United States Court of Appeals

For the Eighth Circuit

No. 96-2563EM

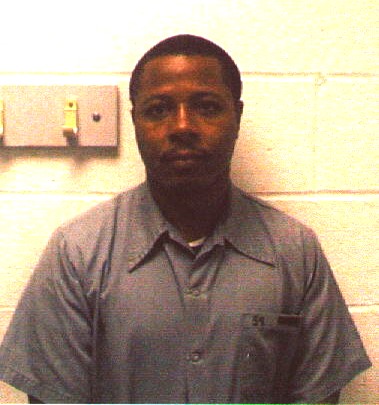

Bruce

Kilgore, Appellant,

v.

Michael Bowersox and Jeremiah W. Nixon, Appellees.

Submitted: June 9, 1997

Filed: September 8, 1997

RICHARD S. ARNOLD,

Chief Judge.

Bruce Kilgore was convicted of first-degree

murder and sentenced to death. After the Missouri state courts

affirmed his conviction and denied him post-conviction relief,

Kilgore filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus under 28 U.S.C.

� 2254 in the District Court.(1) The District Court denied the

petition, and we affirm.

I.

Bruce Kilgore was convicted of first-degree murder for the death of

Marilyn Wilkins. The facts surrounding her kidnapping and

murder are laid out in detail in the District Court's opinion, and

we repeat only a few here, for the sake of clarity.

Bruce Kilgore and Willie Luckett together kidnapped Marilyn Wilkins

as she left her job working at a restaurant where Luckett formerly

worked. Luckett's belief that Wilkins was responsible for his

firing led to the plan to kidnap her. Because she recognized

Luckett, Luckett told her she would have to be killed. She was

then stabbed several times, and died after her throat was cut.

Renee Dickerson, Luckett's girlfriend, knew of

the kidnapping plan, and saw the two men after the murder.

Lessie Vance, a cousin of Luckett's, accompanied the two men on the

day following the murder on trips to pawn shops, where they sold

Wilkins's jewelry. Kilgore was eventually arrested, and made

statements to the police about the murder and where evidence could

be found. After a jury trial, Kilgore was convicted of first-degree

murder, and sentenced by the jury to death and to two consecutive

life sentences for first-degree robbery and kidnapping.

The Missouri Supreme Court affirmed Kilgore's conviction on direct

appeal, and approved his sentence after a proportionality review.

State v. Kilgore, 771 S.W.2d 57 (Mo.) (en banc), cert. denied, 493

U.S. 874 (1989).

Kilgore filed for post-conviction

relief under Missouri Supreme Court Rule 29.15, but was denied

relief because his motion was untimely and unverified. After a

hearing, the Missouri Supreme Court affirmed the denial of post-conviction

relief. Kilgore v. State, 791 S.W.2d 393 (Mo. 1990) (en banc).

Kilgore then sought a writ of habeas corpus under Missouri Supreme

Court Rule 91. The Supreme Court denied Kilgore's petition,

because all the grounds for relief stated therein had been rejected

either on direct appeal or as part of the Rule 29.15 proceeding, or

were procedurally barred because Kilgore had provided no sufficient

reason to excuse his failure to present them in those earlier

proceedings.

No other state-court remedy then

remained. Kilgore filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus

in the District Court under 28 U.S.C. � 2254, which was denied.

Kilgore now appeals.

II.

Kilgore offers several arguments for reversal, and we address them

seriatim. The State points out throughout its brief that

Kilgore should be procedurally barred from raising many of his

claims. Because we reject the claims on their merits, we do

not discuss the procedural-bar issues. See Lashley v.

Armontrout, 957 F.2d 1495, 1499 (8th Cir. 1992), vacated on other

grounds, 993 F.2d 642 (8th Cir. 1993), rev'd on other grounds, 507

U.S. 272 (1993).

A. Alleged Prosecutorial

Misconduct

Kilgore argues that prosecutorial

misconduct prejudiced his case. The misconduct he alleges

centered primarily around one of the state's witnesses, Renee

Dickerson. Kilgore believes the prosecution withheld vital

information about Dickerson and about another witness, Lessie Vance.

