It was later revealed by police that he had drunk an excessive amount of wine and hard liquors that morning, along with two ounces of absinthe. However, due to the moral panic against absinthe in Europe at that time, his murders were blamed solely on the influence of absinthe, leading to a moral panic and a petition to ban absinthe in Switzerland shortly after the murders.

The petition received 82,000 signatures and absinthe was banned in Vaud shortly thereafter. A 1908 constitutional referendum led to absinthe being banned in all of Switzerland, and absinthe was banned in most European countries (and the United States) before the outbreak of World War I.

The murders

During lunch on August 28, 1905, Lanfray consumed seven glasses of wine, six glasses of cognac, one coffee laced with brandy, two crème de menthes, and two glasses of absinthe after eating a sandwich. He returned home drunk with his father, and drank another coffee with brandy.

He then got into an argument with his wife, and asked his wife to polish his shoes for him. When she refused, Lanfray retrieved a rifle and shot her once in the head, killing her instantly, causing his father to flee.

His four-year-old daughter, Rose, heard the noise and ran into the room, where Lanfray shot and killed her and his two-year-old daughter, Blanche. He then shot himself in the jaw and carried Blanche's body to the garden, where he collapsed.

He was discovered minutes later by police after his father notified the police. After being taken to a hospital, Lanfray eventually recovered and was put on trial for murder.

Trial and death

The trial started on February 23, 1906 and ended that same day. It was argued by his attorneys that the two ounces of absinthe he consumed prior to the murders were solely to blame for his actions; Dr. Albert Mahaim, a leading Swiss psychologist, testified that Lanfray suffered from "a classic case of absinthe madness".

However, the prosecuter, Alfred Obrist, argued that the two ounces of absinthe he had ingested were minor in relation to the large amounts of other alcoholic beverages he had consumed that day.

Lanfray was eventually found guilty on all three counts of murder and received thirty years' imprionment. Due to his intoxicated state at the time of the murders, he did not face capital punishment.

Three days after the trial, on February 26, 1906, Lanfray committed suicide by hanging in his prison cell.

Public reaction

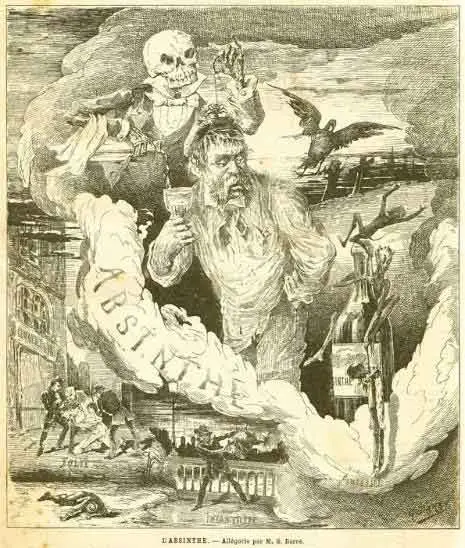

The Lanfray case received an astonishing amount of coverage, especially by Europe's temperance movement. It set off a moral panic against absinthe in Switzerland and other countries. A petition to ban absinthe in Switzerland received 82,000 signatures, and on May 15, 1906, the Vaud legislature voted to ban absinthe.

Following pressure from cafe owners and absinthe manufacturers, a referendum to reverse this decision was launched, but failed 23,062 to 16,025. On February 2, 1907, the Grand Conseil voted to ban the retail sale of absinthe, including its imitations.

Finally, on July 5, 1908, Article 32 to the Swiss Constitution was proposed, which would prohibit manufacturing or possession on absinthe in Switzerland. The article was added following a referendum, in which it won by 241,078 to 139,699 votes, and would be effective October 7, 1910. Eventually, similar incidents led to bans on absinthe in every European country (except the United Kingdom and Spain) as well as the United States.

Wikipedia.org

What were the Lanfray murders?

Oxigenee.com

Maurice Zolotow, in a 1971 article, takes up the story:

"On August 28 1905, Jean Lanfray, a vineyard worker and day laborer in the little village of Commugny, Switzerland, awoke at 4.30 in the morning. He began his day with his usual eye opener: a shot of absinthe, to which he added three parts of water. Before the day was over, Lanfray would commit a series of horrible murders and, ultimately, he would bring about the downfall of a $100,000,000 industry. Lanfray was a tough, burly peasant. He weighed 180 pounds. He was almost six feet tall and was in robust health. He was a Frenchman by birth.

He had served his three years of military service with the Chasseurs Alpins regiment of the French Army. There he had learned two things: how to kill and how to drink absinthe.

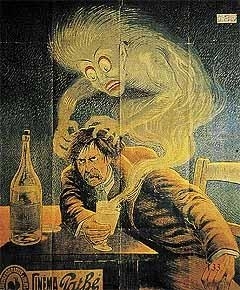

At that time, absinthe was the best-selling before-dinner drink in much of the civilized world. It was - and is - an anise-flavored liquor of high alcoholic strength, preferably 136 proof. It is made by steeping various herbs in neutral grape spirits for eight days and then redistilling the concoction. Among the 15 herbs in absinthe are the dried flowers and leaves of wormwood, a plant that grows about three feet high and is botanically related to our South-Western sagebrush. The German word for wormwood is Wermut, or vermouth; there are small amounts of wormwood oil in vermouth. The Latin for wormwood is Artemisia absinthium, and its oil is known as absinthol, hence the name of this elixir. For many years, a considerable number of French physicians and biologists had regarded the wormwood plant as deadly poisonous.

