|

Kip's life line

|

January 29, 1972 |

Bill Kinkel marries Faith Zuranski |

|

December 22, 1976 |

Kristin Kinkel is born |

|

August 30, 1982 |

Kipland Kinkel is born. |

|

1986

- 1987 |

The Kinkels take a sabbatical year in Spain

The Kinkels went to Spain for the school year. Kristin,

although in 5th grade, was placed into a 3rd grade class as it

was the only class where the teacher spoke English. Kip went

into his first year of school with a teacher who only spoke

Spanish. Kristin remembered this as a difficult time for Kip. |

|

1989

- 1990 |

Kip repeats first grade at Walterville

Elementary School

After discussions with teachers, the Kinkels decided to hold

Kip back in school for a year. According to court testimony,

Kip's parents and teachers felt that Kip lacked maturity and had

slow emotional and physical development. |

|

1990

- 1991 |

Second Grade: Problems with Language

Kip's second grade teacher testified at his sentencing

hearing that Kip was an average second grader with no

disciplinary problems. She said that written language caused him

great frustration. His parents asked the school to test Kip for

a learning disability to see if he was eligible for special

education services. According to the school counselor, Kip did

not qualify. He scored above the 90th percentile on the

intelligence test, and average on the neurological screening

test. Her only concerns were that he had a remarkably low score

on one motor/hand skill, and that he was having great problems

with spelling. She observed him during the 25 minute spelling

test, and saw that although he worked unusually diligently for

his age, he had difficulty spelling even his own last name, and

his level of frustration and anxiety was abnormally high. |

|

1991

- 1992 |

Third Grade: Special Education

During this year, Bill Kinkel retired from teaching and began

teaching night classes at Lane Community College.

Kip continued to have problems in school with reading and

writing, although he excelled in math. Bill and Faith Kinkel

asked Kip's third grade teacher to retest him for special

education services. This time he qualified, and a plan for

special services was drawn up for him. His third grade teacher

testified in court that Kip was given an honor award at the end

of the year "for improvement in reading and working hard to

overcome his frustration." She also reported that he had no

behavior problems in class and received all As and Bs on his

report card that year. |

|

1992

- 1993 |

Fourth Grade: Learning Disability Diagnosed

Kip continued to qualify for special education services and

was diagnosed with a learning disability. He worked with a

special education counselor for the year. However, according to

his fourth grade teacher, he was simultaneously placed in a

Talented and Gifted program because of his above-average

performance in science and math. |

|

1995

- 1996 |

Seventh Grade: Mail Order Bomb Books

Kristin transferred in her sophomore year of college from

University of Oregon to Hawaii Pacific where she received a full

cheerleading scholarship. After Kristin left home, Kip and some

friends used the internet at school to mail order some 'how to

build bombs' books (e.g. The Anarchist Cookbook). When they were

caught, Faith started to worry more about the friends Kip was

hanging out with, and whether they were bad influences on one

another. |

|

1996

- 1997 |

Eighth Grade: Shoplifting and the Beginning of a

Hidden Gun Collection

Along with some friends, Kip got caught shoplifting CDs from

the local "Target" store. Later that year, he bought an old

sawed-off shotgun from a friend. He kept it hidden in his room.

His parents did not know about it. |

|

January 4, 1997 |

Rock Throwing Incident

Kip went to a snowboarding clinic with a friend in Bend,

Oregon. The two boys were arrested for throwing rocks off a

highway overpass. One of the rocks struck a car below. The

arresting officer said that she caught Kip's friend at the

overpass and found Kip back at the motel where they were

staying. She said Kip started crying, and immediately asked the

officer if anyone was hurt. Kip claimed his friend had actually

thrown the rock that hit the car. Kip and his friend were

charged for the offense and referred to the Department of Youth

Services in Eugene, Oregon. At 11:40 p.m. the Bend police called

the Kinkels, who asked that Kip be held there until they could

come and get him. They drove two hours that same night to pick

Kip up in Bend. |

|

January 20, 1997 |

Counseling: Kip and Faith meet with psychologist

Dr. Jeffrey Hicks

In response to the Bend incident and Faith's rising concern

about Kip's behavioral problems, Faith brought Kip to see

psychologist Jeffrey Hicks. According to Hick's notes, Faith was

worried about Kip. She told Dr. Hicks about the shoplifting and

rock throwing incidents. Faith said that she was concerned about

Kip's temper and his "extreme interest in guns, knives, and

explosives," and was afraid that Kip could harm himself or

others. Faith asked that Hicks help Kip learn more about

appropriate ways to manage his anger and curtail his acting out.

Faith was also deeply concerned with Kip's strained relationship

with his father. Hicks wrote that "Kip became tearful when

discussing his relationship with his father. He reported that

Kip thought his mother viewed him as 'a good kid with some bad

habits' while his father saw him as 'a bad kid with bad habits.'

He felt his father expected the worst from him.

In this meeting Hicks found no evidence of a thought disorder

or psychosis. He diagnosed Kip with Major Depressive Disorder

and concluded that "Kip had difficulty with learning in school,

had difficulty managing anger, some angry acting out and

depression." |

|

January 27, 1997 |

Second counseling session: Slight Improvement

Faith and Kip went for their second meeting with Dr. Jeffrey

Hicks. |

|

February 26, 1997 |

Kip's assessment by the Department of Youth

Services

As a followup to the rock throwing incident in Bend, Kip was

taken to Skipworth Juvenile Facility to meet with psychologist

Dr. John Crumbley. Dr. Crumbley did an intake interview with Kip

and his parents. According to Dr. Crumbley, the Kinkels were

impressive parents. They wanted their son to take responsibility

for what he did and wanted to make things right with the victim.

He said that Kip was not typical of the delinquent kids he

usually sees, in that he was appropriately remorseful and quite

straightforward about his part in the crime. Dr. Crumbley felt

the crime was more of a "boyish" crime and also felt they did

not have a real case against Kip, as he hadn't actually thrown

the rock. It was decided that Kip would complete 32 hours of

community service, write a letter of apology and pay for damages

to the car. Dr. Crumbley saw nothing at all out of the ordinary

with Kip or his family.

