The crime occurred on May 23, 1981 in Jacksonville, Florida. The main witness against Jones later recanted. Two key officers in the case had left the Jacksonville Sheriff's Office under a cloud, and allegations that one of them beat Jones before he supposedly confessed had gained credence.

A retired police officer, Cleveland Smith, came forward and said Officer Lynwood Mundy had bragged that he beat Jones after his arrest. Smith, who described Mundy as an "enforcer", testified that he once watched Mundy get a confession from a suspect by squeezing the suspect's genitals in a vise grip. He said Mundy unabashedly described beating Jones. Smith waited until his 1997 retirement to come forward because he wanted to secure his pension.

More than a dozen people had implicated another man as the killer, saying they either saw him carrying a rifle as he ran from the crime scene or heard him brag he had shot the officer. Even Florida Supreme Court Justice Leander Shaw, who formerly headed a division of the state attorney's office, wrote that Jones' case had become "a horse of a different color". Newly discovered evidence, Shaw wrote, "casts serious doubt on Jones' guilt".

Shaw and one other judge voted to grant Jones a new trial. However, a five-judge majority ruled against Jones and Jones was executed by electric chair one week later, on March 24, 1998, at the age of 47.

Florida executes second killer in 2 days

March 24, 1998 - CNN.com

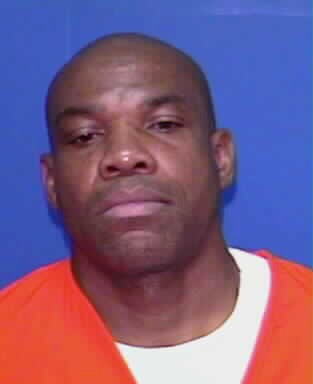

Florida has carried out its second execution in two days, putting to death a man convicted in the 1981 murder of a Jacksonville police officer. Leo Jones, 47, who had argued that the use of a 75-year-old electric chair was cruel and unusual punishment, died in it on Tuesday morning.

Jones' attorneys objected after the fiery death of another inmate on March 25, 1997, when flames leaped from the head of an inmate during an execution in the wired, wooden chair known as "Old Sparky."

The attorneys had filed an appeal, arguing that Florida's method of execution was cruel and unusual and therefore in violation of the state and U.S. constitutions.

The problem led to a yearlong halt in executions in Florida, which ended on Monday when Gerald Stano, 46, died in the state's electric chair for the 1973 murder of a 17-year-old girl. Stano had confessed to 41 killings.

"I bear witness that there is no God but Allah and Muhammad is his messenger," Jones said repeatedly during preparations while staring at his religious adviser, El Hajj Rabbani Muhammad.

When the jolt hit, Jones' fingers tightened and he flinched. As a physician's assistant held a stethoscope to his chest afterward he breathed at least once.

Jones' execution was the 41st since Florida's death penalty was upheld in 1976. The last time the state had back-to-back executions was in December 1995.

Jones was condemned for the 1981 slaying of Thomas Szafranski, who was struck in the head by a sniper's bullet while sitting in his patrol car in downtown Jacksonville.

"In the hearts of all us, it's long overdue," Thomas Pialorsi, who was president of the Jacksonville Fraternal Order of Police when Szafranski was shot, said Monday.

Jones confessed to the shooting, saying he killed the officer because of police beatings. But he later denied the killing, saying the confession was coerced.

In his appeals, he noted the statements of a dozen people who said another man had confessed to the killing. Jones' appeal for a stay to the Florida Supreme Court and a separate appeal to a federal judge were rejected Monday.

Flames from electric chair led to delay

The delay in Florida executions began last year after flames up to a foot long burst from behind the mask covering the face of Pedro Medina during his execution. The death chamber filled with acrid smoke.

No problems with the electric chair were reported as Stano and Jones were put to death.

"We've been assured that the chair and all the components are in very good working order," Florida State Prison spokesman Gene Morris told CNN earlier this week.

The Florida Supreme Court in October 1997 cleared the way for resumed use of the chair but if such a method for capital punishment is ever ruled unconstitutional, Florida lawmakers have approved execution by lethal injection.

In 1990, a sponge in the headpiece caught fire during the death of Jesse Tafero. That also led to a temporary halt in Florida executions.

Questions of Innocence: Legal Roadblocks Thwart New Evidence on Appeal

By Steve Mills - Chicago Tribune

December 18, 2000

JACKSONVILLE—By the time Leo Jones was executed in Florida's electric chair in March 1998 for the sniper killing of a police officer, the case that had sent him to Death Row 16 years before had slowly but unmistakably come apart.

