263, 269 (1996). The law does not require that a juror be

ignorant of all facts, only that jurors be impartial. Breeden v.

Commonwealth, 217 Va. 297, 300, 227 S.E.2d 734, 736 (1976).

During voir dire, Peiffer volunteered that she had

read newspaper accounts about the case and remembered that the person

charged with the crime had made some comments to the newspaper earlier.

Peiffer did not remember the name of the person. She went on to say,

however, that she had not formed an opinion on the defendant's guilt and

repeated that she would decide the case based on the evidence produced

at trial.

Because the person interviewed by the media was

Dorsett and not Jackson, Jackson maintained that Peiffer could not be

impartial and would taint the jury if she told them her recollections of

the newspaper account. The trial court refused to strike Peiffer for

cause, finding that the juror was “very, very emphatic” about her

ability to decide the case solely on the law and on the evidence.

Peiffer's statements, taken as a whole, demonstrate

that she would be impartial in deciding the case. We find no error in

the trial court's decision not to strike Peiffer for cause.

B. Batson Challenge

In Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79, 89, 106 S.Ct.

1712, 90 L.Ed.2d 69 (1986), the United States Supreme Court held that

excluding a potential juror solely on the basis of the juror's race is

purposeful discrimination and a violation of the Equal Protection Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution. In his

tenth assignment of error, Jackson claims that the trial court erred in

rejecting his claim that the Commonwealth violated the rule in Batson

because the Commonwealth exercised all five of its peremptory strikes

against African-Americans.

When a defendant raises a challenge based on Batson,

he must make a prima facie showing that the peremptory strike was made

on racial grounds. At that point, the burden shifts to the prosecution

to produce race-neutral explanations for striking the juror.

The defendant may then provide reasons why the

prosecution's explanations were pretextual and the strikes were

discriminatory regardless of the prosecution's stated explanations.

Whether the defendant has carried his burden of proving purposeful

discrimination in the selection of the jury is then a matter to be

decided by the trial court. The trial court's findings will be reversed

only if they are clearly erroneous. Buck v. Commonwealth, 247 Va. 449,

450-51, 443 S.E.2d 414, 415 (1994).

In this case, the Commonwealth offered the following

explanations for the exercise of its peremptory strikes against five

African-Americans: FN1

FN1. The Commonwealth argues that it was not required

to offer race-neutral explanations because Jackson did not make a prima

facie showing of purposeful discrimination. This argument was not made

in the trial court, was not asserted as cross-error, and we do not

consider it here. Rule 5:25.

(1) The Commonwealth struck Charles Blanco because he

was previously represented by one of the defense attorneys and would be

more likely to believe that attorney. Mr. Blanco also was concerned

about the impact of the trial on his responsibility to take care of his

children who had special needs.

(2) Amy Leggett was struck because she answered that

she did not believe in the death penalty and even though she said she

could apply it, “she would have a very, very hard time in applying the

laws and evidence.”

(3) Vento Carter, according to the Commonwealth,

changed his position throughout his voir dire, stating initially he

would impose a higher standard of proof on the Commonwealth but then

stating that he could nevertheless listen to the instructions of the

court on the Commonwealth's burden. Carter also changed his position

with regard to the necessity of the defendant testifying. The

Commonwealth stated it had no “faith” in Carter's final answers.

(4) The Commonwealth struck Geraldine Thomas because

she stated that she would have to have “no doubt” as to the guilt of the

defendant before imposing the death penalty regardless of what the court

said.

(5) Christopher Sledge testified that he would hold

the Commonwealth to a higher standard even though he supposed he could

follow the court's instructions. Sledge also stated that he “didn't like”

the death penalty.

The trial court concluded that these explanations

were race-neutral and rejected Jackson's Batson challenge. FN2. Jackson

did not assert that these answers were pre-textual.

On appellate review, the trial court's conclusion

regarding whether reasons given for the strikes are race-neutral is

entitled to great deference, and that determination will not be reversed

on appeal unless it is clearly erroneous. Wright v. Commonwealth, 245

Va. 177, 186, 427 S.E.2d 379, 386 (1993), vacated and remanded on other

grounds, 512 U.S. 1217, 114 S.Ct. 2701, 129 L.Ed.2d 830 (1994).