Third Counseling Session: Doing Better

Hicks reported that Kip was doing better. He wrote in his

notes that Kip continued to feel depressed several days per week

but denied thought of suicide. |

|

April 4, 1997 |

Fourth Counseling Session: Ongoing Interest in

Explosives

Hicks noted that Kip still had an ongoing interest in

explosives, and that he remained depressed, though less angry. |

|

April 23 - 29 |

Kip gets two suspensions at school

Kip was suspended for two days for kicking another student in

the head after the student shoved him. Kip was angry that the

other boy did not get punished. Soon after, Kip got a three day

suspension for throwing a pencil at another boy. |

|

April 30, 1997 |

Fifth Counseling Session

Faith and Kip discussed the school suspensions with Dr.

Hicks. They both felt the school handled the incidents unfairly

and that the school was not acknowledging how much progress Kip

had made. |

|

June

2, 1997 |

Sixth Counseling Session: Prozac Recommended

According to Hicks's notes, Faith thought that Kip's behavior

had been better, but felt he had also become quite cynical. Dr.

Hicks discussed the use of anti-depressants and recommended Kip

try a course of treatment with Prozac. He wrote: "Kip reports

eating is like a chore. He complains that food doesn't taste

good. He often feels bored and irritable. He feels tired upon

awakening most mornings. He reports there is nothing to which he

is looking forward. He denies suicidal ideation, intent or plan

of action." Hicks forwarded these notes to the Kinkel family

physician with a recommendation that Kip be put on Prozac for

depression. The physician concurred, and four days later Kip

began taking 20 milligrams of Prozac per day. |

|

June

18, 1997 |

Seventh Counseling Session : Prozac seems to be

working

Kip was on Prozac for 12 days. Hicks wrote that Kip was

"sleeping better. No temper outbursts, taking the medication as

prescribed without side effects." He also noted that Kip

appeared less depressed. |

|

June

27, 1997 |

Bill Kinkel purchases a 9mm Glock 19.

Kip went with Bill to buy a 9mm Glock. The understanding

between them was that Kip would do the research on which model

gun he wanted and would pay for it with his own money. He was

not to use the gun without his father present, and the gun would

not become Kip's until he turned 21 years old.

Dr. Hicks made no mention of the gun purchase in his

psychological notes, although in court testimony Hicks stated

that Kip told him that Bill had purchased a handgun for him,

after some persistence on his part, and that it was kept out of

his reach and to be used only under supervision. When asked in

court if he had concerns about buying a gun for Kip when he had

just started on Prozac and had an excessive interest in guns and

firearms, Hicks responded, "No one consulted me about that

decision, and yes, I have concerns about that." |

|

July

9, 1997 |

Eighth Counseling Session : More improvement

Hicks made no mention of the Glock purchase in his session

notes with Faith and Kip. He reported, however, that Faith felt

that Kip was less irritable and generally in a better mood with

no temper outbursts. Hicks also noted that Kip was getting along

well with his parents and his father was continuing to make

efforts to spend time with him. |

|

July

30, 1997 |

Final Counseling Session

Hicks wrote that Kip continued to do well and did not appear

depressed. Hicks, Faith and Kip all agreed that Kip was doing

well enough that he could discontinue treatment. |

|

Summer 1997 |

Another gun

Kip bought a .22 pistol from a friend. He kept it hidden from

his parents. |

|

1997

- 1998 |

Freshman year

Kip entered Thurston High School. According to friends and

parents he did much better in school and things were starting to

look up. Bill Kinkel had his friend, Don Stone, the Thurston

High football coach, call Kip at home and invite him to come out

for the freshman football team. |

|

Fall

'97 |

Kip goes off Prozac after three months. |

|

September 30, 1997 |

Bill buys .22 semiautomatic rifle for his son

Bill bought Kip a Ruger .22 semiautomatic rifle under the

condition that he would use it only under adult supervision.

Again, the gun was bought with Kip's money.

"How to Make a Bomb" speech

Kip gives a talk on "how to make a bomb" in speech class. He

shows detailed drawings of explosives attached to a clock.

According to kids in the class, a girl in the class gave a

speech on how to join Church of Satan, so Kip's topic did not

seem extraordinary. |

|

October 1, 1997 |

Pearl, Mississippi school shootings |

|

December 1, 1997 |

West Paducah, Kentucky school shootings |

|

December 14, 1997 |

Bill confides in a stranger

While at San Diego airport waiting for a flight home from

with a friend, Bill struck up conversation with Dan Close, an

Oregon University professor who specializes in juvenile

violence. They talked for about two hours. They began their

conversation talking about Kristin. Bill said that she was going

to be graduating from college in August. He told Professor Close

how much he was looking forward to going to Hawaii with the

family. According to Dan Close, Bill then saw a forensic book in

Close's bag and started talking about his troubled son. Bill

told Close that in the last couple of years Kip had started

hanging out with a tougher group of kids, playing with

explosives, and that he was becoming difficult to manage, more

secretive and was having troubles in school. |

|

Mar

24, 1998 |

Jonesboro school shootings

According to a friend of Kip's, they watched some of the

school shootings coverage on TV monitors at school and both

said, "Hey, that's pretty cool." |

|

May

1998 |

Toilet papers house

Kip spent the night at Tony McCown's house. They organized a

bunch of friends to beat the school "tp" record. They spent

weeks hoarding toilet paper in Tony's garage. That night, they

snuck out of the house and met ten others at midnight and did a

grand toilet papering job of another house, using over 400 rolls

of toilet paper. They beat the school record but got caught. The

next day, Kip along with the others, had to go clean off the

house. Apparently, he was one of the few kids whose parents

grounded him for the incident. |

|

May

19, 1998 |

Korey arranges to sell Kip another gun

Korey Ewert stole a .32 caliber pistol from Scott Keeney, the

father of one of their friends. He arranged, over the phone, to

sell it to Kip the next day. It is unclear whether Kip knew that

the gun had been stolen from Keeney. |

May 20, 1998 - Day of Kip's Expulsion

|

|

Approx 8:00 a.m. |

Kip buys gun from Korey.