1. Notification of Dickerson's Testimony

Kilgore's counsel asked to depose Dickerson months before trial.

The prosecution responded that she would not be called as a witness,

and that she in fact had been charged with hindering prosecution.

Kilgore's attorney accordingly did not depose Dickerson. Later,

once the trial was under way, the prosecution endorsed Dickerson as

a witness, just before she was to testify in the penalty phase.

Kilgore argues that the prosecution suppressed valuable evidence and

impermissibly surprised Kilgore with Dickerson's testimony, in

violation of Missouri court rules and the Constitution.

The District Court found that the prosecution's

conduct was explained by Dickerson's decision, after trial had begun,

that she was willing to testify. Defense counsel did not have

time to depose Dickerson, but did interview her before she testified,

and, according to the Missouri Supreme Court, learned of the content

of Dickerson's upcoming testimony. See State v. Kilgore, 771

S.W.2d at 65.

Before trial, Dickerson had not been expected to

testify. The prosecution assumed, reasonably, that she would invoke

the privilege against self-incrimination if called as a witness.

After the trial began, Dickerson pleaded guilty to a criminal charge

in connection with the murder, thus eliminating this obstacle to her

testimony.

Dickerson's testimony was the only

evidence suggesting that Kilgore, rather than Luckett, actually

wielded the knife. Dickerson testified that Kilgore admitted to her

that he killed Wilkins. This was doubtless damaging testimony,

and may very well have been a major factor in the jury's decision to

sentence Kilgore to death. The question, however, is not whether the

evidence was damaging to the defense, but whether the defendant was

deprived of a fair trial. The defense's lack of deposition

testimony meant that it had less information with which to

impeach Dickerson.

Prior to trial, Dickerson had spoken with

authorities about the killing on three separate occasions, without

ever once mentioning that she heard Kilgore confess. One can

presume she would have made the same omission, under oath, in a

deposition, and the defense would have had one more prior

inconsistent statement of Dickerson's to bring out at trial.

The standard for evaluating the failure to provide information to

the defense is whether a reasonable probability exists that, had the

information been disclosed to the defense, the result of the

proceeding would have been different. United States v. Bagley,

473 U.S. 667, 682 (1985).

The District Court held that, because defense

counsel had ample other information and prior inconsistent

statements with which to impeach Dickerson, and with which he did

impeach Dickerson, there was no reasonable probability the outcome

would have been different, and the Bagley standard was not met.

The defense brought out that Dickerson had, on

three occasions, failed to mention Kilgore's admission when speaking

with authorities; that she claimed to have heard Kilgore's admission

right after being awakened; and that she was Luckett's girlfriend

and might be biased on that account. We see no reason to

disagree with the District Court's decision that deposition

testimony of Dickerson would not have provided the defense with

significantly more impeachment material than it had anyway, and that

the additional information would not have changed the outcome of the

trial.

2. Plea Bargain

Kilgore also argues that the prosecution failed to disclose that

Dickerson's testimony was part of a plea bargain between her and the

prosecution. The District Court found that Kilgore presented

no evidence that such an agreement existed. The Missouri

Supreme Court refers to "the plea-bargain disposition of Dickerson's

own criminal case," 771 S.W.2d at 67, but the record nowhere shows

what the bargain was. It is therefore impossible to say what

the effect of cross-examination on the subject of the plea bargain

would have been, so this argument cannot succeed.

3. Change of Theory at Penalty Phase

The prosecution's theory during the guilt phase

was that Willie Luckett killed Marilyn Wilkins, and that Kilgore was

guilty of aiding and abetting Luckett. After Dickerson

testified that Kilgore admitted doing the killing himself, the

prosecution changed its theory, and during the penalty phase argued

that Kilgore was the killer. Kilgore argues that this

change in theories violated his constitutional rights. The

District Court rejected his argument.