The trial court has the unique opportunity to observe

the demeanor and credibility of potential jurors during voir dire, and

the record supports the Commonwealth's characterization of the

statements made by the potential jurors in question. Based on our review

of the record, we conclude that the trial court's ruling on Jackson's

Batson challenge was not clearly erroneous.

C. Question Regarding Failure to Cooperate

Jackson complains that the trial court improperly

allowed the Commonwealth to cross-examine his court-appointed DNA expert,

Shawn Weiss, regarding the witness' refusal to meet with the

Commonwealth's DNA expert.

In his direct testimony, Weiss testified that he did

not conduct independent testing of the DNA samples but questioned the

Commonwealth's testing results in a number of areas. During cross-examination,

Weiss acknowledged that the Commonwealth had attempted to set up a

meeting between Weiss and the Commonwealth's DNA experts to “talk about”

and “look at each other's calculations.”

The Commonwealth then asked Weiss why he had not

agreed to the meeting. Weiss replied that he was “under the direction of

the person that hired [him].” The Commonwealth went on to ask if Weiss

knew that the Commonwealth had “just opened everything up, showed it, no

requests having been made.” At this point Jackson objected, saying that

the Commonwealth's questioning implied that “somehow we weren't

following the rules.” The trial court overruled the objection.

Jackson argues here that the Commonwealth's

questioning misled the jury because it implied that Jackson did not

adhere to the rules of discovery. FN3 The Commonwealth responds, that by

asking the reasons for Weiss' refusal to meet with the Commonwealth's

DNA experts, it was exploring Weiss' credibility, potential bias and the

basis of his opinions.

FN3. Jackson also asserts that the exchange violated

his constitutional rights of due process. He did not make this argument

in the trial court and we do not consider it here. Rule 5:25.

Cross-examination of a witness to establish or

explore the bias of that witness based on a relationship to a party in

the case is proper. Goins v. Commonwealth, 251 Va. 442, 465, 470 S.E.2d

114, 129 (1996). Furthermore, limitation of cross-examination is within

the trial court's discretion. Norfolk & Western Railway Co. v. Sonney,

236 Va. 482, 488, 374 S.E.2d 71, 74 (1988).

In this case Weiss' statement that he refused to meet

with the Commonwealth's DNA experts because of his relationship to the

defense could have reflected bias. Accordingly, we cannot say that the

trial court erred in overruling Jackson's objection to the

Commonwealth's question.

D. Expert Testimony on False Confessions

Jackson argues in his fourteenth assignment of error

that the trial court incorrectly barred Jackson from asking his expert

witness, Dr. Steven C. Ganderson, “a hypothetical question about false

confessions.” FN4 While the trial court was willing to permit Dr.

Ganderson to testify generally regarding circumstances that could lead

to false confessions, it forbade Dr. Ganderson from testifying about the

truth or falsity of Jackson's statement. We find no error in the trial

court's ruling.

FN4. Jackson does not isolate any specific question

in his brief.

The physical and psychological environment

surrounding a confession can be very relevant in determining whether a

confession is reliable, and expert witnesses may testify “to a witness's

or defendant's mental disorder and the hypothetical effect of that

disorder.” Pritchett v. Commonwealth, 263 Va. 182, 187, 557 S.E.2d 205,

208 (2002). Expert witnesses may not, however, render an opinion on the

defendant's veracity or reliability of a confession because whether a

confession is reliable is a matter in the jury's exclusive province. Id.

During voir dire, the trial court accepted Dr.

Ganderson as an expert on psychology and sexual-psychological issues.

Jackson elicited testimony from the doctor on the factors that

contribute to “transference,” a phenomenon in which a subject becomes

more prone to suggestion and may say things which are untrue in an

attempt to gain approval from an authority figure.