Kip went to school with $110 in cash and bought from Korey a

.32 caliber Beretta semiautomatic pistol, loaded with a 9 round

clip. He put it in paper sack in his locker.

Scott Keeney called the school to report that the gun was

missing and that he thought a friend of his son might have

stolen it. He gave the school a list of about a dozen kids he

thought might be involved. Kip's name was not on the list.

Detective Al Warthen happened to be at the school and

eventually, after talking to a few kids, went to talk to Kip. At

about 9:15 a.m., Kip was pulled out of study hall. Detective

Warthen told him he is there to investigate the disappearance of

a parent's handgun. Kip admitted to having the gun in his

locker. Both Kip and Korey were immediately arrested. They were

promptly escorted off the school premises in police handcuffs

and were suspended from school, pending expulsion. |

|

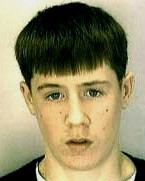

Approx 11:30 a.m. |

Kip is brought to the police station.

Kip was brought to police station. He was fingerprinted,

photographed, and charged with possession of a firearm in a

public building and the felony charge of receiving a stolen

weapon. Detective Al Warthen interviewed him. According to

Warthen Kip was very upset and worried about what his parents

were going to think. He was scared about what was going to

happen to him. Soon after, Bill picked up Kip from the police

station and brought him home. |

|

Approx 2:00 p.m. |

Richard Bushnell calls Bill

Bill Kinkel and Richard Bushnell talked through various

options regarding what to do about Kip. Bushnell said both Bill

and Kip were deeply concerned with how Faith would handle the

news. |

|

3:00

p.m. |

Scott Keeney calls Bill

Scott Keeney called Bill when he heard that Kip had gotten

arrested, and said Bill was very upset. Bill said, "I don't know

what to do at this point." Keeney said Bill was distraught and

thought Kip was completely out of control.

Kip Kills Bill

Kip's father was sitting at the kitchen counter drinking

coffee. According to Kip's confession, he grabbed the .22 rifle

from his room, got ammunition from his parents room, went

downstairs and fired one shot to the back of his father's head.

Kip then dragged his father's body into the bathroom and covered

it with a sheet. |

|

Approx 3:30 p.m. |

Kevin Rowan calls

Rowan is the English teacher from Thurston High. Kip answered

the phone. He told Mr. Rowan that he had made a mistake. He also

told Mr. Rowan that his father was not there right now. |

|

Approx 4:00 p.m. |

Friend calls Kip

Kip's friend asked where Kip's dad was, and Kip said his

father went to the store. Kip's friend said his call waiting was

going off and they got off the phone pretty quickly. |

|

Approx 4:30 p.m. |

Bill Kinkel's Spanish students call

Someone from Lane Community College called to see where Bill

was because he was missing class. Kip answered the phone saying

his father wouldn't make it to class because of "family

problems." |

|

Approx 4:30 p.m. |

Tony McCown and Nick Hiaason conference call

Kip talked on the phone in a conference call with his friends

Tony McCown and Nick Hiaason. Kip told them he didn't know the

gun was Keeney's. He also told them that his dad was out at a

bar. He told them that he was worried about what his parents'

friends would think of what he did, and that his parents would

be so embarrassed when people found out. He kept saying, "It's

over...Everything's over...it's done. ... Nothing matters now."

Kip told Tony and Nick that his stomach was hurting and that he

felt like he was going to throw up. He told them that he just

wanted the gun, that he knew he shouldn't have done it and that

he wasn't planning on doing anything with it. Kip went back and

forth between being upset and angry. According to Tony, Kip kept

asking, "Where's my mom...when is she going to be home?" |

|

Approx 6:30 p.m |

Faith Kinkel arrives home. Kip kills her

Kip met his mom in the garage. According to his audiotaped

police confession, he told her he loved her, and then shot her

twice in the back of the head, three times in the face and one

time through the heart. He dragged her body across the garage

floor and covered her with a sheet. |

May 21, 1998 - Day of School Shooting at

Thurston High

|

|

7:30

a.m. |

Kip leaves house

Kip dressed in long trench coat. He filled his backpack with

ammunition and carried 3 guns: a .22 caliber semiautomatic Ruger

rifle, his father's 9mm Glock pistol and a .22 caliber Ruger

semiautomatic pistol. He taped a hunting knife to his leg and

drove his mother's Ford Explorer to school. He parked one block

from the high school and walked down a dirt path, taking a

shortcut past the tennis courts and into the back parking lot. |

|

7:55

a.m. |

Kip enters school

School security camera recorded his entrance. He walked down

the hallway towards the cafeteria. On the way he shot Ben Walker

and Ryan Atteberry, and then fired off what remained of the 50

round clip from a .22 caliber semiautomatic and one round from a

9mm Glock handgun into the cafeteria. By the time Kip was

wrestled to ground by five classmates, two students were dead

and 25 others were injured. |

|

7:56

a.m |

Springfield Police arrive at the school

Officer Dan Bishop was the first officer on the scene at

Thurston. |

|

8:04

a.m |

Kip Kinkel placed in custody by Dan Bishop.

A bunch of kids were on top of Kip on the floor pinning him

down. Kinkel was identified as the shooter. Bishop got the other

kids off Kip. A student that had been on top of Kip got up and

punched Kip in the face. Kip made statements to the effect: "I

just want to die." Bishop searched Kip and handcuffed him. Kip

was advised of his Miranda rights.

Officer Bishop transferred custody of Kip to Detective Jones,

the first detective to arrive on the scene. Detective Jones

walked Kip to car and secured him there. Kip made no statements

to Detective Jones. Soon after, Detective Al Warthen arrived on

the scene. He was directed by Jones to take custody of Kip and

"get him out of there." Warthen recognized Kip as the kid he had

arrested the day before and took custody of him. |

|

8:50

a.m |

Kip assaults Warthen with knife at the at

Springfield Police Department

Warthen locked Kip in an interview room and left the room for

a moment to set up photo equipment. In the time that he was

gone, Kip managed, with cuffed hands, to pull out the hunting

knife that had been taped to his leg. On the detective's return,

Kip rushed at Warthen with the knife, yelling, "Kill me, shoot

me." Warthen backed up while Kip continued to charge him with

the knife. Warthen got the door to close between Kip and

himself; Kip kept pushing against door. Kip went back to the

chair and started using the knife near his wrists. Warthen

quickly came back in with another detective and sprayed Kip with

pepper spray, while the other detective knocked away the knife. |

|

9:08

a.m. |

Kip tells police he killed his parents

Warthen read Kip his Miranda rights again. Kip indicated that

he understood those rights. Warthen then asked Kip, "How's your

dad?" Kip responded that he killed both of his parents.