The Court attributed the surprising nature of the

change to the unusual "confluence of events" during Kilgore's trial,

rather than to prosecutorial misconduct. We see no error in

the District Court's analysis. The prosecution, upon learning

for the first time (from Dickerson) that Kilgore had been the killer

(or had admitted the killing) could hardly be expected not to use

the information. At this point, Kilgore had already been

convicted of capital murder. The change in theory might, in

fact, have helped Kilgore, by giving the jury some reason to suspect

the soundness of the prosecution's evidence.

4.

Tape Recordings of Lessie Vance

Kilgore

asserts that the prosecution committed another Bagley violation in

failing to disclose certain tape-recorded statements of Lessie Vance,

which the defense would have been able to use in impeaching Vance's

credibility. Vance testified at trial that he, Kilgore, and

Luckett pawned Wilkins's jewelry the day after she was killed.

The tape-recordings apparently were of an early conversation between

Vance and the police, in which Vance provided an alternative

explanation of why he had Wilkins's jewelry.

The

District Court held that there was no Bagley prejudice in the non-disclosure

of the tapes, because Vance testified repeatedly at trial that he

had lied during that first meeting with the police. The

defense knew about the statements themselves, and would have been in

no better position to impeach Vance if it had had the tapes.

We concur in the District Court's conclusion.

B. Jury Instruction

Kilgore also

challenges one of the jury instructions given in his case as failing

to require the jury to find that he had deliberated in order to

convict him of first-degree murder. It is unclear whether

Kilgore intends us to read this argument as if the instruction

itself worked a constitutional violation, or as an example of

ineffective assistance of counsel. It was argued to the

District Court as an ineffective-assistance-of-appellate-counsel

claim, and we too will treat it as such.

This

claim was presented to the District Court for the first time in a

Rule 59(e) motion. Because Kilgore showed no good reason to

excuse his failure to raise the claim in his original habeas

petition, the District Court correctly dismissed the claim as

untimely. It went on, however, to reject the argument on its

merits as well.

There are several problems with Kilgore's

assertion that his appellate counsel was ineffective for failing to

argue this purported instructional error. First, the cases

upon which Kilgore principally relies to reveal the error, and which

he argues show the ineffectiveness of his appellate lawyer, were

decided after Kilgore's direct appeal had already been affirmed by

the Missouri Supreme Court. See State v. Ervin, 835 S.W.2d

905 (Mo. 1992) (en banc), cert. denied, 507 U.S. 954 (1993); State

v. O'Brien, 857 S.W.2d 212 (Mo. 1993) (en banc); State v. Ferguson,

887 S.W.2d 585 (Mo. 1994) (en banc).

Second, while the Missouri state courts have

refined their jury instructions so that they define more carefully

Missouri's definition of its own "deliberation" requirement, there

is no due-process violation in the instruction as it was given to

Kilgore's jury. The instruction required the jury to find that

Kilgore acted with cool reflection, which is the precise definition

of deliberation under state law. We affirm the District Court

on this point as well.

C. Aggravating-Circumstance

Instruction

The jury found four statutory

aggravating circumstances, plus two others based on prior

convictions, when it sentenced Kilgore. Kilgore now argues that the

four statutory aggravating-circumstance instructions were

constitutionally flawed. We do not agree.

Kilgore argues that two of the aggravating circumstances, as

submitted to the jury, are unconstitutionally vague and overbroad.

One of the aggravating circumstances the jury

found was that the killing "involved torture or depravity of mind

and as a result thereof was outrageously or wantonly vile, horrible,

or inhuman." Kilgore v. State, 771 S.W.2d at 68. We have

rejected the argument that this instruction is vague. In Smith

v. Armontrout, 888 F.2d 530, 538 (8th Cir. 1989), we held that a

finding of torture could show a properly limited construction of the

"vile, horrible, or inhuman" description, such that jurors could

reasonably designate some murders as worse than others for purposes

of imposing the death penalty. (The Missouri Supreme Court had

adopted this limiting construction before the trial in this case.)

The instruction was supported by substantial

evidence, since there is evidence that Wilkins was kidnapped, driven

around face-down in a car, told she was going to be killed,

and had wounds consistent with attempting to fight off her attacker.