Dr. Ganderson also testified about antecedents and

objective goals of a defendant that could affect the reliability of a

defendant's statements. While the trial court permitted this questioning,

it sustained the Commonwealth's objection when Dr. Ganderson questioned

the veracity of Jackson's statement based on transference theory. The

trial court, relying on our decision in Pritchett, ruled that Dr.

Ganderson could testify regarding the circumstances surrounding

Jackson's confession but not about its truth:

Now, I still think in terms out of what he can't say,

that's a false confession. I think the jury still has to make those

kinds of conclusions. Those are factual conclusions, but he can testify

about the surroundings and what he believes the impact has on this

defendant with his mental capacity as well as the surroundings of the

circumstances out of which the confession was taken.

There is no error in this holding.

E. Negative Evidence of Reputation

Jackson asserts that the trial court erred in

“preventing Jackson from presenting certain so-called ‘negative’

evidence of good character.” Jackson refers specifically to the

testimony of two individuals he called as character witnesses. Jackson

asked the witnesses if they were aware of or had heard that Jackson had

a reputation in the community for being violent. The Commonwealth

objected, stating that before asking a question of this sort, Jackson

had to establish that the witness was aware of Jackson's reputation in

the community. The trial court sustained the objections.

This assignment of error is without merit. Jackson

was not prohibited from presenting negative evidence of good character.

Negative evidence of good character is based on the theory that a person

has a good reputation if that reputation has not been questioned. Zirkle

v. Commonwealth, 189 Va. 862, 871-72, 55 S.E.2d 24, 29-30 (1949). It is

admissible, as is other reputation evidence, if the proper foundation is

established. See Barlow v. Commonwealth, 224 Va. 338, 340-41, 297 S.E.2d

645, 646 (1982). Thus, a witness must be aware of the party's reputation

in the community before he may testify as to the lack of any reputation

for a particular characteristic.

Jackson did not establish that either witness had

knowledge of Jackson's reputation in the community before asking the

type of question recited above. Accordingly, the trial court not only

was correct in sustaining the Commonwealth's objection to the questions,

but nothing in the record shows that Jackson was prevented from

introducing negative evidence of reputation.

In fact, the record shows that in at least one

instance, Jackson proceeded to establish that the witness had the

requisite knowledge of Jackson's reputation in the community and then

testified that he never “heard anything from anybody of [Jackson] doing

any wrongdoing to anybody.” We find no error in the ruling of the trial

court.

F. Motion to Strike

Jackson asserts that the trial court erred in denying

his motion to strike the Commonwealth's evidence. He argues that the

evidence was insufficient to support his convictions because his

confession was not reliable, the forensic testing was inadequate, and no

other evidence connected him to the crime scene.

In reviewing the record to determine whether the

evidence was sufficient to support the convictions, we consider the

evidence in the light most favorable to the Commonwealth and give the

Commonwealth all inferences fairly deducible from that evidence. Burns

v. Commonwealth, 261 Va. 307, 313-14, 541 S.E.2d 872, 878 (2001).

Jackson argues that his confession was not reliable

for two reasons: his will was overborne by the deception of the officers

and the confession was false. We have already held that Jackson's will

was not overborne, and, therefore, we reject that argument as a basis

for finding his confession unreliable.

Jackson also bases his assertion that his confession

was false on the alleged deception of the officers during his

interrogation. Jackson does not offer, and we cannot find, any rationale

or evidence supporting the conclusion that the tactics utilized by the

officers during his interrogation caused Jackson's confession to be

false.

The forensic testing was inadequate, according to

Jackson, because the DNA testing of the blood mixture on the toe of a

sock found at the crime scene involved only eight loci. Jackson's DNA

loci matched six of the eight loci. The standard procedure of the state

laboratory is to test 13 or 16 loci. Shawn Weiss, Jackson's expert in

DNA testing, testified that, had 13 or 16 loci been tested, there was a

“possibility” that other suspects may have had more loci matches than

Jackson.

Jackson's criticism of the Commonwealth's forensic

testing does not change the fact that some of the loci matched his DNA.

Under these circumstances, as his own expert testified, “Kent Jackson

cannot be excluded as a minor contributor.”