Warthen photographed Kip to document physical condition with

clothes on, and then allowed him to shower and clean up. Kip

took off his clothes piece by piece--on his chest he had masking

tape in an X form with one .22 caliber bullet and one .9mm

bullet underneath. Warthen asked him why, and Kip said he put

them there in case he ran out of ammunition; he wanted to have

one of each in which to reload and kill himself. |

|

9:30

a.m. |

Bodies of Bill and Faith Kinkel are found

Three Lane County sheriffs, Detective Spence Slater,

Detective Pam McComas and Deputy Pat O'Neill, arrived at Kinkel

house. They found opera music from the soundtrack to the movie

"Romeo and Juliet" playing loudly on the stereo and set to

continuous play. They could see through glass doors that there

were hundreds of rounds of .22 caliber ammunition strewn all

over the living room floor.

Police searched Kip's room and found what they thought could

be a live bomb constructed from soda cans and one in a fire

extinguisher. They evacuated nearby houses. Later, Sergeant Jim

Fields detonated several explosive devices at the Kinkel home

and found a store of inactive bombs in the crawl space under the

porch. |

|

9:51

a.m. |

Warthen begins a tape recorded interview with

Kinkel.

|

|

May

22, 1998 |

Kip's arraignment

Kip was charged with four counts of aggravated murder. |

|

June

16, 1998 |

Kip Kinkel indicted

He was indicted on 58 felony charges including four counts of

aggravated murder. |

|

September 24, 1999 |

Plea Agreement

Kip pled guilty to four counts of murder and 26 counts of

attempted murder. |

|

November 2, 1999 |

Sentencing Hearing

After a six-day hearing that included the testimony of

psychiatrists and psychologists who interviewed Kip, the

victims' statements, his sister's statement, Lane County Circuit

Judge Jack Mattison sentenced Kip to 111 years in prison,

without the possibility of parole. |

Kipland's life

Kinkel's boyhood troubles explode in rage, destruction

The 16-year-old charged in the

Springfield school shootings, adrift and never measuring up, spiraled

out of control despite his parents vigorous efforts to save him

Kip Kinkel peered out a window of his house.

"Where is she?" he asked nervously, interrupting a

phone conversation with two friends. They had called to console Kip

after he was kicked out of school that day for having a loaded gun in

his locker.

About 30 minutes later, Faith Kinkel's Ford Explorer

turned into the driveway. Kip helped his mom carry groceries into the

kitchen.

He didn't waste time.

"I love you," Kip told her.

He shot her once.

"Please, Mom, close your eyes," Kip urged, when he

saw her breathing a short time later. He shot her two more times -- once

in the face.

By dawn, he'd leave a bomb beneath her body in the

garage.

The once shy, freckled-face boy whom his mother

affectionately called her "li'l angel" police would call a cold-hearted

killer, accused of blasting away his parents and then going on a

shooting rampage at Thurston High School.

Despite accounts by some teachers and friends that

they never saw this coming, a close examination of Kip's life shows his

troubles had festered since he was young.

Interviews with relatives, classmates, teachers,

friends, coaches, neighbors and acquaintances reveal a boy who was

insecure as a young child, was unable to live up to his parents'

expectations as an adolescent and turned to guns and explosives as his

antidepressants.

From an early age, Kip seemed disconnected from his

parents and an older sister, who excelled at most everything they did.

He struggled to be accepted, struggled to achieve, struggled for

attention all his life -- but often came up short.

His parents, in turn, strove to steer Kip toward

positive pursuits. Yet though they were veteran educators, their son

posed problems even they were unsure how to handle.

They did what any reasonable parents would do --

giving Kip extra help with schoolwork when they recognized he had

learning difficulties, keeping rigid rules at home for a child who was

hyper and defiant, encouraging his involvement in sports and taking him

to a professional when they could not explain his persistent brooding.

But their good intentions were not enough, and, at

times, might have done more harm than good, some juvenile experts say.

Kip's schoolwork, mood and conduct slumped while his

fascination with explosives and guns steadily grew. Hoping to stem the

obsession, his father gave in to Kip's hunger for firearms -- disturbing

his wife and sending mixed messages to his son.

"When anyone is suffering from depression, with an

obsession for dangerous weapons, the last thing you'd want to do is make

a gun accessible," Portland psychologist Michael G. Conner says. "That's

a formula for disaster."

That disaster played out May 20.

Being the "teachers' " kid, Kip was sensitive to the

enormous shame his school expulsion would cause his parents. Kip might

have killed them to blunt their embarrassment, a last phone call with

his friends suggests.

When he was arrested and escorted out of school, he

hinted to a friend that he'd get even. The next day's rampage at

Thurston High might have been a final, desperate act of revenge -- and,

experts suggest, perhaps even a suicide mission.

For Bill and Faith Kinkel, the truth that their son

was dangerously disturbed might have finally been illuminated by the

flash of a gun.

"You'd think two trained educators could pick up on

Kip's problems. You'd think two teachers would know what to do," said

Tom Jacobson, a longtime family friend. "But sometimes you're too close

to the problem, especially when it's your own kid."

About 1:30 p.m., Bill Kinkel picked up Kip from the

Springfield police station, where he was taken after his arrest for

having a gun on school grounds.

They stopped at Bob's Burger Express on Main Street.

In a back booth, Bill did not eat; Kip had his usual -- a "Brute -- no

tomato, no onion and small fries."

Bill did not raise his voice but asked his son, "Why?"

Once home, he called Thurston High.

"Where do we go from here? What are the options?"