These facts support a finding of both physical and psychological

torture, and the instruction as applied in this case was neither

vague nor overbroad.

The second aggravating

circumstance Kilgore challenges for overbreadth is that the killing

was committed "for the purpose of avoiding, interfering with, or

preventing a lawful arrest." Kilgore v. State, 771 S.W.2d at 68.

The District Court held that this aggravating circumstance provided

the jury with a means rationally to distinguish murderers who should

receive the death penalty from those who should not. Accord,

Mathenia v. Delo, 975 F.2d 444, 449-50 (8th Cir. 1992), cert. denied,

507 U.S. 995 (1993). We agree.

Kilgore also

argues that two of the aggravating circumstances submitted to the

jury were duplicative. The jury found both that Kilgore

committed the killing for the purpose of receiving money or some

other thing of monetary value, and that Kilgore committed the crime

during the perpetration of a robbery and kidnapping. As the

Missouri Supreme Court has noted, the two circumstances are related,

but distinct, because they concern different facets of criminal

activity. State v. Jones, 749 S.W.2d 356, 365 (Mo.) (en banc),

cert. denied, 488 U.S. 871 (1988).

Even if that distinction were insufficient, and

only one of the aggravating circumstances were allowed to stand, the

error would still be harmless. Four aggravating circumstances

would remain. By the same logic, even if Kilgore were to

prevail in all his arguments, he would only eliminate three, or

possibly four, of the six aggravating circumstances cited by the

jury. In Missouri, only one aggravating circumstance is

required to support a death sentence. Schlup v. State, 758 S.W.2d

715, 716 (Mo. 1988) (en banc). Missouri is a "non-weighing"

state. The District Court correctly rejected Kilgore's

aggravating-circumstance claims.

D.

Mitigating-Circumstance Instruction

Kilgore

argues that the mitigating-circumstance instruction given his jury

was phrased so as to limit impermissibly the jury's discretion to

find that there were mitigating circumstances which outweighed the

aggravating circumstances of the crime. The instruction, he

argues, violates Mills v. Maryland, 486 U.S. 367 (1988), and McKoy

v. North Carolina, 494 U.S. 433 (1990). Kilgore's argument is

foreclosed by our decision in Reese v. Delo, 94 F.3d 1177, 1186 (8th

Cir. 1996), cert. denied, 117 S. Ct. 2421 (1997).

In that case, the petitioner made a virtually

identical argument to the one Kilgore now advances, about the same

wording in Missouri's mitigating-circumstance instruction. We

reject Kilgore's argument for the same reasons.

E. Voir Dire

Kilgore alleges that the

voir dire procedures employed in the selection of his jury were

unconstitutional. Kilgore, who is African-American, was

convicted by an all-white jury, and asserts that potential African-American

jurors were struck from the venire in violation of Batson v.

Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986). The prosecution used five of its

nine peremptory strikes on African-Americans. The Missouri

Supreme Court, and the District Court in turn, held that the

prosecution struck those African-American veniremembers for race-neutral

reasons. We agree.

Four of the five African-American

prospective jurors who were struck had had significant contact with

the criminal-justice system. Kilgore argues that there were

white jurors who had had similar contact, but were not struck.

The two groups are not identical, however; the four African-American

potential jurors also gave what the prosecution considered "weak"

or equivocal answers when asked about their willingness to impose

the death penalty.

The white potential jurors who had had contact

with the criminal justice system were not similarly "death-scrupled."

The fifth African-American juror who was struck said she had seen

the victim's son on television and in public. The son was

scheduled to testify for the state. The prosecution struck her

out of concern that her prior experience of one of the state's

witnesses might unfavorably affect her perception of that witness's

testimony.

The District Court held that since the

prosecution offered acceptable race-neutral reasons for exercising

its peremptory strikes of the five African-American potential jurors,

there is no Batson violation. Again, we agree with that Court.

F. Trial Court Errors

Kilgore claims

the trial court committed several errors which violated his

constitutional rights.

1. Coerced

Confession

Kilgore asserts that the trial

court erred in admitting into evidence several statements he made to

the police. He alleges he was beaten and threatened by police

officers, and that the statements he made were therefore physically

and mentally coerced.