Finally, the lack of other forensic evidence

connecting Jackson to the crime scene does not support the conclusion

that the evidence was insufficient to prove Jackson's guilt beyond a

reasonable doubt. Jackson's detailed confession, corroborated by

evidence of the injuries Mrs. Kaiser suffered, was sufficient to

establish his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. The trial court did not

err in denying Jackson's motion to strike. Clozza v. Commonwealth, 228

Va. 124, 133, 321 S.E.2d 273, 279 (1984).

STATUTORY REVIEW

Under Code § 17.1-313(C)(1), we must inquire whether

passion, prejudice, or any other arbitrary factor affected the

sentencing decision. Jackson contends that “numerous horrific

photographs of the decendant” inflamed the jury and improperly

influenced its sentencing decision. Jackson's argument is not, and

cannot be, that allowing the pictures to be seen by the jury was error.

As discussed above, he did not object to their introduction during the

guilt phase of the trial.

Thus, whether the these pictures were properly or

improperly admitted is not the issue before us in this statutory review.

We do however, consider the potential impact these pictures may have had

on the decision to impose the death sentence. Emmett v. Commonwealth,

264 Va. 364, 371, 569 S.E.2d 39, 44 (2002).

The pictures at issue, while gruesome, accurately

depicted the condition of the victim and were relevant to the “motive,

intent, method, malice, premeditation and the atrociousness of the crime.”

Id. at 372, 569 S.E.2d at 45. In this context, the jury was entitled to

use the photographs to make an informed decision on the defendant's

guilt and the appropriate sentence thereafter.

The record contains ample evidence supporting the

imposition of the death sentence, and nothing in the record suggests

that passion or prejudice played any part in that decision. Code §

17.1-313(C)(2) requires us to determine whether the sentence in this

case is “excessive or disproportionate to the penalty imposed in similar

cases, considering both the crime and the defendant.” Our examination

seeks “ to reach a reasoned judgment regarding what cases justify the

imposition of the death penalty.” Orbe v. Commonwealth, 258 Va. 390,

405, 519 S.E.2d 808, 817 (1999).

We have examined the capital murder cases where

robbery was the predicate offense and where the Commonwealth sought the

death penalty based on the aggravating factor of vileness. Our review

encompassed both cases where the jury fixed the death penalty and where

it fixed life imprisonment. Based on that review, we find that

defendant's sentence was not excessive or disproportionate to sentences

imposed in capital murder cases similar to the instant case. See Bennett

v. Commonwealth, 236 Va. 448, 374 S.E.2d 303 (1988) (defendant bound,

beat, and stabbed victim); Boggs v. Commonwealth, 229 Va. 501, 331

S.E.2d 407 (1985) (defendant beat his 87-year-old neighbor with a piece

of steel and then stabbed her); Bunch v. Commonwealth, 225 Va. 423, 304

S.E.2d 271 (1983)(defendant shot his lover in the head, ransacked her

house, and hung her from a doorknob); LeVasseur v. Commonwealth, 225 Va.

564, 304 S.E.2d 644 (1983) (defendant beat victim and stabbed her with a

carving fork and ice pick); Whitley v. Commonwealth, 223 Va. 66, 286

S.E.2d 162 (1982) (defendant strangled victim, cut her throat, and

inserted umbrellas into her anus and vagina post-mortem ); Coppola v.

Commonwealth, 220 Va. 243, 257 S.E.2d 797 (1979) (defendant entered

house with co-conspirators, robbed victim, and then choked and beat her

to death).

At oral argument, Jackson's counsel argued that the

death penalty should not be imposed in this case because Jackson himself

did not commit some of the more heinous acts involved in the murder of

Mrs. Kaiser, but rather primarily assumed the role of a bystander and

only stabbed Mrs. Kaiser with a knife. Counsel asked this Court to set

aside the death penalty and impose a penalty of life pursuant to the

provisions of Code § 17.1-313(D)(2).