Bill Kinkel asked Robert Bushnell, his close friend and Kip's academic

counselor. "Obviously he can't return to Thurston. Where does he go to

school next year?"

They brainstormed. The Oregon National Guard's boot

camp or Mount Bachelor Academy in Bend were two ideas.

"Bill was looking ahead," Bushnell said.

Summer 1982 was coming to a close, and Bill Kinkel

had returned to Thurston High for teachers' training when Faith gave

birth to their second child.

Kipland Philip Kinkel was born Aug. 30, 1982, at

Sacred Heart Medical Center in Eugene. Bill Kinkel, then 43, and Faith,

41, were delighted to have a son. Their daughter, Kristin, was 5.

The Kinkels had settled comfortably into what they

considered their dream house -- an A-frame chalet nestled among tall

Douglas firs above the McKenzie River, 10 miles east of Springfield.

Faith Kinkel wrote relatives that she was living in "God's country."

Bill Kinkel planned to teach for another 10 years and retire.

Their friends kidded them about being older parents.

But they took it in stride.

"I admired them -- gosh, here Bill will have his 30

years in and be retired before his son even gets into high school,"

Marcie Bushnell, then a fellow Thurston teacher, had thought.

Kip had Faith's coloring -- auburn hair and blue eyes

-- and would acquire his father's energy and inquisitiveness.

Faith stopped teaching at Springfield High School to

stay home with her baby boy. She called Kip her "li'l angel" or "li'l

sweetheart" in letters to friends and relatives.

But the child nicknamed "Kipper" was a handful. From

the start, he was difficult -- insecure, extremely sensitive and hyper.

His early years were rife with temper tantrums and fits for attention.

"He was always hanging on to her," Bushnell recalled

of a time Kip was 3 or 4. "We were visiting and leaving his house one

day. We were saying goodbye on their deck, and Kip ran out to the deck

and clung to his mom's leg. She'd joke, 'Don't we give you enough

attention?' "

Kip cried easily and, in school, was bothered that he

was smaller than others his age. Because he was so sensitive about his

size, his parents enrolled him in karate at age 6 or 7, thinking it

would boost his self-esteem. He lasted only a few months.

Kip overheard his father talking on the phone one

floor below. Bill had called the Oregon National Guard to inquire about

its regimented boot camp.

Kip grabbed a .22-caliber semiautomatic Ruger rifle

he had secretly stashed. He sneaked up behind his dad, who was by the

kitchen counter, and fired one blast to the back of his head.

He removed a key from around his father's neck to

unlock a cabinet under his parents' bed. There shone his forbidden

treasures: a .22-caliber pistol Kip dragged his father to the bathroom

and covered him with a sheet.

In a family of overachievers, Kip did not measure up.

He began to struggle as early as first grade, when his parents' push to

keep him from veering off track began in earnest.

After discussions with teachers, they had Kip repeat

first grade at Walterville Elementary School, citing a lack of maturity

and slow emotional and physical development. They agonized about the

decision but grew convinced that Kip was not ready to move on.

Once they held him back, his parents wondered whether

they had acted too late. Maybe it would have been wiser to hold him back

in kindergarten, before he had formed friendships, they thought.

"I just remember him being mad," said Kasey Guianen,

Kip's childhood playmate. "His friends were all going up a grade. I told

him, 'But you'll be older, and you'll know more.' He didn't understand

why."

His parents thought Kip had an attention deficit

disorder and, possibly, dyslexia.

"He did this weird thing when he watched TV," said

Kasey, who often watched cartoons such as "Tailspin" and "Rescue

Rangers" with Kip. "He'd turn his head to the side and roll his eyes

back at the TV. I'd ask him, 'Doesn't it hurt your eyes?' I don't know

why he did it."

Faith and Bill helped Kip with his grade-school

homework. But Kip was easily distracted.

Playful and inquisitive, Kip could not sit still.

He'd spend hours outside in the woods behind his home -- scrounging

around in the dirt, catching frogs, putting salt on slugs to watch them

squirm. Often, he pretended he was a popular action figure, such as

Spiderman or a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle. Once, he thrust a stick into

a wasps' nest; the wasps swarmed him, leaving nasty welts on his back.

"He was always messing around," Kasey said. "He

always wanted to keep going and going. He'd never stop."

His parents laid down rigid rules for Kip -- limiting

television to one hour a night, restricting the type and amount of candy

he could eat, making sure he took a bath every night and was in bed at a

certain hour.

"Being that they were a little bit older, and being

teachers, they were probably a little more strict with him than a lot of

his friends' parents were. They were not as lenient," said Rose Weir,

Kasey's mom. "But if something was not permitted, he wanted it even

more. So when he came over to our house, he was a TV fiend. If you did

let him go, he'd just go overboard with it."

Faith spent more time with Kip than Bill did in the

early years and was more tolerant of his antics.

The first one out the door in the morning, Bill would

shout "T-T-F-N," for "Ta Ta For Now," Kasey recalled. "His dad would be

really busy -- going to play tennis, going sailing. Bill would do a lot

of his own things."

Said Weir: "Bill -- he would work with high school

kids throughout the day, and he'd come home to a much younger child. It

was a different scenario. Faith did have more patience with Kip than

Bill did."

Kip's parents rarely lost their tempers in public.

They tried to control Kip with "timeouts" or verbal reprimands. On one

family trip, Kip kept circling his bicycle through the campground,

irritating his parents.

"Kip, that's enough," they admonished him.

"But he was just bored," said Gary Guttormsen, a

close family friend who was on the trip. "Maybe they leaned on him a

little too hard. They were always afraid Kip was overbearing when they

were with their friends. Maybe they were forgetting he's a boy."

Tony McCown was surprised when Kip answered the phone

about 4:30 p.m. He figured Kip's parents would have suspended his phone

privileges.

Kip sounded despondent.

He told his friends he felt sick to his stomach. He

lied, saying his dad was at a bar. He wasn't sure how much trouble he'd

be in. He was worried about what his parents' friends would think. Most

were teachers or school administrators, and he knew news of his arrest

would spread like wildfire.

"It's over," Kip told McCown. "Everything's over."