The main witness against him had recanted. Two key officers in the case had left the Police Department under a cloud, and allegations that one of them beat Jones before he supposedly confessed had gained credence.

More than a dozen people had implicated another man as the killer, saying they either saw him carrying a rifle as he ran from the crime scene or heard him brag he had shot the officer.

Even Florida Supreme Court Justice Leander Shaw, a former chief of the capital crimes division of the state attorney's office in Jacksonville, wrote that Jones' case had become "a horse of a different color."

Newly discovered evidence, Shaw wrote, "casts serious doubt on Jones' guilt." He and one other judge voted to grant Jones a new trial.

But a five-judge majority of the court ruled that Jones' claims had no merit. One week later, Jones, 47, was put to death.

In the American system of criminal justice, the presumption of innocence vanishes once a defendant has been found guilty, and the burden of proof shifts from the prosecution to the defense.

Although Death Row inmates are given numerous opportunities for appeal—and some have been able to win their freedom—it can be enormously difficult to persuade appeals courts to embrace new evidence of innocence.

Evidence that a defendant could capitalize on at trial has less potency on appeal. Issues of law and procedure, rather than of innocence, dominate.

Those obstacles exist even though some convictions are built on weak foundations. A Tribune investigation of executions in the United States found dozens of cases where prosecutors relied on dubious evidence or lawyers failed to mount a vigorous defense, undermining the belief that when the state employs an irreversible punishment, it must do so with unshakable certainty.

More than two years after Jones was executed, there are lingering doubts about his guilt, and questions about whether the system of appeals in capital cases adequately addresses claims of innocence.

At the same time, a Tribune reinvestigation of Jones' case has uncovered new evidence that corroborates Jones' longstanding claim that his confession was coerced after Jacksonville police beat him.

In an interview with the Tribune, the lead detective on the case said he saw another officer attack Jones while he was in custody and had to pull him off Jones. The detective's admission contradicts his testimony at trial and in later court hearings.

The assistant state attorney who prosecuted the case said in an interview that he suspects that police, angry over the murder of a colleague, physically abused Jones—though he insists Jones was guilty.

"To me, the most disturbing point of the case has always been his confession and the events leading up to his confession," said Ralph N. Greene III, now an attorney in private practice. "That series of facts always bothered me as a prosecutor."

Two jurors at Jones' trial have told the Tribune they now have misgivings about their guilty verdict, saying that from what they now know about the case, the evidence they heard at Jones' trial was incomplete.

"I think we reached a verdict that made sense based on evidence we heard at the time," said Robert Manley, an advertising copywriter who voted for a life sentence.

"But then the evidence changed. That changed my thinking."

Said Nadine Appleby, a retired secretary who voted for a death sentence: "If we had known some of these things that had come up afterward, it might have made a difference."

Heavier burden of proof

In the U.S. system of criminal justice, appellate courts are reluctant to second-guess jury verdicts and usually defer to rulings by trial judges that involve issues of fact. After all, juries and trial judges observe the demeanor of witnesses and are seen as best positioned to judge their credibility.

Recantations, where witnesses disavow earlier testimony for a new version of the truth, are by law viewed skeptically.

New witnesses are viewed with distrust if they have waited years, or even decades, to come forward, rather than offering their account immediately after a crime.

Rules also have been written to bring finality to appeals—in essence, to balance the demands for fairness with a need for efficiency. Deadlines are in place to keep the justice system manageable and to prevent defendants from appealing indefinitely, although they also can hinder defendants who make legitimate, but untimely, claims.

These circumstances make it difficult for a prisoner trying to prove he was wrongfully convicted.

"In a lot of ways, innocence is the worst possible issue someone on Death Row can have," said Michael Mello, a former appellate attorney in Florida who now teaches law at Vermont Law School. "There is such a denial that this sort of thing happens to innocent people."

Perhaps no decision embodied that more than the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in the case of Leonel Torres Herrera, who was convicted of the 1981 murders of two police officers in Texas and executed by injection in 1993.

Herrera's lawyers claimed in federal court that they had evidence showing he was innocent. They argued he deserved a new trial because executing an innocent man violated the Constitution's protections, particularly those against cruel and unusual punishment.

In denying Herrera's appeal, Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote that the trial was the "paramount event" in a case and the "presumption of innocence disappears" once a defendant has been convicted in a fair trial.