We reject this request. Beulah Mae Kaiser suffered a

brutal, vicious, and painful death at Kent Jermaine Jackson's hands. The

record indicates that Jackson agreed to the plan to enter Mrs. Kaiser's

apartment and rob her and that he kicked her and held her down while

Dorsett punched, kicked, and stabbed her. Jackson stabbed Mrs. Kaiser

and he handed Dorsett the cane that ultimately was shoved through her

face.

For the above reasons we affirm the conviction for

capital murder and the imposition of the death penalty entered in Case

No. 030749 and affirm the non-capital convictions in Case No. 030750.

Jackson v. Johnson, 523 F.3d 273 (4th Cir.

2008) (Habeas).

Background: Following affirmance of first-degree

murder conviction and death sentence, 587 S.E.2d 532, petition for writ

of habeas corpus was filed. The United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia, Walter D. Kelly, Jr., J., 2007 WL 1052547,

denied the petition. Petitioner appealed.

Holding: The Court of Appeals, Williams, Chief Judge,

held that state court determination in rejecting ineffective assistance

of counsel claim did not represent an unreasonable application of

Supreme Court precedent. Affirmed.

WILLIAMS, Chief Judge:

On April 18, 2000, Petitioner Kent Jermaine Jackson

brutally killed Beulah Mae Kaiser, a 79-year-old woman who lived in the

apartment across the hall from him. A Virginia jury convicted Jackson of

first-degree, premeditated murder during the commission of a robbery or

attempted robbery, robbery, felony stabbing, and burglary, all in

connection with Kaiser's death. The jury sentenced him to death for the

first-degree murder conviction.

After unsuccessfully working his way through

Virginia's direct-appeal and post-conviction review processes, Jackson

filed a petition under 28 U.S.C.A. § 2254 (West 2006) seeking habeas

relief in federal court. In his federal habeas petition, Jackson raised

numerous claims, including a claim that his trial counsel was

ineffective under Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 104 S.Ct.

2052, 80 L.Ed.2d 674 (1984), for failing to object to the Commonwealth

of Virginia's closing argument at his sentencing, an argument that

Jackson claims rendered his trial fundamentally unfair and violated the

Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The district court

denied Jackson's petition, and, for the reasons that follow, we affirm.

I.

A.

The grisly facts of Kaiser's murder, as recounted by

the Supreme Court of Virginia in its opinion in Jackson's direct appeal,

are as follows:

On April 18, 2000, the body of Beulah Mae Kaiser, 79

years of age, was found in her apartment. According to the medical

examiner, Mrs. Kaiser died from a combination of a stab wound to her

jugular vein, a fractured skull, and asphyxia caused by blockage of her

airway by her tongue. Any one of these injuries could have been fatal.

In addition to these injuries, Mrs. Kaiser suffered

two black eyes, a broken nose, and multiple abrasions, lacerations, and

bruises. She had five stab wounds to her head and neck, including the

wound to her jugular vein.

The medical examiner also testified that Mrs. Kaiser

had been anally sodomized with her walking cane and that the cane then

had been driven into her mouth with such violence that it knocked out

most of her teeth, tore her tongue and forced it into her airway,

fractured her jaw, and penetrated the left side of her face.

When Mrs. Kaiser's body was found, her apartment was

in disarray. Personal items were strewn throughout the apartment, blood

spatters were on the surfaces of the apartment, and the contents of Mrs.

Kaiser's purse had been dumped on the floor. The police were unable,

however, to find a weapon or any fingerprints of value.

The crime went unsolved for over 16 months until DNA

testing of saliva on a cigarette butt found in the apartment implicated

an individual named Cary Gaskins. An interview with Gaskins led the

police to Joseph M. Dorsett and [Kent Jermaine] Jackson, who had been

roommates in an apartment across the hall from Mrs. Kaiser's apartment

at the time of her death. Following an interview with Dorsett, Newport

News police arrested Dorsett, charging him with Mrs. Kaiser's murder,

and obtained a warrant for Jackson's arrest.

Police arrested Jackson at a girlfriend's home in

King George County around 4:00 a.m. on August 29, 2001. During an

interview with Newport News police detectives at the King George County

jail that afternoon, Jackson confessed to the murder of Mrs. Kaiser.

