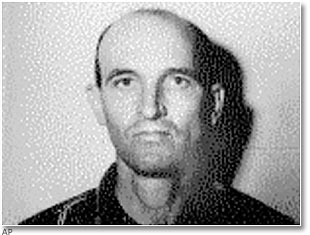

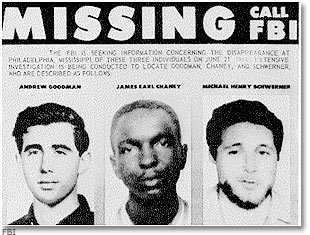

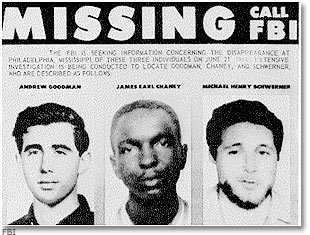

Andrew "Andy" Goodman, a 20-year-old student at Queens College

in New York, was only in Mississippi for one day before he was

killed. The New Yorker was among nearly 1,000 college students,

mostly white, who signed up for "Freedom Summer," a program by

civil rights groups to register Mississippi blacks to vote.

After a training program in Ohio, he drove with Michael

Schwerner and James Chaney to Meridian, arriving the evening of

June 20, 1964. His first assignment was to accompany his

coworkers as they investigated a church burning in Neshoba

County.

He never

returned.

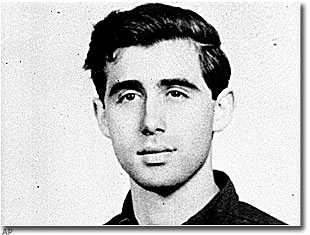

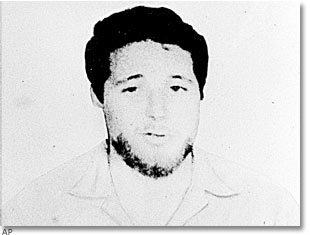

Before coming to Mississippi, Michael Schwerner, 24, was a

social worker in Manhattan. Schwerner, who was from a Jewish

family, told people he was an atheist. He and his wife Rita took

positions with the Congress of Racial Equality, organizing a

boycott of a store that refused to hire blacks and setting up a

community center. Schwerner immediately earned the enmity of the

Ku Klux Klan, which gave him the code name "Goatee." According

to a witness, Schwerner tried to reason with the Klansmen who

killed him, saying to a man aiming a gun at him, "Sir, I know

just how you feel."

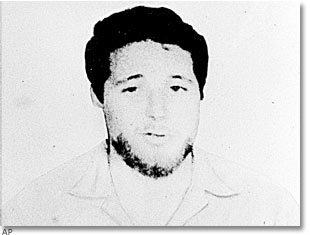

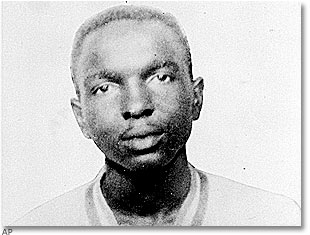

James Chaney was 21 years old and a new father on June 21, 1964.

The only native Mississippian of the victims, Chaney grew up in

Meridian, the eldest of five children. He began working for the

Congress of Racial Equality as a volunteer and later the

Schwerners pushed for him to be hired as a paid staff member. He

was behind the wheel of the CORE station wagon when deputies

stopped the civil rights workers. According to witnesses, he was

the last to be shot.

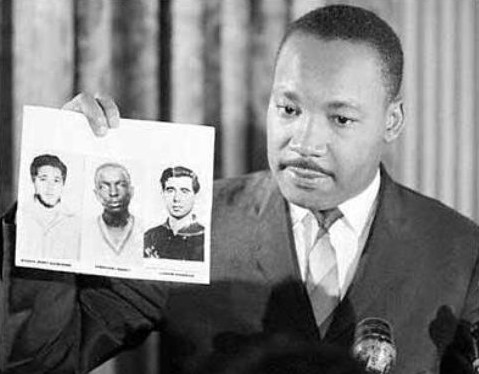

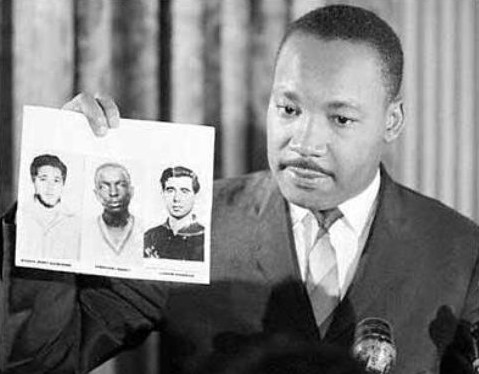

FBI agents took the lead in investigating the disappearances

because local law enforcement agents were unwilling to do so

and, in some cases, were under suspicion. Federal agents

questioned Klan members and helped organized searches of swamps

and fields near Philadelphia. The FBI men paid Klan informants

thousands for their cooperation and the accounts of those

informants were the heart of the federal civil rights case

brought against 18 men in 1967.