In a stinging dissent, Justice Harry Blackmun wrote: "Just as an execution without adequate safeguards is unacceptable, so too is an execution when the condemned prisoner can prove that he is innocent.

"The execution of a person who can show that he is innocent comes perilously close to simple murder."

The demand for efficiency in the system can put procedure over substance as deadlines are strictly enforced.

That is what happened in Virginia to Roger Coleman.

Coleman had been convicted of a 1981 murder and rape, in a case in which prosecutors relied on a jailhouse informant and imprecise scientific evidence. Coleman had an alibi that, if true, would not have allowed him time to commit the crime.

In the mid-1980s, Coleman lost a state court hearing, and his lawyers missed, by one day, a 30-day deadline for filing a notice of intent to appeal. Later, when they went to federal court, arguing Coleman deserved a hearing on charges that the state withheld evidence and that prosecutors presented false testimony, they were rejected.

The U.S. Supreme Court, in a 6-3 decision, also turned them down, citing the missed deadline. Although Coleman had mounted a strong case for innocence, the court dismissed his appeal on procedural grounds.

"This is a case about Federalism," the majority said in an opinion written by Justice Sandra Day O'Connor. The court, she wrote, should respect the rules the states put in place. Less than a year later, in 1992, Coleman, still proclaiming his innocence, was executed.

In at least a half dozen cases, one or more judges on appeal voted to halt an execution because of their concern the defendant might be innocent. Most of these objections were expressed in dissenting opinions.

Earlier this year, on the eve of Freddie Lee Wright's execution, two judges on the Alabama Supreme Court vigorously dissented from the court's decision to allow Wright to be put to death in the state's electric chair.

Wright, a black man convicted of killing a white couple, had two trials. In the first, he came one vote short of winning his freedom after a racially mixed jury deadlocked, voting 11-1 for acquittal. At the second trial, prosecutors used nearly all of their discretionary strikes to remove blacks from the jury pool, and an all-white jury convicted Wright.

Alabama Supreme Court Justice Douglas Johnstone voted to stay the execution, saying the prosecution did not disclose crucial evidence impeaching the credibility of its two key witnesses. Prosecutors also did not tell Wright's lawyers that another man initially had been indicted. But those charges were dropped despite eyewitness identification, a ballistics report matching the man's gun to the crime, and an incriminating statement from his girlfriend.

In a last-ditch appeal before Wright's execution on March 3, his lawyers argued that electrocution was inhumane. In response, Johnstone wrote, "Whether Wright is electrocuted or injected seems insignificant compared to the likelihood that we are sending an innocent man to his death."

A police officer dies

Early on the morning of May 23, 1981, Leo Jones and his cousin Bobby Hammonds were in their apartment at 6th and Davis Streets, just a block from the almost constant rumble of Interstate Highway 95 in Jacksonville.

Jones was a drug dealer with a handful of arrests and a few convictions, including one for shooting a teenager when he was 15.

"Everybody knew that Leo sold drugs," said Mike Chavis, who was an investigator for Jones' appellate lawyers. "He was a drug dealer. That's what he did."

At 1:10 a.m., two shots rang out. One of the bullets, which police later determined was fired from a .30-30 rifle, crashed through the windshield of a police cruiser stopped at the intersection. The bullet hit the wire cage that separates the front and back seats, and a bullet fragment ricocheted into the head of patrolman Thomas Szafranski, 28, killing him.

Within minutes, Jacksonville police officers were searching Jones' building, and when they burst into a second-floor apartment, they found Jones and Hammonds.

Police took both men in for questioning and then charged Jones, who they claimed had confessed. Hammonds gave a statement, saying he saw Jones leave the apartment with a rifle and return after he heard some gunshots.

Before trial, Jones' lawyers tried to get his confession thrown out because, they alleged, it had been obtained through police coercion. Jones claimed that police beat him and put a gun to his head. He said he felt he had no choice but to confess.

Jones, in fact, was taken to the hospital and treated for minor injuries. A lawyer with the public defender's office who saw Jones at a bond hearing shortly after his arrest said Jones had cuts and bruises on his face and neck.

At a pretrial hearing on the validity of the confession, Hammonds disavowed the statement he had given police. He said officers had beaten and threatened him, telling him to implicate Jones.

Police testified that Jones and Hammonds were hurt during a scuffle as the two resisted arrest. Officers denied any physical abuse or coercion. Detective Hugh Eason told the Tribune he simply talked to Jones until he persuaded him to confess.