Nick Hiaasen, whom McCown patched in on a conference

call, pressed Kip on why he risked buying a gun at school.

"Yeah, I know, I shouldn't have done it," Kip said.

"I don't know, I just wanted it. My parents will probably be so

embarrassed. Maybe we'll move away from everyone . . . to Alaska."

By the time Kip reached middle school, his sister had

graduated from high school, a top student and popular cheerleader who

went to the University of Oregon, where she cheered for the Ducks. She

would later earn a full scholarship to continue her cheerleading at

Hawaii Pacific University, with plans to follow in her parents' path,

teaching English as a second language.

By comparison, Kip had his first run-in with police

and was disruptive in school. He became a class clown, boasting about

how he liked to blow things up and hurt animals. He hung around

troublemakers, increasingly worrying his parents.

"Kip was a lot more laid-back -- whatever happens,

happens," Kasey said.

Kip's inadequacies became magnified in contrast with

his sister's and parents' accomplishments.

"Everyone in the family was always very ambitious and

hard-working," Marcie Bushnell said. "I think he realized there were

expectations -- everybody does their best. It was something the Kinkels

drummed into their kids -- it was almost like unspoken expectations."

Both parents were respected teachers, admired by

their colleagues and beloved by their students. Faith was now teaching

Spanish full time at Springfield High. She rose early to grade papers

and make it to school by 7:30 after her morning exercise. She'd help

students during her lunch break and after school.

Bill Kinkel was retired after 30 years at Thurston

High. An avid athlete and outdoorsman, he competed two days a week on

the Eugene Swim & Tennis Club courts, taught Spanish night classes at

Lane Community College four days a week and fit in travel.

For Kip, there was no escaping school. Most of his

parents' friends were Springfield teachers or school administrators, and

they often joined the family on holidays and trips.

Yet his parents rarely confided in them about their

most serious problems with Kip. To most of their adult friends, Kip

seemed respectful and polite, with typical teen-age troubles.

Kip's difficulties, though, emerged more visibly in

middle school.

Counselors thought he had an anger-management problem.

Some classmates said he'd throw fits if he thought someone in his gym

class was cheating or if someone hit him accidentally.

"He liked to do things he wasn't supposed to do,"

said Steve King, a classmate. "He'd bring firecrackers, stink bombs to

class. He and his friends were always talking about going out and

shooting squirrels."

Kip told friends he was taking the drug Ritalin in

middle school to control his temper. He resumed karate classes but

rarely used his karate moves on his friends. Yet one day in school,

disturbed when a classmate called him a name, Kip kicked the student in

the head. He was suspended for two or three days; the student was not

seriously injured.

"Kip came into the classroom crying," McCown said. "I

think he was worried about what his parents would do."

Another time, Kip told off his eighth-grade English

and social studies teacher. The teacher had difficulty controlling Kip

and his friends. She'd make them write and rewrite school rules, hoping

they would abide by them.

"Kip was abusive to his teacher. Bill told me just

what he said -- he told the teacher to go (expletive) herself," family

friend Jacobson said.

Concerned his son would fail or get kicked out of the

class, Bill intervened. He would cut out of tennis by 1 p.m. to pick up

Kip and home-school him during those periods.

"Bill was an educator and felt he could get Kip

further along with more cooperation from Kip," said Richard Bushnell,

Marcie's husband, who became Kip's counselor.

Kip wasn't pleased.

"He didn't like it, but it seemed to pay off," family

friend Guttormsen said.

After 2½ months of home-schooling, Kip returned to

school for the full day. By then, another teacher was assigned to the

class.

Later that school year, Kip had his first run-in with

police. On Jan. 4, 1997, he was charged with kicking a large rock -- 12

inches in diameter -- off a highway overpass in Bend with a classmate.

The rock struck the front of a car passing below.

"Faith would be real upset," said Springfield High

teacher Debbie Cullen. "She didn't understand why he'd do this."

She told fellow teacher Kathleen Petty she was

helping Kip memorize "The Lord's Prayer" -- she thought it would be good

for him.

Kip tuned in to the TV cartoon "South Park" about 7

p.m. In the episode, the character Kenny falls into a grave and gets

squashed by a tombstone. Kip's parents lay dead as he watched.

Later, in the quiet of his secluded home, Kip set

about rigging explosives in small nooks and crannies throughout the

house.

In a secret hiding place or "fort" in the woods

behind his house, Kip kept the materials he used to assemble the bombs:

clocks, bottles, batteries, ammonia, baking soda.

He wired what authorities called a "very

sophisticated" bomb with 1 pound of explosive charge in a crawl space

near the home's garage. Elsewhere, he left two crude pipe bombs, a hand

grenade, two 155 mm Howitzer canisters and a basketball-turned-bomb.

"They were still finding explosives there a week

later," family friend Berry Kessinger said. "There were bombs everywhere.

I'm surprised he didn't blow up the house."

As educators who spent decades handling difficult

students, Bill and Faith Kinkel were confident they could turn Kip

around. But ultimately they realized the strategies that worked so well

in their classrooms were failing with their son.

Exasperated, they sought professional help after Kip

finished middle school.

By June 1997, they were concerned about Kip's

melancholy, mopish behavior and wanted someone outside the school system

to evaluate him. On the advice of Richard Bushnell, Kip's parents took

their son to see Jeffrey L. Hicks, a Eugene psychologist.

Hicks counseled Kip in a tidy, one-room office filled

with stuffed animals. Kip was diagnosed with clinical depression and

began taking Prozac, an antidepressant.

It seemed to calm him. His parents were pleased with

Hicks.

"They liked him, and Kip seemed to like him," said

Cullen, the Springfield High teacher. "He worked well with Kip."

But, still, Kip's brooding perplexed his parents.

Bill, desperate for a better understanding of Kip's

problems, pulled one of his adult Spanish students aside on the last day

of class, June 3, 1997. He had just taught the class how to say "Enjoy

Yourself -- Diviertase bien," before recessing for the summer.

"His voice was low," recalled Cori Taggart, a

professional counselor. "He said he had just found out his son was

clinically depressed. 'What's going on?' he asked. 'I don't understand

what this is all about.' He seemed sort of confused."