On what was to be a most eventful day in the history of drinking, Lanfray, 31, got dressed . He lived with his wife and two children on the second floor of a farmhouse. His parents and his brother, Paul, lived downstairs. Lanfray had a second absinthe and water. He wiped his lips. He told his wife to wax his boots while he went about his chores, as he planned to go mushroom hunting in the woods the next morning. His wife grumbled something or other. During the past year, the couple had been constantly quarreling - about money, about her in-laws, about his drinking habits.

"Don't forget to wax my boots," Lanfray repeated. "And make it good, you hear?"

He went to the barn and watered the cows and let them out into the pasture. He returned and had some coffee and bread. The children - Rose, four and a half, and Blanche, one and a half - were still asleep. Lanfray went downstairs. He joined his father and brother. The three Lanfrays then began walking to the vineyards near the village where they were employed. En route, they passed the local auberge and Jean, a man who could not go very long without slaking his awesome thirst, went in.

It was about 5:30 A.M. (a Swiss law- enforcement official, as we shall see, compiled a meticulous record of Lanfrey's alcoholic intake that fatal day) and our man had, first, a creme de menthe with water, and then a cognac and soda. He worked until noon. He had brought bread, cheese and sausage for lunch. With the food, he downed two or three glasses of chambertin . (This was not the famous Burgundian chambertin so prized by wine experts but a local homemade wine made from the district's pinot noir grapes and known in the patois as piquette.) Jean Lanfray's piquette was celebrated for being the strongest in the area. Lanfray could have paraphrased Will Rogers' famous remark about men and said that he had never met a drink he didn't like.

At three P.M., he took a wine break - two more glasses of his piquette. At 4:15, he accepted another glass of red wine offered by a neighbor. At 4:30, the day's work over, Lanfray, his father and his brother dropped into a cafe and he had a cup of black coffee laced with brandy. Later, when the police and psychiatrists delved into his behavior pattern, they found that he drank every day two to two and a half liters of vin ordinaire and two to two and a half liters of the stronger piquette - about six quarts in all. Besides this, he consumed several brandies and cordials plus one or two absinthes a day.

It was then about five P.M. Jean Lanfray and his father went home. There, they each polished off a liter of piquette. Jean's wife was in a bad mood. Besides having two small children to look after, she had to clean the house, cook the meals and help out with the farm chores.

She asked her husband to milk the cows. They had a herd of 20 and sold the milk to a local creamery. Lanfray, having put in a hard day of drinking and digging, was not up to milking cows. He ordered his wife to go to hell and milk the cows herself. Then he demanded hot coffee. She put the coffeepot on the stove. She did not say anything.

In those days, women who knew what was good for them didn't get sassy with their husbands. Lanfray laced the coffee with a healthy slug of marc, a powerful brandy he made himself. His wife went outside. Sometime later, she returned and said she was going to take the milk to the creamery. Her husband complained that the coffee had not been hot enough. She shrugged. Suddenly, he noticed his boots under the sink - unwaxed. He gave her a further piece of his mind. His father started to leave, not wanting any part of this family quarrel. He said goodbye to his daughter-in-law. She shrugged insolently.

Lanfray fils shouted that she should behave more politely to the old man. She shrugged again. He was enraged. He began yelling. And then she yelled back.

"Shut up!" he barked.

She lost her temper: "I'd like to see you make me!"

You would, would you?" he snarled. He went and got his old Vetterli rifle, a long-barreled (33.2 inches), bolt-action repeater that took a magazine of 12 cartridges.

"Don't do anything foolish," the old man pleaded.

"You stay out of this, Poppa, unless you want trouble yourself!"

Lanfray raised his Vetterli, took aim and shot his wife in the head. She fell and died almost instantly. The old man ran out, shouting, "Au secours, secours!" The oldest daughter ran into the room. She screamed. Jean shot her in the chest. She fell, mortally wounded. Next, he went to the cradle where little Blanche was sleeping. He killed the infant.

Then he set out to take his own life. He held out the rifle and tried to aim it at his head, but it was too long. He got a string and tied it to the trigger, passed it behind the trigger bar, then held the free end of the string with one hand and the rifle by the barrel with the other hand. He was thus able to draw a bead on his own head, but he missed his brain; the bullet lodged in his lower jaw. Bleeding profusely, Lanfray tucked the corpse of his youngest girl under his arm. He went into the barn. He lay down on the ground and fell into a deep sleep, where the police found him and took him into custody. He was "dazed and incoherent," according to their account.

He was taken first to the hospital in nearby Nyon, where the bullet was removed from his jaw. He fell asleep again at once. Later, he was taken to see his three victims in their coffins. Nurse Marie Blaser said that the murderer wept and moaned over and over, "It is not me who did this. Tell me, O God, please tell me that I have not done this. I loved my wife and children so much." Lanfray insisted he did not remember anything about the murders.

On September 3, 1905, a Sunday, the citizens of Commugny held a mass meeting in the schoolhouse. The villagers, horrified by the crime, learned after an autopsy on Mme. Lanfray that she was four months pregnant with a male fetus. The community had to find a scapegoat. Absinthe became that scapegoat.