The District Court was unconvinced by this

allegation, however, because Kilgore never produced statements from

any of the witnesses he claims can corroborate his assertions,

including his mother and aunt, both of whom testified for him during

the penalty phase of his trial without mentioning beatings or the

noticeable injuries Kilgore asserts he received during the beatings.

Additionally, four police officers testified that Kilgore was not

beaten or threatened, but was in fact notified of his Miranda rights

at the time of his arrest and at several times afterward. We

see no error in the District Court's conclusion.

2. Lack of Jurisdiction

Kilgore

argues that the information in lieu of indictment did not allege

facts sufficient to base jurisdiction in the City of St. Louis.

The information alleged that the killing took place in St. Louis

County, outside the jurisdiction of the City. Before the

District Court, Kilgore alleged that no element of the crime charged

took place within the City's jurisdiction.

Kilgore was charged with multiple crimes, however:

first-degree murder, first-degree robbery, and kidnapping. The

information asserted the City had jurisdiction because Wilkins was

abducted in the City. Federal-court review of the sufficiency of an

information is limited to whether it was constitutionally deficient;

whether it comported with requirements of state law is a question

for state courts. Johnson v. Trickey, 882 F.2d 316, 320 (8th

Cir. 1989).

The inquiry for our Court, therefore, is not

whether the information communicated the basis of jurisdiction in

compliance with state law, but rather whether it gave Kilgore

adequate notice of the potential charges against him so that he

could prepare to contest those charges. Blair v. Armontrout,

916 F.2d 1310, 1329 (8th Cir. 1990), cert. denied, 502 U.S. 825

(1991). The District Court held that since the information

provided Kilgore with sufficient notice, it met the requirements of

due process. We agree with that determination.

3. Trial Judge's Report

The trial

judge, in accordance with Mo. Rev. Stat. � 565.035, submitted a

report about Kilgore's trial to the Missouri Supreme Court for

consideration in its proportionality review of Kilgore's sentence.

Kilgore argues that the statute requiring submission of the report

is unconstitutional because it denies convicted defendants their

right to confrontation. This claim has no merit. The trial

judge was not a witness against Kilgore.

In addition, subsection 4 of that statute gives

defendants, and the state, the right to submit briefs and to present

oral argument about the proportionality of the sentence to the

Supreme Court. Mo. Rev. Stat. � 565.035.4. It is

clear from that court's opinion that it considered several arguments

advanced by Kilgore in arriving at its decision that the death

sentence was proportionate in his case. Kilgore v. State, 771 S.W.2d

at 68-70. Kilgore's right to confrontation was not

violated.

4. Victim's Good Character

The District Court dismissed this claim because petitioner did not

specify what evidence of the victim's good character was introduced.

Kilgore includes no more information in his brief to this Court.

We likewise reject the claim.

G. 29.15

Proceedings

Kilgore alleges that the Missouri

state courts deprived him of his constitutional rights in

arbitrarily applying a procedural-bar rule in Kilgore's 29.15

proceedings. He argues first that the 30-day filing deadline

contained in Rule 29.15 is unconstitutional because it is too short.

This cannot be the case; states are not required by the Constitution

to provide post-conviction procedures like that of Rule 29.15, and

the time limit is not, at least in the abstract (which is all

petitioner argues), unreasonably short.

Kilgore

also alleges that the state courts deprived him of his

constitutional right to equal protection by refusing to consider his

29.15 motion. The trial judge dismissed Kilgore's 29.15 motion

because it was untimely and unverified. Kilgore v. State, 791

S.W.2d at 393-94. Kilgore appealed the dismissal, and the

Missouri Supreme Court affirmed. Id.

He now argues that other movants under the Rule

have been treated more favorably, and that the strict application of

the Rule's requirements to him denied him equal protection. He

cites three cases to support that contention, but none of those

cases concerns a movant similarly situated to Kilgore. See

State v. Ervin, 835 S.W.2d at 927-28; State v. Hamilton, 791 S.W.2d

789, 797-98 (Mo. 1990), cert. denied, 513 U.S. 1085 (1995);

Reuscher v. State, 887 S.W.2d 588, 590-91 (Mo. 1994) (en banc),

cert. denied, 514 U.S. 1119 (1995). We see no evidence that

Kilgore received unequal or arbitrary treatment in his 29.15

proceedings.