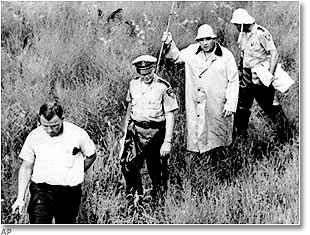

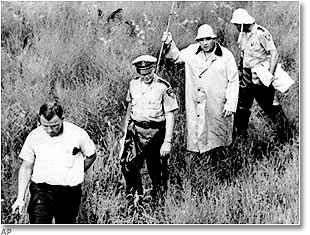

Federal and state investigators as well as Navy recruits combed

snake-infested swamps for signs of the missing civil rights

workers. Forty-four days after they vanished, a tip led to the

discovery of their bodies at the base of an earthen dam near

Philadelphia, Mississippi.

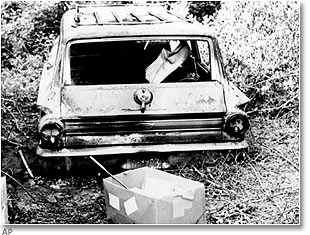

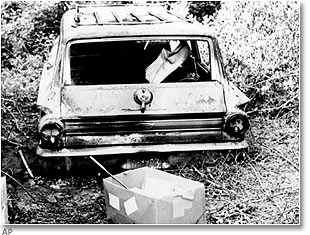

The blue station wagon driven by the trio was recovered in a

swampy area north of Philadelphia two days after they vanished.

The vehicle, owned by the Congress of Racial Equality, had been

set afire.

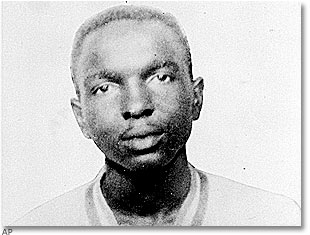

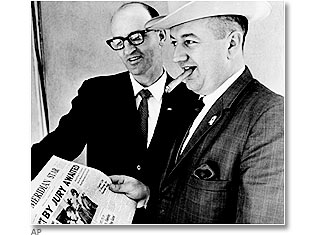

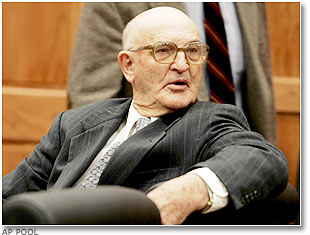

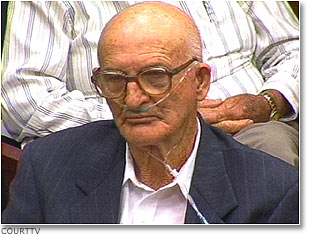

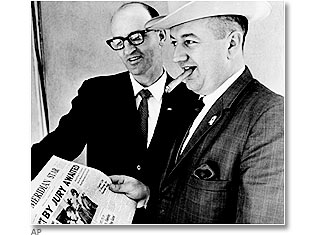

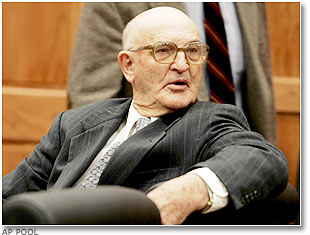

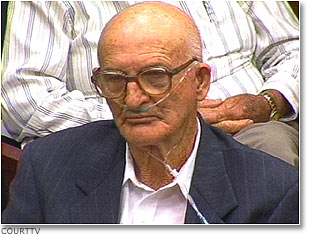

In 1967, 18 men, including Killen (at left) and Neshoba County

Deputy Cecil Price, stood trial on federal civil rights charges.

Price was convicted, but Killen walked free after the jury

deadlocked 11 to 1 in favor of conviction. The holdout juror

said she could not convict a preacher.

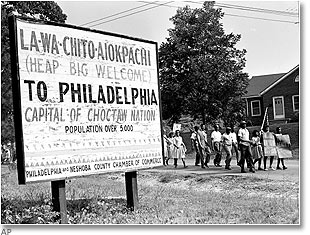

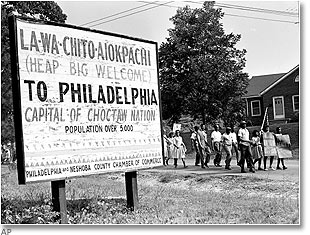

In the wake of the murders, Philadelphia, Mississippi became

synonymous with racial violence. Federal prosecutors pursued

civil rights charges in Meridian, but local prosecutors did not

bring murder charges. A year after the murders, some 60 marchers

marked the anniversary by marching to the site of the church

burning that brought Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner to Neshoba

County.