Jackson v. Commonwealth, 266 Va. 423, 587 S.E.2d 532, 537-38 (2003).

B.

On January 14, 2002, a grand jury in the Circuit

Court for the City of Newport News, Virginia indicted Jackson, charging

him with pre-meditated murder in the commission of a robbery or

attempted robbery, robbery, felony stabbing, burglary, and object sexual

penetration.FN1 Id. at 538. In December of the same year, a jury

convicted Jackson of all counts except the object sexual penetration

count. FN1. The grand jury also indicted Dorsett on the same charges.

According to Jackson's brief, “Dorsett received multiple terms of years

for these crimes.” (Petitioner's Br. at 9.)

Pursuant to Virginia law, a capital sentencing

proceeding was held. Va.Code Ann. § 19.2-264.4 (2004). The jury found

“unanimously and beyond a reasonable doubt that [Jackson's] conduct in

committing the offense was outrageously or wantonly vile, horrible, or

inhuman in that it involved torture, depravity of mind or aggravated

battery to the victim beyond the minimum necessary to accomplish the act

of murder.” (J.A. at 1090 (tracking language from Va.Code §

19.2-264.4(C)).) Based on this finding, the jury recommended that

Jackson be sentenced to death. The trial court accepted the jury's

recommendation and imposed a death sentence.

Jackson appealed, and the Supreme Court of Virginia

unanimously affirmed his convictions and death sentence, Jackson, 587

S.E.2d at 546. The U.S. Supreme Court later denied his petition for a

writ of certiorari, Jackson v. Virginia, 543 U.S. 842, 125 S.Ct. 281,

160 L.Ed.2d 68 (2004).

Shortly thereafter, the trial court appointed Jackson

new counsel to represent him in state post-conviction proceedings, and

on December 2, 2004, Jackson filed a habeas corpus petition in the

Supreme Court of Virginia, raising a host of federal constitutional

claims. One of Jackson's claims focused on the Commonwealth's closing

argument at his sentencing: Jackson argued that, under Strickland, his

trial counsel was ineffective because he did not object to the

Commonwealth's comparing Jackson to his victim and urging the jury to

choose a death sentence based on this comparison. On July 10, 2005, the

Supreme Court of Virginia denied Jackson's petition in a lengthy order,

and the U.S. Supreme Court denied Jackson's attendant certiorari

petition on August 26, 2005. Jackson v. True, 545 U.S. 1160, 126 S.Ct.

29, 162 L.Ed.2d 928 (2005).

Jackson then turned to the federal courts for habeas

relief, filing a 28 U.S.C.A. § 2254 petition in the Eastern District of

Virginia that raised essentially the same federal constitutional claims

presented in his state habeas petition. The Commonwealth filed a motion

to dismiss the petition, and a magistrate judge issued a report and

recommendation that the petition be dismissed. On March 30, 2007, the

district court accepted the magistrate judge's recommendation and

dismissed Jackson's habeas petition.

Jackson timely appealed, and on October 15, 2007,

during the pendency of the appeal, the district court granted Jackson a

certificate of appealability (“COA”) on the following issue: whether,

under Strickland, Jackson's trial counsel was ineffective for failing to

object to the Commonwealth's victim-to-defendant comparison at

sentencing.

*****

This appeal focuses on the Commonwealth's closing

argument at the sentencing phase of Jackson's trial. The argument

proceeded as follows:

Ladies and gentlemen, because the Commonwealth has

proved the aggravating factors does not mean that you're required to

find that death is the appropriate punishment. You may impose the death

penalty. You may.

What you have to do is weigh the evidence to include

the evidence in mitigation. You've taken an oath to take that into

consideration as well. Weigh the evidence to include the defendant's

evidence in mitigation against the defendant's conduct in committing the

crime; the helplessness of the victim and the effects that Kent

Jackson's crime has had on Beulah Mae Kaiser's family, friends and this

community.

That is what the Commonwealth is asking you to do.