Further, Jones' lawyers charged that the confession, written by Eason and signed by Jones, was suspect because of the vague description of the weapon as a "gun or rifle."

Eason testified that Jones told him what to write and that Jones then voluntarily signed it.

Judge A.C. Soud denied the motion to throw out the confession. At trial, Hammonds changed his story again, this time testifying against Jones. Jones maintained his innocence, saying he was in bed when the shooting occurred.

As for the motive, prosecutor Greene said that Jones hated the police and was seeking revenge when he shot Szafranski. Jones had been stopped a week before the shooting and, according to the police officer who stopped him, threatened to kill an officer.

The officer's report made no mention of any threat, and Jones denied it.

Police found two .30-30 rifles in Jones' apartment. They ruled out one as firing the bullet, but tests on the other were inconclusive.

Although his fingerprints were on one of the rifles, Jones claimed the guns belonged to Glenn Schofield, an acquaintance he had sold cocaine to that night.

Jones, who was black, was tried and convicted by an all-white jury. Szafranski also was white.

In the jury's eyes, there was ample proof of guilt: Hammonds' testimony, the discovery of the rifles and the confession, always a powerful piece of evidence.

"The evidence was pretty conclusive," said juror Raymond Kitchens.

Jurors then voted 9-3 to recommend that Jones be sentenced to death. The judge accepted the recommendation, which did not have to be unanimous.

Innocence is not an issue

In Jones' first round of appeals, his lawyers went right back to the alleged confession and questioned the judge's decision to let jurors hear it.

By law, the lawyers had to focus exclusively on what happened at trial, such as whether the judge's rulings were proper. They could not offer any new evidence, and their appeals failed.

Over the next five years, as one phase of appeals ended and another began, Jones' new legal team—led by former public defender Robert Link—was able to present new evidence, which it was slowly discovering.

But the lawyers faced a difficult standard if they were to get a court to reconsider his conviction. Florida law at the time required that a defendant not only raise doubts about the jury's verdict, but also present evidence so compelling that a trial judge would find the jury's verdict a mistake and declare a defendant not guilty.

In time, Link and his investigators were able to locate some of the first evidence suggesting that Jones might be innocent and that another man might have been involved.

Link found witnesses who said the shot that killed Szafranski came from the bushes in a vacant lot near Jones' building, not from the building itself as police testified and as the disputed confession stated.

None of them had been called to testify by Jones' lawyer at trial.

"And there was no question these people were there," Link said, "because they were listed on police reports. They weren't very difficult to locate."

Link also began to build a case against Glenn Schofield, the man Jones said had been at the building that night to buy cocaine. Schofield, interviewed by the Tribune in Jacksonville, denied any role in the murder.

Schofield, now 43, has a lengthy criminal history that, according to records, has put him in prison for all but about three of the past 26 years.

In 1974, when he was 17, Schofield pleaded guilty to manslaughter. He served five years, and was released in 1979. The next year, he was charged with murder, but those charges were dropped.

Nine days after Szafranski was killed, according to police and court records, Schofield shot at a police officer following a bank robbery. Schofield, who then escaped twice from jail, eventually pleaded guilty to a weapons charge. After being paroled in 1989, Schofield was convicted of another weapons charge. He was released earlier this year.

One police report shows that Schofield was initially listed as a possible suspect in the Szafranski murder, along with Jones and Hammonds, but apparently was dropped after Jones was charged.

Anthony Hickson, a retired Jacksonville homicide detective who for a time was Eason's partner, told the Tribune that one of his confidential informants told him that Schofield, not Jones, had murdered Szafranski.

Hickson said that after the trial, he turned over this information to either a lawyer or an investigator for the defense—he's not sure which. He would not identify the informant.

Link began gathering evidence that Schofield had admitted to others that he killed Szafranski, and that Schofield was spotted at the scene of the crime just moments after it happened.

Paul Allen Marr, a prison inmate and jailhouse law clerk, told Jones' lawyers he got to know Schofield in the mid-1980s, when both were serving time at Union Correctional Institution. Marr, who was convicted of sexual battery, said Schofield told him that he, not Jones, had killed Szafranski.

Marr, who was paroled earlier this year and now works in construction, told the Tribune: "The more I listened, the more he talked. And before I knew it, he told me he had murdered that police officer. ... He said he had a beef against all those cops."

Marion Manning, who was a girlfriend of Schofield's, put him at the scene of the crime. In an affidavit, she claimed that moments after the shooting, Schofield flagged her down, jumped into her car and told her to drive away.