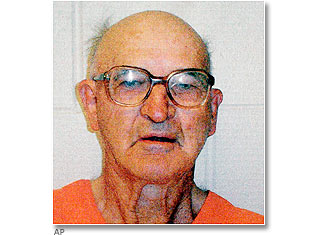

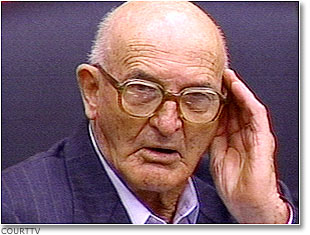

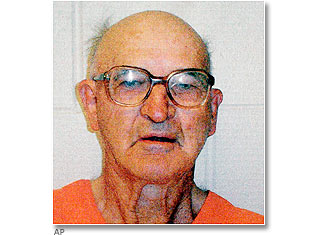

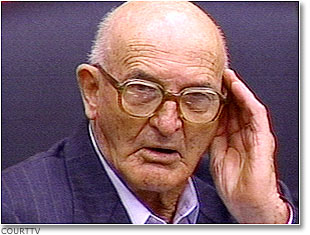

In 1999, state investigators reopened the murder case after a

Klansmen serving a life sentence for another racial murder gave

an interview to a state archivist in which he implicated Killen

as the ringleader. A grand jury indicted 79-year-old Killen,

seen here in his booking photo, in January 2005.

Killen, still working as a preacher and sawmill operator, denied

he was involved in the slayings or ever belonged to the Klan,

but expressed sympathy for those that carried out the murders.

"I'm not going to say they did anything wrong,"

he said.

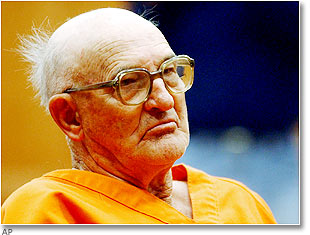

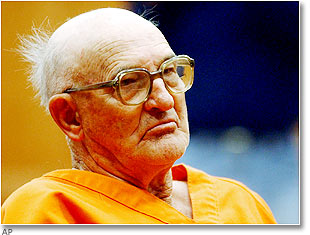

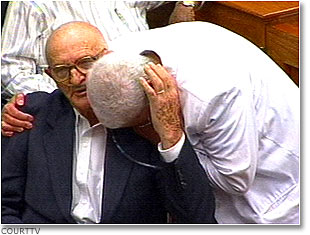

Killen, seen here after his release from Neshoba County

Detention Center on $250,000 bail, insists he did not even know

of Michael Schwerner's existence before the disappearance of the

civil rights workers made headlines.

A lawyer for Killen says his defense will consist of character

witnesses, including fellow Baptist ministers. The defense also

plans to attack testimony from Klan informants, saying the FBI

bought their accounts with thousands of dollars in government

payouts.

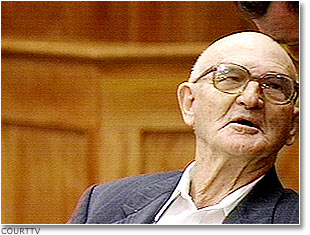

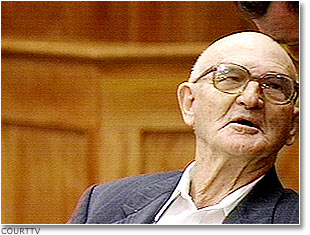

Killen's trial opened one week before the 41st anniversary of

the deaths. Lawyers were only permitted 15 minutes to present

opening statements to the panel of 13 whites and four blacks.

Defense lawyer Mitchell Moran told the jury his client was a

low-level member with no control over the Klan's activities.

State Attorney General Jim Hood acknowledged that Killen did not

shoot the men himself, but said Killen's role as organizer made

him just as guilty as those who fired the guns.

Circuit Court Judge Marcus Gordon halted the trial on its first

day after the 80-year-old defendant was rushed to the hospital

with tightness in his chest and high blood pressure. The recess

came moments after the prosecution's first witness, the widow of

Michael Schwerner, had finished her emotional testimony.

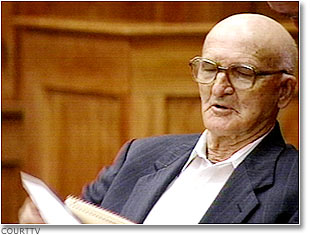

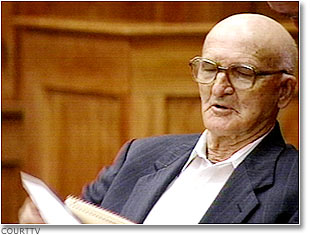

The ailing defendant listened as the jury announced they were

split 6-6 after less than three hours of deliberations. They did

not specify what they were divided on, but said they did not

think further deliberations would make a difference. Even so,

Judge Gordon dismissed them for the evening on June 20, 2005.

The jury returned to deliberate on the 41st anniversary of the

deaths and convicted Killen of three counts of manslaughter.

Killen's wife, Betty, hugged him after the verdict was

announced. She missed a chemotherapy appointment for breast

cancer treatment to attend the proceedings.

Killen's

sentencing was set for June 23.

As Killen was placed into custody, he pushed away microphones

from reporters asking him for comment.