The defendant's conduct we've already talked about; clearly horrible,

inhuman. Is there any question this was a defenseless woman? From what

you have heard about her, she had arthritis, she got around on a walker,

she probably would have given Mark Dorsett and Kent Jackson anything

they wanted. There was no need for this. None. It didn't have to happen.

What's the evidence in mitigation against this?

You've heard from his family. Kent Jackson came from a very good family.

There's no doubt about that. The people that took that stand told the

truth about what they know about this person, and when they looked at

the Kaiser family and said they were remorseful for what he did and that

they truly felt pain for this family, they meant it.

I know that every single one of you felt that. They

meant it from the bottom of their hearts, and the Kaiser family felt it,

too.

What did you see from him? He strolled to this

witness stand with his hands in his pockets. Said Mark Dorsett may have

had an influence on Kent Jackson's life, but when he picked up that

sharp instrument, he made the decision to thrust it into Beulah Kaiser's

throat. Mark Dorsett didn't make it for him. As she laid there and he

was kicking her on the ground, he made that decision.

Mark Dorsett didn't make it for him. Mark Dorsett

will be held answerable another day. Today is Kent Jackson's day to be

answerable for what he chose to do and what he did to this woman. Look

at the effects that this crime has had on Beulah Mae Kaiser's family,

friends and on this community.

As I listened to this testimony today, I couldn't

help but realize that what we're talking about here are two lives that

were completely opposite. You had Beulah Mae Kaiser who literally during

her life lost everything material, just about everything you can lose,

and who only sought to give. She lost what she had and she wanted to

give more.

Then you have Kent Jackson who was given everything

and only sought to take more. This family has lost an incredible person.

I've only gotten to know Beulah Kaiser through talking to family and

friends, but from what you have heard about her, it's not only clear

that this family lost her, we lost her. People like her don't come along

every day. She was a gift to the community, and when Kent Jackson went

in there that day and took rings and coins and worthless trinkets, he

took something far more valuable, something that can never be replaced.

Weigh the life he had against what he has taken, and

when you do you will know that the appropriate punishment for capital

murder is death. (J.A. at 1014-1016.)

In his Virginia habeas petition, Jackson contended

that his trial counsel was constitutionally ineffective for failing to

object to this closing argument because the Commonwealth's comparison of

Jackson to his victim severely prejudiced the proceedings, thus

rendering the trial fundamentally unfair and violative of the Fourteenth

Amendment's Due Process Clause. Although Jackson acknowledged that the

U.S. Supreme Court approved of the use of victim-impact evidence in

Payne v. Tennessee, 501 U.S. 808, 111 S.Ct. 2597, 115 L.Ed.2d 720

(1991), he argued that our panel decision in Humphries v. Ozmint, 366

F.3d 266 (4th Cir.2004), made clear that Payne does not allow for the

kind of victim-to-defendant comparison that the Commonwealth made during

its closing.

The Supreme Court of Virginia rejected Jackson's

Strickland claim on the merits. Rendering its decision on Jackson's

habeas petition after the en banc Humphries court vacated the panel

opinion and reinstated the death sentence in that case, Humphries v.

Ozmint, 397 F.3d 206, 226-27 (4th Cir.2005)(en banc), the Supreme Court

of Virginia ruled as follows:

The Court holds that [Jackson's ineffective-assistance]

claim satisfies neither the “performance” nor the “prejudice” prong of

the two-part test enunciated in Strickland. This Court has previously

held that “victim impact testimony is relevant to punishment in a

capital murder prosecution in Virginia.” Weeks v. Commonwealth, 248 Va.

460, 450 S.E.2d 379, 389-90 (1994).

The record, including the trial transcript,

demonstrates that the Commonwealth's comments about the victim and

petitioner were based on evidence already in the record. Petitioner does

not argue that the comments, standing alone, were factually inaccurate

or unsupported by the record. Petitioner concedes that the United States

Supreme Court approved the use of victim impact evidence in Payne v.

Tennessee, 501 U.S. 808, 111 S.Ct. 2597, 115 L.Ed.2d 720 (1991), but

argues there is a judicial movement towards recognizing that victim

impact statements and argument could be “so unduly prejudicial that it

renders the trial fundamentally unfair.” Id. at 825, 111 S.Ct. 2597.