Link used the new evidence to bolster his claim that Jones' trial lawyer had been ineffective. That attorney, H. Randolph Fallin, had failed to locate the witnesses that Link found.

That was a tough argument to win, though. Fallin, who had a good reputation, testified he had tried to uncover evidence by going into the neighborhood where the murder occurred and looking for witnesses with the aid of Jones' family.

Even with those developments, Link thought it was unlikely that Soud, who heard the evidence, would grant a new trial.

Soud rejected Jones' appeal, and then in 1988 the Florida Supreme Court rejected it, saying the evidence was insufficient.

More witnesses found

The state never wavered in its conviction that Jones was guilty, that Schofield had nothing to do with the murder, and that Jones had received a fair trial.

Curtis French, an assistant attorney general who handled several of the appeals, said the alleged confessions from Schofield either never were said or were just a matter of Schofield "running his mouth."

"Our position on newly discovered evidence," French said, "was that [Jones] didn't have any, or at least it wasn't credible."

In 1991, Jones' lawyers returned to court with more evidence favorable to Jones. This time, the lawyers presented another girlfriend of Schofield's, who said that shortly after the murder, he asked her to tell police if they came looking for him that he was with her when Szafranski was killed. She also claimed that several years after the murder, he bragged about killing Szafranski.

A girlfriend of Jones', meanwhile, said that she was at the apartment building the night Szafranski was shot and saw Schofield running upstairs with a rifle. She said she asked why he was running, and he replied, "Them crackers are after me."

Two other witnesses said in sworn affidavits that they were walking near the apartment building when they heard a shot and saw Schofield running from the building carrying a rifle. The lawyers also presented affidavits from three other prison inmates saying that Schofield had bragged that he, not Jones, had killed Szafranski.

Finally, the lawyers had a sworn affidavit from Hammonds in which he reverted to his testimony that he never saw Jones with a rifle.

Because Jones was scheduled to be executed within a couple of weeks, Soud ordered a hearing on a Sunday afternoon. He denied Jones' appeal.

His reasons were set out in a lengthy opinion in which he said the evidence Jones' attorneys offered still was not so compelling that, if he were to try the Jones case again, he would immediately acquit him.

"It was a compelling case of guilt," Soud said in an interview.

He said Schofield's alleged statements to other inmates were "less than reliable" because no other evidence supported them. He also ruled that they were hearsay and that Schofield didn't say them immediately after the murder, weakening them.

In fact, jailhouse informants often are unreliable. That's because their testimony typically comes in exchange for benefits from prosecutors.

But in the Jones case, the jailhouse informants had little to gain by testifying. The defense could not offer a shorter sentence or a transfer to another prison—the kinds of inducements that prosecutors sometimes provide in exchange for inmate testimony.

Soud cited Jones' alleged confession as a key part of the prosecution case, and as a reason to find that the defense had not overcome its burden. He could not reconcile the confession with Jones' claims of innocence.

When the Jones case reached the Florida Supreme Court, his lawyers won a bittersweet victory. The court, in a ruling that cut new legal ground, acknowledged the standard for newly discovered evidence had been too high and was "almost impossible to meet."

It said the standard "runs the risk of thwarting justice...."

From then on, the court said, newly discovered evidence had to be strong enough that it would likely produce a not guilty verdict at a new trial. It was a subtle but significant difference, but it did not matter.

The court said some of Jones' evidence was not new. Some of the witnesses, the court said, were available for the trial. Others, such as Paul Marr, were presented on an earlier appeal and, consequently, did not qualify as newly discovered.

With much of the evidence stripped from Jones' appeal, the court said his claim did not meet the lower standard.

In some ways, Jones suffered because his attorneys and investigators developed their evidence in a piecemeal fashion over years, rather than in a single burst that could have a dramatic impact on an appeals court.

"It's incredibly frustrating," said Martin McClain, one of Jones' lawyers. "We thought we were solving the case. We thought we were doing all the right things."

In their next appeal, the attorneys offered three more witnesses who placed Schofield at the scene, including one who said he saw Schofield shoot the rifle from the bushes near Jones' apartment. They also presented four more prison inmates to say that Schofield confessed.

But the Florida Supreme Court said this evidence, which the lawyers sought to use to strengthen what they presented before, was redundant or less than persuasive.

Schofield, the court said, might simply have been bragging.

Evidence points to beating

Jones' appellate team eventually uncovered the first real evidence to undercut the police officers' denials that they had physically abused Jones.