Taggart told him that the condition was treatable but

that it was important that Kip get professional help. Bill nodded.

People with depression can become suicidal, Taggart added.

"He kind of made this face -- he kind of recoiled a

little bit, shaking his head. No, no, Kip wasn't suicidal. That's not

what's going on."

Kip's grandmother, Katie Kinkel, said Kip was

becoming a "loner." And despite the counseling and medication that

seemed to indicate he was improving, Kip's malaise on his 15th birthday

last August disturbed Faith.

"She didn't understand what was wrong with him,"

Cullen said. "She'd suggest things -- 'You want to do this?' No. 'You

want to do that?' No," Cullen said.

Petty, Faith's colleague, said, "She just felt very

sad about it, that he just wanted to be alone."

By October 1997, Kip stopped seeing the Eugene doctor

and apparently stopped taking Prozac. His parents told others they

thought Kip was doing better.

After a solitary night, Kip did not want to be late

to school.

He dressed in a long trench coat, filled a backpack

with clips of ammunition, tucked a pistol on either side of his

waistband and taped a knife to his ankle beneath his khaki pants.

He started his mom's Ford Explorer and drove off down

the winding, narrow roads near his home -- the very roads on which his

parents once feared he'd drive too fast and hurt himself, or others, now

that he had his instructional permit.

The older Kip got, the more fixated he became on

explosives and then guns.

Using a pocketknife his parents gave him one birthday,

he and Kasey cut branches and built forts in the woods. Intrigued by a

neighbor's BB gun, Kip wanted one of his own by age 10.

"Faith was just dead set against it," Weir said. "But

her resistance just fed his hunger for it. He was just one of those kids

if something was restricted, it became more desirable."

Kip's early attraction to action figures and BB guns

gradually grew into a passion for violent movies and a taste for heavy

metal music, such as Marilyn Manson and Nirvana, laced with lyrics of

death and destruction.

His parents continued to restrict his television and

video game privileges. But Kip would find a way around the limits, such

as watching television in the middle of the night when his parents were

asleep.

Kip used the Internet to obtain bomb-making recipes

and boasted to middle-school classmates about his hobby. He took books

such as "The Anarchists' Cookbook" to school. On an Internet account, he

cited his occupation: "Student surfing Web for info on how to build

bombs."

After his parents found a catalog for bomb-making

material Kip had obtained through the Internet, they cut his computer

use.

"Bill knew Kip had an interest in explosives,"

Jacobson said. "He described it as an obsession."

After explosives, Kip became enchanted with guns --

first reading about them and their various models, manufacturers,

bullets, bores and barrels. Soon, he badgered his parents to buy him

one.

As a child, if Kip showed an interest in something,

Faith generally tried to encourage it.

She drew the line with guns. Bill could not.

"In all the years they were married, Bill said this

was the one thing they disagreed on," recalled Rod Ruhoff, a tennis

partner.

Kip's pestering wore Bill down. He worried that Kip

would get his hands on a gun anyway, so he relented. It might also bring

father and son closer, he thought. They'd take a firearms safety course

together, and Bill would channel his son's interest positively.

Bill knew little about guns. He sought advice from

Denny Sperry during a break on the doubles court. If he was going to get

Kip a gun, Sperry suggested a bolt-action, single-shot .22-caliber

rifle. But Kip persuaded his dad to get him the more lethal weapon: a

.22-caliber semiautomatic rifle. Bill set parameters that Kip use the

rifle only under adult supervision.

Child psychologists, who have not evaluated Kip but

have worked with other troubled youths, said explosives and guns might

have given Kip a sense of power, control and a thrill that was missing

in his life.

"These kids never really fit in from the beginning,"

said Conner, the Portland psychologist. "They're aware of their

inadequacies. They feel misplaced, and they don't belong. They feel 'dead'

inside. This kid goes after anything that will get him out of it. It

could be drugs, sex, anything that stimulates or brings any feeling to

them. Kids will carry forbidden things around -- like weapons -- because

it's a thrill. It's their escape."

Kip parked the Ford Explorer on E Street, one block

from his high school. He walked down a dirt path, a shortcut to school.

He passed through a turnstile and calmly walked past

the tennis courts and into the back parking lot.

A school security camera caught him entering Thurston

High just before 8 a.m.

Bill Kinkel worried about Kip. He tried to get him

interested in football or motor biking or tennis. But Kip's mind was

elsewhere.

While waiting in the San Diego airport Dec. 14 for a

flight home after visiting a friend, Bill struck up a conversation with

a stranger, University of Oregon professor Dan Close -- an expert on

juvenile violence.

They talked about Ducks football, Thurston High,

Bill's interest in tennis, travel and teaching. Bill raved about his

daughter. Only when Close began to discuss a private issue in his life

did Bill Kinkel disclose his troubles.

"He said there were only two things in his life that

weren't great: One was that his wife was still teaching and not yet

retired; he couldn't take many of the trips he wanted to," Close said.

"And, second, he has this boy who was a very troubled child."

It was the first mention of Kip.

Bill spotted a thick book in Close's L.L. Bean carry-on

bag, titled "Clinical and Forensic Interviews of Children and Families."

Bill wanted to know the signs that precede juvenile violence.

Close rattled them off: dysfunctional family, child

abuse, drugs, a change in the child's peer group, special education

placement, criminal arrest, lack of parental supervision, parents'

minimizing a problem, cruelty to animals, access to guns.

"All of a sudden he just freaked," Close said. "He

said, 'We have a very good family, but I've got this son who's always

been very strong-willed, always wanted to get his way. We're educators,

but we've got this boy who's always been difficult.' "

Bill stood, his head down. He said Kip was not

interested in school, was obsessed with violence and had been arrested

for vandalism.

"I'm not a gun nut. But every kid around here has got

guns," Bill said in what Close described as a rehearsed way. "We decided

to let him have a gun. We lock the gun up and keep it secure. I wanted

control over the situation."

Close advised him to set limits. Bill rolled his eyes

and said, "We tried that stuff; it doesn't work with him."