H. Ineffective Assistance of

Counsel

Kilgore alleges that his counsel

rendered constitutionally ineffective assistance in several respects.

On none of those occasions did Kilgore's counsel fall below the

standard enunciated in Strickland v. Washington, 466 U.S. 668, 694

(1984). We reject this claim as well.

1.

Hearsay

Kilgore charges that his counsel was

ineffective for failing to object when Renee Dickerson

testified that Willie Luckett was remorseful about the killing.

Kilgore argues that Dickerson's statements were inadmissible hearsay.

His counsel did, however, make a hearsay objection when Dickerson

was asked whether Luckett had said anything to express remorse, and

the trial court sustained defense counsel's objection.

The prosecution then rephrased the question to ask what Dickerson

herself observed. Not only did defense counsel object to

questions calling for hearsay, those objections were sustained.

We see no error indicating deficient performance by Kilgore's

counsel in this regard.

2. Failure to

Request Continuance

The second error Kilgore

argues his counsel made was failing to request a continuance when

Renee Dickerson was endorsed as a witness. Kilgore's trial

counsel objected to Dickerson's testimony on the basis of surprise

and subjected her to thorough cross-examination. Again, we see

no indication that the outcome of the trial would have been

different had counsel made such a request. Kilgore does not indicate

what favorable evidence could have been developed if a continuance

had been granted.

3. Coerced

Statements

Kilgore argues that his counsel

failed to investigate adequately the "coerced statement," and

presumably the coercion itself. The District Court found that

counsel did file a motion to suppress the statement, which was

denied by the trial judge. Kilgore has not come forward with any

evidence of what his lawyer would have discovered in a more

extensive investigation. As is noted above, Kilgore has

offered no statements by witnesses (other than himself) to the

alleged police coercion or to Kilgore's resulting injuries.

Two of those witnesses are his mother and aunt,

who testified during the penalty phase of the trial, but did not

mention any coercion or resulting physical injury. We again

have no evidence of how the outcome of the proceedings might have

been different had counsel made different choices. Accordingly,

we agree with the District Court's conclusion that there was no

Strickland prejudice.

4. Individual

Voir Dire

Kilgore argues his counsel should

have requested individual voir dire. The District Court

rejected this claim because there is no indication in the record

that group questioning of potential jurors was insufficient, or that

the composition of the jury would have been different had jurors

been questioned individually. Again, there is no showing of

Strickland prejudice, and we affirm.

5.

Lesser-Included-Offense Instruction

The trial

court instructed Kilgore's jury on two offenses: first-degree

(capital) murder and second-degree murder. Kilgore argues that

the failure to instruct the jury on the additional offense of second-degree

felony murder violated his constitutional rights under Beck v.

Alabama, 447 U.S. 625 (1980).

As an initial matter, it is difficult to discern

from Kilgore's brief whether the claim he asserts is a free-standing

Beck claim, or a claim that his lawyer's failure to attempt to cure

the alleged Beck violation at trial constitutes ineffective

assistance of counsel. Kilgore includes this claim in the

section of his brief concerning ineffective assistance, but does not

address his lawyer's performance as such.

Instead, he argues that the failure to instruct

the jury on second-degree felony murder violated his rights to due

process, equal protection, and freedom from cruel and unusual

punishment. Since the issue was presented to the District

Court as an ineffective-assistance claim, and the District Court

decided it as such, we too will treat it as an

ineffective-assistance claim.

Kilgore argues that

his trial counsel should have requested a second-degree felony-murder

instruction. The District Court held that Kilgore could not

show prejudice sufficient to satisfy Strickland. The District

Court reasoned, on the basis of Missouri state courts' treatment of

the issue, that since the jury had the option of convicting

Kilgore of first-degree murder, second-degree murder, or nothing,

and convicted him of first-degree murder, there was no harm in

failing to give the second-degree felony murder instruction.