In support of this argument, petitioner asks this

Court to consider Humphries v. Ozmint, 366 F.3d 266 (4th Cir.2004). The

United States Court of Appeals, however, has since vacated that panel

opinion and affirmed the judgment of the district court, holding that

the South Carolina Supreme Court did not err when it held that the

solicitor's comparison of the defendant's life to that of the victim in

closing argument during the sentencing phase did not render the trial

fundamentally unfair. Humphries v. Ozmint, 397 F.3d 206, 226 (4th

Cir.2005)(en banc). Thus, petitioner has failed to demonstrate that

counsel's performance was deficient or that there is a reasonable

probability that, but for counsel's alleged error, the result of the

proceeding would have been different.

*****

Jackson concedes, as he did before the Supreme Court

of Virginia, that Payne permits the admission of victim-impact evidence

at capital trials, but he claims that Payne clearly established that

arguments of the sort made by the Commonwealth at his trial-those he

styles as comparing the worth of the victim to the defendant-render

capital trials fundamentally unfair in violation of the Due Process

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Our en banc court has previously rejected this very

characterization of Payne. See Humphries, 397 F.3d at 224. In Humphries,

we stated what is obvious from the Payne opinion itself: “the Payne

Court did not disapprove of comparisons between the defendant and the

victim.” Id. at 224.

The Payne Court did allow for the possibility that a

petitioner could make out a Fourteenth Amendment due-process claim “[i]n

the event that [victim-impact] evidence is introduced that is so unduly

prejudicial that it renders the trial fundamentally unfair,” 501 U.S. at

825, 111 S.Ct. 2597, but it did not “set the parameters of what type of

victim-impact evidence would render a trial fundamentally unfair under

the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,” Humphries, 397 F.3d

at 218. See also id. at 231 (Luttig, J., concurring)(noting that Payne

does not address victim-to-defendant comparisons); Humphries v. State,

351 S.C. 362, 570 S.E.2d 160, 167 (2002) (“ Payne does not indicate any

concern about comparisons between the victim and the defendant.”).

Indeed, as the Humphries en banc court pointed out,

Payne's only reference to comparative worth arguments was its

observation that, as a general matter, victim impact evidence is not

offered to make victim-to-victim comparisons. Humphries, 397 F.3d at 224

(citing Payne, 501 U.S. at 823, 111 S.Ct. 2597). Because Payne does not

expressly disapprove of victim-to-defendant comparisons at trial, we

held in Humphries that the South Carolina Supreme Court did not

unreasonably apply Strickland in concluding that Humphries's trial

counsel was constitutionally effective despite not objecting to the

comparisons between Humphries and his victim. Humphries, 397 F.3d at

222-23.

The same reasoning holds true in this case. In light

of Payne's silence regarding victim-to-defendant comparisons, we cannot

say that the Supreme Court of Virginia unreasonably applied Payne in

rejecting Jackson's purported comparative-worth argument. More to the

point, we believe that a reasonable attorney in the shoes of Jackson's

trial counsel would not have felt compelled by Payne to object on the

ground that the Commonwealth's closing argument violated Due Process.

Even assuming arguendo that Jackson's counsel should

have objected to the Commonwealth's closing argument, however, Jackson

has not demonstrated a reasonable probability that the objection would

have led to a result other than a death sentence. As was true in

Humphries, the evidence concerning the appropriate sentence for Jackson

was “not close.” Humphries, 397 F.3d at 222. Jackson confessed to

murdering Beulah Mae Kaiser, and the autopsy revealed the brutality of

the murder. The Commonwealth's closing argument surely “did not inflame

[the jury's] passions more than did the facts of the crime.” Payne, 501

U.S. at 831, 111 S.Ct. 2597 (O'Connor, J., concurring).

III.

In sum, we cannot say that the Supreme Court of

Virginia incorrectly, let alone unreasonably, applied Strickland in

denying Jackson habeas relief. Accordingly, for the aforesaid reasons,

the judgment of the district court is AFFIRMED.