A retired police officer, Cleveland Smith, came forward and said Officer Lynwood Mundy had bragged that he beat Jones after his arrest. Smith, who described Mundy as an "enforcer," testified that he once watched Mundy get a confession from a suspect by squeezing the suspect's genitals in a vise grip. He said Mundy unabashedly described beating Jones.

"Every time you asked Lynwood about it, he would recount the entire story," Smith said in an interview with the Tribune. "I must have heard that story at least 10 or 12 times."

Smith, an officer for 24 years before he retired in 1997, said he waited so long to come forward because he wanted to secure his pension. He said the culture of the Jacksonville police force was such that he feared reprisals had he come forward sooner.

Prosecutors did not challenge Smith's credibility.

Recently, Hugh Eason, who was in charge of the investigation, said in an interview that he had to pull Mundy off of Jones outside Jones' apartment. "He hit him, but he didn't bust him up," Eason said. "But he hit him pretty good."

Mundy, in a brief interview at his home, denied any misconduct.

"All I did was arrest that man. I didn't hurt nobody. I was just doing my job," he said.

When Mundy left the department in 1985, it was under a cloud of suspicion.

In 1982, almost a year after Jones went on trial, two officers testified in an internal affairs hearing that Mundy brought false charges against suspects and sometimes perjured himself when testifying in court hearings. "Officer Mundy," one testified, "is just an outright known liar."

A 1985 internal affairs investigation into allegations that Mundy had roughed up a suspect called the incident "an embarrassment" to the department. It was amid that investigation that Mundy resigned.

Eason also came under scrutiny. In March 1987, prosecutors launched an investigation into allegations that Eason had a role in the murder of a used-car lot owner.

Prosecutors presented their evidence to a grand jury, but no charges were filed. After Eason decided to retire in July, the department's internal inquiry was closed.

Eason, who now makes his living repossessing cars, said the allegations against him were false but declined to discuss details.

The prosecutor also ran into trouble. Greene was indicted by a federal grand jury in 1985 on charges he conspired with a county judge to intervene in a dozen cases involving friends.

Greene resigned during the investigation, and he was acquitted at trial.

A Supreme Court divided

On March 17, 1998, the Florida Supreme Court issued its final ruling on Jones' innocence claims. The majority said that "at most," the evidence suggested Schofield might have taken part in the shooting with Jones—a theory of the crime that prosecutors never before suggested.

Two judges, Leander Shaw and Harry Anstead, issued vigorous dissents. Anstead even listed each witness—20 in all—who implicated Schofield or testified to other problems with the case that would help prove Jones' innocence.

Anstead called the evidence "enormous" and said the court was being overly restrictive in how it considered it—so much so that the court threatened "to defeat the ends of justice" by its nearsightedness.

"...we cannot ignore the fact that the State routinely relies on 'jailhouse confessions' to secure convictions in criminal cases, including many murder cases," he wrote. "Obviously the State would have a powerful case against Schofield...."

Shaw argued that appeals courts were supposed to be a "constitutional safety net" to prevent the execution of innocent people.

"The present case is a classic example of that safety net working properly—up to the present point," he wrote. "Although Jones was tried and convicted in 1981, much of the present evidence did not—could not—come to light until now, more than a decade later—after Officer Smith and Schofield's accusers came forward. This evidence vastly implicates Schofield and casts serious doubt on Jones' guilt."

Thomas Crapps, an assistant general counsel in the governor's office, recalled that the Jones case was difficult to resolve for then-Gov. Lawton Chiles. The dissents from Shaw and Anstead weighed heavily on Chiles, who had to approve the execution.

"When you start getting into these cases, you realize how much things change over time and how they're not cut and dried," said Crapps, now in private practice.

On March 24, 1998, Jones was executed.

"What I always wondered about was whether I failed Leo or the system failed him," said McClain, one Jones' appellate attorneys. "And I think that the system failed him. You're calling on the system to look at itself and own up to making a mistake. The system doesn't like to do that." Juror Robert Manley, who then lived in Texas, was on his way to work one morning when he heard on his car radio that Jones had been executed.

He said he pulled over to the side of the road and began to recall his jury duty. He remembered how certain he had been at trial, how he had been impressed by the strength of the evidence, how the prosecutors had systematically erased his doubts.

Then Manley began to think how the certainty he once felt had eroded over the years as he learned more and more about Jones' case.

"It just hit me that something I'd been a part of had come to fruition," he said. "I felt horrible."

Tribune staff writers Maurice Possley and Ken Armstrong contributed to this report.