The jury had the option of convicting Kilgore of

a lesser offense, and did not. They must have found, the

reasoning continues, evidence of the deliberation which separates

first-degree from second-degree murder. Therefore, the jury

never would have convicted him of any lesser offense, and the

absence of the instruction was harmless. See State v. Petary,

781 S.W.2d 534, 544 (Mo. 1989) (en banc), vacated on other grounds,

494 U.S. 1075, affirmed on remand, 790 S.W.2d 243, cert. denied,

498 U.S. 973 (1990).

This analysis might not hold

true if the lesser-included-offense instruction did not make sense;

a crime which carried a drastically lesser sentence would leave the

jury with something dangerously close to the all-or-nothing choice

prohibited by Beck.

In this case, however, the jury was given a

reasonable second option, and one which was supported by the facts.

Kilgore argues that when a defendant is tried for an offense which

carries the death penalty, the trial court must submit to the jury

all lesser included offenses supported by the record. This is

not the law. In Schad v. Arizona, 501 U.S. 624, 645-48 (1991),

the Supreme Court held that Beck did not require a trial court to

instruct on all possible lesser-included offenses. See also

Reeves v. Hopkins, 102 F.3d 977 (8th Cir. 1996); Six v. Delo, 94

F.3d 469, 478 (8th Cir. 1996), cert. denied, 117 S. Ct. 2418 (1997).

In Schad, the trial court instructed the jury on

capital murder and on second-degree murder. Schad argued that

Beck required that a robbery instruction also be given. The

Supreme Court rejected the argument, holding that "[t]his central

concern of Beck simply is not implicated . . . for petitioner's jury

was not presented with an all-or-nothing choice." Id. at 647.

We are satisfied, in this case, that the jury had a real choice, and

that Kilgore cannot show Strickland prejudice. We agree with

the District Court's analysis.

6. Other

Arguments

Kilgore's brief lists several other

reasons he believes his counsel rendered constitutionally deficient

performance. Appellant's Br. 35. He has presented arguments,

beyond the mere listing of the alleged error, to this Court

about only a few, which are addressed above. The District

Court addressed and rejected each of his other arguments, and

Kilgore has offered us no reason why the District Court erred in its

decision.

In each instance, the District Court held that at

least one of the components of the Strickland standard was not met.

We see nothing in the record before us to cast doubt upon the

District Court's conclusions, and for the sake of brevity will not

repeat that conclusion over and over again here.

I. Proportionality Review

Kilgore asserts that the Missouri Supreme Court's review of the

proportionality of his sentence violated his right to due process.

The Missouri legislature mandates such a review of all cases where

the death sentence is imposed in Missouri courts. Mo. Rev.

Stat. � 565.035. While the review is not mandated by the

federal Constitution, once in place it must be conducted

consistently with the Due Process Clause.

Kilgore argues that the Missouri Supreme Court

conducts arbitrary review of prior cases and sentences, intent on "automatically

affirm[ing] death sentences" rather than on meaningful comparison,

and thereby fails to meet the requirements of the Missouri statute.

Appellant's Br. 48. He also argues that the state courts do

not maintain an adequate database of cases since May 1977 where

death sentences or life sentences without parole were imposed, and

that the inadequacy of the database further undermines meaningful

proportionality review.

We have considered and rejected this argument

before. The State Supreme Court in this case did conduct a

comparison of Kilgore's case with similar cases, and concluded that,

against the backdrop of other Missouri cases, the death penalty was

not disproportionate to the crime of which Kilgore was convicted.

State v. Kilgore, 771 S.W.2d at 69-70; id. at 70 (Blackmar, J.,

concurring). We will not, in such a case, look behind the

Missouri Supreme Court's conclusion or consider whether that court

misinterpreted the Missouri statute requiring proportionality review.

Bannister v. Delo, 100 F.3d 610, 627 (8th Cir. 1996), cert. denied,

117 S. Ct. 2526 (1997). We see no constitutional error.