"I believe the guy was tormented," Close said. "He

said he was a good kid, but he was scared to death of him. He was

worrying that he was capable of getting, really, really mad."

That weekend, an unprovoked Kip scrawled the word

"K-I-L-L" in whipped cream on a friend's driveway. Kip was one of four

friends Jeff Anderson invited to his house on his 15th birthday. Jeff's

mother banned Kip from returning to their home.

Kip pulled his favorite gun -- the .22-caliber

semiautomatic rifle -- from beneath his trench coat and opened fire in

the dark hallway of his school.

Two students dropped to the ground -- Ben Walker,

shot in the head, and Ryan Atteberry, shot in the face.

By now, Kip's fascination with explosives and guns

had infected his schoolwork at Thurston High.

In different classes, he wrote about killing people,

gave a detailed speech on how to make a bomb and learned to type as he

listened to one of his favorite heavy metal groups, Slayer, on headsets.

In Marian Smith's speech class, Kip gave a detailed

talk on "How to Make a Bomb," complete with a color-penciled drawing of

an explosive attached to a clock. In his literature class later that day,

he chuckled that he had gotten away with it.

Smith said she took appropriate action but refused to

specify what that was. Bushnell and Don Stone, school disciplinarian for

freshmen and sophomores, said they never were told. Stone's boss, Dick

Doyle, referred the question to the superintendent, who declined

comment.

Kip's father learned of the speech. Other teachers

heard about it during lunch in the faculty lounge.

"Bill told me just in passing -- 'Guess what Kip did

this time? Yeah, Kip even did a report in class on how to make a bomb.'

He didn't let on it was a major deal," Jacobson said. "Through the whole

thing, I don't think they realized how dangerous he was."

Kip's violent prose continued. In Kevin Rowan's

literature class, Kip filled his daily journal assignments with guns,

bombs and knives.

"He'd write, 'If I was the ruler of this country, I'd

go and bomb . . .' and sometimes it would get too graphic," classmate

Cassidy Rhoden recalled. Or he'd write about "being Godzilla and walking

down the street and killing everyone." Once he wrote about hurting a

classmate who got on his nerves.

Rowan often interrupted him as he read his work aloud.

"Mr. Rowan would sometimes cut in, 'That's rude --

you don't need to be saying things like that,' " classmate Tesa Manka

said. "Mr. Rowan would have him rewrite it more politely."

Kip would slam his books down and angrily storm out.

Bill, who was friendly with Rowan, was apparently

informed. Again, Bushnell and Stone said they were unaware of the

writings, but Bushnell wishes he had been told.

"If I had been aware of it, I probably would have

gone to Bill and Faith and done an assessment as to where we were with

Jeff Hicks, and talked directly to Jeff Hicks. Obviously, things didn't

come together exactly right," Bushnell said.

Although Bushnell was close to the Kinkels, Bill

never told him that he had gotten Kip a gun. It was mostly Bill's tennis

pals who knew.

"Bill never included the right people in that,"

Bushnell said. "I don't know whether it was Bill's pride . . . I wish

Bill had come to me."

Kip stoically continued down the hallway to the

school cafeteria.

Nickolauson, hit multiple times, died within minutes.

The cafeteria erupted in chaos.

Several students tackled Kip as he tried to reach

into his backpack for another clip of ammunition.

He blasted one more shot from his 9 mm Glock before

he was wrestled to the ground.

"Just shoot me," he said.

The rifle Bill Kinkel got Kip only fanned Kip's

desire for more firearms. Despite professor Close's words of caution,

Bill gave in to Kip's desire for a handgun earlier this year.

At the tennis club in January, Bill "asked me if I

was familiar with the 'Glock,' " Ruhoff said. "It cost more than $400."

Kip had earned money doing odd jobs. Bill decided he

was going to own the gun and keep it until Kip was old enough and could

be responsible with it.

But by early February, shortly after the gun got into

Kip's hands, he broke the bargain. Neighbors heard him firing in the

woods. Bill confronted Kip, who acknowledged he had been shooting. Bill

seized the weapon. Exasperated, he wrapped the gun in a towel, took it

to the tennis club and put it in his locker.

Ultimately, Bill had a gun-lock cabinet placed under

his and Faith's bed, and he wore the key around his neck. He no longer

trusted Kip.

In late April or early May, Kip wound up in more

trouble. He and his friends were at McCown's house and scooted out for a

midnight prank -- toilet-papering a house.

Bill grounded his son through the summer -- cutting

off his phone, television and computer privileges, and preventing him

from going on sleepovers. His dad, growing more distrustful of his son,

went through Kip's room and found a padlocked trunk he had hidden. He

cut the lock. Inside were more guns -- a sawed-off shotgun and

.22-caliber pistol. Friends said Kip had bought them from students --

one before getting on the school bus one day.

The confiscation of his guns did not deter Kip from

his obsession. "It was something he felt he couldn't live without,"

Conner suggests.

On May 19, classmate Korey Ewert arranged to sell Kip

a stolen gun. Ewert had snatched the gun from the home of Thurston High

student Aaron Keeney. He had entered the Keeney home through a back

door, knew where to look and walked off with a .32-caliber pistol,

Ewert's uncle said.

The next morning, Kip brought $110 in cash to school

-- three weeks' worth of savings, partly earned staining his parents'

deck at $5 an hour. Ewert handed Kip the gun in a paper sack; Kip placed

it in a lower corner of his locker.

Aaron's father, Scott Keeney, noticed his pistol

missing and called the school early May 20. Kip was pulled out of his

second-period study hall. As administrators searched his locker, he

waited in the small office of Stone, school disciplinarian and football

coach.

"Coach, what's going to happen if I have the gun?"

Kip asked. Stone told him the school had no tolerance for guns; he would

not be able to return to school for a year.

Kip dropped his head and mumbled, "Sorry, coach."

"He looked up one time like he was ready to cry but

sucked it in," Stone said. A police officer took Kip into the hallway,

searched him, cuffed him and walked him to a cruiser parked in front of

the school.

As Kip and Korey were escorted out of school, Kip

whispered to Korey, "They'll get theirs."

Massmurder.zyns.com |